Abstract

Community health advisor (CHA) interventions increase colorectal cancer (CRC) screening rates. African Americans experience CRC disparities in incidence and mortality rates compared to whites in the US. Focus groups and learner verification were used to adapt National Cancer Institute CRC screening educational materials for delivery by a CHA to African American community health center patients. Such academic-community collaboration improves adoption of evidence-based interventions. This short article describes the adaptation of an evidence-based cancer education intervention for implementation in an African American community.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, colorectal cancer screening, health disparities, African Americans

Introduction

Evidence-based public health involves merging science-based interventions and programs with community-identified needs and capacity aiming for the goal of improving population health (Kohatsu et al., 2004). Patient navigation for colorectal cancer (CRC) is an evidence-based approach to improve patient outcomes in the areas of cancer screening, diagnostic procedures, and follow-up for cancer treatment (Leach et al., 2021). A recent systematic review reported that colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer screening rates were higher in patients who received patient navigation services, which can be very impactful for African Americans who experience cancer health disparities (Nelson et al., 2020). African Americans have lower CRC screening rates than whites, and consequently, there have been numerous intervention studies to increase screening rates for African Americans through patient navigation, technological innovations, and improvements to appointment scheduling or reminder systems (Boutsicaris et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2020).

As one of the four major cancer sites, CRC mortality rates have been declining since 1980, but in recent years these declines have slowed (Siegel et al., 2021). African Americans experience CRC disparities in mortality rates which can be attributed to persistent income inequalities and its effects on access to healthcare and lower screening adherence, which may result in late-stage diagnosis and lower survival rates (DeSantis et al., 2019). According to the latest available data, the mortality rate for African Americans is 36% higher than whites (18.5 per 100,000 population compared to 13.6 per 100,000 population for whites), with more pronounced disparities for men compared to women (Siegel et al., 2021). CRC incidence rates are also higher among African Americans compared to whites, and in terms of geographic variation, incidence rates in the US South are higher compared to other regions of the US, which is another factor to consider especially with the rise in early-onset colorectal cancer (Siegel et al., 2019). This short article summarizes the adaptation and refinement of a community health advisor (CHA) intervention which employs evidence-based patient navigation approaches and includes educational materials from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Screen to Save (S2S) Colorectal Cancer Outreach and Screening Initiative (National Cancer Institute, 2021).

Educational Materials Development

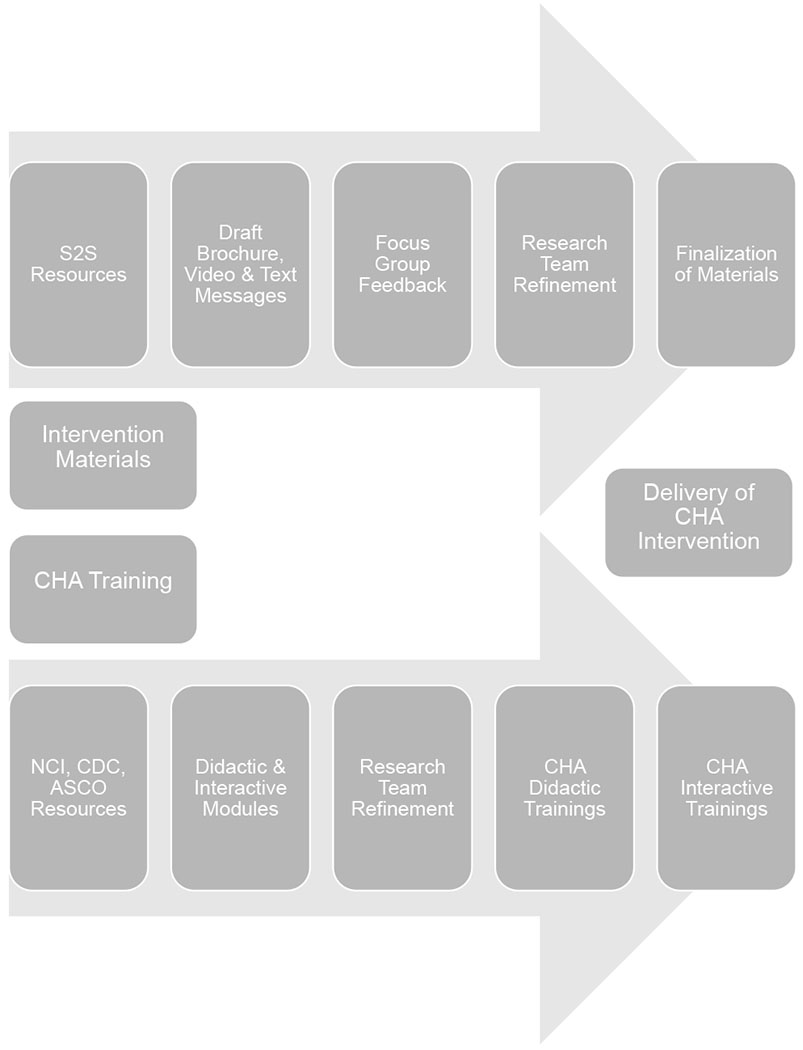

S2S is a national initiative which aims to enhance CRC outreach and screening. According to the NCI, the aim is to increase CRC screening rates among men and women ages 50 and older from racially and ethnically diverse communities and in rural areas (National Cancer Institute, 2021). In alignment with the NCI’s goal of increasing CRC screening rates, the Test Up Now Education Program (TUNE-UP) created and adapted materials which consisted of an educational brochure and a narrated presentation video - based on the S2S materials - to deliver a culturally tailored intervention to African Americans living in low-income communities. The intervention is delivered by the CHA to African Americans in North Florida who are patients of community health centers and are not up to date with CRC screening. This research project is part of a Research Centers in Minority Institutions grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities which is focused on addressing cancer health disparities in Leon County and Gadsden County, Florida. Gadsden County is the only county in Florida with a majority African American population. The utilization of a CHA and the adaptation of S2S is an evidence-based approach for promoting CRC screening. The S2S initiative has been shown to be effective based on the published findings from the national outreach initiative which leverages NCI-designated Cancer Centers. The program evaluation reported 3,183 pre/post surveys were obtained from participants, ages 50 to 74, during 347 educational events (Whitaker et al., 2020). Results demonstrated an increase in colorectal cancer-related knowledge and revealed a positive association between attending educational events and intention to receive subsequent CRC screening. In addition, 82% of participants who received a CRC screening three months after attending the events successfully obtained their screening results (Whitaker et al., 2020). The results of the S2S initiative suggest the effectiveness of the community-based approach to achieve positive outcomes in terms of CRC screening adherence in diverse populations.

Focus Group Learner Verification

The TUNE-UP study began with formative research with African American community participants using focus group methodology. The objective of the focus groups was to explore knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CRC and CRC screening as well as to obtain learner verification of the educational brochure. This was an important step to ensure that the educational materials were comprehensible to the intended audience and provided easily digestible information on CRC screening. In this article, we describe the sections of the educational brochure and the adaptation of the presentation, but the complete findings from the focus group results have been published elsewhere (Luque et al., 2021).

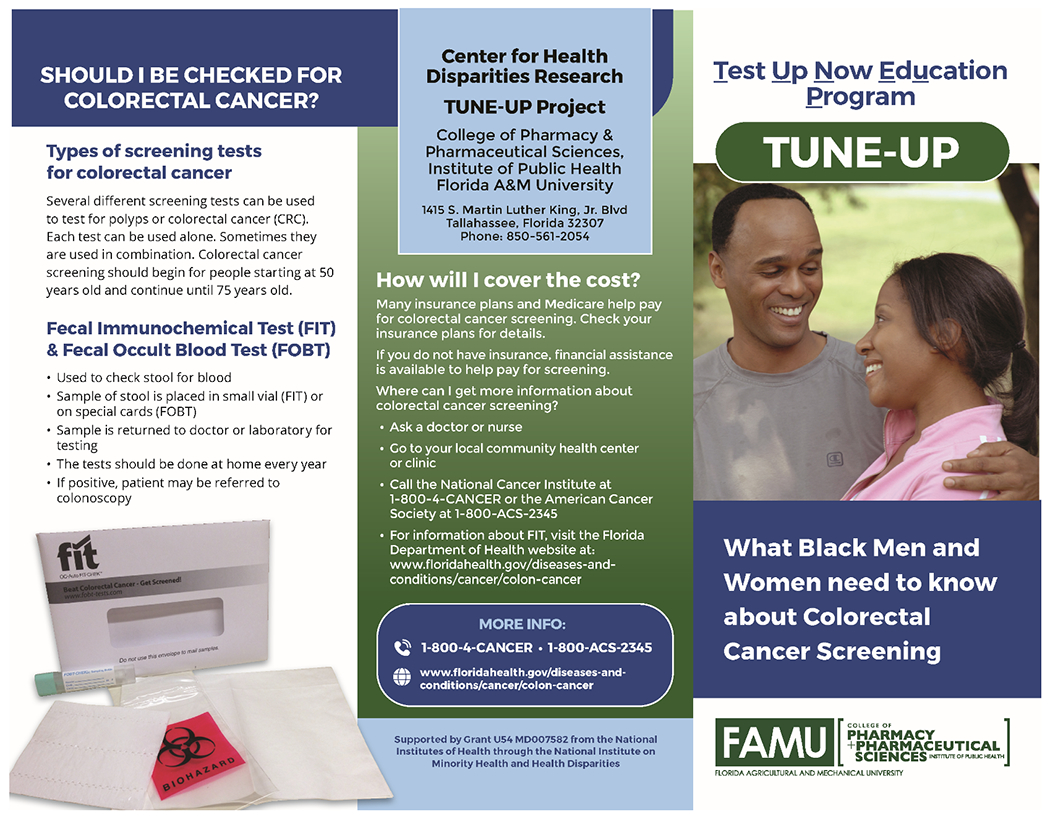

The brochure was designed as a tri-fold brochure. For the initial version, the brochure cover had a header of the study name, stock photos of a group of friends walking for exercise and an older couple with the TUNE-UP title and university logo and underneath, the text What Black Men and Women need to know about Colorectal Cancer Screening. The back cover contained TUNE-UP contact details, information on covering the cost of CRC screening and where to get more information from the American Cancer Society and the NCI. The inside flap covered information on the types of available screening tests with an emphasis on stool-based tests and a picture of the test kit. Most importantly for our study, under the description of the Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) were bullet points describing that the FIT is used to check stool for blood, the stool sample is placed in a small vial, and is then returned to the doctor or laboratory for testing. In addition, it was described that the FIT is done every year, and in the case of a positive FIT, the patient is referred to colonoscopy. The inside panel 1 showed a picture of the human colon with polyps and a bulleted list of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for CRC. The inside panel 2 showed a picture of the anatomy of the colon and a definition of CRC. The inside panel 3 described what happens after a CRC screening, details on the colonoscopy procedure and answered some questions about CRC screening with a short testimonial on how to overcome the fear of completing the test.

Based on the feedback we received from focus group meetings 1 and 2, changes were made to the brochure and the second version was created. Specifically, the color was changed to make it more attractive, texts were made bold for ease of reading, a picture of a famous person who had died from CRC was added, detailed formatting was done and the picture of the anatomical figure depicting the colon was edited by darkening the skin tone so it did not appear to be a white person - based on feedback from the focus groups. This version of the brochure was used for focus groups 3, 4, and 5.

Focus group feedback was further used to make changes to the brochure for a final version. A professional design of the entire brochure was done, and the color scheme changed, using two major colors – blue signifying CRC and green signifying our university’s school colors. On the inside of the brochure, a picture of a newer test kit replaced the older kit picture, and a photo of a well-known Black couple in the community was inserted. This final version was used for focus group meetings 6 and 7 with no further suggested changes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

TUNE-UP Brochure

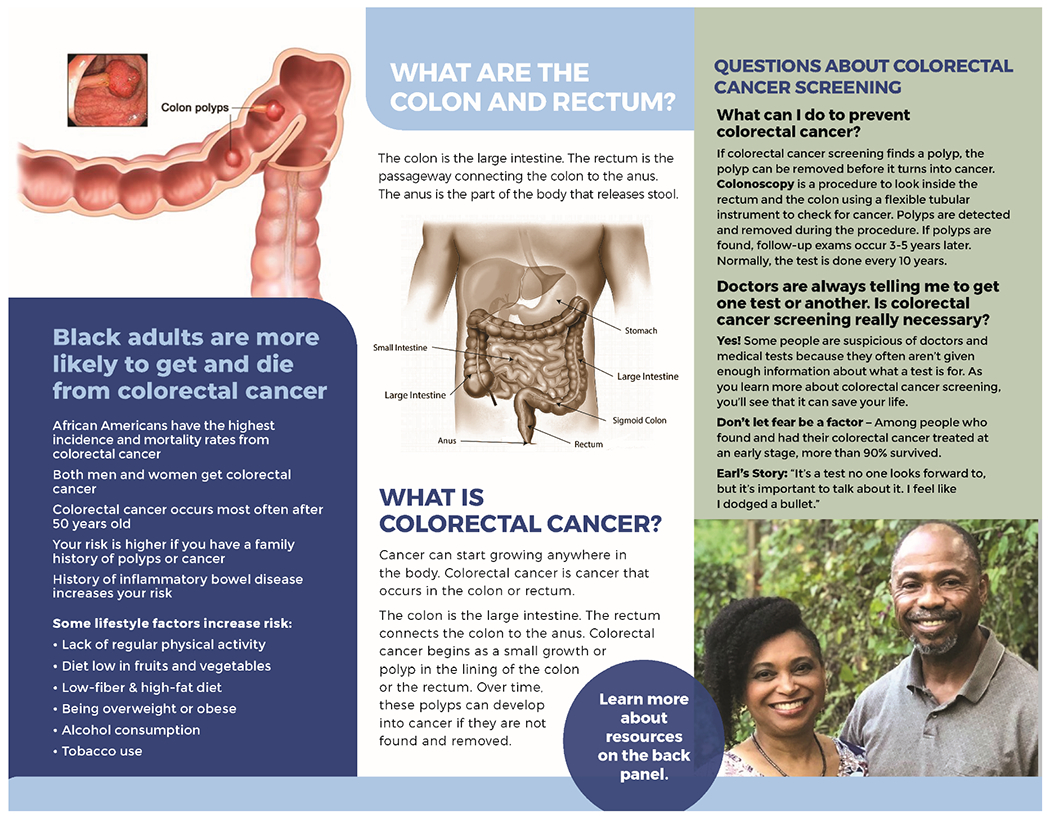

Community Health Advisor

CHAs also known as community health workers, peer health educators, promotoras, lay health advocates and other similar titles are trusted public health workers who possess intimate knowledge about the communities they serve and facilitate access to health and social services with improved quality and cultural competency. CHAs may be paid employees within a health care system or volunteer patient advocates, and for increasing cancer screening, their work is cost-effective (Attipoe-Dorcoo et al., 2021). Improved adherence to recommended health practices is a recognized benefit of CHA services and several reviews of CHA CRC screening interventions have shown a positive effect on receipt of screening (Naylor et al., 2012; Rawl et al., 2012). In the context of our current behavioral clinical trial, a CHA was trained by the research team to deliver a 6-week intervention consisting of an initial face-to-face or virtual CRC educational presentation, two weeks of phone-call follow-up, and three weeks of text message follow-up. The intervention’s one-on-one education, small media, follow-up reminders, and reduction of structural barriers to screening aligns with client-oriented recommendations of the Community Guide to Preventive Services (Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2021). We hypothesize that the CHA intervention described here and utilized in the behavioral clinical trial will demonstrate positive CRC screening outcomes compared to a “usual care” approach among a population of African Americans not up to date with current screening recommendations. We prioritized designing a CHA screening intervention for effectiveness in promoting CRC screening among African Americans who suffer disproportionately from CRC (Figure 2). Therefore, we sought to identify and recruit a CHA from our local African American community. We engaged African American community leaders for assistance promoting the opportunity. The candidate selected through this outreach had been a member of the community for many years, had provided community education around other health topics, was comfortable discussing CRC with African American women and men, and expressed desire to work in service to the community. To prepare the CHA to deliver the CRC educational intervention, we developed and delivered the didactic and interactive training described below.

Figure 2.

CHA Intervention Development

CHA Training

The CHA training consisted of three didactic and two interactive sessions focused on colorectal cancer education, the role of the CHA, intervention components, and practice interactions using role playing. The training was delivered by three study investigators (JL, CG, KW) and the project coordinator (MV). The cancer module provided an overview of cancer and CRC and covered CRC incidence, risk factors, common symptoms, lifestyle changes, prevention, and screening recommendations and options (i.e., stool-based tests, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and CT colonography). Didactic materials were drawn from reliable sources such as the NCI, the CDC, and the American Society of Clinical Oncologists (ASCO). The didactic PowerPoint modules included hyperlinks to all information sources and were supplemented with graphics (e.g., anatomical images) and YouTube video tutorials. Delivery of the didactic modules was recorded as a training product for future reference. The training also discussed the importance of intervention fidelity and skills for maintaining fidelity of the CHA educational intervention using a conversation script and presenting different possible scenarios. Additionally, an introduction to motivational interviewing was provided and the CHA trained on using basic principles of motivational interviewing to help them achieve success with participants who present with barriers to screening and need support or counseling (Luckmann et al., 2013). In the final training session, the CHA completed practice sessions to simulate CHA-client interaction situations, using talking points, followed by feedback from the project coordinator, who assessed fidelity using checklists.

Refining the CHA Intervention

The CHA educational presentation to intervention arm participants includes the use of NCI CRC resources and materials, including the approximately 11-minute S2S PowerPoint presentation video that was adapted and created. Using pictures, charts and figures, the video begins with an initial description of CRC, its incidence, risk factors and prevention, with a highlight on health disparities, comparing CRC incidence and mortality rates between the black and white U.S. population. Screening recommendations and options are further explained, with a focus on colonoscopy and the stool-based test. The final part of the video transitions to provide information on the TUNE-UP study including eligibility criteria, study procedures, and details on participant incentives.

The CHA meets with participants at their preferred location to provide the intervention. After using a tablet to show the S2S video to the study participant and allowing for questions/discussion, the CHA shows the participant a second video which explains how to complete a stool-based CRC screening test (FIT kit) at home. This 5-minute CRC screening patient tutorial video was obtained by the study team through agreement with the manufacturer. Following presentation of the second video, the CHA again engages the participant to allow for questions or discussion. At the conclusion of the face-to-face meeting, the CHA informs the participant that the CHA will check in with them by phone a week later to ask if they were successful in completing and mailing in their FIT kit. Intervention arm participants receive this 30-minute face-to-face meeting followed by two CHA phone calls in one-week intervals over a period of three weeks beginning within one month following baseline survey completion. Using fidelity checklists for weeks 1-3, the CHA records qualitative data from the intervention session and subsequent phone calls. The duration of educational intervention sessions depends on the participants’ inquiries and typically last 25-35 minutes. Follow-up phone calls for weeks 2 and 3 are generally short in duration.

To maintain intervention fidelity, the CHA follows a conversation guide/standard script and completes checklists for the face-to-face meeting and phone calls. The CHA takes notes of each interaction to document call length, tone, and deviations from the script. Participants are already knowledgeable regarding FIT screenings at weeks 2-3 and therefore the fidelity checklists for weeks 2-3 document receipt or non-receipt, completion, and mailing in of FIT screenings, and to address any concerns that the participant raises following the intervention. The CHA implements motivational interviewing to address any questions or concerns the participant may have about the educational presentation. Participants receive an additional text message reminder once a week for an additional three-week period.

The personalized text messages have positive tones and include short messages about the importance of CRC screening (Weaver et al., 2015). The three text messages selected were the most preferred by focus group participants during the learner verification phase. The initial text message that is sent in week 4 of the intervention states, “Screening for colon cancer saves lives.” The text message sent in week 5 states, “Seven out of ten people diagnosed with colorectal cancer often have no obvious signs and symptoms, regular screening is the key to early detection.” The final text message sent in week 6 states, “Don’t let fear of diagnosis stop you from getting tested, early detection is key to prevent colon cancer. Get tested today.” Acceptability of the CHA intervention is assessed by two items included in the 3-month phone survey with intervention arm participants. One question asks participants to rank on a Likert scale their satisfaction with support received from the CHA, and the second item asks if they would recommend working with a CHA to others who have not been screened.

Conclusion

Academic-community partnerships provide a mechanism to test intervention strategies to increase CRC screening and address cancer health disparities (Meade et al., 2011). By seeking community input on the adaptation of the S2S evidence-based CRC screening education resources as part of a CHA intervention, the resulting intervention is received well in the community. In addition, the engagement of the community health centers and other community partners to advertise the study (churches, small businesses) is being used to leverage participation of African American patients in the community. The findings from these academic-community research partnerships will generate knowledge about how to adapt evidence-based community health educator programs in both community and clinical settings.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge support of the U54 RCMI Center Office – Ms. Leola Hubert-Randolph and Ms. Gloria O. James–Academic Support Services, Florida A&M University College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Institute of Public Health and U54 RCMI Principal Investigator, Dr. Karam F. Soliman. We acknowledge study team members Dr. Cynthia M. Harris, Dr. Askal Ali, and Dr. Gebre Kiros. We also acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Alexandria Washington with help facilitating in-person focus groups.

This article was supported by funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54 MD007582. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Attipoe-Dorcoo S, Chattopadhyay SK, Verughese J, Ekwueme DU, Sabatino SA, Peng Y, and Community Preventive Services Task, Force (2021). Engaging community health workers to increase cancer screening: a Community Guide systematic economic review. Am. J. Prev. Med 60, e189–e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutsicaris AS, Fisher JL, Gray DM, Adeyanju T, Holland JS, and Paskett ED (2021). Changes in colorectal cancer knowledge and screening intention among Ohio African American and Appalachian participants: The Screen to Save initiative. Cancer Causes Control 32, 1149–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SN, Christy SM, Chavarria EA, Abdulla R, Sutton SK, Schmidt AR, Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Simmons VN, Ufondu CB, et al. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent, targeted, low-literacy educational intervention compared with a nontargeted intervention to boost colorectal cancer screening with fecal immunochemical testing in community clinics. Cancer 123, 1390–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, and Siegel RL (2019). Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 69, 211–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guide to Community Preventive Services (2021). Cancer screening: interventions engaging community health workers. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/cancer.

- Kohatsu ND, Robinson JG, and Torner JC (2004). Evidence-based public health: an evolving concept. Am. J. Prev. Med 27, 417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach KM, Granzow ME, Popalis ML, Stoltzfus KC, and Moss JL (2021). Promoting colorectal cancer screening: A scoping review of screening interventions and resources. Prev. Med 147, 106517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckmann R, Costanza ME, Rosal M, White MJ, and Cranos C (2013). Referring patients for telephone counseling to promote colorectal cancer screening. Am. J. Manag. Care 19, 702–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Vargas M, Wallace K, Matthew OO, Tawk R, Ali AA, Kiros GE, Harris CM, and Gwede CK (2021). Engaging the community on colorectal cancer screening education: focus group discussions among African Americans. J. Cancer Educ Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CD, Menard JM, Luque JS, Martinez-Tyson D, and Gwede CK (2011). Creating community-academic partnerships for cancer disparities research and health promotion. Health Promot. Pract 12, 456–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SJ, Sly JR, Gaffney KB, Jiang Z, Henry B, and Jandorf L (2020). Development of a tablet app designed to improve African Americans’ screening colonoscopy rates. Transl. Behav. Med 10, 375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (2021). Screen to Save: NCI Colorectal Cancer Outreach and Screening Initiative (Washington, D.C.). https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/crchd/inp/screen-to-save. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor K, Ward J, and Polite BN (2012). Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med 27, 1033–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Wagner J, Jungbauer R, Fu R, Kondo K, Stillman L, and Quinones A (2020). Effectiveness of patient navigation to increase cancer screening in populations adversely affected by health disparities: a meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med 35, 3026–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawl SM, Menon U, Burness A, and Breslau ES (2012). Interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening: an integrative review. Nursing Outlook 60, 172–181 e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Medhanie GA, Fedewa SA, and Jemal A (2019). State variation in early-onset colorectal cancer in the United States, 1995–2015. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 111, 1104–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, and Jemal A (2021). Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA: Cancer J. Clin 71, 7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Ellis SD, Denizard-Thompson N, Kronner D, and Miller DP (2015). Crafting appealing text messages to encourage colorectal cancer screening test completion: a qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 3, e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DE, Snyder FR, San Miguel-Majors SL, Bailey LO, and Springfield SA (2020). Screen to Save: Results from NCI’s colorectal cancer outreach and screening initiative to promote awareness and knowledge of colorectal cancer in racial/ethnic and rural populations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 29, 910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]