Abstract

The yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase is an assembly of 28 subunits of 17 types of which 3 (subunits 6, 8, and 9) are encoded by mitochondrial genes, while the 14 others have a nuclear genetic origin. Within the membrane domain (FO) of this enzyme, the subunit 6 and a ring of 10 identical subunits 9 transport protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane coupled to ATP synthesis in the extra-membrane structure (F1) of ATP synthase. As a result of their dual genetic origin, the ATP synthase subunits are synthesized in the cytosol and inside the mitochondrion. How they are produced in the proper stoichiometry from two different cellular compartments is still poorly understood. The experiments herein reported show that the rate of translation of the subunits 9 and 6 is enhanced in strains with mutations leading to specific defects in the assembly of these proteins. These translation modifications involve assembly intermediates interacting with subunits 6 and 9 within the final enzyme and cis-regulatory sequences that control gene expression in the organelle. In addition to enabling a balanced output of the ATP synthase subunits, these assembly-dependent feedback loops are presumably important to limit the accumulation of harmful assembly intermediates that have the potential to dissipate the mitochondrial membrane electrical potential and the main source of chemical energy of the cell.

Keywords: ATP synthase, mitochondria, mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondria DNA, yeast, mitochondrial gene expression

Introduction

Mitochondria support aerobic respiration and produce the bulk of cellular ATP through the process of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (Saraste 1999). Typically, OXPHOS involves 5 hetero-oligomeric protein complexes (numbered I–V) that are located in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Complexes I–IV transfer to oxygen electrons from carbohydrates and fatty acids coupled to the transport of protons from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space, and the resulting energy-rich transmembrane proton gradient is used by the Complex V (ATP synthase) to make ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate.

The structural genes of the mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes are located in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. As such, 2 separate translation machineries, one cytosolic and the other inside the mitochondrion, are utilized to synthesize their gene products (Ott and Herrmann 2010). A plethora of proteins that do not belong to the OXPHOS complexes assist translation and assembly of their subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Fox 1996, 2012; Herrmann et al. 2013; Ott et al. 2016). A subset of these “helper” proteins are known to interact with the 5′-UTR (Untranslated Region) of a specific mitochondrial mRNA transcript, and in some instances, with the translation product as well, and these observations have led investigators to postulate the existence of regulatory feedback loops that couple translation and assembly of mitochondrial gene products (Fox 2012; Fontanesi 2013; Herrmann et al. 2013; Ott et al. 2016). The most thoroughly investigated example is Mss51, which facilitates Cox1 translation and assembly in complex IV (Soto et al. 2012). Studies have shown that Mss51 binds first to the 5′-UTR of the COX1 mRNA, where it activates translation, and then to the newly synthesized Cox1 protein until Cox1 is assembled with its partner subunits (Perez-Martinez et al. 2003; Barrientos et al. 2004; Pierrel et al. 2007; Mick et al. 2010). The posttranslational activity of Mss51 is similar to that described for another mitochondrial protein, which is a small complex composed of Cbp3 and Cbp6 polypeptides that maintains association with newly translated cytochrome b through its acquisition of heme cofactors and assembly with the nucleus-encoded subunits of complex III (Rodel 1986; Chen and Dieckmann 1994; Dieckmann and Staples 1994; Gruschke et al. 2011; Hildenbeutel et al. 2014). Similarly, the Sov1 protein assists in yeast the translational activation and assembly of the mtDNA-encoded Var1 subunit of the mitochondrial ribosome (Seshadri et al. 2020).

Much less is known about the regulation of yeast ATP synthase biogenesis. This is an assembly of 28 subunits of 17 types that are encoded by 3 mitochondrial (ATP6, ATP8, and ATP9) and 14 nuclear genes. This enzyme, known as the F1FO complex, is organized into a largely hydrophobic domain (FO) that transports protons through the membrane, and a hydrophilic domain (F1) in the mitochondrial matrix where ATP is synthesized. The ATP6 and ATP9 genes encode subunits of the FO (6/a and 9/c) that form an integral proton channel made of one subunit 6 and an oligomeric ring of 10 subunits 9 (910-ring). During proton translocation, the 910-ring rotates, and this induces conformational changes in the F1 that promote ATP synthesis. The ATP8 gene encodes a membrane-embedded protein (the subunit 8) that stabilizes the proton channel of ATP synthase. ATP9 is co-transcribed with tRNAser and a mitochondrial ribosome subunit gene (VAR1), whereas ATP8 and ATP6 are co-transcribed with COX1 (Christianson and Rabinowitz 1983; Zassenhaus et al. 1984; Finnegan et al. 1991). Processing of the primary transcripts produces a major ATP9 mRNA with a 0.63 kb long 5′-UTR, and near equal amounts of 2 bicistronic ATP8,6 mRNAs that differ by the length of their 5′-UTR (Foury et al. 1998).

Among the proteins that are associated with the biogenesis pathway for subunits 6, 8, and 9, four (Nca2, Nca3, Aep3, and Nam1) contribute to ATP8/6 transcripts stability (Asher et al. 1989; Pelissier et al. 1992, 1995; Ellis et al. 2004). A role for Aep3 in translation of subunit 8 has also been reported (Barros and Tzagoloff 2017). Other proteins include Atp22, which activates subunit 6 translation (Zeng et al. 2007a), and Smt1, which represses translation of both subunits 6 and 8 (Rak et al. 2016). The stability of the ATP9 transcript is dependent on a 35 kDa C-terminal cleavage fragment of Atp25 (Zeng et al. 2008) that is released in the matrix by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (Woellhaf et al. 2016). Two more proteins with activities linked to the ATP9 mRNA are Aep1 and Aep2 (Ackerman et al. 1991; Finnegan et al. 1991, 1995; Payne et al. 1991, 1993; Ziaja et al. 1993). Some studies have suggested a role for these proteins in ATP9 mRNA stability/processing (Payne et al. 1991; Ziaja et al. 1993), while others have led investigators to propose that they activate translation (Payne et al. 1993; Ellis et al. 2004).

Another subgroup of yeast nuclear gene products associated with ATP synthase biogenesis assists oligomerization of its subunits. Two such proteins, Atp11 and Atp12, are essential for creating the [αβ]3 hexamer, which houses the catalytic sites for ATP synthesis and contributes ∼85% of the mass in F1 (Ackerman and Tzagoloff 1990b; Wang and Ackerman 2000; Wang et al. 2000, 2001; Ackerman 2002; Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2005). A third protein that is part of this process, Fmc1, is necessary for Atp12 folding/stability at elevated temperature (36°C) (Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2001, 2005). Other work has shown that a complex of 2 proteins, Ina22 and Ina17, facilitates assembly of ATP synthase peripheral stalk, which is a structure protruding from the membrane and that contacts the surface of the F1 to prevent rotation of the [αβ]3 hexamer during catalysis (Lytovchenko et al. 2014). In an early model of F1FO assembly, the 910-ring was proposed to assemble spontaneously (Arechaga et al. 2002). This was challenged by later studies suggesting that oligomerization of the 910-ring is chaperoned by a 32 kDa N-terminal fragment of Atp25 (Zeng et al. 2008). This fragment is homologous to the bacterial ribosome-silencing factor and was found associated with the mitochondrial ribosome (Woellhaf et al. 2016). Two proteins (Atp10 and Atp23) have been assigned roles in procuring the assembly/stability of subunit 6 (Paul et al. 2000; Tzagoloff et al. 2004; Osman et al. 2007; Zeng et al. 2007c). Atp10 was shown to associate in a physical complex with newly translated subunit 6 and promote a favorable interaction with the 910-ring (Tzagoloff et al. 2004). Atp23 was identified to be a protease that cleaves the first 10 amino acid residues of the nascent subunit 6 polypeptide and has been linked also to folding the processed protein (Osman et al. 2007; Zeng et al. 2007b, 2007c). Finally, the interaction of subunit 6 with the 910-ring has been reported to depend on Oxa1 (Jia et al. 2007), which is a protein translocase involved in the insertion of certain mitochondrial and nuclear gene products into the inner membrane (Altamura et al. 1996; Herrmann et al. 1997; Hell et al. 2001).

Herein we report that translation of subunit 6 and 9 is enhanced in mutant strains with specific defects in the assembly of these proteins. These translation modifications involve assembly intermediates interacting with these proteins within the final ATP synthase and cis-regulatory sequences that control gene expression in the organelle. These findings suggest that the subunit 6 is part of an assembly-dependent feedback loop that is different from a previously reported regulatory model for this protein (Rak et al. 2009, 2011). Additionally, they contradict the generally accepted view that the 910-ring forms separately, independently of any other ATP synthase component.

Materials and methods

Growth media

The media used for growing yeast were: YPGA (rich glucose): 1% Bacto yeast extract, 1% Bacto peptone, 2% glucose, 40 mg/L adenine; YPGalA (rich galactose): 1% Bacto yeast extract, 1% Bacto Peptone, 2% galactose, 40 mg/L adenine; YPGlyA (rich glycerol): 1% Bacto yeast extract, 1% Bacto peptone, 2% glycerol, 3% ethanol, 40 mg/L adenine; complete synthetic medium (CSM) lacking 1 amino acid (arginine, leucine, or tryptophan) or base (uracil): glucose or galactose 20 g/L, yeast nitrogen base 1.7 g/L, ammonium sulfate 5 g/L, adenine 40 mg/L, and CSM single drop-out powder 0.74-0.77 g/L (see MB Biochemicals for instruction). The liquid media were solidified with 2% of Bacto agar. Doxycycline was used at the concentration of 40 µg/mL. G418 sulfate was used at 200 µg/mL.

Construction and isolation of yeast strains

The genotypes of strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All the mutant strains are derivatives of wild-type strain MR6 (Rak et al. 2007b). Deletion of AEP1, AEP2, and ATP25 in wild-type strain MR6 (Rak et al. 2007b) was done using KANMX4 DNA-cassettes [amplified with Low and Up primers (Table 2)] and genomic DNA was isolated from aep1Δ, aep2Δ, and atp25Δ deletion strains from Euroscarf. The deletions of AEP1, AEP2, and ATP25 in MR6 were PCR-verified with Ver-KanMx primers (Table 2). Prior to deleting AEP1, AEP2, or ATP25, the MR6 strain was transformed with the pAM19 plasmid, which encodes the PaAtp9-5 gene of Podospora anserina (here referred to as ATP9-nuc) (Bietenhader et al. 2012). In the presence of pAM19, aep1Δ, aep2Δ, and atp25Δ strains have a much less reduced propensity to produce ρ−/ρ0 cells lacking functional mtDNA. The ectopic integration of ATP6 in mtDNA, with and without the atp6-L173P mutation, was done using a previously described procedure (Steele et al. 1996). As a first step, the WT and mutated ATP6 genes flanked by 75 bp of the 5′-UTR and 118 bp of the 3′-UTR of COX2 were PCR-amplified using GeneArt Invitrogen Gene Synthesis technology and cloned at the EcoRI site of pPT24 plasmid (Thorsness and Fox 1993), giving plasmids pRK49 and pRK77, respectively. These plasmids were introduced into mitochondria of the ρ0 strain DFS160 by biolistic transformation using the Particle Delivery Systems PDS-1000/He (BIO-RAD) as previously described (Bonnefoy and Fox 2001), giving the petite synthetic ρ– strains RKY89-2 and RKY116-2. These strains were crossed with the strain RKY83 (Bader et al. 2020) in which the entire coding sequence of ATP6 is replaced with ARG8m (atp6::ARG8m) and where the gene COX2 is partially deleted (cox2-62). The RKY89-2 × RKY83 and RKY116-2 × RKY83 crosses produced clones (RKY112 and RKY117, respectively) that were arginine auxotrophic and able to grow in rich glycerol (YPGlyA). The ectopic integration of the WT or the mutated ATP6 gene in strains RKY112 and RKY117 in the intergenic region of COX2 was PCR-verified with primers oAtp6-2, oAtp6-4, o5′UTR2 and o5′UTR1 primers (Table 2). The modified mitochondrial genetic loci in strains RKY112 and RKY117 are schematically represented in Fig. 4a.

Table 1.

Genotypes and sources of yeast strains.

| Strain | Nuclear genotype | mtDNA | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| MR6 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 CAN1 | ρ+ | Rak et al. (2007b) |

| D273-10B/60 | MATα met6 | ρo | van Dijken et al. (2000) |

| DFS160 | MATα leu2Δ ura3-52 ade2-101 arg8::URA3 kar1-1 | ρo | Steele et al. (1996) |

| NB40-3C | MATa lys2 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3ΔHinDIII arg8::hisG | ρ+cox2-62 | Steele et al. (1996) |

| MR10 (atp6Δ) | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 | ρ+ atp6::ARG8m | Rak et al. (2007b) |

| SDC30 | MATα leu2Δ ura3-52 ade2-101 arg8::URA3 kar1-1 | ρ− COX2 ATP6 | Rak et al. (2007b) |

| RKY20 | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 CAN1 | ρ+ atp6-L173P | Kucharczyk et al. (2009) |

| RKY12 | MATα leu2Δ ura3-52 ade2-101 arg8::URA3 kar1-1 | ρ− atp6-L173P | Kucharczyk et al. (2009) |

| RKY26 (atp9Δ) | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 CAN1 | ρ+atp9::ARG8m | Bietenhader et al. (2012) |

| AMY10 (atp9Δ) | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8Δ::HIS3 CAN1/PaATP9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp9::ARG8m | Bietenhader et al. (2012) |

| RKY83 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 CAN1 | ρ+cox2-62 atp6::ARG8m | Bader et al. (2020) |

| RKY89 | MATα leu2Δ ura3-52 ade2-101 arg8∷ URA3 kar1-1 | ρ−5′-UTRCOX2 ATP6WT | Bader et al. (2020) |

| RKY112 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 CAN1 | ρ+5′-UTRCOX2 ATP6WT | Bader et al. (2020) |

| RKY116 | MATα leu2Δ ura3-52 ade2-101 arg8:: URA3 kar1-1 | ρ− 5′-UTRCOX2 atp6-L173P | This study |

| RKY117 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 CAN1 | ρ+ 5′-UTRCOX2 atp6-L173P | This study |

| RKY39 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8:: HIS3 | ρ+ atp6-W126R | Kucharczyk et al. (2013) |

| RKY39-R1G | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8:: HIS3 | ρ+ atp6-R126I | Kucharczyk et al. (2013) |

| RKY39-R5G | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8:: HIS3 | ρ+ atp6-R126G | Kucharczyk et al. (2019) |

| RKY39-6G | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 | ρ+atp6-W126R R169I | Kucharczyk et al. (2019) |

| RKY39-R16G | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8:: HIS3 | ρ+ atp6-R126K | Kucharczyk et al. (2019) |

| AKY36 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp1::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY37 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp1::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY40 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp11::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY41 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp11::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY42 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY43 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY76 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 fmc1::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY77 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 fmc1::KANMX4 CAN1 | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY60 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 aep1::KANMX4 CAN1/PaATP9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY63 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 aep1:: KANMX4 CAN1/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY61 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 aep2::KANMX4 CAN1/PaATP9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY64 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 aep2:: KANMX4/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY65 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+ | This study |

| AKY75 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp6-L173P | This study |

| AKY121 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+ | This study |

| FG146 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp6::ARG8m | This study |

| FG151 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4 | ρ+atp6::ARG8m | This study |

| FG152 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp6::ARG8m | This study |

| FG153 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4 | ρ+atp9::ARG8m | This study |

| FG154 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 CAN1 arg8::HIS3 atp12::KANMX4/PaAtp9-5 (ATP9-nuc) | ρ+atp9::ARG8m | This study |

Table 2.

Primers.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Atp11-Up | 5′-GTGCCGTATCAGTAGTCGTAGAAGC-3′ |

| Atp11-Low | 5′GCTGCTGGGAGGTACTCAACATCAG-3′ |

| Atp11-Ver | 5′GTACTCATCGAGCACCCTTTGC-3′ |

| Atp12-Up | 5′-GTGTCCTGGCGTTTCTTAAGCTCAC-3′ |

| Atp12-Low | 5′-CACACGGAAGCTGTATCGCACTC-3′ |

| Atp12-Ver | 5′-GCTAGCTGCTGATTGACCATATCC-3′ |

| Fmc1-Up | 5′-GCTTGATACGTTTGGACAGTAGTTC-3′ |

| Fmc1-Low | 5′-TACTTCATTCTGGGATGCCTATC-3′ |

| Fmc1-Ver | 5′GCTAGTGCCAACTCGTCGTG-3′ |

| Aep1-Up | 5′-CGTAGCACTTTGTTGTTCCATGC-3′ |

| Aep1-Low | 5′-CATTTGTCGCAACGGAATTATCTG-3′ |

| Aep1-Ver | 5′-GGTTCACCCGATTTCACTGG-3′ |

| Aep1-Kl | 5′-GGGTCTTAGAAAATGATTACTACAG-3′ |

| Aep2-Up | 5′-CCTTTGTACCAAATATACTGAAG-3′ |

| Aep2-Low | 5′-CATCGTTTTAAAGTACAACTCC-3′ |

| Aep2-Ver | 5′ GCTTTACGATCCACATTCCC3′ |

| Aep2-Kl | 5′-GATTAATGTGGATAAATAGACTGG-3′ |

| Atp25-Up | 5′-CTAACCTCTCTTCTAATATACTTGC-3′ |

| Atp25-Low | 5′-GCATTCAGGTCTGAGTAATGAGC-3′ |

| Atp25-Ver | 5′-GAAATGGGGTCACAATCATCC-3′ |

| oAtp6-2 | 5′-GTATGATTCCATACTCATTTGC-3′ |

| oAtp6-4 | 5′-GCAAATGAGTATGGAATCATAC-3′ |

| o5′UTR2 | 5′-CCATCTCCATCTGTAAATCCTAC-3′ |

| o5′UTR1 | 5′-GAAGCGGGAATCCCGTAAGG-3′ |

| Verif-KanMx | 5′-GGATGTATGGGCTAAATGTACG-3′ |

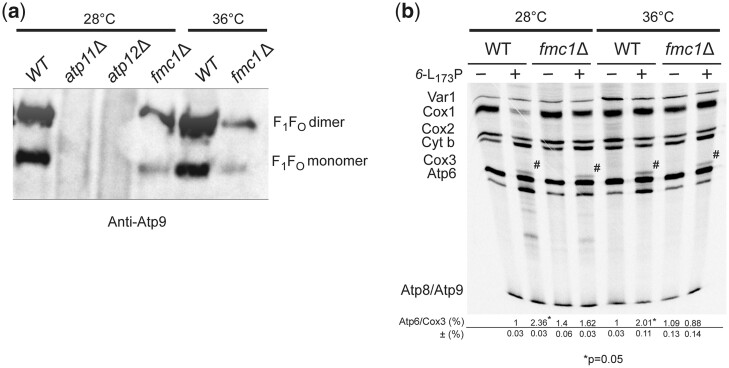

Fig. 4.

Pulse labeling of Atp6 and Cox3 and assembly of ATP synthase in strains expressing subunit 6 with and without the L173P mutation from the 5′UTR of COX2. a) Schema of mitochondrial genetic loci. As represented, the ectopic ATP6 gene, with or without the L173P mutation, is located upstream of the COX2 gene under control of the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR of COX2, in a mitochondrial genome where the coding sequence of the native ATP6 gene is replaced with ARG8m. The corresponding abbreviated genotypes (WT, 5′-UTRCOX2-ATP6WT and 5′-UTRCOX2-ATP6L173P) are indicated on the right. b) Fresh glucose cultures of the strains with the indicated genotypes were serially diluted and spotted on rich glucose and rich glycerol media. The glucose and glycerol plates were scanned after 4 and 6 days of incubation at 28°C, respectively. c) In vivo labeling of Atp6 and Cox3. Pulse labeling of Atp6 and Cox3 was performed for 20 min with [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine in the presence of cycloheximide to block cytoplasmic translation, in cells freshly grown in rich galactose medium. Total protein extracts were then prepared and separated by SDS/PAGE in a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 4 M urea and 25% glycerol. After drying of the gel under vacuum, the radiolabeled proteins were visualized using a PhosphorImager after 1-week exposure. The subunit 6 (Atp6) and Cox3 signals were quantified and compared to each other within each sample. The Atp6/Cox3 ratio was set to 1.0 for the WT. d) Steady state levels of subunit 6. Total cellular proteins samples (20 µg) extracted from the 4 analyzed strains grown in rich galactose medium were separated by SDS–PAGE in a 12% polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies against subunit 6 (Atp6) and porin. The levels of subunit 6 relative to porin are expressed in % of WT. Standard deviation and statistical significance between the 2 strains are indicated (* corresponds to a P-value <0.05) e) Protein complexes were extracted from isolated mitochondria with digitonin (2 gr/gr protein) and separated by BN-PAGE in a 3–10% polyacrylamide gel. After their transfer to a PVDF membrane, they were probed with antibodies against α-F1. The F1FO dimers and monomers, and free F1 are identified in the left-hand margin. f) In vivo labeling of Arg8 in strains RKY112 and RKY116. The rate of Arg8 synthesis in RKY112 and RKY116 from the 5′UTR of ATP6 (atp6::ARG8m) relative to Var1 was probed by pulse labeling in whole galactose grown cells for 20 min with [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine in the presence of cycloheximide to block cytoplasmic translation, with WT and RKY20 strains as controls that do not encode Arg8. Total protein extracts were then prepared and separated by SDS/PAGE in a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 4 M urea and 25% glycerol. After drying of the gel under vacuum, the radiolabeled proteins were visualized using a PhosphorImager.

Construction of plasmids encoding Aep1, Aep22, Atp25, and Atp25-Cter

The AEP1 and AEP2 genes were amplified using primer pairs Aep1-KL/Aep1-Low and Aep2-KL/Aep2-Low, respectively (Table 2) and cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega). The AEP1 and AEP2 sequences were cut off from the resulting plasmids with BamHI/PstI and XbaI/SalI, respectively, and cloned into Yep351 (Hill et al. 1986) under control of the MET25 promoter, yielding plasmids pRK54 and pRK57, respectively (the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3). The plasmid pRK56 was constructed by cloning in Yep351 the SacI–HindIII fragment encoding Atp25 in the previously described plasmid pG29ST18 (Zeng et al. 2008). The plasmid pAK13 was constructed by cloning in pRS424 (Brachmann et al. 1998) the HindIII–BamHI fragment encoding Atp25-Cter in the previously described plasmid pG29ST23 (Zeng 2008). The pAK13 was digested by NotI and BamHI and ligated with mitochondrial targeting sequence present in the previously described plasmid pYX232 (Westermann and Neupert 2000), yielding plasmid pAK19.

Table 3.

Plasmids.

| Name | Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pCM189 | 2µ, Tet-off, URA3 | Gari et al. (1997) |

| pAM19 | PaATP9-5 (ATP9-nuc) in pCM189 | Bietenhader et al. (2012) |

| pPT24 | COX2 in pBluescript-KS | Thorsness and Fox (1993) |

| pRK49 | 5′UTRCOX2-ATP6WT-3′UTRCOX2 in pPT24 | Bader et al. (2020) |

| pRK77 | 5′UTRCOX2-ATP6L173P-3′UTRCOX2 in pPT24 | This study |

| Yep351 | 2µ, LEU2 | Hill et al. (1986) |

| pRK54 | 2µ, AEP1 in Yep351 | This study |

| pRK57 | 2µ, AEP2 in Yep351 | This study |

| pG29ST32 | 2µ, ATP25-N, LEU2 | Zeng et al. (2008) |

| pG29ST23 | 2µ, ATP25-C, URA3 | Zeng et al. (2008) |

| pRK56 | 2µ, ATP25 in Yep351 | This study |

| pRS424 | 2µ, TRP1 | Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| pAK13 | ATP25-C in pRS424 | This study |

| pAK19 | ATP25-C (+mitochondrial targeting sequence) in pRS424 | This study |

In vivo labeling of mitochondrial translation products

A previously described protocol (Barrientos et al. 2002) was used to assess neo-synthesis of the mtDNA-encoded proteins in yeast cells grown to early exponential phase (107 cells/mL) in 10 mL of rich (YPGalA) or complete synthetic (CSM) galactose media. After centrifugation, the cells were washed twice with a low sulfate medium containing 2% galactose, supplemented with histidine, tryptophan, leucine, uracil, adenine, and arginine (50 mg/L each), and then incubated for 2 h at 28°C in 500 µL of the same medium (to starve the cells for endogenous cysteine and methionine). After inhibiting cytosolic protein synthesis for 5 min with 1 mM cycloheximide, 50 µCi of [35S]-methionine + [35S]-cysteine (Amersham Biosciences) was added, and the incubation was prolonged for 20 min. Total protein extracts were prepared and samples with the same level of incorporated radioactivity were separated by SDS-PAGE (Laemmli 1970) in 17.5% acrylamide gels (to separate Atp8 and Atp9) and in 12% acrylamide containing 4M urea and 25% glycerol (to separate Atp6, Cox3, Cox2, and cytochrome b). After electrophoretic migration, the gels were dried and the radioactive proteins were visualized by autoradiography using a PhosphorImager after 1-week of exposure.

Northern blot

Northern blot analysis was done as described (Rak et al. 2007b). The RNAs, extracted from whole cells grown in YPGalA, were separated in a 1% (w/v) agarose-6% (v/v) formaldehyde gel in MOPS buffer (20 mM MOPS, 5 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA), and then transferred to a Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) and hybridized with DNA probes specific to ATP9 (a PCR product amplified from MR6 DNA with primers 5′-AATAAGATATATAAATAAGTCC and 5′-GAATGTTATTAATTTAATCAAATGAG) and 21S RNA (a PCR product amplified with primers 21S.1: 5′-GTATAAGGTGTGAACTCTGCTCCAT and 21S.2: 5′-GGGGAGACAGTTGTTGTATCATTAC). The ATP9 and 21S RNA probes were labeled with [α-32P]-dCTP using the Prime-a-Gene Labelling System kit from Promega and purified on MicroSpin G-25 columns from Amersham Biosciences. Hybridizations were carried out in 50% (v/v) formamide, 5× SSPE, 0.5% SDS, 7% polyethylene glycol 5000, 5× Denhardt’s solution, 100 µg/mL carrier DNA at 42°C.

BN- and SDS-PAGE

Mitochondria were isolated from yeast cells grown until middle exponential phase (2–3 × 107 cells/mL) in rich galactose medium (YPGalA) at 28°C using the previously described enzymatic method (Guérin et al. 1979). Protein concentration was determined according to (Lowry et al. 1951) in the presence of 5% SDS. Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) was done as described in (Schagger and von Jagow 1991). Briefly, a sample of mitochondria containing 200 µg of proteins was suspended in 100 µL of 30 mM HEPES, 150 mM potassium acetate, 12% glycerol, 2 mM 6-aminocaproic acid, 1 mM EGTA, 2% digitonin (from Sigma) buffered at pH 7.4 and supplemented with an inhibitor cocktail tablet (from Roche). After 30 min of incubation on ice, the extract was cleared by centrifugation (18,600 g, 4°C, 30 min), supplemented with 4.5 µL of loading dye (5% Serva Blue G-250, 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid), and run in NativePAGETM 3-12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen). The proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and probed with 1:5,000 diluted polyclonal antibodies against Atp6/subunit a, Atp1/subunit α, and Atp9/subunit c (a gift from J. Velours). The tested proteins were revealed using peroxidase-labeled antibodies (Promega) at a 1:5,000 dilution and the ECL reagent of Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific). SDS-PAGE analysis and immunological detection of proteins from isolated mitochondria or whole cells was performed as previously described (Schagger and von Jagow 1991). The open source program Image J (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) was used to quantify the immunological signals and statistical significance between samples was evaluated using Student’s t-test.

Results

Regulation of ATP6

Translation of assembly-defective subunit 6 variants is upregulated

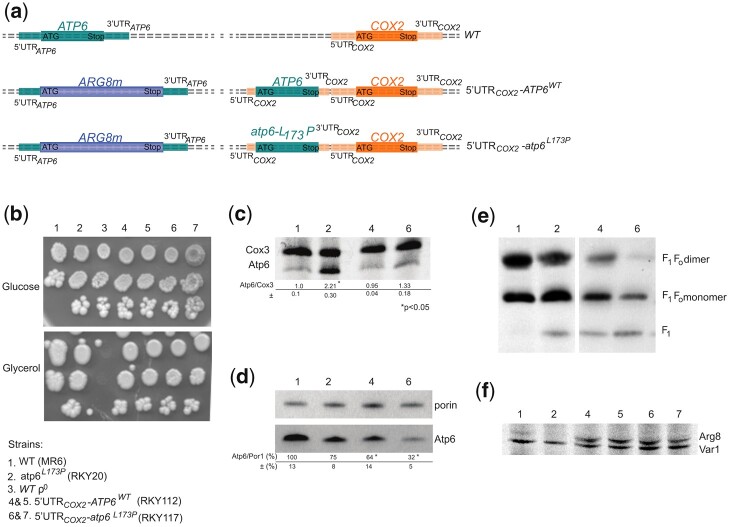

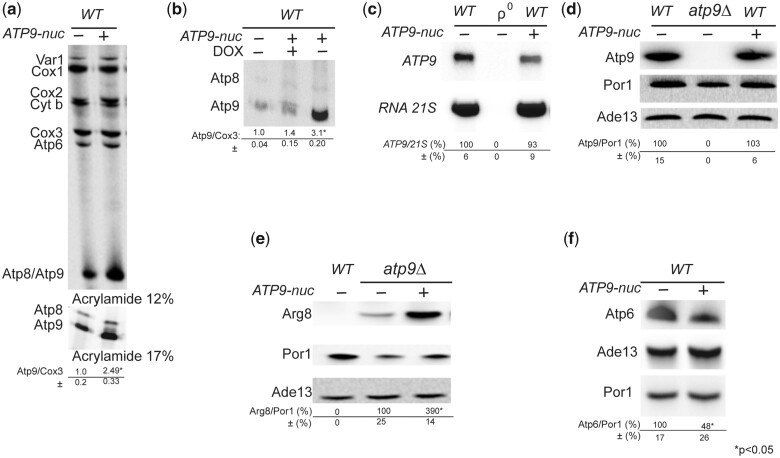

In previous work, we observed that an assembly-defective mutant version of subunit 6 harboring a leucine-to-proline change at position 173 (L173P) in mature subunit 6 (which is produced after cleavage of the 10 N-terminal residues present in the precursor protein) was translated at a rate that was 2–3-fold faster than the wild-type protein [(Kucharczyk et al. 2009a); see below]. To ascertain that the L173P change was responsible for this effect, mitochondrial translation was herein investigated in 8 genetically independent recombinant 6-L173P clones issued from crosses between RKY12 (a synthetic ρ– with the 6-L173P mutation, see Table 1) and MR10 [a ρ+ strain in which the coding sequence of ATP6 is replaced with ARG8m (atp6::ARG8m), see Table 1], in comparison to 8 genetically independent WT recombinant clones issued from crosses between SDC30 (a synthetic ρ– containing the wild-type ATP6 gene, see Table 1) and MR10. Owing to the presence in RKY12 and SDC30 of the nuclear karyogamy delaying kar1-1 mutation, it was possible to isolate the mitochondrial DNA recombinants in MR10 haploid background (which is the one of WT strain MR6). As a result, the 16 clones are isogenic except for the L173P mutation. Mitochondrial translation in these 16 clones was conducted with whole cells in the presence of cycloheximide (to block cytosolic translation) during a rather short time (20 min) after the addition of a mixture of radioactively labeled [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine, a procedure widely used to evaluate the rate of synthesis of the mitochondrial translation products. As shown in Fig. 1a, subunit 6 was upregulated in the 8 L173P clones vs. the 8 reconstructed WT clones, which demonstrates that no other change in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA was involved in the increased rate of subunit 6 synthesis in the L173P clones. Two other subunit 6 variants, L173R (Rak et al. 2007a) and W126R (Kucharczyk et al. 2013), which assemble normally but are compromised functionally, were translated at the normal rate. In an effort to explain these findings, we investigated by pulse labeling the translation efficiency for 5 additional subunit 6 variants, harboring either single- or double-point mutations. We observed accelerated translation for 1 subunit 6 variant, while the 4 others were synthesized at the normal rate (Fig. 1b). Remarkably, in related work, we found that the strain showing enhanced subunit 6 synthesis was the only subunit 6 variant from this group of 5 that showed an assembly defect (Kucharczyk et al. 2019). Hence, it would appear that yeast accelerates the rate of subunit 6 translation when assembly of the ATP synthase stalls at the point where subunit 6 should be incorporated to complete the enzyme’s proton channel.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial translation in various subunit 6 mutants. a) The influence of the subunit 6 (Atp6) L173P variant on mitochondrial translation was investigated in 8 genetically independent recombinant 6-L173P clones issued from crosses between RKY12 (a synthetic ρ– with the 6-L173P mutation) and MR10 [a ρ+ strain in which the coding sequence of ATP6 is replaced with ARG8m (atp6::ARG8m)], in comparison to 8 genetically independent WT recombinant clones issued from crosses between SDC30 (a synthetic ρ– containing the wild-type ATP6 gene) and MR10 (see Table 1 for strain genotypes). b) Mitochondrial translation in 5 other subunit 6 mutants. Labeling of the mitochondrial translation products was performed in galactose grown cells during 20 min in the presence of [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine and cycloheximide to block cytoplasmic translation. Total cellular protein extracts were then prepared and separated by SDS/PAGE in a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 4 M urea and 25% glycerol. The gels were dried and the radiolabeled proteins were visualized using a PhosphorImager after 1-week exposure. The subunit 6 (Atp6) and Cox3 signals were quantified and compared to each other within each sample. The Atp6/Cox3 ratio was set to 1 for the WT.

What is the mechanism behind accelerated synthesis of assembly-defective subunit 6?

There is solid evidence in the literature that supports a model for ATP synthase biogenesis in which subunit 6 does not get incorporated until late in the process (Tzagoloff et al. 2004; Rak et al. 2007b). Hence, it was deemed logical to investigate some of the structural elements that would already be in place in the partially assembled enzyme for actions that promote enhanced expression of assembly-defective subunit 6 variants. This investigation was conducted with strains where the subunit 6 L173P mutation was combined to genetic modifications leading to defects in the assembly of the F1 or the 910-ring, and we also tested the requirement for the 5′-UTR of ATP6 by ectopically expressing the subunit 6 variant L173P from the 5′-UTR of COX2.

The F1

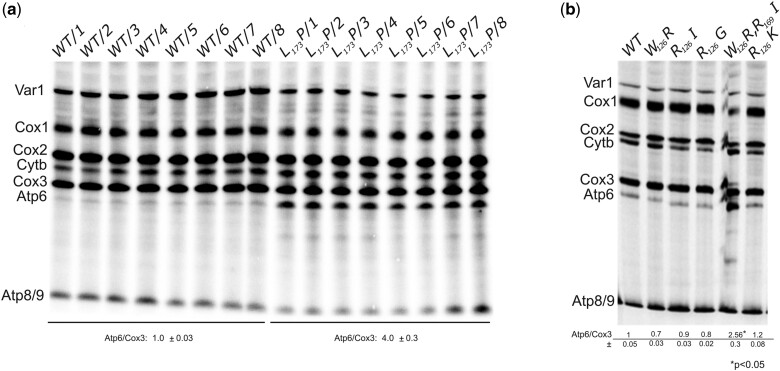

The importance of the F1 in the upregulation of the assembly-defective subunit 6 variant L173P was tested using the conditional strain fmc1Δ. This strain has a diminished capacity to assemble the F1 especially when grown at 36°C (5–10% vs. WT), whereas quite good levels of F1 accumulated in fmc1Δ cells grown at 28°C [(Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2001), Fig. 2a]. At both temperatures, the strain fmc1Δ normally synthesizes the subunit 6 as well as the other proteins encoded by the mitochondrial DNA (Fig. 2b). The synthesis of the subunit 6 variant L173P was still stimulated in strain fmc1Δ grown at 28°C, although less efficiently than in a WT nuclear background, whereas the upregulation of subunit 6 was totally lost at 36°C. Hence, it appears that the mechanism responsible for the translation stimulation of the assembly-defective 6-L173P variant is dependent on F1.

Fig. 2.

Upregulation of the subunit 6-L173P variant is F1-dependent. a) ATP synthase in BN-gels. Mitochondria were isolated from the indicated strains grown in rich galactose at the indicated temperature. Proteins were extracted with digitonin (2 gr/gr protein) and separated by BN-PAGE on a 3–10% polyacrylamide gel (50 µg/lane). The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with antibodies against subunit 9. The F1–FO monomers and dimers are identified on the right. b) Cells from WT and fmc1Δ yeasts with or without the subunit 6 mutation L173P were grown in rich galactose at 28°C or 36°C, as indicated, and then incubated for 20 min with [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine in the presence of cycloheximide to block cytoplasmic translation. Total cellular protein extracts were then prepared and separated by SDS/PAGE in a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 4 M urea and 25% glycerol (with a 30:0.8 ratio of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide). The gels were dried and the radiolabeled proteins were visualized using a PhosphorImager. The subunit 6 (Atp6) and Cox3 signals were quantified and compared to each other within each sample. The Atp6/Cox3 ratio was set to 1.0 for the WT. The identity of the band above Cox3 (designated by a hash sign) in the samples containing the subunit 6 variant L173P is unknown.

The gel of Fig. 2b shows a band of unknown identity (designated by a hash sign) above Cox3 in samples containing the subunit 6 variant L173P. As described below, it was detected in other experiments in which this mutant was used, and with a yeast strain lacking the ATP6 gene (atp6Δ), indicating that this extra polypeptide was not some aberrant translation product derived from the modified atp6 loci.

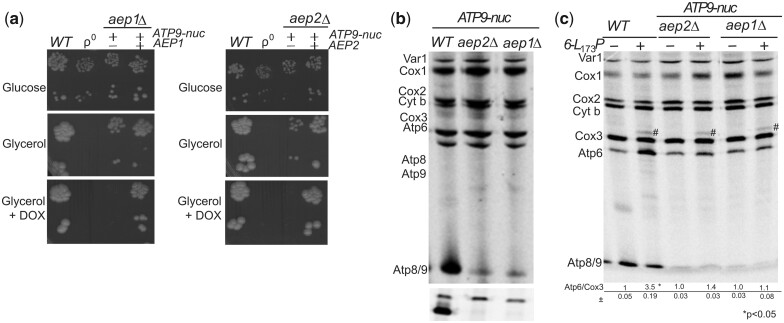

Subunit 9

Yeast cells lacking the subunit 9 have a high propensity to lose the mitochondrial genome (Bietenhader et al. 2012), which makes it difficult to evaluate the importance of this protein in the upregulation of assembly-defective subunit 6. To overcome this difficulty, we used aep1Δ and aep2Δ strains unable to synthesize subunit 9 and a previously characterized nuclear ATP9 gene present in P. anserina [PaAtp9-5 (Déquard-Chablat et al. 2011), here referred to as ATP9-nuc]. Although the protein product of ATP9-nuc (Atp9-nuc) shows a number of primary sequence differences with yeast subunit 9, a yeast strain lacking the native mitochondrial ATP9 gene (atp9Δ) had the ability to grow slowly on nonfermentable carbon sources upon transformation with a plasmid harboring ATP9-nuc (Bietenhader et al. 2012), showing that Atp9-nuc can assemble and function within the yeast ATP synthase albeit much less efficiently than subunit 9. That Atp9-nuc only partially compensates for the absence of subunit 9 is not very surprising considering that S. cerevisiae is not optimized for ATP synthase biogenesis with a nucleus-encoded version of this protein that must be imported into mitochondria post-translationally, routed to the inner membrane, and assembled with the other yeast ATP synthase subunits. As expected, Atp9-nuc enabled aep1Δ and aep2Δ strains to grow slowly from respiratory carbon sources and when expression of Atp9-nuc was inhibited with doxycycline, they did not show any respiratory growth (Fig. 3a). The subunit 9 was not detected by pulse labeling in these 2 strains while the other proteins encoded by the mitochondrial DNA were all effectively synthesized (Fig. 3b). Importantly, although the FO assembles poorly with Atp9-nuc, the F1 forms and accumulates efficiently (Bietenhader et al. 2012), which permitted us to evaluate the importance of the membrane motor of ATP synthase in the upregulation of the subunit 6 variant L173P without any interference due to a lack in F1. As shown in Fig. 3c, the L173P substitution did not stimulate subunit 6 synthesis in aep1Δ and aep2Δ mutants expressing Atp9-nuc indicating that subunit 9, like the F1, is required for upregulating subunit 6 in response to mutations in this protein that compromise its assembly.

Fig. 3.

Upregulation of the subunit 6 variant L173P is subunit 9-dependent. a) Growth phenotypes. Fresh glucose cultures of the indicated strains were serially diluted and spotted on rich glucose and glycerol media with or without 5 µg/mL doxycycline (DOX) as indicated. The glucose and glycerol plates were scanned after 3 and 6 days of incubation at 28°C, respectively. b and c) In vivo labeling of mitochondrial translation products. Pulse labeling was performed for 20 min with [35S]-methionine + [35S]-cysteine in the presence of cycloheximide to block cytoplasmic translation, in cells freshly grown in rich galactose medium. Total protein extracts were then prepared and separated by SDS/PAGE in 2 different gels: (1) 12% polyacrylamide containing 4 M urea and 25% glycerol (to resolve Var1, Cox1, Cox2, Cytochrome b, Cox3, and Atp6); (2) 17.5% of polyacrylamide (to resolve Atp8 and Atp9). The 2 gels shown in b) were loaded with equal amounts of radioactivity from the same experiment. After drying of the gels under vacuum, the radiolabeled proteins were visualized using a PhosphorImager after one-week of exposure. The subunit 6 (Atp6) and Cox3 signals were quantified and compared to each other within each sample. The Atp6/Cox3 ratio was set to 1.0 for the WT. The identity of the band above Cox3 (designated by a hash sign) in the samples containing the 6-L173P variant is unknown.

The 5′-UTR of the ATP6 mRNA

Expression of each yeast mitochondrial gene involves a peculiar 5′-UTR and specific translational activator protein(s) (Fox 2012; Herrmann et al. 2013; Ott et al. 2016). To test the implication of the 5′-UTR of ATP6 in the upregulation of the assembly-defective subunit 6 variant L173P, we ectopically expressed ATP6 with or without the L173P mutation from the 5′-UTR of COX2 in a strain where the native ATP6 gene is in-frame replaced with ARG8m (Rak et al. 2007b) (Fig. 4a). In the resulting strains (5′UTRCOX2-ATP6WT and 5′UTRCOX2-atp6L173P), subunit 6 translation is activated by Pet111 (the translation activator of COX2) instead of Atp22 (the translation activator of ATP6). Both strains grew well on glycerol (Fig. 4b) and synthesized subunit 6 as effectively as in WT yeast (Fig. 4c), which indicated that the 5′-UTR of the ATP6 mRNA is needed for stimulating translation of the subunit 6 variant L173P. Interestingly, despite a good rate of synthesis the ectopically expressed subunit 6 without the L173P mutation (5′UTRCOX2-ATP6WT) was about 2 times less abundant at the steady-state than in WT cells expressing subunit 6 from its own 5′-UTR (Fig. 4d). While BN-PAGE analyses revealed only fully assembled ATP synthase dimers and monomers in mitochondria from the WT, those from the 5′UTRCOX2-ATP6WT strain additionally contain free F1 particles (Fig. 4e). The presence of free F1 is typically observed in strains where subunit 6 fails to assemble properly (Rak et al. 2007b), and it can therefore be inferred that the assembly of subunit 6 was less efficient when it was expressed from the 5′-UTR of COX2 instead of its native 5′-UTR. Not surprisingly, a further decrease in the levels of subunit 6 was observed with the ectopic atp6-L173P gene (Fig. 4e), reflecting the deleterious consequences by its own of the leucine-to-proline change on the incorporation of subunit 6 into ATP synthase.

Both ectopic strains (5′UTRCOX2-ATP6WT and 5′UTRCOX2-atp6L173P) express Arg8 from the 5′ UTR of ATP6 (Fig. 4a). As they are both deficient in the incorporation of subunit 6 into ATP synthase it was expected that Arg8 should be synthesized similarly in the 2 strains. This was indeed observed (Fig. 4f).

Regulation of ATP9

Translation of subunit 9 is stimulated by ATP9-nuc and a lack in subunit 6

Because of the primary sequence differences between the fungal Atp9-nuc and yeast subunit 9 proteins (Déquard-Chablat et al. 2011) and the poor capacity of Atp9-nuc to support the assembly of a functional ATP synthase in yeast cells lacking subunit 9 (Bietenhader et al. 2012), we reasoned that expressing Atp9-nuc in wild-type yeast could influence translation and/or assembly of the yeast subunit 9 protein. In support of this hypothesis, co-expressing Atp9-nuc and subunit 9 resulted in an accelerated rate of subunit 9 synthesis, whereas that of the other mitochondrial gene products was unaffected (Fig. 5a). This effect was lost when expression of the plasmid-borne fungal gene was inhibited with doxycycline (Fig. 5b), which demonstrated that Atp9-nuc was truly responsible for the increased rate of subunit 9 synthesis. The steady state levels of ATP9 mRNA and its protein product were identical in untransformed WT and WT cells transformed with the Atp9-nuc gene (Fig. 5c and d). Cumulatively, these results showed that effect from Atp9-nuc was on translation, not transcription, and that the accelerated translation of subunit 9 did not lead to a stable accumulation of the overexpressed protein. One could hypothesize that the enhanced labeling of subunit 9 in WT expressing ATP9-nuc resulted from interactions with Atp9-nuc that stabilize subunit 9 and not from a higher rate of translation. At odds with this, the expression of Arg8 from the atp9∷ARG8m locus in atp9Δ yeast (in which the subunit 9 is thus absent) was also considerably stimulated by Atp9-nuc (Fig. 5e), which definitely demonstrates that the higher labeling of subunit 9 in WT yeast expressing Atp9-nuc was caused by a faster rate of synthesis of this protein.

Fig. 5.

ATP9-nuc stimulates translation at the mitochondrial ATP9 locus. a) Influence of ATP9-nuc on the translation of mitochondrial gene products in WT yeast. Pulse labeling was performed in cells freshly grown in rich galactose medium for 20 min with [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine in the presence of cycloheximide to block cytoplasmic translation. Total cellular proteins were then extracted and separated by SDS/PAGE in 2 different gels: (1) 12% polyacrylamide containing 4 M urea and 25% glycerol (to resolve Var1, Cox1, Cox2, Cytochrome b, Cox3, and Atp6); (2) 17.5% polyacrylamide (to resolve Atp8 and Atp9). The 2 gels were loaded with equal amounts of radioactivity from the same experiment. After drying of the gels under vacuum, the radiolabeled proteins were visualized using a PhosphorImager. The subunit 9 (Atp6) and Cox3 signals were quantified and compared to each other within each sample. The Atp9/Cox3 ratio was set to 1.0 for the WT. Standard deviation and statistical significance of the differences between strains is indicated (* corresponds to a P-value <0.05). b) Evaluation of subunit 9 synthesis in WT yeast after blocking expression of ATP9-nuc with 5 µg/mL doxycycline (DOX), using the same procedure as in a). c) Northern blot analyses. Total RNAs isolated from cells with the indicated genotypes (ρ0 is a derivative of the WT strain totally devoid of mtDNA) freshly grown in rich galactose medium were separated in a 1% agarose gel. After their transfer to a Nytran membrane, the RNAs were hybridized with 32P labeled DNA probes specific to ATP9 and 21S RNA. The ATP9 mRNA signals were normalized to those corresponding to 21S RNA. d–f) Steady state levels of proteins in cells. Total proteins extracted from cells with the indicated genotypes grown in rich galactose medium were separated by SDS–PAGE (20 µg/lane), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with antibodies against the indicated proteins. The levels of subunits 6 (Atp6), 9 (Atp9), and Arg8 (expressed from atp9∷ARG8m) are normalized to porin. Ade13 is used as a cytosolic protein marker. The symbol “*” indicates a statistically significant difference between samples (P-value <0.05).

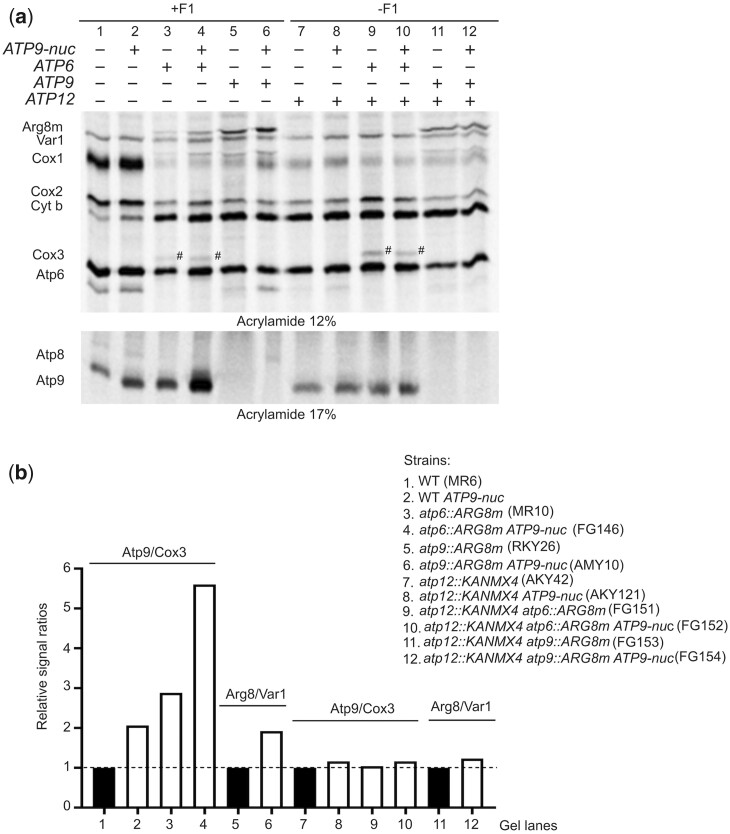

While subunit 6 was synthesized normally in WT cells expressing the fungal gene for Atp9-nuc (Fig. 5a), the steady state levels of subunit 6 were diminished by about 50% relative to untransformed WT (Fig. 5f). In view of the fact that unassembled subunit 6 is highly susceptible to proteolytic degradation (Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2001; Kucharczyk et al. 2009b; Rak et al. 2009; Godard et al. 2011; Kabala et al. 2014; Su et al. 2020), the lack of subunit 6 induced by Atp9-nuc suggested that Atp9-nuc results in ATP synthase formation defects (see below for a possible explanation). Possibly, the lack in subunit 6 was responsible for, or contributed to the stimulation of subunit 9 translation. Indeed, subunit 9 translation was found stimulated in a strain lacking the ATP6 gene (atp6Δ) [(Rak et al. 2007b), see also Fig. 6a, lane 3 and b). However, transforming atp6Δ yeast with Atp9-nuc resulted in a much higher (5.6-fold) stimulation of subunit 9 synthesis (Fig. 6a, lane 4), indicating that the partial lack in subunit 6 in WT cells expressing Atp9-nuc was not alone responsible for the enhanced rate of subunit 9 translation.

Fig. 6.

Upregulation of the mitochondrial ATP9 locus by ATP9-nuc and/or a lack in Atp6 is F1-dependent. a) Cells with the indicated genotypes were grown in rich galactose medium and their mitochondrially encoded proteins were radioactively labeled for 20 min with [35S]-methionine and [35S]-cysteine in the presence of cycloheximide to inhibit cytosolic translation. Total protein extracts were then prepared and resolved by SDS/PAGE in 2 types of gel loaded with the same amount of radioactivity (as in Fig. 2). After drying of the gels, the proteins were using a PhosphoImager. b) Quantification of subunit 9 and Arg8 expressed from the ATP9 locus (atp9∷ARG8m). The levels of subunit 9 and Cox3 in each sample were quantified and compared to each other. Those in lanes 1–4 are compared to each other after setting to 1.0 the Atp9/Cox3 ratio lane 1. Those in lanes 7–10 are compared to each other after setting to 1.0 the Atp9/Cox3 ratio in lane 7. The levels of Arg8 and Var1 were quantified in lanes 5, 6, 11, 12. The Arg8/Var1 ratio in lane 5 was set to 1.0 and compared to the one in lane 6. The Arg8/Var1 ratio in lane 11 was set to 1.0 and compared to the one in lane 12.

Upregulation of ATP9 induced by ATP9-nuc and/or a lack in subunit 6 is F1-dependent

The rate of subunit 9 synthesis was found unaffected in strains lacking the α or β subunit of F1 or unable to assemble these proteins due to the absence of Atp11 or Atp12, indicating that the F1 does not influence subunit 9 synthesis (Rak et al. 2009, 2011). However, in the absence of Atp12, subunit 9 synthesis was no longer upregulated in strains expressing ATP9-nuc and/or lacking subunit 6 (Fig. 6a, lanes 2, 3, 4 vs. 8, 9, 10, respectively, and b), indicating that expression of subunit 9 is not F1-independent. The F1-dependency of the ATP9 locus expression is further supported by the enhanced labeling of Arg8 from the atp9∷ARG8m allele (atp9Δ) in the presence of ATP9-nuc (Figs. 5e and 6a, lanes 5 vs. 6, and b) and the loss of this effect when the ATP12 gene was deleted (Fig. 6a, lanes 11 vs. 12, and b). Another interesting observation is the much higher labeling of Arg8 in atp9Δ vs. atp6Δ yeasts (Fig. 6a, lanes 3 vs. 5), which is not very surprising due to the presence of 10 subunits 9 for 1 subunit 6 in ATP synthase.

The poor labeling of Cox1 in lanes 3–12 results from the lack of functional ATP synthase. This effect was observed in yeast ATP synthase defective mutants as long as there are no proton leaks through the FO (Duvezin-Caubet et al. 2003; Rak et al. 2007a, 2007b; Kucharczyk et al. 2009a, 2009b, 2010), which is the case in all the mutant strains with a reduced Cox1 labeling in Fig. 6. Based on these observations, it has been argued that the biogenesis of complex IV is modulated by the activity of FO (Su et al. 2019).

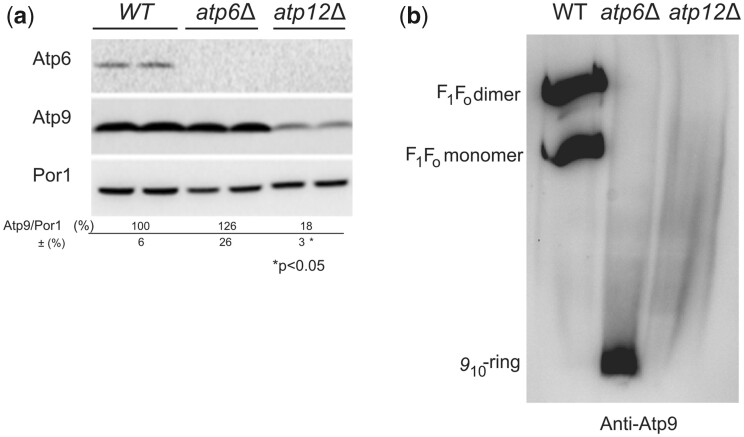

Subunit 9 is more susceptible to degradation and fails to assemble in the absence of F1

Despite a good rate of synthesis (Fig. 6a, lanes 1 vs. 7), the steady levels of subunit 9 were diminished by about 80% in atp12Δ vs. WT (Fig. 7a) and the residual subunit 9 proteins were not detected as oligomeric rings in BN gels as they were in atp6Δ yeast (Fig. 7b). These observations suggest that formation/stability of the subunit 9-ring is F1-dependent (see below).

Fig. 7.

Influence of a lack in Atp12 or subunit 6 on the steady state levels and assembly of subunit 9. a) Steady states levels of subunit 9 in atp12Δ and atp6Δ yeasts. Total protein extracts from WT, atp6Δ, and atp12Δ strains grown in rich galactose medium were prepared and separated by SDS–PAGE in a 12% polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with antibody against subunit 6 (Atp6), subunit 9 (Atp9), and porin (Por1). The reported values (expressed as %WT) were calculated from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance of the differences between samples is indicated. b) Assembly of subunit 9 in atp12Δ and atp6Δ yeasts. Mitochondria were isolated from WT, atp6Δ, and atp12Δ strains grown in rich galactose medium. Digitonin extracts containing the same quantity of proteins (50 µg) were prepared and separated in 3–10% polyacrylamide BN gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with antibodies against subunit 9. The F1–FO monomers and dimers, and subunit 9-ring are identified in the left-hand margin.

Discussion

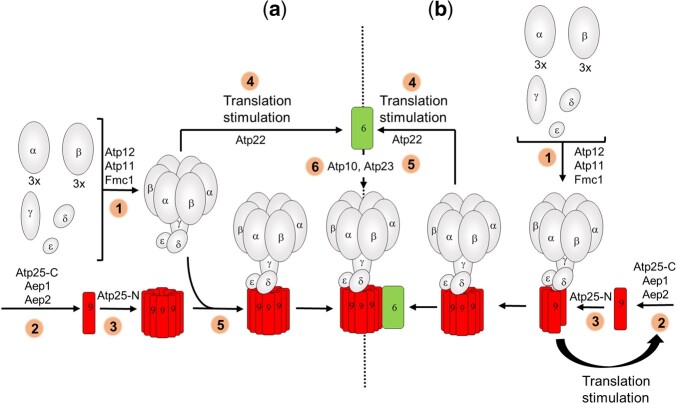

There is solid evidence in the literature supporting a model in which ATP synthase formation starts with the assembly of F1 followed by association with the subunit 9-ring (910-ring) and peripheral stalk subunits, and finally incorporation of subunit 6, in a process that involves a number of helper proteins with specific actions (Tzagoloff et al. 2004; Ackerman and Tzagoloff 2005; Rak et al. 2007b; Kucharczyk et al. 2008; Rak et al. 2009). In contrast, very few studies have so far been devoted to the mechanisms allowing the ATP synthase subunits to be produced in the good stoichiometry from 2 cell compartments (the cytosol and the mitochondrial matrix), an issue we have addressed in the present study.

It has been reported that translation of subunits 6 and 8 is largely inhibited in strains with a virtual absence of F1 due to genetic ablation of α-F1 or β-F1 or 1 of 2 proteins (Atp11 and Atp12) that associate them to each other while the synthesis of subunit 9 is unaffected by the loss of F1 (Rak et al. 2009, 2011). On this basis, it was suggested that the F1 is the sole component of ATP synthase involved in the activation/stimulation of subunits 6 and 8 synthesis (by Atp22), and that the 910-ring forms separately, independently of any other ATP synthase component (Fig. 8a). This view is challenged by the present study.

Fig. 8.

Model of assembly-dependent translation of subunits 6 and 9 of yeast ATP synthase. a) Previously reported model (Rak et al. 2009, 2011). 1: The subunits of F1 (α, β, γ, δ, ε) assemble with the help of Atp11, Atp12, and Fmc1. 2 and 3: The subunit 9 is produced and assembled with the help of Aep1, Aep2, Atp25-C, and Atp25-N independently of any other ATP synthase component. 4: The F1 alone is involved in the activation of subunit 6 translation by Atp22. 5: The F1 and the 910-ring associate to each other. 5: The subunit 6 with the help of Atp10 and Atp23 is incorporated into ATP synthase. b) Model based on the results reported in this study. 1: The subunits of F1 (α, β, γ, δ, ε) assemble with the help of Atp11, Atp12 and Fmc1. 2, 3: The synthesis and assembly of subunit 9 with the help of Aep1, Aep2, Atp25-C, and Atp25-N is F1-dependent. 4: The F1-910 intermediate stimulates translation of subunit 6 by Atp22. 5: The subunit 6 with the help of Atp10 and Atp23 is incorporated into ATP synthase. The peripheral stalk subunits 8, 4, i, j, f, d, and OSCP of the ATP synthase monomer are not represented.

We provide evidence that both the F1 and the 910-ring influence the synthesis of subunit 6. Indeed, point mutations in this protein that partially compromise its assembly result in the acceleration of the rate of subunit 6 synthesis (Fig. 1), and this effect was lost in strains with a diminished capacity to assemble the F1 (Fig. 2) or the 910-ring (Fig. 3C), and in a strain expressing subunit 6 from the 5′UTR of the COX2 gene (Fig. 4). These data suggest the existence of an assembly-dependent regulatory loop in which functional interaction of Atp22 [the translational activator of subunit 6 (Zeng et al. 2007a)] with the 5′-UTR of the ATP6 mRNA involves both the F1 and the 910-ring rather than F1 alone as was previously proposed (Rak et al. 2009, 2011) (Fig. 8B).

Interestingly, while wild-type subunit 6 was efficiently synthesized from the 5′-UTR of COX2 (Fig. 4c), there was at the steady state about 50% less subunit 6 than in wild-type yeast (Fig. 4d) and defects in ATP synthase were observed as evidenced by the presence of free F1 in mitochondrial samples resolved by BN-PAGE (Fig. 4e). Possibly, when not produced from its native 5′-UTR, nascent subunit 6 interacts less efficiently with Atp10 and Atp23 [2 proteins specifically required to incorporate subunit 6 into ATP synthase (Ackerman and Tzagoloff 1990a; Osman et al. 2007; Zeng et al. 2007c), and this reduces the yield in assembly. This conclusion is in line with previous studies that have revealed the importance of 5′-UTRs in post-translational biogenesis of other yeast mtDNA-encoded proteins (Sanchirico et al. 1998; Gruschke and Ott 2010; Gruschke et al. 2012).

Somewhat intriguingly, while translation of subunits 6 and 8 is largely inhibited in strains with a virtual absence of F1 (Rak et al. 2009, 2011), it is fully preserved with a 90% drop in F1 in yeast cells lacking a protein (Fmc1) that stabilizes Atp12 at 36°C [(Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2001), Fig. 2]. The present study provides an explanation for these observations. Indeed, Atp22 was barely detectable in atp11Δ and atp12Δ mitochondria, whereas it accumulates well in those from fmc1Δ yeast grown at 36°C (Supplementary Fig. 1). The block in subunit 6 synthesis in strains totally lacking the F1 is thus probably due to the absence of Atp22 in mitochondria. Consistently, subunit 6 synthesis was fully recovered in these strains upon transformation with a high copy number plasmid harboring ATP22 (Rak and Tzagoloff 2009). The lack of Atp22 in atp11Δ and atp12Δ mitochondria might result from the extremely detrimental consequences of a total or virtual lack in F1. Indeed, these mitochondria have a very poor content in complexes III and IV (Ebner and Schatz 1973), are very unstable genetically (Ebner and Schatz 1973), energize very poorly the inner membrane (Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2003), and show severe defects in protein import (Yuan and Douglas 1992), whereas mitochondria from fmc1Δ cells grown at 36°C are much less affected (Lefebvre-Legendre et al. 2001) and do not show defects in protein import (Aiyar et al. 2014). Thus, major mitochondrial damage rather than disruption of a specific F1-dependent regulatory mechanism seems responsible for the lack of subunits 6 and 8 synthesis in yeast cells totally devoid of F1.

In revealing that subunit 6 synthesis is modulated by both the F1 and the 910-ring, our study describes a novel paradigm for the regulation of subunit 6 in which the F1–910 subcomplex rather than the F1 alone modulates the synthesis of this protein. This model is in line with the concept of assembly-dependent regulation loop developed for cytochrome b and Cox1 according to which the synthesis of these proteins is stimulated by their direct protein partners (the F1 is not a direct partner of subunit 6). As the subunit 6 is incorporated after formation of the F1-910 intermediate, in all the models thus far proposed (Tzagoloff et al. 2004; Ackerman and Tzagoloff 2005; Rak et al. 2007b, 2009; Kucharczyk et al. 2008), it makes more sense that this intermediate rather than the F1 alone signals the need for producing subunit 6 as a means to couple the synthesis of this protein to its assembly.

Unlike previous studies (Rak et al. 2009, 2011), we conclude that the subunit 9 is also part of an assembly-dependent regulatory loop. A first clue was the higher pulse labeling of subunit 9 without any change in the levels of the ATP9 mRNA in WT yeast transformed with a nuclear ATP9 (PaAtp9-5) gene from P. anserina (Déquard-Chablat et al. 2011), here referred to as ATP9-nuc, and the loss of this effect after genetic ablation of F1 (Figs. 5 and 6). As ATP9-nuc also stimulated expression of Arg8 in a strain where the coding sequence of ATP9 was replaced with ARG8m (Figs. 5e and 6a, lanes 3 and 5, and Fig. 6b), it is evident that ATP9-nuc stimulated the rate of translation at the ATP9 locus whether the subunit 9 was or not present.

The ability of Atp9-nuc to partially restore the capacity of atp9Δ cells to grow in respiratory media shows that it can interact and function within yeast ATP synthase, albeit less efficiently than subunit 9 (Bietenhader et al. 2012). In the absence of Atp25-Nter, a polypeptide required for assembling the 910-ring (Zeng et al. 2008), the compensation of atp9Δ yeast by Atp9-nuc is less efficient (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that Atp9-nuc can functionally interact with Atp25-Nter. As a result of the interactions between Atp9-nuc and Atp25-Nter, there is less Atp25-Nter available for the assembly of the 910-ring. This may be responsible for the reduced content of subunit 6 in WT expressing Atp9-nuc (50% vs. WT) despite a normal rate of synthesis of this protein. Indeed, when it cannot interact properly with its protein partners, the subunit 6 becomes highly susceptible to proteolytic degradation (Ackerman and Tzagoloff 1990a; Zeng et al. 2007b, 2008; Kucharczyk et al. 2009b; Godard et al. 2011). There is thus no doubt that expressing Atp9-nuc in WT yeast results in defects in the assembly of ATP synthase, and this is what possibly causes the upregulation of subunit 9. Indeed, it is a reasonable assumption that the 910-ring forms progressively with the addition one by one of subunit 9 monomers and newly synthesized subunit 9 is provided until completion of the ring. In the presence of Atp9-nuc, incomplete subunit 9 oligomers will be more abundant and in response, subunit 9 is synthesized more rapidly. The enhanced rate of subunit 9 translation observed in the absence of subunit 6 [3–4× in atp6Δ yeast; 5.6× in atp6Δ yeast expressing Atp9-nuc (Fig. 6)] may be explained similarly. Indeed, when not wedged between the F1 and subunit 6, the 910-ring is certainly less stable and dissociates more frequently.

Another interesting finding here reported is the high susceptibly to degradation of unassembled subunit 9, either when it is produced in excess (in WT + Atp9-nuc, Fig. 5) or when the F1 is absent (in atp12Δ yeast, Fig. 7a). The residual subunit 9 polypeptides in atp12Δ yeast (20% vs. WT) could not be detected as oligomers in BN-gels (Fig. 7b), and newly assembled 910-ring could not be detected after pulse labeling in mitochondria isolated from a strain lacking the F1 (Rak et al. 2011). These observations indicate that the subunit 9 cannot assemble in the absence of F1. It has been proposed that the entire process of yeast mitochondrial gene expression occurs within large platforms called MIOREX that interact with the mitochondrial ribosome and proteins that help the assembly of the OXPHOS complexes (including those involved in subunit 9 biogenesis) (Kehrein et al. 2015a, 2015b). It is tempting from the data here reported to speculate that newly formed F1 interacts with this platform to facilitate co-translational insertion of subunit 9 within ATP synthase (Fig. 8b).

The present study reveals that the synthesis of subunits 6 and 9 is coupled to the incorporation of these proteins into ATP synthase by mechanisms similar to those involved in the regulation of complexes III and IV biogenesis. In addition to increasing the yield in assembly of these 2 proteins, these regulations are likely important to prevent accumulation of free FO and F1 particles that can dissipate the mitochondrial membrane electrical potential and the main source of chemical energy of the cell.

Data availability

Strains and plasmids are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, and tables.

Supplemental material is available at GENETICS online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (5R01GM111873-02) to LMS and J-PdR, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-09-BLAN-00500) to J-PdR, and (ANR-10-IDEX-0002) to HB and the National Science Centre of Poland (UMO-2011/01/B/NZ1/03492) to RK.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Anna M Kabala, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France; Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 01-224 Warsaw, Poland.

Krystyna Binko, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France; Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 01-224 Warsaw, Poland.

François Godard, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Camille Charles, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Alain Dautant, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Emilia Baranowska, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 01-224 Warsaw, Poland.

Natalia Skoczen, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France; Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 01-224 Warsaw, Poland.

Kewin Gombeau, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Marine Bouhier, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Hubert D Becker, UPR ‘Architecture et Réactivité de l’ARN’, CNRS, Institut de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Université de Strasbourg, F-67084 Strasbourg Cedex, France.

Sharon H Ackerman, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 48202, USA.

Lars M Steinmetz, European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), Genome Biology Unit, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany; Department of Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; Stanford Genome Technology Center, Palo Alto, CA 94304, USA.

Déborah Tribouillard-Tanvier, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Roza Kucharczyk, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 01-224 Warsaw, Poland.

Jean-Paul di Rago, CNRS, IBGC, University of Bordeaux, UMR 5095, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

Literature cited

- Ackerman SH. Atp11p and Atp12p are chaperones for F(1)-ATPase biogenesis in mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1555(1–3):101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman SH, Gatti DL, Gellefors P, Douglas MG, Tzagoloff A. ATP13, a nuclear gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae essential for the expression of subunit 9 of the mitochondrial ATPase. FEBS Lett. 1991;278(2):234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman SH, Tzagoloff A. ATP10, a yeast nuclear gene required for the assembly of the mitochondrial F1-F0 complex. J Biol Chem. 1990a;265(17):9952–9959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman SH, Tzagoloff A. Identification of two nuclear genes (ATP11, ATP12) required for assembly of the yeast F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990b;87(13):4986–4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman SH, Tzagoloff A. Function, structure, and biogenesis of mitochondrial ATP synthase. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;80:95–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiyar RS, Bohnert M, Duvezin-Caubet S, Voisset C, Gagneur J, Fritsch ES, Couplan E, von der Malsburg K, Funaya C, Soubigou F, et al. Mitochondrial protein sorting as a therapeutic target for ATP synthase disorders. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamura N, Capitanio N, Bonnefoy N, Papa S, Dujardin G. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae OXA1 gene is required for the correct assembly of cytochrome c oxidase and oligomycin-sensitive ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 1996;382(1–2):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arechaga I, Butler PJ, Walker JE. Self-assembly of ATP synthase subunit c rings. FEBS Lett. 2002;515(1–3):189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher EB, Groudinsky O, Dujardin G, Altamura N, Kermorgant M, Slonimski PP. Novel class of nuclear genes involved in both mRNA splicing and protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;215(3):517–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader G, Enkler L, Araiso Y, Hemmerle M, Binko K, Baranowska E, De Craene J-O, Ruer-Laventie J, Pieters J, Tribouillard-Tanvier D, et al. Assigning mitochondrial localization of dual localized proteins using a yeast Bi-Genomic Mitochondrial-Split-GFP. Elife. 2020;9:e56649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A, Korr D, Tzagoloff A. Shy1p is necessary for full expression of mitochondrial COX1 in the yeast model of Leigh’s syndrome. EMBO J. 2002;21(1–2):43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A, Zambrano A, Tzagoloff A. Mss51p and Cox14p jointly regulate mitochondrial Cox1p expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2004;23(17):3472–3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros MH, Tzagoloff A. Aep3p-dependent translation of yeast mitochondrial ATP8. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28(11):1426–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bietenhader M, Martos A, Tetaud E, Aiyar RS, Sellem CH, Kucharczyk R, Clauder-Münster S, Giraud M-F, Godard F, Salin B, et al. Experimental relocation of the mitochondrial ATP9 gene to the nucleus reveals forces underlying mitochondrial genome evolution. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(8):e1002876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy N, Fox TD. Genetic transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Methods Cell Biol. 2001;65:381–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14(2):115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Dieckmann CL. Cbp1p is required for message stability following 5'-processing of COB mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(24):16574–16578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson T, Rabinowitz M. Identification of multiple transcriptional initiation sites on the yeast mitochondrial genome by in vitro capping with guanylyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(22):14025–14033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déquard-Chablat M, Sellem CH, Golik P, Bidard F, Martos A, Bietenhader M, di Rago J-P, Sainsard-Chanet A, Hermann-Le Denmat S, Contamine V, et al. Two nuclear life cycle-regulated genes encode interchangeable subunits c of mitochondrial ATP synthase in Podospora anserina. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(7):2063–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann CL, Staples RR. Regulation of mitochondrial gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;152:145–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvezin-Caubet S, Caron M, Giraud MF, Velours J, di Rago JP. The two rotor components of yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase are mechanically coupled by subunit delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(23):13235–13240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner E, Schatz G. Mitochondrial assembly in respiration-deficient mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 3. A nuclear mutant lacking mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(15):5379–5384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis TP, Helfenbein KG, Tzagoloff A, Dieckmann CL. Aep3p stabilizes the mitochondrial bicistronic mRNA encoding subunits 6 and 8 of the H+-translocating ATP synthase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(16):15728–15733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan PM, Ellis TP, Nagley P, Lukins HB. The mature AEP2 gene product of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, required for the expression of subunit 9 of ATP synthase, is a 58 kDa mitochondrial protein. FEBS Lett. 1995;368(3):505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan PM, Payne MJ, Keramidaris E, Lukins HB. Characterization of a yeast nuclear gene, AEP2, required for accumulation of mitochondrial mRNA encoding subunit 9 of the ATP synthase. Curr Genet. 1991;20(1–2):53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanesi F. Mechanisms of mitochondrial translational regulation. IUBMB Life. 2013;65(5):397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foury F, Roganti T, Lecrenier N, Purnelle B. The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1998;440(3):325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TD. Translational control of endogenous and recoded nuclear genes in yeast mitochondria: regulation and membrane targeting. Experientia. 1996;52(12):1130–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TD. Mitochondrial protein synthesis, import, and assembly. Genetics. 2012;192(4):1203–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gari E, Piedrafita L, Aldea M, Herrero E. A set of vectors with a tetracycline-regulatable promoter system for modulated gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13(9):837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godard F, Tetaud E, Duvezin-Caubet S, di Rago JP. A genetic screen targeted on the FO component of mitochondrial ATP synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(20):18181–18189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruschke S, Kehrein K, Römpler K, Gröne K, Israel L, Imhof A, Herrmann JM, Ott M. Cbp3-Cbp6 interacts with the yeast mitochondrial ribosomal tunnel exit and promotes cytochrome b synthesis and assembly. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(6):1101–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruschke S, Ott M. The polypeptide tunnel exit of the mitochondrial ribosome is tailored to meet the specific requirements of the organelle. Bioessays. 2010;32(12):1050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruschke S, Römpler K, Hildenbeutel M, Kehrein K, Kühl I, Bonnefoy N, Ott M. The Cbp3-Cbp6 complex coordinates cytochrome b synthesis with bc(1) complex assembly in yeast mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2012;199(1):137–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin B, Labbe P, Somlo M. Preparation of yeast mitochondria (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) with good P/O and respiratory control ratios. Methods Enzymol. 1979;55:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell K, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Oxa1p acts as a general membrane insertion machinery for proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20(6):1281–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann JM, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Insertion into the mitochondrial inner membrane of a polytopic protein, the nuclear-encoded Oxa1p. EMBO J. 1997;16(9):2217–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann JM, Woellhaf MW, Bonnefoy N. Control of protein synthesis in yeast mitochondria: the concept of translational activators. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(2):286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildenbeutel M, Hegg EL, Stephan K, Gruschke S, Meunier B, Ott M. Assembly factors monitor sequential hemylation of cytochrome b to regulate mitochondrial translation. J Cell Biol. 2014;205(4):511–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JE, Myers AM, Koerner TJ, Tzagoloff A. Yeast/E. coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast. 1986;2(3):163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Dienhart MK, Stuart RA. Oxa1 directly interacts with Atp9 and mediates its assembly into the mitochondrial F1Fo-ATP synthase complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(5):1897–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabala AM, Lasserre JP, Ackerman SH, di Rago JP, Kucharczyk R. Defining the impact on yeast ATP synthase of two pathogenic human mitochondrial DNA mutations, T9185C and T9191C. Biochimie. 2014;100:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrein K, Moller-Hergt BV, Ott M. The MIOREX complex–lean management of mitochondrial gene expression. Oncotarget. 2015a;6(19):16806–16807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrein K, Schilling R, Moller-Hergt BV, Wurm CA, Jakobs S, Lamkemeyer T, Langer T, Ott M. Organization of mitochondrial gene expression in two distinct ribosome-containing assemblies. Cell Rep. 2015b;10:843–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk R, Dautant A, Gombeau K, Godard F, Tribouillard-Tanvier D, di Rago J-P. The pathogenic MT-ATP6 m.8851T>C mutation prevents proton movements within the n-side hydrophilic cleft of the membrane domain of ATP synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2019;1860(7):562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk R, Ezkurdia N, Couplan E, Procaccio V, Ackerman SH, Blondel M, di Rago J-P. Consequences of the pathogenic T9176C mutation of human mitochondrial DNA on yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6–7):1105–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk R, Giraud M-F, Brèthes D, Wysocka-Kapcinska M, Ezkurdia N, Salin B, Velours J, Camougrand N, Haraux F, di Rago J-P, et al. Defining the pathogenesis of human mtDNA mutations using a yeast model: the case of T8851C. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(1):130–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk R, Rak M, di Rago JP. Biochemical consequences in yeast of the human mitochondrial DNA 8993T>C mutation in the ATPase6 gene found in NARP/MILS patients. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793(5):817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk R, Salin B, di Rago JP. Introducing the human Leigh syndrome mutation T9176G into Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial DNA leads to severe defects in the incorporation of Atp6p into the ATP synthase and in the mitochondrial morphology. Hum Mol Genet. 2009b;18(15):2889–2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk R, Zick M, Bietenhader M, Rak M, Couplan E, Blondel M, Caubet S-D, di Rago J-P. Mitochondrial ATP synthase disorders: molecular mechanisms and the quest for curative therapeutic approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1793:186–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre-Legendre L, Balguerie A, Duvezin-Caubet S, Giraud M-F, Slonimski PP, Di Rago J-P. F1-catalysed ATP hydrolysis is required for mitochondrial biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae growing under conditions where it cannot respire. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47(5):1329–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre-Legendre L, Salin B, Schaëffer J, Brèthes D, Dautant A, Ackerman SH, di Rago J-P. Failure to assemble the alpha 3 beta 3 subcomplex of the ATP synthase leads to accumulation of the alpha and beta subunits within inclusion bodies and the loss of mitochondrial cristae in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(18):18386–18392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre-Legendre L, Vaillier J, Benabdelhak H, Velours J, Slonimski PP, di Rago JP. Identification of a nuclear gene (FMC1) required for the assembly/stability of yeast mitochondrial F(1)-ATPase in heat stress conditions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(9):6789–6796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytovchenko O, Naumenko N, Oeljeklaus S, Schmidt B, von der Malsburg K, Deckers M, Warscheid B, van der Laan M, Rehling P. The INA complex facilitates assembly of the peripheral stalk of the mitochondrial F1Fo-ATP synthase. EMBO J. 2014;33(15):1624–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick DU, Vukotic M, Piechura H, Meyer HE, Warscheid B, Deckers M, Rehling P. Coa3 and Cox14 are essential for negative feedback regulation of COX1 translation in mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(1):141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman C, Wilmes C, Tatsuta T, Langer T. Prohibitins interact genetically with Atp23, a novel processing peptidase and chaperone for the F1Fo-ATP synthase. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(2):627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M, Amunts A, Brown A. Organization and regulation of mitochondrial protein synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85:77–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M, Herrmann JM. Co-translational membrane insertion of mitochondrially encoded proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803(6):767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul MF, Barrientos A, Tzagoloff A. A single amino acid change in subunit 6 of the yeast mitochondrial ATPase suppresses a null mutation in ATP10. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(38):29238–29243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne MJ, Finnegan PM, Smooker PM, Lukins HB. Characterization of a second nuclear gene, AEP1, required for expression of the mitochondrial OLI1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1993;24(1–2):126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]