Abstract

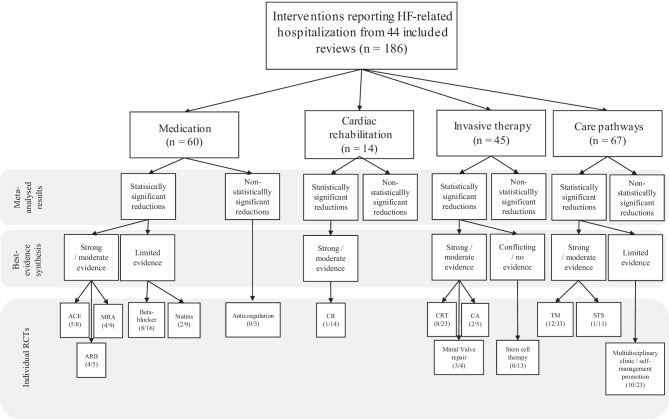

Heart failure (HF) is a major health concern, which accounts for 1–2% of all hospital admissions. Nevertheless, there remains a knowledge gap concerning which interventions contribute to effective prevention of HF (re)hospitalization. Therefore, this umbrella review aims to systematically review meta-analyses that examined the effectiveness of interventions in reducing HF-related (re)hospitalization in HFrEF patients. An electronic literature search was performed in PubMed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, Cochrane Reviews, CINAHL, and Medline to identify eligible studies published in the English language in the past 10 years. Primarily, to synthesize the meta-analyzed data, a best-evidence synthesis was used in which meta-analyses were classified based on level of validity. Secondarily, all unique RCTS were extracted from the meta-analyses and examined. A total of 44 meta-analyses were included which encompassed 186 unique RCTs. Strong or moderate evidence suggested that catheter ablation, cardiac resynchronization therapy, cardiac rehabilitation, telemonitoring, and RAAS inhibitors could reduce (re)hospitalization. Additionally, limited evidence suggested that multidisciplinary clinic or self-management promotion programs, beta-blockers, statins, and mitral valve therapy could reduce HF hospitalization. No, or conflicting evidence was found for the effects of cell therapy or anticoagulation. This umbrella review highlights different levels of evidence regarding the effectiveness of several interventions in reducing HF-related (re)hospitalization in HFrEF patients. It could guide future guideline development in optimizing care pathways for heart failure patients.

Keywords: Heart failure related hospitalizations, Interventions, Medication, Invasive therapy, Rehabilitations, Care pathways

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a major health concern, with mortality ranging from 5 to 40% [1], corresponding with a fivefold increased risk of death, compared to the general population [2]. It is even estimated that HF patients have a worse life expectancy than the majority of cancer patients, with a median survival of approximately 2 to 3 years [3, 4]. More than 400,000 patients in the USA are being diagnosed with HF, annually [5]. Moreover, prevalence rates are progressively rising and are expected to increase with 46% from 2012 to 2030 [6, 7].

In addition, heart failure is the diagnosis with the highest readmission rates among all diseases [8–11], as it accounts for 1 to 2% of all hospital admissions [12, 13]. In elderly people, it is the major cause of hospitalization [8]. Most patients are hospitalized at least once a year after diagnosis (i.e., 68 to 78% of patients) [8, 14, 15], and more than one-fourth is at risk of being readmitted within 30 days after initial diagnosis [8, 15–18]. Comparatively to prevalence rates, the total number of hospitalizations is also expected to rise, by 50% in the near future [19, 20].

Hospitalization places a great burden on patients [21]. Patients may experience various limitations in their activities of daily living [22–24], which highly impact their quality of life and level of satisfaction [21, 25]. Moreover, aside from a reduced quality of life, patients who are hospitalized have a significantly higher risk of death than non-hospitalized patients [26, 27]. Additionally, hospitalization due to HF places a great burden on the healthcare system, as it accounts for more than half of total healthcare costs [28, 29] corresponding with more than > 15 billion dollars a year for the American healthcare system [24, 30, 31]. HF is the most costly condition in western countries and since long time hospitalization for HF even exceeds the hospitalization costs for both cancer and myocardial infarction combined [32, 33]. Accordingly, hospitalization is judged as a highly important outcome measure in (inter)national literature and registries [34, 35].

Nevertheless, despite the rising prevalence rates, it seems that up to 40% of hospitalizations could be classified as preventable [36–40]. Therefore, the reduction of hospitalizations is the most promising factor as target to improve patients’ reported experiences or outcomes and to reduce the costs of HF management [25, 41, 42]. The combined measure of patient outcomes and costs are the main goal in value based healthcare, a well-known and promising strategy in healthcare in order to improve patient value [43–45].

Multiple previous studies examined the effect of various interventions to reduce (re)hospitalization in HF, mostly in patients with an left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40% (i.e., patients with HFrEF) [46], but contrasting findings are found within the literature regarding the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing hospital admissions [47, 48]. Moreover, there is some considerable heterogeneity in strategies and methods used in previous studies [49]. Some studies, for example, focused on remote monitoring to prevent readmissions, while others examined quality improvement of interventions or transitional care systems [36, 37, 50–52]. Therefore, there remains a gap in information concerning which interventions could effectively contribute to effective prevention of HF hospitalization or readmission [47, 48, 53, 54].

Hence, even though multiple interventions have been included in the guidelines for treatment of HF [46, 55], there is a compelling need of a comprehensive overview of which types of interventions prove effective specifically in reducing HF hospitalizations, especially in HFrEF patients. This umbrella review therefore aims to systematically review all published meta-analyses conducted in the past 10 years that examined the incremental effect of different interventions in addition to standard care, to reduce (re)hospitalization in HFrEF patients, in order to highlight different levels of evidence regarding their effectiveness.

Methods

The systematic review protocol of this review was registered, in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on July 6, 2020 (registration number: 247872).

Search strategy

An electronic literature search was performed in PubMed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, Cochrane Reviews, CINAHL, and Medline to identify eligible studies published in the English language from January 2010 up to the end of June 2020. Search terms were developed using MeSH terms. Key words were related to (1) interventions, (2) heart failure, (3) hospitalization, and (4) meta-analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy for each database

| Database | Search terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((telemedicine[Title/Abstract]) OR (telecare[Title/Abstract])) OR (teleconsultation[Title/Abstract])) OR (telecommunication[Title/Abstract])) OR (home monitoring[Title/Abstract])) OR (monitoring[Title/Abstract])) OR (tele*[Title/Abstract])) OR (tele med*[Title/Abstract])) OR (tele-med*[Title/Abstract])) OR (telehealth[Title/Abstract])) OR (tele-health[Title/Abstract])) OR (remote consult*[Title/Abstract])) OR (remote monitoring[Title/Abstract])) OR (remote patient monitoring[Title/Abstract])) OR (structured telephone support[Title/Abstract])) OR (structured scheduled telephone support[Title/Abstract])) OR (telephone support[Title/Abstract])) OR (telecardiol*[Title/Abstract])) OR (home care services[Title/Abstract])) OR (disease management[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient care team[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient discharge[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient education[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient aftercare[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient care planning[Title/Abstract])) OR (home care services[Title/Abstract])) OR (manage*[Title/Abstract])) OR (comprehensive discharge planning[Title/Abstract])) OR (discharge planning[Title/Abstract])) OR (hospital discharge[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient care planning[Title/Abstract])) OR (multidisciplinary care[Title/Abstract])) OR (care management[Title/Abstract])) OR (transition*[Title/Abstract])) OR (comprehensive health care[Title/Abstract])) OR (process of care[Title/Abstract])) OR (comprehensive care[Title/Abstract])) OR (multidisciplinary care[Title/Abstract])) OR (improve*[Title/Abstract])) OR (promot*[Title/Abstract])) OR (enhanc*[Title/Abstract])) OR (optimi*[Title/Abstract])) OR (quality of health care[Title/Abstract])) OR (improvement initiative[Title/Abstract])) OR (process* improvement[Title/Abstract])) OR (management quality circles[Title/Abstract])) OR (total quality management[Title/Abstract])) OR (guideline adherence[Title/Abstract])) OR (clinical competence[Title/Abstract])) OR (rehabilitation centers[Title/Abstract])) OR (exercise therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (sports[Title/Abstract])) OR (physicial exertion[Title/Abstract])) OR (exertion[Title/Abstract])) OR (exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (rehabilit*[Title/Abstract])) OR (lifestyle intervent*[Title/Abstract])) OR (life-style intervent*[Title/Abstract])) OR (psychotherapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (psychotherap*[Title/Abstract])) OR (psycholog*[Title/Abstract])) OR (psycholog* intervent*[Title/Abstract])) OR (self-care[Title/Abstract])) OR (relaxation therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (counseling[Title/Abstract])) OR (cognitive therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (behaviour therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (behavior therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (meditation[Title/Abstract])) OR (hypnotherap*[Title/Abstract])) OR (psycho-educat*[Title/Abstract])) OR (psychoeducat*[Title/Abstract])) OR (motiv* intervent*[Title/Abstract])) OR (health education[Title/Abstract])) OR (self-management[Title/Abstract])) OR (action plan*[Title/Abstract])) OR (medication[Title/Abstract])) OR (medication* treatment[Title/Abstract])) OR (pharmacotherapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (device* implantation[Title/Abstract])) OR (medication adherence[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient compliance[Title/Abstract])) OR (adherent[Title/Abstract])) OR (non-compliant[Title/Abstract])) OR (noncompliance[Title/Abstract])) OR (nonadherent[Title/Abstract])) OR (nonadherence[Title/Abstract])) OR (prescription drug[Title/Abstract])) OR (dosage forms[Title/Abstract])) OR (prescribed[Title/Abstract])) OR (pill*[Title/Abstract])) OR (invasisve HF monitoring[Title/Abstract])) OR (implanted monitoring devices[Title/Abstract])) OR (CRT[Title/Abstract])) OR (biventricular pacing[Title/Abstract])) OR (drug therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (intervention[Title/Abstract])) OR (interven*[Title/Abstract]))OR (immunization[Title/Abstract]))) OR (e-health[Title/Abstract])) OR (program[Title/Abstract])) OR (mobile health[Title/Abstract])) OR (mhealth[Title/Abstract])) OR (after-hours care[Title/Abstract])) OR (integrated delivery of health care[Title/Abstract])) OR (managed care programs[Title/Abstract])) OR (technological interventions[Title/Abstract])) OR (inventions[Title/Abstract])) OR (automation[Title/Abstract])) OR (program evaluation[Title/Abstract])) OR (standard of care[Title/Abstract])) AND (((((heart failure[Title/Abstract]) OR (cardiac failure[Title/Abstract])) OR (congestive*[Title/Abstract])) OR (left ventricular dysfunction[Title/Abstract])) OR (CHF[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((((((readmission*hospitalization*[Title/Abstract]) OR (rehospitalization*[Title/Abstract])) OR (admission*[Title/Abstract])) OR (re-admission*[Title/Abstract])) OR (readmission*[Title/Abstract])) OR (length of stay[Title/Abstract]))) AND (((((meta analysis[Title/Abstract]) OR (meta-analysis[Title/Abstract])) OR (meta analy*[Title/Abstract])) OR (metaanaly*[Title/Abstract])) OR (meta-analy*[Title/Abstract])) |

| Cochrane library |

#1(Telemedicine):ti,ab,kw OR (telecare):ti,ab,kw OR (teleconsultation):ti,ab,kw OR (telecommunication):ti,ab,kw OR (home monitoring):ti,ab,kw OR (monitoring):ti,ab,kw OR (tele*):ti,ab,kw OR (tele med):ti,ab,kw OR (tele-med*):ti,ab,kw OR (telehealth*):ti,ab,kw OR (tele-health*):ti,ab,kw OR (remote consult*):ti,ab,kw OR (remote monitoring):ti,ab,kw OR (remote patient monitoring):ti,ab,kw OR (structured telephone support):ti,ab,kw OR (structured scheduled telephone support):ti,ab,kw OR (telephone support):ti,ab,kw OR (telecardiol*):ti,ab,kw OR (home care services):ti,ab,kw OR (disease management):ti,ab,kw OR (patient care team):ti,ab,kw OR (patient discharge):ti,ab,kw OR (patient education):ti,ab,kw OR (patient aftercare):ti,ab,kw OR (patient care planning):ti,ab,kw OR (home care services):ti,ab,kw OR (manage*):ti,ab,kw OR (comprehensive discharge planning):ti,ab,kw OR (discharge planning):ti,ab,kw OR (hospital discharge):ti,ab,kw OR (patient care planning):ti,ab,kw OR (multidisciplinary care):ti,ab,kw OR (care management):ti,ab,kw OR (transition*):ti,ab,kw OR (comprehensive health care):ti,ab,kw OR (process of care):ti,ab,kw OR (comprehensive care):ti,ab,kw OR (multidisciplinary care):ti,ab,kw OR (improve*):ti,ab,kw OR (promot*):ti,ab,kw OR (enhanc*):ti,ab,kw OR (optimi*):ti,ab,kw OR (quality of health care):ti,ab,kw OR (improvement initiative):ti,ab,kw OR (process* improvement):ti,ab,kw OR (management quality circles):ti,ab,kw OR (total quality management):ti,ab,kw OR (guideline adherence):ti,ab,kw OR (clinical competence):ti,ab,kw OR (*rehabilitation centers):ti,ab,kw OR (exercise therapy):ti,ab,kw OR (*rehabilitation):ti,ab,kw OR (sports):ti,ab,kw OR (physical exertion):ti,ab,kw OR (exertion):ti,ab,kw OR (exercise):ti,ab,kw OR (rehabilit*):ti,ab,kw OR (lifestyle intervent*):ti,ab,kw OR (life-style intervent*):ti,ab,kw OR (psychotherapy):ti,ab,kw OR (psychotherap*):ti,ab,kw OR (psycholog*):ti,ab,kw OR (psycholog* intervent*):ti,ab,kw OR (self-care):ti,ab,kw OR (relaxation therapy):ti,ab,kw OR (counseling):ti,ab,kw OR (cognitive therapy):ti,ab,kw OR (behaviour therapy):ti,ab,kw OR (behavior therapy):ti,ab,kw OR (meditation):ti,ab,kw OR (hypnotherap*):ti,ab,kw OR (psycho-educat*):ti,ab,kw OR (psychoeducat*):ti,ab,kw OR (motiv* intervent*):ti,ab,kw OR (health education):ti,ab,kw OR ( self-management):ti,ab,kw OR (action plan*):ti,ab,kw OR (Medication):ti,ab,kw OR (medication* treatment):ti,ab,kw OR (pharmacotherapy):ti,ab,kw OR (device* implantation):ti,ab,kw OR (medication adherence):ti,ab,kw OR (patient compliance):ti,ab,kw OR (adherent):ti,ab,kw OR (non-compliant):ti,ab,kw OR (noncompliance):ti,ab,kw OR (nonadherent):ti,ab,kw OR (nonadherence):ti,ab,kw OR (prescription drugs):ti,ab,kw OR (dosage forms):ti,ab,kw OR (prescribed):ti,ab,kw OR (pill* ORinvasive HF monitoring):ti,ab,kw OR (implanted monitoring devices):ti,ab,kw OR (CRT):ti,ab,kw OR (biventricular pacing):ti,ab,kw OR (drug therapy):ti,ab,kw OR (intervention):ti,ab,kw OR (interven*):ti,ab,kw OR (e-health):ti,ab,kw OR (program):ti,ab,kw OR (mobile health):ti,ab,kw OR (mhealth):ti,ab,kw OR (after-hours care):ti,ab,kw OR (integrated delivery of health care):ti,ab,kw OR (managed care programs):ti,ab,kw OR (technological interventions):ti,ab,kw OR (inventions):ti,ab,kw OR (automation):ti,ab,kw OR (program evaluation):ti,ab,kw OR (standard of care):ti,ab,kw OR (OR influenza):ti,ab,kw #2(meta analysis):ti,ab,kw OR (meta-analysis):ti,ab,kw OR (meta analy*):ti,ab,kw OR (metaanaly*):ti,ab,kw OR (meta-analy*):ti,ab,kw #3(hospitalization*):ti,ab,kw OR (rehospitalization*):ti,ab,kw OR (admission*):ti,ab,kw OR (re-admission*):ti,ab,kw OR (readmission*):ti,ab,kw OR (length of stay):ti,ab,kw #4(*Heart failure):ti,ab,kw OR (cardiac failure):ti,ab,kw OR (congestive*):ti,ab,kw OR (left ventricular dysfunction):ti,ab,kw OR (CHF):ti,ab,kw #5#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

| Web of Science |

#1: TS = (Telemedicine OR telecare OR teleconsultation OR telecommunication OR home monitoring OR monitoring OR tele* OR tele med OR telemed* OR telehealth* OR telehealth* OR remote consult* OR remote monitoring OR remote patient monitoring OR structured telephone support OR structured scheduled telephone support OR telephone support OR telecardiol* OR home care services OR disease management OR patient care team OR patient discharge OR patient education OR patient aftercare OR patient care planning OR home care services OR manage* OR comprehensive discharge planning OR discharge planning OR hospital discharge OR patient care planning OR multidisciplinary care OR care management OR transition* OR comprehensive health care OR process of care OR comprehensive care OR multidisciplinary care OR improve* OR promot* OR enhanc* OR optimi* OR quality of health care OR improvement initiative OR process* improvement OR management quality circles OR total quality management OR guideline adherence OR clinical competence OR *rehabilitation centers OR exercise therapy OR *rehabilitation OR sports OR physical exertion OR exertion OR exercise OR rehabilit* OR lifestyle intervent* OR life-style intervent* OR psychotherapy OR psychotherap* OR psycholog* OR psycholog* intervent* OR self-care OR relaxation therapy OR counseling OR cognitive therapy OR behaviour therapy OR behavior therapy OR meditation OR hypnotherap* OR psycho-educat* OR psychoeducat* OR motiv* intervent* OR health education OR self-management OR action plan* OR Medication OR medication* treatment OR pharmacotherapy OR device* implantation OR medication adherence OR patient compliance OR adherent OR non-compliant OR noncompliance OR nonadherent OR nonadherence OR prescription drugs OR dosage forms OR prescribed OR pill* ORinvasive HF monitoring OR implanted monitoring devices OR CRT OR biventricular pacing OR drug therapy OR intervention OR interven* OR e-health OR program OR mobile health OR mhealth OR after-hours care OR integrated delivery of health care OR managed care programs OR technological interventions OR inventions OR automation OR program evaluation OR standard of care) #2: TS = (meta analysis OR meta-analysis OR meta analy* OR metaanaly* OR meta-analy*) #3: TS = (hospitalization* OR rehospitalization* OR admission* OR re-admission* OR readmission* OR length of stay) #4: TS = (*Heart failure OR cardiac failure OR congestive* OR left ventricular dysfunction OR CHF) #5: #4 AND #3 AND #2 AND #1 |

| Psycinfo | TX ( Telemedicine OR telecare OR teleconsultation OR telecommunication OR home monitoring OR monitoring OR tele* OR tele med OR tele-med* OR telehealth* OR tele-health* OR remote consult* OR remote monitoring OR remote patient monitoring OR structured telephone support OR structured scheduled telephone support OR telephone support OR telecardiol* OR home care services OR disease management OR patient care team OR patient discharge OR patient education OR patient aftercare OR patient care planning OR home care services OR manage* OR comprehensive discharge planning OR discharge planning OR hospital discharge OR patient care planning OR multidisciplinary care OR care management OR transition* OR comprehensive health care OR process of care OR comprehensive care OR multidisciplinary care OR improve* OR promot* OR enhanc* OR optimi* OR quality of health care OR improvement initiative OR process* improvement OR management quality circles OR total quality management OR guideline adherence OR clinical competence OR *rehabilitation centers OR exercise therapy OR *rehabilitation OR sports OR physical exertion OR exertion OR exercise OR rehabilit* OR lifestyle intervent* OR life-style intervent* OR psychotherapy OR psychotherap* OR psycholog* OR psycholog* intervent* OR self-care OR relaxation therapy OR counseling OR cognitive therapy OR behaviour therapy OR behavior therapy OR meditation OR hypnotherap* OR psycho-educat* OR psychoeducat* OR motiv* intervent* OR health education OR self-management OR action plan* OR Medication OR medication* treatment OR pharmacotherapy OR device* implantation OR medication adherence OR patient compliance OR adherent OR non-compliant OR noncompliance OR nonadherent OR nonadherence OR prescription drugs OR dosage forms OR prescribed OR pill* ORinvasive HF monitoring OR implanted monitoring devices OR CRT OR biventricular pacing OR drug therapy OR intervention OR interven* OR e-health OR program OR mobile health OR mhealth OR after-hours care OR integrated delivery of health care OR managed care programs OR technological interventions OR inventions OR automation OR program evaluation OR standard of care) AND TX ( meta analysis OR meta-analysis OR meta analy* OR metaanaly* OR meta-analy*) AND TX ( hospitalization* OR rehospitalization* OR admission* OR re-admission* OR readmission* OR length of stay) AND TX ( *Heart failure OR cardiac failure |

| Medline | AB ( Telemedicine OR telecare OR teleconsultation OR telecommunication OR home monitoring OR monitoring OR tele* OR tele med OR tele-med* OR telehealth* OR tele-health* OR remote consult* OR remote monitoring OR remote patient monitoring OR structured telephone support OR structured scheduled telephone support OR telephone support OR telecardiol* OR home care services OR disease management OR patient care team OR patient discharge OR patient education OR patient aftercare OR patient care planning OR home care services OR manage* OR comprehensive discharge planning OR discharge planning OR hospital discharge OR patient care planning OR multidisciplinary care OR care management OR transition* OR comprehensive health care OR process of care OR comprehensive care OR multidisciplinary care OR improve* OR promot* OR enhanc* OR optimi* OR quality of health care OR improvement initiative OR process* improvement OR management quality circles OR total quality management OR guideline adherence OR clinical competence OR *rehabilitation centers OR exercise therapy OR *rehabilitation OR sports OR physical exertion OR exertion OR exercise OR rehabilit* OR lifestyle intervent* OR life-style intervent* OR psychotherapy OR psychotherap* OR psycholog* OR psycholog* intervent* OR self-care OR relaxation therapy OR counseling OR cognitive therapy OR behaviour therapy OR behavior therapy OR meditation OR hypnotherap* OR psycho-educat* OR psychoeducat* OR motiv* intervent* OR health education OR self-management OR action plan* OR Medication OR medication* treatment OR pharmacotherapy OR device* implantation OR medication adherence OR patient compliance OR adherent OR non-compliant OR noncompliance OR nonadherent OR nonadherence OR prescription drugs OR dosage forms OR prescribed OR pill* ORinvasive HF monitoring OR implanted monitoring devices OR CRT OR biventricular pacing OR drug therapy OR intervention OR interven* OR e-health OR program OR mobile health OR mhealth OR after-hours care OR integrated delivery of health care OR managed care programs OR technological interventions OR inventions OR automation OR program evaluation OR standard of care OR) AND AB ( meta analysis OR meta-analysis OR meta analy* OR metaanaly* OR meta-analy) AND AB ( hospitalization* OR rehospitalization* OR admission* OR re-admission* OR readmission* OR length of stay) AND AB ( Heart failure OR cardiac failure OR congestive* OR left ventricular dysfunction OR CHF) |

| CINAHL | AB ( Telemedicine OR telecare OR teleconsultation OR telecommunication OR home monitoring OR monitoring OR tele* OR tele med OR tele-med* OR telehealth* OR tele-health* OR remote consult* OR remote monitoring OR remote patient monitoring OR structured telephone support OR structured scheduled telephone support OR telephone support OR telecardiol* OR home care services OR disease management OR patient care team OR patient discharge OR patient education OR patient aftercare OR patient care planning OR home care services OR manage* OR comprehensive discharge planning OR discharge planning OR hospital discharge OR patient care planning OR multidisciplinary care OR care management OR transition* OR comprehensive health care OR process of care OR comprehensive care OR multidisciplinary care OR improve* OR promot* OR enhanc* OR optimi* OR quality of health care OR improvement initiative OR process* improvement OR management quality circles OR total quality management OR guideline adherence OR clinical competence OR *rehabilitation centers OR exercise therapy OR *rehabilitation OR sports OR physical exertion OR exertion OR exercise OR rehabilit* OR lifestyle intervent* OR life-style intervent* OR psychotherapy OR psychotherap* OR psycholog* OR psycholog* intervent* OR self-care OR relaxation therapy OR counseling OR cognitive therapy OR behaviour therapy OR behavior therapy OR meditation OR hypnotherap* OR psycho-educat* OR psychoeducat* OR motiv* intervent* OR health education OR self-management OR action plan* OR Medication OR medication* treatment OR pharmacotherapy OR device* implantation OR medication adherence OR patient compliance OR adherent OR non-compliant OR noncompliance OR nonadherent OR nonadherence OR prescription drugs OR dosage forms OR prescribed OR pill* ORinvasive HF monitoring OR implanted monitoring devices OR CRT OR biventricular pacing OR drug therapy OR intervention OR interven* OR e-health OR program OR mobile health OR mhealth OR after-hours care OR integrated delivery of health care OR managed care programs OR technological interventions OR inventions OR automation OR program evaluation OR standard of care) AND AB ( meta analysis OR meta-analysis OR meta analy* OR metaanaly* OR meta-analy*) AND AB ( hospitalization* OR rehospitalization* OR admission* OR re-admission* OR readmission* OR length of stay) AND AB ( Heart failure OR cardiac failure OR congestive* OR left ventricular dysfunction OR CHF) |

Ample differences existed in the classification of categories of interventions depicted in the existing literature. For example, previous reviews classified interventions in either educational interventions, pharmacological interventions, telemonitoring (TM), structured telephone support (STS), nurse home visits, nurse care management, and disease management clinics [41]; or discharge planning protocols, comprehensive geriatric assessments, discharge support arrangements, and educational interventions [56]; or case management interventions, clinical interventions, and multidisciplinary interventions [53]; or predischarge interventions, postdischarge interventions, and interventions bridging the transition [57]. A list of 4 categories of interventions was derived following a scoping review that combine the most common interventions aimed at reducing hospital (re)admissions, cardiac rehabilitation, care pathways, medication, and invasive treatment. Both general terms linked to the concept of interventions (e.g., programs, inventions, therapy) and terms for specific examples of (categories of) interventions were included in the search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

Search results of all databases were combined, and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened against the following inclusion criteria: (1) a meta-analysis was conducted, on (2) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), (3) that examined the effectiveness of (3.a) cardiac rehabilitation, or (3.b) care pathways, or (3.c) medication, or (3.d) invasive therapy, (4) in patients with an established diagnosis of chronic heart failure, (5) with an LVEF < 40, (6) with a primary or secondary objective to evaluate the effect on reduction of (7) HF-related hospitalization or readmissions, (8) as compared to usual care, (9) conducted in the past 10 years, (10) followed patients for at least three months, and (11) were reported in English. Meta-analyses that included both RCTs and observational or cohort studies were not excluded. Yet only the included RCTs (and corresponding meta-analyzed effect sized) were extracted and used for our analyses. Only meta-analyses that reported at least one meta-analyzed effect estimate for HF-related admissions were included. In order to assure objective assessment, the title and abstract screening were independently conducted by two researchers (FH, TG). In case of disagreement between reviewers, points of disagreement were discussed in order to reach consensus. For full-text screening, inter-rate reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa.

Studies were excluded when the patient population was not primarily diagnosed with heart failure (e.g., patients with diabetes and comorbid heart failure). Additionally, if studies examined HF patients in combination with other patient groups yet did not report data on the individual patient groups, the study was excluded, as we would otherwise be unable to make a distinction between the differences in patient groups. Furthermore, studies that only reported data on a combined endpoint (e.g., mortality in conjunction with HF-hospitalization) and meta-analyses that examined risk stratification, prognostic factors, or lifestyle advice in patients were excluded. Moreover, meta-analyses were also excluded when examining a specific subgroup of HF patients (e.g., patients with and LVAD) or when examining a broader category of patients that could possibly include HF patients (e.g., “older patients” in general).

Quality assessment

The “A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews 2” (AMSTAR 2) was used to assess the methodological quality of included meta-analyses [58]. AMSTAR 2 consists of 16 items, of which 10 items were retained from the original AMSTAR tool. Response options for the items were “yes,” “partial yes,” and “no,” with “yes” responses denoting a positive result. The overall score of this tool was converted to high quality, moderate quality, low quality, and critically low quality. High quality was achieved when studies possessed no or one non-critical weakness; moderate quality was achieved when studies had more than one non-critical weakness; low quality was achieved when studies had one critical flaw, with or without a non-critical weakness; and critically low quality was achieved when studies exhibited more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses. Critical domains are depicted in Table 2 [58]. In order to assure objective assessment, the quality assessment was independently conducted by two researchers (GS, TG). In case of disagreement between reviewers, points of disagreement were discussed in order to reach consensus (RT).

Table 2.

Critical domains of the AMSTAR 2

| Registered protocol before commencement of the review |

| Risk of bias from individual studies being included in the review |

| Appropriateness of meta-analytical methods |

| Consideration of risk of bias when interpreting the results of the review |

| Assessment of presence and likely impact of publication bias |

Data extraction

A standardized extraction form was used to extract data from the included studies. Sociodemographic data (e.g., age, sex), number of participants, left ventricular ejection fraction, type of intervention and control, follow-up period, effect size, and conclusion were extracted from either the individual RCT or the meta-analysis in which the RCT was included. Only the most recent meta-analysis was included when multiple articles were written by the same authors on the same dataset. Comparisons were made between the different categories of interventions in terms of effectiveness in reducing HF-related (re)hospitalization. Interventions were classified as having a significant effect on HF-related (re)hospitalization (as compared to usual care) based on their own reported RR statistics, findings, and conclusions.

Data synthesis

Interventions were first classified into the four predefined categories (i.e., cardiac rehabilitation, care pathways, medication, and invasive therapy) and subsequently divided into more detailed classes of interventions (e.g., TM and STS) to examine the exact effect of all unique interventions.

Primary analysis: meta-analyses

To synthesize the data, a best-evidence synthesis was used as primary analysis, in which meta-analyses were classified based on level of internal and external validity [59]. The levels of evidence regarding the significance or non-significance of a relationship between the intervention and HF-related hospitalization among studies were ranked according to the following statements: (1) strong evidence: consistent findings (> 75% of the studies reported consistent findings) in multiple high quality studies; (2) moderate evidence: consistent findings (> 75% of the studies reported consistent findings) in one high-quality study and two or more moderate quality studies or in three or more weak quality studies; (3) limited evidence: generally consistent findings (> 75% of the studies reported consistent findings) in a high quality study or in two or fewer moderate quality studies; (4) no evidence: no studies could be found; (5) conflicting evidence: conflicting findings.

Secondary analysis: extracted RCTs

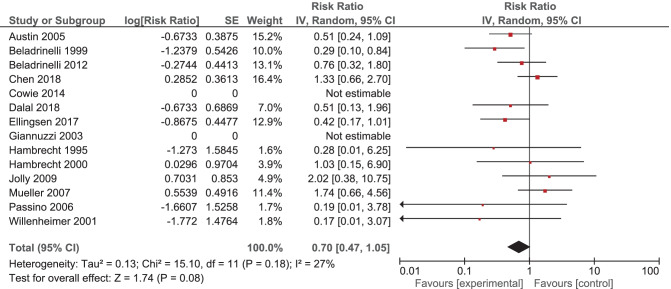

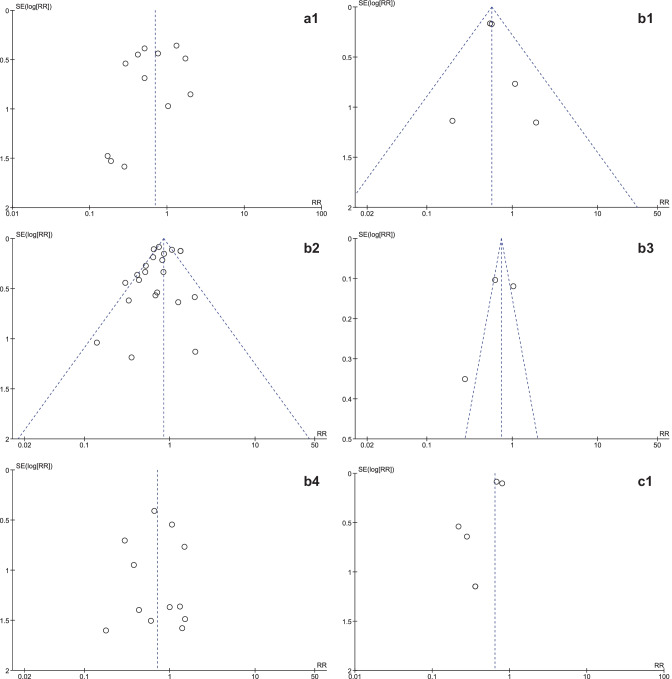

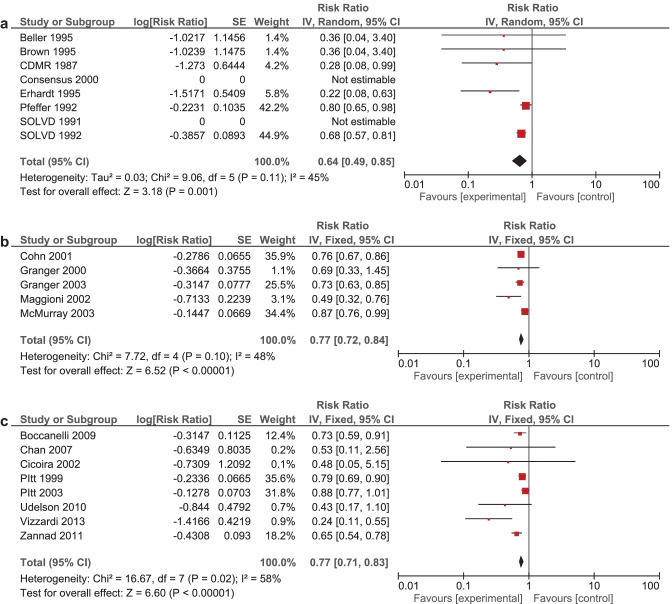

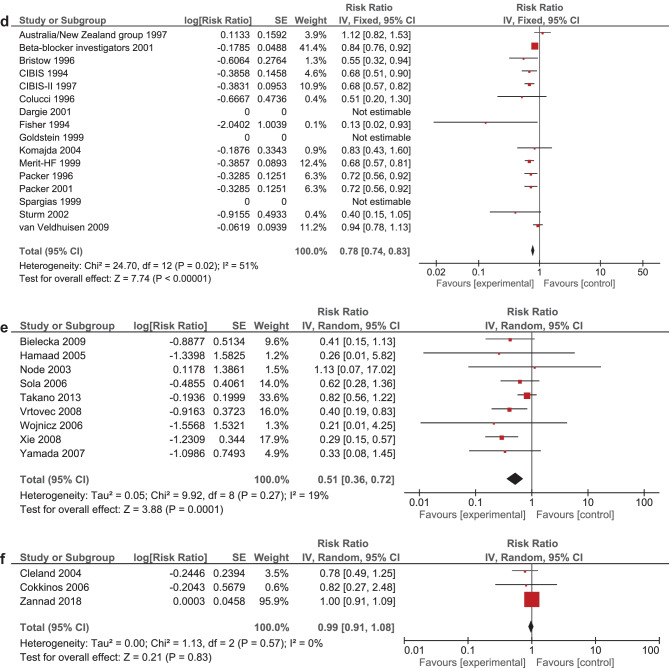

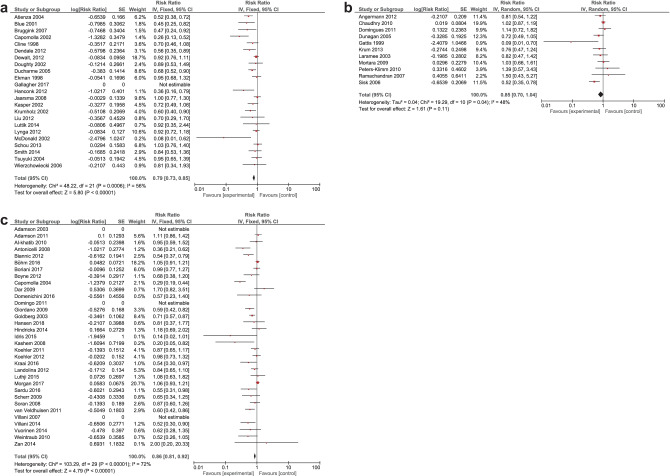

It was expected that multiple meta-analyses would report identical RCTs, as it was previously found that the amount of redundancy and duplication among reviews is substantial [60, 61]. Therefore, the corrected covered area (CCA) was calculated, which is a measure of duplicates in meta-analyses divided by the frequency of duplicates, reduced by the number of original publications [62]. A CCA of 0–5% is considered as slight overlap, while 6–10%, 11–15%, > 15% are respectively regarded as moderate, high, and very high overlap. In order to prevent bias as a result of duplicated data, a secondary analysis was conducted to control for the effects of overlap. All unique RCTs were extracted from the meta-analyses. Individual risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs for each intervention were calculated using Review Manager V.5.4. or extracted from the meta-analyses. The I2-statistic was used to present the heterogeneity of intervention effect. When the I2-statistic was statistically significant, a random-effects model was used in analyses. The RR-statistics found in our own meta-analyses were compared to the reported effects in the published meta-analyses.

Results

Search results

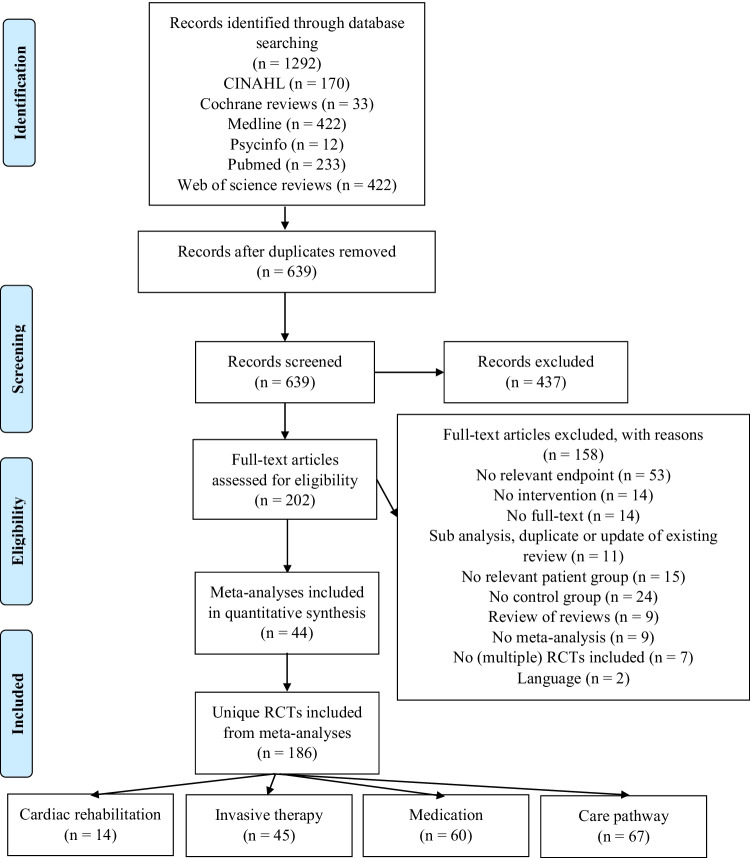

After removal of duplicate meta-analyses, 639 titles and abstracts were screened (see Fig. 1). A total of 202 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 44 were included in our analyses. Cohen’s kappa for full-text screening was 0.76, indicating substantial agreement [63]. Median year of publication of all included meta-analyses was 2018. The 44 included meta-analyses encompassed 348 RCTs of which 186 were unique RCTs regarding interventions to prevent HF hospitalization (Table 3). Of these 186 unique RCTs, 44 were classified as invasive therapy, 14 as cardiac rehabilitation, 60 as medication, and 67 as care pathways (Table 4). The CCA for cardiac revalidation was , the CCA for invasive therapy was , the CCA for medication was , and the CCA for care pathways was . This indicates a moderate to very high overlap in included RCTs [62].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion. RCT: randomized controlled trial

Table 3.

Overlap between different meta-analyses in included RCTs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al. [87] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Abraham et al. [88] | 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adamson et al. [89] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adamson et al. [90] | 2011 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Al-khatib et al. [91] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Angermann et al. [92] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Antonicelli et al. [93] | 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Asgar et al. [94] | 2017 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Assmus et al. [95] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Assmus et al. [96] | 2013 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Atienza et al. [97] | 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Austin et al. [98] | 2005 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Australia/New Zealand Heart Failure Group [99] | 1997 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bartunek et al. [100] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Belardinelli et al. [101] | 1999 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Belardinelli et al. [102] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Beller et al. [103] | 1995 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bentkover et al. [104] | 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beta-Blocker evaluation of survival trial [105] | 2001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Biannic et al. [106] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bielecka-Dabrowa et al. [107] | 2009 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Blue et al. [108] | 2001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boccanelli et al. [109] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Böhm et al. [110] | 2016 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bolli et al. [111] | 2011 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Boriani et al. [112] | 2017 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Boyne et al. [113] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bristow et al. [114] | 1996 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brown et al. [115] | 1995 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lok et al. [116] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capomolla et al. [117] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cazeau et al. [118] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| CDMR [119] | 1988 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chan et al. [120] | 2007 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chaudhry et al. [69] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen et al. [121] | 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chung [122] | 2021 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| CIBIS [123] | 1994 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| CIBIS-II [124] | 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cicoira et al. [125] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cleland et al. [126] | 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cline et al. [127] | 1998 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cohn and Tognoni [128] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cokkinos et al. [129] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colucci et al. [130] | 1996 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consensus et al. [241] | 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cowie et al. [131] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dalal et al. [132] | 2019 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dar et al. [133] | 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dargie [134] | 2001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daubert et al. [135] | 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dendale et al. [136] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dewalt et al. [137] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Di Biase et al. [138] | 2016 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| DIG [139] | 1997 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domenichini et al. [140] | 2016 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Domingo et al. [141] | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domingues et al. [142] | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doughty et al. [143] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ducharme et al. [144] | 2005 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dunagan et al. [145] | 2005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ekman et al. [146] | 1998 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ellingsen et al. [147] | 2017 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Erhardt et al. [148] | 1995 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fisher et al. [149] | 1994 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fox et al. [150] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fragasso et al. [151] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gallagher et al. [152] | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gasparini et al. [153] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gattis et al. [154] | 1999 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Giannini et al. [155] | 2016 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Giannuzzi et al. [156] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Giordano et al. [157] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldberg et al. [158] | 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldstein et al. [159] | 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Granger et al. [160] | 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Granger et al. [161] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamaad et al. [162] | 2005 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hambrecht et al. [163] | 1995 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hambrecht et al. [164] | 2000 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamshere et al. [165] | 2015 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanconk et al. [166] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hansen et al. [167] | 2018 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Heldman et al. [168] | 2014 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Heldman et al. [168] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Higgins et al. [169] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hindricks et al. [170] | 2014 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Idris et al. [171] | 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jaarsma et al. [47] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jolly et al. [172] | 2009 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jones and Wong [173] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kashem et al. [174] | 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kasper et al. [175] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Koehler et al. [176] | 2011 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Komajda [177] | 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kraai et al. [178] | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Krum et al. [179] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Krumholz et al. [180] | 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Landolina et al. [181] | 2012 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Laramee et al. [182] | 2003 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Linde et al. [183] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Leclercq et al. [184] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Linde et al. [185] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Liu et al. [186] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lüthje et al. [187] | 2015 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Luttik et al. [188] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyngå et al. [68] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| MacDonald et al. [189] | 2011 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Maggioni et al. [190] | 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Margulies et al. [191] | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marrouche et al. [192] | 2018 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Martinelli et al. [193] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mathiasen et al. [194] | 2015 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Menasché [195] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mcdonald et al. [196] | 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| McMurray et al. [197] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| MERIT-HF [198] | 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Morgan et al. [199] | 2017 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mortara et al. [200] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Moss et al. [201] | 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moss et al. [202] | 2009 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mozid et al. [203] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mueller et al. [204] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Node et al. [205] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Obadia et al. [206] | 2018 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [207] | 1993 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [208] | 1996 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [209] | 1996 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [210] | 2001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Passino et al. [211] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Patel et al. [212] | 2015 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pätilä et al. [213] | 2014 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Perin et al. [214] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Peters-klimm et al. [215] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pfeffer et al. [216] | 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Piepoli et al. [217] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pinter et al. [218] | 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pitt et al. [219] | 1999 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pitt et al. [220] | 2003 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pokushalov et al. [221] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pokushalov et al. [222] | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prabhu et al. [223] | 2017 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ramachandran et al. [224] | 2007 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosano et al. [225] | 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruschitzka et al. [226] | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sardu et al. [227] | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scherr et al. [228] | 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Schou et al. [229] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sisk et al. [230] | 2006 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Smith et al. [231] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sola et al. [232] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yusuf et al. [233] | 1991 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yusuf et al. [234] | 1992 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Spargias et al. [235] | 1999 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Stone et al. [236] | 2018 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sturm et al. [237] | 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Swedberg et al. [238] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Takano et al. [239] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tang et al. [240] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Consensus et al. [241] | 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thibault et al. [242] | 2011 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Thibault et al. [243] | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tsuyuki et al. [244] | 2004 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuunanen et al. [245] | 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Udelson et al. [246] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Uretsky et al. [247] | 1993 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| van Veldhuisen et al. [248] | 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| van Veldhuisen et al. [249] | 2011 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Villani et al. [250] | 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Villani et al. [251] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vitale et al. [252] | 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vizzardi et al. [253] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vrtovec et al. [254] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vuorinen et al. [255] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Weintraub et al. [256] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wierzchowiecki et al. [257] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Willenheimer et al. [258] | 2001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wojnicz et al. [259] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Xie et al. [260] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yamada et al. [261] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Young et al. [262] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Zan [263] | 2020 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Zannad et al. [264] | 2011 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Zannad et al. [265] | 2018 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al. [87] | 2002 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Abraham et al. [88] | 2004 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adamson et al. [89] | 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adamson et al. [90] | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Al-khatib et al. [91] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Angermann et al. [92] | 2012 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Antonicelli et al. [93] | 2008 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Asgar et al. [94] | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assmus et al. [95] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assmus et al. [96] | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atienza et al. [97] | 2004 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Austin et al. [98] | 2005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australia/New Zealand Heart Failure Group [99] | 1997 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bartunek et al. [100] | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belardinelli et al. [101] | 1999 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Belardinelli et al. [102] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beller et al. [103] | 1995 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bentkover et al. [104] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Beta-Blocker evaluation of survival trial [105] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Biannic et al. [106] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bielecka-Dabrowa et al. [107] | 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blue et al. [108] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Boccanelli et al. [109] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Böhm et al. [110] | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bolli et al. [111] | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boriani et al. [112] | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boyne et al. [113] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bristow et al. [114] | 1996 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Brown et al. [115] | 1995 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lok et al. [116] | 2007 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capomolla et al. [117] | 2002 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cazeau et al. [118] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| CDMR [119] | 1988 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chan et al. [120] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chaudhry et al. [69] | 2010 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen et al. [121] | 2018 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chung [122] | 2021 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| CIBIS [123] | 1994 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CIBIS-II [124] | 1999 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cicoira et al. [125] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cleland et al. [126] | 2004 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cline et al. [127] | 1998 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cohn and Tognoni [128] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cokkinos et al. [129] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Colucci et al. [130] | 1996 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Consensus et al. [241] | 2000 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cowie et al. [131] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dalal et al. [132] | 2019 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dar et al. [133] | 2009 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dargie [134] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Daubert et al. [135] | 2009 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dendale et al. [136] | 2012 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Dewalt et al. [137] | 2012 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Di Biase et al. [138] | 2016 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| DIG [139] | 1997 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Domenichini et al. [140] | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domingo et al. [141] | 2011 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Domingues et al. [142] | 2011 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Doughty et al. [143] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ducharme et al. [144] | 2005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dunagan et al. [145] | 2005 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ekman et al. [146] | 1998 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ellingsen et al. [147] | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Erhardt et al. [148] | 1995 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fisher et al. [149] | 1994 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fox et al. [150] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fragasso et al. [151] | 2006 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gallagher et al. [152] | 2017 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gasparini et al. [153] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gattis et al. [154] | 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Giannini et al. [155] | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Giannuzzi et al. [156] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Giordano et al. [157] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldberg et al. [158] | 2003 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldstein et al. [159] | 1999 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Granger et al. [160] | 2000 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Granger et al. [161] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamaad et al. [162] | 2005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hambrecht et al. [163] | 1995 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hambrecht et al. [164] | 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamshere et al. [165] | 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanconk et al. [166] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hansen et al. [167] | 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heldman et al. [168] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heldman et al. [168] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higgins et al. [169] | 2003 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hindricks et al. [170] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Idris et al. [171] | 2015 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jaarsma et al. [47] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jolly et al. [172] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Jones and Wong [173] | 2013 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kashem et al. [174] | 2008 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kasper et al. [175] | 2002 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Koehler et al. [176] | 2011 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Komajda et al. [177] | 2004 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kraai et al. [178] | 2016 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Krum et al. [179] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Krumholz et al. [180] | 2002 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Landolina et al. [181] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Laramee et al. [182] | 2003 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Linde et al. [183] | 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leclercq et al. [184] | 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linde et al. [185] | 2008 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Liu et al. [186] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lüthje et al. [187] | 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Luttik et al. [188] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyngå et al. [68] | 2012 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| MacDonald et al. [189] | 2011 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Maggioni et al. [190] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Margulies et al. [191] | 2016 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Marrouche et al. [192] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Martinelli et al. [193] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mathiasen et al. [194] | 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Menasché [195] | 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mcdonald et al. [196] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| McMurray et al. [197] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| MERIT-HF [198] | 1999 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Morgan et al. [199] | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mortara et al. [200] | 2009 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Moss et al. [201] | 2002 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Moss et al. [202] | 2009 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mozid et al. [203] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mueller et al. [204] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Node et al. [205] | 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Obadia et al. [206] | 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [207] | 1993 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [208] | 1996 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [209] | 1996 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Packer et al. [210] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Passino et al. [211] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Patel et al. [212] | 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pätilä et al. [213] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perin et al. [214] | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peters-klimm et al. [215] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pfeffer et al. [216] | 1992 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Piepoli et al. [217] | 2008 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pinter et al. [218] | 2009 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pitt et al. [219] | 1999 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pitt et al. [220] | 2003 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pokushalov et al. [221] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pokushalov et al. [222] | 2011 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prabhu et al. [223] | 2017 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ramachandran et al. [224] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosano et al. [225] | 2003 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruschitzka et al. [226] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sardu et al. [227] | 2016 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Scherr et al. [228] | 2009 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Schou et al. [229] | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sisk et al. [230] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Smith et al. [231] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sola et al. [232] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yusuf et al. [233] | 1991 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Yusuf et al. [234] | 1992 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spargias et al. [235] | 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stone et al. [236] | 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sturm et al. [237] | 2000 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Swedberg et al. [238] | 2010 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Takano et al. [239] | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tang et al. [240] | 2010 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Consensus et al. [241] | 2000 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Thibault et al. [242] | 2011 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Thibault et al. [243] | 2013 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tsuyuki et al. [244] | 2004 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuunanen et al. [245] | 2008 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Udelson et al. [246] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uretsky et al. [247] | 1993 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| van Veldhuisen et al. [248] | 2009 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| van Veldhuisen et al. [249] | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Villani et al. [250] | 2007 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Villani et al. [251] | 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vitale et al. [252] | 2004 | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vizzardi et al. [253] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vrtovec et al. [254] | 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vuorinen et al. [255] | 2014 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Weintraub et al. [256] | 2010 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wierzchowiecki et al. [257] | 2006 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Willenheimer et al. [258] | 2001 | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wojnicz et al. [259] | 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xie et al. [260] | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yamada et al. [261] | 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young et al. [262] | 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zan [263] | 2020 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zannad et al. [264] | 2011 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zannad et al. [265] | 2018 | x |

1, Adamson et al. [266]; 2, Agasthi et al. [267]; 3, Al-Majed et al. [268]; 4, Alotaibi et al. [269]; 5, AlTurki et al. [270]; 6, Benito-González et al. [271]; 7, Bertaina et al. [272]; 8, Bjarnason-Wehrens et al. [273]; 9, Bonsu et al. [274]; 10, Carbo et al. [275]; 11, de Vecchis et al. [276]; 12, Driscoll et al. [277]; 13, Emdin et al. [278]; 14, Fisher et al. [279]; 15, Fisher et al. [280]; 16, Gandhi et al. [281]; 17, Halawa et al. [282]; 18, Hartmann et al. [283]; 19, Hu et al. [284]; 20, Inglis et al. [285]; 21, Inglis et al. [286]; 22, Japp et al. [287]; 23, Jonkman et al. [288]; 24, Kang et al. [289]; 25, Klersy et al. [290]; 26, Komajda et al. [291]; 27, Le et al. [292]; 28, Ma et al. [293]; 29, Malik et al. [294]; 30, Moschonas et al. [295]; 31, Pandor et al. [296]; 32, Shah et al. [297]; 33, Sulaica et al. [298]; 34, Taylor et al. [299]; 35, Thomas et al. [300]; 36, Thomsen et al. [301]; 37, Tse et al. [302]; 38, Tu et al. [303]; 39, Turagam et al. [304]; 40, Uminski et al. [305]; 41, Xiang et al. [306]; 42, Zhang et al. [307]; 43, Zhang et al. [308]; 44, Zhou and Chen [309]

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of RCTs

| Included RCTs | N (intervention) | N (control) | Total | Mean age | % Male | Mean LVEF | Intervention | Control | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beller et al. [103] | 130 | 63 | 193 | 61 | 76 | 28 | Initial oral dose of 5 mg of lisinopril. The dose of diuretic therapy was adjusted based on the clinical condition of the patient, particularly to control edema | Matching placebo | 3 months |

| Brown et al. [115] | 116 | 125 | 241 | 62 | 82 | 25 | The 24-week double-blind treatment period beginning with 10 mg of fosinopril. In the ensuing 3 weeks, patients were titrated to 20 mg of study medication (level TI), as tolerated | Matching placebo | N/R |

| CDMR [119] | 200 | 100 | 300 | 57 | 83 | 25 | Captopril (25 to 50 mg, three times a day) | Placebo | 6 months |

| Consensus et al. [241] | 127 | 126 | 263 | 71 | 56 | < 40 | Enalapril (2.5 to 40 mg/day) | Placebo | 12 months |

| Erhardt et al. [148] | 155 | 153 | 308 | 64 | 76 | 27 | Fosinopril 10 mg | Matching placebo | 12 weeks |

| Pfeffer et al. [216] | 1115 | 1116 | 2231 | 60 | 83 | 31 | Captopril | Placebo | 36 months |

| Yusuf et al. [233] | 1285 | 1284 | 2569 | 61 | 81 | 25 | Enalapril | Placebo | 41 months |

| Yusuf et al. [234] | 2111 | 2117 | 4228 | 59 | 89 | 28 | Enalapril | Placebo | 42 months |

| Cleland et al. [126] | 89 | 190 | 279 | 63 | 74 | < 35 | Warfarin with INR of 2.5 | Aspirin or no antithrombotic therapy | 27 months |

| Cokkinos et al. [129] | 92 | 105 | 197 | 59 | 85 | 28 | Warfarin was supplied as 5-mg tablets. The daily dose was 2.5–10 mg, with a target INR of 2–3 | Placebo | 19.5 months |

| Zannad et al. [265] | 2507 | 2515 | 5022 | 66 | 77 | 34 | Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily | Placebo | 21 months |

| Cohn and Toghoni [128] | 2511 | 2499 | 5010 | 63 | 80 | 27 | Valsartan was initiated at a dose of 40 mg twice daily, and the dose was doubled every 2 weeks until a target dose of 160 mg twice daily was reached | Placebo | 23 months |

| Granger et al. [160] | 179 | 91 | 270 | 66 | 25 | 26 | Candesartan, 4 mg, 8 mg and 16 mg | Matching placebo | 12 months |

| Granger et al. [161] | 1013 | 1015 | 2028 | 66 | 68 | 30 | Candesartan, 4 mg, 8 mg, 16 mg, 32 mg | Matching placebo | 34 months |

| Maggioni et al. [190] | 185 | 181 | 67 | 63 | 71 | 28 | Valsartan | Placebo | 12 months |

| McMurray et al. [197] | N/R | N/R | 7599 | 67 | 40 | 54 | Candesartan | Matching placebo | N/R |

| Spargias et al. [235] | 1734 | 243 | 1977 | 67 | 74 | 40 | Ramipril | Placebo | N/R |

| Sturm [237] | 51 | 49 | 100 | 52 | 90 | 17 | Atenolol | Placebo | 24 months |

| Australia/New Zealand Heart Failure Research Collaborative Group [99] | 208 | 207 | 415 | 67 | 80 | 29 | Carvedilol | Matching placebo | 19 months |

| Beta-Blocker evaluation of survival trial [105] | 1354 | 1354 | 2708 | 60 | 79 | 23 | Initial oral dose of 3 mg of bucindolol, which was repeated twice daily for 1 week | Placebo | 24 months |

| Bristow et al. [114] | 261 | 84 | 345 | 60 | 78 | 23 | Low-dose Carvedilol (6.25 mg BID), medium-dose Carvedilol (12.5 mg BID), and high-dose Carvedilol (25 mg BID) | Placebo | 6 months |

| CIBIS [123] | 320 | 321 | 641 | N/R | N/R | 25 | 2.5 mg Bisoprolol | 2,5 mg placebo | 1.9 years |

| CIBIS-II [124] | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | 28 | Bisoprolol 1.25 mg | Placebo | 1.3 years |

| Colucci et al. [130] | 232 | 134 | 366 | 55 | 86 | 23 | Carvedilol | Placebo | 213 days |

| Dargie [134] | 975 | 984 | 1959 | 63 | 74 | 33 | Carvedilol | Identical looking placebo | 1.3 years |

| Fisher et al. [149] | 25 | 25 | 50 | 63 | 100 | 22 | Metoprolol, from 6.25 to 12.5 mg twice a day to 12.5 mg three times a day to 25 mg twice a day | Placebo | 6 months |

| Goldstein et al. [159] | 40 | 20 | 60 | N/R | N/R | 27 | The initial dose of approximately 12.5 mg Metoprolol (one half of a 25 mg tablet) was administered once daily. The dose of metoprolol was increased to 25 mg and subsequently increased in steps of 50 mg to 100 mg and finally to 150 mg once daily | Matching placebo | 26 weeks |

| Komajda [177] | N/R | N/R | 572 | N/R | N/R | < 40 | Enalapril | Matching placebo | N/R |

| Merit-HF [198] | 1990 | 2001 | 3991 | 64 | 78 | 28 | Metoprolol | Placebo | 1 year |

| Packer et al. [208] | 133 | 145 | 278 | 61 | 73 | 22 | Carvedilol, 25–50 mg BID | Placebo | 6 months |

| Packer et al. [209] | 696 | 398 | 1094 | 58 | 77 | 23 | Carvedilol | Placebo | 6.5 months |

| Packer et al. [210] | 1156 | 1133 | 2289 | 63 | 80 | 20 | Carvedilol | Placebo | 10.4 months |

| van Veldhuisen et al. [248] | 678 | 681 | 1359 | 76 | 70 | 29 | Nebivolol | Placebo | 21 months |

| Di Biase [138] | 102 | 101 | 203 | 74 | 60 | 29 | PVI + LAPWI + SVCI + CFAE | AMIO therapy | 24 months |

| Jones and Wong [173] | 26 | 26 | 52 | 63 | 87 | 22 | PVI + linear then CFAEs | Rate control | 12 months |

| MacDonald et al. [189] | 22 | 19 | 41 | 63 | 78 | 20 | PVI ± linear lesions + CFAEs | Rate control | 6 months |

| Marrouche et al. [192] | 179 | 184 | 363 | 85 | 61 | 32 | PVI + / − additional lesions at discretion of operator | Rate and/or rhythm control | 38 months |

| Prabhu et al. [223] | 33 | 33 | 66 | 91 | 61 | 35 | PVI + LAPWI | Rate control | 6 months |

| DIG [139] | 3397 | 3403 | 6800 | 64 | 78 | 29 | Digoxin | Placebo | 37 months |

| Packer et al. [207] | 85 | 93 | 178 | 61 | 76 | 28 | Digoxin | Placebo | 3 months |

| Uretsky et al. [247] | 42 | 46 | 88 | 64 | 90 | 29 | Digoxin | Withdrawal of digoxin | 3 months |

| Assmus et al. [95] | 24 | 23 | 47 | 61 | 100 | 39–41 | Intracoronary infusion of BMC or CPC | No cell infusion | 3 months |

| Assmus et al. [96] | 64 | 39 | 103 | 65 | 90 | 32–37 | Intracoronary infusion of BMCs | Cell-free medium (placebo) | 45.7 months |

| Bartunek et al. [100] | 32 | 15 | 47 | 59 | 91 | 28 | Patients in the cell therapy arm received bone marrow–derived cardiopoietic stem cells meeting quality release criteria | Standard of care comprising a beta-blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and a diuretic with dosing and schedule tailored for maximal benefit and tolerability in accordance with practice guidelines for heart failure management | 2 years |

| Bolli et al. [111] | 16 | 7 | 23 | 57 | 100 | 30 | Autologous CSCs were isolated from the right atrial appendage and re-infused intracoronarily 4 ± 1 months after surgery; | No treatment | 12 months |

| Hamshere et al. [165] | 15 | 15 | 30 | 56 | 86 | 42 | G-CSF + BMSC | Peripheral placebo (saline) | 12 months |

| Heldman et al. [168] | 22 | 11 | 33 | 60 | 95 | 38–40 | Mesenchymal stem cell group or bone marrow mononuclear cell group | Placebo | 12 months |

| Heldman et al. [168] | 38 | 21 | 59 | 61 | 100 | 36 | Mesenchymal stem cell group or bone marrow mononuclear cell group | Placebo | 12 months |

| Mathiasen et al. [194] | 40 | 20 | 60 | 66 | 90 | 28 | BMSC | Placebo | 6 months |

| Menasché [195] | 63 | 34 | 97 | 61 | 100 | 29 | Cell suspension | Placebo solution consisting of the suspension medium without skeletal myoblasts | 72 months |

| Mozid et al. [203] | 14 | 2 | 16 | 70 | 94 | 31 | G-CSF + BMSC | Placebo | 6 months |

| Patel et al. [212] | 24 | 6 | 30 | 59 | 100 | 26 | BMAC infusion | Standard heart failure care | 12 months |

| Pätilä et al. [213] | 20 | 19 | 39 | 65 | 95 | 37 | Injections of BMMC or vehicle intra-operatively into the myocardial infarction border area | Controls received only vehicle medium by syringes | 12 months |

| Perin et al. [214] | 20 | 10 | 30 | 61 | 80 | 39 | Transendocardial delivery of ABMMNCs | Placebo | 6 months |

| Austin et al. [98] | 100 | 100 | 200 | 60 | 66 | 85% < 35 | An 8-week cardiac rehabilitation program that was coordinated by the clinical nurse specialist. Patients attended classes twice weekly for a period of 2.5 h | Eight weekly monitoring of clinical status (functional performance, fluid status, cardiac rhythm, laboratory assessment) in the cardiology outpatients by the clinical nurse specialist | 8 weeks |

| Belardinelli et al. [101] | 50 | 49 | 99 | 59 | 88 | 28 | The exercise group underwent exercise training for 14 months | The control group did not exercise | 14 months |

| Belardinelli et al. [102] | 63 | 60 | 123 | 59 | 78 | 37 | The trained group underwent an ET program for 10 years. The training program consisted of 3 sessions per week at the hospital for 2 months, then 2 supervised sessions the rest of the year. Every 6 months, patients exercised at the hospital, and then they returned to a coronary club, where they exercised the rest of the year | The nontrained group was not provided with a formal ET program | 120 months |

| Chen et al. [121] | 19 | 18 | 27 | 61 | 36 | 36 | Outpatient cardiac rehabilitation for 1 week, before starting home-based cardiac rehabilitation. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation was conducted by requesting the interventional group to carry out aerobic exercise at least 3 times per week, for a duration of at least 30 min each time | Instructed to maintain both their standard medical care and previous activity levels | 3 months |

| Cowie et al. [131] | 30 | 16 | 46 | 64 | 91 | The hospital group attended a physiotherapist-led class | A DVD and booklet (replicating the class) was created for home use. Controls followed their usual HFNS care | 5 years | |

| Dalal et al. [132] | 107 | 109 | 216 | 70 | 78 | 35 | REACH-HF manual for patients with a choice of two structured exercise programs | No cardiac rehabilitation approach that included medical management according to national and local guidelines, including specialist heart failure nurse care | 12 weeks |

| Ellingsen et al. [147] | 78 | 81 | 261 | 60 | 81 | 29 | HIIT and MCT had 3 supervised sessions per week on a treadmill or bicycle. HIIT included four 4-min intervals aiming at 90 to 95% of maximal heart rate separated by 3-min active recovery periods of moderate intensity. MCT sessions aimed at 60 to 70% of maximal heart rate | Patients were advised to exercise at home according to current recommendations and attended a session of moderate-intensity training at 50 to 70% of maximal heart rate every 3 weeks | 3 months |

| Giannuzzi et al. [156] | 45 | 45 | 90 | 60 | N/R | 25 | The exercise protocol consisted of supervised continuous sessions of 30-min bicycle ergometry > 3 times a week (3 to 5 times) at 60% of the peak V˙ O2 achieved at the initial symptom-limited exercise testing. In addition to supervised sessions, patients were asked to take a brisk daily walk for > 30 min and intermittent unsupervised sessions of calisthenics (30 min) as part of the home-based exercise program | Educational support, but no formal exercise protocol | 6 months |

| Hambrecht et al. [163] | 12 | 10 | 22 | 52 | 27 | 26 | Patients assigned to the training program remained in an intermediate care ward for the initial 3 weeks. Training sessions were conducted individually under strict supervision for the first 3 weeks. Patients exercised six times daily for 10 min on a bicycle ergometer | Patients assigned to the control group spent 3 days in an intermediate care ward for baseline evaluation. After discharge, medical therapy was continued, and patients were supervised by their private physicians | 6 months |

| Hambrecht et al. [164] | 36 | 37 | 73 | 54 | 100 | 27 | 2 weeks of in-hospital ergometer exercise for 10 min 4 to 6 times per day, followed by 6 months of home-based ergometer exercise training for 20 min per day at 70% of peak oxygen uptake | No intervention | 6 months |

| Jolly et al. [172] | 84 | 85 | 169 | 66 | 75 | < 40 | Three supervised exercise sessions to plan an individualized exercise program. These were followed by a home-based program, with home visits at 4, 10, and 20 weeks, telephone support at 6, 15, and 24 weeks, and a manual with details about safe progressive exercise and self-monitoring of frequency, duration, and intensity | Specialist heart failure nurse input in primary and secondary care through clinic and home visits that included the provision of information about heart failure, advice about self-management and monitoring of their condition, and titration of beta-blocker therapy | 3 months |

| Mueller et al. [204] | 25 | 25 | 50 | 55 | 100 | < 40 | Five indoor cycling sessions were performed weekly for a duration of 30 min, and all subjects walked outdoors for 45 min twice daily. Training duration was one month | Control subjects received usual clinical care, including verbal encouragement to remain physically active | 1 month |

| Passino et al. [211] | 44 | 41 | 85 | N/R | N/R | 35 | The training group underwent a nine-month training program. The training program consisted of cycling on a bike for a minimum of 3 days per week, 30 min per day | Control patients continued their usual lifestyle | 9 months |

| Willenheimer et al. [258] | 27 | 27 | 54 | N/R | N/R | 35 | Patients carried out cycle ergometer interval training at a heart rate corresponding to 80% of peak-VO2 ± 5 beats/min, for as long as possible during each interval | Control patients were asked not to change their degree of physical activity during the active study period | 6 months |

| Abraham et al. [87] | 228 | 225 | 453 | 64 | 68 | 22 | Atrial-synchronized biventricular pacing | No pacing for six months, during which time medications for heart failure were to be kept constant | 6 months |

| Abraham et al. [88] | 101 | 85 | 186 | 64 | 89 | 25 | Optimal medical treatment with active CRT and active ICD therapy | Optimal medical treatment and active ICD therapy | 6 months |

| Bentkover et al. [104] | 36 | 36 | 72 | 79 | 79 | < 35 | Biventricular pacing and ICD | ICD alone | 6 months |

| Cazeau et al. [118] | 29 | 29 | 58 | 63 | 75 | 23 | Atriobiventricular (active) pacing | Ventricular inhibited (inactive) pacing | 3 months |

| Chung [122] | 9 | 9 | 18 | 76 | 76 | 30 | A CRT–defibrillator device with LV coronary venous lead system | A dual-chamber ICD | 12 months |

| Daubert et al. [135] | 82 | 180 | 262 | 81 | 81 | 28 | Patients who had undergone successful implantation were randomly assigned in a 2-to-1 scheme to a CRT ON group for 24 months | CRT OFF | 24 months |

| Gasparini et al. [153] | 33 | 36 | 69 | 67 | 94 | 26 | BiV CRT | LV | 12 months |

| Higgins et al. [169] | 245 | 245 | 490 | 66 | 84 | 22 | CRT-D | ICD | 6 months |

| Linde et al. [183] | 25 | 18 | 43 | 66 | 84 | 30 | Biventricular VVIR pacing during two 3-month periods | Right-univentricular VVIR pacing during two 3-month periods | 3 months |

| Leclercq et al. [184] | 25 | 19 | 44 | 74 | 100 | 27 | Biventricular VVIR pacing during two 3-month periods | Right-univentricular VVIR pacing during two 3-month periods | 3 months |

| Linde et al. [185] | 419 | 191 | 610 | 79 | 79 | 27 | Active CRT | Control | 12 months |

| Martinelli et al. [193] | 27 | 27 | 54 | 59 | 68 | 30 | Device was initially programmed to BiVP, crossed to RVP and crossed back to BiVP | Device was initially programmed to RVP, crossed to BiVP and crossed back to RVP | 18 months |

| Moss et al. [201] | 742 | 490 | 1232 | 65 | 85 | 23 | ICD | Conventional medical therapy | 20 months |

| Moss et al. [202] | 1089 | 731 | 1820 | 75 | 75 | 24 | Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with biventricular pacing | ICD alone | 2.4 years |

| Piepoli et al. [217] | 44 | 45 | 89 | 72 | 72 | 24 | CRT-P/CRT-D | Medical | 12 months |

| Pinter et al. [218] | 36 | 36 | 72 | 79 | 79 | 23 | CRT-D | ICD | 6 months |

| Pokushalov et al. [221] | 91 | 87 | 178 | 90 | 90 | 29 | CRT-P + CABG | CABG | 18 months |

| Pokushalov et al. [222] | 13 | 13 | 26 | 96 | 96 | 27 | BMMC + active CRT | BMMC + inactive CRT | 6 months |

| Ruschitzka et al. [226] | 404 | 405 | 809 | 72 | 72 | 27 | CRT capability turned on | CRT capability turned off | 19.4 months |

| Tang et al. [240] | 894 | 904 | 1798 | 83 | 83 | 23 | ICD + CRT | ICD alone | 40 months |

| Thibault et al. [242] | 60 | 61 | 121 | 75 | 75 | 24 | biventricular CRT | LV CRT | 6 months |

| Thibault et al. [243] | 44 | 41 | 85 | 71 | 71 | 25 | CRT-D | ICD | 12 months |

| Young et al. [262] | 182 | 187 | 369 | 68 | 78 | 24 | Combined CRT and ICD capabilities | ICD activated, CRT off | 6 months |

| Fragasso et al. [151] | 34 | 31 | 65 | 65 | 96 | 35 | Trimetazidine, 20 mg three times daily | Placebo | 13 months |

| Rosano et al. [225] | 16 | 16 | 32 | 66 | 75 | 33 | 20 mg t.d.s. trimetazidine | Placebo t.d.s | 6 months |

| Tuunanen et al. [245] | 12 | 7 | 19 | 58 | 79 | 34 | Trimetazidine | Placebo | 3 months |

| Vitale et al. [252] | 23 | 24 | 47 | 78 | 85 | 29 | Trimetazidine | Placebo | 6 months |

| Margulies et al. [191] | 154 | 146 | 300 | 62 | 69 | 25 | Liraglutide | Placebo | 6 months |

| Fox et al. [150] | 5479 | 5438 | 10,917 | 60 | 83 | 32 | Ivabradine 7.5 MG BID | Placebo | 19 months |

| Swedberg et al. [238] | 3241 | 3264 | 6505 | 65 | 76 | 29 | Ivabradine 7.5 MG BID | Placebo | 22.9 months |

| Asgar et al. [94] | 50 | 42 | 92 | 75 | 77 | 38 | Treated with the MitraClip | This retrospective comparator group consisted of medically managed patients | 22–33 months |

| Giannini et al. [155] | 60 | 60 | 120 | 76 | 70 | 34 | MitraClip | Optimal medical therapy | 17 months |

| Obadia et al. [206] | 152 | 152 | 304 | 71 | 79 | 33 | Percutaneous mitral-valve repair | medical therapy alone | 12 months |

| Stone et al. [236] | 302 | 312 | 614 | 73 | 67 | 31 | Transcatheter mitral-valve repair plus medical therapy | Medical therapy alone | 16.5 months |

| Boccanelli et al. [109] | 188 | 193 | 381 | 63 | 84 | 40 | Canrenone | Placebo | 12 months |

| Chan et al. [120] | 23 | 25 | 48 | 63 | 83 | 27 | Candesartan 8 mg and spironolactone 25 mg once daily | Candesartan 8 mg and a matching identical placebo once daily | 12 months |

| Cicoira et al. [125] | 54 | 52 | 106 | 67 | 86 | 33 | Spironolactone treatment, at an initial dose of 25 mg once daily | Placebo | 12 months |

| Pitt et al. [219] | 822 | 841 | 1663 | 65 | 73 | 25 | Spironolactone, 25 mg | Matching placebo | 24 months |

| Pitt et al. [220] | 3319 | 3313 | 6632 | 64 | 71 | 33 | Eplerenone | Placebo | 16 months |

| Udelson et al. [246] | 116 | 109 | 225 | 63 | 84 | 27 | Eplerenone, 50 mg/d | Placebo | 9 months |

| Vizzardi et al. [253] | 65 | 65 | 130 | 65 | N/R | 36 | 25 mg of spironolactone once daily | Matching placebo | 44 months |

| Zannad et al. [264] | 1364 | 1373 | 2737 | 69 | 78 | 26 | Eplerenone 50 mg/d | Placebo | 21 months |

| Atienza et al. [97] | 164 | 174 | 338 | 68 | 60 | 36 | 1 individual session prior to discharge by nurse, 1 visit to physician, 3-monthly follow-up visits and tele-monitoring | Usual care (discharge planning according to protocol) | 509 days |

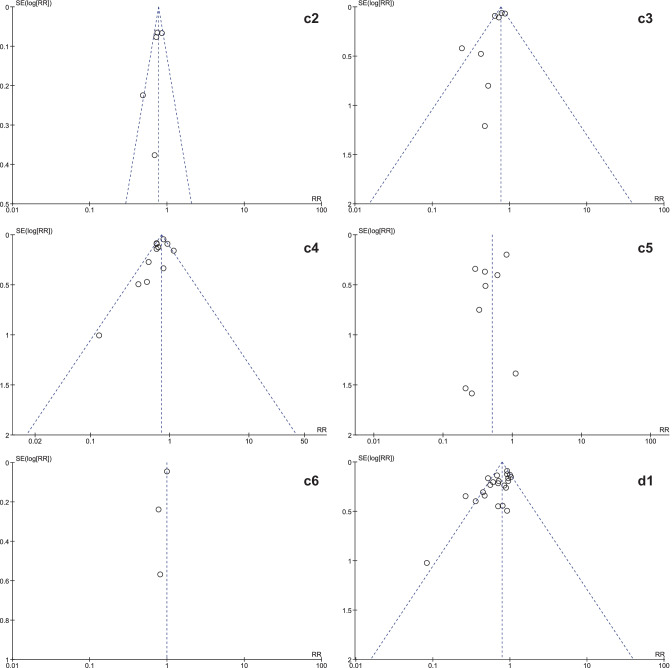

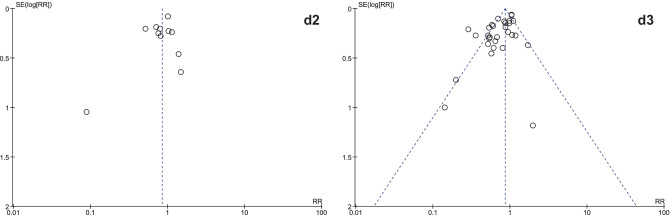

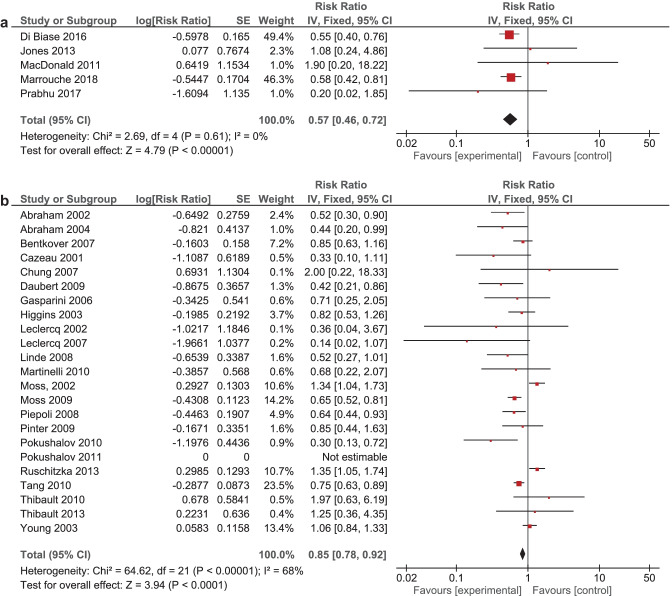

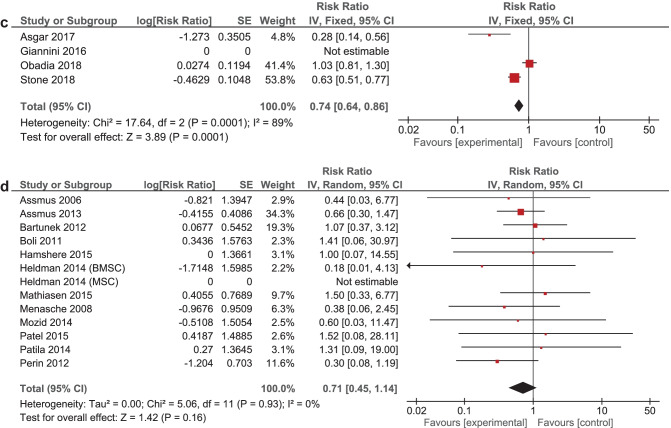

| Blue et al. [108] | 84 | 81 | 165 | 75 | 48 | Severe 40% | Planned home visits of decreasing frequency, supplemented by telephone contact as needed. The aim was to educate the patient about heart failure and its treatment, optimize treatment (drugs, diet, exercise), monitor electrolyte concentrations, teach self-monitoring and management, liaise with other health care and social workers as required, and provide psychological support | Patients in the usual care group were managed as usual by the admitting physician and, subsequently, general practitioner. They were not seen by the specialist nurses after hospital discharge | 12 months |