Abstract

Genomic instability is a defining characteristic of cancer and the analysis of DNA damage at the chromosome level is a crucial part of the study of carcinogenesis and genotoxicity. Chromosomal instability (CIN), the most common level of genomic instability in cancers, is defined as the rate of loss or gain of chromosomes through successive divisions. As such, DNA in cancer cells is highly unstable. However, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. There is a debate as to whether instability succeeds transformation, or if it is a by-product of cancer, and therefore, studying potential molecular and cellular contributors of genomic instability is of high importance. Recent work has suggested an important role for ectopic expression of meiosis genes in driving genomic instability via a process called meiomitosis. Improving understanding of these mechanisms can contribute to the development of targeted therapies that exploit DNA damage and repair mechanisms. Here, we discuss a workflow of novel and established techniques used to assess chromosomal instability as well as the nature of genomic instability such as double strand breaks, micronuclei, and chromatin bridges. For each technique, we discuss their advantages and limitations in a lab setting. Lastly, we provide detailed protocols for the discussed techniques.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12079-021-00661-z.

Keywords: Genomic instability, Chromosomal instability, DNA damage, H2B-GFP, Cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay, Single-cell sequencing, Meiomitosis

Introduction

Genomic instability is a fundamental defining characteristic of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011) that is essential for disease initiation and progression. Such instability can be subcategorized into three types: nucleotide instability (NIN) comprised of DNA sequence variations characterized by base substitutions, deletions and insertions of one or a few nucleotides; microsatellite instability (MIN or MSI) composed of short nucleotide repeat sequences resulting from impaired DNA mismatch repair; and chromosomal instability (CIN) constituted of structural and numeric irregularities at the chromosomal level (Lengauer et al. 1998).

CIN, characterized by ongoing errors in chromosomal segregation throughout successive cell divisions, provides a proliferative advantage to cancer cells and is therefore particularly important in cancer progression (Lengauer et al. 1998). Research shows that in 60% to 80% of human malignant tumors demonstrate CIN (Carter et al. 2012; Cimini 2008) making it the most common form of genomic instability. Errors in chromosome segregation result in numerous cellular aberrations, including a loss of DNA (Santaguida et al. 2017; Sheltzer et al. 2017; Torres et al. 2007) resulting in daughter cell aneuploidy; the activation of DNA damage signaling pathways leading to cellular senescence; and suboptimal DNA repair promoting additional genomic instability (d'Adda di Fagagna et al. 2003; Freund et al. 2010; Kang et al. 2015).

The expression of cancer/testis antigen (CTA) genes may promote genomic instability in cancers (Greve et al. 2015; Tsang et al. 2018). A specific subtype of CTAs known as meiosis-specific CTAs (meiCT) are genes restricted to the ovaries, testes, and placenta but can be ectopically expressed in cancer (Feichtinger et al. 2012; Gantchev et al. 2020). Two meiCT genes, HORMAD1 and SYCP3 have been shown to be strongly expressed in highly genomically unstable cancers with poor prognoses (Adelaide et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2019; Chung et al. 2013; Kitano et al. 2017), suggesting a role in DNA damage/repair processes.

In this work, we highlight methods that can be used to detect and analyze genomic instability in cancers. We have created a detailed workflow to evaluate key features of genomic instability that include DNA damage, micronuclei development, chromatin and anaphase bridge formation, as well as aneuploidy.

Methods of detection and analysis for genomic instability in cancer

DNA breaks

DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) are considered the most lethal of DNA lesions. DSBs can arise from exposure to radiation, chemotherapy and other genotoxic chemicals. If not repaired rapidly and precisely, these lesions can ultimately lead to chromosomal aberrations, mutations and carcinogenesis (Cannan and Pederson 2016). There are a few specific molecules that are classically used to determine the presence of DSBs in higher eukaryotic cells. One of the most commonly used markers and one of the earliest cellular responses triggered by the formation of DSBs in the chromatin is the phosphorylation of H2AX histones at Ser-139 to produce H2AX (Redon et al. 2002). This phosphorylation is a widely recognized chromatin modification linked to DNA damage and repair (Redon et al. 2002; Rogakou et al. 1998, 1999; Sedelnikova et al. 2002). Immunochemical techniques using phosphospecific antibodies that recognize the phosphorylated S-139 residue of γH2AX with immunofluorescence, discrete nuclear foci at the site of DSBs can be observed and monitored (Kuo and Yang 2008; Podhorecka et al. 2010). The formation of γH2AX foci is a widely accepted quantitative marker of DSBs that can be applied to a variety of experimental conditions (Rothkamm and Löbrich 2003).

Another well-known molecule that is phosphorylated and recruited to sites of DNA DSBs is a tumor suppressor p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1). 53BP1 forms nuclear foci in a similar fashion as the γH2AX. In fact, γH2AX is involved in the recruitment of 53BP1 in some tissues (Guo et al. 2018; Kleiner et al. 2015) thus, their presence at DSBs can be related. Research has shown that in retinal tissues, 53BP1 foci were under-expressed when compared to γH2AX foci, suggesting that phosphorylation of H2AX does not always entail recruitment of 53BP1 (Muller et al. 2018). Therefore, one should exercise caution when analyzing 53BP1 staining independently of γH2AX, as negative results do not necessarily indicate the absence of DNA damage (Figs. 1A–B). In most cases, identifying nuclear foci of γH2AX or 53BP1 in a cell is of utmost relevance to identifying genomic instability.

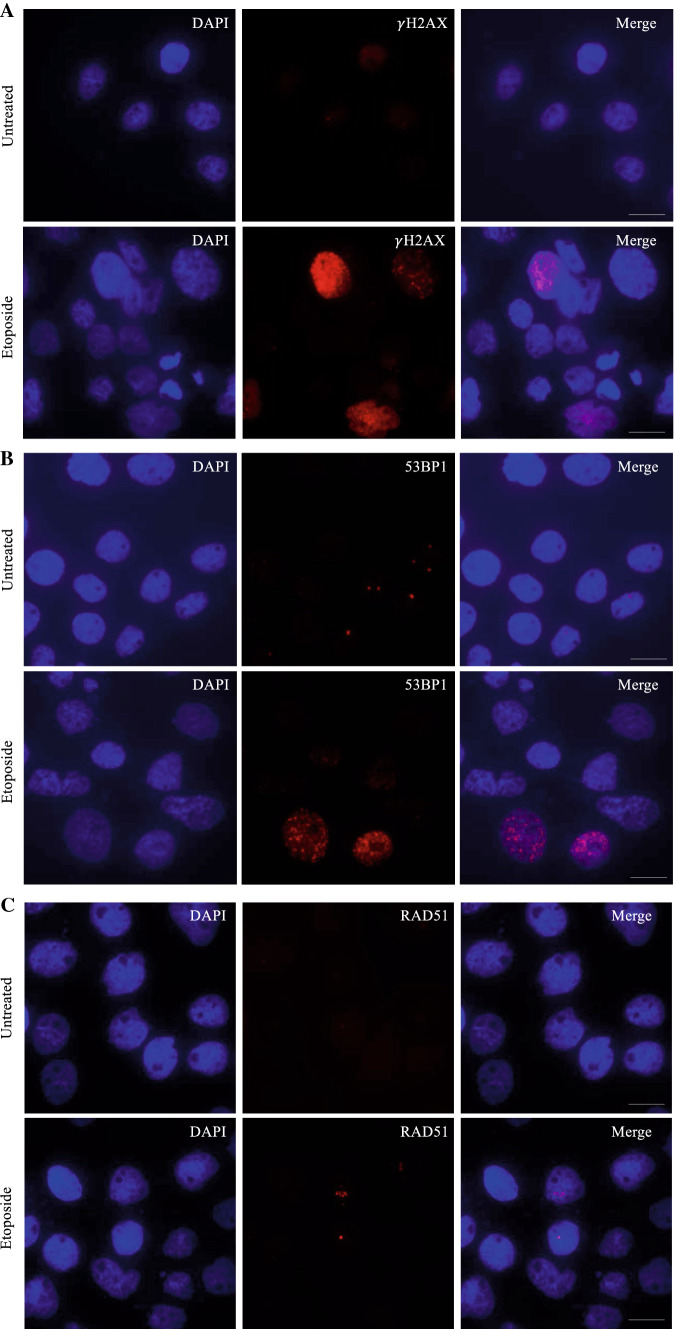

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence staining using indicators of DNA damage in the cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell line, A431. Examples of representative images for untreated and cells treated with 1 m of etoposide are shown for A H2AX; B 53BP1; and C RAD51. Photos taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 60X objective (Meiji MA969). Scale bar 20 m

The radiation sensitive 51 (RAD51) recombinase can also be used to detect DNA double strand breaks. RAD51 plays an essential role in homologous recombination repair (HRR) by mediating pairing and strand exchange reactions between homologous DNA strands at the sites of single and double stranded DNA (Baumann and West 1998; Henning and Stürzbecher 2003; Krejci et al. 2012). Following DNA damage, RAD51 forms nuclear foci similar to that of γH2AX and 53BP1. Although RAD51 is a commonly used assay to analyze ongoing HRR (Gachechiladze et al. 2017), it has also been used to assess DSBs in response to DNA damaging agents such as chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer cell lines, primary cells and stem cells (Serrano et al. 2011; Tahara et al. 2014).

Immunofluorescence microscopy is most often used to identify the nuclear foci formed by γH2AX, 53BP1 or RAD51. There are several advantages to using immunofluorescence to assess genomic instability. First, immunofluorescence can provide both qualitative and quantitative insights. This is especially true for the staining of γH2AX, as the number of nuclear foci and DNA double-strand breaks are related 1:1 (Kuo and Yang 2008). This technique provides further positional information about the foci, as the fluorescent foci reflect the locations of the biological foci with high fidelity. Furthermore, γH2AX staining is at least 100-fold more sensitive than other methods used to identify DSBs. The use of γH2AX as a DSB indicator of radiation doses has been previously validated, where formation of one focus in every 30 cells corresponds to 1 mGy exposure (Baumann and West 1998; Henning and Stürzbecher 2003).

The evaluation of changes of the DSB markers γH2AX, 53BP1 and RAD51 following genetic manipulation or therapeutic intervention can be used to elucidate roles in DNA damage repair or genomic instability. The detailed immunofluorescence staining protocol with suggested validated antibodies is listed in Supplementary Materials. An example of staining for γH2AX, 53BP1 and Rad51 in A431 cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) cells before and after 72 h of treatment with 1.0 m of etoposide is presented in Fig. 1. In this example, it is evident that etoposide treatment leads to a significant upregulation of γH2AX, 53BP1 and RAD51 foci in the cell.

Additionally, the evaluation of specific patterns of staining before and after treatment or following genetic manipulation can provide valuable biologic information beyond simple classification as positive vs. negative result. Indeed, γH2AX and 53BP1 have specific, nuanced staining patterns found in a population of cells following gamma ray irradiation, ultraviolet (UV) exposure or chemotherapy treatments. The types of immunofluorescent staining observed can be correlated with the level of DNA damage in a cell. With respect to γH2AX, three types of immunofluorescence staining patterns have been classified: type 1- low level of DNA damage/DNA DSBs with less than 10 γH2AX nuclear foci; type 2- high level of DNA damage with more than 10 foci reflecting; and lastly type 3- pan-nuclear staining representing a pre-apoptotic phenotype (Ding et al. 2016; Halicka et al. 2005; Lu et al. 2017; Marti et al. 2006; Solier and Pommier 2009) (Fig. 2A). Similarly, some studies use a classification system of immunofluorescent staining patterns for 53BP1. Matsuda and colleagues used the cervical cell line, HeLa, to classify immunoreactivity of 53BP1 staining into four types: type 1- faint and diffuse nuclear staining representing stable/routine conditions; type 2- low DNA damage response (Aaij et al. 2018) with one or two discrete nuclear foci; type 3-high DDR with three or more discrete nuclear foci representing high DNA damage; and type 4- large (1.0 m) nuclear foci indicative of abnormal and heterogenous 53BP1 expression (Fig. 2B). Fluctuations in the amount of DNA damage can be evaluated using this system and can, therefore, provide detailed information on the quantity of damage cells can withstand or the level of DNA damage a particular intervention can produce.

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence staining patterns are indicative of levels of DNA damage in A431 cells. A Three types of H2AX staining patterns corresponding to the number of double strand DNA breaks are as follows: type 1 expression of less than 10 nuclear foci indicates low levels of DNA damage/DNA DSBs; type 2 expression of greater than 10 nuclear foci indicate a high level of DNA damage/DNA DSBs and type 3 pan-nuclear expression indicates pre-apoptotic state. B Four distinct types of 53BP1 expression patterns are as follows: type 1 stable expression of faint diffuse nuclear staining; type 2 expression of one or two discrete nuclear foci indicates low DNA damage response; type 3 expression of three or more discrete nuclear foci indicates high DDR; and type 4 expression of nuclear foci greater than 1.0 M indicates abnormal/uncharacteristic expression for this protein. Photos taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 60X objective (Meiji MA969). Scale bar 10 m

Centrosomes

Centrosomes are vital in coordinating the assembly and function of the mitotic spindle, to regulate the precise separation of homologous chromosomes into daughter cells. The dysfunction of centrosomes is intimately linked to chromosomal instability and aneuploidy (Mikule et al. 2007). Centrosomes are composed of centrioles and the surrounding pericentriolar material (PCM) (Azimzadeh and Bornens 2007; Bornens 2012; Bornens and Gonczy 2014). Pericentrin is a proteinaceous component of the PCM that contributes to a plethora of fundamental cellular processes by interacting with numerous proteins and protein complexes. Specifically, pericentrin has been shown to be involved in the progression from G1 to S and from G2 to M (Doxsey et al. 2005; Kramer et al. 2004), mitotic spindle organization (Luders and Stearns 2007; O'Connell and Khodjakov 2007) and mitotic spindle orientation (Rebollo et al. 2007; Rusan and Peifer 2007; Toyoshima and Nishida 2007). Most importantly, pericentrin ensures uninterrupted cell cycle progression. Pericentrin is a bona fide marker for centrosomes (Doxsey et al. 1994) and is commonly used to evaluate defects in cancer. Increased pericentrin levels and defects in pericentrin organization accompany abnormalities in solid malignancies such as breast, cervical, ovarian/testicular, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas amongst others (Wu et al. 2020) (reviewed in (Chan 2011) and (Godinho and Pellman 2014)). Studies in breast cancer have demonstrated that centrosomal aberration and amplification correlate with higher tumor grade (Kang et al. 2015; Sheltzer et al. 2017; Torres et al. 2007) and metastatic potential (Cannan and Pederson 2016; d'Adda di Fagagna et al. 2003; Freund et al. 2010). Centrosome amplification correlates strongly with poorly differentiated breast cancer tumors and was shown to induce cellular de-differentiation (Denu et al. 2016). Furthermore, pericentrin overexpression in human cultured prostate cells reproduces characteristics of aggressive prostate cancer that includes abnormal spindle formation, centrosome defects and CIN (Delaval and Doxsey 2010). Similarly, in hematologic malignancies, high levels of pericentrin expression, indicating centrosome amplification, correlate with aneuploidy and centrosome aberration in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) (Giehl et al. 2005; Kramer et al. 2005; Neben et al. 2004; Patel and Gordon 2009). Disrupted/amorphous pericentrin staining has been consistently documented in advanced stage Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) (Giehl et al. 2005; Kramer et al. 2005; Neben et al. 2004; Patel and Gordon 2009).

Studies by Pihan and colleagues have proposed a model to explain how disturbances in pericentrin function can induce tumor formation (Pihan and Doxsey 2003; Pihan et al. 2001). The model proposes that increased levels of pericentrin leads to alterations in centrosome number, structure (shape and size) and function. These alterations change mitotic spindle organization and function, thereby, leading to chromosome missegregation (Delaval and Doxsey 2010). The resulting aberrations become increasingly prevalent in malignant cells with each division and ultimately lead to cancer progression by promoting genomic instability (Pihan et al. 1998). Alternative mechanisms leading to centrosome/pericentrin amplification include cytokinesis failure, cell–cell fusion, endoduplication, centrosome duplication and PCM fragmentation (Chan 2011; Godinho and Pellman 2014).

A detailed protocol for pericentrin immunofluorescence and analysis is presented in Supplementary Materials. Immunofluorescence staining of pericentrin allows to detect the intensity levels of pericentrin staining and abnormal centrosome number in mitotic cells. In particular, occurrence of supernumerary pericentrin foci in metaphase correlates with the frequency of lagging chromosomes and subsequent ensuing genomic instability (Ganem et al. 2009). High number of centrosomes correlates with more aggressive malignant phenotype, fused cells, aneuploid cells, aberrant anaphase/cytokinesis and a high likelihood of detecting lagging chromosomes. Furthermore, supernumerary centrosomes correlate with micronuclei formation in cancer cells. Figure 3A demonstrates a normal metaphase plate formation along with aberrant metaphase cells exhibiting aberrant numbers of centrosomes, as indicated by pericentrin staining. Figure 3B demonstrates pericentrin overexpression in A431 cells treated with etoposide.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence staining of human A431 cells with pericentrin antibody. A Normal metaphase A431 cell with two pericentrin foci indicative of two centrosomes at opposing poles of the cells compared to B–C abnormal number of pericentrin foci indicative of more than two centrosomes in a single dividing cell at metaphase. Arrows point to metaphase cells. D–E Pericentrin expression in interphase cells. (1) Demonstrates an interphase cell with normal level of pericentrin expression, magnified in F. (2) Demonstrates pericentrin overexpression, magnified in G. Photos taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 60X objective (Meiji MA969). Scale bar 20 m

Chromosomal instability (CIN)

CIN is the rate of acquisition of chromosomal abnormalities that is further classified into a structural or numerical state of CIN (Schukken and Foijer 2018). Structural CIN is characterized by gains, losses or translocations of segments of chromosomes. Whereas numerical CIN, also known as aneuploidy, is characterized by a gain or loss of whole chromosomes that leads to a change in a cell karyotype (Tanaka and Hirota 2016). Defects underlying CIN include lagging chromosomes (Ricke et al. 2008), micronuclei (He et al. 2019), chromatin bridges (Passerini et al. 2016), chromosome missegregation, cytokinesis failure (Fujiwara et al. 2005; Nicholson et al. 2015), telomere dysfunction (Gisselsson et al. 2001) and spindle failure (Maiato and Logarinho 2014; Vitre et al. 2015). Approaches to evaluate aneuploidy and examine defects underlying CIN remain critical in the study of cancer biology.

Cytokinesis block micronucleus (CBMN) assay

The micronucleus is an important abnormal cellular structure that evolves in CIN-positive cancer cells (Leung et al.) Micronuclei are biomarkers of broken chromosomal fragments formed due to DNA damage. Alternatively, they form by enclosing whole chromosomes due to a phenomenon referred to as a lagging chromosome. Additionally, DSBs, defective cell cycle control, and mitotic spindle failure can lead to aberrant chromosome segregation and micronucleus formation. Micronuclei have been recognized as markers of carcinogenesis in liver (Livezey et al. 2002), colorectal (Bonassi et al. 2011), retinoblastoma (Amato et al. 2009) and cervical cancers (Gayathri et al. 2012).

The CBMN assay is a technique used to measure DNA damage, necrosis, apoptosis, cytostasis and cytotoxicity (Fenech 2007; Thomas et al. 2003). Specifically, the CBMN assay measures micronuclei formation, chromosomal breakage and loss, chromatin bridges (i.e., nucleoplasmic/anaphase bridges), nuclear bud formation in binucleated cells and is acknowledged as a preferred technique in studying genotoxicity (Thomas et al. 2003). Originally developed to analyze lymphocytes (52), the CBMN assay is also used to score MN in epithelial cells (El-Zein et al. 2018) and in mesenchymal stem cells (Cornélio et al. 2014).

Cytokinesis block is achieved by using the mycotoxin, cytochalasin-B (cyt-B) (Fenech and Morley 1985). Specifically, cyt-B inhibits actin polymerisation required for the microfilament ring formation and therefore, prevents division of the cytoplasm between daughter cells following a nuclear division (Carter 1967; Fenech and Morley 1986). Inhibition of dividing cells with cyt-B at the binucleated stage allows for a prolonged time to enable resolution of chromatin bridges that would otherwise be crushed due to mechanical shearing forces in cytokinesis. Additionally, inhibition of cytokinesis should avert breaking chromatin bridges allowing for their accumulation in binucleated cells for subsequent analysis (Thomas et al. 2003).

Following the treatment with cyt-B, a nucleic-acid selective fluorescent agent such as acridine orange or DAPI (4’,6- Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride), can be used to visualize the DNA in a population of binucleated cells (Fenech 2000). Micronuclei, chromatin bridges and nuclear buds are scored in binucleated cells and can be used as reliable comparisons of chromosomal instability between cell populations (Fenech 2000). The CBMN assay can be carried out in a dividing population of cancer cells in the presence or absence of a genotoxic agent. Restricting scoring of micronuclei to binucleated cells prevents confounding effects due to cell division kinetics, a prominent variable in micronuclear analysis protocols that do not take into consideration that non-dividing cells are not able generate these structures (Fenech, 2007). In the CBMN assay, cytostatic effects are calculated by recording the proportion of mono-, bi-, and multinucleated cells as well as necrotic and apoptotic cell ratios (Fenech 2007). Additional optional steps can include using cell sorting techniques to increase the yield of binucleated cells for subsequent analysis (Nakamura et al. 2016).

To identify mechanisms involved in micronucleus induction, a combination of the CBMN method with immunochemical labeling of kinetochores (Eastmond and Tucker 1989) or centrosomes with pericentrin or in situ hybridization with centromeric/telomeric probes (Eastmond et al. 1994; Norppa et al. 1993) can be used. This combination of techniques can identify DSBs with acentric fragments and failure of mitotic components throughout the cell cycle that results in a formation of micronuclei enclosing whole chromosomes (Kirsch-Volders et al. 2003).

The creator of the CBMN technique, Dr. W. Fenech, developed a binucleate cell index (BCI) that measures cytotoxicity by classifying the number of nuclei in cells (Fenech 1993). A group of researchers created a cytokinesis-block proliferation index (CBPI) to provide information of cell cycle kinetics (Kirsch-Volders et al. 2003). Together, these two indexes provide a reliable framework to assess components of genomic instability. The CBMN method of detecting micronuclei gained a significant attention and was the basis of a collaborative project launched in 1997, that involved 34 laboratories in 21 countries. The International Collaborative Project on MN Frequency in Human Population (Bonassi et al. 2003) relied heavily on the CBMN to establish a standard protocol in evaluating micronuclei in order to recognize them as a valuable biomarker in cancer (Fenech et al. 1999).

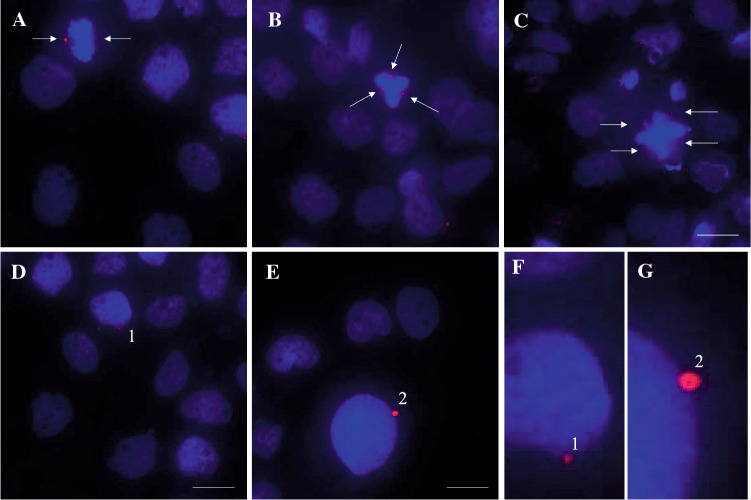

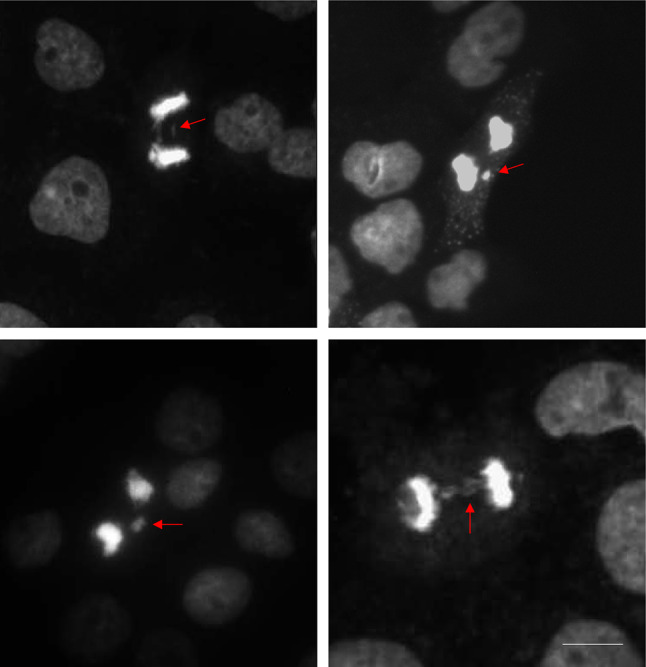

A detailed protocol for CBMN assay is presented in Supplementary Materials. Figure 4 shows CAL27, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells dividing in the presence of 5 Gy irradiation. Arrows highlight the presence of micronuclei and nuclear buds.

Fig. 4.

Cytokinesis block micronucleus (CBMN) assay. A Mononucleated cell; B binuclear cell; C multinucleated cell; D binuclear cells with micronuclei (arrow); E nuclear bud (arrow); F late apoptotic cell. Photos taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 60X objective (Meiji MA969). Scale bar 10 m

Although the CBMN assay is a highly sensitive test that provides important information on asymmetrical chromosomal rearrangement, chromosomal breakage/loss and gene amplification, it does have critical caveats. For instance, it is possible that some micronuclei may become visually obstructed by the main nucleus in the slide preparation, some nuclear fragments can integrate into the nuclei during anaphase due to spatial proximity to the rest of the chromosomes. Additionally, high radiation doses can fuse two or more chromosome fragments into one larger micronucleus and, therefore, make it appear to be of relatively normal size (Thomas et al. 2003).

Lagging chromosomes and cell cycle synchronization

Lagging chromosomes represent a form of chromosome missegregation, are frequently observed in unstable cancer cells with high levels of CIN and are most commonly a result of a merotelic attachment. A merotelic attachment occurs when a single kinetochore on a chromosome attaches to microtubules emanating from two spindle poles. Merotelic attachments have been proposed to be a significant contributor to the spontaneous formation of lagging chromosomes that form in the space between two segregating masses of chromosomes in anaphase. Although, most lagging chromosomes are resolved by the start of cytokinesis, studies have demonstrated that lagging chromosomes not properly integrated in the nucleus often form micronuclei (Kang et al. 2015; Thompson and Compton 2011). In fact, most lagging chromosomes are not contributors to aneuploidy but create micronuclei in its corresponding daughter cell (Huang et al. 2012). The DNA contained in the micronucleus is likely to be whole chromosomes and thus experience unusually high levels of DNA damage (Zhang et al. 2015).

Lagging chromosomes are distinctly vulnerable to DNA damage in various ways. The nuclear envelope surrounding micronuclei is remarkably fragile and can be easily disrupted, thereby, exposing its DNA to cytoplasmic constituents (Hatch et al. 2013). Furthermore, if the nuclear envelope is affected during the S phase, stalled replication and DNA damage ensues (Crasta et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2015). Lastly, DNA replication kinetics of the micronuclei are often delayed (Crasta et al. 2012). Therefore, replication of micronuclear DNA continues into cellular cytokinesis stage, which can lead to premature condensation and fragmentation of the DNA contained in the micronucleus (Crasta et al. 2012; Ly et al. 2017). Fragmentation promotes random nuclear integration leading to chromosomal rearrangements in succeeding daughter cells thereby, increasing DNA damage levels in the cell (reviewed in (Holland and Cleveland 2012)).

The analysis of lagging chromosomes can be performed through live cell imaging using Histone 2B-Green Fluorescent Protein (H2B-GFP) staining (described in detail in Sect. 3D in Supplementary Materials) or in fixed cell populations using DAPI to visualize chromosomes in anaphase. Visualizing anaphase is difficult since this is a brief phase (a rare event in a population of exponentially growing cells) and represents a time-consuming task. Hence, to attain a sufficient number of cells, our lab utilizes a series of simple experiments presented below, to maximize the number of anaphase cells in a given population, which helps increase the sample size and power for statistical analysis.

To study lagging chromosomes during anaphase, cell synchronization can be harnessed to maximize the number of cells in a specified phase of the cell cycle (Banfalvi 2017). Specifically, cell synchronization is a process by which cells in culture are artificially brought to the same phase.

Various physical and chemical methods are available to implement cell synchronization (Banfalvi 2016). When selecting a method, it is important to choose the protocol best adapted to the objective of a given study, ensuring the absence of interaction between the effect of the synchronizing agent and the investigated process (Uzbekov 2004). There are two principal strategies used in most synchronization protocols: physical fractionation and a chemical blockade (Banfalvi 2016). In physical fractionation, cells are separated based on cell density, size, antibody binding to cell surface epitopes, fluorescent emission of labeled cells and light scatter analysis (Banfalvi 2016). The advantage to physical methods is evading the use of pharmacologic drugs that are more likely to inadvertently change characteristics of the cells. However, a major limitation is the requirement of specially designated, and often expensive equipment (Merrill 1998). Furthermore, the process of isolating cells using antibodies, cell sorting or other aforementioned parameters may still impact the biology of the cell. In chemical synchronization, cells are exposed to an agent that interferes with the cell cycle progression thereby arresting them in that given stage (Banfalvi 2016). The cells are said to be ‘blocked’ at the selected phase, but can be released with the addition of buffer agents or by washing off the offending agent using media. The subsequent addition of exogenous substrates, such as nucleosides and nucleotides, allows the cell to progress through the remaining phases of its cycle reproducing the wavelike nature of the cell cycle in vitro (Banfalvi 2016).

While the physical methods of cell synchronization have been extensively reviewed in (Banfalvi 2011), we will focus on two chemical strategies to synchronize cancer cells that maximizes the number of anaphase cells observed in a single immunofluorescent preparation: thymidine block and hydroxyurea block with isoleucine-free media.

Cellular metabolic processes are often blocked by the inhibition of DNA replication and by nutritional deprivation that inhibits DNA polymerization. Excess thymidine or hydroxyurea are often used to inhibit DNA synthesis in the S-phase of the cell cycle (Banfalvi 2016). Both methods require two incubation periods in the presence of the blocking agent to induce phase synchrony of the cells (Merrill 1998). The use of excess thymidine as a synchronizing agent in the double-thymidine block procedure illustrates this point. The high concentration of thymidine interferers with the deoxynucleotide metabolic pathway thereby halting DNA replication in the S-phase (Uzbekov 2004). This first treatment with thymidine arrests cells throughout the S-phase of the cell cycle resulting in imperfectly synchronized cells. Thus to overcome this limitation and to achieve an efficient early S-phase synchronization of cells, a second thymidine block treatment is performed (Uzbekov 2004). After the initial release (lasting 9 h by adding complete medium) from the first thymidine block cells progress synchronously through G2 and mitotic phases producing a large yield of cells subsequently arrested at the beginning of S-phase by the second thymidine block treatment (Chen and Deng 2018). Following release from the second thymidine block by the removal of thymidine and the addition of fresh media, > 95% of HeLa cells then progress into G2 phase within 5–6 h, enter mitosis at 7–8 h time point and re-enter S-phase upon completion of one cell cycle at 14–16 h (Whitfield 2002). It is important to note, when conducting this experiment, observing cells under the microscope every few hours is necessary to determine the specific time frame required for fixation in the phase desired for your study. If a time course of mRNA/protein expression by RT-PCR or a western blot is the objective of the study, visual optimization may not be necessary.

The second method, isoleucine deprivation, was first established in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells by Tobey et al. in the 1970’s but is now applied to several cell lines, albeit with varying rates of success (Fantes and Brooks 1993; Tobey 1972). Tobey and Ley demonstrated that starvation of CHO cells in an F10- isoleucine-free culture-medium results in a reversible arrest of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Tobey 1972). Isoleucine is a precursor for glutamine and alanine and thus, has a key role in the cellular energy generation. Depriving cells of this essential amino acid leads to an arrest of DNA-synthesis and thus synchronization of cells at G1 (D'Anna 1996). Cells can be released from G1 phase by the addition of L-Isoleucine back into the medium (Tobey 1972). The technique yields suitable quantity of cells for the study of cellular events associated with the initiation of genome replication and completion of interphase and works equally well for both monolayer and suspension cultures (D'Anna 1996). We present in Supplementary Materials a detailed protocol for cell synchronization using the double thymidine block method and subsequent analysis of lagging chromosomes. Figure 5 demonstrates the presence of lagging chromosomes visualized during anaphase in the thymidine synchronized cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell line, A431.

Fig. 5.

Double thymidine block synchronized A431 cells at anaphase showing events of lagging chromosomes (arrows). Cells were stained with DAPI and viewed under a fluorescence microscope. Photos taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 40X objective (Olympus LUCPLFLN40X). Scale bar 10 m

If cell synchronization alone is not sufficient to capture the required number of anaphase cells, a classical anaphase block technique can be utilized. Traditionally, three chemical methods can be used to block cell lines in anaphase: blebbistatin, dinitrophenol with azide, and carbonyl cyanide chlorophenyl hydrazine. First, blebbistatin is a myosin II inhibitor presumed to extend the duration of anaphase via its effect on the cleavage furrow ingression in the later stages of mitosis (Straight et al. 2003). Furrow ingression relies on non-muscle myosin II ATPase, and therefore, blocking its function with blebbistatin leads to cytokinesis failure (Straight et al. 2003). A recent study reported an enrichment of cells in anaphase by sequentially treating the asynchronous culture with 4 mM thymidine and 20 ng/ml nocodazole. The nocodazole-arrested cells were then released for 20 min and subsequently treated with 50 mM of blebbistatin, successfully producing an anaphase-enriched cell culture (Matsui et al. 2012).

Second, dinitrophenol (DNP) and azide are ATP synthesis inhibitors that have been shown to reversibly block anaphase at any point, with chromosome motion ceasing after 1–10 min (Hepler and Palevitz 1986). Additionally, prometaphase, metaphase, and cytoplasmic streaming are also arrested (Hepler and Palevitz 1986). Interestingly, motion can be stopped and restarted several times in the same cell. Lastly, carbonyl cyanide chlorophenyl hydrazone (CPPP) at concentrations of 5 × 10–6 or 10–5 M in 1% ethanol has also been examined and found to stop anaphase chromosome motion and protoplasmic streaming within 3–7 min, but unlike DNP and azide, its effects are not reversible (Hepler and Palevitz 1986). Although these methods can be used, it has been notoriously difficult for researchers to synchronize cells in anaphase because of the relatively short duration of this stage of the cell cycle (Banfalvi 2016; Matsui et al. 2012). In addition, no drugs have been discovered that can block cells with efficient and consistent levels in these later stages of mitosis (Banfalvi 2016; Wee and Wang 2017).

Chromatin bridges

Apart from lagging chromosomes, chromosome missegregation can be also be attained by the fusion of anaphase chromosomes to form a chromatin bridge. A chromatin bridge is a string of chromatin connecting two bodies of DNA between cleaved daughter nuclei representing nucleoplasmic/anaphase bridges. Chromatin bridges are typically formed due to the failure to remove recombination or replication intermediates during or soon after S-phase (Chan and Hickson 2009; Chan et al. 2007; Germann et al. 2014). Chromatin bridges contribute to genomic instability in cancer cells if left unresolved before cytokinesis (Hoffelder et al. 2004). The mechanism driving chromatin bridges is the widely accepted breakage/fusion/bridge cycle model (Fig. 6). This model proposes that fused anaphase chromosomes break during telophase to create chromosome ends that will then fuse with other broken ends during the next cell cycle (McClintock 1939, 1941). After multiple cycles of breakage and fusion through successive cellular divisions, extensive rearrangements of the genome can occur that can lead to gene amplification (Hoffelder et al. 2004) aneuploidy (Pampalona et al. 2010; Stewenius et al. 2005) and polyploidy (Pampalona et al. 2012; Romanov et al. 2001). At the molecular level, chromatin bridges result from defects in telomere structure or length, defects in DNA replication, abnormal recombination or increased number of translocations in a bivalent chromosome, a pair of sister chromatids in a tetrad (Hoffelder et al. 2004).

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) cycle. The BFB cycle is initiated when a double strand break occurs in an unreplicated chromosome leading to the loss of its telomere. 1 Following replication, both sister chromatids are telomere deficient. 2 The unprotected chromosomal ends of the sister chromatids fuse with one another, forming a dicentric chromosome. 3 The fused chromatids form a bridge during anaphase, where the two centromeres are pulled to opposing sides of the cell. 4 The bridge breaks at a random position, usually in a different site than the original fusion resulting in an inverted duplication in one of the daughter cells. The other daughter cell inherits a terminal deletion. Both chromosomes can then lead to more BFB cycles until the end acquires a telomere. Subsequent BFB cycles result in amplification of DNA sequences located near the telomere end and the progressive accumulation of terminal deletions. Adapted from Bailey and Murnane (Bailey and Murnane 2006)

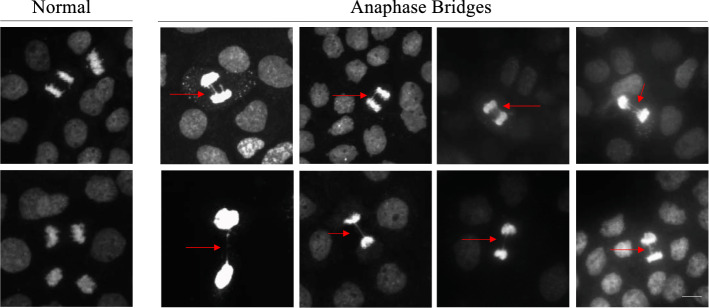

The visualization of chromatin bridges requires a DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) stain and a fluorescence microscope. Figure 7 demonstrates presence of chromatin bridges in the thymidine synchronized A431 cell line. Typically, a chromatin bridge scoring tool is used to assess genomic instability as a dose-dependent marker of tumorigenesis since cancerous DNA is unstable and the likelihood of these events is increased, when compared to normal cells. Nonetheless, bridge formation does not occur frequently, even in cancer cells (Hoffelder et al. 2004) and can be tedious and time consuming to attain.

Fig. 7.

Anaphase bridge formation in A431 cells synchronized with the double thymidine block method. Examples of DAPI-stained anaphase cells with chromatin bridge formation compared to normal anaphase cells, as indicated in the above images. Photos taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 40X objective (Olympus LUCPLFLN40X). Scale bar 20 m

Live cell cycle imaging

Live-cell fluorescence microscopy is a prevailing method to investigate the dynamics of cellular function in real time. This technique possesses high-resolution analysis of cell cycle progression that permits the identification of aberrations in chromosomal separation in anaphase. One common method for live imaging of the cell cycle uses histone 2B-Green Fluorescent Protein (H2B-GFP) fusion constructs to generate fluorescent chromatin. Transfecting cells with this construct permits high-resolution live imaging of the cell cycle, using confocal microscopy (Kanda et al. 1998). The H2B-GFP fusion protein provides stability and nuclear localization suitable for cell cycle analysis. Research has shown that both normal, double minute chromosomes (DMC), round-circle, acentric double-strand extra-chromosome DNA (Benner et al. 1991; Boone and Kelloff 1994; Montagna et al. 2002; Morales et al. 2005; Papachristou et al. 2008; Seruca et al. 1995; Zimonjic et al. 2001) and chromatin bridges are easily identified using fluorescence.

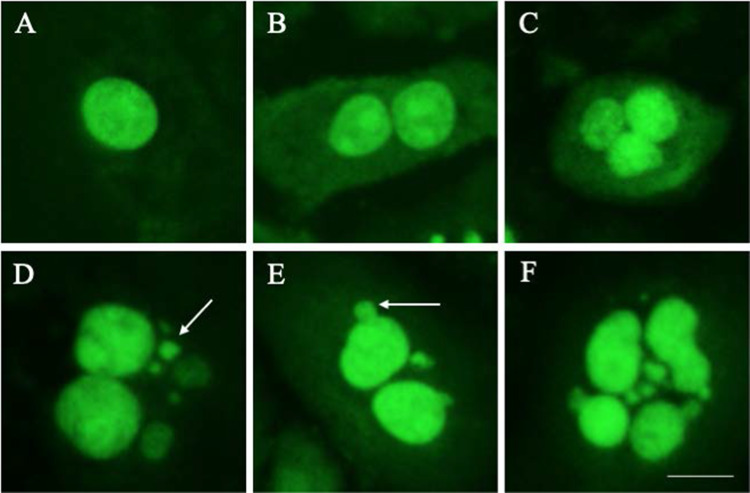

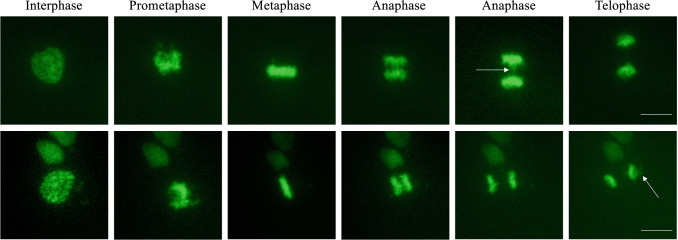

The H2B-GFP method is widely used for its high resolution, simplicity and stable fluorescence (Chen et al. 2016; Kanda et al. 1998). If imaging is conducted without perturbing cell physiology, then live imaging may also provide relevant structural and dynamic insights (Cole 2014). A key advantage of using H2B-GFP and live cell imaging to detect chromatin bridges is the ability to observe chromosomes in their native state over a long period of time without disturbing the cell cycle and without fixation or permeabilization techniques that can distort intracellular structures (Cole 2014; Kanda et al. 1998). H2B-GFP permits monitoring chromosomal location, movement and condensation states throughout the stages of mitosis allowing the visualization of aberrations in real time. A detailed protocol for this method is presented in Supplementary Materials. Figure 8 demonstrates H2B-GFP imaging in A431 cells during the cell cycle highlighting the formation of anaphase bridges and the formation of micronuclei (arrows).

Fig. 8.

Time-lapse live cells microscopy of cell cycle progression of an untreated A431-H2B-GFP cell. Representative microscopy images of fluorescent (GFP) A431cells expressing H2B-GFP. Phases of the cell cycle are indicated above sequential images of the same cell from interphase through mitosis to telophase. Time-lapse was taken on a Etaluma Lumascope LS720 microscope with a 40X objective (Olympus LUCPLFLN40X). Scale bar 20 m

One caveat for live imaging is the requirement for specialized equipment that may be expensive. Another important caution to mention is related to photo-damage. Mammalian cells expressing fluorescent proteins are sensitive to photo-damage and fluorescence photobleaching from high intensity light sources. Therefore, illumination intensity, duration and intervals must be strategically optimized for each protein type and cell line (Sivakumar et al. 2014). If cells are to be imaged over an extended period of time, special considerations must be made to ensure the maintenance of cell health during the assay (Sivakumar et al. 2014).

Other methods have also been developed for live cell cycle imaging. In 2008, Miyawaki and colleagues developed the Fluorescent Ubiquitination-Based Cell Cycle Indicator system (FUCCI) which enables different fluorescent proteins to be expressed at different stages of the cell cycle (Sakaue-Sawano et al. 2008). Since its initial introduction, this genetically encoded biosensor system has been modified to enable more efficient distinction of different stages of the cycle. Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) microscopy can also be used to visualize the cell cycle in living cells (Tsunoda et al. 2008). However, the use of DIC does not permit a high degree of subcellular resolution and does not enable visualization of different stages of the cell cycle. Advances in CRISPR-Cas9 technology have also introduced small guide RNAs as an emerging tool to visualize chromatin dynamics with high resolution (Qin et al. 2017).

Notably, Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy has been used to visualize the expression of target proteins at various stages of the cell cycle (Shi et al. 2019). STED permits real-time observation of live cells, structures and cell dynamics at a resolution below 50 nm (Kilian et al. 2018). STED overcomes spatial resolution limits caused by light diffraction by using an additional laser beam (Inavalli et al. 2019). A recent study used HeLa and the kidney cell line, COS7 to assess cytoplasmic calcium level response, an indicator of stress and an early-stage modality for various death pathways following live-cell STED nanoscopy. The group demonstrated that in studying live-cells, STED did not pose substantial short-term damage responses compared to non-STED conditions (Kilian et al. 2018). STED microscopy/nanoscopy is a promising technique with magnificent resolution. However, it comes with at a hefty price.

Spectral karyotyping

It is widely known that many carcinomas have aneuploid karyotypes (Dutrillaux 1995). Karyotypic aberrations can be assessed by chromosome spreads and comparative genomic hybridization to reveal heterogeneity across and within cancers (Albertson and Pinkel 2003). Spectral Karyotyping (SKY) is a cytogenetic technique that displays all 24 human chromosomes together and uses optical microscopy to simultaneously measure spectrally overlapping probes that hybridize to chromosomes (Guo et al. 2014). SKY is a chromosome-specific multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization (Fisher et al.) technique that visualizes condensed metaphase chromosomesby using coloured probes with specific fluorochrome patterns that hybridize to the DNA. SKY simultaneously displays all chromosomes in unique colors using only five fluorochromes, therefore, careful combinations must be used to ensure each chromosome is visualized in a distinct color. This approach enables the detection of several types of chromosomal alterations in diseases including hematological malignancies and solid tumors (Imataka and Arisaka 2012).

Analysis of chromosomal abnormalities using SKY can uncover a plethora of information including chromosomal translocations, complex rearrangements (Padilla-Nash et al. 1999) and allows the reconstruction of clonal evolution events during cancer progression (Padilla-Nash et al. 2001). Furthermore, SKY has been shown to be useful for the study of constitutional chromosome abnormalities arising from de novo balanced and unbalanced translocations that occur between small DNA regions, especially at telomere ends (Haddad et al. 1998; Ning et al. 1999; Schrock et al. 1997). SKY can also assist in identifying double minute chromosomes (paired acentric chromatin bodies), regardless of size and numbers (Padilla-Nash et al. 2006). Visually, translocations lead to two color differences on a derivative chromosome, whereas several translocations result in several color differences (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Display of the 24-colour spectral karyotype (SKY) hybridization of cutaneous T cell lymphoma cell line, Mac2A. A SKY reveals a diploid karyotype for Mac2A cells. The karyotype presented with the individual inverted 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (top left), the raw spectral image (top middle), and the SKY classified image (top right). The classified karyotype is presented with individual chromosome numbers indicated below. An example of a dicentric chromosome (der(15)t(2;15)(p11.2;p12)) indicated by the white arrow.

Although SKY allows rapid visualization and recognition of chromosomes and permits rapid fielding of chromosomal abnormalities, the technique has important limitations. First, it does not provide information on specific regions of a chromosome that is localized within a rearrangement (Padilla-Nash et al. 2006). With respect to homogenous staining regions and double minute chromosomes, these regions contain multiple genes that are tightly linked and cannot be resolved using SKY. Additional Florescent In-Situ Hybridization (FISH) with gene-loci probes are often required for that level of detailed analysis (Barenboim-Stapleton et al. 2005). While the SKY technique reveals which fragment of DNA has translocated to a novel region, the spectral image does not provide details as to which genes within the chromosome are affected by a rearrangement (Padilla-Nash et al. 2006). Therefore, small deletions, duplications and intrachromosomal inversions do not result in a distinguishable color change. The resolution for SKY has been demonstrated to capture aberrations between 500 and 2000 kb (Fan et al. 2000).

Genome sequencing to detect genomic instability

To accurately assess instability, defined as the rate of change in the genome (Lengauer et al. 1998), it is imperative to identify tumor heterogeneity as well as how mutations evolve over time. Detecting somatic mutations in the genome or measuring chromosomal biomarkers (micronuclei, lagging chromosomes, chromatin bridges etc.) in a cancer cell, unfortunately, does not give accurate information on the degree of this rate of change. Since high degree of heterogeneity is related to tumorigenesis and metastatic potential, it is imperative to accurately assess these mechanisms in tumor cells. The development of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technology has revolutionized the study of instability, enabling genome-wide and nucleotide-level analysis of alterations present in the cancer genome (Vogelstein et al. 2013). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is commonly used to identify chromosome copy number alterations, also known as aneuploidy (Raman et al. 2019). WGS uses next generation sequencing (NGS), a versatile platform that can be used to detect uniform or whole aneuploidies, as well as deletions and duplications (Wells et al. 2014). Current NGS protocols begin with (i) Whole genome amplification and barcoding of DNA fragments; (ii) Library preparation, purification, and templating; (iii) Loading and sequencing; (iv) Alignment of sequenced reads to reference genome; and (v) data analysis.

More recent advances in NSG and the amplification of the whole genome have led to the development of single-cell sequencing (sc-seq). Named the “Nature Method” in 2013 (Pennisi 2012), single cell sequencing has pushed the boundaries of studying genomic instability in its truest form as the rate of mutations in cancer. Specifically, scDNA-seq examines sequence information from a single cell and enables in-depth analysis of normal and tumor genomes using the short-reads (600 bases) on an Illumina platform. ScDNA-seq specializes in detecting cell-to-cell heterogeneity (Wen and Tang 2018), distinguishing a small number of cells from a population as well as defining cell lineage maps. In fact, the analysis of serially isolated or spatially separated samples provides information on the dynamics of clonality and intratumoral heterogeneity (de Bruin et al. 2014; Gerlinger et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2014). These parameters provide insight into understanding genomic instability by detailing a comprehensive view of the state of genomic aberrations.

Distinct processes promoting genomic instability are involved in the generation of structural variations, copy number alterations (CNAs), single nucleotide variations and small insertion/deletions. ScDNA-seq has the ability to quantify smaller CNAs and mutational landscapes that, unfortunately, techniques such as SKY are unable to resolve. ScDNA-seq can reveal aneuploidy, CNAs and mutations in cells isolated from cell lines, primary tumors, metastases, circulating tumor cells and malignant pleural effusion (van den Bos et al. 2018). The sequencing datasets permit systematic analysis into the influence of genomic instability and allows the extrapolation of biological mechanisms based on traces of DNA damage and repair processes left on nucleotide sequences, such as the highly error-prone alternative end-joining process. Furthermore, the analysis of samples isolated at different time points can provide information on the rate of change in a tumor (i.e., its instability).

In most cases, genome amplification is required for scDNA-seq, since a cell only has two copies of DNA and most sequencing technology is not yet sensitive enough to work with such small quantities of sample genome. Due to the limited amount of initial material, scDNA-seq has a number of limitations that includes coverage non-uniformity, allelic dropout (ADO) events, and false-positive errors (reviewed in Wang and Navin 2015). First, coverage non-uniformity is a result of under and over amplifications that may lead to inaccurate variant calling and false-negative somatic number variations. Secondly, allelic dropout occurs, when heterozygous variants experience dropout during the whole genome amplification resulting in a homozygous genotype. Lastly, random false-positive errors can arise from DNA polymerase creating somatic number variations or insertion/deletion errors during the amplification process. However, to address amplification methodology caveats, there are two scDNA-seq methods that can accomplish accurate sequencing without the use of gene amplification: PacBio and Oxford Nanopore. These third-generation sequencing technologies enable single cell sequencing using long-reads (10 kilobases) and thus preserve base modifications (Depledge et al. 2019) and provide more accurate and sensitive identification of structural variants (SV) and large-scale allele-specific copy number variants compared to Illumina based sequencing (Aganezov et al. 2020). This highlights the value of long-read sequencing for cancer genomes to achieve precise analysis of genetic instability.

Two ground-breaking studies in the early 2000’s, developed methodological approaches for genome-wide analyses of cancer genes in breast and colorectal cancers (Sjoblom et al. 2006; Wood et al. 2007). These studies were soon followed by the multi-institutional project called The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). TCGA has generated a plethora of genomic data of genome pairs (tumor and adjacent normal tissue) across 33 cancers. Since the development of scDNA-seq, the technique continues to be refined and used for novel analyses of cancers. One group of researchers developed the novel single-cell whole-genome amplification method to detect copy number variations at the kilobase level and therefore effectively detect mutations at a higher resolution (Chen et al. 2017). Another group developed a technique to analyze ploidy, copy number variations, and DNA methylation simultaneously, thereby examining altered functions and patterns of chromatin state and DNA methylation (Guo et al. 2017). These studies are of great importance for revealing how scDNA-seq technology can be adapted to study genomic instability.

Conclusion

The preservation of a stable genome is orchestrated by various safeguard mechanisms established through evolution. Deficiencies in these mechanisms can result in mutations and genomic instability, and their accumulation can ultimately affect protein production and activity correlating with phenotypic changes that affect cellular functions (Negrini et al. 2010). These changes have been known to lead to a variety of diseases including cancer. A plethora of studies have implicated the significance of genomic instability in the formation and progression of cancer. Since genomic instability is a characteristic of most cancers, the accurate and attainable evaluation of such instability is a vital asset to investigate meiomitosis and other mechanisms by which it contributes to tumor initiation and progression and influences the long-term effects of cell fate.

Despite ongoing advances and the ever-expanding knowledge of the mechanisms of tumorigenesis, there is still much about this process that remains largely elusive and controversial. How is an unstable genome associated with tumorigenesis? Is genomic instability a cause or a consequence of tumor evolution? Alterations in mechanisms of DNA damage repair, and cell cycle checkpoints are widely studied contributors to cancer. However, alterations in these mechanisms do not drive all cancer types and there is still much that remains elusive in carcinogenesis. We provide a framework of assays that can be used to assess DNA damage, centrosome aberrations, micronuclei, lagging chromosomes, chromatin bridges, whole chromosome duplications and other forms of genomic mutations.

Breakthroughs in cancer research are often accompanied by the use of a novel technique to answer a question that pushes the boundaries of current technologies. Research of genomic instability is no exception, from the development of the CBMN cytome assay, to the use of H2B-GFP to visualize DNA in live cell imaging to single-cell sequencing of cancer cells, these techniques pioneered to visualize genomic instability, providing a detailed view of the events not seen before. Thus, using a reliable and diverse set of techniques to evaluate genomic instability in cancer will provide further insight into its mechanisms with respect to novel proteins and treatments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

IVL designed and supervised the study. JG performed molecular experiments. JG, BR, MBR, DS, KR, LA, JHX, AMV, DJGO and IVL analyzed the data and prepared figures. JG and IVL wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to writing and review of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Project Scheme Grant #426655 to Dr. Litvinov, Cancer Research Society (CRS)-CIHR Partnership Grant #25343 to Dr. Litvinov, Canadian Dermatology Foundation research grants to Dr. Litvinov, and by the Fonds de la recherche du Québec–Santé to Dr. Litvinov (#34753, #36769 and #296643).

Data availability

All available data is published in the manuscript and detailed protocols are published in supplementary materials. All materials are commercially available.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Gantchev, Email: jennifer.theoret@mail.mcgill.ca.

Brandon Ramchatesingh, Email: brandon.ramchatesingh@mail.mcgill.ca.

Melissa Berman-Rosa, Email: melissa.bermanrosa@mail.mcgill.ca.

Daniel Sikorski, Email: daniel.sikorski@mail.mcgill.ca.

Keerthenan Raveendra, Email: keerthenan.raveendra@mail.mcgill.ca.

Laetitia Amar, Email: laetitia.amar@mail.mcgill.ca.

Hong Hao Xu, Email: hong-hao.xu.1@ulaval.ca.

Amelia Martínez Villarreal, Email: amelia.martinezvillarreal@mail.mcgill.ca.

Daniel Josue Guerra Ordaz, Email: daniel.guerraordaz@mail.mcgill.ca.

Ivan V. Litvinov, Email: ivan.litvinov@mcgill.ca

References

- Aaij R, Abellan Beteta C, Adeva B, Adinolfi M, Aidala CA, Ajaltouni Z, Akar S, Albicocco P, Albrecht J, Alessio F, et al. Measurement of antiproton production in p-He collisions at sqrt[s_{NN}]=110 GeV. Phys Rev Lett. 2018;121:222001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.222001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelaide J, Finetti P, Bekhouche I, Repellini L, Geneix J, Sircoulomb F, Charafe-Jauffret E, Cervera N, Desplans J, Parzy D, et al. Integrated profiling of basal and luminal breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11565–11575. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aganezov S, Goodwin S, Sherman RM, Sedlazeck FJ, Arun G, Bhatia S, Lee I, Kirsche M, Wappel R, Kramer M, et al. Comprehensive analysis of structural variants in breast cancer genomes using single-molecule sequencing. Genome Res. 2020;30:1258–1273. doi: 10.1101/gr.260497.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson DG, Pinkel D. Genomic microarrays in human genetic disease and cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(2):R145–R152. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato A, Lentini L, Schillaci T, Iovino F, Di Leonardo A. RNAi mediated acute depletion of retinoblastoma protein (pRb) promotes aneuploidy in human primary cells via micronuclei formation. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimzadeh J, Bornens M. Structure and duplication of the centrosome. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2139–2142. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SM, Murnane JP. Telomeres, chromosome instability and cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2408–2417. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfalvi G. Overview of cell synchronization. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;761:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-182-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfalvi G. Cell cycle synchronization: methods and protocols. New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Banfalvi G. Overview of cell synchronization methods in molecular biology. New York: Humana Press; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenboim-Stapleton L, Yang X, Tsokos M, Wigginton JM, Padilla-Nash H, Ried T, Thiele CJ. Pediatric pancreatoblastoma: histopathologic and cytogenetic characterization of tumor and derived cell line. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;157:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, West SC. Role of the human RAD51 protein in homologous recombination and double-stranded-break repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner SE, Wahl GM, Von Hoff DD. Double minute chromosomes and homogeneously staining regions in tumors taken directly from patients versus in human tumor cell lines. Anticancer Drugs. 1991;2:11–25. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonassi S, Neri M, Lando C, Ceppi M, Lin YP, Chang WP, Holland N, Kirsch-Volders M, Zeiger E, Fenech M, group, H. c. Effect of smoking habit on the frequency of micronuclei in human lymphocytes: results from the Human MicroNucleus project. Mutat Res. 2003;543:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonassi S, El-Zein R, Bolognesi C, Fenech M. Micronuclei frequency in peripheral blood lymphocytes and cancer risk: evidence from human studies. Mutagenesis. 2011;26:93–100. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone CW, Kelloff GJ. Development of surrogate endpoint biomarkers for clinical trials of cancer chemopreventive agents: relationships to fundamental properties of preinvasive (intraepithelial) neoplasia. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1994;19:10–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornens M. The centrosome in cells and organisms. Science. 2012;335:422–426. doi: 10.1126/science.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornens M, Gonczy P (2014) Centrosomes back in the limelight. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 10.1098/rstb.2013.0452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cannan WJ, Pederson DS. Mechanisms and Consequences of Double-Strand DNA Break Formation in Chromatin. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231:3–14. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SB. Effects of cytochalasins on mammalian cells. Nature. 1967;213:261–264. doi: 10.1038/213261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SL, Cibulskis K, Helman E, McKenna A, Shen H, Zack T, Laird PW, Onofrio RC, Winckler W, Weir BA, et al. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:413–421. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JY. A clinical overview of centrosome amplification in human cancers. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:1122–1144. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Hickson ID. On the origins of ultra-fine anaphase bridges. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3065–3066. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.19.9513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, North PS, Hickson ID. BLM is required for faithful chromosome segregation and its localization defines a class of ultrafine anaphase bridges. EMBO J. 2007;26:3397–3409. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Deng X. Cell synchronization by double thymidine block. Bio Protoc. 2018;8(17):e2994. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Guan J, Huang B. Imaging specific genomic DNA in living cells. Annu Rev Biophys. 2016;45:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Xing D, Tan L, Li H, Zhou G, Huang L, Xie XS. Single-cell whole-genome analyses by Linear Amplification via Transposon Insertion (LIANTI) Science. 2017;356:189–194. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Tang H, Chen X, Zhang G, Wang Y, Xie X, Liao N. Transcriptomic analyses identify key differentially expressed genes and clinical outcomes between triple-negative and non-triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:179–190. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S187151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JY, Kitano H, Takikita M, Cho H, Noh KH, Kim TW, Ylaya K, Hanaoka J, Fukuoka J, Hewitt SM. Synaptonemal complex protein 3 as a novel prognostic marker in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini D. Merotelic kinetochore orientation, aneuploidy, and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1786:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole R. Live-cell imaging. Cell Adh Migr. 2014;8(452):459. doi: 10.4161/cam.28348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornélio DA, Tavares JC, Pimentel TV, Cavalcanti GB, Jr, Batistuzzo de Medeiros SR. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay adapted for analyzing genomic instability of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:823–838. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, Pellman D. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature. 2012;482:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Adda di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, Fiegler H, Carr P, Von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Carter NP, Jackson SP. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Anna J. Synchronization of mammalian cells in S phase by sequential use of isoleucine-deprivation G1- or serum-withdrawal G0-arrest and aphidicolin block. Methods Cell Sci. 1996;18:115. [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin EC, McGranahan N, Mitter R, Salm M, Wedge DC, Yates L, Jamal-Hanjani M, Shafi S, Murugaesu N, Rowan AJ, et al. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science. 2014;346:251–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1253462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaval B, Doxsey SJ. Pericentrin in cellular function and disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:181–190. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denu RA, Zasadil LM, Kanugh C, Laffin J, Weaver BA, Burkard ME. Centrosome amplification induces high grade features and is prognostic of worse outcomes in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:47. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2083-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depledge DP, Srinivas KP, Sadaoka T, Bready D, Mori Y, Placantonakis DG, Mohr I, Wilson AC. Direct RNA sequencing on nanopore arrays redefines the transcriptional complexity of a viral pathogen. Nat Commun. 2019;10:754. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08734-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Gao Y, Yin L, Li Q, Li J, Chen H. Induction and inhibition of the pan-nuclear gamma-H2AX response in resting human peripheral blood lymphocytes after X-ray irradiation. Cell Death Discov. 2016;2:16011. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxsey SJ, Stein P, Evans L, Calarco PD, Kirschner M. Pericentrin, a highly conserved centrosome protein involved in microtubule organization. Cell. 1994;76:639–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxsey S, Zimmerman W, Mikule K. Centrosome control of the cell cycle. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutrillaux B. Pathways of chromosome alteration in human epithelial cancers. Adv Cancer Res. 1995;67:59–82. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond DA, Tucker JD. Identification of aneuploidy-inducing agents using cytokinesis-blocked human lymphocytes and an antikinetochore antibody. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1989;13:34–43. doi: 10.1002/em.2850130104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond DA, Rupa DS, Hasegawa LS. Detection of hyperdiploidy and chromosome breakage in interphase human lymphocytes following exposure to the benzene metabolite hydroquinone using multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization with DNA probes. Mutat Res. 1994;322:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Zein RA, Etzel CJ, Munden RF. The cytokinesis-blocked micronucleus assay as a novel biomarker for selection of lung cancer screening participants. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:336–346. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.05.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YS, Siu VM, Jung JH, Xu J. Sensitivity of multiple color spectral karyotyping in detecting small interchromosomal rearrangements. Genet Test. 2000;4:9–14. doi: 10.1089/109065700316417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantes P, Brooks R (1993) The cell cycle: a practical approach: IRL Press at Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Feichtinger J, Aldeailej I, Anderson R, Almutairi M, Almatrafi A, Alsiwiehri N, Griffiths K, Stuart N, Wakeman JA, Larcombe L, McFarlane RJ. Meta-analysis of clinical data using human meiotic genes identifies a novel cohort of highly restricted cancer-specific marker genes. Oncotarget. 2012;3:843–853. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. The cytokinesis-block micronucleus technique and its application to genotoxicity studies in human populations. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(Suppl 3):101–107. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. The in vitro micronucleus technique. Mutat Res. 2000;455:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1084–1104. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M, Morley AA. Measurement of micronuclei in lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 1985;147:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(85)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M, Morley AA. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus method in human lymphocytes: effect of in vivo ageing and low dose X-irradiation. Mutat Res. 1986;161:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M, Holland N, Chang WP, Zeiger E, Bonassi S. The human micronucleus project–an international collaborative study on the use of the micronucleus technique for measuring DNA damage in humans. Mutat Res. 1999;428:271–283. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher H, Harding S, Hickman M, Macleod J, Audrey S. Barriers and enablers to adolescent self-consent for vaccination: a mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Vaccine. 2018;37(3):417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund A, Orjalo AV, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Bandi M, Nitta M, Ivanova EV, Bronson RT, Pellman D. Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53-null cells. Nature. 2005;437:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature04217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachechiladze M, Skarda J, Soltermann A, Joerger M. RAD51 as a potential surrogate marker for DNA repair capacity in solid malignancies. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1286–1294. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, Pellman D. A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature. 2009;460:278–282. doi: 10.1038/nature08136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantchev J, Martinez Villarreal A, Gunn S, Zetka M, Odum N, Litvinov IV. The ectopic expression of meiCT genes promotes meiomitosis and may facilitate carcinogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2020;19:837–854. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2020.1743902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayathri B, Kalyani R, Hemalatha A, Vasavi B. Significance of micronucleus in cervical intraepithelial lesions and carcinoma. J Cytol. 2012;29:236–240. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.103941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann SM, Schramke V, Pedersen RT, Gallina I, Eckert-Boulet N, Oestergaard VH, Lisby M. TopBP1/Dpb11 binds DNA anaphase bridges to prevent genome instability. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:45–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giehl M, Fabarius A, Frank O, Hochhaus A, Hafner M, Hehlmann R, Seifarth W. Centrosome aberrations in chronic myeloid leukemia correlate with stage of disease and chromosomal instability. Leukemia. 2005;19:1192–1197. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselsson D, Jonson T, Petersen A, Strombeck B, Dal Cin P, Hoglund M, Mitelman F, Mertens F, Mandahl N. Telomere dysfunction triggers extensive DNA fragmentation and evolution of complex chromosome abnormalities in human malignant tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12683–12688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211357798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godinho SA, Pellman D. Causes and consequences of centrosome abnormalities in cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1650):20130467. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve KB, Lindgreen JN, Terp MG, Pedersen CB, Schmidt S, Mollenhauer J, Kristensen SB, Andersen RS, Relster MM, Ditzel HJ, Gjerstorff MF. Ectopic expression of cancer/testis antigen SSX2 induces DNA damage and promotes genomic instability. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Han X, Wu Z, Da W, Zhu H. Spectral karyotyping: an unique technique for the detection of complex genomic rearrangements in leukemia. Transl Pediatr. 2014;3:135–139. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2014.01.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Li L, Li J, Wu X, Hu B, Zhu P, Wen L, Tang F. Single-cell multi-omics sequencing of mouse early embryos and embryonic stem cells. Cell Res. 2017;27:967–988. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Bai Y, Zhao M, Zhou M, Shen Q, Yun CH, Zhang H, Zhu WG, Wang J. Acetylation of 53BP1 dictates the DNA double strand break repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:689–703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad BR, Schrock E, Meck J, Cowan J, Young H, Ferguson-Smith MA, du Manoir S, Ried T. Identification of de novo chromosomal markers and derivatives by spectral karyotyping. Hum Genet. 1998;103:619–625. doi: 10.1007/s004390050878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halicka HD, Huang X, Traganos F, King MA, Dai W, Darzynkiewicz Z. Histone H2AX phosphorylation after cell irradiation with UV-B: relationship to cell cycle phase and induction of apoptosis. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch EM, Fischer AH, Deerinck TJ, Hetzer MW. Catastrophic nuclear envelope collapse in cancer cell micronuclei. Cell. 2013;154:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Gnawali N, Hinman AW, Mattingly AJ, Osimani A, Cimini D. Chromosomes missegregated into micronuclei contribute to chromosomal instability by missegregating at the next division. Oncotarget. 2019;10:2660–2674. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning W, Stürzbecher HW. Homologous recombination and cell cycle checkpoints: Rad51 in tumour progression and therapy resistance. Toxicology. 2003;193:91–109. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Palevitz BA. Metabolic inhibitors block anaphase A in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1995–2005. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.6.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffelder DR, Luo L, Burke NA, Watkins SC, Gollin SM, Saunders WS. Resolution of anaphase bridges in cancer cells. Chromosoma. 2004;112:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Chromoanagenesis and cancer: mechanisms and consequences of localized, complex chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Med. 2012;18:1630–1638. doi: 10.1038/nm.2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Jiang L, Yi Q, Lv L, Wang Z, Zhao X, Zhong L, Jiang H, Rasool S, Hao Q, et al. Lagging chromosomes entrapped in micronuclei are not 'lost' by cells. Cell Res. 2012;22:932–935. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka G, Arisaka O. Chromosome analysis using spectral karyotyping (SKY) Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012;62:13–17. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9285-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inavalli V, Lenz MO, Butler C, Angibaud J, Compans B, Levet F, Tønnesen J, Rossier O, Giannone G, Thoumine O, et al. A super-resolution platform for correlative live single-molecule imaging and STED microscopy. Nat Methods. 2019;16:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T, Sullivan KF, Wahl GM. Histone-GFP fusion protein enables sensitive analysis of chromosome dynamics in living mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C, Xu Q, Martin TD, Li MZ, Demaria M, Aron L, Lu T, Yankner BA, Campisi J, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science. 2015 doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian N, Goryaynov A, Lessard MD, Hooker G, Toomre D, Rothman JE, Bewersdorf J. Assessing photodamage in live-cell STED microscopy. Nat Methods. 2018;15:755–756. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch-Volders M, Sofuni T, Aardema M, Albertini S, Eastmond D, Fenech M, Ishidate M, Jr, Kirchner S, Lorge E, Morita T, et al. Report from the in vitro micronucleus assay working group. Mutat Res. 2003;540:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H, Chung JY, Noh KH, Lee YH, Kim TW, Lee SH, Eo SH, Cho HJ, Choi CH, Inoue S, et al. Synaptonemal complex protein 3 is associated with lymphangiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer patients with lymph node metastasis. J Transl Med. 2017;15:138. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner RE, Verma P, Molloy KR, Chait BT, Kapoor TM. Chemical proteomics reveals a gammaH2AX-53BP1 interaction in the DNA damage response. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:807–814. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]