Abstract

Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) can regulate the progression of numerous types of cancer; however, the bone invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) has been poorly investigated. In the present study, the effect of verrucous SCC-associated stromal cells (VSCC-SCs), SCC-associated stromal cells (SCC-SCs) and human dermal fibroblasts on bone resorption and the activation of HSC-3 osteoclasts in vivo were examined by hematoxylin and eosin, AE1/3 (pan-cytokeratin) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining. In addition, the expression levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)9, membrane-type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP), Snail, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) in the bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells were examined by immunohistochemistry. The results suggested that both SCC-SCs and VSCC-SCs promoted bone resorption, the activation of osteoclasts, and the expression levels of MMP9, MT1-MMP, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP. However, SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect compared with VSCC-SCs. Finally, microarray data were used to predict potential genes underlying the differential effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on bone invasion in OSCC. The results revealed that IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12, INS and NGF may underlie these differential effects. In conclusion, both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs may promote bone invasion in OSCC by enhancing the expression levels of RANKL in cancer and stromal cells mediated by PTHrP; however, SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect. These findings may represent a potential regulatory mechanism underlying the bone invasion of OSCC.

Keywords: oral squamous cell carcinoma, bone invasion, osteoclast, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand, parathyroid hormone-related peptide, microarray, cancer-associated stromal cells

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common type of malignant tumor in the head and neck region. It has a high rate of recurrence and distant metastasis, and can also invade into nearby bone tissues, such as the maxilla and mandible, resulting in bone destruction and difficult treatment of OSCC (1–4). Bone invasion in OSCC is mediated by osteoclasts rather than cancer cells. Osteoclastogenesis is regulated by receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK), RANK ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin, which belong to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family (5–7). Cancer-induced bone destruction is regulated by various factors that are synthesized by cancer cells, including parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), interleukin (IL)-6, IL-11, TNF-α and prostaglandin E2, which are also synthesized by OSCC cells (8–11). These factors stimulate RANKL expression in stromal and osteoblastic cells adjacent to the resorbing bone. IL-6 produced by stromal cells in OSCC can induce fibroblastic stromal cells to produce RANKL (12). Therefore, it is necessary to study the potential mechanisms by which OSCC invades bone tissue.

Solid tumors consist of parenchymal and stromal areas, and the crosstalk between them serves a crucial role in the progression of cancer (13). Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) mainly consist of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages and immune cells, which have a significant role in the invasion and metastasis of cancer (14). The highly expressed C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) in CAFs has been reported to promote the invasion of the poorly-differentiated oral cancer cell line SAS (15). In addition, the Axin2-Snail axis may promote the activation of CAFs in the TME, which in turn can enhance the bone invasion of OSCC (16). Compared with in normal fibroblasts, the overexpression of RANKL in CAFs may activate osteoclasts, resulting in the bone invasion of OSCC. In addition, CAFs can induce macrophage transfer into osteoclasts by co-culture with macrophages (17). Therefore, stromal cells in the TME could regulate the bone invasion of OSCC by crosstalk with cancer cells. However, to the best of our knowledge, the details of how the tumor stroma influences bone resorption in cancer cells remain unknown.

The differences between the macroscopic subtypes of OSCC are defined by cancer parenchyma properties. OSCC is divided into the endophytic (ED)-type and exophytic (EX)-type according to its invasive abilities. ED-type OSCC is invasive and can occasionally metastasize. Conversely, EX-type OSCC, such as verrucous OSCC, presents an outward growth, does not invade the subepithelial connective tissue and does not metastasize (18–20). We previously reported that the cancer stroma regulates the biological characteristics of cancer parenchyma. In addition, EX-type verrucous SCC-associated stromal cells (VSCC-SCs) and ED-type SCC-associated stromal cells (SCC-SCs) were shown to have different effects on bone invasion, migration and differentiation of HSC-2 and HSC-3 cells. Furthermore, the expression levels of α-SMA in SCC-SCs were revealed to be higher than those in VSCC-SCs. Apart from this, the detailed different marker profiles between VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs were analyzed using microarray data (21,22). However, these previous studies only identified the effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on bone invasion of OSCC and did not assess the potential regulatory mechanisms. The present study aimed to investigate the detailed phenomenon and potential regulatory mechanisms by which VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs regulate the bone invasion of OSCC using tumor stroma established from patients with OSCC with different degrees of invasiveness. For this purpose, HSC-3 cells were selected as a cell model due to the fact that HSC-3 is a poorly-differentiated oral cancer cell line with obvious bone invasion ability that is widely used in bone invasion research (12,23). Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were selected as a negative control, mainly because HDFs are normal fibroblasts that are not edited by cancer cells (21,22). VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs were extracted from patients with OSCC to examine their effects. These findings highlight the potential regulatory mechanism underlying bone invasion in OSCC.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

The human oral cancer cell line HSC-3 was purchased from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank. HDFs (cat. no. CC-2511) were purchased from Lonza Group, Ltd. The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 was obtained from the RIKEN BioResource Center. VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs were extracted from surgical operative tissues at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences (Okayama, Japan). The VSCC tissues were obtained from one patient with VSCC and SCC tissues were obtained from one patient with SCC (mean age, 81 years; sex of patients, both female), to separate the stromal cells and generate the cell culture. Sections of fresh OSCC tissue (1 mm3) were washed several times with α-Modified Eagle's medium (α-MEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing antibiotic-antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and then minced. The tissues were then treated with α-MEM containing 1 mg/ml collagenase II (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and dispase (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 2 h at 37°C with agitation (200 rpm). The released cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 111.8 × g at room temperature, suspended in α-MEM containing 10% FBS (Biowest), filtered through a cell strainer (100 µm; Falcon; Corning Life Sciences), plated in a tissue culture flask and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 1 week, the stromal cells were separated by Accutase (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) based on the different adhesive properties of epithelial and stromal cells (21,22). HSC-3, VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs were maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antimycotic-antibiotic at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Okayama University (project identification code: 1703-042-001). In addition, written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining of cells

RAW264.7, HSC-3, VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs were digested with Accutase and EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and centrifuged at 111.8 × g for 5 min at room temperature when the density approached 90%. RAW264.7 cells were mixed with or without VSCC-SCs/SCC-SCs/HDFs and HSC-3 at a 3:3:1 ratio. The mixed cells were seeded into a 6-well plate containing coverslips (22×22 mm; Matsunami) at a density of 3.5×105/well. After incubation for 3 days (37°C), the attached slides were washed three times with TBS and were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After washing with TBS for a further three times, the slides were stained using a TRAP staining kit (cat. no. AK04F; Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions in 37°C incubator. Images of the slides were captured using a bright-field microscope (magnifications, ×4, ×10, ×20 and ×40; BX51; Olympus Corporation). A total of five images (magnification, ×40) were randomly captured to calculate the percentage of positive osteoclast cells (percentage of TRAP-positive cells) using ImageJ software (version 1.53K; National Institutes of Health).

Experimental animals

All animal experiments were conducted according to the relevant guidelines and regulations approved by the institutional committees at Okayama University (approval no. OKU-2017406). The anesthesia protocol was performed in accordance with Laboratory Animal Anesthesia, 3rd edition (24). To confirm mice were appropriately anesthetized, the mice were checked to determine whether they would return to a prone position when they were placed on their backs. Following intraperitoneal anesthesia with ketamine hydrochloride (75 mg/kg body weight) and medetomidine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg body weight), 200 µl mixed cells including HSC-3 (1×106, 100 µl) and stromal cells (VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs; 3×106, 100 µl) were injected into the subcutaneous tissue in the central region of the top of the head of 20 healthy female BALB-c nu-nu mice (age, 4 weeks; mean weight, 15 g; Shimizu Laboratory Supplies Co., Ltd) gradually and slowly (16). All mice were reared in an animal room at a temperature of 25°C with 50–60% humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle. All mice were allowed free access to food and water. The experimental animals were divided into the HSC-3, HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs, HSC-3 + SCC-SCs and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (n=5/group). Of the five mice, one mouse in each group exhibited poor tumor formation; therefore, their data were removed and the data from the remaining four mice were used for data analysis.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

After 4 weeks, all mice were sacrificed by excess inhalation of isoflurane (concentration >5%). Cardiac arrest was verified by pulse palpation followed by cervical dislocation. The whole heads of mice containing the tumor and bone tissues were removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h and decalcified with 10% EDTA for 4 weeks at 4°C. Subsequently, the whole heads of animal models were processed and embedded into paraffin wax through routine histological preparation and further cut into 5-µm sections. Finally, the sections were used for H&E staining. The sections were stained with Carrazi's hematoxylin (Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd.) for 5 min at room temperature and stained with eosin (Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd.) for 7 min at room temperature. Images of the bone invasion regions of tissues were captured using a bright-field microscope (magnification, ×40).

TRAP staining of tissue

The 5-µm sections of tissue samples from the HSC-3, HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs, HSC-3 + SCC-SCs and HSC-3 + HDF groups were used for TRAP staining using the aforementioned TRAP staining kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, and active multi-nucleated osteoclasts on the bone surface were considered to be TRAP-positive cells. The bone invasion regions of tissues were photographed using a bright-field microscope. A total of five images (magnification, ×40; BX51; Olympus Corporation) were randomly captured from each mouse to obtain positive cell counts using ImageJ software (version 1.53K).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Following antigen retrieval in a microwave for 1 or 8 min in 0.01 M tri-sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) and 0.01 M Dako Target Retrieval Solution (pH 9; cat. no. S2367; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), 5-µm sections were blocked with 10% normal serum (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 20 min at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies, including mouse anti-pan-cytokeratin (AE1/3; cat. no. ab27988; 1:20; Abcam), anti-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)9 (F-69; 1:20; Kyowa Pharma Chemical Co., Ltd.) anti-membrane-type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP; F-86; 1:20; Kyowa Pharma Chemical Co., Ltd.), rabbit anti-Snail + SLUG (cat. no. ab180714; 1:200; Abcam), rabbit anti-RANKL (cat. no. bs-0747R; 1:100; Bioss) and anti-PTHrP (cat. no. 10817-1-AP; 1:100; Proteintech Group Inc.) overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with TBS, all sections were incubated with secondary antibody avidin-biotin complexes [mouse (cat. no. PK-6102)/rabbit (cat. no. PK-6101) ABC kit; blocking serum (normal serum, diluted with TBS), 1:75; biotinylated secondary antibody (diluted with normal serum), 1:200; reagent A (Avidin, ABC Elite) and reagent B (biotinylated HRP, ABC Elite, diluted by TBS), 1:55; Vector Laboratories, Inc.] for 1 h at room temperature followed by visualization with diaminobenzidine (DAB)/H2O2 mixed solution (Histofine DAB substrate; Nichirei Biosciences, Inc.). Images of the erosive area of the bone invasion region in the tissues were captured using a bright-field microscope. A total of ten images (magnification, ×40) were acquired for each mouse to assess the expression levels of MMP9, MT1-MMP, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP by IHC score. IHC score was calculated as follows: Percentage of positive cells score × intensity score. The percentage of positive cells score was defined as: 0 (<1%); 1 (1–24%); 2 (25–49%); 3 (50–74%); 4 (75–100%). The intensity score was defined as: 0, no staining; 1, light yellow color (weak staining); 2, brown color (moderate strong staining); and 3, dark brown color (strong staining) (25).

Microarray and bioinformatics analyses

RNA was extracted from cultured VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs to conduct microarray. RNA was first extracted by RNeasy mini spin columns (Qiagen, Inc.) and the quality was checked using a NanoDrop (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Subsequently, cDNA synthesis, cRNA labeling and amplification processed were conducted using the Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), and the purification of labeled cRNAs was conducted using RNeasy mini spin columns (Qiagen, Inc.). Finally, the microarray (SurePrint G3 Human 8×60K ver.3.0; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was scanned using a G2505C Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and bioinformatics analyses were performed. The GeneSpring GX 14.9 was used to determine the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in SCC-SCs compared with in VSCC-SCs. |LogFC|>1 was considered as the cut-off value (the dataset was uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus database, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?&acc=GSE164374). The upregulated DEGs that interact with MMP9, MT1-MMP, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP were examined by protein-to-protein interaction network (PPI) analysis using STRING (http://string-db.org/) and Cytoscape 3.7.2 (cytohubba; http://cytoscape.org/). A combined score >0.4 was considered as the cut-off value and the hub genes were selected according to the degree. The hub genes that were differentially expressed in SCC-SCs compared with in VSCC-SCs were analyzed by heatmap (a software plug-in within SangerBox; http://sangerbox.com). Finally, the differentially expressed hub genes that interact with MMP9, MT1-MMP, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP were depicted in a Venn plot.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The cell experiments were repeated three times, and the animal research was repeated on five independent mice. The parametric data are presented as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences among >2 groups followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The non-parametric data are presented as the median and IQR. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze the non-parametric data followed by Dunn's test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

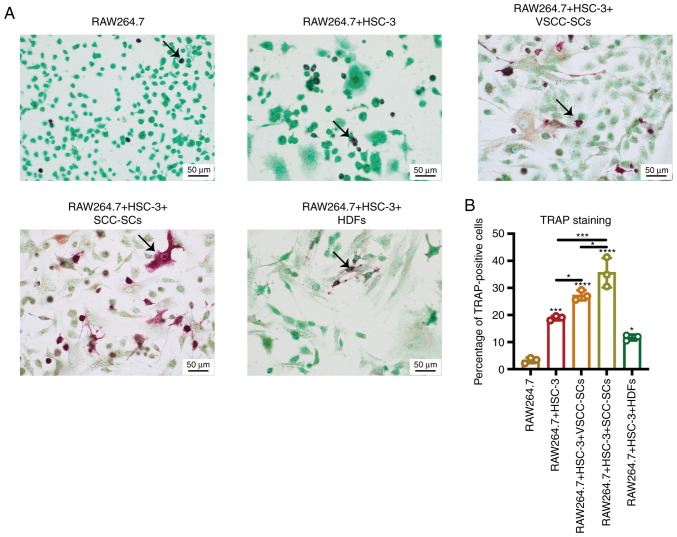

Both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promote the activation of osteoclasts in vitro

HSC-3 cells were selected as a cell model due to the fact that HSC-3 is a type of poorly-differentiated oral cancer cell line with obvious bone invasive ability that is widely used in bone invasion research. The RAW264.7 cell line was selected as a cell model as it is comprised of murine macrophages and is widely used in the research of bone invasion research (17). Firstly, TRAP staining was used to determine the percentage of TRAP-positive cells in different groups to determine the effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on osteoclast activation (Fig. 1). The percentage of TRAP-positive cells was highest in the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group, followed by the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group. The percentage of TRAP-positive cells in the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 group was slightly higher than that in the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + HDFs group, whereas it was markedly higher than that in the RAW264.7 group (Fig. 1B). In addition, the RAW264.7 and RAW264.7 + HSC-3 groups mainly contained round-shaped TRAP-positive cells; the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group mainly contained round-shaped TRAP-positive cells, but with several triangle- and spindle-shaped TRAP-positive cells; the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group mainly contained triangle- and spindle-shaped TRAP-positive cells and few round-shaped TRAP-positive cells; and the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + HDFs group mainly contained spindle- and round-shaped TRAP-positive cells (Fig. 1A). Finally, the sizes of the TRAP-positive cells in the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group were slightly larger than those in the RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group, and markedly larger than those in the RAW264.7, RAW264.7 + HSC-3 and RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + HDFs groups. There was little difference between the RAW264.7, RAW264.7 + HSC-3 and RAW264.7 + HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 1A). These findings indicated that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promoted the activation of osteoclasts by regulating their number, shape and size.

Figure 1.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the activation of osteoclasts in vitro. (A) TRAP staining was used to test the effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the activation of osteoclasts. The arrows indicate the TRAP-positive cells. (B) Semi-quantification of the percentage of positive osteoclasts in different groups of RAW264.7 cells. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. RAW264.7 or as indicated. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

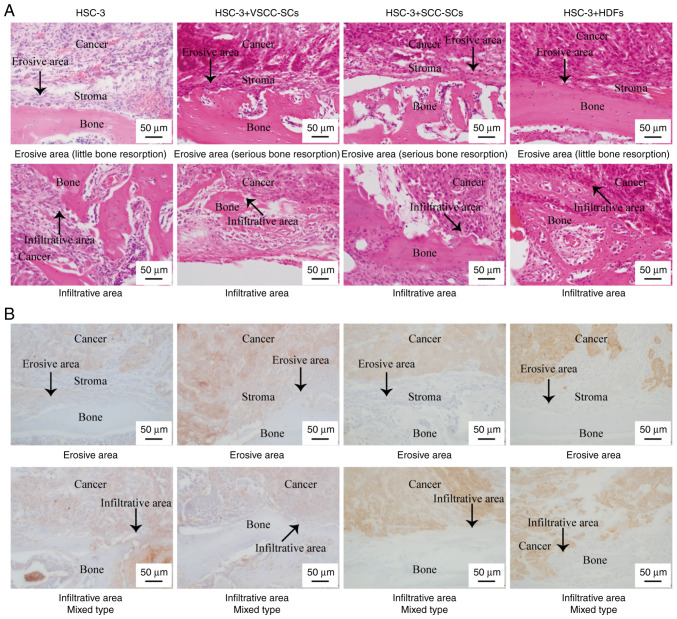

Effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on the bone resorption of HSC-3 cells in vivo

H&E and AE1/3 (pan-cytokeratin) staining were used to determine the effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the bone resorption of HSC-3 cells in vivo. Notably, AE1/3 (pan-cytokeratin) staining is used to detect cancer cells. Histologically, three types of bone invasion are recognized: Erosive, infiltrative and mixed. The erosive type of bone invasion is associated with a sharp transition between the cancer and bone, osteoclastic bone resorption, fibrosis along the cancer and the absence of bone islets within the cancer. The infiltrative type of bone invasion is associated with the formation of irregular nests and projections of cancer cells into the bone, and the presence of residual bone islets inside the cancer. The mixed type includes both types of invasion in the cancer invasion region (26,27). In each group, some regions exhibited the stroma between the cancer and bone area, while some regions did not contain the stroma between the cancer region and bone region. The results revealed that the four groups exhibited a mixed type of bone invasion (Fig. 2A and B). In both erosive and infiltrative areas, the bone resorption degree of HSC-3 + SCC-SCs was the most serious according to bone resorption morphology, followed by HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs. There was little difference between the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 2A). These data indicated that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promoted the bone resorption of HSC-3 in vivo, and SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect than VSCC-SCs.

Figure 2.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the bone resorption of HSC-3 cells in vivo using (A) hematoxylin and eosin, and (B) AE1/3 (pan-cytokeratin) staining. The arrows indicate the erosive area. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

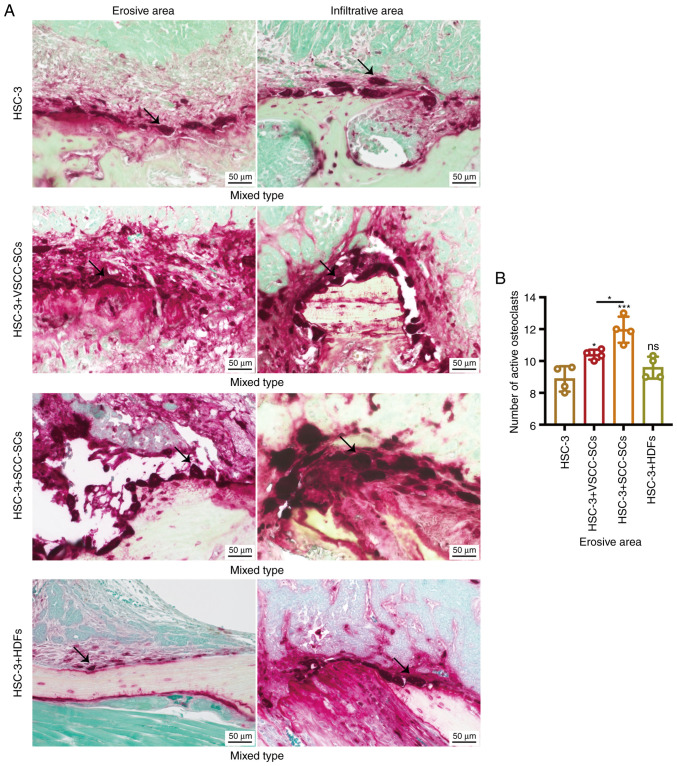

Both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promote osteoclast activation in the bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo

TRAP staining was used to determine the number of active, multi-nucleated osteoclasts to determine the effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo. The sizes of giant osteoclasts in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group were slightly larger than those in the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs and HSC-3 groups, whereas they were markedly larger than those in the HSC-3 + HDFs group in both erosive and infiltrative areas (Fig. 3A). In addition, the number of active multi-nucleated osteoclasts in the erosive area in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group was slightly higher than that in HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group, whereas it was markedly higher than those in the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups in both erosive and infiltrative areas; all of these comparisons in the erosive area were significantly different (Fig. 3A and B). In erosive areas, the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group mainly contained triangle-shaped osteoclasts, and the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs and HSC-3 groups contained triangle-, ellipse- and round-shaped osteoclasts, whereas there were only ellipse-shaped osteoclasts in the HSC-3 + HDFs group (Fig. 3A). In infiltrative areas, the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group mainly contained round-shaped osteoclasts and the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group contained triangle-, ellipse- and round-shaped osteoclasts, whereas there were ellipse- and round-shaped osteoclasts in the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 3A). These data suggested that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promoted the activation of osteoclasts in bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo, and SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect than VSCC-SCs.

Figure 3.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the activation of osteoclasts in the bone invasion areas of HSC-3 cells in vivo. (A) TRAP staining was used to determine the number of active multi-nucleated osteoclasts on bone surfaces. The arrows indicate the active multi-nucleated osteoclasts. (B) Semi-quantification of active multi-nucleated osteoclasts in the erosive part of different groups of HSC-3 cells. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n=4. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. nsP>0.05, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs. HSC-3 or as indicated. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

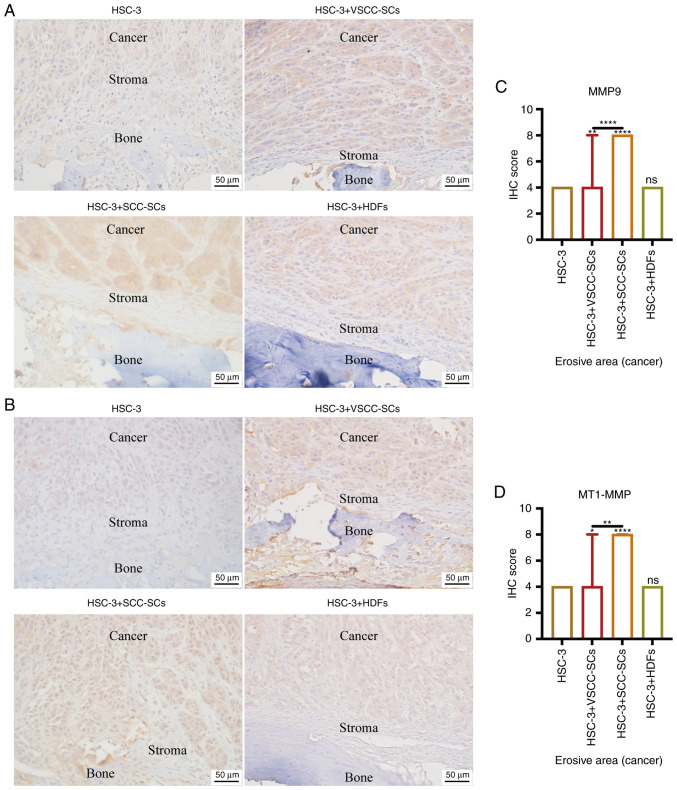

Both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promote HSC-3 invasion in bone invasion regions in vivo by enhancing MMP9 and MT1-MMP expression

IHC was used to determine the expression levels of MMP9 and MT1-MMP in bone invasion areas, and to assess the effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the invasion of HSC-3 cells (Fig. 4A and B). The IHC scores of MMP9 and MT1-MMP in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group were slightly higher than those in the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group, and markedly higher than those in the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups, and these findings were significantly different, whereas there was little difference between the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 4C and D). These data suggested that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promoted the invasion of HSC-3 cells in bone invasion regions, and SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect than VSCC-SCs, whereas HDFs had a minimal effect.

Figure 4.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the invasion of HSC-3 cells in bone invasion regions. IHC was used to determine the expression levels of (A) MMP9 and (B) MT1-MMP. Semi-quantification of (C) MMP9 and (D) MT1-MMP expression levels in bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells. Data are shown as the median and IQR, n=4. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test. nsP>0.05, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. HSC-3 or as indicated. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MT1-MMP, membrane-type 1 MMP; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

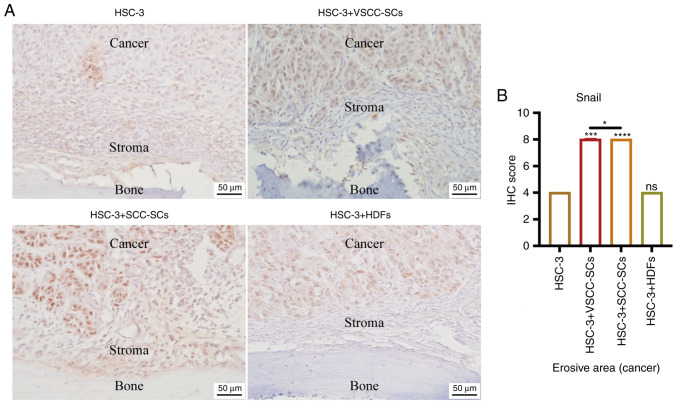

Both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of HSC-3 cells in bone invasion regions in vivo

IHC was used to detect the expression levels of Snail to determine the effect of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the EMT of HSC-3 in bone invasion areas (Fig. 5A). The IHC score of Snail was highest in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group, closely followed by the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group. There was little difference between the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 5B). These data indicated that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs may enhance the EMT of HSC-3 cells in bone invasion regions, and SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect than VSCC-SCs, whereas HDFs had a minimal effect.

Figure 5.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HSC-3 cells in bone invasion regions. (A) IHC was used to determine the expression levels of Snail. (B) Semi-quantification of Snail expression levels in the bone invasion regions of different groups of HSC-3 cells. Data are shown as the median and IQR, n=4. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test. nsP>0.05, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. HSC-3 or as indicated. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; IHC, immunohistochemistry; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

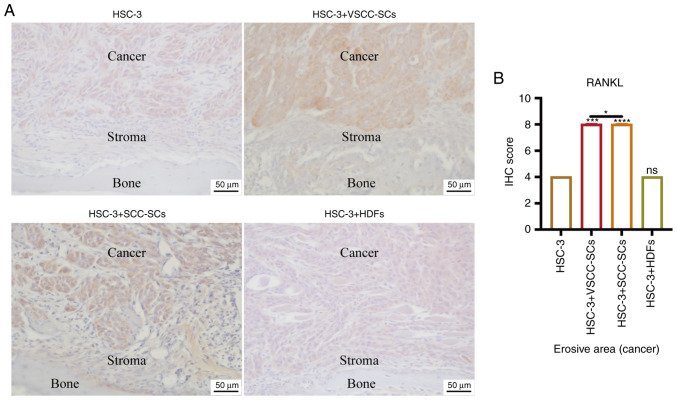

Both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promote RANKL expression in cancer and stroma areas in the bone invasion region of HSC-3 cells in vivo

IHC was used to determine the expression levels of RANKL in cancer and stroma areas to determine the effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on the activation of osteoclasts in the bone invasion areas of HSC-3 cells (Fig. 6A). Semi-quantification of IHC scores was only conducted in the erosive area to present the protein expression levels in cancer regions. The protein expression levels in stroma regions were only compared by intensity rather than by semi-quantification of IHC score. In stroma areas, the intensities of RANKL in HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs and HSC-3 + SCC-SCs groups were slightly higher than those in the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 6A). In cancer areas, the IHC score of RANKL was highest in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group, followed by the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group; there was little difference between the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 6B). These data demonstrated that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promoted RANKL expression in cancer and stroma areas in the bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo, and that SCC-SCs had a stronger effect than VSCC-SCs, whereas HDFs had a minimal effect.

Figure 6.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on RANKL expression in cancer and stroma areas in bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo. (A) IHC was used to determine RANKL expression in cancer and stroma areas. (B) Semi-quantification of RANKL expression in different groups of HSC-3 cells. Data are shown as the median and IQR, n=4. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test. nsP>0.05, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. HSC-3 or as indicated. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

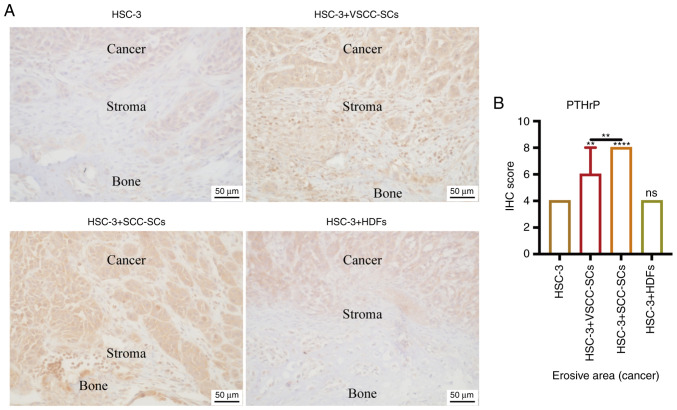

Both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promote PTHrP expression in cancer and stroma areas in bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo

Given that RANKL expression is regulated by PTHrP (12), IHC was used to determine the expression levels of PTHrP in cancer and stroma areas in bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells (Fig. 7A). Semi-quantification of IHC scores was only conducted in the erosive area to present the protein expression levels in cancer regions. The protein expression levels in stroma regions were only compared by intensity rather than by semi-quantification of IHC score. In stroma areas, the intensities of PTHrP in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs and HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs groups were markedly higher than those in the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 7A). In cancer areas, the IHC score of PTHrP in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs was slightly higher than that in the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group, but was markedly higher than that in the HSC-3 + HDFs and HSC-3 groups; these findings were significantly different. There was little difference between the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups (Fig. 7B). These data suggested that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs promoted PTHrP expression in cancer and stroma areas in the bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo, and SCC-SCs had a greater effect than VSCC-SCs, whereas HDFs exerted a minimal effect.

Figure 7.

Effects of VSCC-SCs, SCC-SCs and HDFs on PTHrP in cancer and stroma areas in the bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo. (A) IHC was used to determine PTHrP expression in different groups of HSC-3 cells. (B) Semi-quantification of PTHrP expression in different groups of HSC-3 cells. Data are shown as the median and IQR, n=4. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test. nsP>0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. HSC-3 or as indicated. HDFs, human dermal fibroblasts; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related peptide; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

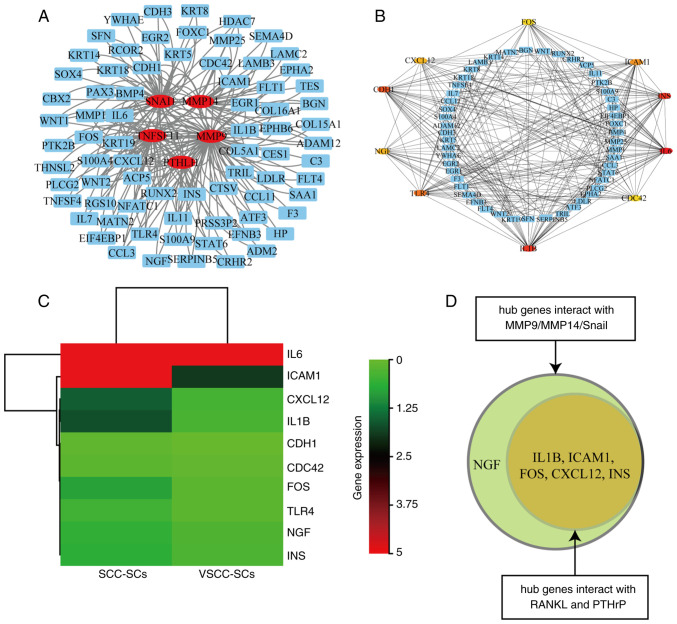

IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12, INS and NGF may underlie the differential effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on bone invasion in OSCC

Microarray data were used to analyze the upregulated DEGs in SCC-SCs compared with in VSCC-SCs. The upregulated DEGs that could interact with MMP9, MMP14, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP were identified by a PPI network (Fig. 8A). The hub genes in these upregulated DEGs were also identified by PPI. The results revealed that IL6, ICAM1, CXCL12, IL1B, CDH1, CDC42, FOS, TLR4, NGF and INS were hub genes (Fig. 8B). The hub genes that were differentially expressed in VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs were then analyzed by heatmap, which indicated that IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12, INS and NGF were differentially expressed in SCC-SCs compared with in VSCC-SCs (Fig. 8C). In addition, IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12 and INS can interact with MMP9, MMP14, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP, whereas NGF can only interact with MMP9, MMP14 and Snail, according to the results of PPI and the Venn diagram (Fig. 8D). These data suggested that IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12, INS and NGF may underlie the differential effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on bone invasion of OSCC.

Figure 8.

Identification of potential genes that underlie the differential effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on bone invasion in OSCC. (A) PPI analysis identified the upregulated DEGs in SCC-SCs that could interact with MMP9, MMP14, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP. (B) PPI analysis identified the hub genes in the upregulated DEGs in SCC-SCs that could interact with MMP9, MMP14, Snail, RANKL and PTHrP. (C) Hub genes differentially expressed in VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs were examined using a heatmap. (D) Relevant genes that the differentially expressed hub genes could interact with are presented using a Venn plot. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; PPI, protein-protein interaction; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related peptide; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand; SCC-SC, squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells; VSCC-SC, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma-associated stromal cells.

Discussion

Invasion of OSCC into the nearby maxilla and mandible can promote progression of the tumor stage. Bone invasion is diagnosed by CT and MRI, and the treatment method is bone resection (28–30). There are three types of OSCC bone invasion: Erosive, infiltrative and mixed (26,27). Our research group previously reported that both VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs could promote the bone invasion of HSC-2 and HSC-3 cells. Notably, SCC-SCs were revealed to have a better promoting effect than VSCC-SCs on the bone invasion of HSC-2 and HSC-3 cells, whereas HDFs exerted a minimal effect; however, these two studies did not assess the type of bone invasion and the relevant regulatory mechanisms (21,22). The present study mainly focused on the type of invasion and the potential regulatory mechanism. The results revealed that the HSC-3, HSC-3 + SCC-SCs, HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs and HSC-3 + HDFs groups exhibited mixed-type bone invasion. In addition, both SCC-SCs and VSCC-SCs promoted the bone invasion of HSC-3 cells in vitro and in vivo, and SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect than VSCC-SCs, whereas HDFs had a minimal effect. A previous study indicated that there are numerous giant osteoclasts with different shapes on the bone surfaces in bone invasion areas of OSCC (31). In the present study, the giant osteoclasts in the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group were slightly larger than those in the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs and HSC-3 groups, but were markedly larger than those in the HSC-3 + HDFs group, in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, the size of osteoclasts could influence bone resorption in OSCC. In addition, the HSC-3 + SCC-SCs group contained triangle- and round-shaped osteoclasts, whereas the HSC-3 + VSCC-SCs group contained triangle-, ellipse- and round-shaped osteoclasts, and there were ellipse- and round-shaped osteoclasts in the HSC-3 and HSC-3 + HDFs groups. With regard to their bone invasion degree, the present findings indicated that the triangle-shaped osteoclasts have the best bone resorption ability, followed by ellipse-shaped osteoclasts, whereas the round-shaped osteoclasts exert a minimal effect on the bone resorption. Triangle-shaped osteoclasts are activated multinucleated osteoclasts that are formed by the fusion of several osteoclasts; therefore, the triangle-shaped osteoclasts have the best bone invasion ability. Ellipse-shaped osteoclasts are a kind of spindle-shaped osteoclast, which are more active than normal osteoclasts but are not formed by the fusion of several osteoclasts; therefore, the bone invasion ability of ellipse-shaped osteoclasts is lower than that of triangle-shaped osteoclasts. Round-shaped osteoclasts are similar to the shape of normal osteoclasts and have the lowest bone invasion ability. All of these findings have been indirectly confirmed by a previous study (30). Therefore, the shape of the osteoclasts may be associated with bone resorption. In conclusion, both SCC-SCs and VSCC-SCs influenced the bone invasion of OSCC by regulating the number, size and shape of giant osteoclasts on bone surfaces.

The bone invasion of OSCC is divided into three phases: Initial phase, bone resorption phase and final phase (32). In the initial phase, MMPs serve a significant role in the crosstalk between cancer cells and bone-relevant cells by promoting cancer cells to enter into soft tissues or bone marrow spaces (33,34). Furthermore, cancer cells can migrate into the TME to invade the bone tissues via EMT (35). P130cas is one factor that can promote the bone invasion of OSCC by regulating EMT (36). Furthermore, TGF-β1 can promote EMT and subsequently promote the OSCC bone invasion by enhancing the activation of osteoclasts (37). Given that both cancer and stroma have an effect on the bone invasion of OSCC, semi-quantification of IHC scores was only conducted in the erosive area to present the relevant protein expression levels in cancer regions. The relevant protein expression levels in stroma regions were only compared by intensity rather than by semi-quantification of IHC score. In the present study, SCC-SCs and VSCC-SCs promoted MMP9 and MT1-MMP expression, and the EMT of HSC-3 cells in bone invasion areas, with SCC-SCs having a more prominent effect. Therefore, VSCC-SCs and especially SCC-SCs may promote the initial phase of bone invasion of OSCC, whereas HDFs have a minimal effect.

The second phase of bone invasion of OSCC is bone resorption mediated by osteoclasts (32). Osteoclast formation is regulated by colony-stimulating factor 1 and RANKL (38). OSCC bone invasion could be induced by the expression of RANKL, which promotes osteoclast formation in the TME (39). The inhibition of RANK and RANKL has been shown to suppress the bone invasion of OSCC by inhibiting osteoclast formation (40,41). A previous study also indicated that RANKL expression is regulated by PTHrP (42). Overexpression of PTHrP in OSCC has been reported to promote RANKL expression, which in turn may regulate the formation of osteoclasts in the TME (12,43). In the present study, SCC-SCs and VSCC-SCs promoted the expression levels of RANKL and PTHrP in cancer and stroma areas of bone invasion regions of HSC-3 cells in vivo, with SCC-SCs having a more prominent effect. Therefore, VSCC-SCs and especially SCC-SCs may promote the bone resorption phase of bone invasion of OSCC, whereas HDFs have little effect. The present study only revealed that VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs could promote bone invasion by enhancing the expression levels of RANKL and PTHrP; however, whether the VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs regulate bone invasion of OSCC by PTHrP/RANKL pathways needs to be further investigated by using the RANKL and PTHrP inhibitor. In addition, due to the direct co-culture method used in the present study, protein or RNA could not be extracted from a certain cell or tissue type independently. Therefore, IHC was performed to determine the expression levels of the relevant proteins, which is not as accurate as western blotting and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

The findings of microarray and bioinformatics analysis suggested that IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12, INS and NGF may underlie the differential effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on bone invasion in OSCC. A previous study indicated that IL1B is closely associated with the EMT of human gastric adenocarcinoma cells, which also promotes the formation of multinucleated osteoclasts by enhancing RANKL-dependent adseverin expression (44,45). ICAM1 has been reported to be closely associated with MMP9 and MMP14 expression in breast cancer, and soluble ICAM1 and RANKL have synergistic effects on the activation of osteoclasts (46–49). PTHrP can also regulate ICAM1 expression by influencing TGF-β (50). The Fos proto-oncogene, FOS, has also been reported to be closely associated with the expression of MMP9 in breast cancer and in the EMT process of hepatocellular carcinoma (51,52), and a recent study indicated that umbelliferone may inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclast formation by suppressing the Akt-c-Fos-NFATc1 signaling pathway (53). In addition, PTHrP can promote FOS expression in cementoblasts (54). INS has been poorly investigated in the bone invasion of OSCC. CCXCL12 and CXCR4 have been shown to serve a critical role in the invasion of OSCC and EMT of breast cancer (55,56), and CXCL12 may also enhance RANKL- and TNF-α-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption (57). Therefore, CXCL12 may regulate the initial and bone resorption phases of bone invasion of OSCC. A recent study suggested that NGF promotes MMP9 expression indirectly in colorectal cancer metastasis (58), and the NGF-TrkA axis enhances EMT and EGFR inhibitor resistance by activating the STAT3 signaling pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (59). In addition, NGF has been demonstrated to be closely associated with bone resorption in periodontitis (60). It is clear that these aforementioned factors have the potential to regulate the bone invasion of OSCC. However, all of these potential genes were only analyzed by microarray, which represents their mRNA expression levels in the stromal cells. The protein expression levels of these potential genes in stromal cells need to be further confirmed by western blotting.

In conclusion, both SCC-SCs and VSCC-SCs promoted the bone invasion of OSCC by regulating the initial and bone resorption phases, and SCC-SCs had a more prominent effect. IL1B, ICAM1, FOS, CXCL12, INS and NGF may underlie the differential effects of VSCC-SCs and SCC-SCs on the bone invasion of OSCC. These findings illuminate the potential regulatory mechanisms of bone invasion in OSCC, which could contribute to the treatment and prognosis of patients with OSCC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant nos. JP21K17089, JP19K19159, JP20K10178, JP20H03888 and JP21K10043).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The microarray data generated in the present study may be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE164374 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?&acc=GSE164374.

Authors' contributions

QS designed the outline of the study. QS, KT, HK, MWO, YI, SS, SF, KN and HN conducted experiments and data analysis. QS and KT were involved in the preparation of the manuscript. QS wrote the manuscript. KN and HN supervised the study, and contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revision. KT and HN confirmed the authenticity of all raw data. All authors have read and approve the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Okayama University (project identification code: 1703-042-001). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All animal experiments were conducted according to the relevant guidelines and regulations approved by the institutional committees at Okayama University (approval no. OKU-2017406).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacco AG, Cohen EE. Current treatment options for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3305–3313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura T, Shibahara T, Cui NH, Noma H. Patterns of mandibular invasion by gingival squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1489–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.05.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YL, Kuo SW, Fang KH, Hao SP. Prognostic impact of marginal mandibulectomy in the presence of superficial bone invasion and the nononcologic outcome. Head Neck. 2011;33:708–713. doi: 10.1002/hed.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:638–649. doi: 10.1038/nrg1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: Shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:292–304. doi: 10.1038/nri2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: What do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170:427–435. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okamoto M, Hiura K, Ohe G, Ohba Y, Terai K, Oshikawa T, Furuichi S, Nishikawa H, Moriyama K, Yoshida H, Sato M. Mechanism for bone invasion of oral cancer cells mediated by interleukin-6 in vitro and in vivo. Cancer. 2000;89:1966–1975. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001101)89:9<1966::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tada T, Jimi E, Okamoto M, Ozeki S, Okabe K. Oral squamous cell carcinoma cells induce osteoclast differentiation by suppression of osteoprotegerin expression in osteoblasts. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:253–262. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono K, Akatsu T, Kugai N, Pilbeam CC, Raisz LG. The effect of deletion of cyclooxygenase-2, prostaglandin receptor EP2, or EP4 in bone marrow cells on osteoclasts induced by mouse mammary cancer cell lines. Bone. 2003;33:798–804. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimi E, Furuta H, Matsuo K, Tominaga K, Takahashi T, Nakanishi O. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2011;17:462–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayamori K, Sakamoto K, Nakashima T, Takayanagi H, Morita K, Omura K, Nguyen ST, Miki Y, Iimura T, Himeno A, et al. Roles of interleukin-6 and parathyroid hormone-related peptide in osteoclast formation associated with oral cancers: Significance of interleukin-6 synthesized by stromal cells in response to cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:968–980. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valkenburg KC, de Groot AE, Pienta KJ. Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:366–381. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei LY, Lee JJ, Yeh CY, Yang CJ, Kok SH, Ko JY, Tsai FC, Chia JS. Reciprocal activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts and oral squamous carcinoma cells through CXCL1. Oral Oncol. 2019;88:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.An YZ, Cho E, Ling J, Zhang X. The Axin2-snail axis promotes bone invasion by activating cancer-associated fibroblasts in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:987. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elmusrati AA, Pilborough AE, Khurram SA, Lambert DW. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote bone invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:867–875. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel SG, Shah JP. TNM staging of cancers of the head and neck: Striving for uniformity among diversity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:242–258. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.4.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiro RH, Guillamondegui O, Jr, Paulino AF, Huvos AG. Pattern of invasion and margin assessment in patients with oral tongue cancer. Head Neck. 1999;21:408–413. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199908)21:5<408::AID-HED5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussein MR, Cullen K. Molecular biomarkers in HNSCC: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2001;1:116–124. doi: 10.1586/14737140.1.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takabatake K, Kawai H, Omori H, Qiusheng S, Oo MW, Sukegawa S, Nakano K, Tsujigiwa H, Nagatsuka H. Impact of the stroma on the biological characteristics of the parenchyma in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7714. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shan Q, Takabatake K, Omori H, Kawai H, Oo MW, Nakano K, Ibaragi S, Sasaki A, Nagatsuka H. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment promote the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2021;59:72. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2021.5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tohyama R, Kayamori K, Sato K, Hamagaki M, Sakamoto K, Yasuda H, Yamaguchi A. Establishment of a xenograft model to explore the mechanism of bone destruction by human oral cancers and its application to analysis of role of RANKL. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:356–364. doi: 10.1111/jop.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flecknell PA. 3rd edition. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2009. Laboratory Animal Anesthesia. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuang FH, Hsue SS, Wu CW, Chen YK. Immuno histochemical expression of RANKL, RANK, and OPG in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:753–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw RJ, Brown JS, Woolgar JA, Lowe D, Rogers SN, Vaughan ED. The influence of the pattern of mandibular invasion on recurrence and survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2004;26:861–869. doi: 10.1002/hed.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JS, Lowe D, Kalavrezos N, D'Souza J, Magennis P, Woolgar J. Patterns of invasion and routes of tumor entry into the mandible by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2002;24:370–383. doi: 10.1002/hed.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uribe S, Rojas LA, Rosas CF. Accuracy of imaging methods for detection of bone tissue invasion in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42:20120346. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibo T, Yamada SI, Kawamoto M, Uehara T, Kurita H. Immunohistochemical investigation of predictive biomarkers for mandibular bone invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26:2381–2389. doi: 10.1007/s12253-020-00826-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel RS, Dirven R, Clark JR, Swinson BD, Gao K, O'Brien CJ. The prognostic impact of extent of bone invasion and extent of bone resection in oral carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:780–785. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816422bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quan J, Hou Y, Long W, Ye S, Wang Z. Characterization of different osteoclast phenotypes in the progression of bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:1043–1051. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quan J, Johnson NW, Zhou G, Parsons PG, Boyle GM, Gao J. Potential molecular targets for inhibiting bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma: A review of mechanisms. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quan J, Zhou C, Johnson NW, Francis G, Dahlstrom JE, Gao J. Molecular pathways involved in crosstalk between cancer cells, osteoblasts and osteoclasts in the invasion of bone by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology. 2012;44:221–227. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283513f3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodward JK, Holen I, Coleman RE, Buttle DJ. The roles of proteolytic enzymes in the development of tumour-induced bone disease in breast and prostate cancer. Bone. 2007;41:912–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Pluijm G. Epithelial plasticity, cancer stem cells and bone metastasis formation. Bone. 2011;48:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yaginuma T, Gao J, Nagata K, Muroya R, Fei H, Nagano H, Chishaki S, Matsubara T, Kokabu S, Matsuo K, et al. p130Cas induces bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma by regulating tumor epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell proliferation. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1038–1048. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quan J, Elhousiny M, Johnson NW, Gao J. Transforming growth factor-β1 treatment of oral cancer induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes bone invasion via enhanced activity of osteoclasts. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:659–670. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9570-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raggatt LJ, Partridge NC. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25103–25108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.041087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambandam Y, Ethiraj P, Hathaway-Schrader JD, Novince CM, Panneerselvam E, Sundaram K, Reddy SV. Autoregulation of RANK ligand in oral squamous cell carcinoma tumor cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6125–6134. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin M, Matsuo K, Tada T, Fukushima H, Furuta H, Ozeki S, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K, Okamoto M, Jimi E. The inhibition of RANKL/RANK signaling by osteoprotegerin suppresses bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1634–1640. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Junior CR, Liu M, Li F, D'Silva NJ, Kirkwood KL. Oral squamous carcinoma cells secrete RANKL directly supporting osteolytic bone loss. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takayama Y, Mori T, Nomura T, Shibahara T, Sakamoto M. Parathyroid-related protein plays a critical role in bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:1387–1394. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin CK, Dirksen WP, Shu ST, Werbeck JL, Thudi NK, Yamaguchi M, Wolfe TD, Heller KN, Rosol TJ. Characterization of bone resorption in novel in vitro and in vivo models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Wang B, Xie J, Hou D, Zhang H, Huang H. Melatonin inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer cells via attenuation of IL-1β/NF-κB/MMP2/MMP9 signaling. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42:2221–2228. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Galli M, Shade Silver A, Lee W, Song Y, Mei Y, Bachus C, Glogauer M, McCulloch CA. IL1β and TNFα promote RANKL-dependent adseverin expression and osteoclastogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2018;131:213967. doi: 10.1242/jcs.213967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung TW, Choi H, Lee JM, Ha SH, Kwak CH, Abekura F, Park JY, Chang YC, Ha KT, Cho SH, et al. Oldenlandia diffusa suppresses metastatic potential through inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-9 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression via p38 and ERK1/2 MAPK pathways and induces apoptosis in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;195:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di D, Chen L, Wang L, Sun P, Liu Y, Xu Z, Ju J. Downregulation of human intercellular adhesion molecule-1 attenuates the metastatic ability in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:1541–1548. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Palacios V, Chung HY, Choi SJ, Sarmasik A, Kurihara N, Lee JW, Galson DL, Collins R, Roodman GD. Eosinophil chemotactic factor-L (ECF-L) enhances osteoclast formation by increasing in osteoclast precursors expression of LFA-1 and ICAM-1. Bone. 2007;40:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai CF, Chen JH, Wu CT, Chang PC, Wang SL, Yeh WL. Induction of osteoclast-like cell formation by leptin-induced soluble intercellular adhesion molecule secreted from cancer cells. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919846806. doi: 10.1177/1758835919846806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhatia V, Cao Y, Ko TC, Falzon M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein interacts with the transforming growth factor-β/bone morphogenetic protein-2/gremlin signaling pathway to regulate proinflammatory and profibrotic mediators in pancreatic acinar and stellate cells. Pancreas. 2016;45:659–670. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milde-Langosch K, Röder H, Andritzky B, Aslan B, Hemminger G, Brinkmann A, Bamberger CM, Löning T, Bamberger AM. The role of the AP-1 transcription factors c-Fos, FosB, Fra-1 and Fra-2 in the invasion process of mammary carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;86:139–152. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000032982.49024.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen SP, Liu BX, Xu J, Pei XF, Liao YJ, Yuan F, Zheng F. MiR-449a suppresses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by multiple targets. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:706. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1738-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwak SC, Baek JM, Lee CH, Yoon KH, Lee MS, Kim JY. Umbelliferone prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced bone loss and suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by attenuating Akt-c-Fos-NFATc1 signaling. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2427–2437. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.28609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berry JE, Ealba EL, Pettway GJ, Datta NS, Swanson EC, Somerman MJ, McCauley LK. JunB as a downstream mediator of PTHrP actions in cementoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:246–57. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rehman AO, Wang CY. CXCL12/SDF-1 alpha activates NF-kappaB and promotes oral cancer invasion through the Carma3/Bcl10/Malt1 complex. Int J Oral Sci. 2009;1:105–118. doi: 10.4248/IJOS.09059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang F, Takagaki Y, Yoshitomi Y, Ikeda T, Li J, Kitada M, Kumagai A, Kawakita E, Shi S, Kanasaki K, Koya D. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 accelerates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer metastasis via the CXCL12/CXCR4/mTOR axis. Cancer Res. 2019;79:735–746. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shima K, Kimura K, Ishida M, Kishikawa A, Ogawa S, Qi J, Shen WR, Ohori F, Noguchi T, Marahleh A, Kitaura H. C-X-C motif chemokine 12 enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in vivo. Calcif Tissue Int. 2018;103:431–442. doi: 10.1007/s00223-018-0435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lei Y, He X, Huang H, He Y, Lan J, Yang J, Liu W, Zhang T. Nerve growth factor orchestrates NGAL and matrix metalloproteinases activity to promote colorectal cancer metastasis. Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;24:34–47. doi: 10.1007/s12094-021-02666-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin C, Ren Z, Yang X, Yang R, Chen Y, Liu Z, Dai Z, Zhang Y, He Y, Zhang C, et al. Nerve growth factor (NGF)-TrkA axis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma triggers EMT and confers resistance to the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib. Cancer Lett. 2020;472:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaspersic R, Kovacic U, Glisovic S, Cör A, Skaleric U. Anti-NGF treatment reduces bone resorption in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:515–520. doi: 10.1177/0022034510363108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The microarray data generated in the present study may be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE164374 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?&acc=GSE164374.