Abstract

Symptom endorsement after traumatic brain injury (TBI) is common acutely post-injury and is associated with other adverse outcomes. Prevalence of persistent symptoms has been debated, especially in mild TBI (mTBI). A cohort of participants ≥17 years with TBI (n = 2039), 257 orthopedic trauma controls (OTCs), and 300 friend controls (FCs) were enrolled in the TRACK-TBI study and evaluated at 2 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months post-injury using the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ). TBI participants had significantly higher symptom burden than OTCs or FCs at all times, with average scores more than double. TBI cases showed significant decreases in RPQ score between each evaluation (p < 0.001), decreasing ∼1.7 points per month between 2 weeks and 3 months and 0.2 points per month after that. More than 50% of the TBI sample, including >50% of each of the mild and moderate/severe TBI subsamples, continued to endorse three or more symptoms as worse than pre-injury through 12 months post-injury. A majority of TBI participants who endorsed a symptom at 3 months or later did so at the next evaluation as well. Contrary to reviews that report symptom resolution by 3 months post-injury among those with mTBI, this study of participants treated at level 1 trauma centers and having a computed tomography ordered found that persistent symptoms are common to at least a year after TBI. Additionally, although symptom endorsement was not specific to TBI given that they were also reported by OTC and FC participants, TBI participants endorsed over twice the symptom burden compared with the other groups.

Keywords: post-concussion symptoms, post-traumatic symptoms, TRACK-TBI, traumatic brain injuries

Introduction

The consequences of traumatic brain injury (TBI) are broad, often including objective signs of neurological dysfunction (such as hemiparesis, impaired cognitive functioning), functional status difficulties, decreased quality of life, and self-reported post-traumatic symptoms. Research on symptom endorsement post-TBI has been extensive, especially after mild TBI (mTBI), but controversies persist about the prevalence and specificity of reported symptoms.1 Few dispute that symptoms are common through 1 month after mTBI and may be of much longer duration in those with moderate or severe injuries (msTBI).2–5

More controversial is whether and at what prevalence symptoms continue to be reported in those with mTBI at ≥3 months post-injury. The results of the World Health Organization task force on mTBI concluded that most studies report recovery from symptoms by 3–12 months post-injury,6 further supported by a systematic review.7 However, included studies had small sample sizes with high loss-to-follow-up rates potentially biasing results,8–11 and time gaps between evaluations may have prevented careful examination of patterns of endorsement over time. Recent large-scale studies found lingering mTBI symptoms in around half of cases at 1 year post-mTBI.12,13

Study of individual symptoms has largely been restricted to tabular report of percent endorsement over time.2,12,14 Some studies have suggested that symptoms of physical functioning, such as headaches and fatigue, are predominant within 3 months of mTBI15,16 whereas cognitive symptoms predominate later.16,17 Most of these studies do not allow assessment of persistence of symptoms within a person, and the few existing analyses report inconsistent findings.18–21

Symptoms experienced by those who sustain a TBI are not specific to TBI,1,22,23 but occur at significantly higher rates compared with non-brain-trauma control or community control groups early and late after injury.2,17,24–27 For example, 53% of participants with TBI reported three or more symptoms versus 24% of trauma controls at 1 year post-injury, and the most common symptoms reported by both groups included fatigue, irritability, and headache.2

This analysis examined the prevalence and persistence of symptom endorsement over the first year after TBI in comparison to two control groups, orthopedic trauma controls (OTCs) and healthy friend/family controls (FCs). We hypothesized that symptoms would be reported by over half of TBI participants throughout the year after injury, symptom burden would be higher among those with TBI than among OTCs and FCs, symptom endorsement would decrease most in the first 3 months, and cognitive symptoms would be the most prevalent at 1 year.

Methods

Participants

The Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI (TRACK-TBI) prospective cohort study enrolled 2697 participants with TBI at 18 U.S. level 1 trauma centers between February 26, 2014 and July 3, 2018. Participants were evaluated at 2 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months post-injury. All TBI participants sustained a TBI <24 h before enrollment and received an acute head computed tomography (CT) for clinical care. TRACK-TBI also enrolled 299 OTCs who sustained an orthopedic injury with Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) ≤4 and no alteration of consciousness or post-traumatic amnesia from the same sites between January 26, 2016 and July 27, 2018; 300 FCs, friends or family members of TBI participants with no traumatic injury within the year preceding enrollment, were enrolled from May 26, 2017 to September 25, 2019. The current analysis included participants ≥17 years of age who completed the symptom measure at least one time. Participants too impaired to complete the full TRACK-TBI outcome battery had an abbreviated assessment that did not assess symptoms. For more detailed information about inclusion and exclusion criteria, see McCrea and colleagues.28 The institutional review boards of each participating site approved this study.

Primary outcome measure

The Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ)29 consists of 16 symptoms that participants rate to indicate severity of the symptom experienced in the past 7 days compared to before the injury. The instructions for the FCs were modified by removing any reference to TBI or accident, and they were asked to compare their symptoms in the past 7 days to what they had experienced during the equivalent time before the assessment, for example relating back 3 months before the 3-month assessment. The RPQ was administered at each assessment time point. Symptoms were rated as not experienced at all (0), no more of a problem compared to before the injury (1), a mild problem (2), a moderate problem (3), or a severe problem (4). A symptom was considered endorsed if the participant rated it from 2 to 4, (i.e., either new or more of a problem than pre-injury). RPQ scores range from 0 to 64. To calculate the total symptom score, items rated 1 were recoded to 0 before summing across all symptoms.

Statistical analysis

RPQ total score and number of symptoms endorsed at each time point, endorsement of each symptom, and persistence of each symptom over adjacent assessments are presented descriptively. Percent persistence was defined as the number of participants endorsing a symptom at both times divided by the number who endorsed it at the earlier assessment. We used linear mixed models, including group or TBI subgroup, time (categorical), and their interaction, to formally evaluate the pattern of recovery and its consistency across groups or TBI subgroups. We defined mTBI as Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)30 13–15 and msTBI as GCS 3–12. If interactions were non-significant, we ran the mixed model with only main effects. To examine whether results were unduly influenced by the skew of the RPQ scores, we performed sensitivity analyses on ranks of the score within the entire sample combined over group and time. Threshold for significance, adjusted for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate for each linear model and rank-based model separately,31 was p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 19; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

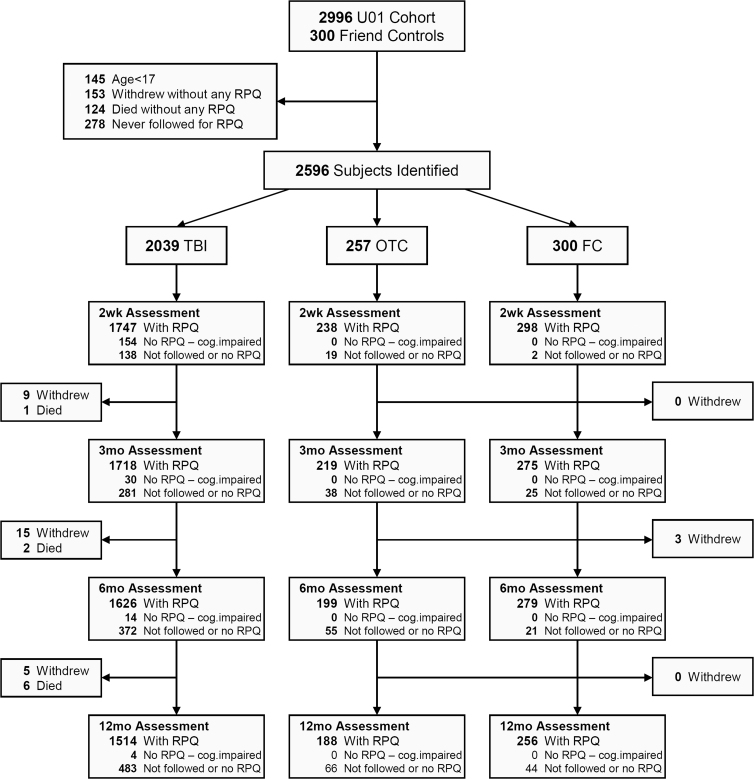

The number of participants with a completed RPQ at each time point is shown in Figure 1. Demographic and injury characteristics of the groups are provided in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Participant flow. No RPQ—cog.impaired=RPQ was not done because the participant was administered an abbreviated battery because of cognitive impairment. FC, friend control group; OTC, orthopedic trauma control group; RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; TBI, traumatic brain injury group.

Table 1.

Demographics and Injury Characteristics by Groupa

| TBI | OTC | FC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2039 | 257 | 300 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.20 (17) | 40.07 (15) | 37.59 (15) |

| 17–39 (%) | 1124 (55) | 141 (55) | 188 (63) |

| 40–64 | 698 (34) | 98 (38) | 89 (30) |

| 65+ | 217 (11) | 18 (7) | 23 (7) |

| Male (%) | 1389 (68) | 169 (66) | 191 (64) |

| Education | |||

| Did not graduate HS | 237 (12) | 23 (9) | 19 (6) |

| HS/GED | 531 (27) | 53 (21) | 59 (20) |

| Some college | 643 (32) | 91 (36) | 115 (39) |

| Four-year college degree | 580 (29) | 88 (34) | 105 (35) |

| Race | |||

| White (%) | 1573 (78) | 196 (78) | 227 (76) |

| Black | 335 (16) | 43 (17) | 45 (15) |

| Other | 121 (6) | 14 (5) | 26 (9) |

| TBI severity | |||

| GCS 3–8 (%) | 194 (10) | ||

| GCS 9–12 | 79 (4) | ||

| GCS 13–15, CT positive | 601 (30) | ||

| GCS 13–15, CT negative | 1080 (55) | ||

| Other system injury severity | |||

| AIS subneck ≥3 (%) | 371 (18) | 56 (22) |

Based on cases in each group who answered at least one symptom in at least one time period.

SD, standard deviation; TBI, traumatic brain injury group; OTC, orthopedic trauma control group; FC, friend control group; HS, high school, GED, General Educational Development; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; CT, computed tomography; AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale.

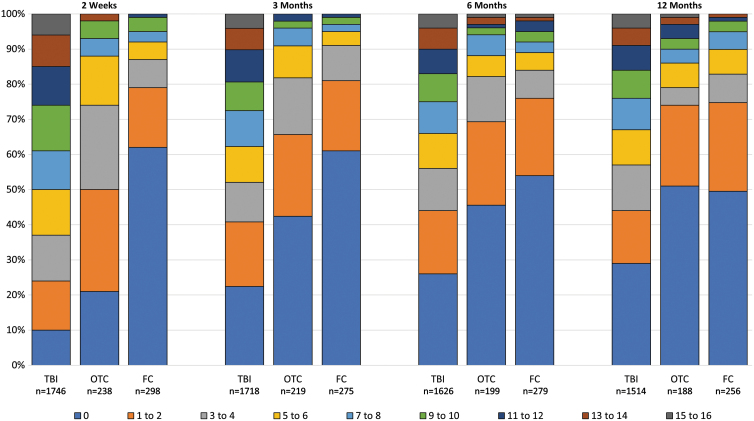

Symptom prevalence by group

Stacked bars show the percentage of cases in each group with 0–16 symptoms endorsed at any severity level at each time (Fig. 2). The pattern of symptom endorsement was similar when symptoms were restricted to those causing moderate or severe or only severe problems (Supplementary Fig. S1A,B) TBI participants reported significantly higher symptom burden at each time (2 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months; means, 18.42, 14.15, 13.04, and 12.48) than OTCs (7.74, 5.72, 5.37, and 5.59) or FCs (3.84, 3.27, 4.72, and 4.98; Tables 2 and 3 and Supplementary Table S1) OTCs endorsed significantly higher burden than FCs at 2 weeks (7.74 vs. 3.84).

FIG. 2.

Number of symptoms endorsed at any severity by group and time. FC, friend control group; OTC, orthopedic trauma control group; TBI, traumatic brain injury group. Color image is available online.

Table 2.

RPQ Total Score and Number of Symptoms Endorsed by Time and Group

| TBI | OTC | FC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | |||

| n | 1746 | 238 | 298 |

| Total score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18.42 (14.76) | 7.74 (8.47) | 3.84 (7.53) |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (6, 28) | 6 (2, 11) | 0 (0, 4) |

| No. endorsed | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.86 (4.7) | 3.12 (2.96) | 1.58 (2.89) |

| Median (IQR) | 7 (3, 11) | 2.5 (1, 5) | 0 (0, 2) |

| 3 months | |||

| n | 1718 | 219 | 275 |

| Total score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.15 (14.53) | 5.72 (8.17) | 3.27 (6.45) |

| Median (IQR) | 9 (2, 24) | 2 (0, 8) | 0 (0, 4) |

| No. endorsed | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.29 (4.86) | 2.28 (2.96) | 1.35 (2.46) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (1, 9) | 1 (0, 3) | 0 (0, 2) |

| 6 months | |||

| N | 1626 | 199 | 279 |

| Total score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.04 (14.39) | 5.37 (8.83) | 4.72 (8.44) |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (0, 21) | 2 (0, 7) | 0 (0, 5) |

| No. endorsed | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.93 (4.82) | 2.19 (3.25) | 1.99 (3.33) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (0, 9) | 1 (0, 3) | 0 (0, 2) |

| 12 months | |||

| n | 1514 | 188 | 256 |

| Total score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.48 (14.06) | 5.59 (9.89) | 4.98 (8.22) |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (0, 20) | 0 (0, 6) | 2 (0, 6) |

| No. endorsed | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.7 (4.7) | 2.19 (3.52) | 2.05 (3.13) |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (0, 8) | 0 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) |

RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; TBI, traumatic brain injury group; OTC, orthopedic trauma control group; FC, friend control group.

Table 3.

Comparison of RPQ Scores by Group and Time

| Comparison | Raw mean diff. | Modeled estimates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear |

Ranked |

||||||

| B | 95% CI | p | p MC | p | p MC | ||

| TBI vs. OTC at 2wk | 10.68 | 10.75 | (8.98, 12.51) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. OTC at 3mo | 8.43 | 8.54 | (6.74, 10.34) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. OTC at 6mo | 7.67 | 7.93 | (6.09, 9.78) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. OTC at 1yr | 6.89 | 6.59 | (4.72, 8.45) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. FC at 2wk | 14.58 | 14.95 | (13.33, 16.58) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. FC at 3mo | 10.88 | 10.76 | (9.11, 12.41) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. FC at 6mo | 8.32 | 8.29 | (6.64, 9.95) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TBI vs. FC at 1yr | 7.50 | 7.48 | (5.80, 9.16) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OTC vs. FC at 2wk | 3.90 | 4.21 | (1.96, 6.45) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OTC vs. FC at 3mo | 2.45 | 2.23 | (−0.07, 4.52) | 0.057 | 0.081 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| OTC vs. FC at 6mo | 0.65 | 0.36 | (−1.96, 2.68) | 0.761 | 0.804 | 0.609 | 0.652 |

| OTC vs. FC at 1yr | 0.61 | 0.89 | (−1.46, 3.25) | 0.457 | 0.549 | 0.747 | 0.772 |

| 3mo vs. 2wk for TBI | –4.28 | –4.59 | (−5.10, −4.08) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 2wk for TBI | –5.38 | –5.71 | (−6.23, −5.19) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 2wk for TBI | –5.94 | –6.35 | (−6.89, −5.82) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 3mo for TBI | –1.10 | –1.12 | (−1.64, −0.60) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 3mo for TBI | –1.66 | –1.76 | (−2.29, −1.23) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 6mo for TBI | –0.56 | –0.64 | (−1.18, −0.11) | 0.018 | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.031 |

| 3mo vs. 2wk for OTC | –2.02 | –2.38 | (−3.79, −0.98) | 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 2wk for OTC | –2.37 | –2.90 | (−4.34, −1.45) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 2wk for OTC | –2.15 | –2.19 | (−3.67, −0.72) | 0.004 | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 3mo for OTC | –0.35 | –0.51 | (−1.98, 0.95) | 0.491 | 0.566 | 0.139 | 0.174 |

| 1yr vs. 3mo for OTC | –0.13 | 0.19 | (−1.30, 1.68) | 0.804 | 0.804 | 0.233 | 0.279 |

| 1yr vs. 6mo for OTC | 0.22 | 0.70 | (−0.81, 2.22) | 0.362 | 0.452 | 0.800 | 0.800 |

| 3mo vs. 2wk for FC | –0.57 | –0.40 | (−1.63, 0.83) | 0.524 | 0.582 | 0.548 | 0.609 |

| 6mo vs. 2wk for FC | 0.88 | 0.95 | (−0.27, 2.18) | 0.128 | 0.166 | 0.034 | 0.045 |

| 1yr vs. 2wk for FC | 1.13 | 1.12 | (−0.14, 2.38) | 0.081 | 0.110 | 0.007 | 0.011 |

| 6mo vs. 3mo for FC | 1.45 | 1.35 | (0.10, 2.61) | 0.035 | 0.053 | 0.008 | 0.011 |

| 1yr vs. 3mo for FC | 1.71 | 1.52 | (0.23, 2.81) | 0.021 | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| 1yr vs. 6mo for FC | 0.26 | 0.17 | (−1.11, 1.45) | 0.794 | 0.804 | 0.535 | 0.609 |

pMC = p value adjusted for multiple comparisons (m = 30) using a false discovery rate.

RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; CI, confidence interval; TBI, traumatic brain injury group; OTC, orthopedic trauma control group; FC, friend control group.

TBI cases showed significant decreases in RPQ total score between each pair of assessment times. RPQ score in the TBI group decreased by an estimated 1.7 points per month between 2 weeks and 3 months and 0.2 points per month between 3 and 12 months. OTCs also had significantly lower RPQ scores at 3 months than at 2 weeks (estimated 0.8 points per month decrease), but changes after 3 months were non-significant (Table 3). Findings were similar for the linear and ranked analyses, except that the ranked analysis indicated that OTCs reported a significantly higher symptom burden than FCs at 3 months, whereas the trend was non-significant in the linear analysis. Not all persons had decreasing symptoms, with 12–15% of participants reporting a new or more severely problematic symptom at each time.

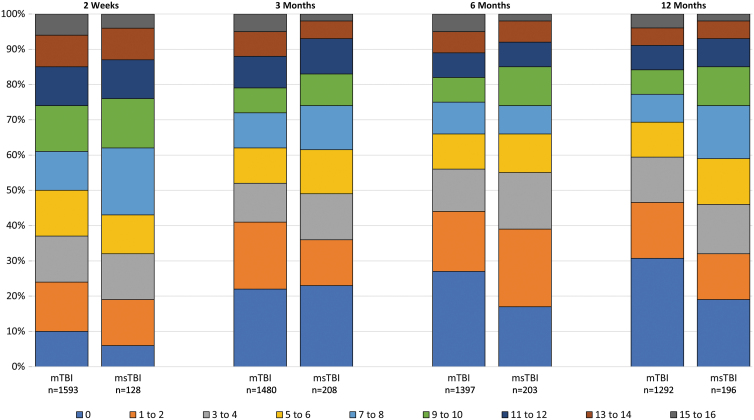

Symptom prevalence by traumatic brain injury severity subgroup

Symptom endorsement was similar among the mTBI and msTBI subgroups during the first 6 months (Tables 4 and 5; Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S2). Symptom burden in both groups decreased significantly between 2 weeks and 3 months. The burden continued to decrease significantly in the mTBI subgroup, but more slowly over time. With the smaller sample size, the pattern at later times in the msTBI group is less clear. By 12 month, the msTBI subgroup was reporting a score ∼2 points higher than the mTBI group, which is non-significant by the linear analysis, but significant by the ranked sensitivity analysis.

Table 4.

RPQ Total Score and Number of Symptoms Endorsed by Time and TBI Severity Subgroup

| Mild TBI | Moderate/severe TBI | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | ||

| n | 1593 | 128 |

| Total score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 18.4 (14.9) | 18.4 (13.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (6, 28) | 16 (7, 28) |

| No. endorsed | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (4.8) | 7.0 (4.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3, 11) | 7 (3, 10) |

| 3 months | ||

| n | 1480 | 208 |

| Total score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 14.2 (14.8) | 13.6 (12.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 9 (2, 24) | 11 (2, 22.75) |

| No. endorsed | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (4.9) | 5.2 (4.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (1, 9) | 5 (1, 9) |

| 6 months | ||

| n | 1397 | 203 |

| Total score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 12.9 (14.6) | 13.0 (12.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (0, 20.50) | 9 (3, 21) |

| No. endorsed | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (4.9) | 4.9 (4.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (0, 8) | 4 (1, 9) |

| 12 months | ||

| n | 1292 | 196 |

| Total score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 12.2 (14.2) | 14.4 (12.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (0, 20) | 11 (3.25, 22) |

| No. endorsed | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (4.8) | 5.5 (4.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (0, 8) | 5 (1.25, 9) |

RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; TBI, traumatic brain injury; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 5.

Comparison of RPQ Scores by TBI Severity Subgroup and Time

| Comparison | Raw mean diff. | Modeled estimates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear |

Ranked |

||||||

| B | 95% CI | p | p MC | p | p MC | ||

| mTBI vs. msTBI at 2wk | 0.03 | –1.35 | (−3.55, 0.86) | 0.232 | 0.286 | 0.022 | 0.032 |

| mTBI vs. msTBI at 3mo | 0.59 | 0.08 | (−1.89, 2.05) | 0.935 | 0.976 | 0.431 | 0.493 |

| mTBI vs. msTBI at 6mo | –0.07 | 0.32 | (−1.66, 2.31) | 0.750 | 0.857 | 0.519 | 0.553 |

| mTBI vs. msTBI at 1yr | –2.20 | –1.89 | (−3.89, 0.11) | 0.065 | 0.103 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| 3mo vs. 2wk for mTBI | –4.24 | –4.48 | (−5.06, −3.91) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 2wk for mTBI | –5.48 | –5.63 | (−6.21, −5.04) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 2wk for mTBI | –6.25 | –6.48 | (−7.08, −5.88) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 3mo for mTBI | –1.24 | –1.14 | (−1.74, −0.55) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 3mo for mTBI | –2.02 | –2.00 | (−2.60, −1.39) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 6mo for mTBI | –0.77 | –0.85 | (−1.47, −0.24) | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.009 |

| 3mo vs. 2wk for msTBI | –4.79 | –5.91 | (−7.80, −4.02) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 2wk for msTBI | –5.38 | –7.29 | (−9.22, −5.37) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 1yr vs. 2wk for msTBI | –4.02 | –5.94 | (−7.90, −3.97) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6mo vs. 3mo for msTBI | –0.59 | –1.38 | (−2.98, 0.22) | 0.090 | 0.131 | 0.073 | 0.098 |

| 1yr vs. 3mo for msTBI | 0.77 | –0.03 | (−1.68, 1.63) | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| 1yr vs. 6mo for msTBI | 1.36 | 1.36 | (−0.27, 2.99) | 0.103 | 0.137 | 0.085 | 0.104 |

Statistical significance by mixed-effects linear/rank regression.

pMC = p value adjusted for multiple comparisons (m = 16) using a false discovery rate.

RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; TBI, traumatic brain injury; mTBI, mild TBI; msTBI, moderate or severe TBI.

FIG. 3.

Number of symptoms endorsed at any severity by traumatic brain injury (TBI) severity subgroup and time. mTBI, mild TBI (admission Glasgow Coma Scale score 13–15); msTBI, moderate or severe TBI (admission Glasgow Coma Scale score 3–12). Color image is available online.

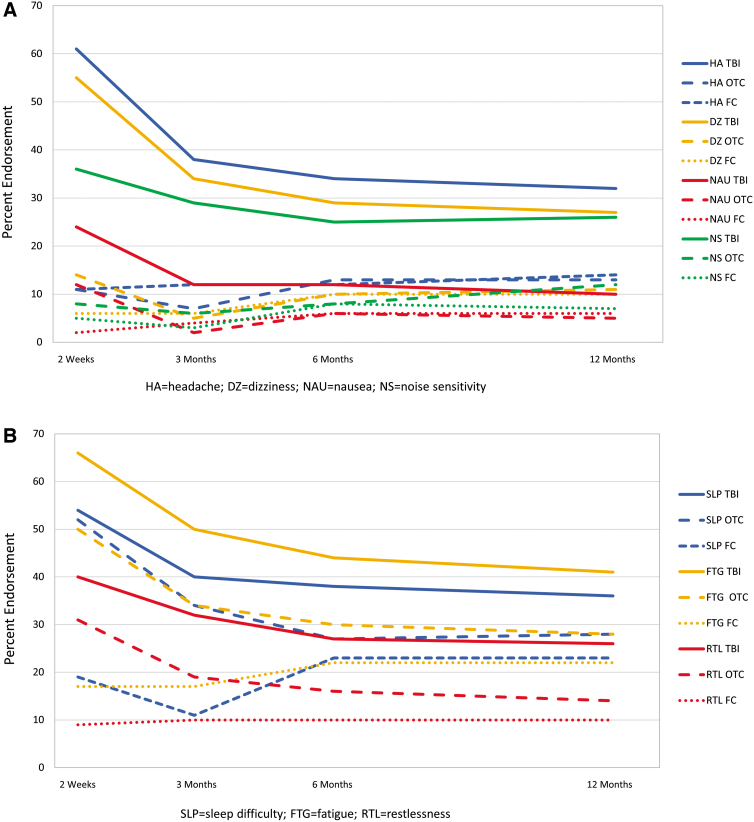

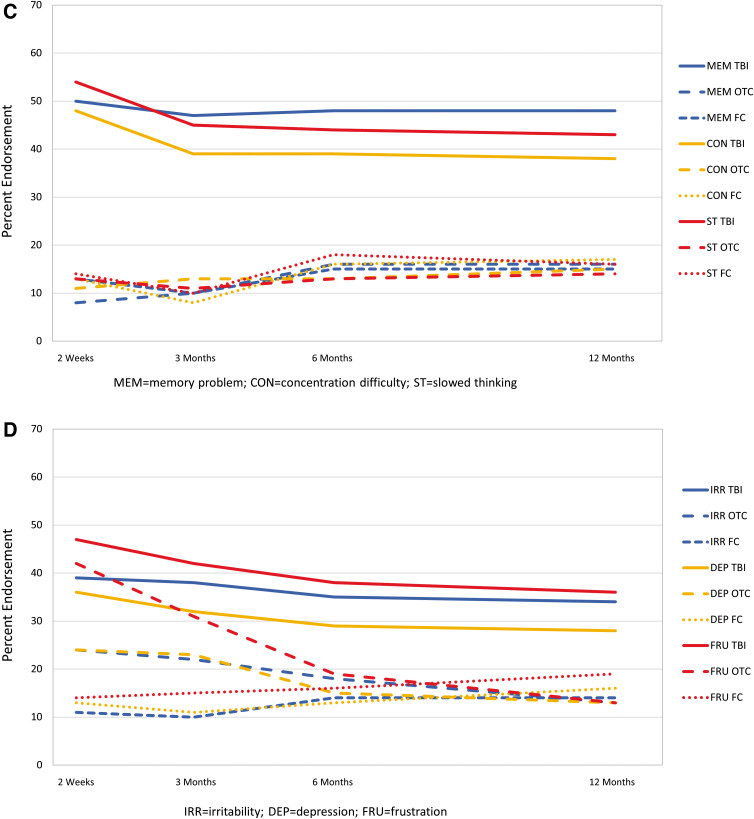

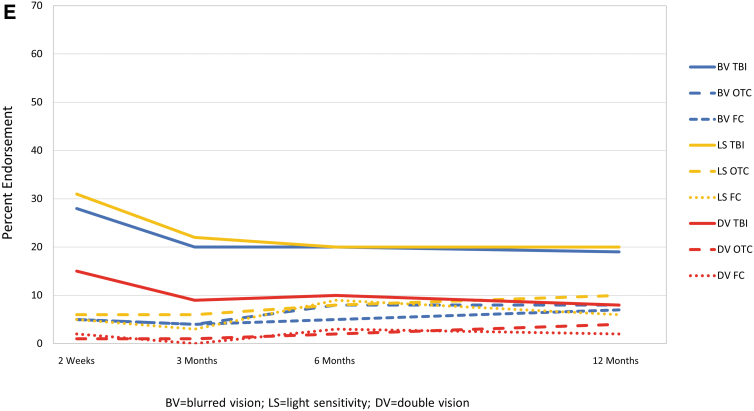

Individual symptom prevalence

For each symptom and time, endorsement rate was highest for those with TBI (Fig. 4). Generally, for the TBI and OTC groups, symptoms showed the highest endorsement at 2 weeks with a substantial decrease by 3 months and less recovery from 3 to 12 months post-injury. Endorsement of cognitive symptoms by group showed little change over time, and each cognitive symptom was endorsed by at least 35% of those with TBI and <20% of those in the OTC and FC groups at each time.

FIG. 4.

Percentage of participants endorsing individual symptoms at any severity level by group and time. (A) Somatic symptoms. (B) Sleep difficulty, fatigue, and restlessness. (C) Cognitive symptoms. (D) Emotional symptoms. (E) Visual symptoms. FC, friend control group; OTC, orthopedic trauma control group; TBI, traumatic brain injury group. Color image is available online.

Symptom persistence

The majority of symptoms endorsed by TBI participants at any given time were also endorsed at the next visit (50–66% of symptoms endorsed at 2 weeks endorsed at 3 months; 60–79% of symptoms endorsed at 3 and 6 months endorsed at 6 and 12 months, respectively). Memory problems and taking longer to think had the highest persistence across each interval, with >60% persistence from 2 weeks to 3 months and >70% for the later intervals (Table 6). Poor concentration, fatigue, headache, sleep disturbance, and irritability were endorsed frequently (35–51% at 3 or 6 months), with around two thirds of TBI participants endorsing the symptoms at 3 or 6 months reporting it again at the next assessment (66–71%). Vision problems and nausea were least commonly reported and the least persistent of symptoms. The pattern of problems with high persistence was similar in the TBI severity subgroups (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 6.

Symptom Prevalence at Each Time and Persistence at the Next Assessment (TBI Group)

| 2 weeks n = 1503 Endorsed n (%a) [95% CI] |

3 months Persisted n %b (95% CI) |

3 months n = 1476 Endorsed n (%a) [95% CI] |

6 months Persisted n %b (95% CI) |

6 months n = 1377 Endorsed n (%a) [95% CI] |

12 months Persisted n %b (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headaches | 919 (61) [59,64] |

472 51 (48,55) |

560 (38) [35,40] |

373 67 (63,71) |

479 (35) [32,37] |

322 67 (63,71) |

| Dizziness | 836 (56) [53,58] |

386 46 (43,50) |

500 (34) [31,36] |

295 59 (55,63) |

411 (30) [27,32] |

244 59 (54,64) |

| Nausea | 360 (24) [22,26] |

97 27 (22,32) |

169 (11) [10,13] |

89 53 (45,60) |

161 (12) [10,14] |

60 37 (30,45) |

| Noise sensitivity | 543 (36) [34,39] |

301 55 (51,60) |

442 (30) [28,32] |

256 58 (53,63) |

334 (24) [22,27] |

220 66 (61,71) |

| Sleep disturbance | 818 (54) [52,57] |

436 53 (50,57) |

586 (40) [37,42] |

391 67 (63,71) |

523 (38) [35,41] |

352 67 (63,71) |

| Fatigue | 1008 (67) [65,69] |

617 61 (58,64) |

748 (51) [48,53] |

492 66 (62,69) |

595 (43) [41,46] |

408 69 (65,72) |

| Irritability | 598 (40) [37,42] |

384 64 (60,68) |

559 (38) [35,40] |

381 68 (64,72) |

488 (35) [33,38] |

336 69 (65,73) |

| Depressed | 543 (36) [34,39] |

321 59 (55,63) |

472 (32) [30,34] |

293 62 (58,66) |

400 (29) [27,32] |

245 61 (56,66) |

| Frustrated | 716 (48) [45,50] |

440 61 (58,65) |

625 (42) [40,45] |

405 65 (61,69) |

526 (38) [36,41] |

339 64 (60,69) |

| Poor memory | 774 (51) [49,54] |

513 66 (63,70) |

703 (48) [45,50] |

552 79 (75,82) |

671 (49) [46,51] |

528 79 (75,82) |

| Poor concentration | 730 (49) [46,51] |

427 58 (55,62) |

581 (39) [37,42] |

410 71 (67,74) |

546 (40) [37,42] |

385 71 (66,74) |

| Longer to think | 839 (56) [53,58] |

529 63 (60,66) |

665 (45) [42,48] |

501 75 (72,79) |

615 (45) [42,47] |

450 73 [69,77] |

| Blurred vision | 426 (28) [26,31] |

185 43 [39,48] |

287 (19) [17,22] |

187 65 (59,71) |

282 (20) [18,23] |

166 59 (53,65) |

| Light sensitivity | 479 (32) [30,34] |

218 46 (41,50) |

324 (22) [20,24] |

176 54 (49,60) |

280 (20) [18,23] |

166 59 (53,65) |

| Double vision | 220 (15) [13,17] |

66 30 (24,37) |

129 (9) [7,10] |

55 43 (34,52) |

138 (10) [8,12] |

63 46 (37,54) |

| Restlessness | 614 (41) [38,43] |

324 53 (49,57) |

468 (32) [29,34] |

270 58 (53,62) |

362 (26) [24,29] |

226 62 (57,67) |

The n in the label for the earlier time is the number of participants with TBI who did the RPQ at both times. The persisted n is the number who endorsed that symptom both times, and the persisted percent is the percentage of those endorsing the symptom at the earlier time who also endorsed it at the later time. For example, for 2 weeks (2w) and 3 months (3m), 919 of 1503 = 61% of those with assessments at both times endorsed headache at 2w, and 472 of those 919 endorsed headache again at 3m (472 of 919 = 51%).

A symptom was considered endorsed if rated as mild (2), moderate (3), or severe (4).

A symptom was considered persisting if it was endorsed at the present assessment and the one immediately preceding the present.

TBI, traumatic brain injury; CI, confidence interval; RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, prevalence of symptoms is high over the first year after injury in those with TBI. At each time point, over two thirds of participants with TBI endorse at least one symptom as new or worsened compared with pre-injury: 90% at 2 weeks; 78% at 3 months; 74% at 6 months; and 71% at 12 months. Mean and median RPQ symptom scores for those with TBI were more than double that for OTCs and FCs at each time. Symptoms decreased steadily, on average, among those with TBI, at ∼1.7 RPQ points per month in the first 3 months, but then only 0.2 points per month for the rest of the year. OTCs also had a significant decrease in the first 3 months of around half the decrease noted among those with TBI, but no significant decrease thereafter.

Symptoms were reported consistently at adjacent time periods. That is, the majority of TBI participants who endorsd a symptom (other than nausea and some visual symptoms) at one time point reported it at the next assessment. The period from 2 weeks to 3 months appears the least consistent, with 27–66% of those endorsing a symptom at 2 weeks endorsing it at 3 months whereas later adjacent periods show most symptom persistence in the 60–75% range. Symptom reporting in the acute phase post-injury may be subject to more variability because of early resolution of some symptoms, discontinuation of sedating medications, and/or lack of early experience with symptom impact on daily functioning. Also, as hypothesized, cognitive symptoms were the most persistent (e.g., 71–79% at 6 and 12 months), although headache, fatigue, and irritability were almost as persistent (66–69%).

TRACK-TBI is one of the few studies that allows comparison of symptom endorsement to OTCs and FCs with no recent trauma. Symptoms are often criticized as an outcome measure for TBI because they are not specific to TBI.1,22,23 Whereas our results show some symptom endorsement by OTCs and FCs, our results also show that persons with TBI report more symptoms than uninjured persons and those with orthopedic injuries. Even at 2 weeks post-injury, those with TBI endorsed over twice the number of symptoms as OTCs. Later, and for all time points for FCs, both the mean number of symptoms and mean score are ∼2.5 times higher in those with TBI. Although OTCs endorsed a substantial number of symptoms compared to FCs at 2 weeks, by 3–6 months after injury, the overall symptom burden and rates of endorsement of each symptom were similar for OTCs and FCs. Theadom and colleagues12 found similar rates of headache endorsement on the RPQ in those with TBI relative to rates reported in a general population survey, suggesting that headaches may not be specifically a result of TBI.

There are, however, important differences between the RPQ and the general symptom inventory referenced by Theadom and colleagues. The RPQ asks respondents to report new symptoms or symptoms that have worsened since the injury, whereas the general survey referenced by Theadom and colleagues only asked about the presence of headaches. In this study, where participants without TBI compared current headaches with those experienced before their orthopedic injury or for FCs, preceding an equivalent time period before the assessment, we show that headaches are more than twice as common in those with TBI. Our findings are consistent in pattern with Skandsen and colleagues,27 who used a different instrument and found that 21% of mTBI cases, 8% of trauma controls, and 1% of healthy controls endorsed a high symptom burden at 3 months after injury. Accordingly, although symptoms may not be specific to TBI per se, their frequency and magnitude clearly differentiate patients with TBI from those with orthopedic injuries and from healthy, uninjured persons. However, this does not mean that symptoms can be used for differential diagnosis of individual patients.

Past research indicates that symptom prevalence post-TBI is varied and depends on multiple factors, including patient characteristics and time from injury. Most large studies indicate higher prevalence in the acute phase post-injury, followed by improvement.2,12,14 The results of our study are in agreement with past work, with the highest level of endorsement at 2 weeks, decreasing by 3 months, and with little additional improvement thereafter. We found that >70% of the TBI sample endorsed one or more symptoms at 1 year that caused new problems or worsened pre-injury ones.

Our results also support some reports that physical symptoms (e.g., headache, fatigue, and dizziness) prevail early15,16 and cognitive symptoms predominate (relative to other symptoms) later.16,17 In particular, physical symptoms decline more markedly over time, whereas cognitive symptoms are more constant over time and become the most prevalent type of complaint by 3–6 months post-injury. Emotional symptoms (irritability, frustration, and depression) also are more constant over time, although not as frequently endorsed as those in the cognitive domain. Visual symptoms and nausea are infrequently endorsed at all times. Providing patients with information about the type of symptom likely to improve, the ones that remain stable over time, and those that are reported with low frequency may be helpful when discussing prognosis, planning treatment, or designing clinical trials.

Several reviews have reported that most symptoms resolve by 3 months after an mTBI.6,7 Studies that formed the basis for these reviews, however, were small or had other methodological problems such as high dropout rates. Our findings are more consistent with those of Theadom and colleagues,12 who found that 47.9% of persons with mTBI reported at least four new or worsened symptoms at a year post-injury; we found that 42% of those with mTBI reported at least 4 symptoms at 12 months. Our analyses expand on the report by Nelson and colleagues,13 based on a subset of the TRACK-TBl sample used here, which found an average RPQ score of 12.5 a year after mTBI, significantly higher than for OTCs. This is important because past publications stating that symptoms usually resolve by 3 months after mild TBI may lead clinicians to discount later symptom complaints. Yet, we found that, by 3 months post-injury, the majority of participants with TBI who report a symptom worse than pre-injury will do so at the next adjacent time period, and over half of those with mTBI report three or more symptoms at a year after injury compared to around one quarter of those with orthopedic injuries or no injuries.

Endorsement of symptoms (at all levels of TBI severity) is associated with worse functional status32–39 and lower levels of community participation.17,40 These associations highlight the importance of developing targeted treatments aimed at reducing symptom burden. Despite the widespread problems associated with symptom endorsement, medical follow-up after mTBI is low and around half of those with mTBI reporting three or more moderate-to-severe symptoms at 3 months indicate that they had not seen a medical practitioner since initial discharge.41

This study has several strengths. TRACK-TBI is a longitudinal study that recruited almost 2700 TBI cases from 18 level 1 trauma centers in the United States and included both OTCs and FCs. Follow-ups occurred at four times across the year post-injury, allowing pattern of recovery to be examined without large gaps between observations.

The study also has limitations. The mTBI participants enrolled in the study may be more severely injured than other mTBI samples because they presented to a level 1 trauma center and required an acute head CT for clinical care. There may be retrospective recall bias, so-called good-old-days bias, which could change in unpredictable ways across subjects or groups as time post-injury grows, but it is not currently possible to assess and correct for such bias. The number of OTCs and FCs is modest. Participants with severe cognitive limitations at an assessment were not asked to report symptoms at that point. Although we know the number of persons who report symptoms at adjacent assessments, we do not know whether they experienced the symptom for the entire time between those assessments. Participants were not asked whether they attributed their symptoms to their TBI, their peripheral injuries, or both. No data were collected on treatments received.

Conclusion

Persistent symptoms were common after TBI of all severities in those who were seen in a U.S. level 1 trauma center and who received a head CT as part of clinical care; 50% reported three or more symptoms at a year after their injury, and >70% reported at least one problematic symptom. Almost one quarter of participants report at least one symptom causing severe problems at a point in time from 2 weeks to 6 months post-injury, and the majority report a new or worse symptom persisting into the adjacent time period. Clinicians should inquire about symptoms in patients who have had a TBI, reassure them that experiencing symptoms is common, and direct them to seek treatment for symptoms that are disrupting their lives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The TRACK-TBI Investigators: Neeraj Badjatia, MD, University of Maryland; Yelena Bodien, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital; Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, University of Pennsylvania; Ann-Christine Duhaime, MD, MassGeneral Hospital for Children; V. Ramana Feeser, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University; Adam R. Ferguson, PhD, University of California, San Francisco; Brandon Foreman, MD, University of Cincinnati; Etienne Gaudette, PhD, University of Toronto; Shankar Gopinath, MD, Baylor College of Medicine; Frederick K. Korley, MD, PhD, University of Michigan; Christopher Madden, MD, UT Southwestern; Pratik Mukherjee, MD, PhD, University of California, San Francisco; Laura B. Ngwenya, MD, PhD, University of Cincinnati; David Okonkwo, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; Ava Puccio, PhD, University of Pittsburgh; Claudia Robertson, MD, Baylor College of Medicine; Jonathan Rosand, MD, MSc, Massachusetts General Hospital; David Schnyer, PhD, UT Austin; Mary Vassar, RN, MS, University of California, San Francisco; John K. Yue, MD, University of California, San Francisco; Ross Zafonte, DO, Harvard Medical School.

Contributor Information

the TRACK-TBI Investigators:

Neeraj Badjatia, Yelena Bodien, Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, Ann-Christine Duhaime, V. Ramana Feeser, Adam R. Ferguson, Brandon Foreman, Etienne Gaudette, Shankar Gopinath, Frederick K. Korley, Christopher Madden, Pratik Mukherjee, Laura B. Ngwenya, David Okonkwo, Ava Puccio, Claudia Robertson, Jonathan Rosand, David Schnyer, Mary Vassar, John K. Yue, and Ross Zafonte

Collaborators: the TRACK-TBI Investigators

Funding Information

This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NINDS (Grant UO1-NS086090) and DoD (Grant W81XWH-14-2-0176).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Polinder, S., Cnossen, M.C., Real, R.G.L., Covic, A., Gorbunova, A., Voormolen, D.C., Master, C.L., Haagsma, J.A., Diaz-Arrastia, R., and von Steinbuechel, N. (2018). A multidimensional approach to post-concussion symptoms in mild traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 9, 1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dikmen, S., Machamer, J., Fann, J.R., and Temkin, N. (2010). Rates of symptom reporting following traumatic brain injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 16, 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ponsford, J.L., Downing, M.G., Olver, J., Ponsford, M., Acher, R., Carty, M., and Spitz, G. (2014). Longitudinal follow-up of patients with traumatic brain injury: outcome at two, five, and ten years post-injury. J. Neurotrauma 31, 64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olver, J.H., Ponsford, J.L., and Curran, C.A. (1996). Outcome following traumatic brain injury: a comparison between 2 and 5 years after injury. Brain Inj. 10, 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruet, A., Bayen, E., Jourdan, C., Ghout, I., Meaude, L., Lalanne, A., Pradat-Diehl, P., Nelson, G., Charanton, J., Aegerter, P., Vallat-Azouvi, C., and Azouvi, P. (2019). A detailed overview of long-term outcomes in severe traumatic brain injury eight years post-injury. Front. Neurol. 10, 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carroll, L.J., Cassidy, J.D., Peloso, P.M., Borg, J., von Holst, H., Holm, L., Paniak, C., and Pepin M., ; WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. (2004). Prognosis for mild traumatic brain injury: results of the who collaborating centre task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J. Rehabil. Med. (43 Suppl.), 84–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cassidy, J.D., Cancelliere, C., Carroll, L.J., Cote, P., Hincapie, C.A., Holm, L.W., Hartvigsen, J., Donovan, J., Nygren-de Boussard, C., Kristman, V.L., and Borg, J. (2014). Systematic review of self-reported prognosis in adults after mild traumatic brain injury: results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 3 Suppl., S132–S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hou, R., Moss-Morris, R., Peveler, R., Mogg, K., Bradley, B.P., and Belli, A. (2012). When a minor head injury results in enduring symptoms: a prospective investigation of risk factors for postconcussional syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 83, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Norrie, J., Heitger, M., Leathem, J., Anderson, T., Jones, R., and Flett, R. (2010). Mild traumatic brain injury and fatigue: a prospective longitudinal study. Brain Inj. 24, 1528–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stulemeijer, M., van der Werf, S., Borm, G.F., and Vos, P.E. (2008). Early prediction of favourable recovery 6 months after mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 79, 936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lowdon, I., Briggs, M. and Cockin, J. (1989). Post-concussional symptoms following minor head injury. Injury 20, 193–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Theadom, A., Parag, V., Dowell, T., McPherson, K., Starkey, N., Barker-Collo, S., Jones, K., Ameratunga, S. and Feigin, V.L. (2016). Persistent problems 1 year after mild traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal population study in New Zealand. Br J Gen Pract. 66(642), e16–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nelson, L.D., Temkin, N.R., Dikmen, S., Barber, J., Giacino, J.T., Yuh, E., Levin, H.S., McCrea, M.A., Stein, M.B., Mukherjee, P., Okonkwo, D.O., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Manley, G.T., Adeoye, O., Badjatia, N., Boase, K., Bodien, Y., Bullock, M.R., Chesnut, R., Corrigan, J.D., Crawford, K., Duhaime, A.C., Ellenbogen, R., Feeser, V.R., Ferguson, A., Foreman, B., Gardner, R., Gaudette, E., Gonzalez, L., Gopinath, S., Gullapalli, R., Hemphill, J.C., Hotz, G., Jain, S., Korley, F., Kramer, J., Kreitzer, N., Lindsell, C., Machamer, J., Madden, C., Martin, A., McAllister, T., Merchant, R., Noel, F., Palacios, E., Perl, D., Puccio, A., Rabinowitz, M., Robertson, C.S., Rosand, J., Sander, A., Satris, G., Schnyer, D., Seabury, S., Sherer, M., Taylor, S., Toga, A., Valadka, A., Vassar, M.J., Vespa, P., Wang, K., Yue, J.K., and Zafonte, R. (2019). Recovery after mild traumatic brain injury in patients presenting to US Level I trauma centers: a Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) study. JAMA Neurol. 76, 1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hartvigsen, J., Boyle, E., Cassidy, J.D., and Carroll, L.J. (2014). Mild traumatic brain injury after motor vehicle collisions: what are the symptoms and who treats them? A population-based 1-year inception cohort study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 3 Suppl., S286–S294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kashluba, S., Paniak, C., Blake, T., Reynolds, S., Toller-Lobe, G., and Nagy, J. (2004). A longitudinal, controlled study of patient complaints following treated mild traumatic brain injury. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 19, 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dischinger, P.C., Ryb, G.E., Kufera, J.A., and Auman, K.M. (2009). Early predictors of postconcussive syndrome in a population of trauma patients with mild traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma 66, 289–296; discussion, 296–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Theadom, A., Starkey, N., Barker-Collo, S., Jones, K., Ameratunga, S., and Feigin, V. (2018). Population-based cohort study of the impacts of mild traumatic brain injury in adults four years post-injury. PLoS One 13, e0191655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lange, R.T., Brickell, T.A., Ivins, B., Vanderploeg, R.D., and French, L.M. (2013). Variable, not always persistent, postconcussion symptoms after mild TBI in U.S. Military service members: a five-year cross-sectional outcome study. J. Neurotrauma 30, 958–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roe, C., Sveen, U., Alvsaker, K., and Bautz-Holter, E. (2009). Post-concussion symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury: influence of demographic factors and injury severity in a 1-year cohort study. Disabil. Rehabil. 31, 1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meares, S., Shores, E.A., Taylor, A.J., Batchelor, J., Bryant, R.A., Baguley, I.J., Chapman, J., Gurka, J., and Marosszeky, J.E. (2011). The prospective course of postconcussion syndrome: the role of mild traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology 25, 454–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kraus, J.F., Hsu, P., Schafer, K., and Afifi, A.A. (2014). Sustained outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury: results of a five-emergency department longitudinal study. Brain Inj. 28, 1248–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van der Vlegel, M., Polinder, S., Toet, H., Panneman, M.J.M., and Haagsma, J.A. (2021). Prevalence of post-concussion-like symptoms in the general injury population and the association with health-related quality of life, health care use, and return to work. J. Clin. Med. 10, 804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Voormolen, D.C., Cnossen, M.C., Polinder, S., Gravesteijn, B.Y., Von Steinbuechel, N., Real, R.G.L., and Haagsma, J.A. (2019). Prevalence of post-concussion-like symptoms in the general population in italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Brain Inj. 33, 1078–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dikmen, S., Machamer, J., and Temkin, N. (2017). Mild traumatic brain injury: Longitudinal study of cognition, functional status, and post-traumatic symptoms. J. Neurotrauma 34, 1524–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jakola, A.S., Muller, K., Larsen, M., Waterloo, K., Romner, B., and Ingebrigtsen, T. (2007). Five-year outcome after mild head injury: a prospective controlled study. Acta Neurol. Scand. 115, 398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lange, R.T., Lippa, S.M., French, L.M., Bailie, J.M., Gartner, R.L., Driscoll, A.E., Wright, M.M., Sullivan, J.K., Varbedian, N.V., Barnhart, E.A., Holzinger, J.B., Schaper, A.L., Reese, M.A., Brandler, B.J., Camelo-Lopez, V., and Brickell, T.A. (2020). Long-term neurobehavioural symptom reporting following mild, moderate, severe, and penetrating traumatic brain injury in U.S. Military service members. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 30, 1762–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Skandsen, T., Stenberg, J., Follestad, T., Karaliute, M., Saksvik, S.B., Einarsen, C.E., Lillehaug, H., Haberg, A.K., Vik, A., Olsen, A., and Iverson, G.L. (2021). Personal factors associated with postconcussion symptoms 3 months after mild traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 102, 1102–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCrea, M.A., Giacino, J.T., Barber, J., Temkin, N.R., Nelson, L.D., Levin, H.S., Dikmen, S., Stein, M., Bodien, Y.G., Boase, K., Taylor, S.R., Vassar, M., Mukherjee, P., Robertson, C., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Okonkwo, D.O., Markowitz, A.J., Manley, G.T., Adeoye, O., Badjatia, N., Bullock, M.R., Chesnut, R., Corrigan, J.D., Crawford, K., Duhaime, A.C., Ellenbogen, R., Feeser, V.R., Ferguson, A.R., Foreman, B., Gardner, R., Gaudette, E., Goldman, D., Gonzalez, L., Gopinath, S., Gullapalli, R., Hemphill, J.C., Hotz, G., Jain, S., Keene, C.D., Korley, F.K., Kramer, J., Kreitzer, N., Lindsell, C., Machamer, J., Madden, C., Martin, A., McAllister, T., Merchant, R., Ngwenya, L.B., Noel, F., Nolan, A., Palacios, E., Perl, D., Puccio, A., Rabinowitz, M., Rosand, J., Sander, A., Satris, G., Schnyer, D., Seabury, S., Sherer, M., Toga, A., Valadka, A., Wang, K., Yue, J.K., Yuh, E., and Zafonte, R. (2021). Functional outcomes over the first year after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury in the prospective, longitudinal TRACK-TBI Study. JAMA Neurol. 78, 982–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. King, N.S., Crawford, S., Wenden, F.J., Moss, N.E., and Wade, D.T. (1995). The rivermead post concussion symptoms questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J. Neurol. 242, 587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Teasdale, G., and Jennett, B. (1974). Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 2, 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Benjamini, Y., and Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Royal Stat. Soc. 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Asseltine, J., Kristman, V., Armstrong, J., and Dewan, N. (2020). The rivermead post-concussion questionnaire score is associated with disability and self-reported recovery six month after mild traumatic brain injury in older adults. Brain Inj. 34, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cooksley, R., Maguire, E., Lannin, N.A., Unsworth, C.A., Farquhar, M., Galea, C., Mitra, B., and Schmidt, J. (2018). Persistent symptoms and activity changes three months after mild traumatic brain injury. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 65, 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Theadom, A., Barker-Collo, S., Jones, K., Kahan, M., Te Ao, B., McPherson, K., Starkey, N., and Feigin, V. (2017). Work limitations 4 years after mild traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98, 1560–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Venkatesan, U.M., Lancaster, K., Lengenfelder, J., and Genova, H.M. (2021). Independent contributions of social cognition and depression to functional status after moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 31, 954–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lewis, F.D., and Horn, G.J. (2017). Depression following traumatic brain injury: impact on post-hospital residential rehabilitation outcomes. NeuroRehabilitation. 40, 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Donnell, M., Varker, T., Holmes, A., Ellen, S., Wade, D., Creamer, M., Silove, D., McFarlane, A., Bryant, R., and Forbes, D. (2013). Disability after injury: the cumulative burden of physical and mental health. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74, e137–e143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grauwmeijer, E., Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H., Haitsma, I.K., and Ribbers, G.M. (2012). A prospective study on employment outcome 3 years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93, 993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stacey, A., Lucas, S., Dikmen, S., Temkin, N., Bell, K.R., Brown, A., Brunner, R., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Watanabe, T.K., Weintraub, A., and Hoffman, J.M. (2017). Natural history of headache five years after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 34, 1558–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Erler, K.S., Kew, C.L., and Juengst, S.B. (2020).Participation differences by age and depression 5 years after moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 32, 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Seabury, S.A., Gaudette, E., Goldman, D.P., Markowitz, A.J., Brooks, J., McCrea, M.A., Okonkwo, D.O., Manley, G.T., Adeoye, O., Badjatia, N., Boase, K., Bodien, Y., Bullock, M.R., Chesnut, R., Corrigan, J.D., Crawford, K., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Dikmen, S., Duhaime, A.C., Ellenbogen, R., Feeser, V.R., Ferguson, A., Foreman, B., Gardner, R., Giacino, J., Gonzalez, L., Gopinath, S., Gullapalli, R., Hemphill, J.C., Hotz, G., Jain, S., Korley, F., Kramer, J., Kreitzer, N., Levin, H., Lindsell, C., Machamer, J., Madden, C., Martin, A., McAllister, T., Merchant, R., Mukherjee, P., Nelson, L., Noel, F., Palacios, E., Perl, D., Puccio, A., Rabinowitz, M., Robertson, C., Rosand, J., Sander, A., Satris, G., Schnyer, D., Sherer, M., Stein, M., Taylor, S., Temkin, N., Toga, A., Valadka, A., Vassar, M., Vespa, P., Wang, K., Yue, J., Yuh, E., and Zafonte, R. (2018). Assessment of follow-up care after emergency department presentation for mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: results from the TRACK-TBI Study. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e180210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.