For the past 2 years the world's attention has rightly been focused on COVID-19, the most lethal pandemic seen for over a century that has amplified the enormous global toll of respiratory tract infections. COVID-19 remains the top cause of death from an infectious disease worldwide, shifting tuberculosis to second place.1 In areas highly endemic with tuberculosis, scarce resources have been moved to the COVID-19 response, which has undermined tuberculosis testing and treatment programmes. The effects of COVID-19 on global tuberculosis control efforts have been catastrophic,1, 2, 3 setting back by several years any progress being made in achieving the WHO End TB Strategy targets by 2030.4 For the first time since 2015, the annual numbers of tuberculosis deaths have started increasing and more than 1·5 million people died of tuberculosis in 2020.1 Furthermore, COVID-19 disruptions to health services have impeded diagnosing and treating everyone with active tuberculosis, drug-resistant tuberculosis, multidrug-resistant or extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, latent tuberculosis, and tuberculosis and HIV co-infection, as well as access to tuberculosis medicines, counselling and follow-up, and lowered treatment adherence.1,3–7 This impedance in turn promotes the development of multidrug-resistant strains of tuberculosis and increases treatment failure rates, suffering, and death. Thus, in the foreseeable future, tuberculosis will continue to pose multiple challenges and negatively impact on already fragile health systems in countries with a high burden of tuberculosis.

The theme for this year's World Tuberculosis Day is “Invest to End TB. Save Lives'”. Although this theme is appropriate to refocus attention from COVID-19 to tuberculosis, it is a difficult task to achieve. The call for donors to invest more to end tuberculosis is again sadly familiar, yet essential because strategies for holding governments accountable and that advocate for increased investments have been in place ever since WHO declared tuberculosis a global emergency in 1993.8 It is unlikely that in light of the poor global economic situation, major financial commitments to global tuberculosis control programmes will be forthcoming. However, while the tuberculosis community awaits financial commitments, despair can be turned to hope through more creative and innovative ways of health services delivery.

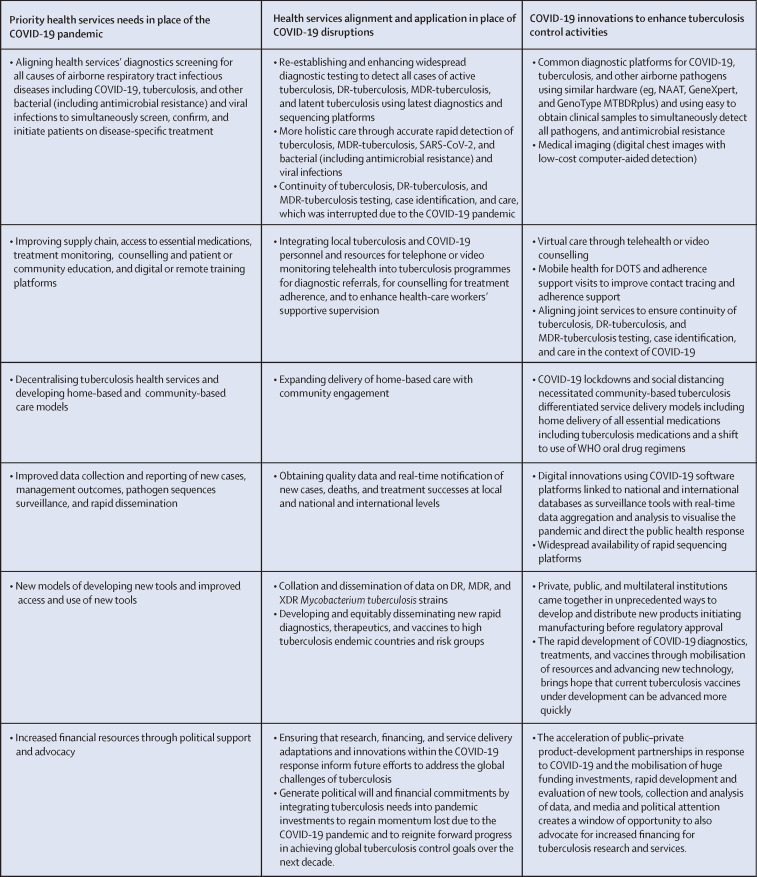

We already have all the tools required to achieve global tuberculosis control targets,8, 9, 10 and much more can be achieved via new ways of working, innovative strategies, and using existing resources maximally. Over the past 2 years, several promising new developments in approaches to screening, diagnosis, and management for both tuberculosis and COVID-19, if skilfully used, aligned, and synergised, could overcome the negative effects of COVID-19 disruptions in health services for airborne infectious diseases. Several lessons learnt from COVID-19 responses, including innovative new ways of health services working,3,5–7 also provide a fresh approach to management of respiratory infectious diseases with overlapping clinical symptoms and signs. Several practical steps, using recently updated diagnostics, treatments, patient follow-up, and community care guidelines for both COVID-19 and tuberculosis,6, 7, 8, 9, 10 if immediately taken forward, could have a synergistic, enhancing, and multiplier effect. Thus, COVID-19 programme innovations and adaptations from within the COVID-19 response should be built upon, to enhance access to integrated, patient-centred tuberculosis services (figure ).3, 5, 6, 7

Figure.

Advancing COVID-19 innovations to end tuberculosis

DOTS=directly observed therapy short course. DR-tuberculosis=drug-resistant tuberculosis. MDR-tuberculosis=multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. NAAT=nucleic acid amplification test. XDR=extensively drug-resistant.

The ongoing COVID-19 mass testing and vaccination rollout in wealthy nations are the result of unprecedented financial investments, rapid research and development, collaborative science, and innovation in delivery systems. Diseases that affect wealthier nations receive immediate attention and the required funding is made available quickly. However, the history of tuberculosis, and now COVID-19, is one of scientific and medical advances, accompanied by political failure to invest appropriately in rolling them out to all in need. The issues of inequities in COVID-19 vaccine distribution to Africa and unfulfilled pledges by wealthier nations, highlights that more visionary leadership, coupled with serious investments, are required from national governments to make countries with a high burden of tuberculosis self-reliant. Continued disinvestments in Africa into both tuberculosis and COVID-19 resulting from lack of political will is unacceptable.

Countries that are highly endemic for tuberculosis have all the experience and knowledge on social, economic, and operational determinants that drive the tuberculosis epidemic. There is an urgent need for countries that are highly endemic with tuberculosis to move away from donor dependency and invest in resilient and sustainable health systems. This would provide reassurance to all tuberculosis stakeholders in this unprecedented COVID-19 era of uncertainty. Tuberculosis-endemic countries should focus on revamping health services, recalibrating them, and making the health sector more inclusive of all other WHO-declared global emergencies. The time is also now ripe for countries endemic with tuberculosis to build goodwill on the current global attention on COVID-19 to better address existing tuberculosis care models, One Health approaches to prevent future zoonotic pandemics and the burgeoning problem of global antimicrobial resistance.

© 2022 Flickr/PWRDF

KGC declares salary support to serve as US Agency for International Development (USAID) senior tuberculosis scientific advisor through an intergovernmental personnel act award between Emory University and USAID. AZ, FN, and DY-M acknowledge support from the EU-EDCTP funded PANDORA-ID-NET, CANTAM-3, and EACCR-3 programmes. AZ is in receipt of a UK National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator Award. JBN acknowledges support from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Fogarty International Center (grants 1R25TW011217-01, 1R21TW011706-01, and 1D43TW010937-01A1) and NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant U01 AI096299). All other authors declare no competing interests. All authors have a specialist interest in global epidemics of COVID-19, tuberculosis, and HIV. The views expressed in this editorial are entirely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of their respective institutions.

References

- 1.WHO Global tuberculosis report 2021. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021

- 2.Wu Z, Chen J, Xia Z, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the detection of TB in Shanghai, China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2020;24:1122–1124. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pai M, Kasaeva T, Swaminathan S. Covid-19's devastating effect on tuberculosis care – a path to recovery. N Engl J Med. 2022 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2118145. published online Jan 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO The End TB strategy. Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after. 2015. https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/the-end-tb-strategy

- 5.Hopewell PC, Reichman LB, Castro KG. Parallels and mutual lessons in tuberculosis and covid-19 transmission, prevention, and control. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:681–686. doi: 10.3201/eid2703.203456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman HJ, Veras-Estévez BA. Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic to strengthen tb infection control: a rapid review. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;9:964–977. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruhwald M, Carmona S, Pai M. Learning from COVID-19 to reimagine tuberculosis diagnosis. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2:e169–e170. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marais BJ, Raviglione MC, Donald PR, et al. Scale-up of services and research priorities for diagnosis, management, and control of tuberculosis: a call to action. Lancet. 2010;375:2179–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treatment Action Group 2021 Pipeline Report. 2021. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/resources/pipeline-report/2021-pipeline-report/

- 10.United States Agency for International Development and Stop TB Partnership . Stop TB Partnership; Geneva: 2021. Implementation of simultaneous diagnostic testing for COVID-19 and TB in high TB burden countries. [Google Scholar]