Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Young adults have the highest rates of substance use of any age group. Although men historically have higher rates of substance use disorders (SUDs) than women, research shows this gender gap is narrowing. Young adults with comorbid psychiatric disorders are at increased risk for developing an SUD. Co-occurring psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, eating and post-traumatic stress disorders are more prevalent in women than men with SUDs, yet mental health treatment often does not adequately address substance use in patients receiving care for a comorbid psychiatric disorder. Tailored gender-responsive interventions for women with psychiatric disorders and co-occurring SUD have gained empirical support. Digital interventions tailored to young adult women with co-occurring disorders have potential to overcome barriers to addressing substance use for young adult women in a psychiatric treatment setting. This study utilized a user-centered design process to better understand how technology could be used to address substance use in young adult women receiving inpatient and residential psychiatric care.

METHODS:

Women (N = 15; age 18–25 years), recruited from five psychiatric treatment programs, engaged in a qualitative interview and completed self-report surveys on technology use and acceptability. Qualitative interviews were coded for salient themes.

RESULTS:

Results showed that few participants were currently using mental health web-based applications (i.e., “apps”), but most participants expressed an interest in using apps as part of their mental health treatment. Participants identified several important topics salient to women their age including substance use and sexual assault, stigma and shame, difficulties abstaining from substance use while maintaining social relationships with peers, and negative emotions as a trigger for use.

CONCLUSIONS:

These data provide preliminary evidence that a digital intervention may be a feasible way to address co-occurring substance use problems in young adult women receiving care in a psychiatric setting.

Keywords: women, co-occurring disorders, substance use disorders, technology, young adults

Young adults (usually defined as age 18–25 years) have higher rates of substance use than any other age group (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020), with 39.1% of young adults reporting past year illicit drug use compared to 17.2% of adolescents (ages 12–17 years), and 18.3% of adults 26 years or older (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Moreover, marijuana use is increasing in young adults, such that in 2002 those reporting past year marijuana use was 29.8% and in 2019 that percentage has risen to 35.4% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Although young adults had similar rates of past month alcohol use as adults age 26 or older (54.3% and 55%, respectively), young adults had higher rates of binge-drinking (34.3%) compared to adults (24.5%, (Schulenberg et al., 2019; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020).

Compared with men, women average more medical, psychiatric, and social consequences of substance use (Greenfield, Back, Lawson, & Brady, 2011). For example, because women absorb and metabolize alcohol differently than men, they are more susceptible to the negative physical consequences of alcohol, including liver disease, heart disease, and brain damage (Ait-Daoud et al., 2019). In addition, women in treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs) report more severe impariment in psychiatric functioning and poorer overall quality of life than men (McHugh, Votaw, Sugarman, & Greenfield, 2018). There are higher rates of eating disorders in women with SUDs compared ot the general population, and trauma, mood and anxiety disorders are more prevalent in women with SUDs than men with SUDs (Greenfield et al., 2011). Although men historically have higher rates of SUDs than women, research shows that this gender gap is narrowing (McHugh et al., 2018; Steingrimsson, Carlsen, Sigfusson, & Magnusson, 2012), particularly among adolescents (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Moreover, gender differences in illicit drug use are smaller in non-college aged youth when compared to college aged students (Miech et al., 2020; Schulenberg et al., 2019). In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention labeled binge drinking among girls and women as a “serious, under-recognized problem” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013).

Young adults with comorbid psychiatric disorders are considered to be at high risk for developing an SUD (Bukstein, 2017). There are also gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity, with higher rates of anxiety, depression, and eating disorders in women compared to men (Conway, Compton, Stinson, & Grant, 2006; Riecher-Rössler, 2017). Women are also more likely to experience a traumatic event and posttraumatic stress disorder prior to the onset of an SUD (Compton et al., 2000; Khoury, Tang, Bradley, Cubells, & Ressler, 2010; Sonne, Back, Diaz Zuniga, Randall, & Brady, 2003). Empirically-based integrated treatments that address comorbid disorders simultaneously are recommended, but are limited in availability and accessibility to patients (Yule & Kelly, 2019). Historically, mental health and substance use treatment have operated as discrete entities (Lichtenstein, Spirito, & Zimmermann, 2010). Limited training, resources, and support have been cited as barriers to treating co-occurring substance use problems in mental health treatment settings (Padwa, Guerrero, Braslow, & Fenwick, 2015). Asynchronous digital interventions (e.g., mobile apps, internet-based programs, text messaging interventions) have the potential to address some of the treatment challenges of comorbidity by providing an easily accessible, cost-effective alternative to in-person services. Moreover, these types of interventions do not rely on clinician-led services, which may help fill the widening gap between mental health demand and inadequate capacity of mental health clinicians (Gardner, Plaven, Yellowlees, & Shore, 2020), which is a key challenge for addressing mental health in young people (Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007). Digital interventions may be particularly appealing to young adults as data show that individuals aged 18–29 have the highest rates of internet use and smartphone ownership in the US (Pew Research Center, 2019), and children and young people report moderate to high satisfaction with digital interventions for mental health (Hollis et al., 2017).

Digital mental health interventions for young adults have focused mostly on college student and adolescent samples, with evidence for improving depression and anxiety (Grist, Croker, Denne, & Stallard, 2019; Lattie et al., 2019) and reduced substance use (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliott, Bolles, & Carey, 2009; Gulliver et al., 2015; Leeman, Perez, Nogueira, & DeMartini, 2015; Ondersma, Ellis, Resko, & Grekin, 2019). Differences in mental health severity and substance use between college students and non-college attending young adults have been noted. In particular, non-college attending young adults have a higher risk of attempting suicide with a plan, and are more likely to have a drug use disorder and nicotine dependence compared to college students (Blanco et al., 2008; Han et al., 2016). Therefore, it is important to expand research with young adults in this area to include both college students and non-college attending peers.

The bulk of research on digital interventions targeting substance use in young adults has focused on university settings, emergency departments, and primary care clinics (Marsch & Borodovsky, 2016). The psychiatric treatment setting also provides an opportunity to intervene. A recent pilot study found support for the acceptability of a web-based program aimed at reducing substance use in adults with co-occurring disorders receiving inpatient psychiatric care (Hammond, Antoine, Stitzer, & Strain, 2020). However, few digital interventions have specifically addressed substance use and psychiatric comorbidity, particularly in young adults (Holmes, van Agteren, & Dorstyn, 2019; Sugarman, Campbell, Iles, & Greenfield, 2017). One study of an online intervention for young adults with problematic alcohol use and depression found short-term improvements in depression and reductions in alcohol use (Deady, Mills, Teesson, & Kay-Lambkin, 2016). Young adults face unique challenges in navigating the transition from childhood to adulthood without having yet achieved the cognitive maturity of adulthood (Wilens & Rosenbaum, 2013) and young women are a particularly vulnerable group, with gender-specific needs. Given the dearth of research in digital interventions for young adult women with substance use and co-occurring psychiatric disorders, the aims of this study were to (a) characterize current technology and mental health application (app) use in a sample of young adult women with substance use problems receiving inpatient or residential psychiatric treatment, (b) understand the gaps in treatment for addressing substance use in young adult women with co-occurring disorders, and (c) explore how technology could enhance current mental health treatment for these women.

METHODS

Participants

Women were recruited for the study from five psychiatric treatment programs (2 inpatient and 3 residential) that treat eating disorders, trauma, depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder at a psychiatric hospital. Inpatient programs focus on crisis stabilization when there is risk of harm to self or others and provide 24-hour nursing supervision and care in a secure setting. Residential programs are geared toward patients who are medically stable, need intensive treatment, but are not at immediate risk of harm to self or others. Typical length of stay is 4–7 days for inpatient treatment and 2–6 weeks for residential treatment. Women were eligible for this study if they were (a) 18–25 years of age, and (b) identified as having problems with substance use, as determined by review of medical record or by treating clinician. Participants were excluded if they were (a) unable to sign the informed consent, (b) unwilling to engage in the individual interview, and/or (c) had another clinical condition that prevents their engagement in study procedures, such as severe cognitive impairment.

Twenty-one women were eligible for the study and 15 were enrolled. Two women were discharged before study staff could meet with them, and four were not interested in participating in the research study.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, treatment program, and reason for current admission were assessed prior to the qualitative interview.

Substance use

Substance use was measured using a brief, 7-item questionnaire developed for this study, which includes questions on lifetime use, current use, and treatment history.

Technology use/acceptability

Technology use/acceptability was measured using a modified version of the Smartphone Use Survey (Beard et al., 2019). This 8-item questionnaire assessed smartphone ownership, web-based application (i.e., “app”) usage, and interest in using apps to support mental health.

Qualitative semi-structured interviews

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the treatment needs of young adult women with co-occurring substance use and examine how technology could be used to enhance current mental health treatment for these women (see Supplemental File A).

Procedures

The protocol for this study received approval from Mass General Brigham (formerly Partners HealthCare) Institutional Review Board; participants completed an informed consent process which involved a complete discussion of the study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Women who enrolled in the study completed brief questionnaires prior to engaging in the individual qualitative interview. Participants received a $25 gift card for their participation in the study.

All interviews were conducted by the Principal Investigator (PI; DES), audio-recorded, and then transcribed and coded using inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) in NVivo 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2015). Following the six phases outlined by Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clarke, 2006), the PI (DES) and research assistant (RA; LEM) independently reviewed the transcripts, generated initial codes and then examined the codes to identify themes. The PI and RA met to review the themes and either differentiated them further or grouped them according to commonalities. The themes were then refined and named.

RESULTS

Demographic and substance use

The majority of the sample was White and well-educated, with an average age of 22 years (see Table 1). Nine participants (60%) were engaged in residential treatment programs and six (40%) were engaged in inpatient treatment programs. Alcohol was the substance most frequently reported as problematic for participants in the past year, followed by cannabis. In addition to substance use, participants reported a wide range of co-occurring mental health problems in the past year, with depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder being the most common. Only two participants (13%) reported that they had ever received treatment for alcohol or drug problems; however, nearly half (n = 7, 47%) had attended a mutual help group.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Total Sample (N =15) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 21.8 (2.8) |

| range | 18–25 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 13 (86.7) |

| Black/African American | 1 (6.7) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (6.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (13.3) |

| Sexual Orientation, n (%) | |

| heterosexual/straight | 7 (46.7) |

| bisexual | 5 (33.3) |

| lesbian | 2 (13.3) |

| queer | 1 (6.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| high school | 3 (20.0) |

| some college | 9 (60.0) |

| college | 2 (13.3) |

| postgraduate | 1 (6.7) |

| Currently enrolled as a student, n (%) | 7 (46.7) |

| Mental health problems endorsed in the past year, n (%) | |

| depression | 15 (100.0) |

| anxiety | 15 (100.0) |

| substance use | 15 (100.0) |

| eating disorder | 7 (46.7) |

| posttraumatic stress disorder | 6 (40.0) |

| borderline personality disorder | 5 (33.3) |

| obsessive compulsive disorder | 3 (20.0) |

| bipolar disorder | 3 (20.0) |

| Currently use tobacco/nicotine products, n (%) | 7 (46.7) |

| Substances that have caused the most problems, past year, n (%) | |

| alcohol | 13 (86.7) |

| cannabis | 6 (40.0) |

| sedatives | 2 (13.3) |

| hallucinogens | 1 (6.7) |

| stimulants | 1 (6.7) |

| tobacco | 1 (6.7) |

Technology use

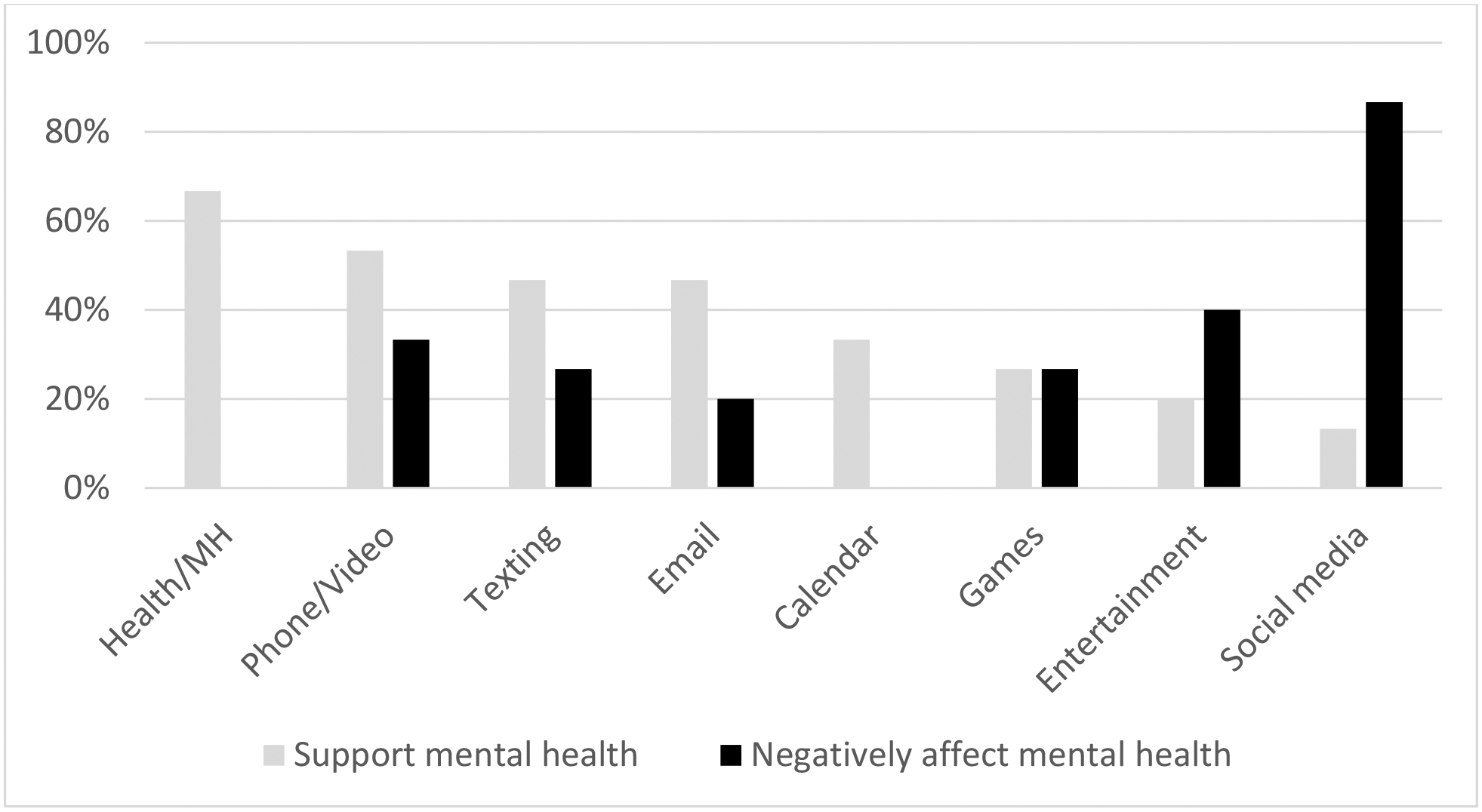

Fourteen participants (93%) indicated that the primary device that they use to access the internet was their smartphone, with one participant (7%) reporting that she primarily uses a computer to access the internet. The most frequently used smartphone apps were texting and social media apps (see Table 2). The apps most frequently endorsed as being supportive of mental health were health and mental health apps, phone/video apps, and texting apps (see Figure 1). However, participants reported infrequent use of health and mental health apps. Entertainment apps and social media apps were rated as having a negative effect on mental health.

Table 2.

Frequency of Web-based App Use

| Type of App | Never n (%) | Rarely n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Frequently n (%) | Often n (%) | Very often n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texting apps (e.g., Messenger, WhatsApp) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 11 (73.3) |

| Phone/video apps (e.g., Skype, FaceTime) | 0 | 4 (26.7) | 4 (6.7) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) |

| Email apps (e.g., Outlook, Gmail) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 5 (33.3) |

| Social media apps (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 4 (26.7) | 10 (66.7) |

| Calendar apps | 0 | 3 (20.0) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) |

| Entertainment apps (e.g., Podcasts, YouTube) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| Games | 5 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Health and mental health apps | 5 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

Figure 1.

Participant Ratings of the Effect of Smartphone Apps on their Mental Health

Over half of the sample (n = 8, 53%) reported using 1–2 mental health apps on their primary device. The most common types of mental health apps were meditation/mindfulness (n = 8, 53%) and mood tracking apps (n = 3, 20%). Only two participants (13%) said they would not want to use a web-based program as part of their mental health treatment.

Qualitative Results

Four key themes emerged from the qualitative interviews: (1) gaps in current treatment, (2) important topics to address, (3) technology solutions, and (4) technology preferences. Illustrative quotes are listed in the text below, and additional quotes for each theme are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Qualitative Quotes

| Subtheme | Quote (Age, Level of Care) |

|---|---|

| THEME: GAPS IN CURRENT TREATMENT | |

| Substance use not adequately addressed in current treatment | “I go to the groups and stuff but they don’t really talk about substances or anything, so I mean I wouldn’t say it’s something that I get a lot of help with.” (23, inpatient) |

| “…there’s lots of other things that are covered, and not everybody struggles with it so, it’s not brought up as often in group or that kind of thing.” (18, residential) | |

| “I have two therapists that I’ve been seeing, but we discussed [substance use] briefly but that’s not the focus of the treatment. I guess my hope when I came in here is that there would be more options for individual-based like substance abuse treatment.” (25, inpatient) | |

| Lack of integrated treatment | “I would say there isn’t like a huge – I guess there’s not a huge emphasis on [substance use]…I mean obviously we’re here for eating disorders, but, there’s only so many times you can meet with your individual therapists and so much of that is with mood and body image.. so in the groups it’s kind of challenging as well because you talk about it in a more generalized sense…so I would say that that’s kind of something that’s, like a little bit challenging is not being able to talk about [substance use] in direct connection with my feelings and my treatment specifically.” (24, residential) |

| “I have to kind of seek help on my own, like, individually…which can be difficult and intimidating, so sometimes I just kind of sit with it… it’s been kind of strange breaking it down, figuring out whether or not, hallucinations are from drug use or mental health issues –it’s kind of, it’s been a process, figuring it out alone.” (18, residential) | |

| THEME: IMPORTANT TOPICS TO ADDRESS | |

| Sociocultural issues | “I feel like, like peer pressure almost, has a lot to do with it. Um, just a lot of stresses that females like, I feel go through that men don’t.” (23, inpatient) |

| “Cause a lot of people drink in college. And just like the stereotype around it. I’m young so it’s expected that I’m just going to drink and have a good time, but, when you’re not always in the best mental state, it’s not the best thing to do.” (19, residential) | |

| Age-related reasons for use | “I haven’t even turned 21 yet and so everybody my age drinks. Even my friends that don’t - like some of my friends do struggle with substance abuse, both alcohol and not alcohol - and being around them is really difficult obviously, but then even my friends that don’t have any abuse of substances, it’s still difficult to be around because they still do drink and it is such like a social and cultural thing.” (20, residential) |

| “they kept on bringing up the word ‘abstinence’ and it really freaked me out because I’m 24, I want to be able to go out and have a beer with my friends” (24, inpatient) | |

| Gender-related issues | “Specifically for women I think that like, I’m not enough. I have too much to take care of all the time. I have so many roles and responsibilities that I don’t feel like I’m allowed to talk about or, ask for help with, then turning to substance use seems pretty natural.” (19, residential) |

| “Hormone fluctuations, that would be a really big one – cause I do notice that I tend to drink more glasses of red wine right before my period.” (25, inpatient) | |

| “I also think that substance use in women is pathologized in ways it’s not in men…it’s just like men have traditionally been allowed to go after work and let off some steam with the boys and drink and that’s not a problem necessarily unless something serious, like they can no longer support their family, whereas a woman is oftentimes seen as selfish or deemed as like unfit or as having a problem really quickly. Which I don’t think is to say that that person doesn’t have a problem, but it’s just like it’s looked at with this different lens.” (19, residential) | |

| Connection between substance use and co-occurring disorder(s) | “How it’s related to eating disorders –how they coincide, I guess. ..I think they kind of feed off each other, so yeah, it’s important to – cause I feel like when I’m bad with one, it’s probably, it like makes me bad with the other one as well, so I think I need for both to just stop for it to be better for me.” (25, residential) |

| “I was reading an article about how it’s just extra difficult if you have mental illness and addiction or like trauma and addiction, it’s harder to deal with, so I think maybe in some ways yeah I would kind of like to see a connection and see why – and maybe realize like why that led to that.” (24, inpatient) | |

| THEME: TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS | |

| Coping skills | “…grounding skills or anything like that – those are really helpful in the apps.” (23, inpatient) |

| “one other thought I had –what about, um, the importance of having information or skills, particularly focused on the interaction of substance use and depression or anxiety and how those co-occur and affect each other?” (25, inpatient) | |

| “I know some apps have like breathing techniques or like grounding techniques – so maybe like incorporating that would be useful, like if somebody was having really high urges and couldn’t ground themselves, like to use, having something that would help you go through that process of grounding, may be really helpful.” (20, residential) | |

| Tracking substance use and mental health symptoms | “Maybe have something in terms of like a way to track or follow goals…for instance if you want to start by cutting back and, you know, set a goal in tracking things and maybe tracking other aspects of health to see how they maybe, possibly correlated with substance abuse.” (25, inpatient) |

| “…we have this thing called a diary card –you probably know the concept –and, having an online or I don’t even know tech – pixelated diary card…I don’t think I would feel more inclined to use it than my paper one, but you could have more options, you know, it could be logged in, like there could be a bigger archive and you could draw more generalized conclusions about patterns of behavior if they were all on the same server.” (19, residential) | |

| “I think maybe a way to track both time of day and how I’m feeling and just like how distressed I am and why I think I need to use [substances]. And see patterns. Cause I’m a pretty logical person –if I could see it all laid out like ‘oh every time I like come home from school or something I need to smoke.’” (24, inpatient) | |

| Support/peer component | “I think this information is pretty easily accessible online, but maybe to have some sort of location services that can help you locate nearby, like AA or SMART Recovery – or different treatment options if you want to, you know, go to somewhere in person. To have something kind of all in one place so that you know, you don’t have to go to like five different websites, and, can just kind of have one-stop-shop kind of-kind of a thing.” (25, inpatient) |

| “Maybe having it somehow be able to reach out for support in your area especially, like meetings in your area or treatment programs or a health professional you can contact or something like that, I think would be super helpful.” (24, residential) | |

| “I think maybe getting some education behind the different types of meetings -- or like a list of meetings that you can maybe look up on an app, would be helpful.” (20, residential) | |

| Reminder of goals | “Maybe some kind of technology that offers alternatives, that you know, assessing, ‘oh I’m doing this, you know, what is it that I really want here?’ Cause say, if I’m going out at night and I think, ‘oh yeah I just want to do all this drinking’ and I need to think like, you know ‘what do I really want?’ I want to be able to socially connect with people and make sure that I have a lot of fun and I have to think back on all the other times I’ve tried doing this and it’s like, ‘oh, you know every time you do this you make yourself miserable, it turns out horribly.’” (22, residential) |

| “I think, especially with people who have substance abuse, you can tend to dip in and out of responsibilities, so I think having a reminder or a notification pop up would be probably crucial.” (20, residential) | |

| THEME: TECHNOLOGY PREFERENCES | |

| Mobile phone accessible | “I had an app where it’s kind of like everything was in one place, I would – I would definitely use it.” (19, residential) |

| “…not necessarily an app – but more like, like mobile-friendly would probably be helpful…I’m not necessarily in front of my computer all the time but I always have my phone.” (22, residential) | |

| Engagement with technology | “I think it’d actually be very helpful because sometimes if, you know, in certain situations you can’t make it to a group, or you can’t make it to therapy, or doctor’s appointment, you’ll have something you use every day, constantly.” (23, inpatient) |

| “I don’t envision it as something that I open up the app and then sit there for an hour on it at a time, I would’ve envision it as more of something that, you know, you can open up and use for a couple minutes throughout the day, as you want, maybe more than a couple minutes, but, yeah something that’s that easy to access on my phone.” (25, inpatient) | |

| Visual appearance | “I actually enjoy reading. So, I don’t mind either one. I don’t want to sit there for hours watching a video that I could have read in like 2 minutes, you know? So I personally would prefer more text.” (23, inpatient) |

| “I kind of like when there’s a video and then it’s like a recap in the text.” (25, inpatient) | |

| “I personally am really visual learner and it is much more helpful for me to hear things, but I’m also dyslexic so it’s hard for me to read. But I think probably having a balance of both would be important. Especially for distress tolerance skills, like if somebody is having urges and that’s what they’re using it for, I think it would probably be important for it to be maybe mainly visual cause I know a lot of people have a hard time reading stuff when they’re not completely grounded.” (20, residential) | |

| “I think it’s important that it is up-to-date looking.” (24, inpatient) | |

| Interactivity | “I think the interaction like would be fairly important because, I mean it’s hard, it’s like speaking to someone, like having feedback and input definitely is helpful – so something that could emulate that interaction a little bit.” (18, residential) |

| “if you could customize– like our distress tolerance, our skill cards are like a whole thing, but if you could narrow it down to these help me in this situation, like put that in a folder or something that would be helpful, which obviously you need to be able to customize.” (19, residential) | |

Gaps in current treatment.

Two-thirds (n =10) of participants mentioned ways in which their substance use was not adequately addressed in their current treatment.

“I don’t feel as supported when talking about urges…cause it’s not like everybody in here has substance abuse.”

One-third (n = 5) of the participants described a lack of integrated treatment addressing both their substance use and co-occurring psychiatric disorder.

“I’m clearly addicted. And I think it’s a huge part of PTSD…but that’s not really addressed in any of the classes or anything.”

Most participants (n = 14, 93%) said that when substance use was addressed in their current treatment, it was done so in their individual sessions with treatment providers.

Important topics to address.

Participants discussed several topics that they felt were important for young adult women with co-occurring disorders. The most commonly discussed topics were:

sociocultural issues, such as social pressures and expectations, and availability of substances: “alcohol is definitely very accessible and encouraged… it’s just, it’s really easy in general to like access things like alcohol – like I can go on my phone and open up an app, and have something delivered here in under an hour.”

age-related reasons for use, including substance use in college: “It is really really difficult to learn how to integrate being social and being sober at the same time. When everybody my age is drinking or doing that, [it] might not be abuse, but still overusing.” Several comments focused around the normalization of substance use in young adults, and concerns with trying to abstain from substances in the college environment.

gender-related issues, such as sexual abuse and trauma, stigma of women with SUDs, and feelings of shame: “I think there’s a lot of mental health issues that drive substance use that are specifically more common in women – I think it’s this feeling of ‘I’m not enough.’” Many of these comments focused on gender differences in the cultural norms and expectations around substance use. Other comments reflected on biological differences, such as urges to use during hormonal fluctuations.

the connection between substance use and their co-occurring disorder(s): “it’s hard to treat all of my other issues when there’s substance abuse in the background…that would be helpful to look at substance abuse in connection with my other psychiatric and medical conditions.” This theme also came up several times in relation to technology solutions (described below), with many participants expressing an interest in having a way to simultaneously track mental health symptoms and substance use.

Technology solutions.

Participants described many benefits to using technology as part of their treatment including, (1) the ability to be more open and honest about substance use when engaging with a technology-based program, (2) having an extension to treatment (i.e., when you are not in the treatment environment), (3) sharing information with treatment providers, and (4) keeping individuals accountable to their treatment goals. Many participants (n = 11, 73%) described ways to incorporate technology into their inpatient or residential treatment:

“I think online is just easier to type things – type about yourself – instead of like talk about yourself. I think providers could get a lot more information out of a lot of people online.”

“I would probably want it [data from technology program] shared with my treatment team. I think that they can draw a lot more lines and connect certain things that I just can’t because I’m so directly in the situation and they can see it from another perspective.”

One participant expressed a preference for having a program that could be used separately from treatment:

“I understand the importance of collaborating with other treatment providers, but yeah it would be nice to have something that’s kind of just this stand-alone thing, and you know, not that my treatment team couldn’t know that I was using it, but I don’t know if I necessarily feel like it would be important for them to know every single detail of it.”

A few participants (n = 3, 20%) expressed concerns about technology-based programs, describing technology use as isolating, disconnected from reality, and “easier to brush off” than face-to-face treatment. One participant noted an increase in anxiety when using technology, “the day-to-day aspects of technology really exacerbate a lot of the anxieties and I just hate it, I really hate it. I hate the way I feel when I’m on my phone and I’m glad that I’m able to recognize that a lot of anxieties are exacerbated by being on the computer and being on social media.” Despite these concerns, all three of these participants also discussed benefits of technology-based programs as well, particularly when the technology was linked to specific treatment activities, such as learning coping skills or completing diary cards.

Participants generated several ideas for potential components of a digital intervention, including:

Coping skills practice, including grounding skills, breathing techniques, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) skills, and coping with urges: “If I were to go to a party, I have to bring my skill cards and pros and cons list all in my pocket – to have them on an app would be really helpful…people aren’t going to question you being on your phone.”

Tracking substance use and mental health symptoms: “A way to track both time and day and how I’m feeling and how distressed I am…why I think I need to use [substances].” One participant expressed an interest in tracking alcohol use in relation to her menstrual cycle and related mood symptoms.

Support/peer component, such as connecting with others who have similar symptoms, or connecting with mutual-support meetings: “I think it’d be nice to have that option [connecting with peers] in order to just be able to see other people having the same issues.”

Reminder of goals: “I think just having anything to remind me that I’m supposed to be clean – and I want to be – is helpful, like once I’m out of [treatment]- just having something like that like could definitely be that reminder.”

Technology preferences.

More than half of participants (n = 9, 60%) expressed interest in using a program that could be accessed through their mobile phone, and 53% (n = 8) of participants indicated that they would engage with a technology-based program daily or weekly. Regarding the format of the program, participants were interested in a combination of text, videos, and photos, and most felt the program should be visually appealing and interactive.

“As far as like the interactive part, maybe when you feel like you’re making progress, you get some kind of feedback on how the progress is being made.”

DISCUSSION

The results of this study provide preliminary support that a digital intervention may be an acceptable way to address salient topics related to substance use for young adult women in inpatient and residential psychiatric treatment. Although few participants were currently using mental health apps on their own, the majority of women expressed an interest in using a technology-based program as part of their mental health treatment.

Participants endorsed multiple co-occurring mental health problems, including those most common among women with SUDs – depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and trauma (Conway et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2013). Of note, problems with depression and anxiety were reported by all of the women in this sample. Examination of the qualitative data revealed that many women felt that their substance use was connected to their mental health issues, but their current treatment was not adequately addressing their substance use problems. These experiences are, unfortunately, not uncommon. Although integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders has been shown to be superior to separate treatments for each disorder, few mental health treatment facilities are able to provide integrated care (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2020). Participants discussed ways in which technology could be used to help further understand the connections between their substance use and other mental health problems, and as a tool to practice coping skills to help with mental health symptoms and urges and cravings to use substances.

In addition to wanting a more integrated treatment experience, participants expressed the need for treatment to address factors related to their age and stage of life. A few women described difficulties recognizing that they had a substance use problem because substance use, particularly alcohol, was so normalized in their age group. In addition, many women were concerned that they would lose connections with peers if they stopped using substances. Digital interventions that provide personalized normative feedback have been shown to be efficacious in reducing alcohol use in young adult populations, particularly in college student samples (Cronce, Bittinger, Liu, & Kilmer, 2014). Individuals with co-occurring psychiatric disorders may feel particularly isolated from peers. When considering how technology could be used to enhance treatment, it is not surprising that participants expressed interest in having a peer support component.

A gender-responsive approach may be particularly important to women in this age group. Several topics came up related to gender differences in substance use and mental health symptoms, as well as issues salient to women including, sexual abuse, stigma of women with SUDs, the effect of hormones on mood and substance use, and feelings of guilt and shame. Gender-responsive treatment approaches that address the significant sex differences in the epidemiology, physiology, and treatment course of SUDs (Brady, Back, & Greenfield, 2009; Greenfield, Back, Lawson, & Brady, 2010; Greenfield et al., 2011; Greenfield & O’Leary, 2002) have been shown to lead to enhanced treatment outcomes for women with SUDs (Claus et al., 2007; Kissin, Tang, Campbell, Claus, & Orwin, 2014). Previous research has demonstrated feasibility and satisfaction with a web-based gender-specific intervention for women with SUDs (Sugarman, Meyer, Reilly, & Greenfield, 2020). Tailoring this type of intervention for the needs of young adult women with co-occurring disorders may be an effective approach to addressing some of the gaps in treatment.

In addition to the benefits of technology, a few participants described concerns with technology, noting increases in anxiety, isolation, and feelings of being disconnected from reality when using technology. Moreover, the majority of participants rated social media in particular as having a negative effect on their mental health. However, despite these concerns, these women also described benefits of technology as part of treatment, emphasizing the importance of having the technology map on to specific treatment activities. One of the factors that has limited the potential of digital mental health interventions in young adults has been low rates of engagement (Liverpool et al., 2020). Recommendations for increasing engagement include designing interventions that are easy to use and visually pleasing (Liverpool et al., 2020), but it may also be important to consider practical application and relevance to treatment goals for implementation in psychiatric settings. A user-centered design process which emphasizes the importance of understanding the preferences and limitations of end-users is critical in order to maximize the value, uptake, and impact of digital mental health technologies (De Vito Dabbs et al., 2009).

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size is small and the majority of participants were White and non-Hispanic or Latino. However, the clinical characteristics of the study participants are consistent of treatment-seeking women with SUDs with regard to psychiatric comorbidity. Moreover, we saw a saturation of themes in the data, which gives us confidence that the information gathered from the interviews was representative of the sample. Second, we did not formally assess substance use severity. Participants were eligible for the study if they had an identified problem with substance use. By nature, participation in a study for ‘women with mental health and co-occurring substance use problems’ likely reveals that women who enrolled in the study recognized that their substance use was problematic; therefore, these results may not generalize to women who have problematic substance use but are in the pre-contemplative stage. This study also focused on a sample of women receiving care in a psychiatric treatment setting. It would also be important to understand how technology can address the needs of young women with co-occurring disorder in the community who are not willing or able to access treatment.

Despite these limitations, these data identified gaps in current inpatient and residential treatment for young adult women with substance use and co-occurring disorders, as well as important topics for treatment related to gender, age, and stage of life. Moreover, there was high acceptability for using a web-based app as part of mental health treatment, and participants described technology solutions that would enhance their current treatment. These data can be used to inform the development of digital interventions for young women in treatment for substance use and co-occurring disorders. Taken together, these results suggest that a gender-specific digital intervention geared toward young adult women may be a feasible way to address co-occurring substance use in inpatient and residential psychiatric settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participants in this study who shared their stories with us. Portions of this manuscript were presented in poster format at the 52nd annual convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, November 15-18, 2018, Washington, DC.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hall Mercer Endowed Chair in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at McLean Hospital and the National Institute on Drug Abuse K23DA050780 (DES).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest

SLR has received royalty payments from Springer Publishing, Oxford University Press and the American Psychiatric Association Press. SLR has also received payments from the VA for service on a Research Advisory Committee; from Society for Biological Psychiatry for his service as Secretary; and from UT Health as an honorarium for grand rounds. SFG receives small annual royalties from Guilford Press for two books on which she is author and/or co-editor. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ait-Daoud N, Blevins D, Khanna S, Sharma S, Holstege CP, & Amin P (2019). Women and Addiction: An Update. Medical Clinics of North America, 103(4), 699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard C, Silverman AL, Forgeard M, Wilmer MT, Torous J, & Bjorgvinsson T (2019). Smartphone, Social Media, and Mental Health App Use in an Acute Transdiagnostic Psychiatric Sample. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 7(6), e13364. doi: 10.2196/13364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu SM, & Olfson M (2008). Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: Results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(12), 1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, & Greenfield SF (2009). Women & Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukstein OG (2017). Challenges and Gaps in Understanding Substance Use Problems in Transitional Age Youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26(2), 253–269. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, & Carey MP (2009). Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 104(11), 1807–1819. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Binge drinking: A serious, under-recognized problem among women and girls. CDC Vital Signs. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/VitalSigns/BingeDrinkingFemale/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Claus RE, Orwin RG, Kissin W, Krupski A, Campbell K, & Stark K (2007). Does gender-specific substance abuse treatment for women promote continuity of care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(1), 27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM 3rd, Cottler LB, Ben Abdallah A, Phelps DL, Spitznagel EL, & Horton JC (2000). Substance dependence and other psychiatric disorders among drug dependent subjects: race and gender correlates. American Journal on Addictions, 9(2), 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2006). Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(2), 247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Bittinger JN, Liu J, & Kilmer JR (2014). Electronic Feedback in College Student Drinking Prevention and Intervention. Alcohol Res, 36(1), 47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vito Dabbs A, Myers BA, Mc Curry KR, Dunbar-Jacob J, Hawkins RP, Begey A, & Dew MA (2009). User-centered design and interactive health technologies for patients. Comput Inform Nurs, 27(3), 175–183. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e31819f7c7c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deady M, Mills KL, Teesson M, & Kay-Lambkin F (2016). An Online Intervention for Co-Occurring Depression and Problematic Alcohol Use in Young People: Primary Outcomes From a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res, 18(3), e71. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JS, Plaven BE, Yellowlees P, & Shore JH (2020). Remote Telepsychiatry Workforce: A Solution to Psychiatry’s Workforce Issues. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 22(2), 8. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-1128-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, & Brady KT (2010). Substance abuse in women. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(2), 339–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, & Brady KT (2011). Women and addiction. In Lowinson JH & Ruiz P (Eds.), Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, & O’Leary G (2002). Sex differences in substance use disorders. In Lewis-Hall F, Williams T, Panetta J, & Herrerra J (Eds.), Psychiatric Illness in Women: Emerging Treatments and Research. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grist R, Croker A, Denne M, & Stallard P (2019). Technology delivered interventions for depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(2), 147–171. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0271-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Farrer L, Chan JK, Tait RJ, Bennett K, Calear AL, & Griffiths KM (2015). Technology-based interventions for tobacco and other drug use in university and college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Sci Clin Pract, 10(1), 5. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0027-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond AS, Antoine DG, Stitzer ML, & Strain EC (2020). A Randomized and Controlled Acceptability Trial of an Internet-based Therapy among Inpatients with Co-occurring Substance Use and Other Psychiatric Disorders. J Dual Diagn, 16(4), 447–454. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2020.1794094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Compton WM, Eisenberg D, Milazzo-Sayre L, McKeon R, & Hughes A (2016). Prevalence and Mental Health Treatment of Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Among College Students Aged 18–25 Years and Their Non-College-Attending Peers in the United States. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(6), 815–824. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, Whittington C, Stockton S, Glazebrook C, & Davies EB (2017). Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems - a systematic and meta-review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 58(4), 474–503. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes NA, van Agteren JE, & Dorstyn DS (2019). A systematic review of technology-assisted interventions for co-morbid depression and substance use. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 25(3), 131–141. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, Wang S, Pérez-Fuentes G, Kerridge BT, & Blanco C (2013). Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 130(1–3), 101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury L, Tang YL, Bradley B, Cubells JF, & Ressler KJ (2010). Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an urban civilian population. Depression and Anxiety, 27(12), 1077–1086. doi: 10.1002/da.20751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin WB, Tang Z, Campbell KM, Claus RE, & Orwin RG (2014). Gender-sensitive substance abuse treatment and arrest outcomes for women. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(3), 332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattie EG, Adkins EC, Winquist N, Stiles-Shields C, Wafford QE, & Graham AK (2019). Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression, Anxiety, and Enhancement of Psychological Well-Being Among College Students: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res, 21(7), e12869. doi: 10.2196/12869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Perez E, Nogueira C, & DeMartini KS (2015). Very-Brief, Web-Based Interventions for Reducing Alcohol Use and Related Problems among College Students: A Review. Front Psychiatry, 6, 129. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein DP, Spirito A, & Zimmermann RP (2010). Assessing and treating co-occurring disorders in adolescents: Examining typical practice of community-based mental health and substance use treatment providers. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(3), 252–257. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9239-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverpool S, Mota CP, Sales CMD, Čuš A, Carletto S, Hancheva C, … Edbrooke-Childs J (2020). Engaging Children and Young People in Digital Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review of Modes of Delivery, Facilitators, and Barriers. J Med Internet Res, 22(6), e16317. doi: 10.2196/16317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, & Borodovsky JT (2016). Technology-based Interventions for Preventing and Treating Substance Use Among Youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(4), 755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Sugarman DE, & Greenfield SF (2018). Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2020). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: Volume I, Secondary school students. Retrieved from Ann Arbor: http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). Common Comorbidities with Substance Use Disorders. Research Report. Retrieved from [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Ellis JD, Resko SM, & Grekin E (2019). Technology-Delivered Interventions for Substance Use Among Adolescents. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 66(6), 1203–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwa H, Guerrero EG, Braslow JT, & Fenwick KM (2015). Barriers to serving clients with co-occurring disorders in a transformed mental health system. Psychiatric Services, 66(5), 547–550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, & McGorry P (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60368-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2019). Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2019. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/06/13/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2019/

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2015). NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 11 (Version 11).

- Riecher-Rössler A (2017). Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry, 4(1), 8–9. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30348-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, & Patrick ME (2019). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–60. Retrieved from http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs

- Sonne SC, Back SE, Diaz Zuniga C, Randall CL, & Brady KT (2003). Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal on Addictions, 12(5), 412–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steingrimsson S, Carlsen HK, Sigfusson S, & Magnusson A (2012). The changing gender gap in substance use disorder: A total population-based study of psychiatric in-patients. Addiction, 107(11), 1957–1962. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55) Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, Campbell ANC, Iles BR, & Greenfield SF (2017). Technology-based interventions for substance use and comorbid disorders: An examination of the emerging literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25(3), 123–134. doi: 10.1097/hrp.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, Meyer LE, Reilly ME, & Greenfield SF (2020). Feasibility and Acceptability of a Web-Based, Gender-Specific Intervention for Women with Substance Use Disorders. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 29(5), 636–646. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, & Rosenbaum JF (2013). Transitional aged youth: A new frontier in child and adolescent psychiatry. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(9), 887–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule AM, & Kelly JF (2019). Integrating Treatment for Co-Occurring Mental Health Conditions. Alcohol Res, 40(1). doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.1.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.