Abstract

Intraoperative fluorescence-based tumor imaging plays a crucial role in performing the oncological safe tumor resection with the advantage of differentiating tumor from normal tissues. However, the application of these fluorescence contrast agents in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was dramatically hammered as a result of lacking active targeting and poor retention time in tumor, which limited the Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) and narrowed the imaging window for complicated surgery. Herein, we reported an activated excretion-retarded tumor imaging (AERTI) strategy, which could be in situ activated with MMP-2 and self-assembled on the surface of tumor cells, thereby resulting in a promoted excretion-retarded effect with an extended tumor retention time and enhanced SNR. Briefly, the AERTI strategy could selectively recognize the Integrin αvβ3. Afterwards, the AERTI strategy would be activated and in situ assembled into nanofibrillar structure after specifically cleaved by MMP-2 upregulated in a variety of human tumors. We demonstrated that the AERTI strategy was successfully accumulated at the tumor sites in the 786-O and HepG2 xenograft models. More importantly, the modified modular design strategy obviously enhanced the SNR of AERTI strategy in the imaging of orthotopic RCC and HCC. Taken together, the results presented here undoubtedly confirmed the design and advantage of this AERTI strategy for the imaging of tumors in metabolic organs.

Keywords: Self-assembly, Biomaging, Peptide, Probe, Tumor

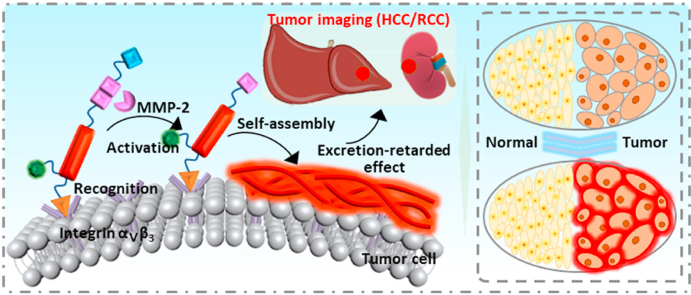

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Fluorescence-based tumor imaging plays a crucial role in performing the oncological safe tumor resection.

-

•

Self-assembled peptide possesses the advantage of active targeting and long-term retention time in tumor.

-

•

The activated excretion-retarded tumor imaging strategy extended the tumor retention time and enhanced SNR.

-

•

Assembly-mediated peptide probe successfully achieved the accurate identification of tumor boundaries and detection of minimal tumors (<2 mm).

1. Introduction

Surgical resection is still the foremost treatment for patients with solid tumor especially in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [[1], [2], [3]]. It is worth noting that, as vital metabolic organs, it is central to preserve the normal function of kidney and liver during tumor resection by reducing the excessively resected normal tissues. However, maximal resection of the tumor is crucial for achieving the long-term disease control in clinic [4,5], which efficiently limits the recurrence and progression of tumor. Taken together, the relationship between the extent of tumor resection and actual clinical benefit for the patient is predicated on the balance between cytoreduction and complications morbidity [1]. Therefore, it is of great significance to acquire adequate visualization of tumor boundaries in the medical surgery [6,7], which mainly depends on the surgeon level of experience or intraoperative frozen section analysis at present [8,9]. Nevertheless, the accuracy rate of diagnosing the cutting edge is a matter of debate (approximately 50%) [10], which significantly augmented the risk of tumor recurrence. Therefore, there is significant interest in developing novel tumor-specific molecular imaging agents for enhancing the tumor identification and guiding tumor resection. Based on the metabolism difference between tumors and normal tissues, 18F-FDG was designed for tumor detection before operation, which has achieved encouraging accomplishments through the combined use of PET/CT [11]. However, a variety of tumor types exhibit a non-specific difference to normal tissue on metabolism in the initial stage, which results in a lower detectable rate (50–65% for 18F-FDG) [12].

Intraoperative fluorescence-based tumor imaging have emerged as a promising methods in performing the oncological safe tumor resection with the advantage of real-time tumor localization, differentiating tumor from normal tissues and assessing the surgical cavity or the margins of the resected specimen [13,14]. Fluorescence contrast agents, as real-time tumor imaging probe to differentiate tumors from normal tissues, has been extensively applied in clinic to provide information on tumor detection and resection [15,16]. Thereinto, 5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) [17] and indocyanine green (ICG) [18,19], which were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has been used to mark the tumor cells in the image-guided surgery of a variety of tumors. However, the application of these fluorescence contrast agents in RCC and HCC was dramatically hammered as a result of lacking active targeting and poor retention time in tumor, which limited the Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) and lessened the imaging window for image-guided surgery [20,21]. To increase the SNR, plenty of fluorescently labeled tumor microenvironment-responsive molecular imaging agents were developed to increase the specificity [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. However, the traditional fluorescently labeled tumor-specific molecular imaging agents are prone to be quickly metabolized by the liver and kidney, which results in high background signal in the short-range and low fluorescence intensity in the long-range for the tumors in metabolic organs (liver and kidney). Therefore, the in vivo delivery of fluorescence contrast agents to the tumor sites has aroused wide concern [[26], [27], [28]]. As with drug delivery [29,30], fluorescence contrast agents need to be transported through circulation for specifically accumulation in tumor tissues for generating a high SNR and long-term retention [31].

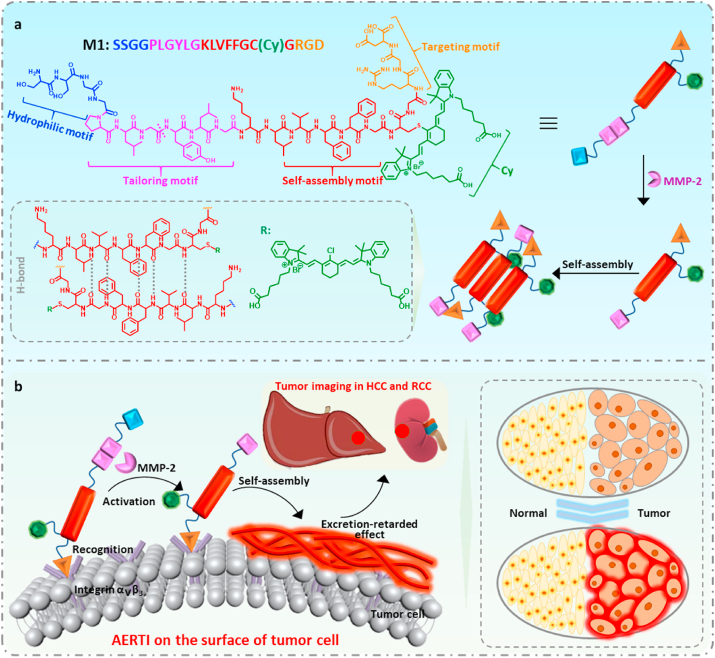

In our previous work, we have demonstrated the aggregation/assembly induced retention (AIR) effect [32] could significantly improve the delivery efficiency of fluorescence contrast agents by designing a near-infrared peptide probe for the image-guided surgery of renal cell carcinoma with a Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) of 2.5 [33], suggesting an encouraging method for high performance tumor imaging in the typical metabolic organs (Liver and kidney). In this work, we reported an activated excretion-retarded tumor imaging (AERTI) strategy, which could be in situ activated with MMP-2 and self-assembled on the surface of tumor cells, thereby leading to a promoted excretion-retarded effect with an extended tumor retention time and enhanced SNR. The tumor-selective recognition, MMP-2 activated self-assembly and excretion-retarded imaging process of AERTI was shown in Fig. 1. Initially, the AERTI could selectively recognize the Integrin αvβ3 overexpressed on the surface of tumor cells [34,35]. Afterwards, the AERTI would be activated and in situ assembled into nanofibrillar structure after specifically cleaved by MMP-2 upregulated in a variety of human tumors (Fig. 1a) [36,37]. Owing to this nanofibrillar structure constructed on the surface of tumor cells, high performance excretion-retarded imaging of tumor in the metabolism organs of was achieved (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the activated excretion-retarded tumor imaging (AERTI) strategy. (a) The AERTI strategy consists of (i) RGD, as Integrin αvβ3-targeting motif, (ii) PLGYLG, as MMP-2-cleavage peptide linker, (iii) KLVFFGC, as canonical self-assembly motif, (iv) Cy, as signaling molecular, (v) SSGG, as hydrophilic motif. Upon MMP-2 specific enzymatic cleavage, the remaining molecule is triggered to form nanofibril conformation of antiparallel β-sheet. (b) Mechanism of action of AETRI strategy highlight tumor-selectively recognition, enzymatic activation, and excretion-retarded effect.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All amino acids and Wang resin were bought from Gill Biochemical (Shanghai, China). The medicines, reagents, and solvents used in the experiment were all purchased from commercial companies. 786-O, HepG2 and HUVEC cell lines were derived from the Cell Culture Center of the Institute of Basic Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). Female BALB/c nude mice at approximately 6–8 weeks old were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. Molecule synthesis and characterization of AERTI

Experiments used peptide P1 (SSGGPLGYLGKLVFFGCGRGD), P2 (SSGGPGLGYLKLVFFGCGRGD) and R–P1 (YLGKLVFFGCGRGD) were bought from GL Biochem (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The molecular weight and purity of the P1, P2 and R–P1 were characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The synthesis method of Cyanine Dye (Cy7-Cl) labeled P1, P2 and R–P1 was as follows: Peptide and the fluorescent molecules were placed in Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 8.4). After reacting for 2 h, the reaction product is processed with desalination and dialysis. The Excess fluorescent molecules in the solution are removed by dichloromethane. Finally, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was used for characterizing the molecular weight of M1 (SSGGPLGYLGKLVFFGC(Cy)GRGD), M2 (SSGGPGLGYLKLVFFGC(Cy)GRGD) and R-M1 (YLGKLVFFGC(Cy)GRGD). Additionally, the Cyanine Dye (Cy7-Cl) was provided by Dr Wu-Yi Xiao, Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, CAS. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.3. Turbidity measurement of AERTI

Firstly, samples M1, M2 and R-M1 were dissolved with DMSO to obtain the mother liquor sample in a high concentration (5 mM) and stored at room temperature. Before measurement, the 5 mM sample was diluted 100 times with water solvent Next, the sample was put into UV-2600 UV-VIS spectrophotometer to measure the absorbance of at 600 nm. Finally, the condition that needed to be maintained during measurement was that it was stirred every 5 s while recording data and the measurement duration was 90 min. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.4. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy of AERTI

At room temperature, samples M1 (10 μM), M2 (10 μM) and R-M1 (10 μM) was scanned by a CD spectrometer by using a cell pathlength condition. In the working state, the scanning speed of the instrument was set to 1200 nm min−1. Finally, the resolution was specified as 1 nm. The solution background was subtracted for the purpose of correcting the spectrum. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.5. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of AERTI

Before measurement, a simple pretreatment of M1 (50 μM), M2 (50 μM) and R-M1 (50 μM) samples was required by waiting 7 d in deionized water solvent to ensure it stable and self-assembled sufficiently. Next, freeze-drying was used to convert the physical state of the sample from solution to powder. Sample preparation: The powdered sample and the dehydrated KBr crystals were mixed and compressed into granules. Finally, the samples were analyzed using spotlight 200i, Perkin Elmer Instruments Co., Ltd. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of AERTI

The samples of M1, M2 and R-M1 were observed using TEM. Firstly, sample must reached the assembled state in the assembled condition 1 mM of acetonitrile: H2O = 2:3 mixed solvent dissolved. After being stored for 7 d, the sample was fully self-assembled and then subjected to TEM operation. Next, 10 μL of sample solution was placed on the carbon-coated copper mesh. 5 min later, the excess solution on the copper mesh was absorbed by the filter paper. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.7. Cytotoxicity assay of AERTI

The 786-O and HepG2 cell lines were used to assess the cytotoxicity of AERTI, respectively. Next, 786-O and HepG2 cells were seeded onto 96 well plates at a density of 5 × 103 each well and incubated overnight until the cells were completely adhered. Afterwards, a high concentration of M1 and M2 in DMSO mother solution was diluted to obtain solutions of different concentrations and ensure DMSO concentration less than 1%, followed by incubation with the cells for 24 h. The cell viability rate was calculated as (Sample wells (As)-Blank wells (Ab))/(Control wells (Ac)-Blank wells (Ab)) × 100%. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.8. In vitro signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) of AERTI for tumor imaging

786-O and HUVEC cell lines were used for calculating the in vitro SNR of AERTI for tumor imaging. Firstly, the 786-O and HUVEC cells were seeded onto 96 well plates at a density of 5 × 103 each well and incubated overnight until the cells were completely adhered. Next, the M1 and M2 (20 μM) samples were incubated with the cells for 4 h to make sure the self-assembly of AERTI. After washed with PBS for 3 times the fluorescence images of 786-O and HUVEC cells were observed with in vivo fluorescence imaging system (IVIS). All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.9. In vitro photostability of AERTI for tumor imaging

786-O cell lines were used for envaluating the in vitro photostability of AERTI for tumor imaging. Firstly, the 786-O cells were seeded onto 96 well plates at a density of 5 × 103 each well and incubated overnight until the cells were completely adhered. Next, the M1 and M2 (20 μM) samples were incubated with the cells for 4 h to make sure the self-assembly of AERTI. After washed with PBS for 3 times and irradiated with NIR laser (0, 0.45, 0.90, 1.35, 1.80, 2.25, 2.70, 3.15 and 3.60 kJ/cm2, respectively and the distance between the light source and the sample was 1 cm), the fluorescence images of 786-O cells were observed with in vivo fluorescence imaging system (IVIS). All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.10. Cellular imaging experiment of AERTI

786-O cell lines overexpressed with interin αvβ3 were used for cellular imaging experiments. Firstly, the 786-O cells were seeded onto confocal microscopy culture dishes at a density of 2 × 105 cells and incubated overnight until the cells were completely adhered. Next, the M1 and M2 (20 μM) samples were incubated with the cells for 15 min. Next, the fluorescence images of 786-O cells were observed under a 40× objective. Finally, the fluorescence intensity was measured by Volocity software. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.11. In vivo fluorescence imaging of AERTI

All the animal experiments were approved by the Committee for Animal Research of the National Center for Nanoscience and Technology (NCNST21-2011-0602). Firstly, A density of 5 × 106 786-O/HepG2 cells in PBS solution were subcutaneously injected into the right hind of mice to construct the 786-O/HepG2 xenograft models. When the tumor volume grew up to approximately 200 mm3, the mice were administrated with M1 (200 μM, 200 μL) and M2 (200 μM, 200 μL) for in vivo fluorescence imaging at different timepoints using a Maestro IVIS (CRi, Woburn, MA, USA). Finally, the major organs and tumors of 786-O xenograft mice were collected to investigate the biodistribution of AERTI. All the experiments were independently repeated for 3 times.

2.12. Establishment of orthotopic RCC xenograft models

Initially, the mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized and placed in a lateral position. Afterwards, under sterile conditions, the skin and body wall were opened along the dorsal midline. Subsequently, the left kidney was pushed out through the incision. Next, 5 × 106 786-O cells resuspended in 15 μL Matrigel were injected into the surface of kidney with a 29 G needle. After a bulla was observed, the kidney was returned into abdomen with incisions closed successively. Finally, the tumor growth in kidney was confirmed with IVIS after intraperitoneally injection of luciferin for 10 min. Additionally, the mice were administrated with M1 (200 μM, 200 μL) and M2 (200 μM, 200 μL) for in vivo fluorescence imaging.

2.13. Establishment of orthotopic HCC xenograft models

Initially, the mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized and placed in a dorsal position. Afterwards, under sterile conditions, the skin and body wall were opened along the left lower costal margin. Subsequently, the liver was pushed out through the incision. Next, 5 × 106 HepG2 cells in 15 μL Matrigel were injected into the surface of liver with a 29 G needle. After a bulla was observed below the capsule, the liver was returned into abdomen with incisions closed successively. Finally, the tumor growth in liver was confirmed with IVIS after intraperitoneally injection of luciferin for 10 min. Additionally, the mice were administrated with M1 (200 μM, 200 μL) and M2 (200 μM, 200 μL) for in vivo fluorescence imaging.

2.14. Toxicology evaluation of AERTI

The major organs and serum of mice (n = 4) were collected after treatment with PBS and M1 (200 μM, 200 μL) for 1 d, 7 d and 14 d. Subsequently, the histology evaluation was conducted by Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd. Meanwhile, the blood biochemistry analyze was carried out with Hitachi Automatic Biochemical Analyzer 7100. All the experiments were independently repeated for 6 times.

2.15. Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the result was performed with one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Self-assembly and fibrillar transformation

The modularized units of the AERTI consist of five functional modules: (i) RGD, acts as targeting motif which selectively recognize Integrin αvβ3 overexpressing tumor cells, (ii) PLGYLG, behaves as MMP-2 enzyme sensitive linker segment for cleavage [33], (iii) KLVFFGCG, as canonical self-assembly motif [38], (iv) Cy, as fluorescent probe and (v) SSGG, the hydrophilic motif to modulate molecular solubility. The five abovementioned modules were sequentially conjugated to form AERTI (Figs. S1–S6). In the first place, investigation of structure-relevant self-assembly behavior of AETRI was conducted using experiment molecule, named as molecule 1 (M1, SSGGPLGYLGKLVFFGC(Cy)GRGD) with enzyme-responsive peptide linker and self-assembly motif was designed, synthesized and characterized (Figs. S1–S6). Secondly, to elucidate the importance of PLGYLG module, the control molecule 2 (M2, SSGGPGLGYLKLVFFGC(Cy)GRGD) possessing only self-assembly motif were designed, synthesized and characterized (Figs. S1–S6). Moreover, as self-assembly module was hypothesized to play a key role for molecular imaging, a cleaved version of M1, named as R-M1 (YLGKLVFFGC(Cy)GRGD) was designed, synthesized and characterized similarly. The M1, R-M1and M2 was characterized with high resolutions MS, ESI-MS and HPLC (Figs. S1–S6).

Schematic illustration of the MMP-2 activated self-assembly behaviors of AERTI (Fig. 2a). Firstly, in order to verify the enzyme responsiveness of M1, the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to monitor the formation of cleavage motif R-M1. As a result, the peak of M1 was vanished after incubated with MMP-2 with a retention time at 16.8 min. Meanwhile, two new peaks were for SSGGPLG at 13.5 min and R-M1 at 15.2 min, respectively (Fig. S7). Next, the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) of R-M1 to form nanofibers was investigated with the fluorescence probe (ANS), which demonstrated to be 4.4 μM (Fig. S8). Then, turbidity assay was carried out to examine MMP-2 mediated self-assembly behavior of molecule M1. It was observed than the turbidity readout of R-M1 experienced significant escalation initially and reached plateau at approximately 60 min in deionized water system at 37 °C (Fig. 2b), which verified the occurrence of self-assembly process of R-M1. Similar results were observed in the turbidity assay of M1+MMP-2 (Fig. S9). On contrary, indiscernible change of turbidity value was observed regarding M1 and M2 (Fig. 2b), which remains in homogenous monomeric state under same condition. Together, these data suggested that molecule cleavage by MMP-2 plays a key role in triggering the self-assembly progress of M1. Next, Fluorescent probes thioflavin T (ThT) and 1-anilino-8-naphthalene sulfonate (ANS), which could selectively bind to the amyloid fibrils, were used to study the β-sheet formation of M1 after MMP-2 cleavage. As expected, the fluorescence intensity of R-M1 was obviously increased compared with that of M1 and M2 group (Fig. S10), further demonstrating the β-sheet formation of M1 after MMP-2 cleavage. In addition, circular dichroism (CD) spectrometry and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum were conducted to characterize the secondary structure of M1 cleaved by MMP-2 enzyme. It was recorded that strong positive Cotton effect at approximately 200 nm plus weak negative Cotton effect at 216 nm were visible in R-M1 group, as a confirmatory sign of the formation of β-sheet structure in R-M1 (Fig. 2c). On the contrary, the M1 and M2 had a formation of random coiled secondary structure in the light of the strong negative Cotton effect at about 202 nm in the CD spectrum. Moreover, the formation of β-sheet structure was further confirmed based on the band at 1631 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum. Meanwhile, the band at 1641 cm−1 without blue shift indicated the amide I band without other second structure (Fig. 2d). These results, altogether, demonstrated the formation of β-sheet structure in M1 after MMP-2 cleavage. Finally, the morphology of M1 after MMP-2 cleavage was investigated with the transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As a result, the R-M1 self-assembled into short and thick nanofibers with a diameter of 13.4 ± 3.1 nm (Fig. 2e and Fig. S11). Additionally, the M1+MMP-2 also self-assembled into nanofibers with a diameter of 12.3 ± 2.4 nm (Fig. S12). Altogether, it can be concluded that the M1 can be cleaved by MMP-2 to release the R-M1, which can form nanofibers by intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Moreover, the absorption (Fig. S13) and fluorescence spectra of M1 before and after cleaved by MMP-2 demonstrated that there is little quenching effect was occurred for M1 after cleaved by MMP-2 (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2.

Self-assembly process of AERTI in solutions. (a) Schematic illustration of AERTI strategy leveraging MMP-2 activated self-assembly mechanism. (b) Turbidity assay for M1, R-M1 and M2. (c) CD spectra of M1, R-M1 and M2 in deionized water system. (d) FTIR spectra of monomeric M1, M2 and assembled R-M1. (e) TEM image showed self-assembled β-sheet nanofibrous conformation of R-M1 (50 μM) in acetonitrile: H2O = 2:3 mixed solution for 1 week. Scale bar = 100 nm. (f) The fluorescence spectra of M1, M2 and M1+MMP-2.

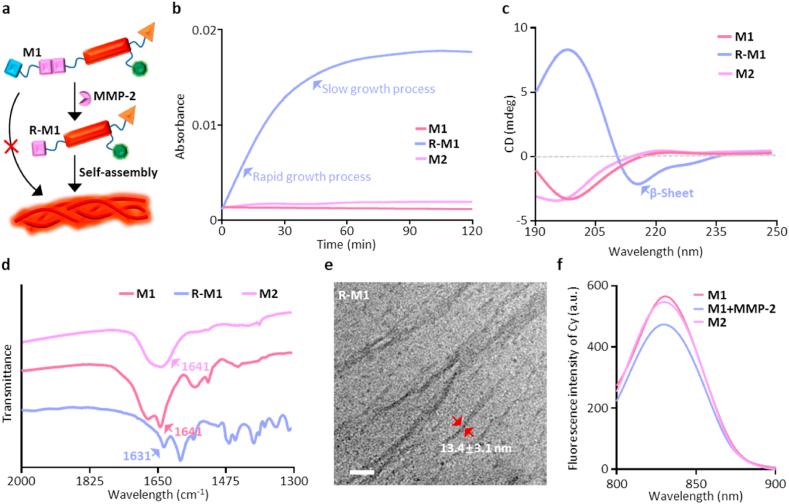

3.2. In vitro tumor targeting and extracellular morphological characterization of AERTI

Further, to study the in vitro Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) of AERTI for tumor imaging, 786-O and HUVEC cells were incubated with M1 and M2 for 4 h at 37 °C in a 96-Well plate for fluorescence imaging (Fig. 3a). As a result, the 786-O cells showed much higher fluorescence intensity in M1-treated wells compared with that in HUVEC cells. Meanwhile, a moderate fluorescence intensity was observed in the M1-treated wells. Moreover, statistical analysis indicated that the M1 exhibited significantly higher SNR of 2.8 for tumor imaging than that of 2.1 in the M2-treated groups (Fig. 3b), indicating that M1 had advantages of higher SNR for tumor imaging over M2 owing to the stable β-sheet structured fibrous networks. Mountains of evidence have demonstrated that the β-sheet structure-enriched nanofibers could efficiently prevent the radiationless internal conversion (IC), isomerization and degradation of fluorescence molecule through bounding and locking the Cy dye in hydrophobic domains. Therefore, the in vitro photostability of AERTI, as an important indicator of tumor imaging, was further investigated after co-incubated with 786-O cells for 4 h at 37 °C (Fig. 3c). As a result, the photostability of Cy in the M1 was significantly increased with only 55% photobleaching observed (Fig. 3d). In contrast, M2 showed 81% photobleaching after irradiation for 40 min. The photodegradation rate of Cy in M1 was decreased by 26% than that of Cy in M2, demonstrating that the enhanced photostability was attributed to the MMP-2-cleavage self-assembly of AERTI. Moreover, AERTI was demonstrated to be distributed on the membrane of 786-O cells after incubated with M1 for 15 min at 37 °C, which exhibited an enhanced tumor retention time compared with that of M2 (Fig. 3e and Fig. S14). Subsequently, to observe the nanofibrillar networks on the membrane of tumor cells, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was utilized to observe the morphology of AERTI. Expectedly, the presence of nanofibrillar networks were clearly observed on the surface of 786-O cells treated with M1 (Fig. 3f and Fig. S15). In contrast, no nanofibrillar structure was detected on the membrane of PBS 786-O cells (Fig. 3f). Additionally, no impact was observed on the cell viability of 786-O and HepG2 when treated with M1 and M2, indicating the good biocompatibility of AERTI (Fig. 3j and Fig. S16).

Fig. 3.

Tumor-selectively recognition and MMP-2 activated self-assembly behavior of AERTI in vitro. (a) Representative NIR fluorescence images of 786-O cells and HUVEC cells after treatment with M1 and M2 (20 μM), respectively. (b) Statistical analyses of the Signal to Noise Ratio of M1 and M2, respectively. (c) Photostability evaluation of M1 and M2 (20 μM) under near-infrared laser irradiation for 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 min. (d) Statistical analyses of the photostability of M1 and M2, respectively. (e) Representative confocal images of time-dependent monitoring of 786-O cells treated with the M1 (20 μM) followed by washing with PBS and replacing the medium. Scale bar = 20 μm. (f) Representative SEM images of 786-O cells after treated with PBS (left, without self-assembled β-sheet nanofibers) and M1 (right, with self-assembled β-sheet nanofibers) (20 μM). Scale bar = 3 μm. Scale bar = 500 nm (Zoom in). (j) Cell viability assay of 786-O cells treated with M1 and M2 for 24 h ***p < 0.001.

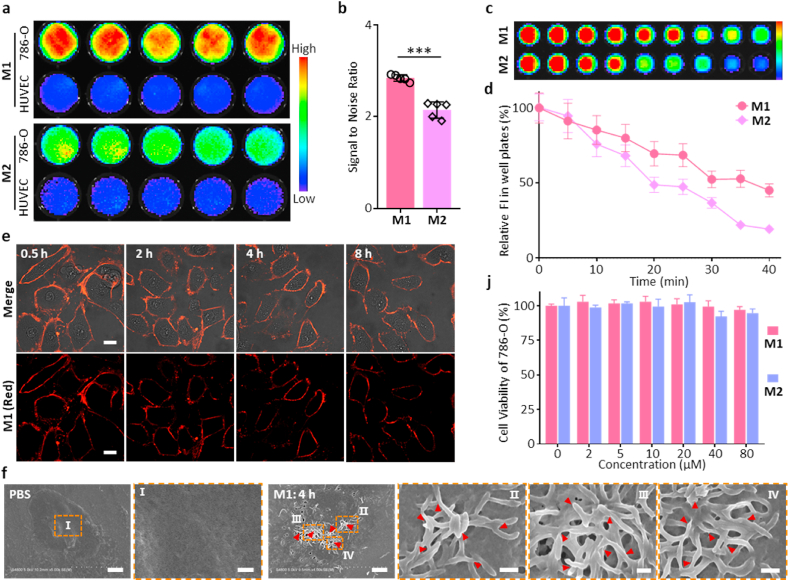

3.3. In vivo specific tumor accumulation and enhanced imaging time window of AERTI in RCC and HCC xenograft model

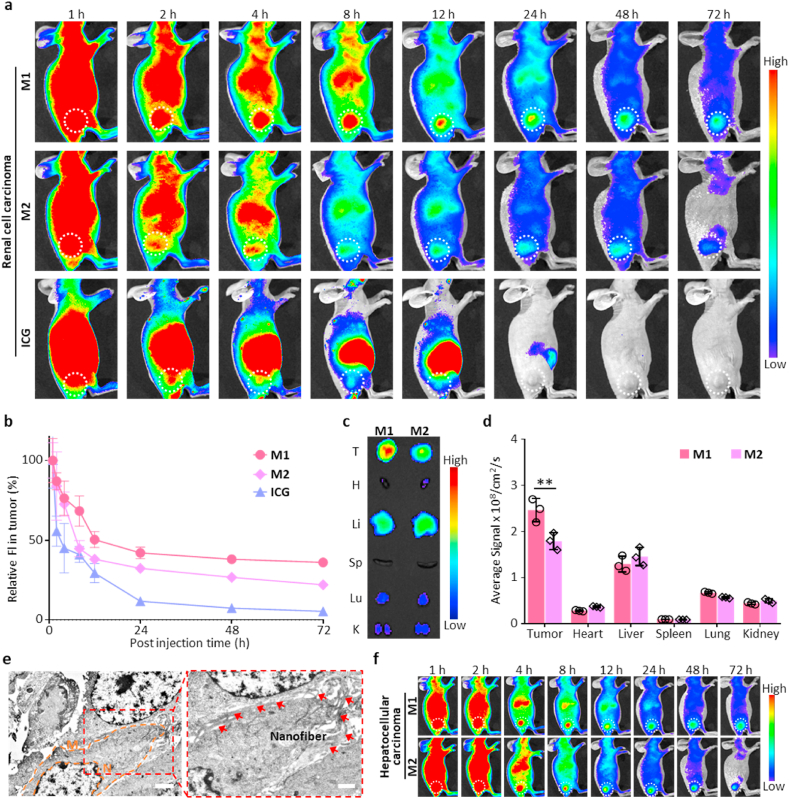

To confirm the specific tumor accumulation and evaluate the imaging time window, the persistence of AERTI in the tumor sites was evaluated by intravenously injecting the M1 and M2 into 786-O (Renal Cell Carcinoma, RCC) xenograft mice, respectively. Representative fluorescence images of the 786-O xenograft mice were successively collected at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h (Fig. 4a). As a result, the mice in M1-treated group exhibited an approximately identical fluorescence at the tumor site within 1 h compared with that in M2-treated group, indicating that M1 and M2 hold the same targeting ability owing to the RGD motif. Furthermore, AERTI was observed to be continuously accumulated at the tumor site and persisted for 72 h according to the statistical analyses results. By contrast, the fluorescence of M2 at the tumor site quickly decreased after 4 h and nearly vanished at 72 h, indicating that the M1-treated group exhibited a significantly higher fluorescence intensity in the tumors than that in the M2-treated groups from 2 to 72 h post-injection (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these results demonstrated that AERTI strategy had advantages of long-time retention in tumors over M2 owing to the in vivo self-assembly based stable β-sheet structured fibrous networks. Additionally, the biodistribution of AERTI strategy was further investigated through collecting the tumors together with major organs of 786-O xenograft mice for ex vivo fluorescence imaging after administered with M1 and M2 for 24 h. As a result, strong fluorescence signals were detected on the tumors compared with other organs (Fig. 4c and d), suggesting that the M1 were effectively accumulated to the tumor tissues. Moreover, nanofibrous structures were clearly observed on the surface of tumor cells from representative Bio-TEM images after administration of M1, which possibly attributed to MMP-2 activated in vivo self-assembly of M1 (Fig. 4e). More importantly, the specific tumor accumulation and imaging time window of AERTI was further evaluated by intravenously injecting the M1 and M2 into HepG2 (Hepatocellular Carcinoma, HCC) xenograft mice. As expected, AERTI was observed to be continuously accumulated at the tumor site and persisted for 72 h. In addition, the fluorescence signals at tumor sites in M1-treated group exhibited a significantly higher fluorescence intensity than that in the M2-treated groups from 2 to 72 h post-injection based on the representative fluorescence images of mice at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h post-injection (Fig. 4f and Fig. S17). These results further demonstrated the specific tumor accumulation and enhanced imaging time window of AERTI strategy for the image-guided surgery of RCC and HCC.

Fig. 4.

In vivo verification of the tumor-selectively accumulation and retention of AERTI strategy. (a) Representative fluorescence images of 786-O xenograft mice after intravenous injection of M1, M2 and ICG (200 μM, 200 μL) (n = 3). (b) Corresponding statistical analyses of the fluorescence intensity at the tumor site. (c)Ex vivo fluorescence images of tumor and major organs collected after intravenous administration of M1 and M2 (200 μM, 200 μL) for 24 h, respectively (n = 3). (d) Corresponding statistical analyses for the biodistribution of M1 and M2 in tumor and major organs (heart (H), liver (Li), spleen (Sp), lung (Lu) and kidney (K)) (n = 3). (e) Representative Bio-TEM results of the in situ self-assembled β-sheet nanofibers after administration of M1 (200 μM, 200 μL). Scale bar = 2 μm (Left), Scale bar = 1 μm (Right). (f) Representative near-infrared fluorescence images of HepG2 xenograft mice after intravenous injection of M1 and M2 (200 μM, 200 μL) (n = 3). **p < 0.01.

3.4. In vivo tumor-imaging SNR of AERTI in orthotopic RCC and HCC xenograft model

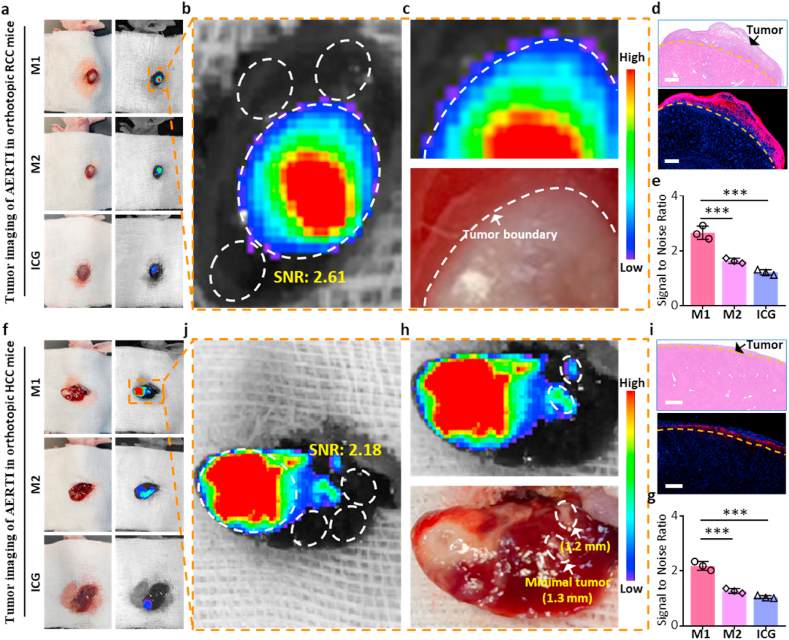

Encouraged by the results above, the orthotopic RCC and HCC xenograft mice was successfully constructed to investigate the SNR of AERTI in the tumor fluorescence imaging towards metabolism organs. Initially, the tumor-bearing kidney was pushed out and exposed through the incision along the dorsal midline after intravenous injection of M1 and M2 for 24 h, respectively. Moreover, representative bright field image and fluorescence image of the tumor-bearing liver from orthotopic RCC xenograft mice were captured, respectively (Fig. 5a). The regions of interest (ROI) from tumor and normal tissues used for calculating the SNR were labeled in Fig. 5b. As a result, the SNR of AERTI for RCC imaging was calculated as 2.61 according to the fluorescence intensity in ROI of orthotopic RCC xenograft mice (Fig. 5a). More importantly, the tumor boundary was precisely identified in the fluorescence imaging results of AERTI owing to the enhanced SNR, which was strictly in accordance with the tumor margin identified by bright field results (Fig. 5c), which is of great significance for the image-guided surgery of RCC. Additionally, the tumor boundary identified with fluorescence imaging results of AERTI was similar to the results in corresponding histological results (Fig. 5d). Statistical analyses of the SNR of M1, M2 and ICG for RCC imaging was shown in Fig. 5e, respectively. Subsequently, the tumor-bearing liver was pushed out and exposed through the incision at the left lower costal margin after intravenous injection of M1 and M2, respectively. Moreover, representative bright field image and fluorescence image of the tumor-bearing liver from orthotopic HCC xenograft mice were captured, respectively (Fig. 5f). The regions of interest (ROI) from tumor and normal tissues used for calculating the SNR were labeled in Fig. 5j. As a result, the SNR of AERTI for HCC imaging was calculated as 2.18 according to the fluorescence intensity in ROI of orthotopic HCC xenograft mice at 24 h post-injection. Meanwhile, the minimal tumors (<2 mm) were successfully detected by the fluorescence imaging results of AERTI owing to the enhanced SNR (Fig. 5h), which is of great significance for the image-guided surgery of HCC. Additionally, the tumor boundary identified with fluorescence imaging results of AERTI was quite similar to the results in corresponding histological results (Fig. 5i). Statistical analyses of the SNR of M1, M2 and ICG for RCC imaging was shown in Fig. 5g, respectively. These data together evidently demonstrated that AERTI strategy possess the advantages in achieving accurate detection of the tumor boundaries and detection of minimal tumors (<2 mm) with enhanced SNR, which showed a prodigious potential in the image-guided surgery of the tumors in metabolic organs (liver and kidney).

Fig. 5.

In vivo evaluation for the SNR in tumor imaging of AERTI strategy. (a) Representative fluorescence images of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after intravenous administration with M1, M2 and ICG (200 μM, 200 μL) in the orthotopic RCC xenograft mice at 24 h post injection (n = 3). (b) The region of tumor tissue and normal tissue which was used for calculating SNR ratio of M1 was labeled with wight circle. (c) Representative images of the tumor boundary identified by naked eyes and fluorescence imaging results. (d) Representative images of the tumor boundary identified by H&E results and fluorescence microscopy imaging results. Scale bar = 500 μm. (e) Statistical analyses of the Signal to Noise Ratio of M1, M2 and ICG, respectively. (f) Representative fluorescence images of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after intravenous administration with M1 and M2 (200 μM, 200 μL) in the orthotopic HCC xenograft mice at 24 h post injection (n = 3). (j) The region of tumor tissue and normal tissue which was used for calculating SNR ratio of M1 was labeled with wight circle. (h) Representative images of the tumor boundary identified by naked eyes and fluorescence imaging results. (i) Representative images of the tumor boundary identified by H&E results and fluorescence microscopy imaging results. Scale bar = 500 μm. (g) Statistical analyses of the Signal to Noise Ratio of M1, M2 and ICG, respectively.

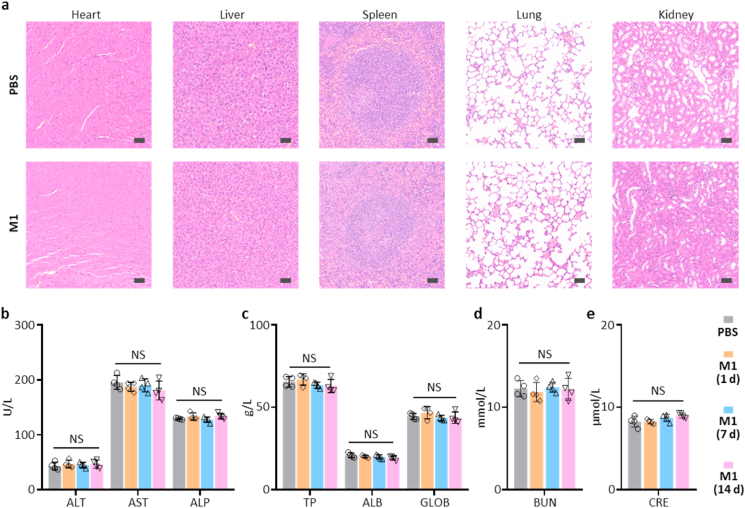

3.5. In vivo side effects of AERTI strategy

Finally, to further study the potential in vivo adverse effects of AERTI, the major organs and serum of healthy mice were harvested after intravenous administrated with PBS and M1 respectively. As a result, the representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images exhibited no histological differences were detected in major organs at 1 d post-injection (Fig. 6a), suggesting no notable toxicity of AERTI. More importantly, the results of blood biochemistry analyses at 1 d, 7 d and 14 d post-injection exhibited no noticeable difference was observed between PBS and M1 treatment group regarding liver function index, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (Fig. 6b), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), and globulin (GLOB) (Fig. 6c). Meanwhile, no noticeable difference was observed between PBS and M1 treatment group regarding renal function indicators including blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (Fig. 6d) and creatinine (CRE) levels (Fig. 6e). These results altogether suggested the good biosafety of AERTI for clinical translational application.

Fig. 6.

In vivo safety profile of AERTI strategy. (a) Histology evaluation of the major organs after treatment with PBS and M1 (200 μM, 200 μL) for 1 d (n = 4). Scale bar = 50 μm. (b–e) Blood biochemistry data of the mice after treatment with PBS and M1 (200 μM, 200 μL) for 1 d, 7 d and 14 d (n = 4). NS means no significance.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed an activated excretion-retarded tumor imaging (AERTI) strategy, which could be in situ activated with MMP-2 and self-assembled on the surface of tumor cells, thereby resulting in a promoted excretion-retarded effect with an extended tumor retention time and enhanced SNR. Briefly, the AERTI could selectively recognize the Integrin αvβ3, which was demonstrated to be upregulated on the membrane of tumor cells. Afterwards, the AERTI would be activated and in situ assembled into nanofibrillar structure after specifically cleaved by MMP-2 upregulated in a variety of human tumors. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the AERTI was successfully accumulated at the tumor sites in the 786-O and HepG2 xenograft models with a tumor retention time up to 72 h. More importantly, the modified modular design strategy obviously enhanced the SNR of AERTI in the tumor imaging of orthotopic RCC and HCC xenograft mice. Consequently, an accurate identification of the tumor boundaries and detection of minimal tumors (<2 mm) were successfully achieved, which is of crucial significance for the image-guided surgery of RCC and HCC. Taken together, all the results above undoubtedly confirmed the design and advantage of this AERTI strategy for the imaging of tumors in metabolic organs.

For the side effects of AERTI strategy: Different from low molecular weight drugs, the aggregation, polymerization, or assembly of biomaterials can provoke unwanted and unpredictable immunogenicity which can lead to serious and life-threatening side-effects. Fortunately, compared with antibody the benefit of peptide is the low immunogenicity. Moreover, for peptide-based self-assembled β-sheet fibrillar biomaterials, previous reports have demonstrated minimal inflammatory and immune responses in vivo. Despite, it's still crucial for the peptide-based biomaterials in elucidating the important risk factors which might lead to immunogenicity before clinical translational application. As for the aggregation of peptides in the lumen of the capillaries which could be potentially unsafe for patients, AERTI strategy was designed to be in situ activated with MMP-2 and self-assembled on the surface of tumor cells. And MMP-2 was demonstrated to be crucial for triggering the self-assembly of M1. Despite, AERTI strategy would targeting the αvβ3 in the lumen of the capillaries (low expression of MMP-2), the M1 molecule can maintain in a monomer state without MMP-2. Therefore, it's convinced that our AERTI strategy was biosafety for application owing to the quick clearance of monomer peptides molecular.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to be declared.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Da-Yong Hou: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Project administration. Man-Di Wang: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Xing-Jie Hu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Investigation. Zhi-Jia Wang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Methodology. Ni-Yuan Zhang: Experimental design, Investigation, Data curation. Gan-Tian Lv: Software, Visualization. Jia-Qi Wang: Formal analysis, Investigation. Xiu-Hai Wu: Software, Visualization. Hao Wang: Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Wanhai Xu: Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Regional Key Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20385), National Natural Science Foundation of China (51725302, 52003270).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.12.003.

Contributor Information

Hao Wang, Email: wanghao@nanoctr.cn.

Wanhai Xu, Email: xuwanhai@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sanai N., Berger M.S. Surgical oncology for gliomas: the state of the art. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:112–125. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiller J.G., Perry N.J., Poulogiannis G., Riedel B., Sloan E.K. Perioperative events influence cancer recurrence risk after surgery. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:205–218. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang F., Tie Y., Tu C., Wei X. Surgical trauma-induced immunosuppression in cancer: recent advances and the potential therapies. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020;10:199–223. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wainwright J.V., Endo T., Cooper J.B., Tominaga T., Schmidt M.H. The role of 5-aminolevulinic acid in spinal tumor surgery: a review. J. Neuro Oncol. 2019;141:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-03080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turcotte E.L., Rahme R.J., Merrill S.A., Hess R.A., Lettieri S.C., Bendok B.R. The utility of 5-aminolevulinic acid for microsurgical resection of meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:343. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilewskie M., Morrow M. Margins in breast cancer: how much is enough? Cancer. 2018;124:1335–1341. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha S.W., Sohn J.H., Kim S.H., Kim Y.T., Kang S.H., Cho M.Y., Kim M.Y., Baik S.K. Interaction between the tumor microenvironment and resection margin in different gross types of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;35:648–653. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko S., Chun Y.K., Kang S.S., Hur M.H. The usefulness of intraoperative circumferential frozen-section analysis of lumpectomy margins in breast-conserving surgery. J. Breast Cancer. 2017;20:176–182. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2017.20.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallick R., Stevens T.M., Winokur T.S., Asban A., Wang T.N., Lindeman B.M., Porterfield J.R., Chen H. Is frozen-section analysis during thyroid operation useful in the era of molecular testing? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019;228:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hekman M.C.H., Rijpkema M., Langenhuijsen J.F., Boerman O.C., Oosterwijk E., Mulders P.F.A. Intraoperative imaging techniques to support complete tumor resection in partial nephrectomy. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2018;4:960–968. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Z., Khorasani R., Levesque V.M., Gerbaudo V.H., Shyn P.B. Liver tumor F-18 FDG-PET before and immediately after microwave ablation enables imaging and quantification of tumor tissue contraction. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imag. 2021;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozaki K., Harada K., Terayama N., Kosaka N., Kimura H., Gabata T. FDG-PET/CT imaging findings of hepatic tumors and tumor-like lesions based on molecular background. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2020;38:697–718. doi: 10.1007/s11604-020-00961-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahrmeijer A.L., Hutteman M., van der Vorst J.R., van de Velde C.J.H., Frangioni J.V. Image-guided cancer surgery using near-infrared fluorescence. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013;10:507–518. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang P., Fan Y., Lu L., Liu L., Fan L., Zhao M., Xie Y., Xu C., Zhang F. NIR-II nanoprobes in-vivo assembly to improve image-guided surgery for metastatic ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2898. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widen J.C., Tholen M., Yim J.J., Antaris A., Casey K.M., Rogalla S., Klaassen A., Sorger J., Bogyo M. AND-gate contrast agents for enhanced fluorescence-guided surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021;5:264–277. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-00616-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Y., Shi Y., Wang H., Wang J., Ding D., Wang L., Yang Z. Environment-sensitive fluorescent supramolecular nanofibers for imaging applications. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:2193–2199. doi: 10.1021/ac4038653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stepp H., Stummer W. 5-ALA in the management of malignant glioma. Laser Surg. Med. 2018;50:399–419. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Z., Fang C., Li B., Zhang Z., Cao C., Cai M., Su S., Sun X., Shi X., Li C., Zhou T., Zhang Y., Chi C., He P., Xia X., Chen Y., Gambhir S.S., Cheng Z., Tian J. First-in-human liver-tumour surgery guided by multispectral fluorescence imaging in the visible and near-infrared-I/II windows. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:259–271. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller D.S., Ishizawa T., Cohen R., Chand M. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in colorectal surgery: overview, applications, and future directions. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;2:757–766. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(17)30216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzzo T.J., Jiang J., Keating J., DeJesus E., Judy R., Nie S., Low P., Lal P., Singhal S. Intraoperative molecular diagnostic imaging can identify renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 2016;195:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takemura N., Kokudo N. Do we need to shift from dye injection to fluorescence in respective liver surgery? Surg. Oncol. 2020;33:207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urano Y., Asanuma D., Hama Y., Koyama Y., Barrett T., Kamiya M., Nagano T., Watanabe T., Hasegawa A., Choyke P.L., Kobayashi H. Selective molecular imaging of viable cancer cells with pH-activatable fluorescence probes. Nat. Med. 2009;15:104–109. doi: 10.1038/nm.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golijanin J., Amin A., Moshnikova A., Brito J.M., Tran T.Y., Adochite R.-C., Andreev G.O., Crawford T., Engelman D.M., Andreev O.A., Reshetnyak Y.K., Golijanin D. Targeted imaging of urothelium carcinoma in human bladders by an ICG pHLIP peptide ex vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016;113:11829–11834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610472113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren C., Zhang J., Chen M., Yang Z. Self-assembling small molecules for the detection of important analytes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:7257–7266. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00161c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui H., Xu B. Supramolecular medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:6430–6432. doi: 10.1039/c7cs90102j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luby B.M., Charron D.M., MacLaughlin C.M., Zheng G. Activatable fluorescence: from small molecule to nanoparticle. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017;113:97–121. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lwin T.M., Hoffman R.M., Bouvet M. The development of fluorescence guided surgery for pancreatic cancer: from bench to clinic. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:651–662. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1477593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lv F., Qiu T., Liu L., Ying J., Wang S. Recent advances in conjugated polymer materials for disease diagnosis. Small. 2016;12:696–705. doi: 10.1002/smll.201501700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang K., Feng L., Liu Z. Stimuli responsive drug delivery systems based on nano-graphene for cancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;105:228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang P., Chou S.J., Li J., Hui W., Liu W., Sun N., Zhang R.Y., Zhu Y., Tsai M.L., Lai H.I., Smalley M., Zhang X., Chen J., Romero Z., Liu D., Ke Z., Zou C., Lee C.F., Jonas S.J., Ban Q., Weiss P.S., Kohn D.B., Chen K., Chiou S.H., Tseng H.R. Supramolecular nanosubstrate-mediated delivery system enables CRISPR-Cas9 knockin of hemoglobin beta gene for hemoglobinopathies. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.An H.-W., Li L.-L., Wang Y., Wang Z., Hou D., Lin Y.-X., Qiao S.-L., Wang M.-D., Yang C., Cong Y., Ma Y., Zhao X.-X., Cai Q., Chen W.-T., Lu C.-Q., Xu W., Wang H., Zhao Y. A tumour-selective cascade activatable self-detained system for drug delivery and cancer imaging. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4861. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12848-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang D., Qi G.-B., Zhao Y.-X., Qiao S.-L., Yang C., Wang H. In situ formation of nanofibers from purpurin18-peptide conjugates and the assembly induced retention effect in tumor sites. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:6125–6130. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.An H.-W., Hou D., Zheng R., Wang M.-D., Zeng X.-Z., Xiao W.-Y., Yan T.-D., Wang J.-Q., Zhao C.-H., Cheng L.-M., Zhang J.-M., Wang L., Wang Z.-Q., Wang H., Xu W. A near-infrared peptide probe with tumor-specific excretion-retarded effect for image-guided surgery of renal cell carcinoma. ACS Nano. 2020;14:927–936. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b08209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sofias A.M., Toner Y.C., Meerwaldt A.E., van Leent M.M.T., Soultanidis G., Elschot M., Gonai H., Grendstad K., Flobak Å., Neckmann U., Wolowczyk C., Fisher E.L., Reiner T., Davies C.L., Bjørkøy G., Teunissen A.J.P., Ochando J., Pérez-Medina C., Mulder W.J.M., Hak S. Tumor targeting by α(v)β(3)-Integrin-Specific lipid nanoparticles occurs via phagocyte hitchhiking. ACS Nano. 2020;14:7832–7846. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b08693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khatik R., Wang Z., Zhi D., Kiran S., Dwivedi P., Liang G., Qiu B., Yang Q. Integrin α(v)β(3) receptor overexpressing on tumor-targeted positive MRI-guided chemotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:163–176. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b16648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., Lin T., Zhang W., Jiang Y., Jin H., He H., Yang V.C., Chen Y., Huang Y. A prodrug-type, MMP-2-targeting nanoprobe for tumor detection and imaging. Theranostics. 2015;5:787–795. doi: 10.7150/thno.11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun L., Xie S., Ji X., Zhang J., Wang D., Lee S.J., Lee H., He H., Yang V.C. MMP-2-responsive fluorescent nanoprobes for enhanced selectivity of tumor cell uptake and imaging. Biomater Sci. 2018;6:2619–2626. doi: 10.1039/c8bm00593a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z., An H.-W., Hou D., Wang M., Zeng X., Zheng R., Wang L., Wang K., Wang H., Xu W. Addressable peptide self-assembly on the cancer cell membrane for sensitizing chemotherapy of renal cell carcinoma. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1807175. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.