Abstract

Muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is an advanced stage of bladder cancer which poses a severe threat to life. Cancer development is usually accompanied by remarkable alterations in cell metabolism, and hence deep insights into MIBC at the metabolomic level can facilitate the understanding of the biochemical mechanisms involved in the cancer development and progression. In this proof-of-concept study, the optimal cutting temperature (OCT)-embedded MIBC samples were first washed with pure water to remove the polymer compounds which could cause severe signal suppression during mass spectrometry. Further, the tissue sections were analyzed by infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging (IR-MALDESI MSI), providing an overview on the spatially resolved metabolomic profiles, which enabled the discrimination between not only the cancerous and normal tissues, but also the subregions within a tissue section associated with different disease states. Using t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), the hyperdimensional MSI data was mapped into a two-dimensional space to visualize the spectral similarity, providing evidence that metabolomic alterations might have occurred outside the histopathological tumor border. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) was further employed to classify sample pathology in a pixel-wise manner, yielding excellent prediction sensitivity and specificity up to 96% based on the statistically characteristic spectral features. The results demonstrate great promise of IR-MALDESI MSI to identify molecular changes derived from cancer and unveil tumor heterogeneity, which can potentially promote the discovery of clinically relevant biomarkers and allow for applications in precision medicine.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, IR-MALDESI mass spectrometry imaging, metabolomics, lipidomics, intratumor heterogeneity

Introduction

Bladder cancer ranks the 4th most common cancer among men in the United States (www.urologyhealth.org). Approximately 25% of bladder cancer cases are muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) with an overall 5-year survival rate of 40–60% after being treated by radical cystectomy (Ogawa et al. 2020) and/or chemo-radiation in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting (Ma and Black 2021). Many studies have shown that metabolomes and lipidomes undergo significant changes during cancer development to allow rapidly growing cancer cells to maintain viability (Lin et al. 2017). A thorough understanding of cancer metabolism can offer invaluable insights into key biological events involved in cancer initiation and progression, and aid in identifying diagnostic biomarkers (Morse et al. 2019). Due to the enormous diversity in metabolite structures and characteristics, the metabolomic and lipidomic analysis of cancer primarily relies on chromatography-mass spectrometry (Cui et al. 2018; Struck-Lewicka et al. 2015; Urayama et al. 2010) due to its high molecular specificity and coverage, in which case generally a big piece of specimen is homogenized and undergoes extensive sample preparation where tumor heterogeneity is neglected. Herein, an imaging approach retaining spatial information so allowing assessments of microenvironments is desirable. Imaging of proteins in biological tissues is well established using labeling techniques, e.g, immunohistochemistry to map target antigens, while spatial detection of small metabolites is still under development. Over the last decade, innovative imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been exploited in clinical laboratories as the non-invasive nature enables their use in monitoring cancer metabolism in vivo (Lin et al. 2017). However, these modalities are subject to several inherent limitations such as narrow chemical information, poor sensitivity and specificity, and requirement of labeling.

Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) is an objective imaging method of which feasibility of assessing microenvironments within tissue sections has been proven on a broad variety of diseases lately (Banerjee et al. 2017; Calligaris et al. 2014; Dória et al. 2016a; Jarmusch et al. 2016). The label-free nature and qualitative/ quantitative capability of MSI allow for the investigation of spatial distributions of numerous biomolecules simultaneously, which is well suited for untargeted discovery studies. Ion images are constructed by incorporating the spatial locations and ion abundances, which can be associated with the corresponding histological images to study the biomolecular signatures from specific subregions at distinct disease states. A substantial amount of recent cancer studies with desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) have demonstrated the value of ambient MSI in depth molecular profiling, and accurate cancer diagnosis with minimal sample preparation and analysis in near-physiological conditions (Cordeiro et al. 2020; Eberlin et al. 2014; Margulis et al. 2018; Pirro et al. 2017). Another emerging ambient MSI technique is infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (IR-MALDESI) which uses a mid IR-laser to resonantly excite water for direct tissue characterization. The complete ablation of a tissue slice over the irradiated area owing to the micrometer-scale penetration depth of an IR laser enables reproducible volumes to be sampled. The ionization mechanism of IR-MALDESI is demonstrated to be the post-electrospray ionization of ablated neutral materials (Dixon and Muddiman 2010; Rosen et al. 2015; Sampson et al. 2008; Tu and Muddiman 2019a). Over the past decade, IR-MALDESI MSI has established its utility for studying the lipid and metabolite distributions in various subjects including but not limited to cancerous ovaries (Nazari and Muddiman 2016), single mammalian cells (Xi et al. 2020) and fresh bones (Khodjaniyazova et al. 2019), with high repeatability (Tu and Muddiman 2019b) and good lipidome and metabolome coverage (Pace et al. 2020), indicating its high potential in cancer research.

One challenge in analyzing clinically relevant tissue is that the frozen tissue sample is oftentimes preserved in an embedding medium to assist cryosectioning and maintain its morphological characteristics. The most common medium used nowadays is optimal cutting temperature (OCT) which consists of polyethylene glycol, polyvinyl alcohol and nonreactive ingredients (Snijders et al. 2019; Vrana et al. 2016). Nonetheless, the polymers from OCT raise difficulties in MS analysis as they severely suppress informative biological signals by competing for the available ions. In this proof-of-concept study, we demonstrated a simple and effective washing step to remove OCT from tissue samples without impacts on the tissue morphology. The washed samples were then subject to positive and negative IR-MALDESI MSI for characterization of the metabolomic and lipidomic profiles of MIBC. Multivariate statistical analyses were further conducted in an attempt to unravel biomolecules associated with disease states and perform cancer diagnosis relying on the m/z patterns.

Experimental

Human Bladder Tissue Collection

Deidentified human bladder tissues including 6 tumor samples with their 6 adjacent matching normal tissues were collected at Tumor Tissue and Pathology Shared Resources (TTPSR) at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (WFBMC) and Comprehensive Cancer Center under approved IRB (IRB00036014). The tissue samples were snap-frozen, embedded in OCT blocks and then stored at −80 °C until analysis. The demographic and clinical information of all tissue samples is detailed in supplementary Table S1.

Histology

All tumor specimens were high grade MIBC that showed significant loss of urothelial morphology and deep infiltration and invasion of detrusor muscle. Tumors were of stage pT2b, pT3 and pT4 according to The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Urinary System (Humphrey et al. 2016) (Table S1). Adjacent histologically non-malignant “normal” tissues mainly comprised stroma and smooth muscles.

Sample Preparation

Human bladder tissues embedded in OCT media were cryosectioned into 20-μm sections using a cryomicrotome (CM 1950, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) at −20 °C, and thaw-mounted onto microscope slides. To remove OCT, each sample slide was submerged into pure water for 60 s, followed by into fresh water for another 30 s with gentle and careful stir during the washing steps. Sample slides were allowed to air dry for approximately 10 min prior to imaging.

IR-MALDESI MSI

IR-MALDESI employs a “burst-mode” 2970-nm laser with a pulse rate up to 10 kHz (JGM Associates, Inc., Burlington, MA) to induce sample ablation. 6 pulses/burst with a total energy of approximately 1.1 mJ was applied in each laser shot. An ice layer was uniformly deposited on the sample surface as a mid-IR absorbing matrix by cooling the sample stage down to −8 °C and keeping the relative humidity in the sample enclosure at approximately 12% (Robichaud et al. 2014). The electrospray solvent of 50:50:0.2 v/v/v acetonitrile/water/formic acid (Bagley et al. 2020) was infused at a flow rate of 1.5 μLmin−1 for post-electrospray ionization of ablated neutral species. All solvents were in Optima grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA).

The IR-MALDESI source is coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris™ 240 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The mass spectrometer was operated in “Small Molecules” mode with a RF lens of 70%. The spray voltage was set to be 3.5 kV and 3.2 kV for positive and negative mode, respectively. The capillary temperature was 350 °C. Mass spectra of all samples were acquired over m/z range 160–1000, with a resolving power of 240,000fwhm at m/z 200. Mass calibration was performed daily prior to analysis using the Pierce™ FlexMix™ Calibration Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the EASY-IC™ ion source was on for real-time mass calibration. The automatic gain control function (AGC) was disabled, and the injection time was held constantly as 15 ms to coordinate the laser desorption and ion acquisition events. For each tissue sample, half was subjected to positive IR-MALDESI MSI and the other half was to negative IR-MALDESI MSI. Tissue sections were imaged separately, generating a total of 12 positive and 12 negative MSI data sets. Pixel size was 100 μm-by-100 μm.

Data Processing and Visualization

The initial data files were stored in Xcalibur raw file format and converted into mzML files using MSConvert from the ProteoWizard toolkit, and then converted into imzML image files by imzMLConverter. imzML files were loaded into MSiReader v1.02 (https://msireader.wordpress.ncsu.edu/) for visualization, preprocessing and analysis (Bokhart et al. 2018; Robichaud et al. 2013). Ion images were presented with ± 2.5 ppm mass tolerance. The MSiPeakfinder was used to select species that displayed more than 2-fold abundances in either tumors or normal tissues in comparison with the background area and were above an abundance threshold of 100. Consecutively, 1338 and 685 ions in positive and negative mode were selected as tissue-specific, respectively. The MSiReader built-in MSiExport tool was used to export ion abundance values from each pixel for further statistical analyses.

Metabolites and lipids were putatively annotated via METASPACE (Palmer et al. 2017) using the HMDB-v4 and LipidMaps-2017–12-12 with a false discovery rate of 10%. Only ions marked as “on sample” were reported. The imaging files are public at https://metaspace2020.eu/project/tu-2021, and the annotation results are available in Supplemental File 1. METLIN (Guijas et al. 2018) was alternatively used to annotate monoisotopic masses (< ±2.5 ppm mass error) that were not annotated by METASPACE, such as ions detected as [M+H+-H2O]+.

Multivariate Statistical Analyses

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) is an unsupervised and non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithm that has been introduced to the MSI field recently (Abdelmoula et al. 2016; Fonville et al. 2013). In this study it was utilized to visualize the high-dimensional MSI data in a two-dimensional space to expose the similarity relationships of data points from different disease states. Tissue-specific ion abundances were exported from subregions corresponding to varying pathologies, i.e., 100 pixels on each sample (either tumor or normal), and 100 pixels on the adjacent smooth muscle regions in tumor #1999–129 and #2002–322. The subregions were reviewed and annotated through histopathological evaluation of the H&E stained slides, which are shown in Fig. S1 and Fig. S2 together with the pixels of interest used for statistical analysis. Data was first normalized to the total ion current (TIC) and log-transformed, and was processed by t-SNE with the MatLab function tsne using the default settings.

To demonstrate the feasibility of IR-MALDESI MSI to identify characteristic biomarkers and differentiate sample types, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) as an embedded method which simultaneously processes feature selection with a machine learning classifier was used in this study. LASSO is a linear regression model with the goal of minimizing the residual sum of squares of the model subject to the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients which has to be less than a fixed value (Muthukrishnan and Rohini 2016). To do so, it shrinks the coefficients of the less associated variables to 0 to remove the redundant variables and thus select the most discriminative ones for the subsequent prediction purpose. The LASSO model was trained on the mass spectral data from all samples except #2002–342 using the “glmnet” package v4.1 in the R language. A total of 1000 pixels from the five patients were merged in the training set, where 100 pixels were from each sample (either tumor or normal tissue). The regularization parameter λ was determined by 10-fold cross-validation on the training set, and the one at the minimum misclassification error was chosen for the LASSO model. The model was subsequently tested on an independent sample pair from Patient #2002–342 to predict the sample type (i.e., tumor or normal) in a pixel-wise manner, and the classification sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) were calculated to evaluate the predictive performance.

Results and Discussion

Molecular Profiling of Human Bladder Tissues

Removal of the OCT embedding media was necessary prior to the MS analysis to avoid signal suppression. Fig. S3 shows that after approximately 90 s of dipping the sample slide into pure water with gentle agitation, the OCT layer was removed and the polymer peaks were vastly reduced (e.g., average ion flux at m/z 476.6260 was 2.4×105 versus 800 before/ after washing), while holding the slide stationary resulted in predominant OCT background which was indicative of incomplete removal of the OCT compounds.

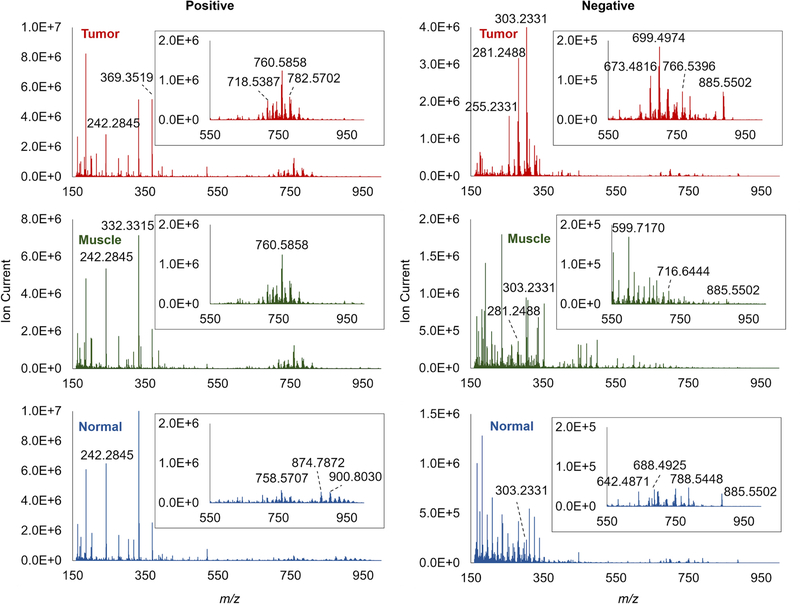

After tissue washing, 6 matching pairs of bladder tissues were investigated by positive and negative IR-MALDESI MSI. Overall, dramatic spectral differences can be observed between tumor and normal tissues, while the adjacent smooth muscle regions in tumor show a certain extent of similarity to both tumor and normal (Fig. 1). The tumor samples appear to exhibit higher ion abundances in the mass range of m/z 650–850 in positive mode and m/z 250–350 in negative mode, which are typically associated with phospholipids (PLs) and long-chain fatty acids (FAs), respectively. The normal samples were found to contain more larger lipids in the mass range of m/z 850–1000 in positive mode, e.g., triglyceride TG (54:4) with NH4+ adduct at m/z 900.8030.

Fig. 1.

Representative mass spectra recorded from bladder tumor (top), adjacent smooth muscle regions within tumor (middle) and normal tissue (bottom). Inserts: zoom-in spectra at m/z 550–1000.

In regard to the coverage of biomolecules, more species were putatively identified in the tumor samples compared to their normal counterparts. For instance, in positive mode 622 and 388 unique annotations were assigned to the tumor and to the control via METASPACE LipidMaps database, respectively, and in negative mode it was 435 versus 162 unique annotations (Supplementary Material 1). The vast majority of detected species in positive mode were classified as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), ceramide (Cer), sphingomyelin (SM), glycerides, steroid and cholesteryl ester (CE). In negative mode the detected classes are mainly FA, hydroxy FA, FA ester, phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylserine (PS) and ceramide phosphate. Certain molecules detected in positive mode were also present in negative mass spectral, such as monoglyceride (MG), diglyceride (DG) and PE as deprotonated species.

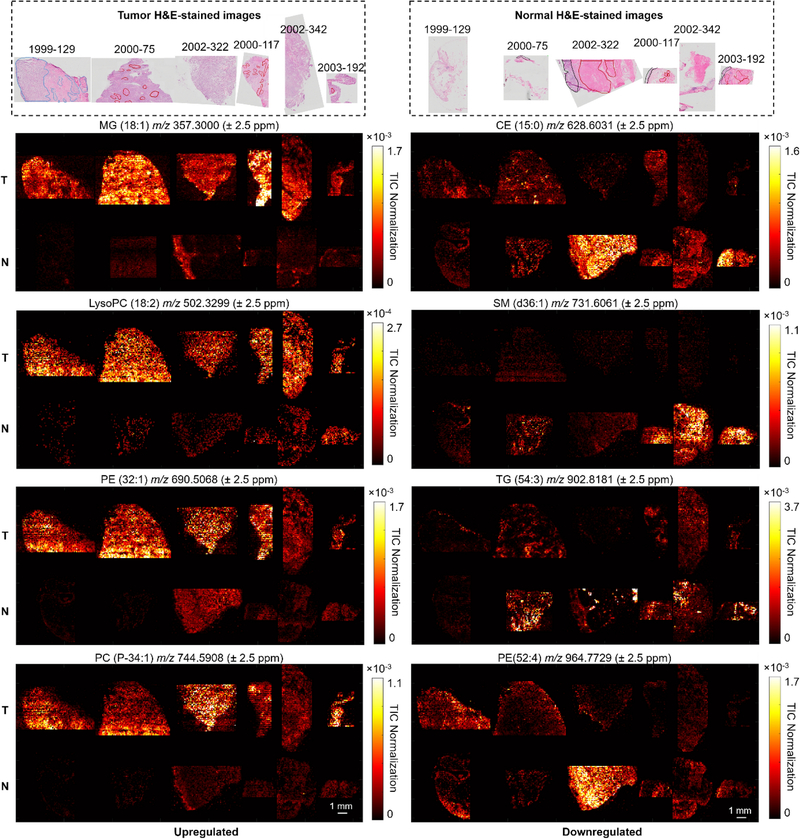

Visualization of Molecular Alterations between Tumor and Normal Bladder

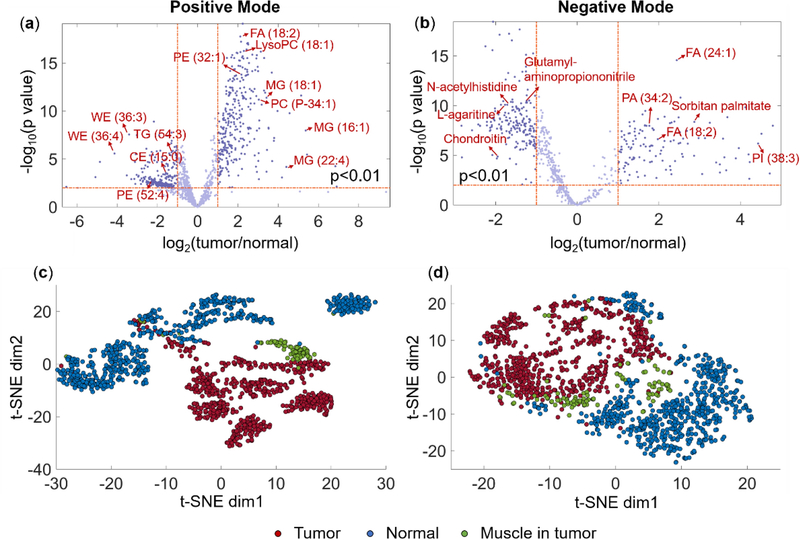

Two-sample t-test was carried out on all tissue-specific ions (1338 in positive mode and 685 in negative mode; please find the peak selection criteria in Data Processing and Visualization) to determine the statistical significances (i.e., p-values) of their abundances in tumors relative to normal tissues. Then the p-values were presented against the log2 fold changes in ion abundances via the volcano plot (Fig. 2a and 2b) to identify significant changes, where the upregulated species in tumor versus normal bladder tissues were located on the right and the downregulated species were on the left. The ions with p-values ≤0.01 and fold changes ≥2 were considered significantly altered in bladder cancer and putatively annotated through database searching, which are listed in Supplementary Material 2. The results revealed distinct lipid and metabolite constituents between tumor and normal tissues. In positive mode, PLs including lysoPC, PC, lysoPE and PE species were amongst the most abundant in tumors (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4), which corroborates the observations with the mass spectra. The overexpression of PC and PE composition has been frequently reported in diverse cancer types (Mirnezami et al. 2014; Ouyang et al. 2017; Porcari et al. 2018). PC and PE are the first two most common constituents of the lipid bilayer (Szlasa et al. 2020), participating in various cellular processes such as cell division and proliferation (Mao et al. 2016), bioactive molecules production (e.g., DG (Momchilova and Markovska 1999)), and membrane protein folding (Bogdanov and Dowhan 1998). Glycerides including MGs and DGs are also present at higher abundances in tumor.

Fig. 2.

Volcano plots of tissue-specific ions (−log10 of the t-test p-value versus log2 of the fold change tumor/normal) in (a) positive and (b) negative mode. Each data point in the volcano plots represents a tissue-specific ion of which selection criteria are detailed in Data Processing and Visualization. Representative statistically changed metabolites are labeled in the volcano plots. t-SNE scatter plots visualize the MSI data points from tumor (n=600, red filled circles), adjacent muscle in tumor (n=100, green filled circles) and normal tissue (n=600, blue filled circles) in (c) positive and (d) negative mode in two dimensions.

Fig. 3.

Selected ion images from the tumor (T) and normal (N) samples acquired by positive mode IR-MALDESI MSI: left, upregulated species; right, downregulated species. Putative annotations were obtained via METASPACE database search. The corresponding H&E-stained images of adjacent tissue sections are shown on top, where the smooth muscle regions were outlined with red lines, except for tumor #1999–129 where the tumor regions were outlined with blue lines and the rest area was smooth muscle. The scale bar represents 1 mm.

Nonetheless, not all PLs are elevated in tumor. For instance, the normal tissues are rich in very-long-chain PEs such as PE (52:4) (Fig. 3). In addition, some wax ester (WE), sphingomyelin (SM) and cholesteryl ester (CE) species display higher ion abundances in the normal tissues, such as SM (d36:1), SM (d42:3) and CE (15:0) (Fig. 3 and Fig. S5). The ion images also clearly reflected the intratumor heterogeneity. For instance, MG (18:1) showed a specific localization in the tumor regions but was weak or absent in the neighboring benign smooth muscle regions in the tumor samples, while an increased abundance of CE (15:0) behaves in the opposite manner.

In negative mode, one class of molecules observed with prominent and consistent increase in tumor was free fatty acids (FAs) (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6). This result is in accordance with the published studies on other cancer types (Mao et al. 2016; Margulis et al. 2018). FAs are the essential building blocks for a large variety of lipid species (Koundouros and Poulogiannis 2020). Elevated biosynthesis of de novo FAs in cancer cells not only maintains the rapid cellular proliferation (Baenke et al. 2013), but also serves as an essential energy source (Röhrig and Schulze 2016). Some complex lipid species such as PI and PA, were also found concentrated in the bladder tumors (Fig. S7). The level of PI expression has been reported to markedly increase in prostate cancer (Goto et al. 2014). This could be related to the elevated cellular signaling activity (Krauß and Haucke 2007). PA class was also found richer in ovarian cancer versus control (Dória et al. 2016b). The normal bladder tissues show an enhancement in some glutamine derivatives, such as γ-glutamyl-β-aminopropiononitrile at m/z 198.0884 (Fig. 4). This could potentially be linked to an elevated γ-glutamyl transferase activity (a clinical indicator of tissue damage (Heisterkamp et al. 2008)) in tumor, and γ-glutamyl-β-aminopropiononitrile is one of its substrates. The tumor heterogeneity was also exhibited in negative mode, allowing clear visualization of the tumor regions and the neighboring benign smooth muscle regions within the tumor samples.

Fig. 4.

Selected ion images from the tumor (T) and normal (N) samples acquired by negative mode IR-MALDESI MSI: left, upregulated species; right, downregulated species. Putative annotations were obtained via METASPACE database search. The corresponding H&E-stained images of adjacent tissue sections are shown on top, where the smooth muscle regions were outlined with red lines, except for tumor #1999–129 where the tumor regions were outlined with blue lines and the rest area was smooth muscle. The scale bar represents 1 mm.

Data analysis and interpretation in MSI studies can be difficult due to the high dimensionality of the data. Manual inspection of individual ion images to distinguish tumor can be time- and labor-consuming and tend to neglect the correlations between ions. t-SNE as a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method was performed on the spectral data from pathology-defined subregions of the bladder tissues in order to visualize the results of the high-dimensional MSI datasets in a low-dimensional representation while retaining a lot of the original information. Compared with linear methods which mainly focus on the global data structure, nonlinear dimensionality reduction approaches can preserve both local similarities and global characteristics (Abdelmoula et al. 2016). The two-dimensional scatter plots are displayed in Fig. 2c and 2d, yielding apparent separation of tumor and normal data points, indicating that their molecular signatures are characteristically different. The moderate dispersed grouping could mainly be attributed to the patient-to-patient variability. It is interesting to note that the data points from the muscle cells in the vicinity of tumor fell between the tumor and the normal clusters, likely indicating the neighboring smooth muscle regions have mixed molecular profiles of both tumor and normal tissues. For instance, a tumor-upregulated ion at m/z 263.2369, putatively identified as octadecatrienal and isomers, in adjacent smooth muscles showed the same level as in normal (p=0.26), whereas PE (40:2) at m/z 800.6164 in adjacent smooth muscles expressed similar level as in tumor (p=0.22), which was 15× less in normal (p=5.81×10−23) (Fig. S8). Indeed, some other studies have also shown that the molecular tumor margin could exceed the histologically defined tumor margin (Banerjee et al. 2017; Oppenheimer et al. 2010), implying possible aberrant cell events occurring in the immediately adjacent normal cells. The hypotheses proposed by Oppenheimer et al (Oppenheimer et al. 2010) for this phenomenon were that the seemingly normal cells might be infiltrative tumor cells or precancerous cells; or it could be a result of the interactions between the tumor and adjacent cells. Our study provides additional evidence that the underlying molecular alterations might have already occurred in the normal-appearing regions beyond the histological tumor border, underlining the cellular complexity of tumor.

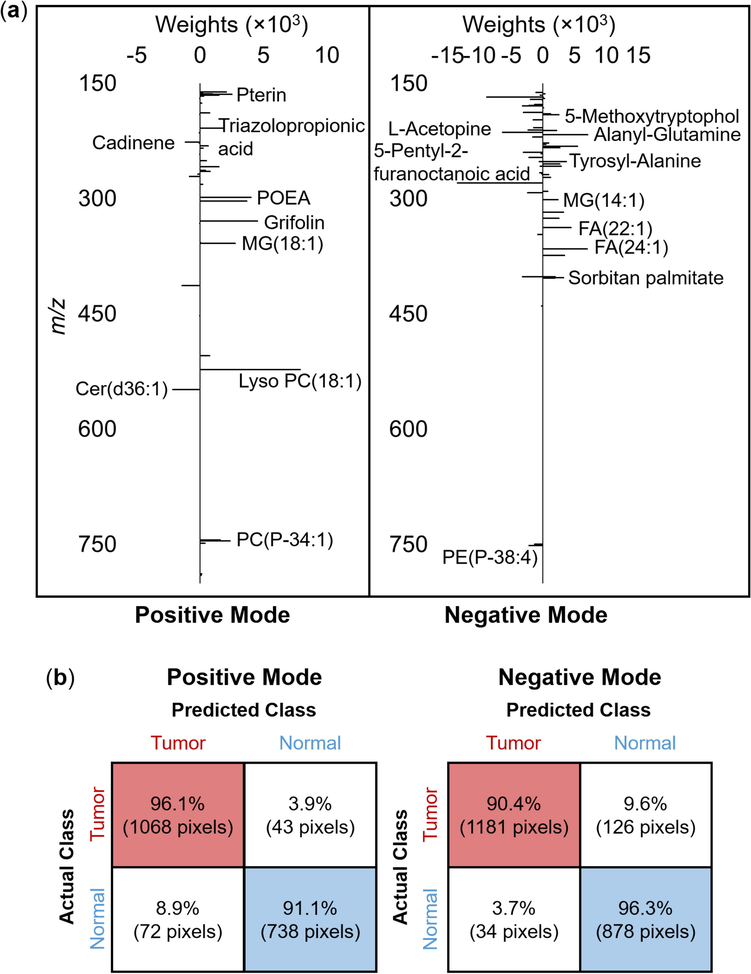

LASSO Prediction of Bladder Cancer and Corresponding Normal Tissue

A binary LASSO model was constructed to fulfill feature selection and disease classification using the training set including data points from five out of six patients. 10-fold cross-validation was employed for parameter tuning and the regularization parameter λ at the minimum misclassification error was chosen for the LASSO model. A total of 40 and 61 m/z features in positive and negative ionization mode, respectively, showing the best discriminative power were selected by LASSO and are displayed in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Material 3 with their putative identifications, where the features with positive weights represent that they are characteristic of tumor, while negative weights represent the opposite.

Fig. 5.

(a) Discriminating mass spectral features with their weights obtained by the LASSO model in positive and negative mode. Putative annotations were made via METASPACE, which were detailed in Supplementary Material 3. (b) LASSO per-pixel prediction results on Patient #2002–342.

To evaluate its performance for MIBC diagnosis based on the IR-MALDESI MSI data, the LASSO model was further applied to an independent dataset (i.e., patient #2002–342) to predict the sample class per pixel (Fig. 5b), yielding a sensitivity of 96.1% and a specificity of 91.1% in positive mode, and a sensitivity of 90.4% and a specificity of 96.3% in negative mode, indicating that the spectral features detected by IR-MALDESI are highly predictable.

Conclusions

This work demonstrates the feasibility of IR-MALDESI MSI in capturing informative molecular fingerprints that are indictive of disease states. In combination with a dimensionality reduction approach, cancerous and normal tissues were differentiated and potential molecular alterations beyond the histological tumor margin were revealed. LASSO as a feature selection technique and machine learning classifier allowed for identifying discriminative biomolecules and accurate prediction of disease states of new data. The results offer a proof of concept that IR-MALDESI MSI can be a complementary imaging approach to the existing imaging modalities for cancer research to provide in-depth molecular information and a comprehensive picture of cancer metabolism, which may provoke vital clinical implications. Note that the current work on the limited number of samples was exploratory and preliminary. In the future study the findings in this work will be validated in a larger patient cohort, and the significantly changed species will be unambiguously identified via tandem MS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-CA193437R01(to NS), the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center Tumor Tissue and Pathology Shared Resource (TTPSR), supported by the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Center Support Grant award number P30CA012197, and the NIH grant R01GM087964 (to DCM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute. The MSI analysis was performed in the Molecular Education, Technology and Research Innovation Center (METRIC) at NC State University.

Abbreviations

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- FA

fatty acid

- MG

monoglyceride

- DG

diglyceride

- TG

triglyceride

- CE

cholesteryl ester

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This AM is a PDF file of the manuscript accepted for publication after peer review, when applicable, but does not reflect post-acceptance improvements, or any corrections. Use of this AM is subject to the publisher’s embargo period and AM terms of use. Under no circumstances may this AM be shared or distributed under a Creative Commons or other form of open access license, nor may it be reformatted or enhanced, whether by the Author or third parties. See here for Springer Nature’s terms of use for AM versions of subscription articles: https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/policies/accepted-manuscript-terms

Data Availability

The data sets are available at https://metaspace2020.eu/project/tu-2021.

References

- Abdelmoula WM, Balluff B, Englert S, Dijkstra J, Reinders MJT, Walch A, et al. (2016). Data-driven identification of prognostic tumor subpopulations using spatially mapped t-SNE of Mass spectrometry imaging data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(43), 12244–12249. 10.1073/pnas.1510227113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenke F, Peck B, Miess H, & Schulze A (2013). Hooked on fat: The role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms, 6(6), 1353–1363. 10.1242/dmm.011338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley MC, Ekelöf M, & Muddiman DC (2020). Determination of optimal electrospray parameters for lipidomics in infrared-matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 31(2), 319–325. 10.1021/jasms.9b00063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Zare RN, Tibshirani RJ, Kunder CA, Nolley R, Fan R, et al. (2017). Diagnosis of prostate cancer by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometric imaging of small metabolites and lipids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(13), 3334–3339. 10.1073/pnas.1700677114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov M, & Dowhan W (1998). Phospholipid-assisted protein folding: Phosphatidylethanolamine is required at a late step of the conformational maturation of the polytopic membrane protein lactose permease. EMBO Journal, 17(18), 5255–5264. 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokhart MT, Nazari M, Garrard KP, & Muddiman DC (2018). MSiReader v1.0: Evolving open-source mass spectrometry imaging software for targeted and untargeted analyses. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 29(1), 8–16. 10.1007/s13361-017-1809-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calligaris D, Caragacianu D, Liu X, Norton I, Thompson CJ, Richardson AL, et al. (2014). Application of desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging in breast cancer margin analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(42), 15184–15189. 10.1073/pnas.1408129111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro FB, Jarmusch AK, León M, Ferreira CR, Pirro V, Eberlin LS, et al. (2020). Mammalian ovarian lipid distributions by desorption electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (DESI-MS) imaging. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 412, 1251–1262. 10.1007/s00216-019-02352-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Lu H, & Lee YH (2018). Challenges and emergent solutions for LC-MS/MS based untargeted metabolomics in diseases. Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 37(6), 772–792. 10.1002/mas.21562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RB, & Muddiman DC (2010). Study of the ionization mechanism in hybrid laser based desorption techniques. Analyst, 135(5), 880–882. 10.1039/b926422a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dória ML, McKenzie JS, Mroz A, Phelps DL, Speller A, Rosini F, et al. (2016a). Epithelial ovarian carcinoma diagnosis by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–11. 10.1038/srep39219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dória ML, McKenzie JS, Mroz A, Phelps DL, Speller A, Rosini F, et al. (2016b). Epithelial ovarian carcinoma diagnosis by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–11. 10.1038/srep39219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberlin LS, Tibshirani RJ, Zhang J, Longacre TA, Berry GJ, Bingham DB, et al. (2014). Molecular assessment of surgical-resection margins of gastric cancer by mass-spectrometric imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(7), 2436–2441. 10.1073/pnas.1400274111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonville JM, Carter CL, Pizarro L, Steven RT, Palmer AD, Griffiths RL, et al. (2013). Hyperspectral visualization of mass spectrometry imaging data. Analytical Chemistry, 85(3), 1415–1423. 10.1021/ac302330a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T, Terada N, Inoue T, Nakayama K, Okada Y, Yoshikawa T, et al. (2014). The expression profile of phosphatidylinositol in high spatial resolution imaging mass spectrometry as a potential biomarker for prostate cancer. PLoS ONE, 9(2), e90242. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guijas C, Montenegro-Burke JR, Domingo-Almenara X, Palermo A, Warth B, Hermann G, et al. (2018). METLIN: A technology platform for identifying knowns and unknowns. Analytical Chemistry, 90(5), 3156–3164. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisterkamp N, Groffen J, Warburton D, & Sneddon TP (2008). The human gamma-glutamyltransferase gene family. Human Genetics, 123(4), 321–332. 10.1007/s00439-008-0487-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, & Reuter VE (2016). The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs—Part B: prostate and bladder tumours. European Urology, 70(1), 106–119. 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmusch AK, Pirro V, Baird Z, Hattab EM, Cohen-Gadol AA, & Cooks RG (2016). Lipid and metabolite profiles of human brain tumors by desorption electrospray ionization-MS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(6), 1486–1491. 10.1073/pnas.1523306113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjaniyazova S, Hanne NJ, Cole JH, & Muddiman DC (2019). Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) of fresh bones using infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (IR-MALDESI). Analytical Methods, 11(46), 5929–5938. 10.1039/c9ay01886g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koundouros N, & Poulogiannis G (2020). Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 122(1), 4–22. 10.1038/s41416-019-0650-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauß M, & Haucke V (2007). Phosphoinositide-metabolizing enzymes at the interface between membrane traffic and cell signalling. EMBO Reports, 8(3), 241–246. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Keshari KR, & Park JM (2017). Cancer metabolism and tumor heterogeneity: Imaging perspectives using MR imaging and spectroscopy. Contrast Media and Molecular Imaging, 2017. 10.1155/2017/6053879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, & Black PC (2021). Current perioperative therapy for muscle invasive bladder cancer. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, 35(3), 495–511. 10.1016/j.hoc.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, He J, Li T, Lu Z, Sun J, Meng Y, et al. (2016). Application of imaging mass spectrometry for the molecular diagnosis of human breast tumors. Scientific Reports, 6(October 2015), 1–12. 10.1038/srep21043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulis K, Chiou AS, Aasi SZ, Tibshirani RJ, Tang JY, & Zare RN (2018). Distinguishing malignant from benign microscopic skin lesions using desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(25), 6347–6352. 10.1073/pnas.1803733115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnezami R, Spagou K, Vorkas PA, Lewis MR, Kinross J, Want E, et al. (2014). Chemical mapping of the colorectal cancer microenvironment via MALDI imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-MSI) reveals novel cancer-associated field effects. Molecular Oncology, 8(1), 39–49. 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momchilova A, & Markovska T (1999). Phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine are sources of diacylglycerol in ras-transformed NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, 31(2), 311–318. 10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse N, Jamaspishvili T, Simon D, Patel PG, Ren KYM, Wang J, et al. (2019). Reliable identification of prostate cancer using mass spectrometry metabolomic imaging in needle core biopsies. Laboratory Investigation, 99(10), 1561–1571. 10.1038/s41374-019-0265-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukrishnan R, & Rohini R (2016). LASSO: A feature selection technique in predictive modeling for machine learning. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Advances in Computer Applications (ICACA), 18–20. 10.1109/ICACA.2016.7887916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari M, & Muddiman DC (2016). Polarity switching mass spectrometry imaging of healthy and cancerous hen ovarian tissue sections by infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (IR-MALDESI). Analyst, 141(2), 595–605. 10.1039/c5an01513h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Shimizu Y, Uketa S, Utsunomiya N, & Kanamaru S (2020). Prognosis of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer who are intolerable to receive any anti-cancer treatment. Cancer Treatment and Research Communications, 24, 100195. 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SR, Mi D, Sanders ME, & Caprioli RM (2010). A molecular analysis of tumor margins by MALDI mass spectrometry in renal carcinoma. Journal of Proteome Research, 9(5), 2182–2190. 10.1021/pr900936z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y, Liu J, Nie B, Dong N, Chen X, Chen L, & Wei Y (2017). Differential diagnosis of human lung tumors using surface desorption atmospheric pressure chemical ionization imaging mass spectrometry. RSC Advances, 7(88), 56044–56053. 10.1039/c7ra11839b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pace CL, Horman B, Patisaul H, & Muddiman DC (2020). Analysis of neurotransmitters in rat placenta exposed to flame retardants using IR-MALDESI mass spectrometry imaging. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 412(15), 3745–3752. 10.1007/s00216-020-02626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A, Phapale P, Chernyavsky I, Lavigne R, Fay D, Tarasov A, et al. (2017). FDR-controlled metabolite annotation for high-resolution imaging mass spectrometry. Nature Methods, 14(1), 57–60. 10.1038/nmeth.4072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirro V, Alfaro CM, Jarmusch AK, Hattab EM, Cohen-Gadol AA, & Cooks RG(2017). Intraoperative assessment of tumor margins during glioma resection by desorption electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(26), 6700–6705. 10.1073/pnas.1706459114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcari AM, Zhang J, Garza KY, Rodrigues-Peres RM, Lin JQ, Young JH, et al. (2018). Multicenter study using desorption-electrospray-ionization-mass-spectrometry imaging for breast-cancer diagnosis. Analytical Chemistry, 90(19), 11324–11332. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b01961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud G, Barry JA, & Muddiman DC (2014). IR-MALDESI mass spectrometry imaging of biological tissue sections using ice as a matrix. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 25(3), 319–328. 10.1007/s13361-013-0787-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud G, Garrard KP, Barry JA, & Muddiman DC (2013). MSiReader: An open-source interface to view and analyze high resolving power MS imaging files on matlab platform. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 24(5), 718–721. 10.1007/s13361-013-0607-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röhrig F, & Schulze A (2016). The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 16(11), 732–749. 10.1038/nrc.2016.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen EP, Bokhart MT, Ghashghaei HT, & Muddiman DC (2015). Influence of desorption conditions on analyte sensitivity and internal energy in discrete tissue or whole body imaging by IR-MALDESI. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 26(6), 899–910. 10.1007/s13361-015-1114-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson JS, Hawkridge AM, & Muddiman DC (2008). Development and characterization of an ionization technique for analysis of biological macromolecules: liquid matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization. Analytical Chemistry, 80(17), 6773–6778. 10.1021/ac8001935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders MLH, Zajec M, Walter LAJ, de Louw RMAA, Oomen MHA, Arshad S, et al. (2019). Cryo-Gel embedding compound for renal biopsy biobanking. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–10. 10.1038/s41598-019-51962-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struck-Lewicka W, Kordalewska M, Bujak R, Yumba Mpanga A, Markuszewski M, Jacyna J, et al. (2015). Urine metabolic fingerprinting using LC-MS and GC-MS reveals metabolite changes in prostate cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 111, 351–361. 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szlasa W, Zendran I, Zalesińska A, Tarek M, & Kulbacka J (2020). Lipid composition of the cancer cell membrane. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes, 52(5), 321–342. 10.1007/s10863-020-09846-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu A, & Muddiman DC (2019a). Internal energy deposition in infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization with and without the use of ice as a matrix. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 30(11), 2380–2391. 10.1007/s13361-019-02323-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu A, & Muddiman DC (2019b). Systematic evaluation of repeatability of IR-MALDESI-MS and normalization strategies for correcting the analytical variation and improving image quality. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 411(22), 5729–5743. 10.1007/s00216-019-01953-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urayama S, Zou W, Brooks K, & Tolstikov V (2010). Comprehensive mass spectrometry based metabolic profiling of blood plasma reveals potent discriminatory classifiers of pancreatic cancer. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 24, 613–620. 10.1002/rcm.4420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana M, Goodling A, Afkarian M, & Prasad B (2016). An optimized method for protein extraction from OCT-embedded human kidney tissue for protein quantification by LC-MS/MS proteomics. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 44(10), 1692–1696. 10.1124/dmd.116.071522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y, Tu A, & Muddiman DC (2020). Lipidomic profiling of single mammalian cells by infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (IR-MALDESI). Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 412(29), 8211–8222. 10.1007/s00216-020-02961-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets are available at https://metaspace2020.eu/project/tu-2021.