Abstract

There is more than one pathway to romance, but relationship science does not reflect this reality. Our research reveals that relationship initiation studies published in popular journals (Study 1) and cited in popular textbooks (Study 2) overwhelmingly focus on romance that sparks between strangers and largely overlook romance that develops between friends. This limited focus might be justified if friends-first initiation was rare or undesirable, but our research reveals the opposite. In a meta-analysis of seven samples of university students and crowdsourced adults (Study 3; N = 1,897), two thirds reported friends-first initiation, and friends-first initiation was the preferred method of initiation among university students (Study 4). These studies affirm that friends-first initiation is a prevalent and preferred method of romantic relationship initiation that has been overlooked by relationship science. We discuss possible reasons for this oversight and consider the implications for dominant theories of relationship initiation.

Keywords: romantic relationships, close relationships, friendship, dating, relationship initiation

I have never been on a date and probably never will…I have always done the friends-to-lovers pathway, where you just start sleeping with your best friend and then move in…Sometimes I really regret this, and get jealous of people who get pretty and put on their best selves, and go outside to have adventures with strangers.

—Tumblr user @elodieunderglass (2017)

According to online blogger, @elodieunderglass, there are at least two ways to initiate a romantic relationship. As she describes in the quote, above, one way involves dating: getting dressed up and having “adventures with strangers.” The other way is a “friends-to-lovers pathway” that involves sleeping with your best friend and then, basically, getting married. Any self-respecting consumer of popular culture or gossip at the local coffee shop will recognize the truth of these descriptions. Movies, television, popular media, and most groups of friends abound with examples of strangers striking up a conversation at a social function and then falling in love during a series of romantic excursions, or slow-blooming attractions between friends that eventually reveal themselves in late-night cathartic conversations (and make-out sessions). Yet despite the cultural ubiquity of both of these pathways to romantic love, we have noticed that relationship science focuses almost exclusively on the former, which we call dating initiation. Indeed, in the 20 years that we have been studying these processes, we have encountered only a few published empirical studies in social and personality science that explore the friends-to-lovers pathway to romance, which we call friends-first initiation. We test this observation in the current research, while also assessing the prevalence of and people’s preferences for each type of initiation.

The Challenge of Studying Relationship Initiation

Relationship scientists’ empirical attention has not been evenly distributed along the trajectory of romance (Eastwick et al., 2019). For example, researchers have devoted considerable attention to studying the initial spark of attraction that kindles between two strangers meeting for the first time. Or, to be perfectly accurate, researchers have devoted considerable attention to studying the spark of attraction that kindles when someone views a photograph, reads a brief biography, or views a list of traits that may be possessed by a potential romantic partner. However, as Eastwick and colleagues point out, a lot can happen between a spark of attraction and maintaining a committed romantic relationship. Unfortunately, because “[t]he initial attraction literature does not intersect empirically with the literature on established romantic relationships” (Eastwick et al., 2019, p. 2), researchers remain mostly in the dark about what those processes might be.

There are valid reasons why researchers may neglect to study relationship initiation beyond the moments of initial attraction. Simply put, it is hard. Relationship initiation may occur in private places like homes or workplaces that are difficult for researchers to access. Meeting a new romantic partner may occur randomly and spontaneously, or romance may emerge from a long-term friendship. In contrast, paradigms that enhance scientific control (e.g., introducing strangers) are easy alternatives to studying the messier, naturalistic processes of relationship initiation. Yet beyond these practical constraints, we also suggest that efforts to study relationship initiation may have been hampered by cultural scripts that shape, and sometimes limit, scientific inquiry.

Cultural scripts are cognitive structures that organize how people understand and remember important life events, including romantic experiences (e.g., Berntsen & Rubin, 2004). For example, the Western dating script explains the series of stereotyped actions that people should take to initiate a relationship (e.g., Cameron et al., 2013; Laner & Ventrone, 2000). According to this script, relationships start because sexual attraction prompts men to use bold and direct behaviors to make their interest known to women, while women focus on making themselves attractive and waiting for men to “make a move.” As this example makes painfully clear, dating scripts are heterosexist—that is, they reflect an ideology that values and prioritizes heterosexual relationships while stigmatizing and marginalizing nonheterosexual ways of being—and they have remained largely unchanged since researchers began documenting their content in the 1950s (Cameron & Curry, 2020; Rose, 2000). Although these cultural scripts describe dating initiation, there is no equivalent script for friends-first initiation (Mongeau & Knight, 2015). We suggest that these cultural biases may have hampered efforts to understand the varied pathways that lead to romance.

Pathways to Romance

Relationship scientists have long understood that there are at least two kinds of intimacy (e.g., Berscheid, 2010; Guerrero & Mongeau, 2008). One is friendship-based intimacy, which is a cognitive and emotional experience comprising psychological interdependence, warmth, and understanding, related to the companionate love that nurtures long-term intimate bonds. The other is passion-based intimacy, which is a primarily emotional experience comprising romance and positive arousal, related to the passionate love that typifies novel, and often sexual, relationships. The dominant, but heterosexist, dating script proposes that men’s passionate desire sparks the initial interaction between potential romantic partners and then passion-based intimacy and friendship-based intimacy continue to develop over time in tandem.

However, in her biobehavioral model of sexual orientation, Diamond (2003) convincingly argues that while emotional affection (i.e., friendship-based intimacy) and sexual desire are distinct, the biobehavioral links between systems are bidirectional. Thus, even though sexual desire can precede and even nurture friendship-based intimacy, as the dating script prescribes, the opposite can also occur: Two people can become friends, develop a deep friendship-based intimacy and then begin to experience sexual desire at some future point in time. Now, the dating script might suggest that such friendships are not truly platonic, and concealed passionate desire is the true motivation behind such bonds. After all, some 30%–60% of (presumably heterosexual) cross-sex friends report at least moderate sexual attraction for one another (e.g., Halatsis & Christakis, 2009; Kaplan & Keys, 1997). Yet the empirical evidence is clear that friendship-based intimacy can precede and even nurture passion-based intimacy (see Rubin & Campbell, 2012). When this happens, the friends may decide not to act on their passion (Bleske-Rechek et al., 2012), or they may form a “friends-with-benefits” relationship, where they engage in sexual activity with rules to limit emotional attachment (Mongeau & Knight, 2015). Yet while friends-with-benefits relationships are very common among young people, only a very small proportion ever transition to a traditional romantic relationship (Bisson & Levine, 2009; Machia et al., 2020).

Thus, most friendships that eventually transition to romance must follow a different path. Indeed, as Diamond (2003) reviews, the friends-first pathway to romance is well-documented among people who experience same-gender/sex 1 attractions, even among people who self-identify as heterosexual. Furthermore, Eastwick and colleagues (2019) note that the few studies examining the trajectory of early romance suggest that people often know one another for months or even years before they officially enter couplehood. Although it was not the primary focus of the research, two longitudinal studies of romantic relationships between men and women report that a meaningful proportion began as friendships (Eastwick et al., 2019; Hunt et al., 2015). Together with Diamond’s (2003) research, these longitudinal studies suggest that romantic and sexual attraction can blossom within long-standing platonic friendships between people of all genders, and sometimes those feelings can lead to romantic couplehood.

The Current Research

We present four studies designed to quantify the extent of researchers’ potential neglect of friends-first initiation as well as the prevalence of and people’s preferences for this form of initiation. In Studies 1 and 2, we systematically code the literature on relationship initiation to determine how often researchers study dating versus friends-first initiation. In Study 3, we seek to establish the prevalence of friends-first initiation with a meta-analysis of seven studies that we have conducted, involving nearly 1,900 participants. We also explore group differences in the prevalence of friends-first initiation (i.e., gender, age, sample population [students vs. MTurk workers], education level, ethnicity, gender composition of the couple), and we explore the prevalence of friends-with-benefits relationships among now-married friends-first initiators. In Study 4, we delve deeper by exploring how long university students were friends prior to couplehood and whether they entered those friendships to facilitate an eventual romance. Participants also report the “best way to meet a dating or romantic partner,” allowing us to assess their preference for friends-first initiation.

If our descriptive and exploratory results reveal that friends-first initiation is a prevalent and preferred method of relationship initiation that is relatively overlooked in relationship science, it will suggest that researchers need to revisit the validity of dominant models of relationship formation, all of which were devised based on research that likely focuses almost exclusively on dating initiation, and all of which may operate very differently during friends-first initiation. For example, one of the only in-depth studies of friendship initiation to date revealed that assortative mating for physical attractiveness was much weaker among friends-first initiators compared to dating initiators (Hunt et al., 2015). Furthermore, although first dates involving (presumably heterosexual) women and men typically follow gender-role prescriptions, expectations for first dates are more egalitarian during friends-first initiation, which may alter the power structure of developing relationships (Cameron & Curry, 2020; see also Rose, 2000). Friendship-based intimacy is also the foundation of long-lasting romantic bonds (VanderDrift et al., 2016), and thus understanding how and when people transition from friendship to romance may help researchers to understand the social–psychological foundations of strong and satisfying romantic relationships. In addition, exploring the transition from friendship to romance reveals the messy reality of relationship initiation, which belies the orderly sexual scripts that dominate Western culture. We will return to these issues in the Discussion, but in general, we suspect that by overlooking friends-first initiation, psychologists may have a surprisingly limited understanding of how people actually form romantic relationships.

Study 1

In Study 1, we systematically coded the literature on relationship initiation to determine how often researchers study dating versus friends-first initiation.

Method

Complete search and coding rules, data, and analysis code are posted in the Online Supplemental Materials (OSM): https://osf.io/3s5tm/

Research assistants and the first author searched the PsycInfo database for empirical publications pertaining to relationship initiation using the following search terms: relationship initiation; relationship-initiation; date initiation; first date; relationship overture; first date overture; date overture; relationship beginning; initial interaction; attraction; friendship; friends with benefits. We restricted our search to 11 high impact journals that often publish relationship science conducted by social and personality psychologists: Archives of Sexual Behavior; Journal of Experimental Social Psychology; Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; Journal of Social and Personal Relationships; Journal of Sex Research; Personal Relationships; Personality and Individual Differences; Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin; Psychological Science; Sex Roles; Social Psychological and Personality Science. Thus, our search was not intended to provide a complete overview of the field; we code a sampling of articles concerning relationship initiation, and our results presumably could generalize to other journals.

We included articles in our sample that described the initiation process for a romantic relationship, including the intention to engage in initiation behaviors and/or actual romantic relationship initiation. We excluded articles about mate poaching, cheating, and the temptation to cheat, and articles concerning mate preferences and attraction when they examined these processes in abstract or without reference to a particular person or relationship (e.g., rating the importance of traits, rating the attractiveness of photographs). We excluded these subjects in part to restrict our search to a more manageable scope, but also because our initial searches of the literature led us to conclude that these fields often use hypothetical or abstract methods (e.g., rate a list of traits; imagine a given situation). As such, the excluded topics appear to exclusively study dating initiation (i.e., how can one be friends-first with a hypothetical mate or novel photograph?), and thus excluding these topics may actually provide a stricter estimate of the extent to which researchers focus on dating initiation versus friends-first initiation. We also excluded articles about friends-with-benefits relationships that did not describe the transition to romance (actual or planned).

This search revealed 108 relevant empirical publications. One research assistant coded the first 64 publications and the second coded 31 of those publications to establish interrater reliability. The first and third authors both coded the remaining 44 publications. Coders recorded the type of interpersonal relationship that was the focus of each publication: romance, friendship, relationships in general (i.e., general relationship processes like trust, similarity, communication, etc.), and other/unclear. Coders also indicated whether the relationship-initiation context was dating initiation, friends-first initiation, both, or other/unclear. Interrater reliability was excellent for relationship type (90% agreement, κ = .80), and context (95% agreement, κ = .87). Disagreements between the coders were resolved by the second author.

Results and Discussion

Seventy-nine percentage (n = 85) of the sampled publications concerned romantic relationship initiation (Table 1). Of these, 74% (n = 63) concerned dating initiation while only 8% (n = 7) focused on friends-first initiation (Table 2). A further 9% (n = 8) concerned both types of initiation, and if we include these articles in both counts, then 84% of articles concerned dating initiation while only 18% concerned friends-first initiation. These results suggest that researchers largely overlook friends-first initiation and overwhelmingly focus on dating initiation in their empirical study of relationship initiation (articles are listed in the OSM).

Table 1.

Frequency of Relationship Types in Sampled Relationship Initiation Articles in Studies 1 and 2.

| Relationship Type | Study 1: Journal Publications (108 Articles) |

Study 2: Textbook Citations (43 Articles) |

|---|---|---|

| Romance | 85 | 38 |

| Friendship | 9 | 1 |

| Relationships general | 6 | 0 |

| Other/unclear | 8 | 4 |

Table 2.

Frequency of Initiation Context Types in Articles Coded as Pertaining to “Romance” in Studies 1 and 2.

| Relationship Context | Study 1: Journal Publications (85 Articles Total) |

Study 2: Textbook Citations (38 Articles Total) |

|---|---|---|

| Dating initiation | 63 | 30 |

| Friends-first initiation | 7 | 2 |

| Both | 8 | 5 |

| Other/unclear | 7 | 1 |

Note. Articles coded as “other/unclear” typically studied general initiation processes and/or did not specify a relationship context. See the Online Supplementary Materials for more examples.

Study 2

Next, we searched two popular close relationships textbooks and systematically coded the cited literature on relationship initiation to determine the extent to which education about relationship initiation focuses on dating versus friends-first initiation.

Method

Complete search and coding rules, data, and analysis code are available in the OSM.

The first and second authors searched two popular textbooks on intimate relationships (Bradbury & Karney, 2019; Miller, 2017) for articles pertaining to relationship initiation. They searched the entirety of any chapters devoted to attraction, friendship, or sexuality and searched the index for references to “attraction,” “courtship,” “dating,” “initiation,” “romantic,” “friendship,” and “friends with benefits.” We used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria for articles as Study 1. After eliminating duplicate citations (n = 1), books, and reviews, we were able to identify 43 relevant empirical publications.

Eight of the 43 articles were coded in Study 1 (see OSM); we imported those codes for this analysis. Two research assistants coded five articles and the first and third authors coded the remaining 38 publications for type of relationship initiation and initiation context. Interrater reliability was excellent for relationship type (95% agreement; κ = .84) and context (77% agreement, κ = .70). Disagreements were resolved by the second author.

Results and Discussion

Eighty-eight percentage (n = 38) of the cited articles pertained to romantic relationship initiation (Table 1). Of these, 79% (n = 30) concerned dating initiation, whereas just 5% (n = 2) focused on friends-first initiation (Table 2). Another 13% (n = 5) focused on both types of initiation, and when we included these articles in both counts, 92% of the articles concerned dating initiation while 18% concerned friends-first initiation. Once again, these results suggest that relationship science focuses on dating initiation and largely overlooks friends-first initiation (articles are listed in the OSM).

Study 3

Next, we sought to establish the prevalence of friends-first initiation. We performed a meta-analysis of seven studies conducted in our labs. In each, participants indicated if they were friends with their current or a past romantic partner before they became romantically involved.

Method

Participants (N = 1,897) took part in seven studies that our labs conducted between 2002 and 2020 for other purposes. In all studies, the data that we report have not been published previously and were collected as part of the demographic survey prior to any experimental manipulations (if present; publications reporting other data from these samples are described in the OSM). Samples 1–5 were undergraduate students living in two regions in Canada who received partial course credit in appreciation for their time. Samples 6 and 7 included crowdsourced adults living in Canada or the United States who received a small monetary reward in appreciation for their time.

We report the sampling and exclusion rules for each sample in the OSM. Because data for Studies 1–6 were conducted before current open science norms were adopted, we do not have consent to share participant data. Data for Sample 7 are available in the OSM. Detailed sample demographics are reported in the OSM.

Sample 1. Sample 1 comprised 60 introductory psychology students who were single (43.3%) or in a romantic relationship (56.7%). Participants reported on their most recent successful initiation attempt by choosing a response to the following question: “What was your relationship with your partner before [you became romantically involved]?” (response options: (a) friends; (b) a friend of a friend; (c) acquaintances; (d) worked together; (e) had never met before [strangers]; (f) other). We recorded the percentage of participants who chose the option “(a) friends.”

Sample 2. Sample 2 comprised 92 introductory psychology students who were currently involved in a romantic relationship. Participants reported whether they were friends with their current romantic partner before they became romantically involved (yes or no).

Sample 3. Sample 3 comprised 191 introductory psychology students who were currently involved in a romantic relationship. Participants reported whether they were friends with their current romantic partner before they became romantically involved (yes or no).

Sample 4. Sample 4 comprised 243 introductory psychology students who were currently involved in a romantic relationship. Participants reported whether they were friends with their current romantic partner before they became romantically involved (yes or no).

Sample 5. Sample 5 comprised 298 introductory psychology students. Single participants (55.7%) reported whether they were friends with their most recent romantic partner before they became involved, whereas partnered participants (44.3%) reported whether they were friends with their current partner before they became involved (yes or no).

Sample 6. Sample 6 comprised 336 crowdsourced adults who were currently involved in a romantic relationship. Participants reported whether they were friends with their current romantic partner before they became romantically involved (yes or no).

Sample 7. Sample 7 comprised 677 crowdsourced adults who were currently married or in a common law partnership. Participants reported whether they were friends with their spouse before they became romantically involved (yes or no).

Results and Discussion

Most participants reported that their romantic relationships began as friendships (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of Each Sample Reporting That They Were Friends Prior to Becoming Romantic Partners.

| Sample | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 40.0 |

| 2 | 92 | 65.2 |

| 3 | 191 | 70.7 |

| 4 | 243 | 72.8 |

| 5 | 298 | 70.5 |

| 6 | 336 | 62.2 |

| 7 | 677 | 70.6 |

| Weighted mean | 68.2 | |

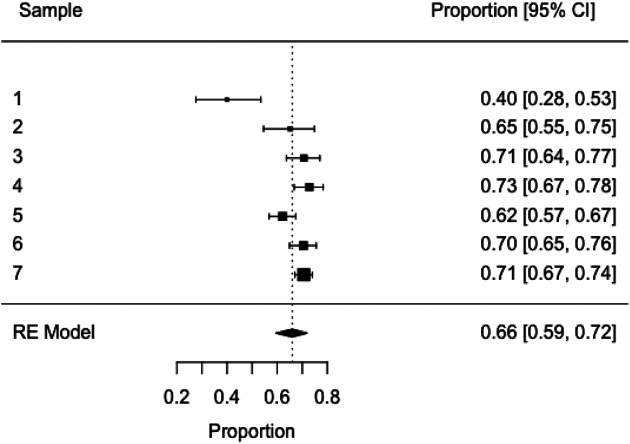

A meta-analysis of proportions using an exact binomial-normal model and logit transformed proportions (e.g., Hamza et al., 2008) with the metafor package in RStudio (metafor version 2.4-0; Viechtbauer, 2010; RStudio version 3.6.2) revealed a median proportion of 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI] = [0.59, 0.72]), and an estimated average log-odds of 0.66 (SE = 0.14), 95% CI [0.38, 0.95], z = 4.62, p < .001, indicating that the majority of romantic relationships began as friendships (see Figure 1 for forest plot and the OSM for R code). There was also significant heterogeneity among studies, Wald (6) = 31.01, p < .001, I 2 = 86%, H 2 = 7.14, τ2 = 0.12, indicating that effect sizes varied across studies perhaps due to the use of different measures. These results reveal that friends-first initiation is a common form of relationship initiation.

Figure 1.

Forest plot reflecting the proportion of participants (total sample) who were friends first in each sample. Note. The squares represent each study’s estimate, with the size of the square representing the weight of the estimate and the lines representing the 95% confidence interval. The diamond represents the random effects point estimate, its width the 95% confidence interval, and the dotted vertical line represents the overall combined mean effect estimate.

We also explored whether the prevalence of friends-first initiation differed between various groups. Brief results are presented in Table 4, and detailed results are described in the OSM. Most groups we compared did not differ, but people who were in same-gender and/or queer relationships (i.e., relationships that included two women, two men, or one or more trans/nonbinary people) reported higher rates of friends-first initiation than people who were in a relationship that included a man and a woman. Follow-up age analysis using data from Sample 7 also revealed that married adults under age 30 reported higher rates of friends-first initiation (84%) than married adults over age 30 (69%, χ2 = 8.51, [5.36%, 22.26%], p = .004). While friends-first initiation is highly prevalent in general, it may be even more prevalent among emerging adults and LGBTQ+ people.

Table 4.

Prevalence of Friends-First Initiation Among Various Demographic Groups.

| Sample(s) | Group Comparison | N | Friends-First Initiationa | χ2 | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2; 4–7 | Men | 545 | 67% | |||

| Women | 808 | 68% | 0.19 | [−3.5%, 5.56%] | .666 | |

| 2–7 | Students | 824 | 71% | |||

| MTurk workers | 1,013 | 68% | 1.92 | [−1.24%, 7.19%] | .166 | |

| 7 | Under age 40 | 342 | 73% | |||

| Over age 40 | 335 | 69% | 1.18 | [−3.06%, 10.62%] | .278 | |

| <29 | 90 | 84% | ||||

| 30–39 | 252 | 68% | ||||

| 40–49 | 200 | 65% | ||||

| 50+ | 135 | 75% | 13.72b | .003 | ||

| 4–7 | Women dating men | 1,470 | 68% | |||

| Same gender/Queer | 84 | 85% | 10.71 | [7.55%, 23.56%] | .001 | |

| 7 | BIPOC | 110 | 75% | |||

| White | 567 | 68% | 2.11 | [−2.59%, 15.17%] | .146 | |

| 7 | High school/some college | 179 | 65% | |||

| Bachelors/graduate | 487 | 70% | 1.52 | [−2.84%, 13.22%] | .218 |

Note. BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

a Weighted means for comparisons involving multiple samples. b Chi-squared test indicating that at least one age-group differed from the others; simple effects reported in text. Age was a categorical variable.

We also used data from Sample 7 to explore the prevalence of “friends-with-benefits” relationships among married friends-first initiators: Fully 42% reported that they had such a relationship with their future spouse, and this proportion is even higher among same-gender/queer couples (see the OSM).

Study 4

In our final study, we sought to address three questions about university students’ initiation experiences: (1) How long does the “friends” phase last in friends-first initiation? (2) Do people form friendships with the intention of pursuing friends-first initiation? and (3) Do people prefer friends-first initiation to other initiation strategies?

Method

Participants

All participants were from Sample 5 in Study 3. We aimed to recruit 300 participants with equal numbers of women and men, with the goal of retaining at least 250 participants to obtain a stable correlation estimate (Schonbrodt & Perugini, 2013). The original sample size was 310, but 12 were excluded for the following reasons: missing data for over 75% of the survey (n = 10), careless responding (i.e., nonsensical answers; n = 1), and duplicate survey (n = 1). The final sample comprised 298 introductory psychology students (50% women, 50% men; 57.4% single, 47.3% in a romantic relationship; age was not recorded due to technical error).

Measures

Friends-first initiators (n = 210) indicated how long they were friends prior to beginning a romantic relationship (converted to months) and selected from three options the one item that best described their intentions when forming the friendship (see Table 5 for response options). Finally, all participants (n = 298) selected from 12 options the one item that represented the best way to meet a potential dating partner (see Table 6 for response options). These questions were part of a survey that included other questions about relationship initiation that were unrelated to the current research goals.

Table 5.

Friends-First Initiation as an Intentional or Unintentional Relationship-Initiation Strategy in Study 4.

| Response Option | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Intentionally became friends with my past partner because I was attracted/romantically interested in [them] | 25 | 12.0 |

| (b) My partner intentionally became friends with me because [they were] attracted/romantically interested in me | 37 | 17.7 |

| (c) Neither (a) or (b), we just became friends and then became attracted/romantically interested after getting to know each other | 147 | 70.3 |

Note. One missing case from 210 participants who were friends first.

Table 6.

The Best Way to Meet a Dating or Romantic Partner According to Participants in Study 4.

| Response Option | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A friendship turning romantic | 139 | 47.4 |

| Through mutual friends | 53 | 18.1 |

| At school/university/college | 53 | 18.1 |

| At a social gathering (e.g., party) | 12 | 4.0 |

| At a place of worship/religious community | 10 | 3.4 |

| Through work | 7 | 2.3 |

| Through family connections | 7 | 2.3 |

| At a bar or social club | 4 | 1.3 |

| In an online community/social media | 2 | 0.7 |

| Through an online dating service | 1 | 0.3 |

| On a blind date | 1 | 0.3 |

| Other (please specify) | 4 | 1.3 |

We do not have consent to share participant data.

Results and Discussion

On average, friends-first initiators were friends for 21.90 months prior to becoming romantic partners (SD = 28.23; Mdn = 12; Mode = 12; range from 1 to 180 months). The length of these friendships stands in stark contrast to dating initiation, which typically occurs between relative strangers (e.g., Barelds & Barelds-Dijkstra, 2007). Furthermore, the vast majority of these university students did not enter into their friendships with romantic intentions or attraction (Table 5).

Moreover, almost half of the total sample thought that friends-first initiation was the best way to start a new romantic relationship (Table 6). Indeed, “a friendship turning romantic” was far and away the most popular method of relationship initiation among the options we presented. Thus, not only is friends-first initiation the most common type of initiation, but it is also a preferred method of initiation among university students.

General Discussion

Our results reveal that psychologists have largely overlooked the most prevalent and desirable form of relationship initiation. Even though two thirds of the nearly 1,900 participants in the studies that we meta-analyzed in Study 3 reported friends-first initiation, and even though 47% of the university age participants in Study 4 claimed that friends-first initiation is the best way to initiate a relationship, just 18% of the studies that we located in our literature search actually focused on this method of initiation. Notably, our impression is that many of these studies covered friends-first initiation in a brief or peripheral manner. Given the paucity of research on friends-first initiation, it is not surprising that the textbooks we coded only cited two articles that focused on friends-first research at all, and these works exclusively focused on friends-with-benefits relationships. This means that the field of close relationships has only a partial understanding of how romantic relationships actually begin.

There are certainly flaws in our research that should be addressed in future studies. Our research concerning the prevalence of friends-first initiation was based on retrospective reports. Such reports are easy to collect, but they can be biased by subsequent experience, and this threat to validity may be particularly salient for emotionally charged experiences like romance (Holmberg et al., 2004). Longitudinal, prospective studies may be better suited to studying friends-first initiation. In addition, although the samples we included in Study 3 lived in different regions of Canada and the United States and comprised both younger and older adults, our samples were still relatively WEIRD (i.e., Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, & Democratic; Henrich et al., 2010) and most samples did not include singles. Future research should examine cultural differences in the prevalence of friends-first initiation and other forms of initiation that may not be commonly recognized in the West, but which may be similarly overlooked by extant scientific theories and data. Further, although our analyses in Study 3 suggested that friends-first initiation is more common among same gender/queer couples than among couples that include a man and a woman—perhaps due to group differences in the size of the available dating pool, differing scripts concerning intimacy and communication, and fluid understandings of gender, among other reasons (e.g., Rose, 2000)—our sample size for the former group was very small (N = 84 across four samples; see the OSM), and we did not explicitly assess sexual orientation. Although our results are not definitive, they do support prior observations made about same-sex romantic relationship formation (Diamond, 2003). Nevertheless, future research examining the prevalence of various relationship-initiation strategies should include all sexual orientations. Research should also examine whether friends-first initiation is preferred among older adults, as our sample in Study 4 comprised university students. Finally, we did not define “friendship” for any of our participants, so our results may be biased by participants’ ability to self-define a relationship that lacks a precise and shared cultural definition to begin with (e.g., VanderDrift et al., 2016). Future research should seek to document the characteristics of friendships that do and do not lead to romance and to ensure that our prevalence rate is not potentially inflated by some participants’ excessively broad interpretation of friendship.

But to achieve these important goals and develop a science of relationship initiation that truly reflects people’s behavior, researchers may need to take a cold, hard look at the reasons why the field has overlooked friends-first initiation in the first place (and yes, we include ourselves in this critique). As we explained in the introduction, it is difficult to study social–psychological phenomena that occur spontaneously and in private, and it is easier to use experimental paradigms that enhance scientific control. Yet researchers’ preference for these methods may have shaped the very questions we think to ask, a kind of “tail wags the dog” situation that may have diverted attention away from friends-first initiation. Thus, researchers and funding agencies need to invest in more longitudinal studies that offer the possibility of capturing different types of relationship initiation as they spontaneously occur.

Moreover, as we explained in the introduction, implicit heterosexist biases hinder relationship science (Rose, 2000) and that may help to explain researchers’ relative neglect of friends-first initiation. For example, despite convincing evidence that passion-based intimacy can arise from friendship-based intimacy among same-gender friends (e.g., Diamond, 2003), it may not have occurred to researchers that such a thing could also happen in platonic friendships between heterosexual men and women. Moreover, if people assume that men and women cannot be platonic friends because sexual attraction inevitably gets in the way, and if researchers assume that everyone desires and prioritizes romantic relationships over friendships and singlehood (but see Bay-Cheng & Goodkind, 2016; Fisher & Sakaluk, 2020; Fisher et al., 2021), it may be difficult to conceive of the possibility that heterosexual men and women might maintain a platonic friendship for months or even years, like our Study 4 participants, before romantic feelings start to blossom. Interrogating and overcoming these and other heterosexist assumptions about relationships may be the first step to developing a science of relationship initiation that truly reflects the full diversity of human experience.

The gulf between the fields’ excessive scientific focus on dating initiation and people’s frequent lived experiences of friends-first initiation also has important implications for theories of relationship formation and maintenance. Researchers may need to revisit the validity of dominant models of relationship formation, including risk-regulation theory (Cameron et al., 2010; Stinson et al., 2015), sexual strategies theory (e.g., Eastwick et al., 2018), and assortative mating (e.g., Fletcher et al., 2000; Hoplock et al., 2019), all of which were devised by studying dating initiation, and all of which may apply differently, or not at all, to the process of friends-first initiation (see Hunt et al., 2015). Moreover, researchers should examine whether people exhibit systematic preferences for one type of initiation or another, and whether psychological variables like attachment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2020), sociosexuality (e.g., Gangestad & Simpson, 1990), life history (e.g., Belsky, 2012), or personality (e.g., McNulty, 2013) predict that preference. They may also need to examine whether these same variables moderate the success of each type of initiation, and whether such variables moderate the trajectory of relationships that form via dating or friends-first initiation. As such, studying friends-first initiation may be a fruitful enterprise that not only promises to expand extant theories of relationship initiation, but which also promises to shed light on new aspects of relationship initiation that could shift our understandings of how romantic relationships begin and progress.

Acknowledgments

We thank our coders, Janelle Lee, Will McPherson, Temilola Oloyede, and Michelle Paluszek and our many research assistants who helped collect the data that we meta-analyzed in Study 3.

Author Biographies

Danu Anthony Stinson is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Victoria, Canada. She studies the social self, with a focus on understanding how people navigate social scripts, including script violations, and cope with threats to belonging like rejection and social stigma.

Jessica J. Cameron is a professor of psychology at the University of Manitoba, Canada. She investigates the dynamic relationship between the self and interpersonal relationships, focusing on self-esteem, gender, and relationship initiation.

Lisa B. Hoplock earned her PhD in social psychology from the University of Victoria, Canada, and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Manitoba, Canada. She now works as a researcher in the technology sector.

Handling Editor: Jennifer Bosson

Note

For ease, we will use “gender” throughout the article, but we recognize the interdependent nature of gender and sex (gender/sex; see Cameron & Stinson, 2019; Hyde et al., 2018).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the inception and theoretical framing of this article. J. J. Cameron designed the studies and collected the majority of the data; D. A. Stinson helped to design and collected data for some of the samples included in the meta-analysis. L. B. Hoplock conducted most of the data analysis and constructed the supplemental materials. D. A. Stinson conducted some of the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was further edited by J. J. Cameron and L. B. Hoplock.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada Grant (435-2016-464) to J. J. Cameron.

ORCID iD: Danu Anthony Stinson  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1492-7133

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1492-7133

References

- Barelds D. P., Barelds-Dijkstra P. (2007). Love at first sight or friends first? Ties among partner personality trait similarity, relationship onset, relationship quality, and love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 479–496. 10.1177/0265407507079235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Cheng L., Goodkind S. A. (2016). Sex and the single (neoliberal) girl: Perspectives on being single among socioeconomically diverse young women. Sex Roles, 74, 181–194. 10.1007/s11199-015-0565-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. (2012). The development of human reproductive strategies: Progress and prospects. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 310–316. 10.1177/0963721412453588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D., Rubin D. C. (2004). Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 32(3), 427–442. 10.3758/BF03195836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E. (2010). Love in the fourth dimension. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 1–25. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson M. A., Levine T. R. (2009). Negotiating a friends with benefits relationship. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 66–73. 10.1007/s10508-007-9211-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleske-Rechek A., Somers E., Micke C., Erickson L., Matteson L., Stocco C., Schumacher B., Ritchie L. (2012). Benefit or burden? Attraction in cross-sex friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(5), 569–596. 10.1177/0265407512443611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury T. N., Karney B. R. (2019). Intimate relationships (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. J., Curry E. (2020). Gender roles and date context in hypothetical scripts for a woman and a man on a first date in the 21st century. Sex Roles, 82(5), 345–362. 10.1007/s11199-019-01056-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. J., Stinson D. A. (2019). Gender (mis)measurement: Guidelines for respecting gender diversity in psychological research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13, e12506. 10.1111/spc3.12506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. J., Stinson D. A., Gaetz R., Balchen S. (2010). Acceptance is in the eye of the beholder: Self-esteem and motivated perceptions of acceptance from the opposite sex. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(3), 513–529. 10.1037/a0018558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. J., Stinson D. A., Wood J. V. (2013). The bold and the bashful: Self-esteem, gender, and relationship initiation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(6), 685–691. 10.1177/1948550613476309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110(1), 173–192. 10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick P. W., Finkel E. J., Simpson J. A. (2019). Relationship trajectories: A meta-theoretical framework and theoretical applications. Psychological Inquiry, 30, 1–28. 10.1080/1047840X.2019.1577072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick P. W., Keneski E., Morgan T. A., McDonald M. A., Huang S. A. (2018). What do short-term and long-term relationships look like? Building the relationship coordination and strategic timing (ReCAST) model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(5), 747–781. https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/xge0000428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elodieunderglass. (2017, September 28). Starstarship asked: Maple and flannel. Tumblr. https://elodieunderglass.tumblr.com/post/165828759498/maple-and-flannel

- Fisher A. N., Sakaluk J. K. (2020). Are single people a stigmatized ‘group’? Evidence from examinations of social identity, entitativity, and perceived responsibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 86, 103844. 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A. N., Stinson D. A., Wood J. V., Holmes J. G., Cameron J. J. (2021). Singlehood and attunement of self-esteem to friendships. Social Psychological and Personality Science. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1948550620988460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fletcher G. J. O., Simpson J. A., Thomas G. (2000). Ideals, perceptions, and evaluations in early relationship development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 933–940. 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad S. W., Simpson J. A. (1990). Toward an evolutionary history of female sociosexual variation. Journal of Personality, 58(1), 69–96. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero L. K., Mongeau P. A. (2008). On becoming “more than friends”: The transition from friendship to romantic relationship. In Sprecher S., Wenzel A., Harvey J. (Eds.), Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 175–194). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halatsis P., Christakis N. (2009). The challenge of sexual attraction within heterosexuals’ cross-sex friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(6–7), 919–937. 10.1177/0265407509345650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza T. H., van Houwelingen H. C., Stijnen T. (2008). The binomial distribution of meta-analysis was preferred to model within-study variability. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(1), 41–51. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J., Heine S. J., Norenzayan A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg D., Orbuch T. L., Veroff J. (2004). Thrice told takes: Married couples tell their stories. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Hoplock L. B., Stinson D. A., Joordens C. T. (2019). “Is she really going out with him?”: Attractiveness exchange and commitment scripts for romantic relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 181–190. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L. L., Eastwick P. W., Finkel E. J. (2015). Leveling the playing field: Longer acquaintance predicts reduced assortative mating on attractiveness. Psychological Science, 26(7), 1046–1053. 10.1177/0956797615579273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J. S., Bigler R. S., Joel D., Tate C. C., van Anders S. M. (2018). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, 74(2), 171–193. 10.1037/amp0000307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D. L., Keys C. B. (1997). Sex and relationship variables as predictors of sexual attraction in cross-sex platonic friendships between young heterosexual adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0265407597142003 [Google Scholar]

- Laner M. R., Ventrone N. A. (2000). Dating scripts revisited. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 488–500. 10.1177/019251300021004004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machia L. V., Proulx M. L., Ioerger M., Lehmiller J. J. (2020). A longitudinal study of friends with benefits relationships. Personal Relationships, 27, 47–60. 10.1111/pere.12307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty J. K. (2013). Personality and relationships. In Simpson J. A., Campbell L. (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of close relationships (pp. 535–552). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R. (2020). Broaden-and-build effects of contextually boosting the sense of attachment security in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(1), 22–26. 10.1177/0963721419885997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. S. (2017). Intimate relationships (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Mongeau P. A., Knight K. (2015). Friends with benefits. In Berger C. R., Roloff M. E. (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication (Vol. 2, pp. 692–696). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rose S. (2000). Heterosexism and the study of women’s romantic and friend relationships. Journal of Social Issues, 56(2), 315–328. 10.1111/0022-4537.00168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H., Campbell C. (2012). Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 224–231. 10.1177/1948550611416520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schonbrodt F. D., Perugini M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47, 609–612. 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson D. A., Cameron J. J., Hoplock L. B., Hole C. (2015). Warming up and cooling down: Self-esteem and behavioral responses to social threat during relationship initiation. Self and Identity, 14(2), 189–213. 10.1080/15298868.2014.969301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanderDrift L. E., Agnew C. R., Besikci E. (2016). Friendship and romance. In Hojjat M., Moyer A. (Eds.), The psychology of friendship (pp. 109–122). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]