Abstract

The direct metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization of arenes has emerged as a powerful tool for streamlining the synthesis of complex molecular scaffolds. However, despite the different chemical environments, the energy values of all C–H bonds are within a fairly narrow range; hence, the regioselective C–H bond functionalization poses a great challenge. The use of covalently bound directing groups is to date the most exploited approach to achieve regioselective C–H functionalization of arenes. However, the required installation and removal of those groups is a serious drawback. Recently, new strategies for regioselective metal-catalyzed distal C–H functionalization of arenes based on noncovalent forces (hydrogen bonds, Lewis acid–base interactions, ionic or electrostatic forces, etc.) have been developed to tackle these issues. Nowadays, these approaches have already showcased impressive advances. Therefore, the aim of this mini-review is to cover chronologically how these groundbreaking strategies evolved over the past decade.

1. Introduction

The transition metal (TM) catalyzed C–H functionalization has been recognized as an efficient synthetic approach to access molecular diversity.1 Other TM-catalyzed chemical transformations usually exploit coupling partners that create new C–C bonds without regioselectivity issues, e.g. cross-coupling reactions. On the contrary, the regioselective C–H bond transformations are challenging due to the energy values of the C–H bonds, which fall within a narrow range. Taking a historical perspective, one can safely conclude that the major breakthroughs in the area of TM-catalyzed C–H functionalization have been triggered by regio- and site-selective issues. The very early achievements in TM-catalyzed C–H functionalization date back to the end of the 19th century.2 The modern efforts in this area began in the 1970s with the implementation of irreversibly covalently bonded directing groups (DGs)3 and, later, of the transient directing groups (TDGs), which rely on the reversible covalent binding of an organocatalyst to a particular functional group of the substrate.4 These approaches have already showcased impressive advances in several transformations.5 Even though the DG-technology is unique in its ability to regioselectively functionalize C–H bonds, these methods are limited by the difficulty to install and then remove such groups after functionalization. Furthermore, the DG approaches have been especially successful for ortho-selective functionalization of arenes. Up to this stage, chemists had achieved satisfactory success in distal regioselective C–H functionalization by using a stoichiometric transient mediator6 or covalently bound templates.7 However, although allowing in many cases highly regioselective C–H functionalizations, the substrates have often been specifically designed for that purpose. Furthermore, the covalently bound templates suffer from the common drawback of laborious preinstallation and postremoval of covalently bounded DGs.

During the past decade, the use of noncovalent interactions emerged as a new tool to tackle regioselectivity or site-selectivity issues in TM-catalyzed C–H functionalization of arenes. This somehow biocatalytically inspired approach does not rely on the covalent installation of DGs thus lack their drawbacks. Instead, a noncovalent interaction is used to anchor the substrate to an exogenous template, which is used for positioning the reaction site in a favorable orientation relative to the catalytic center.8

The potential of these methodologies to control regio- and site-selectivity in the field of distal C–H functionalization of arenes has been intensively studied over the past decade.9 The efforts of a number of research groups led to impressive advances in this area and the toolset of noncovalent interactions is constantly growing (Figure 1). Given the above, there is a high demand of reviews that cover the topic and here in we aim to summarize and discuss the reported noncovalent concepts and strategies for regioselective C–H functionalization of arenes published over the past decade.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the advances in the use of noncovalent forces in TM-catalyzed arene C–H bond activation reactions.

2. Ir-Catalyzed C–H Activation

2.1. ortho-Selective Borylation Reactions

The utilization of the hydrogen bond (HB) as a noncovalent directing interaction for TM-catalyzed C–H activation was first demonstrated by Roosen et al.10 The authors achieved ortho-selective borylation of different N-Boc protected anilines by the use of bis(1,5-cyclooctadiene)di-μ-methoxydiiridium(I) as a catalyst and 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-dipyridyl (dtbpy) as a ligand (Scheme 1). Computational studies revealed that an HB interaction between the NHBoc proton and the oxygen atom from the boron pinacolate group coordinated to the Ir-catalyst guides the latter to the ortho-position of the substrates relative to the N-Boc substituent (TS1).

Scheme 1. Ir-Catalyzed ortho-Borylation of N-(Boc)-Anilines10.

In a consequent study, the authors reported the use of in situ borylation of the aniline nitrogen atom, with the additional advantage of performing the N–B bond formation, C–H activation, and hydrolysis of the N–B bond in a one-pot protocol (Scheme 2, top).11 The regioselectivity of the reaction was supposedly governed by the steric bulk provided by the Bpin group, thus leading to selective borylation at the less hindered ortho-position relative to the N-Bpin substituent. In some instances this method led to improved yields and decreased catalyst loadings as compared to the borylation of N-Boc protected anilines. The substrate scope was extended to different N-heterocycles such as (aza)indole, pyrrole, and pyrazole. For substrates with less acidic N–H bonds (indole, pyrrole) the addition of a tertiary amine was necessary to facilitate the in situ N–B bond formation. Subsequently, the authors demonstrated that this could be used to tune the selectivity by simply performing the reaction in the presence (C-3 selectivity) or absence (C-2 selectivity) of a base (Scheme 2, bottom).

Scheme 2. (top) Traceless N-Bpin-directed Borylation of Anilines and (bottom) Regioselective Borylation of Indole11.

In 2016 Bisht and Chattopadhyay reported the ortho-selective borylation of benzaldehydes based on the formation of a transient imine, acting as a directing group for the Ir-catalyst to activate the corresponding C–H bond (Scheme 3).12 Various mono- and bis-substituted benzaldehydes have been successfully borylated at the ortho-position in very good yields and excellent selectivities. The regiochemical outcome of the reaction was governed by two factors: steric bulk of the N-alkyl substituent and electron density of the ligand. In the case of ortho-selectivity, the increased steric bulk of tert-butyl amine was beneficial compared to less hindered amines (methyl- and isopropyl amine).

Scheme 3. Ir-Catalyzed ortho-Selective Borylation of Imine-Protected Aromatic Aldehydes12.

Li et al. designed bipyridine ligand 13 for the ortho-selective functionalization of aryl sulfides (Scheme 4).13 The Lewis acidic boryl group in the ligand is capable of forming a Lewis pair with the thioanisole sulfur atom, thus facilitating the positioning of the metal center next to the ortho-position (TS3). The authors confirmed the important role of the Lewis acid–base interaction for the high ortho-selectivity by several experiments, which revealed that the following factors exhibit a detrimental effect on the selectivity: (1) polarity of the solvent; (2) high temperature; (3) bulky substituents on the sulfur atom; (4) less Lewis acidic boryl groups; and (5) bipyridine ligands without or with a boryl group at the para-position.

Scheme 4. ortho-Selective Ir-Catalyzed Borylation of Thioanisoles13.

Selective ortho-C–H borylation of methylthiomethyl-protected phenol and aniline derivatives has been achieved by using bipyridine-type ligands bearing an electron-withdrawing substituent (Scheme 5).14 The authors suggested two possible reaction mechanisms—one based on a noncovalent Lewis acid–base interaction between the boryl ligand of the iridium catalyst and the substrate sulfur atom (TS4) and the other proceeding via coordination of the iridium center to the sulfur atom, which acts as a directing group (TS5).

Scheme 5. (top) ortho-Selective Ir-Catalyzed Borylation of Methylthiomethyl-Protected Phenol and Aniline Derivatives and (bottom) Proposed Reaction Mechanisms14.

Almost at the same time, Chattopadhyay et al. reported the ortho-selective borylation of phenol derivatives via traceless protection of the OH group as O-Bglycolate (Scheme 6).15 Initial experiments with para-substituted phenols and Bpin as a protecting group led to the formation of ortho-substituted products with high degree of regioselectivity for substrates possessing sufficiently large substituents at the para-position (larger than CN or F). Computational and experimental studies revealed the factors that affect the catalytic activity: (a) the electrostatic interaction between the partially positive bipyridine ligand and partially negative Bpin-protected OH group and (b) the steric hindrance imposed by the Bpin methyl groups. Based on these results, the authors managed to increase the ortho-selectivity (conditions A vs B, Scheme 6) by using the less sterically hindered diborane reagent B2eg2 (B2eg2 = 2,2′-bi(1,3,2-dioxaborolane)).

Scheme 6. Ir-Catalyzed ortho-Borylation of O-Bglycolate-Protected Phenols15.

Reek and co-workers reported the supramolecular iridium catalyst 23 for ortho-selective C–H borylation of secondary aromatic amides (Scheme 7).16 Based on DFT calculations the authors concluded that the catalyst operates by substrate preorganization as a result of H-bonding between the indole amide motif and the substrate oxygen atom (TS7). This strategy allowed the successful ortho-borylaytion of a variety of secondary aromatic amides having functional groups at different positions, including on a gram scale (22aa, 22ba).

Scheme 7. Ir-Catalyzed ortho-Selective Borylation of Aromatic Secondary Amides16.

2.2. meta-Selective Borylation Reactions

The first efforts toward meta-selective borylation were made by Kuninobu, Kanai, and co-workers, who designed a catalytic system comprising of a bipyridine unit for metal coordination and urea moiety as a substrate binding site (Scheme 8).17 A hydrogen bond interaction between the urea moiety in ligand 26 and a Lewis basic atom in the substrate allows the Ir-catalyst to activate selectively the C–H bond in meta-position (TS8). This system was found to be applicable for a broad range of substrates, including different (hetero)aromatic amides, esters, and phosphorus compounds (phosphonates, phosphonic diamide, phosphine oxides).

Scheme 8. Ir-Catalyzed meta-Selective C–H Borylation of (Hetero)Aromatic Amides, Esters, and P(V)-Compounds17.

Bisht and Chattopadhyay achieved meta-borylation of a series of benzaldehydes using a strategy described in the previous subsection (Scheme 3).12 In contrast to the ortho-selective borylation, which was promoted by the steric bulk of the amine, an enhancement of the meta-selectivity was observed with less bulky substituents: Me > i-Pr > t-Bu. In addition, the application of electron-rich ligand such as 3,4,7,8-tetramethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (TMP) was crucial for the improvement of both yield and meta-selectivity. Based on this experimental findings, the authors proposed that the origin of meta-selectivity is due to the formation of transition structure TS9, which features a favorable electrostatic interaction between the Ir-complex and the substrate, together with a Lewis pair formation between the boryl boron atom and the imine nitrogen (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9. Ir-Catalyzed meta-Selective Borylation of Substituted Benzaldehydes12.

A noncovalent ionic pair approach for distal meta-functionalization of arenes was developed by the Phipps group.18 The devised strategy relied on the formation of ionic pair between a bipyridine ligand bearing a sulfonate anion (38) and a cationic ammonium group attached to the substrate (Scheme 10A). This allowed the Ir-catalyst to activate the meta-position of a variety of quaternized benzylamine and aniline derivatives with high degree of regioselectivity. Later on, the ion pair-directed meta-borylation was proved viable even when the ammonium group was attached to the arene by a longer and thus more flexible carbon chain (Scheme 10B).19 In further studies, the substrate scope of the ion-pair-directed methodology was successfully extended to aromatic systems bearing phosphonium group as a cation component (Scheme 10C).20

Scheme 10. Ir-Catalyzed Ion Pair-Directed Borylation of (A) Quaternized Benzylamine Derivatives;18 (B) Quaternized Phenethylamines and Phenylpropylamines;19 (C) Aromatic Phosphonium Salts20.

The bipyridine/sulfonate ligand 38 was also utilized as a potent H-bond acceptor for the selective meta-borylation of arenes bearing trifluoroacetylated amine groups.21 This “hydrogen-bond accepting mode” provided effective regiocontrol over substrates bearing different carbon chains (up to three carbons) between the nitrogen atom and the aromatic ring (Scheme 11). The borylation of derivatives with alkyl chains longer than three carbons was inefficient resulting in poor regioselectivity. These results were attributed to the high entropic cost associated with an organized transition structure for substrates with increased flexibility.

Scheme 11. Ir-Catalyzed Hydrogen Bond-Directed C–H Borylation of Benzylamine-, Phenethylamine-, and Phenylpropylamine-Derived Amides21.

A meta-selective borylation governed by cation−π noncovalent interaction between aromatic amides and L-shaped bipyridine/quinolone ligand 47 was developed by Bisht et al. (Scheme 12).22 A range of different N-substituted (hetero)aromatic amides has been successfully borylated at the meta-position with high degree of regioselectivity.

Scheme 12. Site-Selective C–H Borylation of (Hetero)Aromatic Amides Directed by Cation−π Noncovalent Interaction22.

A meta-selective C–H borylation of pyridines and benzamides was achieved with bifunctional catalysts.23 A Lewis acidic alkylaluminum 59 (Scheme 13) or alkylboron-based 65 (Scheme 14) moiety was used to anchor the ligand to Lewis basic aminocarbonyl or sp2-hybridized nitrogen, respectively, while bpy or phenanthroline moieties attached to a linker were used to guide the Ir-catalysts to the desired meta-position.

Scheme 13. meta-Selective C–H Borylation of (Hetero)Aromatic Amides Directed by an Ir/Al Bifunctional Catalyst23.

Scheme 14. Site-Selective C–H Borylation of Pyridines Directed by an Ir/B Bifunctional Catalyst23.

2.3. para-Selective Borylation Reactions

A bimetallic approach24 for para-selective functionalization of (hetero)arenes was developed by Yang et al.25 In order to achieve the desired selectivity, the authors designed a system based on cooperative iridium/aluminum catalysis (Scheme 15). An aluminum Lewis acid catalyst was employed to fulfill two essential tasks: (1) to form a Lewis acid–base pair with the substrate for increased reactivity; (2) to provide steric hindrance around the ortho- and meta-postions for effective regiocontrol. By using the commercially available Lewis acid 69 and the bipyridine ligand 70 a series of benzamide derivatives was successfully borylated at para-position with good to excellent selectivities (Scheme 15). The regioselectivity was influenced by the size of the substituents on the amide nitrogen and the nature of the substituents on the arene ring. The method was furthermore employed for the C–H borylation of several pyridine derivatives. However, the same catalytic system was effective only in a limited number of cases, thus an additional optimization of the Lewis acid and Ir-ligand was undertaken. The introduction of the bulky iso-butyl substituent, instead of methyl group, on the Al-center proved useful, providing an improved C4-selectivity (Scheme 16).

Scheme 15. para-Selective Borylation of (Hetero)Aromatic Amides Directed by Cooperative Ir/Al Catalysis25.

Scheme 16. Site-Selective C–H Borylation of Pyridines Directed by Cooperative Ir/Al Catalysis25.

Hoque et al.26 achieved para-selective borylation of (hetero)aromatic esters by exploiting a strategy based on the cooperation of two metals. An L-shape ligand 47 was designed to recognize the ester functionality through a noncovalent O–M–O interaction and simultaneously to deliver the Ir-catalyst next to the para-position with high degree of selectivity (Scheme 17). A K+ ion was found to provide the best interaction with the carbonyl oxygen, which was identified as the main factor for efficient regiocontrol.

Scheme 17. Site-Selective C–H Borylation of (Hetero)Aromatic Esters Directed by Noncovalent (C=O···K—O) Interaction26.

Mihai et al.27 and Bastidas et al.28 employed essentially the same approach to achieve para-selective Ir-catalyzed C–H borylation of a variety of ortho-substituted arenes. A bulky tetraalkyl ammonium cation, was utilized as a “steric shield”, creating highly sterically congested environment around the substrate anion, thus avoiding undesired C–H activations at ortho- and meta-positions (Scheme 18). In this manner, a wide range of ortho-substituted sulfates, sulfamates, and sulfonates were borylayed at para-positions with good to excellent regioselectivities.27,28

Scheme 18. para-Selective C–H Borylation of Aniline, Benzylamine, Phenol, and Benzyl Alcohol Derivatives Enabled by Ion-Pairing with a Bulky Countercation27.

3. Pd-Catalyzed C–H Activation

The impressive regioselectivities outlined in the studies discussed so far were only possible because of the high reactivity of the iridium catalysts in borylation reactions, which allows this transformation to be efficiently catalyzed under mild reaction conditions and provides the right environment for the weak noncovalent interactions to sustain. By contrast, the direct formation of C–C bonds via Pd catalyzed C–H activation requires harsher reaction conditions, thus limiting the number of noncovalent interactions that can be employed.

Zhang, Tanaka, and Yu have addressed this problem by making use of a reversible metal coordination chemistry to direct selectively the metal near the desired aromatic position.29 For this purpose, a dual-action bis(pyridine-3-sulfonamide) template 96 was designed as to coordinate two metal centers simultaneously (Scheme 19B). The bis-sulfonamide moiety serves to chelate the first metal center, which in turn anchors the substrate to the template, while the C3 pyridyl group in 96 plays the role of a noncovalently bound DG that coordinates the active catalyst (Scheme 19C). The concept was found to be efficient for the remote, site-selective olefination of various substituted 3-phenylpyridines. Notably, high selectivities were achieved using catalytic amounts of the template (20 mol %) even at high temperatures (Scheme 19A).

Scheme 19. (A) Pd-Catalyzed Site-Selective C–H Olefination of 3-Phenylpyridines; (B) Structure of the Bifunctional Template; (C) Hypothetical Mode of Action29.

The authors tested the feasibility of this approach for site-selective C–H activation of other classes of heterocyclic compounds.29 However, the bis(pyridine-3-sulfonamide) 96 was found to be inefficient for quinoline substrates. Nevertheless, the bimetallic approach still provided an effective solution by the application of nitrile-based templates. In these assemblies, a tridentate ligand 99 was used to anchor the first metal center and to provide steric hindrance, while the active catalyst is relayed selectively to the remote C5–H bond by a directing CN-group in the side arm (Scheme 20). The utility of this approach has been additionally demonstrated for the functionalization of other heterocycles such as quinoxaline, benzoxazole, and benzothiazole.

Scheme 20. Pd-Catalyzed Site-Selective C–H Olefination of Quinolines and Other Heterocycles29.

Maiti and co-workers undertook an intensive screening of bifunctional templates, which can promote Pd-catalyzed site-selective olefination of heterocycles in a similar manner. Their studies identified the bifunctional template 103 as an effective promoter of meta-selective C–H activation of 3-phenylpyridine derivatives, while template 104 was effective for quinoline substrates (Figure 2).30

Figure 2.

Templates for Pd-catalyzed site-selective olefination of heterocycles developed by the Maiti group.30

In a further study, Maiti and co-workers reported a structure optimization of the 2,6-disubstituted pyridine bis-amide ligands that allowed the distal alkylation of fused nitrogen heterocycles with allylic alcohols (Scheme 21).31 The newly designed template 107 proved effective for the Pd-catalyzed site-selective alkylation of various heterocycles such as quinolines, benzoxazoles, and (benzo)thiazoles.

Scheme 21. Pd-Catalyzed Distal Alkylation of Different Heterocycles31.

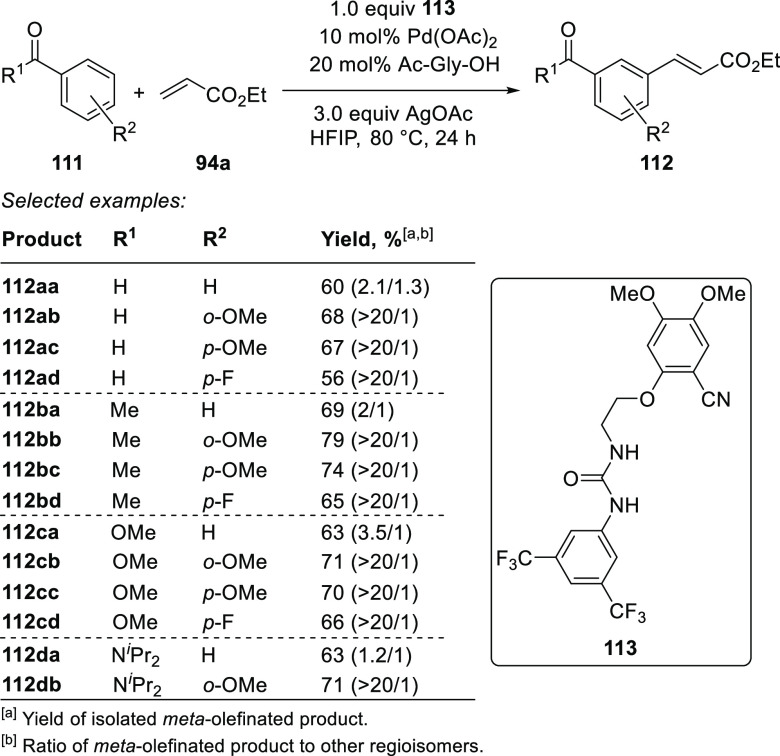

Recently, Jin, Xu, and co-workers developed a Pd-catalyzed meta-selective C–H olefination of aromatic carbonyl compounds directed by intermolecular hydrogen-bonding.32 The authors achieved the desired regioselectivity by the combination of an N,N′-disubstituted urea scaffold as an H-bond donor for substrate binding and a salicylonitrile-bearing tether as a DG (Scheme 22). The template was found to induce high levels of selectivity with broad range of substrates, such as aromatic ketones, aldehydes, benzoate esters, and benzamides.

Scheme 22. Pd-Catalyzed meta-Olefination of Aromatic Aldehydes, Ketones, Benzoate Esters, and Benzamides32.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, although in its infancy, the noncovalent control in C–H functionalization has already showed impressive advances. However, we would like to outline several future directions. Despite the few examples of Pd-catalyzed regioselective C–H activations highlighted above, most of these new synthetic paths fall in the realm of Ir-catalyzed borylation due to its mild reaction conditions. Hence, there is an obvious need for organic chemists to move out from this comfort zone and to focus more efforts on the direct distal formation of C–C bonds. So far other metals that could possibly provide further breakthroughs in this area (e.g., Ru, Co, etc.) have received less research focus and, hence, require additional diligence. Over the last years, we have seen many new noncovalent strategies for distal C–H functionalization of arenes with potential applications in organic synthesis. However, despite few examples, the applications of these methodologies for C–H functionalization of substrates that possess high conformational freedom is still underdeveloped.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National

Scientific

Program “VIHREN” (grant  ). The project leading to this application

has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020

research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 951996.

). The project leading to this application

has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020

research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 951996.

Biographies

Svilen P. Simeonov graduated from Sofia University in 2004 and joined the Institute of Organic Chemistry with Centre of Phytochemistry, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, as a research fellow. In 2010 he moved to the University of Lisbon and received his Ph.D. in 2014 under the supervision of Prof. Carlos A. M. Afonso. Afterward, he returned to Sofia and currently holds an associate professor position at the Institute of Organic Chemistry with Centre of Phytochemistry, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. His research interests are mainly focused on green chemistry methodologies, flow chemistry, valorization of natural resources, and TM-catalyzed C–H functionalizations

Adolfo Fernández-Figueiras graduated with a degree in Chemistry in 2012 from the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain) and obtained his Ph.D. in December 2017 at the same university under the direction of Professor Vila. In 2020 he joined Professor Simeonov’s group, belonging to the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (Sofia, Bulgaria) as a postdoctoral researcher. His scientific interests are focused on the study of metal catalyzed C–H activation and isomerization reactions as well as on synthetic organometallic chemistry.

Martin Ravutsov studied chemistry at Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, where he obtained an M.Sc. in 2012. Afterwards he joined the Organic Synthesis and Stereochemistry group at the Institute of Organic Chemistry with the Centre of Phytochemistry, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, and obtained a Ph.D. in 2021 under the supervision of Prof. Vladimir Dimitrov. He currently holds a position as an Assistant Professor at the same institution. His research interests are mainly focused on organometallic chemistry and catalysis.

Author Contributions

○ A.F.-F. and M.A.R. have contributed equally. Conceptualization: S.P.S.; Drafting: A.F.-F. and M.A.R. Review and editing of the final manuscript S.P.S.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Rej S.; Das A.; Chatani N. Strategic evolution in transition metal-catalyzed directed C–H bond activation and future directions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 431, 213683. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree R. H.; Lei A. Introduction: CH Activation. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117 (13), 8481–8482. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambiagio C.; Schönbauer D.; Blieck R.; Dao-Huy T.; Pototschnig G.; Schaaf P.; Wiesinger T.; Zia M. F.; Wencel-Delord J.; Besset T.; Maes B. U. W.; Schnürch M. A comprehensive overview of directing groups applied in metal-catalysed C–H functionalisation chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47 (17), 6603–6743. 10.1039/C8CS00201K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bhattacharya T.; Pimparkar S.; Maiti D. Combining transition metals and transient directing groups for C–H functionalizations. RSC Adv. 2018, 8 (35), 19456–19464. 10.1039/C8RA03230K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhao Q.; Poisson T.; Pannecoucke X.; Besset T. The Transient Directing Group Strategy: A New Trend in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed C–H Bond Functionalization. Synthesis 2017, 49 (21), 4808–4826. 10.1055/s-0036-1590878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Liao G.; Zhang T.; Lin Z.-K.; Shi B.-F. Transition Metal-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Functionalization via Chiral Transient Directing Group Strategies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (45), 19773–19786. 10.1002/anie.202008437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gandeepan P.; Ackermann L. Transient Directing Groups for Transformative C–H Activation by Synergistic Metal Catalysis. Chem. 2018, 4 (2), 199–222. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M.; De Sarkar S. meta- and para-Selective C–H Functionalization using Transient Mediators and Noncovalent Templates. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7 (7), 1236–1255. 10.1002/ajoc.201800225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Dutta U.; Maiti S.; Pimparkar S.; Maiti S.; Gahan L. R.; Krenske E. H.; Lupton D. W.; Maiti D. Rhodium catalyzed template-assisted distal para-C–H olefination. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (31), 7426–7432. 10.1039/C9SC01824G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xu H.; Liu M.; Li L.-J.; Cao Y.-F.; Yu J.-Q.; Dai H.-X. Palladium-Catalyzed Remote meta-C–H Bond Deuteration of Arenes Using a Pyridine Template. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (12), 4887–4891. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li M.; Shang M.; Xu H.; Wang X.; Dai H.-X.; Yu J.-Q. Remote Para-C–H Acetoxylation of Electron-Deficient Arenes. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (2), 540–544. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Brochetta M.; Borsari T.; Bag S.; Jana S.; Maiti S.; Porta A.; Werz D. B.; Zanoni G.; Maiti D. Direct meta-C–H Perfluoroalkenylation of Arenes Enabled by a Cleavable Pyrimidine-Based Template. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25 (44), 10323–10327. 10.1002/chem.201902811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dey A.; Sinha S. K.; Achar T. K.; Maiti D. Accessing Remote meta- and para-C(sp2)–H Bonds with Covalently Attached Directing Groups. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (32), 10820–10843. 10.1002/anie.201812116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Haldar C.; Emdadul Hoque M.; Bisht R.; Chattopadhyay B. Concept of Ir-catalyzed CH bond activation/borylation by noncovalent interaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59 (14), 1269–1277. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.01.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kuninobu Y.; Torigoe T. Recent progress of transition metal-catalysed regioselective C–H transformations based on noncovalent interactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18 (22), 4126–4134. 10.1039/D0OB00703J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liao G.; Wu Y.-J.; Shi B.-F. Noncovalent Interaction in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Selective CH Activation. Acta Chim. Sinica 2020, 78 (4), 289–298. 10.6023/A20020027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Koshevoy I. O.; Krause M.; Klein A. Non-covalent intramolecular interactions through ligand-design promoting efficient photoluminescence from transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 405, 213094. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J. F.; Larsen M. A. Undirected, Homogeneous C–H Bond Functionalization: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2 (5), 281–292. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosen P. C.; Kallepalli V. A.; Chattopadhyay B.; Singleton D. A.; Maleczka R. E.; Smith M. R. Outer-Sphere Direction in Iridium C–H Borylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (28), 11350–11353. 10.1021/ja303443m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preshlock S. M.; Plattner D. L.; Maligres P. E.; Krska S. W.; Maleczka R. E.; Smith M. R. A Traceless Directing Group for C-H Borylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (49), 12915–12919. 10.1002/anie.201306511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht R.; Chattopadhyay B. Formal Ir-Catalyzed Ligand-Enabled Ortho and Meta Borylation of Aromatic Aldehydes via in Situ-Generated Imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (1), 84–87. 10.1021/jacs.5b11683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. L.; Kuninobu Y.; Kanai M. Lewis Acid–Base Interaction-Controlled ortho-Selective C–H Borylation of Aryl Sulfides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (6), 1495–1499. 10.1002/anie.201610041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.-L.; Kanai M.; Kuninobu Y. Iridium/Bipyridine-Catalyzed ortho-Selective C–H Borylation of Phenol and Aniline Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (21), 5944–5947. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay B.; Dannatt J. E.; Andujar-De Sanctis I. L.; Gore K. A.; Maleczka R. E.; Singleton D. A.; Smith M. R. Ir-Catalyzed ortho-Borylation of Phenols Directed by Substrate–Ligand Electrostatic Interactions: A Combined Experimental/in Silico Strategy for Optimizing Weak Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (23), 7864–7871. 10.1021/jacs.7b02232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S.-T.; Bheeter C. B.; Reek J. N. H. Hydrogen Bond Directed ortho-Selective C–H Borylation of Secondary Aromatic Amides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (37), 13039–13043. 10.1002/anie.201907366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuninobu Y.; Ida H.; Nishi M.; Kanai M. A meta-selective C–H borylation directed by a secondary interaction between ligand and substrate. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7 (9), 712–717. 10.1038/nchem.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. J.; Mihai M. T.; Phipps R. J. Ion Pair-Directed Regiocontrol in Transition-Metal Catalysis: A Meta-Selective C–H Borylation of Aromatic Quaternary Ammonium Salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (39), 12759–12762. 10.1021/jacs.6b08164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihai M. T.; Davis H. J.; Genov G. R.; Phipps R. J. Ion Pair-Directed C–H Activation on Flexible Ammonium Salts: meta-Selective Borylation of Quaternized Phenethylamines and Phenylpropylamines. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (5), 3764–3769. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.; Mihai M. T.; Stojalnikova V.; Phipps R. J. Ion-Pair-Directed Borylation of Aromatic Phosphonium Salts. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84 (20), 13124–13134. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. J.; Genov G. R.; Phipps R. J. meta-Selective C–H Borylation of Benzylamine-, Phenethylamine-, and Phenylpropylamine-Derived Amides Enabled by a Single Anionic Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (43), 13351–13355. 10.1002/anie.201708967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht R.; Hoque M. E.; Chattopadhyay B. Amide Effects in C–H Activation: Noncovalent Interactions with L-Shaped Ligand for meta Borylation of Aromatic Amides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (48), 15762–15766. 10.1002/anie.201809929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Uemura N.; Nakao Y. meta-Selective C–H Borylation of Benzamides and Pyridines by an Iridium–Lewis Acid Bifunctional Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (19), 7972–7979. 10.1021/jacs.9b03138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hu Y.; Wang C. Bimetallic C―H Activation in Homogeneous Catalysis. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2019, 35 (9), 913–922. 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201809036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li J.-F.; Luan Y.-X.; Ye M. Bimetallic anchoring catalysis for C-H and C-C activation. Sci. China Chem. 2021, 64 (11), 1923–1937. 10.1007/s11426-021-1068-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Semba K.; Nakao Y. para-Selective C–H Borylation of (Hetero)Arenes by Cooperative Iridium/Aluminum Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (17), 4853–4857. 10.1002/anie.201701238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque M. E.; Bisht R.; Haldar C.; Chattopadhyay B. Noncovalent Interactions in Ir-Catalyzed C–H Activation: L-Shaped Ligand for Para-Selective Borylation of Aromatic Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (23), 7745–7748. 10.1021/jacs.7b04490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihai M. T.; Williams B. D.; Phipps R. J. Para-Selective C–H Borylation of Common Arene Building Blocks Enabled by Ion-Pairing with a Bulky Countercation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (39), 15477–15482. 10.1021/jacs.9b07267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero Bastidas J. R.; Oleskey T. J.; Miller S. L.; Smith M. R.; Maleczka R. E. Para-Selective, Iridium-Catalyzed C–H Borylations of Sulfated Phenols, Benzyl Alcohols, and Anilines Directed by Ion-Pair Electrostatic Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (39), 15483–15487. 10.1021/jacs.9b08464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Tanaka K.; Yu J.-Q. Remote site-selective C–H activation directed by a catalytic bifunctional template. Nature 2017, 543 (7646), 538–542. 10.1038/nature21418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achar T. K.; Ramakrishna K.; Pal T.; Porey S.; Dolui P.; Biswas J. P.; Maiti D. Regiocontrolled Remote C–H Olefination of Small Heterocycles. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24 (68), 17906–17910. 10.1002/chem.201804351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna K.; Biswas J. P.; Jana S.; Achar T. K.; Porey S.; Maiti D. Coordination Assisted Distal C–H Alkylation of Fused Heterocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (39), 13808–13812. 10.1002/anie.201907544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Yan Y.; Zhang P.; Xu X.; Jin Z. Palladium-Catalyzed meta-Selective C–H Functionalization by Noncovalent H-Bonding Interaction. ACS Catal. 2021, 11 (16), 10460–10466. 10.1021/acscatal.1c02974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]