Abstract

Diarylamines are obtained directly from sulfinamides through a novel rearrangement sequence. The transformation is transition metal-free and proceeds under mild conditions, providing facile access to highly sterically hindered diarylamines that are otherwise inaccessible by traditional SNAr chemistry. The reaction highlights the distinct reactivity of the sulfinamide group in Smiles rearrangements versus that of the more common sulfonamides.

Diarylamines are important building blocks in organic synthesis and are present as privileged structures in numerous pharmaceuticals and biologically active compounds. Due to the moiety’s sustained importance to medicinal chemistry, many methods exist for diarylamine synthesis, with transition metal-catalyzed C–N bond formation being especially prominent in recent years.1−3 When the target diarylamine features an electron-deficient arene, a transition metal-free synthesis can be achieved by intermolecular nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr), which remains the third-most-used reaction in medicinal chemistry.4 However, SNAr loses its utility when the substrate’s reactivity is attenuated by steric or electronic constraints or when the target molecule contains multiple reactive sites.

We were interested in harnessing the Smiles rearrangement as a potential route to diarylamines (Scheme 1). Smiles reactions are regiospecific, proceed under mild metal-free conditions, and can be used to construct very sterically hindered systems (Scheme 1A).5 The rearrangement has enjoyed a renaissance in recent years, offering new arylation pathways in both ionic and radical reaction manifolds without recourse to stoichiometric metals and attendant precious metal catalysis. One of the most common substrates utilized in contemporary Smiles chemistry is the sulfonamide6 because it is readily available and provides an entropically driven Smiles pathway via SO2 extrusion.

Scheme 1. Smiles Rearrangements.

Such a reaction could, in principle, be applied directly to diarylamine synthesis from diarylsulfonamides (Scheme 1B). The requisite 3-exo-trig ipso substitution pathway, however, is disfavored,7 and very few examples are known in the Smiles literature for any substrate class.8

There is no precedent for such reactivity with diarylsulfonamides in synthetic chemistry.9 Indeed, the functional group is valued for its stability to base. A single report does describe amine formation from an alkylarylsulfonamide, with Müller reporting the rearrangement of N-benzylnosylamide to the aniline in a low yield after heating to 140 °C in HMPA.10 Interestingly, the transformation is well-documented in the gas phase, with SO2 extrusion being an established fragmentation pathway for sulfonamides in mass spectrometry.11

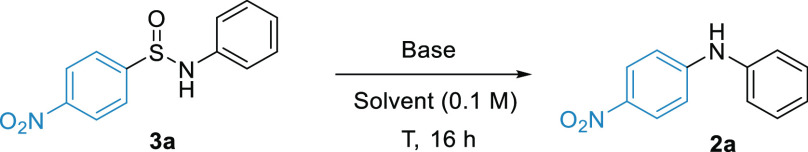

As expected, our initial investigations underlined the difficulty of this transformation with diarylsulfonamides, with sulfonamide 1a (Ar1 = p-NO2C6H5, Ar2 = Ph) failing to produce any diarylamine 2 upon base treatment even under forcing conditions (e.g., excess Cs2CO3 in refluxing DMA). We thus turned our attention to the sulfinamide group as a possible alternative Smiles substrate. Recent work from Nevado and co-workers has demonstrated that sulfinamides are productive in Smiles rearrangements, exploiting the chirality of the S(IV) functionality to achieve challenging stereoselective arylations (Scheme 1C).12 Outside of this work, however, sulfinamides have been underexplored both as substrates in Smiles rearrangements and in synthetic methodology in general. Their current utility is limited mostly to chiral auxiliaries, such as those developed by Davis and Ellman,13,14 or as intermediates in sulfonamide synthesis.15 We were interested in exploring possible reactivity differences between the sulfinamides and sulfonamides in aryl transfer and thus synthesized sulfinamide 3a (Ar1 = p-NO2C6H5, Ar2 = Ph) to study as a potential diarylamine precursor.

We were surprised to find that 3a did indeed produce the diarylamine 2a in good yields upon base treatment under relatively mild conditions such as with K2CO3 in DMF at 60 °C (Table 1, entry 1).

Table 1. Reaction Optimizationa.

| entry | base (equiv) | solvent | T (°C) | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | K2CO3 (3) | DMF | 60 | 54 |

| 2 | DMF | 60 | 0 | |

| 3 | LiOH (6) | DMF | 60 | 74 |

| 4 | Cs2CO3 (3) | DMF | 60 | 74 |

| 5 | NEt3 (3) | DMF | 60 | 0 |

| 6 | LiOH (6) | DMSO | 60 | 70 |

| 7 | LiOH (6) | DMA | 60 | 64 |

| 8 | LiOH (6) | DMF/H2O | 60 | 71 |

| 9 | LiOH (6) | THF | 60 | 7 |

| 10 | LiOH (6) | DMF | 70 | 74 (71)c |

| 11 | Cs2CO3 (6) | DMF | 70 | 74 (73)c |

| 12 | Cs2CO3 (6) | DMA | 70 | 66d |

0.05 mmol scale.

1H NMR yield.

Isolated yield, 0.2 mmol scale.

Microwave heating, 30 min reaction time.

Following an extensive screen of the reaction conditions, we found that the transformation proceeded with most inorganic bases tested, with LiOH and Cs2CO3 performing particularly well (entries 2–5). Furthermore, the rearrangement proceeded in a variety of solvent systems, including with the addition of water as a cosolvent; however, DMF proved the most effective (entries 6–11).

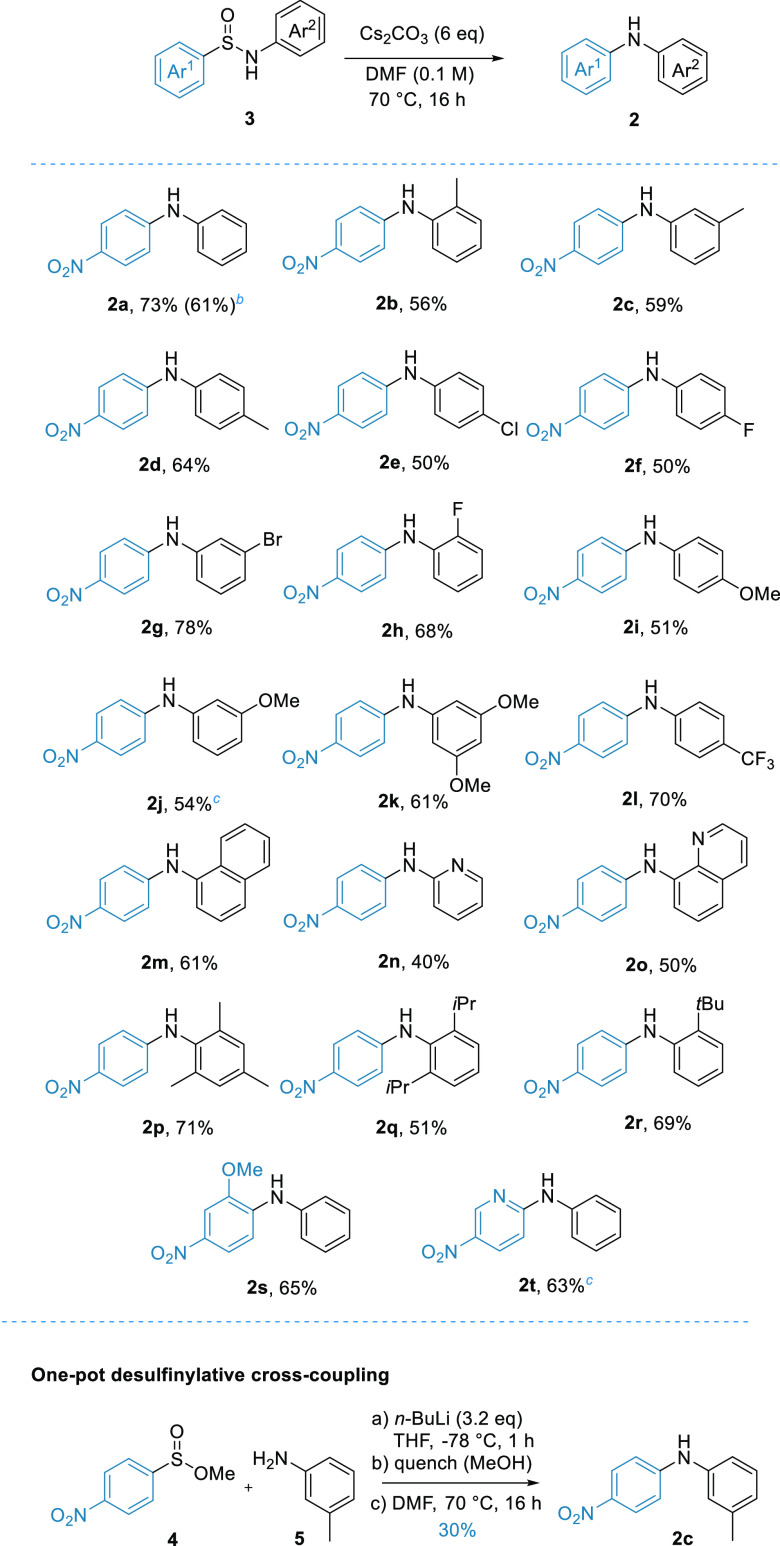

With the reaction conditions in hand, we then looked to examine the substrate scope of the system (Scheme 2). Beginning our investigation with the scope of the N-aryl group, we found that the system was tolerant to simple methyl-substituted rings at all positions (2b–d). Similar success was achieved with halogenated rings 2e–h, which can be challenging to synthesize using transition metal catalysis.

Scheme 2. Substrate Scope.

Isolated yields, 0.2 mmol scale.

1.0 mmol scale.

0.1 mmol scale.

Additionally, the scope encompassed substrates featuring both electron-rich rings (2i–k) and relatively electron-poor ones (2l), although substrates with highly electron-deficient rings were unsuccessful (see the Supporting Information).

Furthermore, the reaction proved effective for alternative arenes, such as the N-naphthyl example 2m, and heterocyclic compounds 2n and 2o. Importantly, and in line with literature precedent for desulfonylative Smiles processes,16 the system proved exceptionally tolerant to highly hindered substrates, affording diarylamines 2p–r. For comparison, the treatment of p-nitrofluorobenzene with the analogous anilines under standard SNAr conditions (K2CO3, DMF, 150 °C, and 16 h) failed to yield any amount of 2p–r. The scope of the sulfonyl component was more restricted, with alternative electron-withdrawing groups such as p-CN, p-Cl, and pentafluoro being unsuccessful in the reaction. We could, however, successfully use an azine heterocycle in the reaction to afford the aminopyridine product 2t. We were also able to develop a one-pot protocol utilizing a solvent swap to synthesize the target diarylamine directly from sulfinate 4 and aniline 5. This result was especially encouraging, as it presented a strategy for a transition metal-free desulfinylative cross-coupling.

We then conducted experiments to elucidate the mechanism of the transformation (Scheme 3). As expected, the corresponding sulfonamide 1a was an ineffective substrate under the optimized reaction conditions, returning only the starting material (Scheme 3A). We further established that N-alkylated substrates were similarly unsuccessful as they also solely afforded the starting material (Scheme 3B), supporting the idea that the deprotonation of the sulfinamide is vital to the reaction. A crossover experiment was then considered to probe possible intermolecular pathways, but the documented rapid exchange between N-aryl sulfinamides in solution17 would prevent a useful interpretation of the results. In view of this, we conducted a competition experiment for the rearrangement of 3a in the presence of 4-methoxyaniline (Scheme 4C). No crossover product was detected, supporting an intramolecular mechanism.

Scheme 3. Mechanistic Investigations.

Scheme 4. Proposed Mechanisms.

We then considered the possibility of thia-Fries-type processes operating in the reaction. This reactivity is well-documented for sulfenamides, sulfinamides, and sulfonamides and can set up a prospective Smiles rearrangement to produce diarylamines (albeit with the C–S bond retained in the products).18,19 The seminal work from Johnson and Moore in 1935, for example, described the rearrangement of ortho-nitrophenylsulfenamide 7 into diarylamine 9 upon treatment with an alcoholic NaOH solution (Scheme 3D).20 The Smiles rearrangement of analogous sulfoxides and sulfones to 8 to give diarylamines is likewise known.21−23 A possible thia-Fries/SO extrusion pathway is illustrated in Scheme 4. To explore this possibility, we synthesized the aryl sulfoxide 10 and exposed it to our reaction conditions (Scheme 3E). No diarylamine product was detected, suggesting this thia-Fries product is not an intermediate in the rearrangement pathway.

Overall, these observations suggest the direct 3-exo-trig Smiles pathway to be the most plausible (A → D, Scheme 4) given the data in hand. While a thia-Fries/Smiles sequence (A → B → C → D) is conceivable and features a standard 5-exo-trig Smiles step, it requires an initial thia-Fries reaction to take place upon mild base treatment that will be dearomatizing in the case of ortho-substituted substrates. The failure of 10 to undergo the reaction, a tautomer of B for unsubstituted cases (R = H), lends further support to the direct 3-exo-trig pathway.

To conclude, we have described a transition metal-free desulfinylative diarylamine synthesis that proceeds under mild conditions and is especially successful in affording highly hindered products that were previously inaccessible by intermolecular SNAr. A preliminary mechanistic survey points to the transformation proceeding via a novel desulfinylative 3-exo-trig Smiles rearrangement, a reactivity not observed with the more common sulfonamide functional group. Further investigations into the aryl transfer reactivity of sulfinamides are underway in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the EPSRC and LifeArc for funding a studentship for T.S. (University of Manchester).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c04122.

Preparative procedures and spectroscopic data for all starting materials and Smiles rearrangement products (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ruiz-Castillo P.; Buchwald S. L. Applications of Palladium-Catalyzed C–N Cross-Coupling Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12564–12649. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-Q.; Li J.-H.; Dong Z.-B. A Review on the Latest Progress of Chan-Lam Coupling Reaction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 3311–3331. 10.1002/adsc.202000495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sambiagio C.; Marsden S. P.; Blacker A. J.; McGowan P. C. Copper catalysed Ullmann type chemistry: from mechanistic aspects to modern development. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 3525–3550. 10.1039/C3CS60289C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G.; Boström J. Analysis of Past and Present Synthetic Methodologies on Medicinal Chemistry: Where Have All the New Reactions Gone?: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4443–4458. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent reviews:; a Holden C. M.; Greaney M. F. Modern Aspects of the Smiles Rearrangement. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 8992–9008. 10.1002/chem.201700353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Henderson A.; Kosowan J.; Wood T. The Truce-Smiles Rearrangement and Related Reactions: A Review. Can. J. Chem. 2017, 95, 483–504. 10.1139/cjc-2016-0594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Allen A. R.; Noten E. A.; Stephenson C. R. J. Aryl Transfer Strategies Mediated by Photoinduced Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2021, 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Huynh M.; De Abreu M.; Belmont P.; Brachet E. Spotlight on Photoinduced Aryl Migration Reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3581–3607. 10.1002/chem.202003507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Whalley D. M.; Greaney M. F. Recent Advances in The Smiles Rearrangement: New Opportunities for Arylation. Synthesis 2021, 10.1055/a-1710-6289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selected recent examples of desulfonylative Smiles rearrangements:; a Whalley D. M.; Seayad J.; Greaney M. F. Truce-Smiles Rearrangements by Strain Release: Harnessing Primary Alkyl Radicals for Metal-Free Arylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 22219–22223. 10.1002/anie.202108240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kang L.; Wang F.; Zhang J.; Yang H.; Xia C.; Qian J.; Jiang G. High Chemo-/Stereoselectivity for Synthesis of Polysubstituted Monofluorinated Pyrimidyl Enol Ether Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 1669–1674. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen F.; Shao Y.; Li M.; Yang C.; Su S. J.; Jiang H.; Ke Z.; Zeng W. Photocatalyzed cycloaromatization of vinylsilanes with arylsulfonylazides. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3304. 10.1038/s41467-021-23326-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Radhoff N.; Studer A. Functionalization of α-C(sp3)–H Bonds in Amides Using Radical Translocating Arylating Group. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3561–3565. 10.1002/anie.202013275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Gillaizeau-Simonian N.; Barde E.; Guérinot A.; Cossy J. Cobalt-Catalyzed 1,4-Aryl Migration/Desulfonylation Cascade: Synthesis of α-Aryl Amides. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 4004–4008. 10.1002/chem.202005129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wang Z. S.; Chen Y. B.; Zhang H. W.; Sun Z.; Zhu C.; Ye L. W. Ynamide Smiles Rearrangement Triggered by Visible-Light-Mediated Regioselective Ketyl–Ynamide Coupling: Rapid Access to Functionalized Indoles and Isoquinolines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3636–3644. 10.1021/jacs.9b13975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Yan J.; Cheo H. W.; Teo W. K.; Shi X.; Wu H.; Idres S. B.; Deng L. W.; Wu J. A Radical Smiles Rearrangement Promoted by Neutral Eosin Y as a Direct Hydrogen Atom Transfer Photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11357–11362. 10.1021/jacs.0c02052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Alpers D.; Cole K. P.; Stephenson C. R. J. Visible Light Mediated Aryl Migration by Homolytic C–N Cleavage of Aryl Amines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 12167–12170. 10.1002/anie.201806659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Barlow H. L.; Rabet P. T. G.; Durie A.; Evans T.; Greaney M. F. Arylation Using Sulfonamides: Phenylacetamide Synthesis through Tandem Acylation-Smiles Rearrangement. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9033–9035. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Monos T. M.; McAtee R. C.; Stephenson C. R. J. Arylsulfonylacetamides as bifunctional reagents for alkene aminoarylation. Science 2018, 361, 1369–1373. 10.1126/science.aat2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss D.; Wu Y.; Grossi M.; Hollett J.; Wood T. Effect of the tether length upon Truce-Smiles rearrangement reactions. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2018, 31, e3742. 10.1002/poc.3742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a El Kaim L.; Grimaud L.; Le Goff X. F.; Schiltz A. Smiles Cascades toward Heterocyclic Scaffolds. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 534–536. 10.1021/ol1028817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yang J.; Guo Y.; Wang J.; Dudley G. B.; Sun K. DFT study on the reaction mechanism and regioselectivity for the [1,2]-anionic rearrangement of 2-benzyloxypyridine derivatives. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 4451–4457. 10.1016/j.tet.2019.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For the double Smiles rearrangement of sulfonamides, see:; a Kleb K. G. New Rearrangement of the Smiles Reaction Type. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1968, 7, 291–291. 10.1002/anie.196802911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yang D.; Xie C. X.; Wu X. T.; Fei L. R.; Feng L.; Ma C. Metal-Free beta-Amino Alcohol Synthesis: A Two-step Smiles Rearrangement. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 14905–14915. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P.; Phuong N.-T. M. ipso-Substitution with Sodium-N-alkyl-(p-nitrobenzene)sulfonamide. A Novel Anionic Rearrangement. Helv. Chim. Acta 1979, 62, 494–496. 10.1002/hlca.19790620215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.; Dai W.; Liu D. Q. Fragmentation of aromatic sulfonamides in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: elimination of SO2 via rearrangement. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 43, 383–393. and references therein 10.1002/jms.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu C.; Kirillova M. S.; Suárez T.; Müller M.; Merino E.; Nevado C. Asymmetric, visible light-mediated radical sulfinyl-Smiles rearrangement to access all-carbon quaternary stereocentres. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 327–334. 10.1038/s41557-021-00668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis F. A. Adventures in Sulfur–Nitrogen Chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8993–9003. 10.1021/jo061027p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Cogan D. A.; Ellman J. A. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of tert-Butanesulfinamide. Application to the Asymmetric Synthesis of Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 9913–9914. 10.1021/ja972012z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko E. S.; Markovskii L. N.; Shermolovich Y. G. Chemistry of sulfonimide acids derivatives. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 36, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfand E.; Forslund L.; Motherwell W. B.; Vázquez S. Observations on the Enforced Orthogonality Concept for the Synthesis of Fully Hindered Biaryls by a Tin-Free Intramolecular Radical Ipso Substitution. Synlett 2000, 2000, 475–478. 10.1055/s-2000-6577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke V.; Cole E. R. Sulfenamides and Sulfinamides IX Exchange Reactions of Aryl Sulfinamides. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon and the Related Elements 1994, 92, 45–50. 10.1080/10426509408021456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K. K.; Malver O. Substitution at tricoordinate sulfur(IV). Rearrangement of sulfinanilides to anilino sulfoxides. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 4803–4807. 10.1021/jo00173a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer S. J.; Closson W. D. Base-promoted rearrangement of arenesulfonamides of N-substituted anilines to N-substituted 2-aminodiaryl sulfones. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 889–892. 10.1021/jo00895a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. B.; Moore M. L. Molecular Rearrangements of Sulfanilides. Science 1935, 81, 643–4. 10.1126/science.81.2113.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa T.; Hosoya T.; Yoshida S. Transition-Metal-Free Synthesis of N-Arylphenothiazines through an N- and S-Arylation Sequence. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 2347–2352. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W. J.; Smiles S. A rearrangement of o-acetamido-sulphones and -sulphides. J. Chem. Soc. 1935, 181–188. 10.1039/jr9350000181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwinkel D.; Lenz R. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der anionisch induzierten Sulfonamid-Aminosulfon-Umlagerung. Chem. Ber. 1985, 118, 66–85. 10.1002/cber.19851180108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.