Abstract

In addition to numerous care responsibilities, family caregivers are expected to navigate health systems and engage in healthcare management tasks on behalf of their persons living with dementia (PLWD). These challenging tasks pose additional difficulties for Black dementia caregivers. Due to the centuries-old, disadvantaged social history of Black Americans, several unique stressors, vulnerabilities, and resources have emerged which inform and affect Black dementia caregivers’ experiences and well-being. Focus groups were held with Black caregivers (N = 19) from the United States to explore the unique experiences and perspectives of this population navigating the U.S. health system on behalf of their PLWD. Five overarching themes were constructed during thematic analysis: Forced Advocacy, Poor Provider Interaction, Payor Source Dictates Care, Discrimination, and Broken Health System. Black dementia caregivers unanimously concurred that the health system that they experience in America is “broken.” Gaps in the health system can lead to people [as one caregiver passionately expressed] “falling between the cracks,” in terms of care, services, and resources needed. Caregivers agreed that class, sex, utilizing public health insurance, and being a “person of color” contribute to their difficulties navigating the health system. Caregivers perceived being dismissed by providers, forcing them to advocate for both themselves and their PLWD. Healthcare providers and researchers can utilize these findings to improve the experiences and healthcare outcomes of Black persons living with dementia and their caregivers. Additionally, these findings can lead to the development of culturally tailored caregiver education programs.

Keywords: African American, Alzheimer’s disease, care partners, healthcare navigation, insurance

INTRODUCTION

In addition to numerous responsibilities caregivers take on, they are also expected to engage in healthcare navigation and management tasks on behalf of their persons living with dementia (PLWD).1,2 These tasks primarily include identifying and coordinating healthcare services and support such as preventative community-based groups, scheduling follow-up appointments, navigating emergency care, exchanging information with providers, and participating in health decision-making processes.1 These challenging tasks pose additional difficulties for Black dementia caregivers experiencing a lack of service knowledge, limited communication with healthcare providers, and difficulty navigating the U.S. health system on behalf of whom they provide care.3,4 Black families faced with dementia (Medicare beneficiaries) incur 1.7 times more in healthcare costs and higher proportions of preventable hospitalization than White families.5

Difficulties navigating healthcare have been linked to Black caregivers’ having fewer financial resources with which to provide care versus their White counterparts.3 Black caregivers and their PLWDs that experience disparities in care are generally under-treated and have lower rates of formal service use.6 Although participation in public health insurance programs, such as Medicaid, can significantly reduce burden and stress often associated with dementia caregiving, Black caregivers do not typically consider formal healthcare resources a priority support option.7,8 Instead, many lean on family-system resources, leading to a trend toward underutilization of available services and resources.8,9

Complexities of Black caregiving are seen through the lens of racism and associated health disparities.8 Health and socioeconomic disparities, as well as systemic racism, are factors that not only contribute to an increase in Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia risk in Black Americans and other underrepresented communities, but also serve as barriers to optimal healthcare access and navigation for caregivers.10–12 To aid this population of family caregivers, we must understand the extent of challenges and complexities they encounter when navigating the healthcare system. This study sought to understand Black dementia caregivers’ perspectives and attitudes toward the U.S. health system and explore their experiences of navigating this system with their PLWD.

METHODS

To explore the emic perspectives of Black caregivers of PLWD, the phenomenon of navigating the U.S. health system was investigated through a descriptive qualitative study using focus groups. This study was carried out with low levels of interpretation from the researchers to accurately analyze the experiences of caregivers in this unique situation.13 Institutional Review Board approval was granted for this study (BLINDED #00002078).

Recruitment

Purposeful sampling, using convenience, and snowball techniques were used to recruit a sample of caregivers with rich lived experiences.14 Advertisements were shared with an external advisory board of Black dementia research and healthcare experts and community partners (i.e., nonprofit organizations serving Black communities) to distribute within their networks. Caregivers nationwide were eligible if they identified as Black American adults and were responsible for most health system interactions within this past year for their PLWD.

Data collection

Nineteen dementia caregivers consented to this study; they were given the option to participate in a focus group on either of two dates. A team member (Stephanie G. Bennett) facilitated two semistructured focus group sessions in April of 2021; see Table 1 for the interview guide. Each focus group (n = 9, n = 10) lasted approximately 1.5 h and was audio recorded through a videoconferencing platform. Caregivers received a $40 electronic gift card at the conclusion of the sessions. During transcription, caregiver names and locations, such as medical facilities and cities of origin, were de-identified using pseudonyms and identification numbers. Quality and trustworthiness were assured by using a standardized methodology for qualitative research.15 To address credibility and confirmability, researchers provided a brief bullet-point list of the group’s main observations, and the group was asked to clarify or add points before the conclusion of the focus group.

TABLE 1.

Focus group interview guide

| Questions |

|---|

| 1. What are your views on the health care system here in America? |

| 2. On a scale 1–5, How confident (competent) do you feel in navigating the health system? (Scheduling appointments, health-related tasks, managing insurance, accessing health-related resources, etc.)? |

| 3. What has it been like to navigate the health system for you, for your person with dementia (scheduling appointments, health-related tasks, managing insurance, accessing health-related resources etc.)? |

| 4. How has COVID-19 affected your interaction with the health care system? |

Research team members’ participation in focus groups minimized the risk of bias. In reference to authenticity, caregivers were from four states (GA, NC, IL, CA), represented various age ranges, and cared for individuals over a broad range of stages and types of dementia.

Data analysis

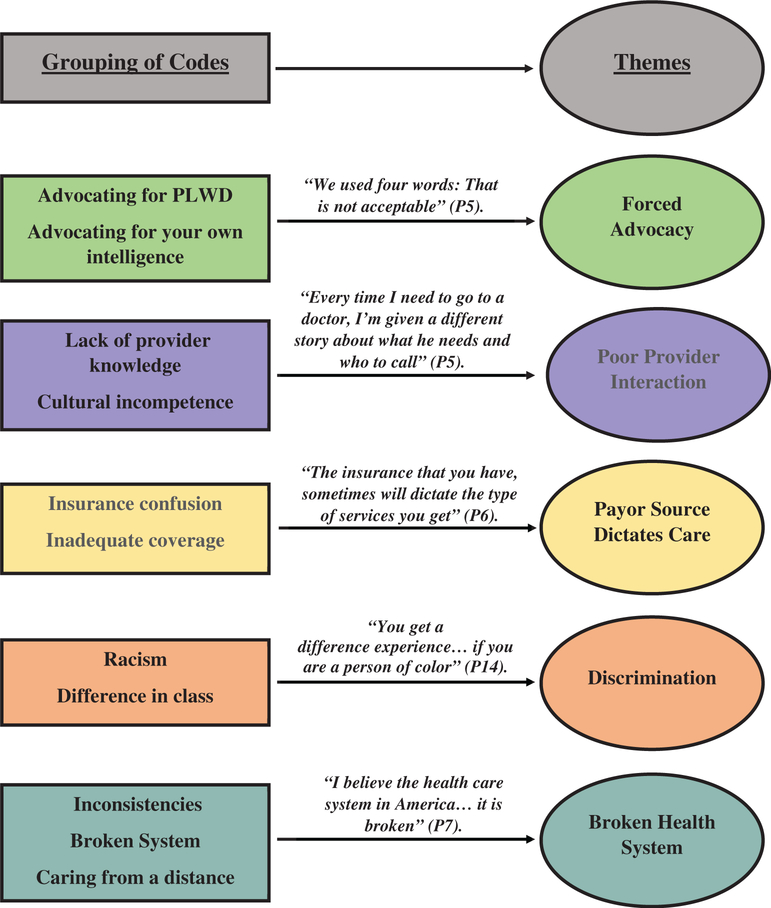

After transcription and de-identification, a secure cloud network, available for all involved in the study, was used to store transcripts. Researchers (Karah Alexander, Sloan Oliver, and Fayron Epps) thematically analyzed the two focus group transcripts using the six phases described by Braun and Clarke.16 In phase 1, team members familiarized themselves with the data by repeated reading of transcripts. Phase 2 consisted of manually generating 14 initial codes, in which team members organized quotes from the transcripts into categories created by the emerging codes. In phases 3 and 4, searching for themes and reviewing themes, five overarching themes were developed and refined from the initial codes. In phase 5, the themes were named and defined. Figure 1 illustrates the grouping of codes and constructed themes. To complete the thematic analysis, phase 6, producing the report, was done to tell the story of Black American caregivers struggling to navigate their health systems.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of themes

RESULTS

Nineteen Black dementia caregivers participated in one of two focus groups. The mean age of the caregivers was 60 years (SD = 9.5), and majority were female (89.5%, n = 17). The average number of years spent caregiving for a PLWD was 7.7 years (SD = 6.5). All caregivers had some form of college education and approximately half of the sample had a graduate degree (53%, n = 10). See Table 2 for caregiver demographic data.

TABLE 2.

Caregiver demographics (N = 19)

| Participant ID | Age | Gender identity | Education | Relationship to PLWD | Caregiving length (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 61 | Female | Graduate degree | Spouse | 5 |

| P2 | 59 | Female | College graduate | Child | 20 |

| P3 | 66 | Female | College graduate | Friend | 1 |

| P4 | 54 | Male | Some college | Spouse | 4 |

| P5 | 47 | Female | Come college | Friend | 2 |

| P6 | 73 | Female | College graduate | Spouse | 3 |

| P7 | 54 | Female | Some college | Spouse | 5 |

| P8 | 75 | Female | Graduate degree | Spouse, child | 8 |

| P9 | 60 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 11 |

| P10 | 53 | Male | College graduate | Nephew | 1 |

| P11 | 75 | Female | Graduate degree | Spouse | 17 |

| P12 | 62 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 8 |

| P13 | 46 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 8 |

| P14 | 51 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 1 |

| P15 | 72 | Female | Some college | Spouse | 8 |

| P16 | 46 | Female | Some college | Child | 6 |

| P17 | 54 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 11 |

| P18 | 66 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 25 |

| P19 | 68 | Female | Graduate degree | Child | 3 |

Themes

Five overarching themes emerged from transcript analysis: (1) Forced Advocacy, (2) Poor Provider Interaction, (3) Payor Source Dictates Care, (4) Discrimination, and (5) A Broken Health System.

Forced advocacy

According to some caregivers, PLWD without advocates can struggle to receive the correct treatment “they need in order to maintain a healthy style of living” (P3). One caregiver shared how she is an advocate for her father and feels sorry for “seniors who do not have someone who is questioning the care they’re given, whaťs recommended” (P2). Additionally, caregivers discussed how they were forced to advocate for themselves as well as their PLWD. One caregiver stated:

“Not only do I have to deal with racial issues, I also have to deal with making sure my loved ones are represented in a medical way that is outstanding as it correlates with my peers” (P1).

During visits with providers, it was sometimes common for caregivers’ concerns to be overlooked, forcing them to have to advocate for better quality care for their PLWD. For example, caregivers stated they “had to pull the doctor aside” (P4) and “had to insist” (P5) that the doctor be more attentive and provide appropriate care for their PLWD. Another caregiver had to pry information from the doctor because it seemed that was the only way she could receive details: “… I’m also finding when we go to the doctor … I have to really advocate and have to ask questions” (P6). The caregivers also faced issues when discussing treatment for whom they provide care, “… because they see you, they assume you don’t know any better” (P7).

Poor Provider interaction

Caregivers discussed their poor interactions with healthcare providers when trying to get help for their PLWD. Such interactions contributed to one caregiver’s feelings that her father was not “getting the best care he should be getting at this stage …” (P12). When it came to discussing health concerns that may not be attributed to their person’s dementia illness, another caregiver felt that “sometimes the doctors wanna- or just relate it [external symptoms and health issues] all to, ah, dementia or Alzheimer’s. And I- and I don’t feel that way a lot of times …” (P6). Other caregivers shared similar experiences, often feeling “dismissed” (P15) by providers. A caregiver also shared her and her mother’s interactions with insensitive providers:

“So, one of her doctors told her that, after the diagnosis of breast cancer … you shouldnť really worry about it anyway, because you won’t even know you have breast- because you have dementia … I thought that was very harsh” (P16).

Challenges often arose when caregivers sought assistance from healthcare administrative staff such as accessing health records for their PLWD and seeking information from multiple healthcare professionals. One caregiver expressed her frustrations of getting the run around from administrators and being given a “different story” (P15) from different physicians regarding what her husband needed, answers to her questions, and overall information. Overall, caregivers who spoke about the negative experiences with healthcare providers agreed these poor interactions were serving as barriers to optimal care for their PLWD.

Payor source dictates care

Numerous caregivers felt the source of payment for healthcare costs dictated the kind and level of care provided to their PLWD. Confusion existed among caregivers about the difference types of insurance coverage. Distraught over the difference between private and public health coverage, one caregiver asked:

“… I guess iťs … Medicare’s a private insurance? Is Medicare private insurance? Am I right? Like, Blue Cross Blue Shield, she has United Healthcare. So thaťs Medicare, right? Would that be Medicare, or the government is Medicaid? I get confused. Does anybody know, can (anyone?) answer my question?” (P17).

Another caregiver, regardless of how long she provided care to her person living with dementia, still wondered how the public health insurance programs— Medicaid and Medicare, differed from each other, stating she has never known how either plan “worked” (P10). The type of insurance coverage was also met with stigma by some participants, who felt private insurance dictated better care and “service” for their PLWD. One caregiver further elaborated:

“… you have a Blue Cross Blue Shield, they’re gonna treat you great. If you have a Medicare or a Medicaid, it is so hard to get anything, um, done, accomplished, anything whatsoever …” (P14).

Inadequate insurance coverage was a common concern among the caregivers, and what many felt contributed to the U.S. health system being broken. Caregivers questioned what was deemed covered and not covered by private or public health insurance, especially when living as a “hard working citizen” or even a “veteran” (P11) for decades in this country.

Discrimination

Caregivers highlighted how race, nationality, social class, and gender played a significant role in the care they received. The U.S. health system was described as “a system of racism” by a caregiver (P11). Another caregiver stated, “of course disparities exist and they’re pretty paramount and quite obvious in many cases” (P1); a sentiment echoed by several of the other caregivers. One caregiver noted:

“You get a different experience—even if you are a person of color … Iťs very racial. Iťs very sexist … iťs just horrible all the way around, if you’re a Black person or a woman” (P14).

One caregiver went into further detail, highlighting that race, as well as ethnicity, played a part in her husband’s suboptimal care. Classism and sexism were also experienced by some of the caregivers, with some feeling they were categorized as “lower class,” and thus, were not provided optimal treatment and attention from providers.

During the focus group sessions, caregivers were reluctant at first to talk about racism and how it may have affected the care they received. Some caregivers did not want attribute their experiences to racism even though they encountered interactions that seemed to be grounded in a form of discrimination. When discussing their experiences navigating the health system for their PLWD, caregivers specified how it is not just race and sex, but “that a lot of times the subtle piece that exists in America of social class comes into play … iťs more been a class thing” (P9). Overall, caregivers expressed discrimination leads to inequities and health disparities impacting them and their PLWD.

A broken health system

Gaps in the health systems lead to people “falling between the cracks” (P8) and prevents access to the care, services, and resources one needs; one caregiver stated, “some places are just cracks; others are craters in the system itself” (P7). Variation in care and how such “inconsistencies make it difficult to get comprehensive care” (P9) were widely described by caregivers. The U.S. health system was most commonly described as being broken with caregivers stating, “for me, I believe the healthcare system in America, as a whole … is broken” (P7); “as far as the system being broken … I can attest to that” (P10); and “I think the healthcare system is broken … I just don’t think we have … a healthcare system in general that really looks at the patient as a whole person …” (P9).

Many caregivers navigating veterans-specific health systems when caring for their PLWD stated these facilities gave caregivers additional challenges, such as having “different standard[s] in terms of getting … good care” (P11) and caregivers’ perceived notions that this system did “not want to spend … the money they should to give adequate care to the veterans” (P12). One caregiver stated:

“Sometimes things are dismissed based on age. I feel like a lot of times with the older veterans, they’re kind of dismissive of some things or wanna take a wait and see approach, because they maybe don’t wanna invest the time, the money” (P13).

Along with navigating local health systems, many caregivers mentioned “having to cut through their red tape” (P10) when navigating the health system from a distance, whether it be commuting from rural to urban areas or state to state to care for their PLWD. Caregivers emphasized, “I would say the healthcare system, it sucks if you are … a person of color” (P14).

DISCUSSION

For a caregiver of a PLWD, visiting a healthcare facility is not uncommon, neither is overcoming the hurdles that come with navigating system intricacies. Caregivers experience health systems differently than the rest of the population and therefore face different challenges. Black caregivers, in particular, face an array of unique challenges when navigating healthcare on behalf of those for whom they provide care for, as seen in the analysis of these focus groups. Caregivers felt older adults living with dementia experience a disadvantage when they do not have anyone advocating on their behalf. Additionally, caregivers expressed experiences of falling into cracks, living in craters, and trying to navigate a broken system to access the services needed to improve outcomes for their PLWD. Discrimination, communication challenges, and misunderstanding of insurance types and respective coverage were a few of the many factors that Black caregivers felt strongly about regarding the U.S. health system and what they felt affects their ability to efficiently navigate healthcare on behalf of their PLWD.

In acknowledging the COVID-19 pandemic and how it may have further impact on caregivers’ ability to navigate healthcare on behalf of their PLWD, caregivers were also asked how their interactions with the health system may have been affected during the pandemic. Although a few caregivers had specific individual difficulties related to the pandemic, most were still in agreement that despite the pandemic, navigating the health system was equally challenging prior to the pandemic.

Systemic discrimination in the U.S. health system concerning race, sex, payor source, and social class was experienced by Black caregivers of PLWD in this study. Many felt navigating the complicated health system is even more complex for persons of color, or of a different nationality, due to discriminatory attitudes perpetuated by healthcare providers and administrators. The compilation of the instances of discrimination expressed in this study points to a systemic problem-facing caregivers who are made to navigate the health system when experiencing discrimination based on differences in identities, race, sex, and class. These findings echo those from other studies. According to an Alzheimer’s Association survey of U.S. adults, more than one-third of Black Americans believed discrimination would serve as a barrier to receiving Alzheimer’s Disease care, and half reported having experienced racial discrimination in healthcare overall, compared with fewer than 1 in 10 White Americans.17 Additionally, 41% of caregivers who provide informal care to a Black Americans, reported race makes it more difficult for them to get excellent healthcare.17 According to research, systemic racism has led to the development and perpetuation of implicit biases (individual/organization), stereotypes, microaggressions, and prejudices that are prominent in healthcare today.18

Research suggests nurses and physicians are valued sources of accurate information and can interpret confusing clinical information for caregivers of PLWD; however, poor communication practices can render these conversations ineffective.4 A few caregivers described their interactions with providers them as poor and disconnected; they detailed how physicians dismissed their primary concerns, equating reports of external symptoms and health issues with dementia illness. Additionally, caregivers spoke about the poor chain of communication they experience when having to coordinate with their PLWD’s multiple providers. These experiences were described as getting the “run around”; one provider will refer to another, and so forth. Thus, caregivers were not given actionable, straightforward responses to specific questions regarding treatment regimens, follow-up plans, and other health concerns.

The finding that caregivers described their interactions with providers as culturally insensitive is also consistent with the literature. Individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups want providers to understand their unique backgrounds and experiences; however, many doubt they would be able to access culturally competent providers.19 Although many healthcare providers deny racial bias, they also do not acknowledge unconsciously embracing stereotypes that influence the way they deliver care to Black families.20 Trust is widely acknowledged to be essential for effective communication and compliance with healthcare.19,21 Lack of cultural sensitivity and cultural competence on the part of the physician and other healthcare workers can breed mistrust of medicine and healthcare by racial and ethnic minority communities, mistrust affects their healthcare choices.21,22

Misunderstanding and misperceptions about health insurance coverage also affect Black American healthcare choices.7,23 Black Americans report numerous challenges when choosing an insurance plan most appropriate for their circumstances and find it challenging to understand and use their coverage.23 Studies have found a sizable number of Black Americans view the insurance selection process as complex and very political, some noting that these views prevent them from seeking needed medical treatment.24 Much confusion persisted among Black dementia caregivers in this study when it came to knowing the difference between public health and private insurance coverage and the details of their respective insurance plans. Aside from confusion, stigma was also present. Many caregivers believed private insurance was “good” and public insurance equivalated to “bad,” thereby warranting poorer treatment from providers. Black caregivers are well-positioned to benefit from services and resources covered by different insurance plans such as Medicaid Assistance Programs, including Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS)-Waiver Programs such as adult day care, in-home, and respite care.7 Black American PLWD are underserved, living without the financial assistance and support services HCBS programs can provide.25 This is primarily due to misconceptions of not meeting required financial criteria, the application is too difficult and time-consuming to complete, and the false notion of losing their assets and homes upon receiving assistance.25 Subsequently, caregivers are at risk of jeopardizing their ability to continue to provide quality care due to increased financial strain, emotional and physical stress, and eventually, “burnout.”25,26

Limitations

Limitations existed in this study. Caregivers were recruited from a small convenience sample, many of whom had connections to the primary investigator (Fayron Epps), which may have resulted in selection bias. Secondly, the sample was comprised of highly educated caregivers, the majority of whom either had some college or a graduate degree, which may limit generalizability.

Future research and implications

Geriatrics education training programs and continuing education have been successful in changing attitudes and perceptions related to older care27; therefore, such programs should also incorporate topics related to the impact of systemic discrimination. Healthcare providers, educators, and researchers can utilize findings from this study to understand the complexities Black American dementia caregivers face when navigating healthcare on behalf of their PLWD and improve Black dementia patient and family experiences in the healthcare setting. Acknowledging and understanding how various racial and ethnic groups, as well as external marginalized populations who have had historically worse quality of care, experience the health system in America is crucial to improving the system and aiding providers in caring for an increasingly diverse population of minority older adults.28 It is recommended for further research to examine the experiences of navigating U.S. health systems faced by other marginalized groups (e.g., economically disadvantaged, Latinx, and LGBTQIA+) of caregivers’ as they too may experience unique complexities.

The findings from this study can serve as the context and foundation for development of culturally tailored caregiver education programs and interventions. For example, we have developed a culturally tailored online education course that addresses the cultural reality of caregiving for persons living with dementia as a Black American. To develop this course, we revised an existing online caregiving course to address pertinent cultural differences in the caregiving experience of Black Americans based on the findings of this study. For the course materials to be well received, we recorded and strategically partnered with Black healthcare professionals, caregivers, and persons living with dementia to address key concerns and challenges faced when caregiving and navigating healthcare for an individual living with dementia. It is our hope for Black caregivers who complete this course will feel empowered to interact with the health system, competently care for their person, and better engage in self-care activities.

Key points.

Navigating the U.S. health system on behalf of a person living with dementia poses unique challenges and stressors for Black caregivers.

Black dementia caregivers view the U.S. health system as broken with many “cracks.”

Black dementia caregivers that express class, sex, utilizing public health insurance, and being a “person of color” are determinants that contribute to their difficulties navigating the U.S. health system.

Why does this paper matter?

To improve health outcomes and promote health equity in dementia among racial and ethnic minority groups, we need to understand the experiences of racial and ethnic minority patients and families when interacting with the health system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors extend their gratitude to the caregivers for their time and participation.

Funding information

This work is supported by the Retirement Research Foundation for Aging [2020213 (Fayron Epps)]. The authors would like to acknowledge this work also resulted from the development plan and activities of Dr Epps’ career development award through the National Institute on Aging, a division of the National Institutes of Health [K23AG065452 (Fayron Epps)]. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement of The Retirement Research Founding for Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose that are relevant to this study.

SPONSOR’S ROLE

Sponsors had no role in the design, methods, caregiver recruitment, data collection, analysis, or construction of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fields B, Rodakowski J, James E, Beach S. Caregiver health literacy predicting healthcare communication and system navigation difficulty. APA. 2018;36(4):482–492. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia C, Espinoza S, Lichtenstein M, Hazuda H. Health literacy associations between Hispanic elderly patients and their caregivers. J Health Commun. 2013;18(1):256–272. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.829135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramsohn ME, Jerome J, Paradise K, Lostas T, Spacht AW, Lindau TS. Community resource referral needs among African American dementia caregivers in an urban community: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullins J, Bliss ZD, Rolnick S, Henre AC, Jackson J. Barriers to communication with a healthcare provider and health literacy about incontinence among informal caregivers of individuals with dementia. J WOCN. 2016;43(5):539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unpublished tabulations based on data from the National 5% Sample Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries for 2014. Prepared under contract by Avalere Health to the Alzheimer’s Association, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dilworth-Anderson P, Pierre G, Hilliard TS. Social justice, health disparities, and culture in the care of the elderly. JLME. 2012;40(1):26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coogle CL. Caregiver education and service utilization in African American families dealing with dementia. African Am Res Persp. 2004;10:140–151. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crewe SE, Chipungu SS. Services to support caregivers of older adults. In: Berkman B, ed. Handbook on Social Work in Health and Aging. Oxford University; 2006:539–550. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. Caregiving in the U. S http://www.caregiving.org/data/04finalreport.pdf. Accessed July, 25, 2021

- 10.Fabius CD, Wolff JL, Kasper JD. Race differences in characteristics and experiences of black and white caregivers of older Americans. Gerontologist. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weuve J, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Cognitive aging in Black and White Americans: cognition, cognitive decline, and incidence of Alzheimer disease dementia. Epidemiology. 2018;29(1):151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colorafi K, Evans B, Anef F. Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD. 2016;9(4):16–25. doi: 10.1177/1937586715614171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gareth J, Riggs T, Riggs D. Ensuring quality in qualitative research. Qual Res Clin Health Psychol. 2015;57–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-137-29105-9_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton M Qualitative evaluation and research. Methods. 1990; 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virginia B, Victoria C. Using thematic analysis in psychology. J Qual Res. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alzheimer’s Association (Online) Special Report. Race, ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s in America. Accessed July 29, 2021 https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-special-report.pdf.

- 18.Systemic Racism and the Ignored Health Disparities Among African-Americans in the US. Healthcare and Medical News for Atlanta Physicians 2021. (Online). Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.mdatl.com/2021/03/systemic-racism-and-ignored-health/.

- 19.Kennedy B, Mathis C, Woods A. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Diver. 2007;14(2):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watkins J, Bonner J, Wang E, Wilkie J, Ferrans E, Dancy B. Relationship among trust in physicians, demographics, and end-of-life treatment decisions made by African America dementia caregivers. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2012;14(3):238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen R, Hodgson A, Gitlin NL. Iťs a matter of trust: older African Americans speak about their health care encounters. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;35(10):1058–1076. doi: 10.1177/0733464815570662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali N, Combs M, Muvuka B, Ayangeakaa D. Addressing health insurance literacy gaps in an urban African American population: a qualitative study. J Health Commun. 2018;43: 1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villagra G, Bhumika B, Coman E, Smith O, Fifield J. Health insurance literacy: disparities by race, ethnicity, and language preference. AJMC. 2019;25(3):71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kingsberry Q, Mindler P. Misperceptions of Medicaid ineligibility persist among African American caregivers of Alzheimer’s dementia care recipients. PHM. 2012;15(3):174–180. doi: 10.1089/pop.2011.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabin WD. Moving toward Medicare home health coverage for persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008; 51:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacala TJ, Boult C, Hepburn K. Ten years’ experience conducting the aging game workshop: was it worth it? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vyjeyanthi SP. Building a culturally competent workforce to care for diverse older adults: scope of the problem and potential solutions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S423–S432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]