Abstract

eHealth technologies play a role in the development of integrated care models for people living with Parkinson disease by improving communication with their health care teams and support self-care practices in a personalized way. This article presents a co-design approach to designing an eHealth technology, the eCARE-PD platform, that addresses the needs and expectations of people living with Parkinson disease, generates tailored care tips, and recommends actions for managing care priorities at home. We use a co-design approach involving four main iterative phases: (1) preparation, (2) mapping, (3) testing and using, and (4) co-producing solutions and requirements. This approach uses several methods to engage people directly to design this technology. The study allowed us to identify design principles to be integrated in the development of the eCARE-PD platform. These principles incorporate the expectations of future users, which were expressed during the iterative phases of the co-design process: (a) six key design features based on users’ needs and expectations, (b) six main issues users raised during a test at home and key features for improving the design of the eCARE-PD platform, and (c) collective solutions to design an interactive, meaningful, tailored, empathic, and socially acceptable technology. The results of the successive phases of the co-design process allow us to underline the progressive constitution of a technology defined over successive iterations as a digital companion supporting the self-care process at home and having the capacity to generate tailored digital health communication.

Keywords: eHealth, self-care, tailored messages, integrated care, codesign, Parkinson disease

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive, neurological disorder that results in impaired mobility, cognition, communication, or emotional well-being. The challenge for people living with Parkinson's disease (PwPs) is to preserve their independence and maintain a quality of life (QoL) for as long as possible. To do so, PwPs need to find a balance between their medical needs, such as monitoring and controlling their symptoms, and meeting their social needs and continuing to independently perform their activities of daily living. Accordingly, PwPs want support from health care providers to deal with symptoms and to adjust their life and daily activities in order to maintain their autonomy and QoL.1,2 Also, PwPs need guidance and practical advice to help self-manage the goals of their care.3,4 Generally, the number of self-care-related tasks increases with the progression of the condition, and informal caregivers play an important role. Self-care “refers to the activities that people living with chronic condition (patients and carers) undertake to manage the condition outside of institutionalized or professional care and as part of their everyday life.” 5: 869 For PwPs, self-care includes the following activities: observing changes in the body, acting on symptoms, managing treatment, and dealing with the psychological, physical, and social consequences of living with PD. Patients and caregivers monitor health signs and symptoms, interpret information, and take action such as exercising, managing diet, and asking for community resources.

eHealth technologies are useful for helping PwPs to adjust their self-care over time and find practical and personalized advice for managing their disease at home. In addition, eHealth technologies play a role in the development of integrated care models for PwPs, possibly improving care management in a personalized way and supporting self-care practices.6,7 Some solutions, such as mobile applications and wearable devices, are made to help PwPs manage their condition themselves. But, some researchers argue that to support self-care using PD eHealth technologies ought not be designed for individual use only, but also to sustain a collaborative approach of self-care that involves health care providers and informal caregivers.5,8

eHealth technologies may be useful tools for PwPs, by encouraging self-management practices and self-care at home. Numerous eHealth technologies have been specifically designed for PD such as those (a) providing information on the disease and targeting patients, families, and informal caregivers; (b) including tests for assessing various physical or cognitive symptoms of PD such as gait, tremor, speech; and (c) providing guidelines for treatment including medication management and cognitive or speech therapy.9–11 There is evidence indicating that eHealth technology can be effective or at least promising for supporting self-care in PD in the context of an integrated care model.7,9 For example, various mobile health technologies or wearable technologies are available to support remote monitoring of PD motor symptoms, to support PwPs with diagnosis-specific information and treatment, or to increase medication adherence.12–14 Technologies for PD involving self-tracking systems have traditionally focused on self-monitoring motor symptoms, mental health, medication adherence to gain health-related self-knowledge or achieve a health-related goals. In the context of integrated care, however, there is a need to adopt a holistic approach of self-care that does not focus only on medical care, but also takes into consideration the PwP's social care and well-being.

The opportunities offered by eHealth technologies open new horizons for self-care that help PwPs collect and track relevant information for the purpose of getting personalized support and advice. As stated by Cornet et al., 15 an effective design of eHealth technologies supporting self-care practices should support all three stages of self-care, monitoring, interpretation, and action. In addition, personalized care is necessary to optimize care management models such as eHealth technologies tailored to individual's needs. 16 Indeed, self-care can be improved by designing eHealth technologies to provide personalized provision of tips and care resources to PwPs. 17 As stated by van Halteren et al. 16 : S17:

It is foreseeable that a virtual care manager system, based on standardized protocols and enhanced by artificial intelligence can soon replace some tasks and responsibilities of human personnel, e.g., by answering common questions and by providing information tailored to the issues raised.

Most studies assessing eHealth technologies for PD reported high attrition rate, because many technological solutions “looking to solve a problem” rather than developing solutions based on the actual needs of PwP. 18 For example, in the study by de Silva de Lima et al. 19 , the attrition rate was 27% after 6 weeks’ study period. PD technologies still have a tendency to prioritize the physician's perspective, while the needs of PwPs and informal caregivers are not be fully supported.8,20 And as stated by Riggare et al. 18 : “Active involvement of PwP as an equal partner in digital health development needs to be the norm, and if necessary mandated and/or incentivized.”4,18

In addition, engaging PwPs, caregivers, and health care professionals in the design of digital health technologies supporting self-care practices in a personalized way is crucial to ensure that care resources generated by the technology meet the needs and expectations of PwPs.21,22 The question that arises is: how should a personalized eHealth technology be designed to support self-care and promote integrated care for PwPs? To answer this question, this article presents a co-design approach that underlines the progressive constitution of an eHealth technology defined over successive iterations as a digital companion supporting self-care and having the capacity to generate tailored digital health communication.

Methods

Context of the study: The iCARE-PD project

The needs for clinical management, monitoring, and coordination of the provision of care for PwP are a major challenge for healthcare organizations. Poorly coordinated access to home care services places great strain on people living with this disease, as they face significant barriers to accessing certain services in a fragmented health system. The iCARE-PD project aims to study the design and implementation of an integrated care model for PwPs. 23 This model is based on coordinated care among the different care providers (integrated care), the implementation of a program of self-management of care by patients, their informal caregivers, and professional providers, and the design and implantation of eHealth technologies. One of the goals of this project is therefore to design an eHealth platform called eCARE-PD, using a co-design or participatory design approach.24,25 This platform seeks to enable PwPs to follow—in collaboration with their care team and their caregivers—their care priorities, to access medical and social resources, and to receive personalized advice. Thus, eCARE-PD is in a way a digital companion to accompany, guide, and help PwPs to self-manage their lives, their disease, and its consequences at home.

A co-design approach

The methodology implemented is based on a co-design approach that includes several iterative cycles during which patients, informal caregivers, and health care providers are considered full partners in the design process. Our approach is part of the tradition of Scandinavian participatory design, which commits us to moving away from a purely techno-centric approach. 26 In other words, it is not a question of focusing our attention solely on the development of a digital health technology but of taking into account the anticipated and actual uses as well as the changes that patients may bring to the design of a technology that could affect their daily lives and the management of their disease. The different stakeholders in the co-design process will share ideas and points of view, negotiate, and make design decisions that will implicitly or explicitly inject certain values and expectations into the final product. 27 Thus, involving future potential users as co-designers in the design process significantly increases the chances of developing a technology that will represent the values and the meaning that future users give to it. A co-design or participatory design approach is based on fundamental principles of engagement, respect for lived experiences, collaboration, and creativity. 28 It is a “process of investigating, understanding, reflecting upon, establishing, developing, and supporting mutual learning between multiple participants in collective reflection-in-action.”24: 2 Any co-design process involves successive iterations that will gradually integrate user expectations and also respond to tensions and problems that might emerge during the technology's development cycle. Problems may be related to the practical or social acceptability of this technology.29–31

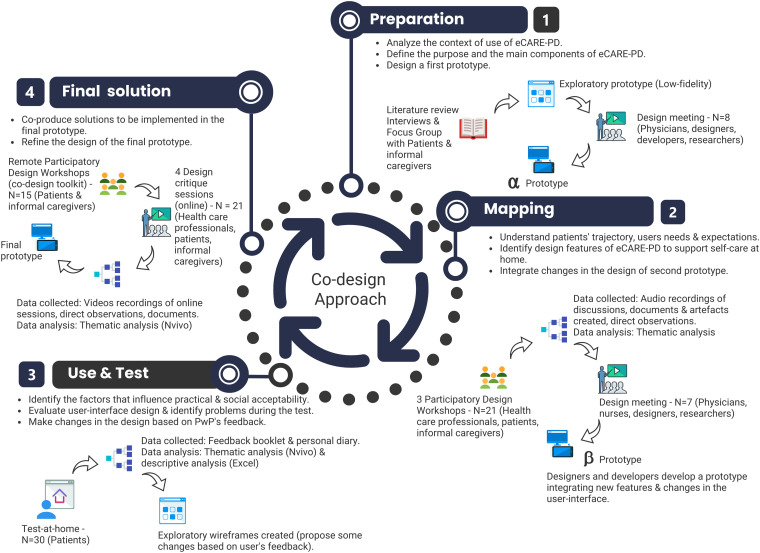

A co-design approach involves several development cycles and the use of various methods that will allow open space for constant dialogue with future users, throughout the development of the technology (Figure 1). Our design process includes four phases, and within each of these phases, the development cycle was based on three fundamental actions: (1) analyze, do, or evaluate; (2) negotiate and decide; and (3) design and prototype. In our case, participants were asked to collaborate in the design process through organized participatory design workshops or prototype home-testing activities. During the workshops, various facilitation techniques were used to engage participants.32,33 These techniques combine three activities: (a) telling (e.g., sharing experiences of living with the disease using a “Journey Mapping” activity; using a personal journal to share experiences of using the prototype); (b) doing (interacting with a prototype when testing prototypes and redrawing screens); and (c) stage possible futures (imagine and represent future solutions and use cases during critical design sessions).

Figure 1.

Overview of the co-design approach.

The co-design process took place between October 2019 and March 2021. In March 2020, we had to adapt our approach to the health situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to favoring remote co-design workshops. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board (Protocol # 20180561-01H). All participants were given an information sheet and were assured that their data would be treated confidentially. Written and oral informed consent was obtained prior to any data collection.

Preparation phase

A literature review aimed at identifying both the self-management/self-care technologies developed to support PwPs and understanding what makes these technologies practically and socially acceptable for users 31 was conducted. We also used the results of a study carried out in 2017–2018 with PwPs, caregivers, and health professionals, which had the double goal of better understanding the needs and self-care practices of patients and of identifying what expectations they had of eHealth technologies. 34 This information allowed us to better understand the context of use of future eHealth technologies that would be designed and to identify the role such technologies might play within the framework of an integrated care model for PwPs. This preliminary work enabled the creation of an exploratory, low-fidelity prototype, which served to support a first design meeting with doctors, designers, and developers. The aim of this meeting was to better define the platform's goals and to clarify with the doctors and designers what functionalities needed to be integrated into it. These discussions provided an overview of the eCARE-PD platform and its features, which initially included: (a) a page where users identify and select the health priorities they wish to monitor (Care Priorities); (b) a self-tracking tool that allows them to assess their health priorities on a scale (Priority Tracker) and to receive recommendations and care tips; (c) access to care resources (Resources); and (d) a care path shared with their medical teams (Care Plan). Thus, the platform's goal is to provide patients with access to resources, personalized advice to help and support them in their self-care process at home. To do this, they can access a tool they use themselves to track the health priorities that they deem important to monitor and for which they want to receive personalized advice that will help them daily to manage the effects of their disease.

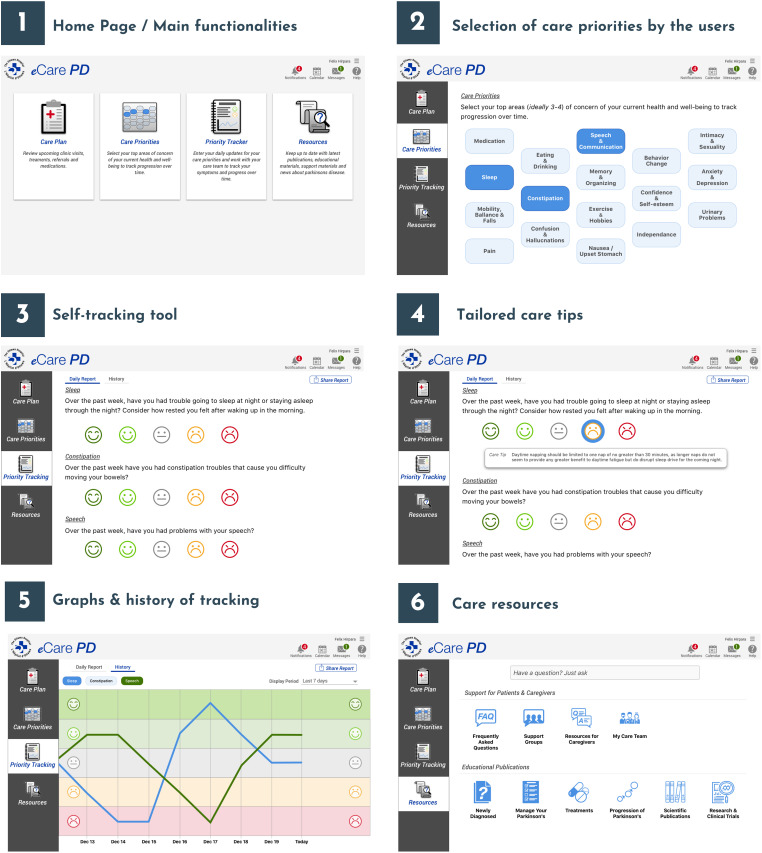

At the end of the design meeting, certain elements of the exploratory prototype were discussed, redefined, clarified, and reworked. This enabled the team of designers to create the α prototype that was presented to and subsequently discussed, in participatory design workshops, with the patients and their informal caregivers (see Figure 2). In other words, the first prototype served as a building block that would guide the development of the future versions of the eCARE-PD platform.

Figure 2.

The preliminary functionalities (α prototype).

eCARE-PD is a platform that will allow PwPs to receive personalized advice or care resources. For this, the user will first define his profile and needs. Some health data (e.g. sensor data or self-reported data) will be collected by the platform and the user will receive tailored health messages (tailored care tips) and recommendation (personalized care resources). The user also has access to charts and data that allow him to track and share his health data with his medical team.

Mapping

For the mapping cycle, heterogeneous purposive sampling was used to select PwPs for the study. Healthcare professionals were purposively sampled to include professionals who work directly with PwP. The participatory design workshops included 21 participants in total (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (mapping).

| Participants (N = 21) | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Patients—N = 10 | H&Y stage [1–3] Age [50–78] Gender [Female: 2—Male: 8] |

| Informal caregivers—N = 6 | Age [55–70] Gender [Female: 4—Male: 2] |

| Nurses—N = 3 | Nurse coordinator: 1 Registered nurses: 2 |

| Physicians—N = 2 | Neurologists specialized in PD |

We organized three participatory design workshops, including a workshop bringing together health professionals (doctors and nurses working at the The Ottawa Hospital Parkinson disease and movement disorders center) and two other workshops bringing together PwPs (single patients or patients accompanied by their informal caregivers). More specifically, the goal of these workshops was to understand and specify the context of use of the eCARE-PD platform by allowing patients through an activity (Trajectory Mapping) to discuss their experiences with the disease as well as their daily needs and challenges. The discussions around the Trajectory Mapping activity also made it possible to collectively imagine future uses of this yet-to-be-designed technology, so that it could accompany patients and support them on their path. Then, patients and caregivers were invited to discuss the functionalities that would be integrated into the eCARE-PD platform; this they did by interacting with the α prototype: as they browsed through pages, they commented on them and made their suggestions for changing some functionalities and the interface design. During their interaction with the α prototype, participants shared their views about the self-monitoring system.

We took pictures of the different artifacts created by the participants during the workshop (e.g. sketches with changes in user-interfaces, written recommendations). With the participants’ consent, all of the discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed word for word, and anonymized. A manual thematic analysis was carried out by following a systematic process of sorting the data into key themes using five stages: familiarization; developing a thematic; indexing; charting; and mapping and interpretation. 35 After organizing the data from the workshops into themes and subthemes, the main themes were translated into design features. The analysis of the data collected during the mapping cycle allowed us to integrate the suggestions made by the participants into a β prototype.

Use and test

Purposive sampling was used to select participants for the use and test. Sampling criteria were developed in collaboration with our tertiary PD center to ensure adequate sampling in terms of gender, PD stage, age, and language. The home test included 30 participants in total (Table 2). Participants from the first phase were contacted and included in the sample but their participation was on a voluntary basis. We also added additional participants to increase our sample. eCARE-PD was not developed for advanced PD patients with significant loss of autonomy (dementia or in a bed-ridden status), it is a tool for self-care and for supporting care integration. It is also for this reason that participants with a stage 1–3 are representative of future users of the technology.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants (use & test).

| Participants | Gender | Age | H&Y stage | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 30 | Female: 8 Male: 22 |

[50–60] = 7 [61–70] = 8 [71–80] = 14 [81–85] = 1 |

Stage 1: 3 Stage 2: 21 Stage 3: 6 |

English: 16 French: 14 |

The participants were invited to test the β prototype at home for 3 weeks and to provide feedback during the testing phase. The purpose of the home test was to assess the technology's usability and to identify which factors influence its practical and social acceptability in order to determine the changes that needed to be made to design an acceptable tool. Instructions were given verbally as well as in writing by the nurse, to support the patients’ understanding. To provide their feedback, each participant received a printed booklet divided into three parts: (1) utilizability and usability of eCARE-PD (a short survey with Likert scale and open comments); (2) the use of eCARE-PD in daily life (open questions and personal comments); (3) feedback grid (open comments and suggestions about the design).

Responses to the first part of the feedback booklet were compiled into an Excel file and organized in descriptive tables presenting the survey results relating to the usability of the platform. The participants’ written comments were all transcribed and entered into Nvivo 12 for Mac for thematic analysis. The thematic analysis framework involved both inductive and deductive coding. For the deductive code framework, we used the main usability dimensions (e.g. usefulness, guidance, interactivity, personalization) defined in previous studies.36–38 We also enriched this type of coding with our inductive analysis by revealing specific dimensions related to social acceptability (e.g. warm technology, meaningful use, data valence). Based on the comments and suggestions received, the research team created wireframes, incorporating in the design some changes proposed by the users. The results of the home test and those wireframes were used to stimulate discussion during the design critique sessions that were held during the last phase of the co-design process.

Final solution

The goal of this last cycle was to improve the eCARE-PD platform by collectively identifying solutions that should be implemented in the final prototype. The previous cycle (test & use) revealed issues in the usability of the platform. This is common and expected during a co-design process, since the purpose is to identify the difficulties and problems during the different development cycles so they can be discussed collectively and thus generate solutions. It was therefore the goal of the co-design process to collectively identify solutions to the problems that emerged during the previous cycle. To accomplish this, we first conducted remote participatory design workshops with a group of users of the platform, and the next step was to organize online design critique sessions, that is, three sessions with patients (alone and with informal caregivers) and one session involving health care providers and researchers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants’ characteristics (final solution).

| Participants (N = 21) | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Patients—N = 15 | H&Y stage [1–3] Age [50–80] Gender [Female: 3—Male: 12] |

| Healthcare providers—N = 4 | Nurse coordinator: 1 Neurologists specialized in PD: 3 |

| Social scientists—N = 2 | Health communication expert: 1 Psychologist: 1 |

Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the participatory design workshops were conducted remotely. One week before each workshop, an email with clear instructions and a co-design toolkit was sent to the participants. The co-design toolkit invited these participants (alone or with their informal caregiver) to complete two activities at home to be prepared for the design critique session that would take place online: (a) a “fishbone diagram” to identify problems on eCARE-PD features and user-interfaces accompanied by solutions to improve them; (b) CARD sorting tool to refine the content of the care resources available in the eCARE-PD platform. The results of the two activities carried out at home were shared with the researchers during the online design critique session. The participants were also able to share their feedback and user interface design solutions via an online Google form. The design critique sessions were intended to evaluate the eCARE-PD prototype and provide design solutions by focusing on the homepage and the selection of care priorities; the tracking tool and personal report (data visualization); and the personalized care tips and care resources.

All of the discussions that took place during the workshops were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed transcribed and entered into Nvivo 12 for Mac to organize and manage the data for thematic analysis. 35 A thematic analysis was carried out in order to highlight the solutions proposed and collectively negotiated during the critical design sessions. Then, the proposed solutions were integrated into a final prototype. The initial coding was conducted independently by the researcher that led the workshops. Themes were identified, reviewed, and refined through researcher discussion and agreement. The analysis was further refined through discussions with co-authors throughout the process.

Results

In this section, the results are presented in three parts to highlight the main findings at the end of each co-design cycle. First, we highlight the key design features identified during the mapping cycle, which were used to design a new prototype. Second, we reveal the problems and difficulties identified during the use of the prototype at home (use and test cycle). And finally, the problems were discussed during the last cycle of the co-design process in order to collectively produce the final design requirements and suggest solutions to improve the eCARE-PD platform. The presentation of the results of the three successive cycles of the co-design process allowed us to highlight the progressive development of a platform designed with PwPs.

Mapping: Six main themes mapping the main features of eCARE-PD platform

Our study's mapping cycle allowed us to identify key design features needing to be integrated in the design and development of this technology. These design features incorporate the expectations of future potential users, which they expressed during the participatory design workshops. Table 4 summarizes the findings identified through the thematic analysis and the themes related to design recommendations that were used to guide the development of the β prototype.

Table 4.

Six main themes and recommendations.

| Themes | Summary | Main recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Customizable and engaging | Because the disease manifests itself very differently in each individual, the more ‘customizable’ tool is, the more useful it will be. One of the things about Parkinson's is that it's very individualistic, so you have to sort of address different situations for different people, and so the more customizable it is the better is, but with a broad framework to help people do it. [Patient] One of the things about Parkinson's is that it's very individualistic, so you have to sort of address different situations for different people, and so the more customizable it is the better is, but with a broad framework to help people do it. [Patient] But it might be nice to have those customizable so that you can put your own priorities, and your own areas, and organize them in such ways that you can. [Patient] But it might be nice to have those customizable so that you can put your own priorities, and your own areas, and organize them in such ways that you can. [Patient]

Increase engagement by focusing on action and practical advice to support self-care at home.  My care plan is goals, but it's actions too. It's more active, it's my actions. Action in terms of taking medication, action in terms of speech therapy, it's action to be. [Patient] My care plan is goals, but it's actions too. It's more active, it's my actions. Action in terms of taking medication, action in terms of speech therapy, it's action to be. [Patient]

|

|

| Use of visualization as an intervention | Visualization is intended to provide PwP with an awareness of the historical evolution of their disease and to help them to manage their condition at home. I think that the graphing for me was important for me actually, the lines, because when he first got diagnosed, I tracked everything from his diet, to his vitamins, to his intake of water; absolutely everything to figure out how to manage any symptoms. [Patient]

I think that the graphing for me was important for me actually, the lines, because when he first got diagnosed, I tracked everything from his diet, to his vitamins, to his intake of water; absolutely everything to figure out how to manage any symptoms. [Patient]

Add contextual information to improve utility of visualization.  The graph is very important for caregivers. Low and Hight, I would like to add notes, because I need to add more details. I’d like to see a pattern or not. [Informal Caregiver] The graph is very important for caregivers. Low and Hight, I would like to add notes, because I need to add more details. I’d like to see a pattern or not. [Informal Caregiver] Will I be able to will there be an option to put comments on each, I think you should be able to see, if you’re not sleeping a week at a time, click on the comments to see what's causing that, the sleep problem, not just that you’re not sleeping for a month or something like that. [Patient]

Will I be able to will there be an option to put comments on each, I think you should be able to see, if you’re not sleeping a week at a time, click on the comments to see what's causing that, the sleep problem, not just that you’re not sleeping for a month or something like that. [Patient] On the graph, the ability to red flag certain things would be good. You know when we’re talking to the doctors and it's, this month was particularly bad, well why was it bad? So if you’re able to red flag certain days as being worst, and then it would be, like, I know it's weird, but I find he feels worst in certain months. [Informal Caregiver] On the graph, the ability to red flag certain things would be good. You know when we’re talking to the doctors and it's, this month was particularly bad, well why was it bad? So if you’re able to red flag certain days as being worst, and then it would be, like, I know it's weird, but I find he feels worst in certain months. [Informal Caregiver]

Confusion due to the lack of clarity.  I find it too confusing if you get two lines on the same. Preferably I would find it, it's easier to read [Health Care Provider] I find it too confusing if you get two lines on the same. Preferably I would find it, it's easier to read [Health Care Provider]

Possibility to share data with physician before medical appointment and using data recorded for improving communication with HCP during follow-up.  Which one doing the reporting? Sharing the platform could be useful. [Informal Caregiver]. Yes, I don’t have memory. So I don’t remember, so if her could report for me. It's good. [Patient] Which one doing the reporting? Sharing the platform could be useful. [Informal Caregiver]. Yes, I don’t have memory. So I don’t remember, so if her could report for me. It's good. [Patient]

|

|

| Provide tailored care tips and personalized care resources | Personalized health messages or notifications to keep motivated (e.g. physical activity, social activity) or to have practical tips or advice (e.g. educational messages). My physical activity sucks, so having this tell me that I need to do more physical activity would motivate me. Cause you know, sometimes I’ll be depressed and not motivated, but having something do that - that's nice. [Patient] My physical activity sucks, so having this tell me that I need to do more physical activity would motivate me. Cause you know, sometimes I’ll be depressed and not motivated, but having something do that - that's nice. [Patient] based on patterns, it is recommended that you take the following action. [Patient]

based on patterns, it is recommended that you take the following action. [Patient]

|

|

| Informative and interactive | Providing interactive educational resources about disease progression, symptoms, side effects of medication, treatments available, social impact of PD. One of the resources that you need to be sure you have looked at when you’re looking at the symptoms is that little book about understanding non motor behavior. Non motor symptoms. [Patient] One of the resources that you need to be sure you have looked at when you’re looking at the symptoms is that little book about understanding non motor behavior. Non motor symptoms. [Patient]

Support navigation to local resources (e.g. support groups, social worker, medical equipment, physiotherapist, etc.).  When we’re looking for support groups, it needs to be more defined. Because most support groups are for older people, and he needs to connect with other people with Parkinson's his age, because they won’t have the same issues he does. [Informal Caregiver] When we’re looking for support groups, it needs to be more defined. Because most support groups are for older people, and he needs to connect with other people with Parkinson's his age, because they won’t have the same issues he does. [Informal Caregiver]

|

|

| Straightforward and responsive tool | A platform easy to use and as simple as possible I’ll start by saying like the platform should be kept as simple as possible. So the less information you show, just show the right information. So the less you show the better it is. So the first screen is too much data, and it's not organized well enough to be able to understand the, what you’re trying to convey as a message, (inaudible) in terms of information. [Patient] I’ll start by saying like the platform should be kept as simple as possible. So the less information you show, just show the right information. So the less you show the better it is. So the first screen is too much data, and it's not organized well enough to be able to understand the, what you’re trying to convey as a message, (inaudible) in terms of information. [Patient]

Provide more instructions to guide the user.  It's complicated to use it and not clear how to navigate from one page to the next. [Patient]

It's complicated to use it and not clear how to navigate from one page to the next. [Patient]

Layout too busy with too much information  It's very busy, and I don’t know if there's an order here that's a random order, because the care priorities, these would all be part of care priorities I would think. [Patient] It's very busy, and I don’t know if there's an order here that's a random order, because the care priorities, these would all be part of care priorities I would think. [Patient]

|

|

| Collaborative tool | Patient and informal caregivers collaboratively achieve their self-care in everyday life. Informal Caregiver: Which one doing the reporting? Sharing the platform could be useful. Informal Caregiver: Which one doing the reporting? Sharing the platform could be useful.

Patient: Yes, I don’t have memory. So I don’t remember, so if her could report for me. It's good. |

|

Note. Based on the themes, we provided recommendations suggested by the participants during the participatory design workshops that should be considered when designing the next prototype of eCARE-PD.

In summary, during the participatory design workshops, participants had the opportunity to talk about their trajectory with PD. They were also asked to anticipate possible uses of a technology designed to accompany and support PwPs on a daily basis in the management of the disease. In the discussions that took place during the trajectory mapping activity, a consensus emerged very quickly: PD is not just about symptoms; its impact is much broader: it affects a patient's social life, personal life, and self-image. The participants very quickly expressed the complexity of this disease and the need to develop a holistic approach to the disease that should also be reflected in eCARE-PD's design. Indeed, living with PD means learning to live with intermittent periods of loss of autonomy, social isolation, depression, and reappearance of symptoms. In other words, it is living with an unpredictable disease that can progress slowly and have few symptoms or evolve quickly and have a huge impact on daily and family life. For participants, it is as much a lifestyle disorder, as it were, as it is a neurological disorder.

I would say it's an insidious disease that slowly takes away your ability to do the things that you normally do, without warning you. It's maybe overall (inaudible), it's scary because, like, there's something I think I can do that I can’t do, like last night I dropped three (inaudible). (Patient, Participatory Design Workshop 2)

Some days I just try really hard to convince myself to get out and do things, and, because I’m tired all the time, and I think from that perspective, you convince yourself that you can get out, and then once you’re out you’re fine, but it's really hard to convince yourself that you should get out and, you know, go for a run. (Patient, Participatory Design Workshop 1)

Based on these discussions around their multiple trajectories with the disease, participants were able to better define the role that a platform such as eCARE-PD could play in the journey of their care. Thus, the technology to be designed should not only help them manage symptoms but maintain their QoL and independence for as long as possible. The social, emotional, and relational aspects of living with Parkinson's disease also belong among the elements to be integrated into a self-monitoring and recommendation-providing platform. Thus, imagining the role that this technology could play in the future and what uses it could support led them to discuss the characteristics and functionalities that should be integrated into the platform. It was indeed at the time of the participatory design workshop—during which they could interact with the α prototype and navigate through certain features and user pages—that the participants proposed changes and made suggestions regarding the design of the eCARE-PD platform.

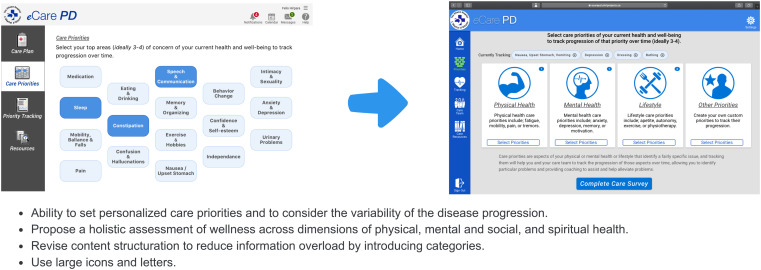

During the workshops, participants suggested changes to the user interface of the α prototype that was submitted to them but also made improvements on functionalities in order to make the eCARE-PD platform more meaningful and tailored to individuals’ needs. The suggested changes were integrated into the design of the β prototype (for an example see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Design implications (example from the α prototype to the β prototype).

Use & test: Six main issues after using the β prototype at home

The goal of the home testing period was to assess the platform itself, namely both its usability (practical acceptability) and its use and inclusion in activities of daily living (social acceptability). Stated otherwise, the goal was not only to identify technical problems or with the user-interface designs but also to consider the development of this technology in meaningful uses for PwPs. After the home test, several usage issues emerged that generated difficulties and dissatisfaction for those within the user group (Figure 4). The main problems are presented and illustrated with comments provided by the participants in the section below.

Figure 4.

Six main issues identified during the test at home.

Need to increase usefulness

One of the issues raised by the participants was related to what is called “usefulness,” that is, the perception they had of the benefits they could derive from using the platform daily. In general, users saw potential in the platform, but they pointed out issues that, at this time, do not commit them to long-term use. Several reasons are put forward, including an important one which concerns the fact that the platform is not engaging, because it does not support them in their process of identifying their health priorities and does not offer them the personalized support they expect. Specifically, they would like it to generate a personal action plan that is adapted to individual needs and realities. In other words, making the platform more useful means making it more customizable by including a feature that will help them set goals and encourage them to engage in activities and to stay motivated despite periods of discouragement.

It was interesting at first, but after a week it became obvious there was little change day to day and so was less motivating to complete. The platform is not very engaging. (Patient)

As currently designed, I probably would not be motivated to keep using it over long term. (Patient)

This platform has the potential to empower individual people with Parkinson's to have a role in “making things better.” Identifying priorities is only the first step. Some action will be required if you are going to see any change. That is why I think including a plan of action and/or goal-setting would make this a more effective tool. (Patient)

Lack of clear guidance

Another problem that was identified was that of support in the “guidance” of the platform. This refers to the means used in the platform's design to orient and guide users in its use. Users raised two central problems that generated confusion during the home test. A first problem concerns the lack of clear instructions on how to use the platform, as illustrated in the comment below.

Clear instructions should be added to the Home Page (as well as in several other places in the tool)—this will alleviate the frustrations that arise when things are not clear and participation in the use of the tool may be delayed, rejected, or wrongly executed. (Patient)

And the second problem relates to the lack of explanations to clearly introduce the purpose and goals of the platform. This second problem relates more to the purpose of the platform and its meaning for users, as the following excerpts illustrate.

I think the tool is a good start but is incomplete. With improved instructions, provision of a context (what it is, why use it, how use it, who should use it, a common understanding of what it means to “self-manage” and the addition of an action plan/goal-setting, I think it will be used more and provide greater satisfaction and reward. (Patient)

A clear understanding of what it means to “manage” your care priorities is necessary in order to use the tool effectively. (Patient)

The “guidance” problem also arose when using the tool to identify and select health priorities. Users were sometimes confused and interpreted this exercise in self-reflection on choosing one's health priorities very differently. For some, identifying only three or four priorities was unrealistic given their condition. For others, this exercise was useful and helped them focus on the issues of the day. Thus, the testimonies underline the equivocity 39 of this tool, which generated multiple interpretations on the part of users.

The tool suggests [the] ideal is 3–4 priorities. This seems pointless to me. In my experience I have a larger number of symptoms that vary in severity over time. (Patient)

I like the idea of setting some priorities to concentrate on at any one time. If one has a whole litany of things that are going wrong or are difficult, it can be overwhelming and impossible to focus on the improvement any of item. It helps to separate the issues and tackle them one or two at a time. (Patient)

Lack of interactivity and increase compatibility with disease progression

Another problem raised by users is the platform's lack of interactivity: they think it could be made more dynamic and interactive by promoting access to multimodal information or, in other words, by integrating text, images, and videos. Another aspect that was raised during the test is the capability of the platform to adapt to the characteristics of PwP users with motor problems, vision difficulties, or cognitive problems. Thus, compatibility problems were identified on several occasions. This raises an important issue in the design of a tool intended to be used by PwPs, namely its capacity to be a more “responsive” and inclusive technology, allowing it to be used by people who have motor, cognitive, or vision impairments.

Recall that PD is a progressive, degenerative disease affecting dexterity, mobility, as well as cognitive functions, so with time a patient is likely to have increasing difficulty to input/interface with the platform. These factors must be taken into account in the design of the platform. (Patient)

Recognizing that PD is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease, mobility and cognitive change must be taken into account in the interface of the platform. (Patient)

Consider needs of the person with Parkinson's who will be using it: tremors, dyskinesias, vision, slowness, often not intuitive/well-versed in the use of this technology. (Patient)

In summary, we need to adapt the platform to the progression of the disease for improving usability and making the technology more inclusive. Practical recommendation to limit these problems and improve the long-term use was done by the participants during the design process. These aspects were considered in the design of eCARE-PD since technological choices were made to consider the lack of usability when the disease progresses. For example, the use of eCARE-PD as an Internet-based app makes it more accessible. We incorporated some aspects of disease progression in eCARE-PD (e.g. larger font or icons, accessible to care partners) and other features can be done (e.g. voice-enabled features).

Improve collaborative use

In addition, some users have pointed out that this technology was designed for personal use whereas the management of PD is collaborative work that involves the care team, but also informal caregivers. This is a piece that should, for users, be taken into account in the design by offering, for example, resources for caregivers and not just for patients.

Start with co-management between the patient and their health professional using the platform to build a history and become familiar with the concepts and trends. Once co-management has stabilized, the patient could take increasing control. (Patient)

Increase personalization

An important and central aspect highlighted by users is that of “adaptability” and personalization. Users mention that they want to have a platform that is flexible and adapts to different use. Some patients, for example, will want to use it every day, and others will use it once a week or even once a month.

I found it hard to commit to a response on a daily basis. Once a week might be more realistic for some people. It may depend on the priority issue—some might benefit from daily input (e.g. constipation), some from weekly input. (Patient)

Daily entries are hard to maintain, especially as you’d have to do it near the end of each day when you might be tired, when you don’t want to be sitting in front of a screen, just before bedtime. (Patient)

It is important for users that the platform adapts to these different uses which would increase its social acceptability. In fact, patients use it for various reasons, such as documentary tracking to remember certain events to share with their care team; setting goals to be reached (goals tracking); and having access to personalized resources or getting help and support by receiving tailor-made advice (support tracking). Everyone therefore invests in this technology in different ways and makes use of it in ways that are meaningful to them.

It is like keeping a journal, as it relates to an important part of my life. I can see ways I can help myself by improving certain priorities. (Patient)

I like the fact that it acts like a journal, it keeps track of my symptoms. And looking back at it, I can see patterns of behavior and get help, information I need to take a better care of myself. (Patient)

It is essential for users that the platform offer them advice, suggest personalized programs, and recommend resources given their age, their symptoms, the stage of their disease, and their social needs. Several of them pointed out that the platform did not offer the expected degree of customization, and this could discourage and demotivate them from using it over the long term.

It does provide me with some useful information, but only in the early stage of the disease. What use is this page after five years living with PD. (Patient)

When entering data, a “tip” currently appears when the (face drawing) icon is selected. The tips should appear regardless of which icon is selected, or at least when one of the rightmost icons is selected. Email the results weekly with analysis and recommendations on how to improve. (Patient)

Once the Care Survey is completed, it ought to tell me automatically go to graph or tell me to go view results. (Patient)

Improve data visualization

One of the elements that has been the subject of several comments is the report generated following the use of the tracking tool. The graphics and visualizations generated by the platform are difficult to read and interpret. The graphics are confusing, and it is difficult for users to be able to use these results to make decisions. In summary, it is difficult to interpret the data generated by the platform and thus to give those data a social value and actionability, such as, for example, evaluating the impact of an exercise program on certain symptoms and making a commitment to continue with this program.

Meaningful tool to keep track on my symptoms, see a pattern. Especially by making an effort to comment/add notes on a daily basis. (Patient)

I would like to know that I can somehow influence that progress myself. I think incorporating a plan of action and/or set goals would help. E.g., for constipation, after reading the Facts and Tips sheet, I might want to try taking a full glass of hot water in the early morning, eat two prunes each day, increase my exercise activities, talk to my GP or neurologist at my regular appointment next week… (Patient)

The history function may reveal symptom progression and association with daily activities, implying a possible cause–effect relationship. […] The user should be able to see his/her comment when an icon is selected on the “Trends” plot. (Patient)

They also suggested reworking the user interface of these pages to make them more meaningful and less cluttered, for example, by allowing the user to filter information. In summary, during the home test participants evaluated the platform, but also made suggestions for changes in the design in order to address the usage problems they encountered. The home test therefore allowed us to assess both the practical and social acceptability of the technology and to raise several questions relating to the design of the eCARE-PD platform.

Final solution: design requirements and tailoring strategies proposed by the participants

Three main design requirements for improving eCARE-PD

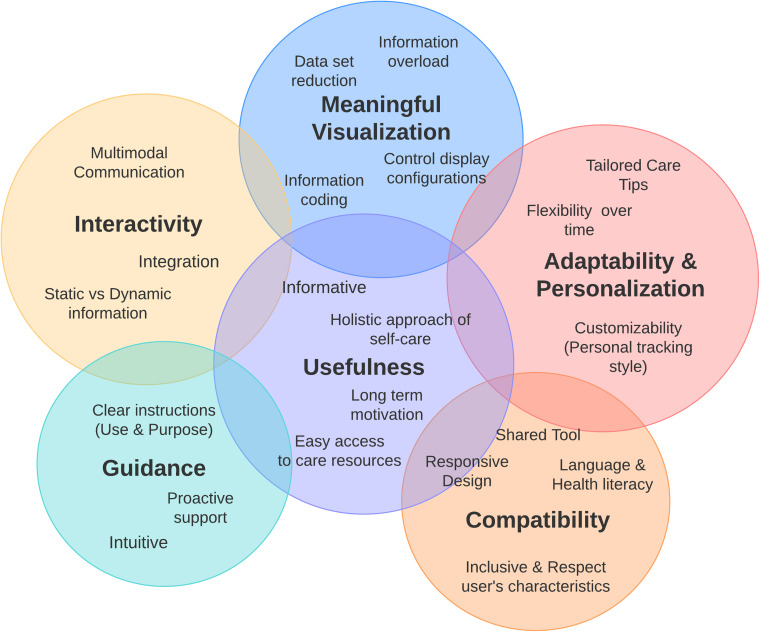

The remote co-design workshops with PwPs and design critique sessions allowed us to identify three design requirements aimed at improving the platform (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Three key design requirements for improving eCARE-PD.

First, the eCARE-PD platform had to be made more meaningful to users, especially in order to increase its usefulness—in other words, a platform that offers them support in managing their health priorities at home and helps them maintain a QoL. To do this, it must not only meet their medical needs (e.g. information on the disease, treatments), but also be part of a holistic approach to managing the disease, take into account their well-being and social needs (e.g. provide access to resources within the community and offer practical advice to help them sustain a social life), and be integrated in their existing self-care practices by making possible different forms of use. Very concrete solutions have therefore been suggested in terms of design. For example, it is important that eCARE-PD integrate not only medical but also non-medical resources, such as practical advice for adapting one's home when certain symptoms worsen and advice for continuing to have an active social life. Another proposed solution was for the platform to help them and accompany them—via questions asked or a tutorial they can access upon request—in the process of self-reflection regarding the identification of their health priorities (increase guidance).

It was also suggested that the platform be made more human and warm, in particular to increase its adaptability and acceptability. PwPs describe their relationship with technology not as purely functional, but also as social and emotional. They therefore suggest that this platform be made more human and warm so it can play the role of the expected digital companion. Even though eCARE-PD is seen as a useful and functional tool, it lacks humanity and users suggest making the relationship and their interaction with it more positive. Two solutions are proposed: (a) adopt a positive and empathetic tone on the platform; (b) focus on realistic and positive actions that can help users achieve their goals. Thus, it is the language of technology that must be reviewed (e.g. the words and icons used), the way in which goals are presented and formulated (e.g. emphasizing the goals; actions to be implemented). They suggest also making it more human and engaging by promoting access to multimodal information (e.g. videos, texts, images, computer graphics, podcasts). We also know that different media formats are particularly relevant for people with low health literacy, the elderly, or with cognitive problems, because it reduces the cognitive load. 40

And finally, it is essential that the platform be made more interactive and personalized—that is, that it be designed as an inclusive platform that adapts to the physical and cognitive limitations that users may have. That is, an engaging platform that offers resources in different formats (texts, videos, infographics), but also a personalized platform able to generate tailored care tips and offer users relevant resources adapted to their needs (educational and community resources). The idea, thus, would be to have a platform that offers a personalized and realistic action plan depending on the stage of the disease and/or the patient's age and to support patients on a daily basis by offering them educational resources and helping them navigate the resources available in their community.

A combination of two tailoring strategies for designing a personalized eHealth platform

The goal of this technology is to provide patients with personalized health information and advice that evolve over time and meet their current needs. One of the recurring issues raised by participants during the co-design process was the level of personalization of care tips and other resources. During the design critique sessions, this question was widely discussed, because personalization is at the heart of the care offerings that can be provided as part of an integrated care model. It was therefore fundamental to integrate it into the platform, as much for patients as for their informal caregivers as well as for professional healthcare providers.

During the design critique sessions, participants suggested that eCARE-PD include two types of personalized the content which the platform might generate: adaptive and adaptable content, as these excerpts illustrate.

If we want to make it more attractive to patients and engage patients right now, all the care tips are individualized so why can't we have patients select the one they want; we just offer them one by one and say like, for example, have you tried this? Or do you want to try this? And if they say “yes,” then you stick with that care tip until they are happy, or they are not… (Health Care Providers)

Why can't we, on the same day, then present another one, and if the patient says “yes,” it becomes the care tip until either things are not still going well or he says I've done it, I want more, and the process [starts] again. A little bit of tailoring and in a way, it avoids the how can we customize automatically these for the patients. (Health Care Providers)

Adaptive content, which generates tailored care tips, is triggered by the system once the user has completed the questionnaire found in the tracking tool. This content is then generated automatically based on a patient's responses to the questionnaire. As the design process progressed, however, it became clear that a single, adaptive content was not enough to personalize eCARE-PD. The proposed solution was therefore to add adaptable content to allow patients to modify what the system generated to better meet their needs. This is why it was suggested that the platform be designed to include adaptable customization driven by user feedback. Patients can choose to reject or add to their personal action plan the “care tips” generated by the platform, and thus, ask the platform to generate another care tip. This way of personalizing content, as can be found in some recommender systems, is thus based on user feedback.

For eCARE-PD, the recommender system could generate three types of recommendations: (1) tailored care tips (based on self-tracking, triggers, trends, and user feedback); (2) customizable educational and community resources (based on user preferences, profiles, and geolocations); and (3) personalized care resources (based on generated care tips and patient profiles).

For the participants, the personalization work the platform carries out has three objectives: (1) adapt the content of personalized messages (care tips) to the information needs of users; (2) link and frame the content of personalized messages (care tips) and resources to the user's current situation (e.g. health priorities identified and tracked); and (3) offer personalized advice in a format that is accessible, interactive, and dynamic. The results therefore underscore the value of developing a technology that offers personalized and flexible support—in other words, a platform that is adaptable and that evolves according to a patient's trajectory and priorities at a given time. eCARE-PD is therefore designed to offer personalized and continuous support throughout a patient's trajectory, that is to say to be a tailored technology based in particular on a recommender system.

Discussion

Using a co-design approach involving PwPs, their informal caregivers, and healthcare providers, our study sought to identify the functionalities that needed to be integrated into healthcare technology in order to support patients in their self-care process at home. In other words, this technology had to be a resource in an integrated care model for PwPs by supporting them and guiding them in their daily self-care.

Our study reveals that what is at the heart of the design of such an eHealth tool is customizing the platform—an issue that has been at the center of discussions throughout this project's various co-design cycles and which is an important element in making the platform acceptable and useful for users. Moreover, it is by increasing the degree of personalization that PwPs will be more inclined to use it over the long term. The long-term use of such eHealth platforms is a major issue, and the work carried out in recent years underlines a significant attrition rate in the use of these self-management technologies.41,42 In this context, the point is to take into account different use when designing this platform. Indeed, patients will use eCARE-PD for various reasons; to document symptoms (documentary tracking), for example, or to set goals of care (goals tracking). It is by integrating different use that this platform will be socially acceptable and that users will be able to conceive of using it long term. Indeed, uses can change over time depending on patients’ needs and expectations, depending on the course of their disease. Thus, by favoring a holistic approach and incorporating it into the platform design, we allow these different use configurations to be made possible.

During our study, the challenge of personalizing the eCARE-PD platform manifested in three ways: (a) in its ability to support a holistic approach to the disease and to register in different configurations of use; (b) in its ability to produce meaningful visualizations and to improve the social value of shared data; and finally (c) in its ability to improve the work of personalizing recommendations by generating advice and tailor-made health messages. Consequently, our study shows that what makes this technology meaningful for users is:

on the one hand, its ability to fit different use, to adapt to user needs by supporting them in the course of their care, and by sending them personalized advice;

and, on the other hand, the fact that it incorporates a holistic approach to the disease, taking into account general a PwP's well-being and medical and social needs.

This led us to integrate three complementary functionalities into the design in order to design a personalized eHealth platform supporting self-care: (1) preparation, self-representation, and a self-tracking tool; (2) a personal report and meaningful visualizations; and (3) tailored care recommendations and customizable care resources. These three functionalities make it possible to support the three stages of the self-care process as defined by Cornet et al. 15 : monitoring, interpretation, and action.

Functionality 1: preparation, self-representation, and a self-tracking tool (monitoring)

In the monitoring preparation phase, the health priority selection tool plays a central role because it will allow PwPs to configure the tool to meet their needs. However, the co-design process revealed that users needed to be guided and supported in this key step. The tool that was initially proposed was not intuitive, and its purpose lacked clarity. In short, for this tool to make sense to users, it had to be of meaningful use to them by encouraging them to reflect on their current priorities. The idea was also that the tool should not only focus on symptoms and problems; indeed some users emphasized the coldness of the platform which transmitted a negative image of the future. 43 This aspect of the acceptability of technology is fundamental, because one can see the negative effect that technology can have on self-image. And, in the context of Parkinson's disease, it is fundamental to consider this in the design. Thus, during the design critique sessions, participants suggested solutions to make the platform more positive, warm, and helpful, in order to encourage them to focus their attention on their current goals and objectives, which evolve over time.

Functionality 2: personal report and meaningful visualizations (interpretation)

Moreover, technology becomes meaningful if the data it produces are meaningful to users. Thus, graphics and visualizations should support PwPs in their capacity to maintain “meaningful reflection,” in particular by allowing them to manage, explore, and interpret the data generated by this technology. 17 The term “personal informatics” is used in the literature to describe those systems that help people identify, select, and track health data that are useful to them and that will support a process of self-reflection and learning. 41 Participants therefore made concrete suggestions to improve the visualization of the data and make the graphs more readable and interpretable.

As a result, one of the contributions of our study is to reveal the importance of data visualization in designing technologies to support the process of self-care. Indeed, it is about designing and developing technologies based on self-tracking tools to allow users to visualize trends or to measure the effect of their self-care efforts on what they have identified as their current priorities. For example: Did tips for dealing with “freezing” episodes at home have an impact on anxiety levels? eCARE-PD will therefore have to produce graphs that are easily interpretable, and which make monitored data meaningful to users. Making them meaningful also means that they will be of value to users. This is what some researchers call “data valences,”44,45 a concept that emphasizes the different expectations and values that data may have depending on the context of their use. In our case, these differences are expressed at two levels: (a) their meaningful use, (b) their “actionability” (e.g. which data can help to make action-decisions or support communications between patient and provider during clinical follow-ups). The data generated by the platform should be considered of value to users if it is readable, easily interpreted, and personalized. 46 The point is to make the data understandable, favor graphics and visualizations that are simple and customizable, by allowing users to filter the data according to their needs. The issue of data visualization is therefore an issue that should not be overlooked, especially in the design of technologies aimed at supporting self-care practices. In addition, the ability for a tool to generate personalized and meaningful data for users has an impact on motivation and engagement.47,48

Access to personalized data presented in an easily interpretable format has the potential to support longer-term use of these technologies.49,50 In addition, our study reveals that users express the need to have access to charts that highlight trends, but also to have reports that are connected to the recommendations they receive. For this, the platform must have different forms of data visualizations: personalized summaries of a patient's data collected over a week; graphic representations presenting the evolution of that data over several months; but also, narrative forms of data presentation as they provide personalized suggestions. In this respect, making the self-tracking experience engaging also involves some thought about how to present the data that the system collects and generates. 51

Functionality 3: tailored care recommendations and customizable educational and community resources (action)

As our results show, what makes the platform attractive and engaging for users is its ability to offer personalized health advice that is tailored to each patient's needs and expectations. The customizing work, however, that the platform is currently accomplishing is unsatisfactory for several reasons that were presented above. On the one hand, users feel that messages are addressed only to a single patient category (e.g. newly diagnosed patients) and on the other that messages are poorly adapted to the realities of patients who have been living with the disease for several years. Personalization, however, is an essential element of the platform in order to maintain its use over the long term.

Our findings show that both tailoring strategies, namely system-driven tailoring (personalization) and user-driven tailoring (customization), ought to be integrated in the development of a tailored digital health technology tool designed to support self-care at home. The first strategy is based on the personalization of recommendations by the system itself—in other words, a system-driven way of delivering care tips or health information in a pre-planned format, based on an assessment of individual care priorities. The system tracks users’ care priorities and then provides information that matches their identified and assessed care priorities. With eCARE-PD, an automatic personalization system collects data directly from the user (e.g. by asking users to identify their care priorities) and tracks user care priorities (e.g. in the self-tracking tool). The second strategy, “customization,” is based on a user-driven approach. In this case, users are asked to customize the content of the messages presented to them either by giving their feedback or by asking them to choose from suggested content. Recent studies have shown that customization and perceived active control over health information can improve health messages effectiveness.52,53 Customization induces a sense of agency and involvement with information content, which results in a positive attitude toward the conveyed information. 54

Although this is discussed little when designing and developing technologies for PwPs, our study underscores the importance of developing systems that are able to offer personalized recommendations to users. Wannheden and Revenäs 8 also found this in a study of the development of an eHealth technological platform to support co-care. PwPs also expressed the need to receive tailored recommendations for self-care. They stress, however, that these recommender systems are still underdeveloped even though “personalized recommendations was considered essential to support individual needs-based health care and self-care.” 8 Nevertheless, these recommender systems are ubiquitous in many aspects of life today, including e-commerce, entertainment, and social media, but still not very present in the field of health technologies. And still, recent literature has highlighted an opportunity for digital health technologies to use personalization to increase the persuasive influence of a system and encourage behavioral changes.55,56 Few studies, however, suggest developing personalized systems to encourage and support health self-management which are not limited to simple behavioral changes. What PwPs do expect is a technological tool that offers them the capability to set realistic goals and overcome their personal health management challenges, using a system of friendly and warm recommendations. And it is, moreover, recognized in the literature that tailored health messages are digital communication strategies that are more motivating and engaging for people when it comes to health promotion, patient education, and supporting changes in habits. 57

Conclusions

In summary, one of the contributions of our study is to show that the design of a tailored digital health technology supporting self-care is based on three complementary functionalities: (a) preparation, “self-representation” about care priorities, and self-tracking; (b) personal reports and meaningful visualizations; and (c) tailored care recommendations based on system-driven and user-driven tailoring (e.g. adaptative and adaptable content). Developing more sophisticated personalized eHealth platforms for PwP able to build recommender systems that support individualized self-care for each PwP is warranted. A recommender system seeks to predict if a care tip would be useful to a user based on given information (such as socio-demographic data, medical assessment, self-assessment of care priorities, trends, etc.). The use of Artificial Intelligence–based systems may support such tailored development of eHealth technologies that are deemed to become key components of integrated care networks. But more research is needed to identify which recommender system would be most valuable and effective.

Our study opens up avenues for reflection on the design and development of eHealth technologies supporting self-care that is based in particular on the system's capacity to generate tailor-made advice and resources. In our opinion, this is an important stake in these types of technologies, if one considers both their long-term use but also integrating them into an integrated care model. Indeed, in an integrated care model, the issue of personalization is central, and it is important to think about how to design flexible, customizable technologies that suit multiple use configurations. This challenge requires more research, including considering how technological developments based on learning algorithms and artificial intelligence could help achieve this goal. Despite technological advances in the development of self-care and self-management platforms, there remain the challenges of both the practical and social acceptability of such systems, which are directly linked to their ability to meet the requirements of customizing recommendations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank participants for their time and contribution in this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributorship: SG, DG, TM, DC participated in the study concept and design. SG, EP, AGP collected the data. SG, JLC, EP participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. SG drafted the manuscript, and JLC, AGP, TM, EP critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board (Protocol # 20180561-01H).

Funding: This is an EU Joint Programme - Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project. (Reference number: HESOCARE-329-073) The project is supported through the following funding organisation under the aegis of JPND - www.jpnd.eu (Canadian Institutes for Health Research - CIHR).

Guarantor: SG.

ORCID iD: Sylvie Grosjean https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4568-0500

References

- 1.Dorsey ER, Vlaanderen FP, Engelen LJet al. et al. Moving Parkinson care to the home. Mov Disord 2016; 31: 1258–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SY, Tan AH, Fox SHet al. et al. Integrating patient concerns into Parkinson's disease management. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017; 17: 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellqvist C, Dizdar N, Hagell Pet al. et al. Improving self–management for persons with Parkinson's Disease through education focusing on management of daily life: patients’ and relatives’ experience of the Swedish National Parkinson school. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 3719–3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tenison E, Henderson EJ. Multimorbidity and frailty: tackling complexity in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinson's Disease Preprint 2020; 10: S85–S91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes F, Silva P, Cevada Jet al. et al. User interface design guidelines for smartphone applications for people with Parkinson’s disease. Univ Access Inf Soc 2015; 15: 659–679. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lluch M, Abadie F. Exploring the role of ICT in the provision of integrated care—evidence from eight countries. Health Policy 2013; 111: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luis-Martínez R, Monje MH, Antonini A, Sánchez-Ferro Á and Mestre TA. Technology-enabled care: Integrating multidisciplinary care in Parkinson's disease through digital technology. Front Neurol 2020; 11. 10.3389/fneur.2020.575975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wannheden C, Revenäs Å. How people with Parkinson's disease and health care professionals wish to partner in care using eHealth: co-design study. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e19195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linares-Del Rey M, Vela-Desojo L, Cano-de la Cuerda R. Mobile phone applications in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Neurología (English Edition) 2019; 34: 38–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espay AJ, Hausdorff JM, Sánchez-Ferro Áet al. et al. Movement disorder society task force on technology. A roadmap for implementation of patient-centered digital outcome measures in Parkinson's disease obtained using mobile health technologies. Mov Disord 2019; 34: 657–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lima AL S, Smits T, Darweesh SKLet al. Home-based monitoring of falls using wearable sensors in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2020; 35: 109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan D, Dhall R, Lieberman Aet al. et al. A mobile cloud-based Parkinson’s disease assessment system for home-based monitoring. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015; 3: e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakshminarayana R, Wang D, Burn D, et al. Using a smartphone- based self-management platform to support medication adherence and clinical consultation in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2017; 9: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Son H, Park WS, Kim H. Mobility monitoring using smart technologies for Parkinson’s disease in free-living environment. Collegian 2018; 25: 549–560. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornet VP, Daley C, Cavalcanti LHet al. et al. Design for self-care. In: Design for health. xx: Academic Press, 2020, pp.277–302. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Halteren AD, Munneke M, Smit Eet al. et al. Personalized care management for persons with Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2020; 10: S11–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li I, Dey AK, Forlizzi J. Understanding My Data, Myself: Supporting Self-reflection with Ubicomp Technologies. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp ‘11), 2011; 405– 414. New York, NY: ACM.

- 18.Riggare S, Stamford J, Hägglund M. A long way to go: patient perspectives on digital health for Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2021; 11: S5–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva de Lima AL, Hahn T, Evers LJet al. et al. Feasibility of large-scale deployment of multiple wearable sensors in Parkinson's disease. PloS one 2017; 12: e0189161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunes F, Fitzpatrick G. Self-Care technologies and collaboration. Int J Hum Comput Interact 2015; 30): 869–881. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjerkan J, Hedlund M, Hellesø R. Patients’ contribution to the development of a web-based plan for integrated care – a participatory design study. Inf Health Social Care 2015; 40: 167–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bol N, Smit ES, Lustria MLA. Tailored health communication: opportunities and challenges in the digital era. Digit Health 2020; 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207620958913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kessler D, Hauteclocque J, Grimes D, Mestre T, Côtá D and Liddy C. Development of the integrated Parkinson's care network (IPCN): using co-design to plan collaborative care for people with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 2019; 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Simonsen J, Robertson T. Routledge international handbook of participatory design. New York: Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen S, McSeveny K, Lockley Eet al. et al. How was it for you? Experiences of participatory design in the UK health service. CoDesign: Int J CoCreation Des Arts 2013; 9: 230–246. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregory J. Scandinavian approaches to participatory design. Int J Eng Educ 2003; 19: 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Velden M, Mörtberg C. Participatory design and design for values. In: van den Hoven J, Vermaas P, van de Poel I. (eds) Handbook of ethics, values, and technological design. (pp. 215–236) Dordrecht: Springer, 2015. 10.1007/978-94-007-6970-0_33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders EBN, Stappers PJ. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-design 2008; 4: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen J. Usability engineering. Boston: Academic Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]