Abstract

Avian colibacillosis is a serious systemic infectious disease in poultry and caused by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Previous studies have shown that 2-component systems (TCSs) are involved in the pathogenicity of APEC. OmpR, a response regulator of OmpR/EnvZ TCS, plays an important role in E. coli K-12. However, whether OmpR correlates with APEC pathogenesis has not been established. In this study, we constructed an ompR gene mutant and complement strains by using the CRISPR-Cas9 system and found that the inactivation of the ompR gene attenuated bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and the production of curli. The resistance to environmental stress, serum sensitivity, adhesion, and invasion of DF-1 cells, and pathogenicity in chicks were all significantly reduced in the mutant strain AE17ΔompR. These phenotypes were restored in the complement strain AE17C-ompR. The qRT-PCR results showed that OmpR influences the expression of genes associated with the flagellum, biofilm formation, and virulence. These findings indicate that the regulator OmpR contributes to APEC pathogenicity by affecting the expression and function of virulence factors.

Key words: avian pathogenic Escherichia coli, response regulator, OmpR, pathogenicity

INTRODUCTION

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) is a typical extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) that is mainly transmitted through the respiratory tract. It causes serious localized or systemic infectious diseases in poultry and significant economic losses in the poultry industry (Nakazato et al., 2009). APEC contaminates poultry meat or eggs, to cause human extraintestinal disease (Ramírez et al., 2009). Furthermore, APEC and human ExPEC share some virulence genes, suggesting that APEC is a reservoir of ExPEC virulence genes (Chanteloup et al., 2011; Griffin et al., 2012; Mellata, 2013). APEC has numerous virulence factors, such as 2-component systems (TCSs), quorum sensing (QS), and a secretion system, which are closely related to the pathogenicity and drug resistance of bacteria (Nakazato et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2017). The pathogenic mechanism of APEC is complex. Therefore, it is important to investigate the pathogenic mechanisms of APEC to increase control in poultry farming and public health safety.

Comparative genomic analysis indicates that about 62 TCSs genes are conserved in E. coli genomes, these include BarA/UvrY, PhoP/Q, KdpD/E, CpxR/A, BasS/R, OmpR/EnvZ, etc (Capra and Laub, 2012). In APEC, the function of some TCSs has been identified and they are involved in bacterial growth, biofilm formation, response to environmental stress, drug resistance, and pathogenicity. The BasS/R inhibits biofilm formation, colonization in chickens, and virulence of APEC (Yu et al., 2020). The CpxR/A system regulates the motility, biofilm, and production of type Ⅰ fimbriae of APEC (Matter et al., 2018). The RstA/B TCS participates in the pathogenicity of APEC and adapts to survival under stress (Gao et al., 2015). Previous studies have shown that PhoP/Q significantly reduces invasion and adhesion to primary chicken embryonic fibroblasts (CEF) cells and virulence (Tu et al., 2016) and KdpD/E influences flagellum formation, motility, and serum to resistance (Xue et al., 2020a). Therefore, studying the role of the TCS in APEC is conducive to elucidating the pathogenic regulatory mechanism of APEC, which is of great significance for the prevention and treatment of colibacillosis.

The OmpR/EnvZ TCS is a global regulation system and plays an important role in mediating signal transduction in response to environmental osmotic pressure in Gram-negative bacteria (Capra and Laub, 2012; Quinn et al., 2014). The OmpR/EnvZ consists of a histidine kinase EnvZ and a cytoplasmic response regulator OmpR (Cai and Inouye, 2002). The transcription factor OmpR directly binds to the outer membrane protein genes ompF and ompC. In response to osmotic stress, OmpC is expressed preferentially at high osmolarity and OmpF is expressed preferentially at low osmolarity (Cai and Inouye, 2002; Foo et al., 2015). In E. coli K-12, the transcriptional regulator OmpR also regulates the virulence-associated genes flhD, flhC, fimB, and csgD (Jubelin et al., 2005; Rentschler et al., 2013; Samanta et al., 2013). OmpR contributes to the pathogenesis of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), and OmpR can directly bind to ler and stx1(Wang et al., 2021). In adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), OmpR is essential for adhesion and invasion of intestinal epithelial cells and colonization of the mouse gut (Rolhion et al., 2007; Lucchini et al., 2021). OmpR regulates the expression of the SPI-2 type III secretion system and 2-component system SsrA/B in Salmonella (Lee et al., 2000; Feng et al., 2003; Cameron and Dorman, 2012). In Yersinia enterocolitica, OmpR is a regulator that controls the expression of genes involved in cellular processes and virulence (Reboul et al., 2014). OmpR also inhibits the expression of porin kdgM2 and enhances adaptability to the environment (Nieckarz et al., 2016). In Burkholderia, ompR leads to reduced antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence (Cooper, 2018). However, the roles of OmpR/EnvZ in regulating the pathogenesis of APEC have not been reported.

In this study, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was used to construct an ompR gene mutant strain. We found that the regulator ompR mainly affected flagella formation, motility, biofilm formation, response to environmental stress, serum resistance, and virulence in the APEC of infected chickens, and also affected the expression of virulence genes. These results indicated that the regulator OmpR positively regulates the pathogenicity of APEC. Thus, these findings will contribute to our understanding of the function of the TCS, clarify the pathogenic mechanism in APEC, and provide potential drug targets for the treatment and prevention of APEC infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

APEC17 (serotype O2) was isolated from a case of avian colibacillosis in Anhui Province, China (Tu et al., 2016). Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. When necessary, LB medium was supplemented with ampicillin (Amp, 100 µg/mL), spectinomycin (Spec, 100 µg/mL), kanamycin (Kan, 50 µg/mL), and chloramphenicol (Cm, 30 µg/mL).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| AE17 | APEC wild-type strain | Laboratory stock |

| AE17ΔompR | AE17 ompR deletion mutant | This study |

| AE17C-ompR | AE17 ompR with the complement plasmid pCm-ompR, Cmr | This study |

| DH5α | lacZ∆M15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTargetF | High copy cloning vector, pMB1 aadA sgRNA-cat, Specr | Addgene |

| pCas | Low copy cloning vector, temperature sensitive, Pcas-cas9 ParaB-Red lacIq Ptrc-sgRNA-pMB1, Kanr | Addgene |

| pSTV28 | Low copy cloning vector, p15A origin, Cmr | Takara |

| pCm-ompR | pSTV28 with ompR gene, Cmr | This study |

Abbreviations: Cmr, chloramphenicol-resistant; Kanr, kanamycin-resistant; Specr, Spectinomycin Hydrochloride-resistant.

Construction of Mutant Strain AE17ΔompR

The mutant strain AE17ΔompR was constructed by using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. The nuclease Cas protein 9 (Cas9) and synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) are co-transferred to target cells to induce expression of sgRNA and Cas9 protein to form crRNP complexes that recognize and direct Cas9 protein to act on genomic targets to produce DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs). The target genes are edited through homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) DNA repair (Jiang et al., 2015b; Chung et al., 2017). The primers used are listed in Table 2. Briefly, the ompR upstream (ompR-L) and downstream (ompR-R) frames were amplified by PCR with primers ompR-L-F/R and ompR-R-F/R (containing Hind III digest site) from AE17 genomic DNA, respectively. The ompR-sgRNA frame was amplified with the primers ompR-sgRNA-F/R (containing Spe I digest site) from the plasmid pTargetF. The overlap method was used to combine the 3 fragments into the ompR-sgRNA+L+R large fragment. The large fragment and pTargetF plasmid were digested with Hind III and Spe I, respectively, and transformed into E. coli DH5α by chemical transformation (ice-bath for 30 min, 42°C for 90 s, and ice-bath for 2 min). The transformed E. coli DH5α were then spread on LB agar (with Spec) and identified with primers pTargetF-F/R to construct the recombinant plasmid pTargetF-ompR.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5'-3') | Product size/bp |

|---|---|---|

| AE17-F | GAGCGATCTTGGCTATACC | 1,023 |

| AE17-R | GTGAAGCTATCTAACAACGG | |

| ompR-L-F | TTTTTTTGAGGCGTTGCA CTCTTCGATATCTTT | 832 |

| ompR-L-R | AGTATAAACAGGCGATTGC GCTTCTCGC | |

| ompR-R-F | CGCAATCGCCTGTTTATACTCC CAAAGGTTCG | 852 |

| ompR-R-R | CCAAGCTTTGCGGCAGAA CGAATCAT | |

| ompR-sgRNA-F | AATACTAGTTGAATGTAACGCGGATGCGCGTTTT AGAGCTAGAAATAGC | 3,320 |

| ompR-sgRNA-R | AGTGCAACGCCTCAAAAAAAGC ACCGACTCGG | |

| ompR-in-F | TTCTGGTGGTCGAT GACGATATG | 493 |

| ompR-in-R | GCCTTCAGTACCGCAAA CTCAC | |

| ompR-out-F | CCTCAATGCTACCGGGGT | 2,681 |

| ompR-out-R | ACGCGTTTCCAGATTACGC | |

| ompR-BamHⅠ-F | CGCGGATCCATGCAAGAGAACTA CAAGAT | 720 |

| ompR-HindⅢ-R | CCCAAGCTTTCATGCTTTAGAACC GTCCG | |

| pTargetF-F | AGCGAGGAAGCGGAAGA GCG | 800 |

| pTargetF-R | CAAGATAGCCAGATCAATGT | |

| pCas-F | GTAACATCAGAGATTTTGAGA CAC | 4,714 |

| pCas-R | GATGTAGCCGTCAA GTTGTCA | |

| pSTV28-F | TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | 109 |

| pSTV28-R | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACC |

Restriction sites are underlined.

The AE17 was grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6, ice-bath for 30 min, centrifuged at 5,000 × g, and washed twice with 10% glycerol water. The plasmid pCas was extracted and transformed into AE17 competent cells by electroporation (200 Ω, 2,500 V) using a Gene Pulser MX cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), spread on LB plates (with Kan), and identified with primers pCas-F/R. Then the AE17-pCas was grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of approximately 0.2. At this stage, 30 µg/mL of arabinose was added and cultures were continued to an OD600 of 0.6. The recombinant plasmid pTargetF-ompR was transformed into AE17-pCas by electroporation and grown in LB (with Spec and Kan). Then, the strain was cultured in LB liquid medium (with Kan and 0.5 mM IPTG) to remove the pTargetF. The primers ompR-out-F/R and ompR-in-F/R were used to identify the mutant strain AE17ΔompR.

Construction of Complement Strain AE17C-ompR

We used AE17 as a template to amplify ompR fragment with primers ompR-BamH Ⅰ-F/ompR-Hind Ⅲ-R. Hind III and BamH I were used to digest the ompR fragment and plasmid pSTV28, respectively, and transformed into E. coli DH5α cells. The transformed E. coli DH5α cells were plated on LB plates (with Cm). The complement plasmid pSTV28-ompR was transformed into the AE17ΔompR competent cells by electroporation. The primers ompR-in-F/R were used to identify the complement strain AE17C-ompR.

Growth Curves, Motility, and Curli Assays

To determine the effect of the ompR gene on bacterial growth, the AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were determined on LB medium. Briefly, bacteria were incubated in LB medium at 37°C and 150 RPM, and the optical density (OD) of strains was monitored at 1 h intervals by spectrophotometry (Bio-Rad).

Overnight cultures of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were diluted 1:25 and statically cultured to the logarithmic phase. The bacteria were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), plated on the LB semi-solid medium (0.25% agar), and incubated at 37°C for 8 h, then the motile cycles of the strains were observed. The LB semi-solid medium was prepared from 0.5% NaCl, 1% tryptone, 0.8% glucose, and 0.25% agar powder (Sangon, Shanghai, China).

Congo red plates were used to detect curli production. The overnight bacteria were added to Congo red plates and incubated at 37°C for 3 d. Congo red plates were LB agar plate without salt supplemented with 40 mg/L Congo red (Sangon) and 20 mg/L brilliant blue (Sangon).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The bacterial flagella of the AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The strains were cultured to a logarithmic phase and washed with PBS 3 times. The bacteria were placed on a 200 mesh Formvar-coated copper microscopy grid and stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid. After drying, the bacterial micromorphology was observed by the electron microscope (Hitachi HT-7700, Tokyo, Japan).

Biofilm Formation Assay and Scanning Electron Microscopy

The biofilm was determined using a crystal violet (CV) assay as described previously (Yu et al., 2020). Briefly, the AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were cultured to logarithmic growth phase, the strains were diluted to an OD600 of approximately 0.03, and added to a sterile 96-well plate at 28°C for 48 h. Then, stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet (Sangon) for 20 min, and washed three times with PBS. Finally, 33% glacial acetic acid (Sangon) was added for 10 min. The OD492 of strains was monitored by using a microplate reader.

Cultures were added to a sterile 12-well plate, placed in a coverslip, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. First, the coverslip was washed with PBS. Next, 2.5% glutaraldehyde was added at 4°C for 8 h and washed three times with PBS. Then, the coverslip was serially placed in ethanol absolute at concentrations of 30, 50, 70, 80, 95, and 100%. Finally, the coverslip was transferred to acetone, vacuum freeze-dried, and observed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Hitachi S-4800).

Serum Bactericidal Assay

The determination of the survival ability of the bacteria in the serum was as described previously (Wang et al., 2015). Briefly, the AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were cultured to the logarithmic growth phase, centrifuged, and washed with PBS. Specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chicken serum (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was diluted with PBS to 25, 50, 75, or 100%. The heat-inactivated serum (at 56°C for 30 min) was used as a negative control. Bacteria incubated with different concentrations of serum were cultured at 37°C for 30 min. The number of surviving bacteria was counted by plating on LB agar plates.

Bacterial Resistance to Environmental Stress Assay

The survival ability of bacteria in diverse environmental stress was performed as described previously (Huang et al., 2009). Briefly, the AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were grown to logarithmic phase, centrifuged at 5,000 × g, and washed twice with PBS. In the acid assay, bacteria were cultured in LB medium (PH = 3) at 37°C for 30 min. In the alkali assay, bacteria were incubated in 100 μL Tris-HCl (100 mmol/L, pH 10.0) at 37°C for 30 min. In the osmotic pressure assay, the bacteria were incubated in NaCl (4.8 mol/L) at 37°C for 60 min. In the oxidative stress assay, the bacteria were incubated in 10 μM hydrogen peroxide at 37°C for 60 min. All experiments were repeated 3 times. The counts of surviving bacteria were calculated after plating on LB agar plates.

Bacterial Adherence and Invasion Assays

The bacterial adherence and invasion assay were performed as described previously (Song et al., 2018). Briefly, the AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were grown to the logarithmic phase and resuspended with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Biological Industries, Israel). Chicken embryo fibroblast (DF-1) cells were incubated with bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 CFU per at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1.5 h. After washing with PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria, cells were lysed with 0.5% TritonX-100, and the counts of adherent bacteria were calculated on LB agar plates.

For the invasion assay, the bacterial infection of cells was performed according to the adhesion assay. After 1.5 h of incubation, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended with DMEM containing gentamicin (100 µg/mL) for 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria. Then, the cells were washed and lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100, and the lysate was diluted in a 10-fold gradient to count invading bacteria on LB agar plates.

Animal Infection

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines of Anhui Agricultural University (Number: 2020-021) were followed in the management of these chicks. One-day-old chicks were purchased from Anhui Anqin Poultry Company Ltd. (Anhui Province, Hefei, China). The chicks can freely eat food and drink water. The chicks were euthanized by injecting intravenous sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) into the wing vein. An animal infection experiment was performed to determine the virulence of AE17 and AE17ΔompR strains in chickens. After a week of feeding, chicks were injected intramuscularly with 106 CFUs of each bacterial strain (Tu et al., 2016; Song et al., 2018). Negative controls were injected with PBS. The survival and death of the chicks were observed every day for a total of 7 d, and a survival curve was drawn to compare the virulence of these strains.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real‑Time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments were performed to examine the transcript levels of genes. The primers are listed in Table 3. Briefly, bacterial total RNA was isolated using Total RNA Extractor (Trizol; Sangon). The synthesis of cDNA was performed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa). Relative gene expression was normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene dnaE using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Table 3.

qRT-PCR primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Product size/bp |

|---|---|---|

| dnaE-F | GATTGAGCGTTATG TCGGAGGC | 92 |

| dnaE-R | GCCCCGCAGCCGTGAT | |

| cheY-F | TCCAGTCGGAGATAACA AATCCA | 119 |

| cheY-R | CATAGTGCGTAACCTGCTG AAAGA | |

| fimF-F | CGACGACTCCTGTTGTT CCATTT | 118 |

| fimF-R | AGTGCAAGCAGGTTG GCATTGTG | |

| fimG-F | ACGATCACGGTGAACGGTAAG | 107 |

| fimG-R | CCGGCAGACATAAGACT GAAAGA | |

| csgD-F | ATCGCCTGAGGTTATCGTTTG | 126 |

| csgD-R | AGATCGCTCGTTCGTTGTTCA | |

| ompA-F | CAGATCGTCAGTGATTGGGTAA | 120 |

| ompA-R | GAAATGGGTTATGACT GGTTAGG | |

| tolC-F | CACTTACCGACTCTGGA TTTGAC | 112 |

| tolC-R | GGCCCATATTGCTATCGTCAT | |

| fimH-F | CAGCGATGATTTCCAGTTTGT | 136 |

| fimH-R | AAGAGGAATCGGCACTGAACC | |

| mcbR-F | CTGTTGAAAACCTCACCCCG | 100 |

| mcbR-R | TTAATGATTTGTTCCA TGTCGCC | |

| flhD-F | AGAGTAATCGTCTGGTGG CTGTC | 122 |

| flhD-R | CGACAACATTAGCGGCACTG | |

| flhC-F | GGCTGGTGAGCGTGGGTAATA | 119 |

| flhC-R | AGTGCCCGCAAGCAGAAGAAG |

Statistical Analysis

The primers were designed with the Primer 5.0 software. Statistics were analyzed using SPSS (v19.0) software. A paired t test was used for statistical comparisons between groups. The level of statistical significance was set at a P-value of 0.05.

RESULTS

OmpR Upregulates Motility by Interfering With the Expression of Flagellum Genes

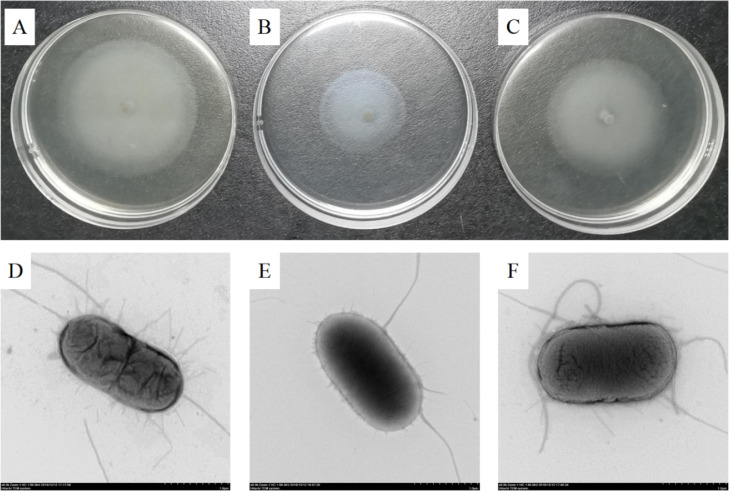

The mutant strain AE17ΔompR and the complement strain AE17C-ompR were successfully constructed by the CRISPR-Cas9 method (Figures 1A and 1B). Growth curves of the wild strain AE17, mutant strain AE17ΔompR, and the complement strain AE17C-ompR showed no significant difference in growth, suggesting OmpR did not affect the growth of APEC (Figure 1C). The deletion of the ompR gene resulted in significantly inhibited motility in the mutant strain AE17ΔompR, compared with AE17, and motility in the AE17C-ompR was not significantly different (Figure 2A-C). TEM showed that the flagella of wild strain AE17 were thin, long, and more numerous, while the flagella of the mutant strain AE17ΔompR were less numerous and those of the complement strain AE17C-ompR were more numerous (Figure 2D-F).

Figure 1.

(A) The schematic diagram of the strategy for deleting the ompR gene in AE17 using CRISPR-Cas9 system. (B) Confirmation of the wild-type strain AE17, mutant strain AE17ΔompR, and complement strain AE17C-ompR. M: 5 000 DNA marker; Lane 1: PCR product (2,617 bp) amplified from AE17 with primers ompR-out-F/R; Lane 2: PCR product (1,961 bp) amplified from AE17ΔompR with primers ompR-out-F/R; Lane 3: PCR product (493 bp) amplified from AE17 with primers ompR-in-F/R; Lane 4: PCR product (0 bp) amplified from AE17ΔompR with primers ompR-in-F/R; Lane 5: PCR product (493 bp) amplified from AE17 with primers ompR-in-F/R; Lane 6: PCR product (493 bp) amplified from AE17C-ompR with primers ompR-in-F/R; Lane 7-9: Negative control. (C) Growth curves of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains in LB medium.

Figure 2.

Bacterial motility and flagella of AE17, AE17ΔompR and AE17C-ompR strains. (A–C) Bacterial motility was assessed by examining the migration of bacteria through the agar from the centre of the plate to the periphery. (A) the motility circle of the wild strain AE17; (B) the motility circle of the mutant strain AE17ΔompR; (C) the motility circle of the complement strain AE17C-ompR. The diameters of the three strains of motility circles were 59.20 mm, 36.76 mm and 49.90 mm, respectively. (D, E) The flagella of AE17, AE17ΔompR and AE17C-ompR in the transmission electron micrographs views (× 8,000). (D) The morphological observation of AE17 (× 8,000); (E) the morphological observation of AE17ΔompR (× 8,000); (F) the morphological observation of AE17C-ompR (× 8,000).

OmpR Involved in Rdar Morphotype of APEC

As shown in Figure 3, the AE17 expresses a red, dry, and rough (rdar) morphotype on Congo red agar plates characterized by the extracellular matrix components cellulose and curli fimbriae. AE17ΔompR display a smooth and white (saw) colony morphology on plates, indicating that deletion of the ompR gene resulted in a lack of curli and cellulose production in AE17. The rdar morphotype was restored in AE17C-ompR. The results indicate that OmpR is involved in the production of curli and cellulose in APEC.

Figure 3.

Biofilm formation ability by crystal violet and scanning electron microscope. (A) Analyze the biofilm formation ability of AE17, AE17ΔompR and AE17C-ompR strains using a crystal violet assay; (B) (a) the morphological observation of AE17 (× 3,000); (b) the morphological observation of AE17ΔompR (× 3,000); (c) the morphological observation of AE17C-ompR (× 3,000).

OmpR Promotes the Biofilm Formation of APEC

In this study, the ability of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR to form biofilm was detected by crystal violet assay. As shown in Figure 4A, the biofilms were significantly decreased in the mutant strain AE17ΔompR, compared to that of the wild-type AE17, and the biofilms were restored in AE17C-ompR.

Figure 4.

Morphotypes of strains was investigated at 37°C on Congo red agar plates. (A) AE17 displays the rdar morphotype indicating co-expression of curli and cellulose; (B) AE17∆ompR results in the saw morphotype, indicating that neither curli nor cellulose is expressed; (C) AE17C-ompR also displays the rdar morphotype.

SEM showed that the biofilm of AE17 was thicker, with bacteria accumulating layer by layer and adhering closely to each other, while the biofilm of the AE17ΔompR strain was significantly weakened, and only a partial monolayer of bacteria could be observed. The adhesion between bacteria was looser, while the biofilm of the complemented strain AE17C-ompR was restored to some extent, and the connection between the bacteria was tighter (Figure 4B). These results indicated that OmpR affects biofilm formation in APEC.

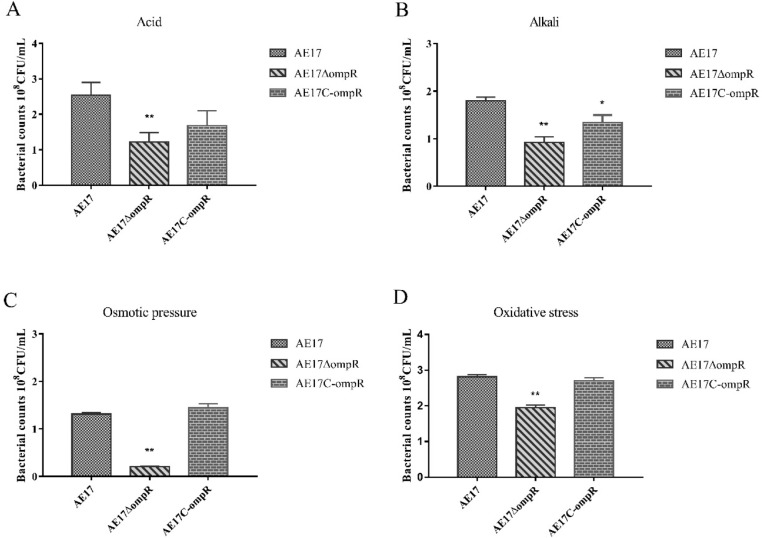

Deletion of the ompR Gene Was Responsible for Decreased Environmental Stresses

We compared the ability of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR to survive in diverse environmental stress. The results showed that the ability of AE17ΔompR to survive in diverse environmental stress was significantly reduced when compared to that of AE17, and the survival ability of AE17C-ompR was partially restored (Figure 5). These results suggested that OmpR plays an important role in bacterial adaption to different environmental stresses, including acid, alkali, osmotic, and oxidative stress.

Figure 5.

Determination the survival ability of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains under diverse environmental stress, including acid (A), alkali (B), osmotic stress (C), and oxidative stress (D). The ability of AE17ΔompR to survive in diverse environmental stress was significantly reduced when compared to that of AE17, and the survival ability of AE17C-ompR was partially restored(*P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01).

OmpR Contributed to the Survival Ability of APEC in Serum Resistance

The AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were incubated with SPF chicken serum at different dilutions (25, 50, 75, or 100%) at 37°C for 30 min. The result showed that the mutant strain AE17ΔompR was significantly susceptible to SPF chicken serum, compared with that of the wild-type strain AE17. And, the serum resistance was restored in the complement strain AE17C-ompR (Figure 6). The results indicated that the regulator OmpR is important for serum survival and is therefore essential for the pathogenesis of bacteria.

Figure 6.

Bacterial resistance to SPF chicken serum. The AE17, AE17∆ompR, and AE17C-ompR strains were incubated with different dilutions of SPF chicken serum (5, 12.5, 25, 100% and heat inactivated serum) at 37°C for 30 min. The mutant strain AE17ΔompR was significantly susceptible to SPF chicken serum, compared with that of AE17. The data represent the averages of three trials (*P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01).

OmpR Increased Adherence and Invasion to DF-1 Cells

The survival ability of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR strains in DF-1 cells were performed. The adhesion ability of AE17ΔompR to DF-1 cells was significantly decreased, compared with that of wild-type AE81 (Figure 7A). The ability of AE17ΔompR to invade DF-1 cells was also significantly decreased, compared with that of wild-type AE81 (Figure 7B). These results indicate that OmpR influences the ability of APEC to adhere and invade DF-1 cells.

Figure 7.

Adhesion and invasion to DF-1 cells. The counts of AE17, AE17ΔompR, and AE17C-ompR to DF-1 cells were calculated. The counts of AE17ΔompR to DF-1 cells were significantly lower than that of AE17 (*P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01).

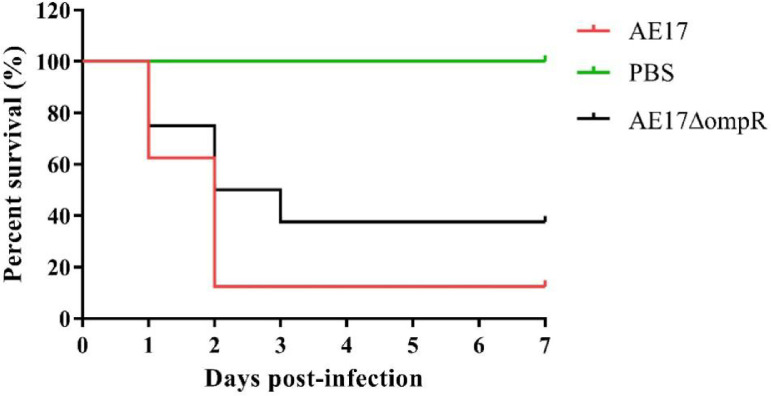

OmpR is Necessary for APEC Virulence in Vivo

To investigate whether OmpR was involved in bacterial virulence, chicks were infected with 106 CFU of the wild-type strain AE17 and mutant strain AE17ΔompR. Mortality was observed for 7 d postchallenge. As shown in Figure 8, the mortality of AE17 and AE17ΔompR was 87.5% (7/8) and 62.5% (5/8), respectively. These results indicate that the deletion of the ompR gene led to the attenuation of virulence in chickens.

Figure 8.

Determination of bacterial virulence. Seven-day-old chickens were infected intramuscularly with AE17, AE17ΔompR at 106CFU. Negative controls were injected with PBS. Survival was monitored until 7 d postinfection.

OmpR Upregulates the Expression of Virulence Genes

The qRT-PCR analyzed a range of virulence-related genes, including fimbriae, flagellar, and biofilm formation genes, to explore the role of ompR in the virulence regulation of APEC. RT-qPCR results showed that the transcription levels of the flagellar genes flhD, flhC, and cheY, the type Ⅰ fimbriae gene fimF, fimG, and fimH, and the biofilm formation genes csgD, ompA, tolC, and mcbR were significantly downregulated in the mutant strain AE17ΔompR, compared with those in the wild-type AE17 strain. The transcription levels of these genes were restored in the complement strain AE17C-ompR (Figure 9). This result suggests that OmpR plays an important regulatory role in APEC pathogenesis.

Figure 9.

Relative expression of virulence genes was tested with qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to the housekeeping gene dnaE. X-axis represents different genes. The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−△△Ct method (*P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The TCS functions as a regulator control system that is involved in the response to external environment signals, bacterial drug resistance, and pathogenesis. The TCS consists of a histidine kinase that detects signals or stimuli and undergoes auto-phosphorylation, and a response regulator activated by the histidine kinase that acts as a transcriptional regulator altering gene expression (Breland et al., 2017). Different response regulators with a role in APEC pathogenesis have been reported. The regulator PhoP of PhoP/Q TCS positively regulates APEC flagella, biofilm formation, and pathogenicity, and regulates the expression of virulence genes (Yin et al., 2019). The Cpx TCS response regulator CpxR is critical to the virulence of APEC and regulates the expression of the type VI secretion system 2 (T6SS2) (Yi et al., 2019). The QseB, a response regulator of the QseBC TCS, functions as a global regulator of flagella, biofilm formation, and virulence (Ji et al., 2017). The OmpR/EnvZ system is a key TCS that plays an important role in response to environmental osmotic pressure and pathogenicity in most Gram-negative bacteria (Prigent-Combaret et al., 2001). However, the function of the response regulator OmpR is not yet understood in the APEC.

As already known, several factors have been reported to affect the flagella formation of APEC, including YqeI, ArcA, and YjjQ (Jiang et al., 2015a; Wiebe et al., 2015; Xue et al., 2020b). In this study, the ompR gene significantly influenced its motility in APEC O2 strain. Flagella are important motility structures and virulence factors of bacteria that participate in bacterial movement, chemotaxis, surface attachment, and invasion of host cells (Prigent-Combaret et al., 2000). The qRT-PCR results show that the OmpR regulates the flagella-associated genes flhD, flhC, cheY, fimF, fimG, fimH, and csgD. In E. coli K-12, the regulator OmpR regulates the flagella-associated genes flhD, flhC, fimB, and csgD (Jubelin et al., 2005; Rentschler et al., 2013; Samanta et al., 2013). OmpR directly binds to the flagellar master operon flhDC promoter in Yersinia enterocolitica (Raczkowska et al., 2011). Consistent with the results for E. coli K-12 and Y. enterocolitica, we found that OmpR also affects the expression of flhDC genes in APEC. The flagellar synthesis master promoter flhDC responds to environmental signals and transcribes under complex regulation, which in turn activates the secondary promoter and tertiary flagellar genes (Raczkowska et al., 2011).

To survive in different environments, pathogens need to adapt rapidly to different conditions (Chakraborty and Kenney, 2018). In this study, we demonstrated that OmpR is involved in responding to various external environmental changes, including acid, alkali, oxidative stress, and osmotic pressure. In non-pathogenic E. coli K12, the OmpR controls the expression of outer membrane porins OmpF and OmpC in response to environmental osmotic pressure. In Y. enterocolitica, OmpR was identified as the response regulator for osmolarity-regulated porins (Brzóstkowska et al., 2012). OmpR contributes to cytoplasmic acidification by repressing the cadC/BA operon during acid stress in S. Typhimurium and E. coli (Chakraborty et al., 2015, 2017). The curli fimbriae play important roles in bacterial adhesion, biofilm formation, and host pathogenesis in E. coli (Barnhart and Chapman, 2006). The previous study showed that EnvZ, a histidine kinase, contributes to the biofilm formation of APEC and regulates the expression of biofilm-associated genes (Feng et al., 2021). In this study, the deletion of the ompR gene decreased the biofilm formation of APEC and resulted in a lack of curli and cellulose production in APEC, as well as the downregulation of transcript levels of the csgD, ompA, tolC, and mcbR genes. CsgD, a master transcriptional regulator of curli assembly, activates the production of curli fimbriae and cellulose via the positive regulation of the csgBAC operon and regulates the expression of biofilm formation genes (Ogasawara et al., 2011). The membrane protein TolC is involved in biofilm formation and curli production of the ExPEC strain (Hou et al., 2014). In E. coli, the OmpR binds the csgD promoter region and promotes biofilm formation and curli production (Prigent-Combaret et al., 2001).

In adherent-invasive E. coli (AIEC), OmpR is involved in vitro adhesion and invasion to human intestinal epithelial T84 cells (Lucchini et al., 2021). In this study, OmpR contributes to the adhesion and invasion of DF-1 cells and also regulates the expression of type I fimbriae genes (fimF, fimG, and fimH) and the csgD gene. In E. coli, OmpR binds the CsgD promoter and affects adhesion (Prigent-Combaret et al., 2001). Serum resistance contributes to septicemia and mortality of APEC during colonization and survival in the host (Mellata et al., 2003; Li et al., 2011). Outer membrane proteins contribute to the serum resistance of APEC (Mellata et al., 2003). In this study, the ompR contributed to sensitivity in SPF chicken serum, which might decrease the expression of biofilm formation. The deletion of the ompR gene downregulates the expression of the ompA gene, encoding the outer membrane proteins OmpA, associated with serum resistance (Nielsen et al., 2020). These findings suggest that OmpR plays an important role in the adhesion to host cells and serum resistance, suggesting OmpR plays an important role in the pathogenicity of APEC O2 strain.

In summary, the regulator OmpR participates in the pathogenicity of APEC O2 strain, including attenuated bacterial flagellum formation and motility, reduced biofilm formation, impaired survival in diverse environmental stress, and serum resistance, and diminished adhesion and invasion to DF-1 cells in APEC. The regulator OmpR participates in the pathogenicity of APEC and provides insight for the further research of APEC pathogenicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31772707, 31972644), the University Synergy Innovation Program of Anhui Province (Grant No. GXXT-2019-035).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- Barnhart M.M., Chapman M.R. Curli biogenesis and function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;60:131–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland E.J., Eberly A.R., Hadjifrangiskou M. An overview of two-component signal transduction systems implicated in extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017;7:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzóstkowska M., Raczkowska A., Brzostek K. OmpR, a response regulator of the two-component signal transduction pathway, influences inv gene expression in Yersinia enterocolitica O9. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012;2:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S.J., Inouye M. EnvZ-OmpR interaction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24155–24161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A.D.S., Dorman C.J. A fundamental regulatory mechanism operating through OmpR and DNA topology controls expression of Salmonella pathogenicity islands SPI-1 and SPI-2. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capra E.J., Laub M.T. Evolution of two-component signal transduction systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;66:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Kenney L.J. A new role of OmpR in acid and osmotic stress in Salmonella and E. coli. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Mizusaki H., Kenney L.J. A FRET-based DNA biosensor tracks OmpR-dependent acidification of Salmonella during macrophage infection. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:1–32. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Winardhi R.S., Morgan L.K., Yan J., Kenney L.J. Non-canonical activation of OmpR drives acid and osmotic stress responses in single bacterial cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanteloup N.K., Porcheron G., Delaleu B., Germon P., Schouler C., Moulin-Schouleur M., Gilot P. The extra-intestinal avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain BEN2908 invades avian and human epithelial cells and survives intracellularly. Vet. Microbiol. 2011;147:435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M.E., Yeh I.H., Sung L.Y., Wu M.Y., Chao Y.P., Ng I.S., Hu Y.C. Enhanced integration of large DNA into E. coli chromosome by CRISPR/Cas9. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017;114:172–183. doi: 10.1002/bit.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper V.S. The OmpR regulator of burkholderia multivorans controls mucoid-to-nonmucoid transition and other cell. Envelope. 2018;200:1–22. doi: 10.1128/JB.00216-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Oropeza R., Kenney L.J. Dual regulation by phospho-OmpR of ssrA/B gene expression in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:1131–1143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H., Xue M., Lu H., Gu Y., Shao Y., Song X., Tu J., Qi K. Mechanism of histidine kinase gene envZ regulating biofilm of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2021;42:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Foo Y.H., Gao Y., Zhang H., Kenney L.J. Cytoplasmic sensing by the inner membrane histidine kinase EnvZ. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2015;118:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q., Ye Z., Wang X., Mu X., Gao S., Liu X. RstA is required for the virulence of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O2 strain E058. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;29:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P.M., Manges A.R., Johnson J.R. Food-borne origins of Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:712–719. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou B., Meng X.R., Zhang L.Y., Tan C., Jin H., Zhou R., Gao J.F., Wu B., Li Z.L., Liu M., Chen H.C., Bi D.R., Li S.W. TolC promotes ExPEC biofilm formation and curli production in response to medium osmolarity. Biomed Res. Int. 2014;2014:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2014/574274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.H., Chi F., Wang Y., Gallaher T.K., Wu C.H., Jong A. Identification of IbeR as a stationary-phase regulator in meningitic Escherichia coli K1 that carries a loss-of-function mutation in rpoS. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2009;2009:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2009/520283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Li W., Zhang Y., Chen L., Zhang Y., Zheng X., Huang X., Ni B. QseB mediates biofilm formation and invasion in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Microb. Pathog. 2017;104:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., An C., Bao Y., Zhao X., Jernigan R.L., Lithio A., Nettleton D., Li L., Wurtele E.S., Nolan L.K., Lu C., Li G. ArcA controls metabolism, chemotaxis, and motility contributing to the pathogenicity of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:3545–3554. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00312-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Chen B., Duan C., Sun B., Yang J., Yang S. Multigene editing in the Escherichia coli genome via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:2506–2514. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04023-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubelin G., Vianney A., Beloin C., Ghigo J.M., Lazzaroni J.C., Lejeune P., Dorel C. CpxR/OmpR interplay regulates curli gene expression in response to osmolarity in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2038–2049. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2038-2049.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.K., Detweiler C.S., Falkow S. OmpR regulates the two-component system SsrA-SsrB in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:771–781. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.771-781.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Tivendale K.A., Liu P., Feng Y., Wannemuehler Y., Cai W., Mangiamele P., Johnson T.J., Constantinidou C., Penn C.W., Nolan L.K. Transcriptome analysis of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O1 in chicken serum reveals adaptive responses to systemic infection. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:1951–1960. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01230-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchini V., Sivignon A., Pieren M., Gitzinger M., Lociuro S., Barnich N., Kemmer C., Trebosc V. The role of OmpR in bile tolerance and pathogenesis of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.684473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter L.B., Ares M.A., Abundes-Gallegos J., Cedillo M.L., Yáñez J.A., Martínez-Laguna Y., De la Cruz M.A., Girón J.A. The CpxRA stress response system regulates virulence features of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;20:3363–3377. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellata M. Human and avian extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: infections, zoonotic risks, and antibiotic resistance trends. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013;10:916–932. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellata M., Dho-Moulin M., Dozois C.M., Curtiss R., Brown P.K., Arné P., Brée A., Desautels C., Fairbrother J.M. Role of virulence factors in resistance of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli to serum and in pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:536–540. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.536-540.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato G., de Campos T.A., Stehling E.G., Brocchi M., da Silveira W.D. Virulence factors of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2009;29:479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Nieckarz M., Raczkowska A., Kistowski M., Dadlez M., Heesemann J., Rossier O., Brzostek K. Impact of OmpR on the membrane proteome of Yersinia enterocolitica in different environments : repression of major adhesin YadA and heme receptor HemR. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:997–1021. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen D.W., Ricker N., Barbieri N.L., Allen H.K., Nolan L.K., Logue C.M. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. BMC Res. Notes. 2020;13:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-4917-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara H., Yamamoto K., Ishihama A. Role of the biofilm master regulator CsgD in cross-regulation between biofilm formation and flagellar synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:2587–2597. doi: 10.1128/JB.01468-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent-Combaret C., Brombacher E., Vidal O., Ambert A., Lejeune P., Landini P., Dorel C. Complex regulatory network controls initial adhesion and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli via regulation of the csgD gene. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:7213–7223. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7213-7223.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent-Combaret C., Prensier G., Le Thi T.T., Vidal O., Lejeune P., Dorel C. Developmental pathway for biofilm formation in curli-producing Escherichia coli strains: role of flagella, curli and colanic acid. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;2:450–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn H.J., Cameron A.D.S., Dorman C.J. Bacterial regulon evolution: distinct responses and roles for the identical OmpR proteins of Salmonella Typhimurium and Escherichia coli in the acid stress response. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raczkowska A., Skorek K., Bielecki J., Brzostek K. OmpR controls Yersinia enterocolitica motility by positive regulation of flhDC expression. Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;99:381–394. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9503-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez R.M., Almanza Y., García S., Heredia N. Adherence and invasion of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli to avian tracheal epithelial cells. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;25:1019–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Reboul A., Lemaître N., Titecat M., Merchez M., Deloison G., Ricard I., Pradel E., Marceau M., Sebbane F. Yersinia pestis requires the 2-component regulatory system OmpR-EnvZ to resist innate immunity during the early and late stages of plague. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210:1367–1375. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentschler A.E., Lovrich S.D., Fitton R., Enos-Berlage J., Schwan W.R. OmpR regulation of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli fimB gene in an acidic/high osmolality environment. Microbiol. (United Kingdom). 2013;159:316–327. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.059386-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolhion N., Carvalho F.A., Darfeuille-Michaud A. OmpC and the σE regulatory pathway are involved in adhesion and invasion of the Crohn’s disease-associated Escherichia coli strain LF82. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1684–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta P., Clark E.R., Knutson K., Horne S.M., Prüß B.M. OmpR and RcsB abolish temporal and spatial changes in expression of flhD in Escherichia coli Biofilm. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Li C., Qi K., Tu J., Liu H., Xue T. The role of the outer membrane protein gene ybjX in the pathogenicity of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Avian Pathol. 2018;47:294–299. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2018.1448053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu J., Huang B., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Xue T., Li S., Qi K. Modulation of virulence genes by the two-component system PhoP-PhoQ in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2016;19:31–40. doi: 10.1515/pjvs-2016-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Bao Y., Meng Q., Xia Y., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Tang F., Zhuge X., Yu S., Han X., Dai J., Lu C. IbeR facilitates stress-resistance, invasion and pathogenicity of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2015;10:5–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.T., Kuo C.J., Huang C.W., Lee T.M., Chen J.W., Chen C.S. OmpR coordinates the expression of virulence factors of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in the alimentary tract of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Microbiol. 2021;116:168–183. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe H., Gürlebeck D., Groß J., Dreck K., Pannen D., Ewers C., Wieler L.H., Schnetz K. YjjQ represses transcription of flhDC and additional loci in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:2713–2720. doi: 10.1128/JB.00263-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Lv X., Lu J., Yu S., Jin Y., Hu J., Zuo J., Mi R., Huang Y., Qi K., Chen Z., Han X. The role of the ptsI gene on AI-2 internalization and pathogenesis of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 2017;113:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M., Raheem M.A., Gu Y., Lu H., Song X., Tu J., Xue T., Qi K. The KdpD/KdpE two-component system contributes to the motility and virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020;131:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Li Q., Xue M., Wang Z., Tu J., Song X., Shao Y., Han X., Xue T., Liu H., Qi K. The role of the phoP transcriptional regulator on biofilm formation of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Avian Pathol. 2019;48:362–370. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2019.1605147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Wang H., Han X., Li W., Xue M., Qi K., Chen X., Ni J., Deng R., Shang F., Xue T. The two-component system, BasSR, is involved in the regulation of biofilm and virulence in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Avian Pathol. 2020;49:532–546. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2020.1781791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M., Xiao Y., Fu D., Raheem M.A., Shao Y., Song X. Transcriptional regulator YqeI, locating at ETT2 locus, affects the pathogenicity of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Animals (Basel). 2020;10:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ani10091658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z., Wang D., Xin S., Zhou D., Li T., Tian M., Qi J., Ding C., Wang S., Yu S. The CpxR regulates type VI secretion system 2 expression and facilitates the interbacterial competition activity and virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Vet. Res. 2019;50:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13567-019-0658-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]