Abstract

We investigate how the lockdown enforcement by French authorities is associated with the resolution of corporate insolvency. In this sense, we make a distinction between four legal procedures, namely the amicable liquidation (out-of-court exit), the judicial liquidation (court-driven exit), the restructuring procedure available to non-defaulted firms, and the restructuring procedure available to defaulted firms. Using a sample of 3488 non-listed and non-financial French firms, our estimates yield three major findings. First, the likelihood of judicial liquidation increased after the lifting of the quarantines compared to the pre-pandemic period. Second, the non-defaulted firms had a higher likelihood to reorganize in court during the second lockdown. Third, the lifting of the first lockdown led to a decrease in the probability of restructuring the assets of defaulted firms. Although the main objective of the lockdown was to limit spread of the virus, its enforcement has not encouraged the use of the out-of-court exit path.

Keywords: Covid-19, Lockdown, Bankruptcy, Reorganization, Liquidation, Firm

1. Introduction

High levels of COVID-19 infection obliged local authorities across the world to impose social distancing and quarantine measures. As firms were temporarily confronted with low or nonexistent demand, the risk of mass bankruptcies overshadowed entire economies. Demmou et al.’s (2021) analysis on OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries indicated a decline in firms’ profits ranging from 40% to 50% as a result of the COVID-19 shock. Most notably, it was predicted that an expected percentage of 7–9% of viable firms would be subject to financial distress with a negative book value on equity, whereas around one-third of firms would be unable to cover interest expenses (Demmou et al., 2021). In the context of a not only a 15% drop in the volume of goods and services traded but also an estimated decrease of 3.3% of the global gross domestic product, the insurance company Euler Hermes predicted a strong global wave of bankruptcies due to the pandemic in May 2020 with an expected rise of bankruptcies by 25% in United States and 19% in Europe.

Surprisingly, bankruptcies appeared to slow down in some countries during the lockdown period. According to the United Kingdom’s (UK) Insolvency Service, the daily number of compulsory liquidations decreased by 80% in May 2020 compared with the prelockdown period of March 2020. Additionally, 944 cases of corporate insolvencies were reported in May 2020 in England and Wales, which was 30% less than those in the same month of the previous year. The American Bankruptcy Institute also confirms an average decrease of 25.1% in business filings for the period from April 2020 to June 2020 compared with those during the same period in 2019. The first lockdown was enforced in France from March 17, 2020, to May 10, 2020, during which French business insolvencies decreased by 63% in April 2020 compared with those in February 2020, while the average decrease over the year was 19.1% for April 2020 (Banque de France). How were such reductions possible? Following the explanations of the UK’s Insolvency Service, bankruptcy institutions were forced to reduce capacity to establish new work conditions to safeguard their employees’ health. Moreover, documents provided by British insolvency practitioners suffered from long delays. Federal courts in the United States and French commercial courts were temporarily closed to the general public, and their activities were managed through online services. On a different note, Castelliano et al. (2021) emphasized that the pandemic also affected the labor courts leading to a considerable decrease in the clearance rate and an increase in court backlogs. Despite these impediments, some firms still managed to leave the market during the lockdown and post-lockdown periods, as the accumulation of debt and decreases in liquidity led to a rise in immediate liabilities and decrease in available assets, raising the payment default risk.

Some studies have also raised the potential issue of increased bankruptcies that could be caused by the health crisis (Carletti et al., 2020, Demary, 2021, Didier et al., 2021, Liu et al., 2021). Battiston et al. (2007) asserted that a bankruptcy boom is favored by long delayed payments (trade credits) and additional costs generated by failures in supply. Similarly, Jacobson and Von Schedvin (2015) argued that trade debtor failures increase the bankruptcy risk of trade creditors, leading to an avalanche of corporate failures. Such elements can be found in the context of COVID-19. Hence, effectively addressing corporate insolvency during the pandemic periods is a question of considerable importance in bankruptcy literature. Our study aims to answer that question by shedding light on how lockdown measures correlate with firms’ institutional path to the resolution of insolvency. In this sense, we investigate the French insolvency framework that provides multiple legal procedures, such as amicable liquidation (out-of-court exit); judicial liquidation (court-driven exit), a reorganization procedure for non-defaulted firms (sauvegarde); and a restructuring procedure for firms in payment default (redressement judiciaire). Using a sample of 3488 nonfinancial firms, we examine the consequences of the two quarantines enforced by French public authorities in 2020 on the firms’ likelihood to engage in one of these institutional paths.

Corporate failure is driven by various factors ranging from financial features (Lennox, 1999) to subcontracting relationships (Doi, 1999), business maturity (Pérez et al., 2004), macroeconomic instability (Bhattacharjee et al., 2009), debt cost (Bottazzi et al., 2011), founders’ experience (DeTienne and Cardon, 2012), directors’ independence (Hsu and Wu, 2014), firm-specific uncertainty (Byrne et al., 2016), new firm formation (Stef and Jabeur, 2018, Jabeur et al., 2021), difficulty of firing (Stef, 2018), legal form (Iwasaki and Kim, 2020), legal reform (Bose et al., 2021), and institutional quality (Stef, 2021). A detailed typology of the causes of bankruptcy was initially developed by Blazy et al. (2013), proposing seven types of default causes, including strategy, production, finance, management, outlets, accident, and external environment. Their analysis demonstrated that the major causes of corporate bankruptcy in France and the UK are primarily poor quality products, high price strategy, and/or disappearance of customers (outlets). In the case of legal restructuring, external environment appeared to be the second most frequent cause of firms defaulting. Similarly, Blazy and Stef (2020) reported the impact of external environment as one of the principal causes of bankruptcy in Hungary, Poland, and Romania. In their investigation, causes related to the external environment included exchange rate fluctuations, increase in competition, or credit crunch periods, as well as events of force majeure (e.g., war, political crisis, or natural catastrophe). A new component of firms’ external environment is the global spread of COVID-19. In this framework, our study will address the relevance of public health lockdown measures as determinants of firms’ failure for the first time.

We organized the remainder of our study into the following four sections. Section 2 provides an overview of France-specific institutional paths to insolvency resolution (subsection 2.1), presents the specificities of the French lockdown, discusses the incentives for firms to leave the market during the pandemic crisis (subsection 2.2), and examines the attractiveness of these paths for (non)defaulted firms confronted with the COVID-19 pandemic (subsection 2.3). Data and the empirical analysis are presented in 3, 4, respectively. The final section highlights and discusses the major results of our study.

2. Resolution of corporate insolvency and the pandemic crisis

2.1. Insolvency framework of France

French bankruptcy code includes an array of procedures aimed at addressing corporate financial failure.1 The use of an insolvency proceeding depends on the capacity of the debtor (firm) to honor its financial obligations. A firm that is unable to meet its commitments within a period of 45 days is considered to be in suspension of payment. Consequently, the debtor can settle the creditors’ claims through one of the two procedures, namely, judicial liquidation or the redressement judiciaire (judicial restructuring) procedure. The path of judicial liquidation is pronounced by the Commercial Court or Judicial Court, depending on the location of business activity. Initiating this procedure requires not only the firm’s payment default but also the impossibility to restore the financial health of the business through a restructuring procedure. A bankruptcy practitioner is appointed by the competent court to terminate the firm’s activity by selling its assets to settle the creditors’ claims. The closing of judicial liquidation is pronounced by the court when liabilities are no longer due, the creditors’ claims are fully satisfied, or the continuation of the procedure is prevented by a lack of assets.

Conversely, the redressement judiciaire procedure is a restructuring tool, including three main objectives, which are the debtors’ survival, preservation of employment, and creditors’ reimbursement. When the procedure is triggered, the debtor is subject to an observation period, which cannot exceed 18 months, during which the debtor and administrator appointed by the court must identify solutions for achieving the three main objectives. According to Blazy et al. (2013), the observation period grants a stay of claims, during which managers can maintain their positions with the help of the administrator. If the firm’s restructuring is doomed to fail, the court can convert the redressement judiciaire procedure into a judicial liquidation.

The French bankruptcy code also provides procedures to firms that are not confronted with a default of payment. In this sense, some bankruptcy codes can rely upon different liquidation procedures. For instance, the insolvency code of the UK provides three types of procedures, including compulsory liquidation, the creditors’ voluntary liquidation, and members’ voluntary liquidation (Blazy et al., 2013). The first two procedures can be enforced when a debtor is unable to fully repay debts, while the last procedure can be triggered when shareholders holding sufficient assets are willing to dissolve their own firms to cover the creditors’ claims. Similarly, the French bankruptcy system relies on a liquidation procedure known as amicable liquidation. The procedure results from a voluntary decision made by the owners (shareholders), who must vote for the early dissolution of the company at an extraordinary general meeting. It can be triggered as long as the interests of a firm’s creditors are not harmed. Therefore, the assets’ values must cover the liabilities so that creditors are fully reimbursed at the end of the procedure. After establishing an inventory, the liquidator, who is appointed by the owners, proceeds to sell the assets and then discharge the debts. The primary objective is not to pay off creditors but to put an end to a firm’s operations by releasing its residual assets. This procedure can be a tool for restructuring companies, as the remaining assets can be reinvested, reallocated to new activities, or redistributed to the partners; however, if the proceeds from selling a firm’s assets are not sufficient to cover the liabilities and creditors are unwilling to accept a lower reimbursement, a firm must follow the path of a court-driven exit (Ponikvar et al., 2018).

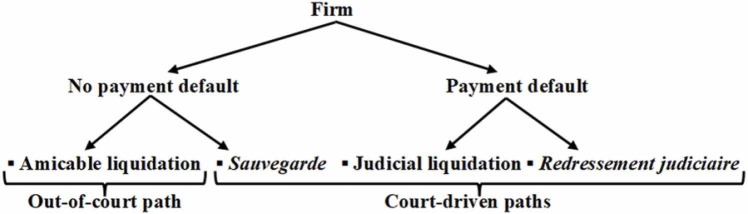

Nevertheless, firms that are not subject to payment suspension but to financial difficulties can initiate a restructuring procedure known as sauvegarde procedure.2 As in the case of redressement judiciaire, the procedure aims to restore the firm’s financial health and preserve employment; however, the maximum length of the observation period is 12 months and the manager that retains their position must propose a restructuring plan. The financial measures included in the plan must be accepted by the creditors through voting. If the firm’s cessation of payment occurs during the execution of the plan, the court can convert the sauvegarde procedure into either a judicial liquidation or redressement judiciaire procedure. Fig. 1 presents an overview of a firm’s institutional path to insolvency resolution.

Fig. 1.

Institutional paths to resolution of inslovency.

2.2. Failure risk and the COVID-19 pandemic

2.2.1. Specificities of the French lockdown

Following the rise of COVID-19 infections at the beginning of 2020, the French government enforced its first lockdown on March 17, 2020, which lasted until May 5, 2020. Unfortunately, lifting the first lockdown did not inhibit the spread of the virus, leading to a second lockdown from October 30, 2020, to December 14, 2020. Those two lockdowns imposed two major restrictions. First, individuals were obliged to follow social distancing rules that limited movement outside of their homes. Exceptions to these rules were applied for those seeking to go to work, to a medical appointment, to purchase goods of basic necessity, to walk near their homes for an hour, or to attend a judicial summon. Second, businesses that were not essential to the functioning of the national economy were forced to temporarily close. The only entities that remained opened were food shops, essential public institutions, banks, pharmacies, and gas stations.

These restrictions placed strong pressure on firms’ capacity to remunerate employees and to honor fiscal obligations. Consequently, the French government decided to provide some public support to the private sector.3 First, firms subject to financial difficulties had the option to defer the payment of social contributions and direct taxes. Second, a public program of state guaranteed loans, aimed to strengthen the liquidity of firms, was launched at the beginning of the first lockdown. This device allowed all firms, except for real estate and financial firms, to benefit from a state-guaranteed loan amounting to 3 months of 2019 turnover, or two years of payroll for innovative or young firms. These loans did not require a reimbursement in the first year. Third, firms confronted with a reduction in activity could apply for a program addressing long-term partial activity that granted an allowance to employees for their nonworking hours.

In the context of the pandemic, a short-term bankruptcy reform was also adopted by the French authorities, which impacted owners’ incentives to file for a liquidation procedure. According to the French commercial code, a cessation of payments must be declared to the court within a period of 45 days that will decide the settlement procedure of a firm’s debt. In the context of COVID-19, a new order was enacted by the French government that (1) granted the right to file for bankruptcy only to debtors, (2) permitted an assessment of the cessation based on firm’s financial health as reported on March 12, 2020—just four days before the first lockdown start date, and (3) encouraged the use of preventive bankruptcy procedures by firms facing payment cessation after March 12.4 Hence, the new governmental order provided debtors the opportunity to decide when to exit during the periods of lockdown and post-lockdown. In this new context, firms that engaged in judicial liquidation procedures were probably businesses with extremely low chances of financial recovery; however, it can also be speculated that lockdown established a context that encouraged debt renegotiation, leading to the out-of-court exit or reorganization path. Our research seeks to explore this framework for the first time in bankruptcy literature by examining the association between lockdown enforcement and the likelihood of triggering a bankruptcy procedure.

2.2.2. Global strategies to face the pandemic crisis

One of the most severe consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic was the imposition of lockdowns, representing a public health strategy aimed at hampering the virus spread. During lockdowns, individuals are subject to self-isolation and travel restrictions, while firms are forced to temporarily close. Such an environment limits consumption, as individuals tend to pursue their basic needs, i.e., food and health, to the detriment of other secondary needs. Consequently, firms need to react and adapt to the new market conditions emerging from the viral contagion. In this sense, Wenzel et al. (2020) identified four potential strategic responses of firms to the current crisis, namely, retrenchment by managing reductions in costs and assets, persevering with measures to maintain business activities, innovating based on strategic renewal, and exit through the discontinuation of operational activities. Failures in the first three responses can lead to a firm’s dissolution. Moreover, failure risk might increase during a longer period of lockdown, which completely inhibits a firm’s sales as customers are confronted with self-isolation. In this sense, Carletti et al. (2020) examined the potential financial impact of lockdown duration using a sample of 80,972 Italian firms. Not surprisingly, their empirical analysis forecasted that a three-month lockdown would lead to an aggregate yearly drop in profits, amounting to 10% of the national GDP and to the financial distress of 17% of the sample firms.

According to Kraus et al. (2020), the strategic responses of family firms to the COVID-19 crisis were triggered by the following two main motivations: safeguarding liquidity and improving the firm’s long-term survival. The second motivation can be accomplished if the firm remains on the market; therefore, owners’ key motivation seems to be maintaining a degree of liquidity that can allow for the coverage of their fixed costs at the least. In this sense, Didier et al. (2021) suggested the term hibernation to describe the use of a bare minimum amount of cash by firms facing social distancing measures and pandemic lockdown. Such cash should be used to adjust operational activities and freeze a firm’s relationship with stakeholders. However, the hibernation period may depend on liquidities that a firm was holding prior to the enforcement of a national quarantine.

Some evidence of COVID-19′s impact on liquidity was presented by De Vito and Gómez (2020). Using a sample of 14,245 listed firms from 26 countries, their empirical analysis indicates that a drop in sales by 50% and 75% for firms with partial flexibility would lead to an average increase of short-term liabilities ranging from 216.01% to 779.26%, respectively. Moreover, a larger contraction in demand would render 10% of firms illiquid within 6 months. Miyakawa et al. (2021) examined the exit rate of Japanese firms under several assumptions. First, firm exits potentially increased by 20% compared with the pre-pandemic period, assuming that the temporary reduction in sales was anticipated by firms. Second, the increase in exit rates amounts to almost 110% if sales reduction fully impacted firms’ expectations for future sales. As pointed out by Famiglietti and Leibovici (2020), the virus spread harmed firms’ revenues and tightened access to external finance; hence, firms with high levels of cash or fluid access to funding should more easily cover large expenditures related to wages and overhead costs. Famiglietti and Leibovici (2020) also argue that firms with less liquidity and more debt are more prone to bankruptcy given the inability to meet short-term financial obligations and limited access to external finance.

Overall, the pandemic crisis has put pressure on firms’ capacity to use internal resources and attract additional funds. Such behavior is primarily explained by the drop in demand due to the state of quarantine and firms’ operational functioning in the stage of hibernation. Following Famiglietti and Leibovici (2020), the exit path as a response to COVID-19 outbreak should have been followed by firms holding less liquidity and/or more debt prior to lockdown enforcement. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Amankwah-Amoah et al. (2021) argued that business failure is more likely for firms that lack the capacity to quickly alter their business model in favor of a new routine that facilitates adaptation to the practice of social distancing and adherence to governments’ new directives. Moreover, their study asserts that the risk of corporate failure is likely to increase as authorities cannot rely upon the best practices to guide policy interventions during the pandemic. If such failure is imminent, the question of which institutional path a firm should follow arises.

2.3. How can insolvency be resolved in a pandemic?

As the French government temporarily granted debtors the exclusive right to trigger judicial liquidation during the pandemic, a relevant question is which insolvency resolution path is suitable for firms facing financial difficulties. White (1980) noted that the continuation of business activity should be encouraged when the present value of future earnings resulting from a firm’s survival is higher than the liquidation value of assets. However, the COVID-19 crisis left firms with very limited cash reserves and induced severe losses to shareholders that would act as residual claimants of a firm’s assets in case of bankruptcy (Liu et al., 2021). Moreover, Altig et al. (2020) argued that the COVID-19 crisis led to massive uncertainty across multiple considerations, such as the duration of social distancing, changes in consumer spending patterns, the speed of economic recovery, travel restrictions, and the impact on business formation. Hence, the pandemic is assumed to have diminished the value of future earnings, biasing the path of a financially distressed firm toward potential liquidation.

In the landscape of French law, amicable liquidation is an exit path subject to the shareholders’ discretion, whereas initiating judicial liquidation addresses the debtor’s legal obligation, resulting from a severe shortage of assets. In the shadow of the pandemic crisis, the use of amicable liquidation can allow the formation of new firms, as existing managers and partners may be able to allocate the liquidation surplus generated by the procedure to an activity that they plan to conduct in the postcrisis period. Linnenluecke and McKnight (2017) noted that natural disasters open business opportunities that can encourage entrepreneurs to create value. Nevertheless, amicable liquidation requires that the firm is not confronted with a payment default and that all creditors are satisfied with the amount of their reimbursement. The achievement of these two conditions seems to be hampered by the liquidity crisis induced by COVID-19. Nonfinancial businesses largely drew funds from bank credit lines, anticipating disruptions in cash flow and an extreme deterioration of funding conditions (Li et al., 2020). Guerini et al. (2020) suggested that the lockdown enforcement produced an unprecedented increase in the share of illiquid firms, from 3.8% to almost 10%, based on a sample of about one million French nonfinancial companies. Therefore, the pandemic crisis is conjectured to have reduced firms’ capacity to settle their debts in full in order to pursue the path of amicable liquidation, favoring the use of the court-driven exit. A higher likelihood of judicial liquidation is expected during the pandemic periods, captured either by the lockdown or post-lockdown periods.

However, Brown (1989) argued that a set of mutually advantageous reorganization plans are available to firms facing financial distress. The prospect of business reorganization should be more attractive to stakeholders when the liquidation of assets generates high losses and creditors can receive a low degree of reimbursement. In the context of the pandemic, lockdowns imposed a temporary shutdown of business activities and restrictions on consumers’ behavior. Didier (2021) suggested that firms’ survival could be favored by hibernation, characterized as the adjustment of operational activities to a reduced capacity. Because firms depend on key relationships with some stakeholders (employees, customers, local authorities, and creditors), business survival also requires that all of these stakeholders share the burden of the firm’s reduced activity until the pandemic is overcome. Similarly, Stef (2015) showed that a firm’s survival is favored by plans that share the costs of reorganization between the debtor and creditors.

In this situation, why should reorganization be an attractive legal path during the pandemic? The French restructuring procedures (sauvegarde and redressement judiciaire) can be useful mechanisms to support a firm’s hibernation, during which the debtor, along with the creditors and bankruptcy administrator, can identify efficient solutions to adapt business operations to the new environment. According to Le and Phi (2021), a hibernation strategy that includes the minimization of operations and a reduction in salaries should be followed by a recovery phase addressing business innovation and policies aimed at recovering customers. However, the consensus needed for reorganization can be hampered by conflicts between unsecured creditors and well-secured creditors (Bergström et al., 2002). A collateral value closer to the value of the claim can encourage some creditors to oppose the firm’s reorganization. Such conflicts are overcome by the French bankruptcy code because creditors only vote for the approval of the restructuring plan, while the relevant court can enforce the plan or a modified version of the plan, even when creditors initially reject the plan (Blazy and Chopard, 2012). Thus, the content of the plan must convince only the judge for a firm to legally restructure its activities. Overall, a higher likelihood of firms’ restructuring through sauvegarde or redressement judiciaire procedures can be expected during the pandemic periods.

Firms have also benefited from public measures adopted by the French government during the pandemic, including addressing the deferment of social contributions, state-guaranteed loans, and wage compensations due to activity reductions. According to the OECD (2021), countries that relied more on financial subsidies and temporary changes than insolvency procedures were able to reduce the use of bankruptcy at national levels. As argued by Cros et al. (2020), the public measures adopted by the French state can explain the slowdown of bankruptcy filings by small- and medium-sized enterprises, which decreased by 29% by mid-November 2020 compared with those in 2019. By providing financial protection to firms and employees, the public policies might have diminished the attractiveness of bankruptcy procedures that are recognized to have a higher degree of debtor friendliness (Blazy et al., 2018). Moreover, policy intervention that encourages firms’ survival, rather than operational restructuring may lead to business hibernation (Didier et al., 2021). Hence, the use of bankruptcy procedures (restructuring or liquidation) is expected to be negatively impacted by the pandemic periods.

3. Data and variables

We have used the DIANE database of Bureau van Dijk to identify nonfinancial French firms that were subject to a legal procedure between January 1, 2019, and March 31, 2021. In this database, we have identified 4334 firms that were voluntarily dissolved through an amicable liquidation, 6401 firms that were liquidated in court, 395 firms that triggered a sauvegarde procedure, and 1030 firms that followed a redressement judiciaire procedure.5 The final sample is composed of 3448 firms that reported balance sheets and financial income statements one year prior to the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings. For firms that engaged on a bankruptcy path between January 1, 2020, and March 31, 2021, we used the financial data available for 2019, while the financial data available for 2018 was used for the other firms. It should be noted that our sampling approach has two major limitations. First, our empirical analysis relies only on firms that triggered a bankruptcy procedure, and thus, excluded healthy firms that maintained their operations. Second, firms with missing accounting data were not included in our final sample; however, the lack of financial data can be associated with a sign of financial distress. Additionally, we restricted our bankruptcy analysis on the primary forms of firms’ default resolutions without considering insolvency procedures that resulted from the conversion of other procedures.

Overall, we kept 29.33% of the amicable liquidation sample composed of 4334 firms, 23.09% of the judicial liquidation sample based on 6401 firms, 56.71% of the sauvegarde sample composed of 395 firms, and 46.12% of the redressement judiciaire sample, which included 1030 firms. Nevertheless, Blazy and Stef (2020) recommended that the sampling method must be close to actual distribution at the national level. According to Altares D&B, the number of judicial liquidations represented 67.6% of the total number of court-driven procedures in 2019 and 72.5% in 2020, the redressement judiciaire procedures represented 30.5% in 2019 and 25% in 2020, and the sauvegarde procedures accounted for 1.9% in 2019 and 2.6% in 2020.6 In our sample, the distribution of judicial liquidation procedures is 59.8% of the total number of court-driven procedures in 2019 and 71.5% in 2020, whereas the redressement judiciaire procedure represents 29.6% in 2019 and 17.9% in 2020. Overall, the distribution of court-driven procedures is close to the distribution of procedures at national level, with the exception of the sauvegarde procedure that has a large weight (10.6% in 2019 and 10.5% in 2020). However, we have decided to keep all of the observations for the sauvegarde procedure because the application of the national weights would lead to the use of 65 firms instead of 224 firms.

Fig. 2 presents the distribution of our sample according to four major pandemic periods that were enforced by French public authorities, namely, the period of the first lockdown (First Lockdown), the period between the first and second lockdown (First Post-lockdown), the period of the second lockdown (Second Lockdown), and the period after the second lockdown (Second Post-lockdown).7 Almost 20.2% of sample firms were liquidated during the period between the two lockdowns, which accounts for nearly six months. Among the periods studied, about 39% of corporate restructuring occurred during that period. The lifting of the lockdown implied not only the cessation of travel restrictions for individuals but also the reopening of the French commercial courts in charge of administering bankruptcy procedures.

Fig. 2.

Sample distribution.

We have constructed two sets of data. The first set of accounting variables includes those that were reported one year prior to the initiation of the procedure dealing with firms’ performance (EBITDA/TA and ROA), financial needs (LEV and WC/TA), level of capital (TA and Equities), and liquidity (CR and QR). The second set captures firms’ features, such as age (AGE), partnership legal form (Legal Form), and activity sector type (Industry, Trade, Transport, or Restaurant). Additionally, we also included the 2019 level of investment expenditures per capita at a regional level (Invest) as a proxy of local development. Detailed definitions of our variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables.

| Procedure | Variable equal to 0 if the firm was subject to an amicable liquidation, 1 to a judicial liquidation, 2 to a sauvegarde procedure and 3 to a redressement judiciaire procedure. |

| First Lockdown | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the bankruptcy procedure was triggered during the first lockdown of 2020 and 0 otherwise. |

| First Post-Lockdown | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the bankruptcy procedure was triggered between the first lockdown and the second lockdown of 2020 and 0 otherwise. |

| Second Lockdown | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the bankruptcy procedure was triggered during the second lockdown of 2020 and 0 otherwise. |

| Second Post-Lockdown | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the bankruptcy procedure was triggered after the second lockdown of 2020 and 0 otherwise. |

| EBITDA/TA | Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization as a percentage of total assets. |

| LEV | Ratio between the value of total debts and the value of total assets. |

| TA | Value of total assets. |

| CR | Ratio between current assets and current liabilities. |

| ROA | Ratio between the net income and the value of total assets. |

| WC/TA | Ratio between the working capital and the value of total assets. |

| Equity | Value of firm’s equity. |

| QR | Current assets less inventories divided by current liabilities. |

| Age | Age of firm measured in years. |

| Legal Form | Dummy variable that identifies partnership firms. |

| Industry | Dummy variable that identifies industrial firms. |

| Trade | Dummy variable that identifies firms operating in the trade sector. |

| Transport | Dummy variable that identifies transport firms. |

| Restaurant | Dummy variable that identifies firms with restaurant activities. |

| Invest | Investment expenditures per capita at regional level. |

Notes: Our financial variables were extracted from the DIANE database of Bureau van Dijk while Invest from the INSEE (French Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies).

Average and median values of our variables are presented in Table 2 for each subsample of firms facing amicable liquidation (column 1), judicial liquidation (column 2), the sauvegarde procedure (column 3), and the redressement judiciaire procedure (column 4). Several observations can be drawn from the summary statistics. First, firms that engaged in an out-of-court debt settlement were associated with a low operational or economic performance (EBITDA/TA and ROA) and a high degree of indebtedness (LEV). Additionally, firms that settled debts in court through judicial liquidation, on average, had the lowest equity value (Equity), implying less financial involvement from owners. Second, firms that were able to trigger a sauvegarde procedure were, on average, the largest firms in our sample (TA) and were also associated with high values of owners’ investment (Equity); however, firms subject to a redressement judiciaire procedure, on average, present low degrees of liquidity (CR and QR). The procedure of redressement judiciaire was designed for firms in payment default, which generally occurs when firms lack liquidity. Third, the subsample of out-of-court exits includes firms that have, on average, less experience (AGE), are primarily nonpartnership firms (Legal Form), and operate in the industry and trade sectors. Fourth, t-tests for differences in means between the subsamples suggest that the four subsamples statistically differ in terms of indebtedness degree (LEV), firm’s size (TA), and liquidity (CR and QR).

Table 2.

Summary statistics. Average and median values per subsample.

| Subsamples |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Amicable Liquidation (1.) | Judicial Liquidation (2.) | Sauvegarde (3.) | Redressement (4.) | 1. vs 2. t-test | 1. vs 3. t-test | 1. vs 4. t-test | 2. vs 3. t-test | 2. vs 4. t-test | 3. vs 4. t-test |

| A. Pandemic periods | ||||||||||

| First Lockdown | 0.043 (.) | 0.051 (.) | 0.058 (.) | 0.051 (.) | 0.358 | 0.329 | 0.517 | 0.646 | 0.985 | 0.680 |

| First Post-Lockdown | 0.202 (.) | 0.297 (.) | 0.214 (.) | 0.156 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.679 | 0.028 ** | 0.010 ** | 0.000 *** | 0.057 * |

| Second Lockdown | 0.070 (.) | 0.073 (.) | 0.147 (.) | 0.078 (.) | 0.758 | 0.000 *** | 0.572 | 0.000 *** | 0.727 | 0.004 *** |

| Second Post-Lockdown | 0.103 (.) | 0.150 (.) | 0.121 (.) | 0.114 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.433 | 0.522 | 0.242 | 0.047 ** | 0.792 |

| B. Accounting variables | ||||||||||

| EBITDA/TA | − 0.241 (0.070) | 0.044 (0.004) | − 0.021 (0.000) | − 0.104 (−0.017) | 0.052 * | 0.539 | 0.578 | 0.559 | 0.057 * | 0.005 *** |

| LEV | 9.445 (3.277) | 0.679 (0.218) | 0.941 (0.845) | 1.200 (0.958) | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.111 | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** |

| TA (K€) | 742.418 (273.4) | 3240.32 (740.4) | 9413.6 (1831.2) | 2895.14 (878.4) | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.582 | 0.000 *** |

| CR | 3.969 (1.624) | 1.413 (1.087) | 1.934 (1.123) | 1.118 (0.927) | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.012 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.000 *** |

| ROA | − 0.661 (0.019) | 0.108 (0.003) | − 0.091 (−0.017) | − 0.246 (−0.066) | 0.000 *** | 0.123 | 0.095 * | 0.080 * | 0.000 *** | 0.003 *** |

| WC/TA | 0.397 (0.108) | 0.077 (0.000) | − 0.011 (0.045) | − 0.220 (−0.080) | 0.148 | 0.467 | 0.110 | 0.289 | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** |

| Equity (K€) | 740.828 (166.1) | 358.214 (101.5) | 2770.84 (404.5) | 851.710 (208.9) | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.548 | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.005 *** |

| QR | 1.140 (0.947) | 3.669 (1.161) | 1.584 (0.879) | 0.860 (0.696) | 0.000 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** |

| C. Firm’s features | ||||||||||

| Age | 13.327 (9) | 15.990 (11) | 16.545 (11) | 16.589 (13) | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.597 | 0.429 | 0.970 |

| Legal Form | 0.329 (.) | 0.468 (.) | 0.531 (.) | 0.465 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.078 * | 0.911 | 0.104 |

| Industry | 0.228 (.) | 0.418 (.) | 0.246 (.) | 0.360 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.570 | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.025 ** | 0.003 *** |

| Trade | 0.359 (.) | 0.225 (.) | 0.295 (.) | 0.234 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.064 * | 0.000 *** | 0.021 ** | 0.682 | 0.084 * |

| Transport | 0.026 (.) | 0.074 (.) | 0.031 (.) | 0.046 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.652 | 0.030 ** | 0.017 ** | 0.034 ** | 0.352 |

| Restaurant | 0.118 (.) | 0.055 (.) | 0.094 (.) | 0.095 (.) | 0.000 *** | 0.279 | 0.157 | 0.022 ** | 0.002 *** | 0.967 |

| Invest (€) | 159.795 (156) | 160.054 (156) | 168.290 (156) | 170.459 (153) | 0.896 | 0.038 ** | 0.003 | 0.058 * | 0.004 *** | 0.779 |

| Number of firms: | 1271 | 1478 | 224 | 475 | ||||||

Notes: Average values of the variables are reported for each subsample of firms dealing with the amicable liquidation (column 1), the judicial liquidation (column 2), the sauvegarde procedure (column 3) and the redressement judiciaire procedure (column 4). Median values are included in the brackets. p-values of the t-tests for difference in means between the subsamples are reported in the last columns. * implies a difference in means that is significant at the 10% level, ** at the 5% level and *** at the 1% level.

4. Empirical analysis

4.1. Multinomial probit approach

According to Cheng and Long (2007), the most commonly used econometric model to examine discrete choice data is the multinomial logit model. However, this approach relies on the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA), assuming that the choice between two alternatives is not affected by the features of other available alternatives. The multinomial logit model is inappropriate when this assumption is violated (Powers and Xie, 2008). The Hausman and McFadden (1984) test and Small and Hsiao (1985) test confirm that the IIA assumption is rejected for our data set. Referencing Bowen and Wiersema (2004), the multinomial probit model (MPM) can be used in this case because it does not impose the IIA assumption, allowing the errors across different alternatives to be correlated. A similar solution was also applied by other studies, examining firms’ exit routes, such as Ponikvar et al. (2018) and Peljhan et al. (2020). As our main goal is to investigate how the enforcement of lockdowns relates to the likelihood of an institutional path, we use the following MPM:

| Prob (Procedurei = j) = Γ (α0 + α1 Pandemici + α2 Accountingi + α3 Featuresi + ξi) | (1) |

where i is the firm’s index and Γ is the multinomial probit function; Procedure is the dependent variable that equals 0 if the firm was subject to an amicable liquidation, 1 for a judicial liquidation, 2 for a sauvegarde procedure, and 3 for a redressement judiciaire procedure. Pandemic is a vector composed of First Lockdown, First Post-lockdown, Second Lockdown, and Second Post-lockdown; Accounting is the vector of accounting variables lagged one year prior to the opening of the procedure (EBITDA/TA, LEV, and a logarithm of TA and CR),8 whereas Features is the vector of additional explanatory variables (logarithm of Age, Legal Form, Industry, Trade, Transport, Restaurant, and a logarithm of Invest).9

One concern regarding our empirical framework is that a pre vs. post analysis does not account for inherent trends in outcomes.10 Our analysis would have benefited from a control group of firms not subject to lockdown or the pandemic crisis; however, as both lockdowns were enforced over the entire population of French firms, the assessment of our research question can only rely on a comparison with the pre-pandemic period. This is why we considered a large pre-pandemic subsample covering the period from January 1, 2019, to March 16, 2020. Additionally, Karlson et al. (2012) demonstrated that the size of the estimated coefficients depends on the other explanatory variables included in an econometric specification. In this sense, Wulff (2015) noted that a positive (negative) coefficient does not necessarily correspond to an increase (decrease) in the probability of a certain outcome, whereas the nonlinear relationship between an explanatory variable and that probability can even change sign of the coefficient. Consequently, Wulff (2015) argues that the interpretation of the results should rely on the marginal effects and predicted probabilities. Given that the sign of the coefficient cannot be used to assess the relationship between the dependent variable and pandemic periods, our interpretation will follow Wulff’s (2015) recommendations.

4.2. Estimates

An amicable liquidation or the sauvegarde procedure can be triggered by firms that are not in default of payment so that the creditors’ claims can be settled in full. According to Harada (2007), the probability of economic-forced exit is high for firms with loans from financial institutions and declining sales. Similarly, Balcaen et al. (2012) demonstrated that firms with less debt and high levels of cash tend to follow a voluntary exit more often than a court-driven exit. Consequently, we should expect firms holding more liquidity (CR) and previously operating with high levels of performance (EBITDA/TA) to have a higher likelihood of amicable liquidation or the sauvegarde procedure. Although a high level of debt (LEV) can be associated with more financial interests that can weaken reimbursement capacity, firms’ size can relate to the institutional path in two ways. More assets can imply higher stakeholder dependence, as captured in an extensive network of partners and creditors (Balcaen et al., 2011). Therefore, a voluntary liquidation decision can be complex and a firm’s negotiations with creditors can be long. A court-driven procedure (judicial liquidation, sauvegarde procedure, and redressement judiciaire procedure) can be triggered by firms because of the high costs required by the coordination of creditors (Bruche, 2011). In contrast, valuable assets can be easily converted into cash, allowing large firms to prevent credit default and embark on an amicable liquidation rather than on a court-driven procedure.

In Table 3, we present the marginal effects at the mean for our four procedures when the accounting variables and Age lag by one year (columns 1–4) and two years (columns 5–8).11 Our results suggest that the probability of a judicial liquidation (column 2) increased, on average, by 16.8% in the first post-lockdown period and by 12.8% in the second post-lockdown period, compared with the period prior to the first lockdown. These effect sizes are larger when we consider the two-year lag specification, ranging from 18.6% to 15%. Surprisingly, the probability of triggering a redressement judiciaire procedure after the first lockdown was, on average, 6.2% lower (column 4) than the probability of triggering a similar procedure prior to the pandemic crisis. The new environment that emerged, based on travel restrictions and social distancing, following the first lockdown harmed the capacity of defaulted firms to reorganize their activities in court. In contrast, non-defaulted firms had, on average, more chances to restructure their operations through a sauvegarde procedure during the second lockdown (columns 3 and 7). These firms likely took advantage of the lockdown context to negotiate with creditors and identify solutions with the court administrator to facilitate the firm’s adaptation to the new environment.

Table 3.

French bankruptcy procedures and pandemic periods.

| Lag = 1 year |

Lag = 2 years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Amicable Liquidation (1) | Judicial Liquidation (2) | Sauvegarde (3) | Redressement (4) | Amicable Liquidation (5) | Judicial Liquidation (6) | Sauvegarde (7) | Redressement (8) |

| First Lockdown | − 0.021 | 0.045 | − 0.003 | − 0.022 | − 0.067 | 0.083 * | 0.009 | − 0.025 |

| (0.046) | (0.042) | (0.014) | (0.020) | (0.045) | (0.046) | (0.019) | (0.026) | |

| First Post-Lockdown | − 0.093 | 0.168 *** | − 0.013 | − 0.062 *** | − 0.094 *** | 0.186 *** | − 0.015 | − 0.077 *** |

| (0.027) | (0.025) | (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.009) | (0.013) | |

| Second Lockdown | − 0.049 | 0.026 | 0.044 ** | − 0.020 | − 0.033 | 0.004 | 0.048 ** | − 0.018 |

| (0.039) | (0.035) | (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.041) | (0.040) | (0.020) | (0.022) | |

| Second Post-Lockdown | − 0.103 *** | 0.128 *** | − 0.001 | − 0.024 * | − 0.100 *** | 0.150 *** | − 0.007 | − 0.042 ** |

| (0.033) | (0.031) | (0.011) | (0.014) | (0.030) | (0.031) | (0.012) | (0.016) | |

| EBITDA/TA lag | 0.016 | − 0.002 | − 0.002 | − 0.012 * | 0.026 ** | − 0.009 | − 0.005 *** | − 0.012 *** |

| (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.002) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.001) | (0.003) | |

| LEV lag | 0.067 *** | − 0.055 *** | − 0.005 *** | − 0.007 ** | 0.049 *** | − 0.024 ** | − 0.008 *** | − 0.018 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Logarithm (TA lag) | − 0.292 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.084 *** | − 0.253 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.068 *** |

| (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.025) | (0.023) | (0.009) | (0.013) | |

| CR lag | 0.049 *** | − 0.012 | 0.002 | − 0.039 *** | 0.044 *** | − 0.029 *** | 0.001 | − 0.017 ** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.018) | (0.005) | (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| Logarithm (Age lag) | 0.084 *** | − 0.076 *** | − 0.017 ** | 0.009 | 0.044 * | − 0.027 | − 0.015 * | − 0.002 |

| (0.025) | (0.022) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.009) | (0.015) | |

| Legal Form | − 0.072 *** | 0.055 *** | 0.004 | 0.013 | − 0.093 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.010 | 0.022 |

| (0.021) | (0.019) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.009) | (0.014) | |

| Industry | − 0.107 *** | 0.131 *** | − 0.025 *** | 0.000 | − 0.111 *** | 0.144 *** | − 0.030 *** | − 0.004 |

| (0.028) | (0.025) | (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.009) | (0.017) | |

| Trade | 0.064 ** | − 0.044 * | − 0.002 | − 0.017 | 0.080 *** | − 0.047 * | − 0.006 | − 0.027 |

| (0.029) | (0.026) | (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.030) | (0.028) | (0.010) | (0.017) | |

| Transport | − 0.219 *** | 0.252 *** | − 0.022 * | − 0.011 | − 0.194 *** | 0.235 *** | − 0.027 ** | − 0.014 |

| (0.048) | (0.046) | (0.012) | (0.023) | (0.044) | (0.047) | (0.013) | (0.030) | |

| Restaurant | 0.082 ** | − 0.113 *** | 0.021 | 0.009 | 0.077 * | − 0.122 *** | 0.026 | 0.019 |

| (0.038) | (0.033) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.042) | (0.038) | (0.021) | (0.027) | |

| Logarithm (Invest) | − 0.027 | − 0.056 | 0.024 | 0.058 | − 0.133 | 0.032 | 0.027 | 0.074 |

| (0.092) | (0.082) | (0.035) | (0.049) | (0.114) | (0.108) | (0.041) | (0.063) | |

| Observations | 3488 | 2899 | ||||||

| Wald chi-square | 745.59 *** | 616.20 *** | ||||||

| Log pseudolikelihood | − 3121.4 | − 2912.4 | ||||||

| Maximum VIF | 1.57 | 1.58 | ||||||

| Prediction rate (%) | 66.03% | 59.68% | ||||||

Notes: Marginal effects at the mean were estimated using a multinomial probit regression with robust standard errors. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to 0 if the firm was subject to an amicable liquidation, 1 to a judicial liquidation, 2 to a sauvegarde procedure and 3 to a redressement judiciaire procedure. The prediction rate (%) represents the percentage of correctly predicted observations. Delta-method standard errors are included in the brackets. * implies a significant coefficient at the 10% level, ** at 5% level, and *** at the 1% level. Detailed definitions of the variables are presented in Table 1.

In terms of control variables, the likelihood of amicable liquidation was high for firms with high levels of debt (LEV) and liquidity (CR). Holding an asset value (logarithm (TA)) higher by 1% in the year previous to commencement of a bankruptcy procedure increased the probability of a court-driven procedure by 5.4% for judicial liquidation (column 2) and 3.6% for the sauvegarde procedure (column 3) and the redressement judiciaire procedure (column 4).12 The latter result suggests that large firms had a high likelihood of legally restructuring operations. Given that such firms must manage high stakeholder dependence (Balcaen et al., 2011), out-of-court negotiations with a large cohort of partners and creditors may fail. Additionally, on average, industrial and transport firms had a high likelihood of liquidating assets in court (columns 2 and 6) and a low likelihood of an out-of-court exit (columns 1 and 5). Table 3 also offers some insights regarding the consistency of our regressions. First, no severe multicollinearity was detected, as the maximum variance inflation factor is below 10. Second, the proportion of correctly predicted cases is higher than 65% only for the econometric specification based on the one-year lag. Third, the Wald test confirms that at least one coefficient is statistically different than zero.

We next graph the predicted probabilities of MPM by type of institutional path.13 This approach allows us to better understand the changes in these predicted probabilities following the two lockdowns. Fig. 3 shows the evolution of the monthly averages of predicted probabilities that were estimated in columns 1–4 of Table 3. The strongest evidence that confirms the previous findings primarily relates to the three court-driven procedures. In the case of judicial liquidation, the average predicted probability increased from 36.5% prior to the pandemic crisis to 55% during the first post-lockdown period and slightly lowered to 51.7% during the second post-lockdown period. This finding is also strengthened by the estimates in Appendix A that shows the coefficients using the multinomial probit approach by considering the group of firms subject to judicial liquidation as the comparison group. Additionally, the average likelihood of a sauvegarde procedure reached the highest value of 12% during the second lockdown. It is also notable that the largest drop in the likelihood of the redressement judiciaire procedure occurred during the period between the two lockdowns. This result was also confirmed in column 4 of Table 3.

Fig. 3.

Monthly averages of predicted probabilities. Estimates based on the first econometric specification.

4.3. Robustness check

Following Stef and Zenou (2021), we assess the robustness of our findings using an alternative set of accounting variables composed of ROA, WC/TA, the logarithm of Equity,14 and QR.15 Estimates are presented in Table 4. Surprisingly, the likelihood of an amicable liquidation decreased by 9.7% during the first lockdown, 13.7% after the first lockdown, 8.7% during the second lockdown, and 15.8% after the second lockdown (column 1). However, these marginal effects are estimated using only 71.3% of the initial sample. The other results regarding court-driven procedures are robust compared with the previous findings. Table 4 shows that the effect sizes are large for First Post-lockdown and Second Post-lockdown, mainly in the case of judicial liquidation. An average increase in the likelihood of court-driven exits, ranging from 14.7% to 19%, should have been expected in the post-quarantine periods.

Table 4.

French bankruptcy procedures and pandemic periods. Alternative accounting variables.

| Lag = 1 year |

Lag = 2 years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Amicable Liquidation (1) | Judicial Liquidation (2) | Sauvegarde (3) | Redressement (4) | Amicable Liquidation (5) | Judicial Liquidation (6) | Sauvegarde (7) | Redressement (8) |

| First Lockdown | − 0.097 ** | 0.080 * | 0.010 | 0.006 | − 0.078 * | 0.045 | 0.046 | − 0.013 |

| (0.042) | (0.048) | (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.043) | (0.051) | (0.030) | (0.032) | |

| First Post-Lockdown | − 0.137 *** | 0.190 *** | − 0.022 ** | − 0.030 *** | − 0.111 *** | 0.178 *** | − 0.013 | − 0.054 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.024) | (0.028) | (0.012) | (0.016) | |

| Second Lockdown | − 0.087 ** | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.009 | − 0.052 | − 0.011 | 0.059 ** | 0.003 |

| (0.037) | (0.044) | (0.023) | (0.018) | (0.037) | (0.044) | (0.027) | (0.028) | |

| Second Post-Lockdown | − 0.158 *** | 0.147 *** | 0.009 | 0.002 | − 0.124 *** | 0.161 *** | − 0.010 | − 0.027 |

| (0.027) | (0.032) | (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.029) | (0.033) | (0.015) | (0.021) | |

| ROA lag | 0.001 | 0.004 | − 0.003 * | − 0.002 | 0.031 *** | − 0.008 | − 0.008 ** | − 0.015 ** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.003) | (0.010) | |

| WC/TA lag | 0.010 *** | − 0.006 * | − 0.002 *** | − 0.001 ** | 0.023 *** | − 0.010 * | − 0.006 *** | − 0.008 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Logarithm (Equity lag) | 0.132 *** | − 0.233 *** | 0.062 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.111 *** | − 0.238 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.064 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.016) | (0.019) | (0.008) | (0.011) | |

| QR lag | − 0.031 ** | 0.053 *** | 0.003 | − 0.025 *** | − 0.058 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.005 | − 0.014 |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.004) | (0.015) | |

| Logarithm (Age lag) | − 0.119 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.017 | 0.019 ** | − 0.095 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.009 | 0.019 |

| (0.023) | (0.024) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.024) | (0.026) | (0.012) | (0.016) | |

| Legal Form | − 0.156 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.024 ** | 0.019 ** | − 0.153 *** | 0.100 *** | 0.022 ** | 0.031 ** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.010) | (0.015) | |

| Industry | − 0.198 *** | 0.208 *** | − 0.024 ** | 0.013 | − 0.183 *** | 0.194 *** | − 0.031 *** | 0.020 |

| (0.025) | (0.027) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.025) | (0.029) | (0.012) | (0.019) | |

| Trade | 0.035 | − 0.023 | − 0.011 | − 0.002 | 0.038 | − 0.009 | − 0.012 | − 0.017 |

| (0.028) | (0.030) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.029) | (0.032) | (0.013) | (0.020) | |

| Transport | − 0.244 *** | 0.303 *** | − 0.039 *** | − 0.021 | − 0.208 *** | 0.304 *** | − 0.051 *** | − 0.046 |

| (0.034) | (0.040) | (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.035) | (0.045) | (0.011) | (0.031) | |

| Restaurant | 0.134 *** | − 0.149 *** | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.136 *** | − 0.121 ** | − 0.006 | − 0.010 |

| (0.044) | (0.044) | (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.049) | (0.014) | (0.023) | (0.033) | |

| Logarithm (Invest) | 0.076 | − 0.124 | 0.034 | 0.014 | − 0.044 | 0.011 | − 0.021 | 0.053 |

| (0.091) | (0.101) | (0.053) | (0.048) | (0.092) | (0.102) | (0.057) | (0.077) | |

| Observations | 2487 | 2237 | ||||||

| Wald chi-square | 513.25 *** | 490.83 *** | ||||||

| Log pseudolikelihood | − 2396.2 | − 2295.0 | ||||||

| Maximum VIF | 1.60 | 1.60 | ||||||

| Prediction rate (%) | 60.07% | 57.58% | ||||||

Notes: Marginal effects at the mean were estimated using a multinomial probit regression with robust standard errors. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to 0 if the firm was subject to an amicable liquidation, 1 to a judicial liquidation, 2 to a sauvegarde procedure and 3 to a redressement judiciaire procedure. The prediction rate (%) represents the percentage of correctly predicted observations. Delta-method standard errors are included in the brackets. * implies a significant coefficient at the 10% level, ** at 5% level, and *** at the 1% level. Detailed definitions of the variables are presented in Table 1.

Moreover, firms with a high level of equity were associated with a high probability of voluntary liquidation (columns 1 and 5) or reorganization (columns 3, 4, 7, and 8). Similar findings are also presented in Appendix B, which considers the estimated coefficients of this robustness check. Owners can benefit from the residual value of assets if one of the voluntary liquidation or reorganization procedures is triggered. According to Carletti et al. (2020), the pandemic crisis not only drained the level of liquidity but also eroded the equity capital of firms severely impacted by the lockdown enforcement and reported high leverage and a small size prior to the crisis. Large investments encouraged owners to settle all firms’ claims outside of court or to restructure business activities. Interestingly, the marginal effects of QR seem to provide an opposite sign for the two liquidation procedures compared with the marginal effects of CR from Table 3. The major difference between the two liquidity ratios is that QR includes only current assets that can be converted into cash in less than three months. When the value of a firm’s inventory is excluded from the liquidity measure, the likelihood of judicial liquidation is subject to an average increase of 5.3%, while the likelihood of amicable liquidation is subject to an average decrease of 3.1%, following a 1% increase in QR. Hence, the value of firms’ inventory can have a significant influence in the arbitration between the two liquidation procedures.

We complete the robustness test with a graphical analysis based on the monthly averages of the predicted probabilities from columns 1–4 of Table 4. Fig. 4 reveals opposing patterns for amicable and judicial liquidation. The average likelihood of amicable liquidation progressively decreased from 43.9% (before the first lockdown) to 29.7% (after the second lockdown), whereas the average likelihood of judicial liquidation increased to 56.3%, mainly during the first post-lockdown period. On a different note, the likelihood of firms’ restructuring severely decreased during the period between the two lockdowns, during which the average likelihood of a sauvegarde procedure was 4.5% and that of a redressement judiciaire procedure was 6.6%.

Fig. 4.

Monthly averages of predicted probabilities. Estimates based on the second econometric specification.

5. Concluding remarks

This study investigates how the lockdown enforcement by French authorities is associated with the resolution of corporate insolvency. In this sense, we make a distinction between four legal procedures, namely the amicable liquidation (out-of-court exit), the judicial liquidation (court-driven exit), the restructuring procedure of sauvegarde available to non-defaulted firms, and the restructuring procedure of redressement judiciaire available to defaulted firms. Using a sample of 3488 non-listed French firms, our estimates yield three major findings. First, the likelihood of judicial liquidation increased after the lifting of the quarantines compared to the pre-pandemic period. Second, the non-defaulted firms had a higher likelihood to reorganize in court during the second lockdown. Third, the lifting of the first lockdown led to a decrease in the probability of restructuring the assets of defaulted firms.

Although the main objective of the lockdown was to limit the spread of the virus, its enforcement has not provided strong incentives to exit through an out-of-court procedure such as the amicable liquidation. As a matter of fact, our estimates report an expected average increase in the likelihood of court-driven exit ranging from 12.8% to 19% points during the post-lockdown periods. Bernstein et al. (2019) argued that a firm’s liquidation driven by the court can lead to an inefficient allocation of assets in the presence of local market frictions. Considering that the pandemic produced liquidity shortcomings, finding a potential user for firms’ assets may require high search costs that can increase the bankruptcy costs and limit the creditors’ debt recovery. Therefore, the use of the amicable liquidation should be encouraged during and after the pandemic crisis because it can accelerate the allocation of assets to more successful entrepreneurs. Moreover, longer bankruptcy delays can prevent financially distressed firms from exiting and, also, the formation of new firms (Melcarne and Ramello, 2020). Hence, the pressure on the insolvency courts may be diminished through the promotion of the out-of-court exit.

Nevertheless, the judicial liquidation can represent a solution to the exit of firms severely affected by the COVID-19 crisis, called “zombie” companies. Demary (2021) employed the concept of “zombification” to describe firms that survive without having the pressure to restructure their activities to stay in the market. Such “zombification” can be supported by government’s rescues measures or even debt deleveraging that can disempower the managers and reduce their incentives to maintain the firm’s competitiveness. Not surprisingly, the COVID-19 crisis led to an average 37% drop in judicial liquidations on French territory in 2020 compared to 2019 due to the massive support from the State to private companies through a system of financial aid (solidarity fund and loan guaranteed by the State). If the creditors’ right to trigger the debtor’s liquidation is restricted, one may expect more “zombification” among firms facing financial difficulties. Philippon (2021) pointed out that a laissez-faire public approach can lead to excessive liquidation while the efficient reallocation of assets can be hampered by an indiscriminate bailout of firms. Hence, public measures aimed to restore the financial health of firms affected by the pandemic must limit the incentives of non-viable firms to continue their operations.

Based on our findings, firms in default of payment had difficulty engaging in restructuring, mainly during the first post-lockdown period. However, court-driven reorganization procedures can offer useful mechanisms to preserve the value of assets, particularly during a pandemic. According to James (2016), firms can strategically file for a restructuring procedure not only to preserve more asset value for business stakeholders but also to stem the decline in performance through measures aimed at overcoming others’ competitive advantages. Conflicts of interests between creditors and other stakeholders can be mitigated by preserving the firm’s value. Using a legal index based on a scale from 0% (no protection) to 100% (high level of protection), Blazy et al. (2018) revealed that the redressement judiciaire procedure can provide a high degree of asset protection (82%), close to the protection provided by judicial liquidation (91%). Additionally, restructuring seems to be less costly for shareholders and creditors. If the commercial courts can diminish the risk of filtering failure, this could lead to increased restructuring of nonviable firms and liquidation of viable firms (Fisher and Martel, 2004, Laitinen, 2011, Stef, 2017). The use of a court-driven reorganization should be encouraged during and after the pandemic crisis, as it can allow preservation of both asset value and employment.

However, it should be noted that our findings are based on short-term results that considered only the two French lockdowns that were enforced in 2020. A long-term empirical approach that integrates additional observation years and other potential lockdown periods would be suitable to comprehensively investigate the relationship between the pandemic crisis and firms’ failure. An analysis regarding insolvency resolution during the pandemic periods can also be further expanded to different legal systems, such as the common law system, which is mainly recognized for its creditor-friendly orientation that opposes the debtor-friendly orientation associated with the civil law systems. Understanding the consequences of the arbitration between the protection of creditors’ interest and employment preservation (firm survival) is of major importance for legislators seeking to accelerate the recovery of the national economy in the post-pandemic context.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nicolae Stef: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Visualization Jean-Joachim Bissieux: Conceptualization, Resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Regional Council (Project COVID-ENT). We are also grateful to Antoine Jolly and two anonymous referees for their insightful comments.

Footnotes

The legal framework of bankruptcy procedures is covered by book No. 6 of the French commercial code.

The French law also proposes two procedures to negotiate the debt in a confidential and amicable manner under the guidance of a trustee appointed by the Commercial Court, i.e., the conciliation procedure and mandat ad hoc procedure.

We identified these public measures from press releases provided by the French Ministry of Finance Economics and Revival.

According to the order number 2020–341 of March 27, 2020, these provisions remained in force until August 24, 2020. A more detailed analysis of this governmental order is provided by Lemercier and Mercier (2020).

We have manually identified the firms that triggered a sauvegarde procedure or redressement judiciaire procedure using www.societe.com and www.procedurecollective.fr based on the French Official Bulletin of Civil and Commercial Announcements. The bulletin is a public journal of legal announcements of all the acts registered in the Trade and Companies Register of France.

Data on the annual number of amicable liquidations are not available for France.

The first lockdown covers the period from March 17, 2020, to May 5, 2020, whereas the second lockdown was the period from October 30, 2020, to December 14, 2020.

The vector of accounting variables relies on variables that were found to have an explanatory power for firms’ exit paths, such as voluntary dissolution or involuntary liquidation (Irfan et al., 2018, Jabeur and Fahmi, 2018, Ponikvar et al., 2018, Stef and Zenou, 2021).

The multinomial logit approach provides similar results to the multinomial probit model (results available upon request).

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for pointing out this issue.

We used the command margins in STATA 14.2 to compute the marginal effects. In the case of dummy variables, margins calculate the discrete first difference from the base category.

Effect sizes were calculated by multiplying the coefficients with the base 10 logarithm of 1.01.

For a given firm, MPM predicts a probability for each of the four institutional paths. The sum of the four predicted probabilities is equal to 1.

We treated the negative values of Equity as equal to 0 in the log-transformed function.

Table 7 in Appendix C reports an additional robustness test by including regional effects in the econometric specification of Eq. (1). The previous findings remain robust.

Appendix A.

See Table 5.

Table 5.

Multinomial probit approach. French bankruptcy procedures and pandemic periods.

| Lag = 1 year | Lag = 2 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Amicable Liquidation (1) | Sauvegarde (2) | Redressement (3) | Amicable Liquidation (4) | Sauvegarde (5) | Redressement (6) |

| First Lockdown | − 0.133 | − 0.129 | − 0.244 | − 0.302 * | − 0.061 | − 0.287 |

| (0.163) | (0.205) | (0.184) | (0.176) | (0.211) | (0.194) | |

| First Post-Lockdown | − 0.515 *** | − 0.520 *** | − 0.798 *** | − 0.553 *** | − 0.524 *** | − 0.790 *** |

| (0.094) | (0.124) | (0.103) | (0.095) | (0.132) | (0.108) | |

| Second Lockdown | − 0.146 | 0.346 ** | − 0.188 | − 0.080 | 0.389 ** | − 0.096 |

| (0.137) | (0.161) | (0.153) | (0.158) | (0.170) | (0.159) | |

| Second Post-Lockdown | − 0.453 *** | − 0.278 * | − 0.419 *** | − 0.499 *** | − 0.360 ** | − 0.509 *** |

| (0.120) | (0.156) | (0.124) | (0.119) | (0.162) | (0.128) | |

| EBITDA/TA lag | 0.032 | − 0.020 | − 0.074 | 0.071 | − 0.039 | − 0.043 |

| (0.040) | (0.032) | (0.054) | (0.045) | (0.033) | (0.034) | |

| LEV lag | 0.241 *** | 0.057 | 0.075 * | 0.150 *** | − 0.037 | − 0.045 |

| (0.061) | (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.037) | (0.031) | (0.030) | |

| Logarithm (TA lag) | − 0.799 *** | 0.744 *** | 0.265 *** | − 0.746 *** | 0.563 *** | 0.121 |

| (0.101) | (0.088) | (0.076) | (0.095) | (0.103) | (0.078) | |

| CR lag | 0.113 *** | 0.041 | − 0.216 *** | 0.151 *** | 0.070 | − 0.028 |

| (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.051) | (0.041) | (0.044) | (0.050) | |

| Logarithm (Age lag) | 0.317 *** | − 0.038 | 0.223 ** | 0.145 | − 0.113 | 0.042 |

| (0.089) | (0.114) | (0.093) | (0.095) | (0.116) | (0.098) | |

| Legal Form | − 0.250 *** | − 0.075 | − 0.036 | − 0.317 *** | − 0.014 | − 0.012 |

| (0.077) | (0.100) | (0.082) | (0.082) | (0.103) | (0.087) | |

| Industry | − 0.472 *** | − 0.601 *** | − 0.276 *** | − 0.516 *** | − 0.625 *** | − 0.301 *** |

| (0.103) | (0.125) | (0.103) | (0.106) | (0.131) | (0.109) | |

| Trade | 0.211 ** | 0.066 | − 0.014 | 0.256 ** | 0.022 | − 0.042 |

| (0.105) | (0.130) | (0.113) | (0.109) | (0.136) | (0.118) | |

| Transport | − 0.933 *** | − 0.800 *** | − 0.544 *** | − 0.905 *** | − 0.794 *** | − 0.483 ** |

| (0.192) | (0.248) | (0.188) | (0.204) | (0.268) | (0.205) | |

| Restaurant | 0.418 *** | 0.501 *** | 0.336 ** | 0.417 *** | 0.508 ** | 0.355 ** |

| (0.140) | (0.191) | (0.160) | (0.157) | (0.205) | (0.175) | |

| Logarithm (Invest) | 0.074 | 0.417 | 0.492 | − 0.341 | 0.230 | 0.302 |

| (0.325) | (0.479) | (0.376) | (0.425) | (0.515) | (0.413) | |

| Intercept | 1.161 | − 4.281 *** | − 2.364 *** | 2.380 ** | − 3.088 *** | − 1.321 |

| (0.777) | (1.100) | (0.859) | (0.942) | (1.192) | (0.929) | |

| Observations | 3488 | 2899 | ||||

| Wald chi-square | 745.59 *** | 616.20 *** | ||||

| Log pseudolikelihood | − 3121.4 | − 2912.4 | ||||

| Maximum VIF | 1.57 | 1.58 | ||||

| Prediction rate (%) | 66.03% | 59.68% | ||||

Notes: Coefficients were estimated using a multinomial probit regression with robust standard errors. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to 0 if the firm was subject to an amicable liquidation, 1 to a judicial liquidation, 2 to a sauvegarde procedure and 3 to a redressement judiciaire procedure. The group of firms that were subject to a judicial liquidation is the comparison group. The prediction rate (%) represents the percentage of correctly predicted observations. Delta-method standard errors are included in the brackets. * implies a significant coefficient at the 10% level, ** at 5% level, and *** at the 1% level. Detailed definitions of the variables are presented in Table 1.

Appendix B

See Table 6.

Table 6.

Multinomial probit approach. Alternative accounting variables.

| Lag = 1 year | Lag = 2 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Amicable Liquidation (1) | Sauvegarde (2) | Redressement (3) | Amicable Liquidation (4) | Sauvegarde (5) | Redressement (6) |

| First Lockdown | − 0.367 ** | − 0.038 | − 0.077 | − 0.281 | 0.267 | − 0.143 |

| (0.179) | (0.230) | (0.230) | (0.190) | (0.233) | (0.221) | |

| First Post-Lockdown | − 0.642 *** | − 0.578 *** | − 0.632 *** | − 0.590 *** | − 0.452 *** | − 0.604 *** |

| (0.098) | (0.149) | (0.130) | (0.106) | (0.153) | (0.125) | |

| Second Lockdown | − 0.276 * | 0.240 | 0.010 | − 0.106 | 0.453 ** | 0.044 |

| (0.153) | (0.194) | (0.183) | (0.163) | (0.199) | (0.181) | |

| Second Post-Lockdown | − 0.640 *** | − 0.151 | − 0.223 | − 0.604 *** | − 0.381 ** | − 0.419 *** |

| (0.123) | (0.171) | (0.148) | (0.130) | (0.191) | (0.148) | |

| ROA lag | − 0.006 | − 0.042 * | − 0.026 | 0.087 ** | − 0.063 | − 0.062 |

| (0.023) | (0.022) | (0.019) | (0.042) | (0.041) | (0.038) | |

| WC/TA lag | 0.032 ** | − 0.013 * | − 0.001 | 0.073 *** | − 0.034 ** | − 0.019 |

| (0.014) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.024) | (0.014) | (0.013) | |

| Logarithm (Equity lag) | 0.693 *** | 1.043 *** | 0.776 *** | 0.696 *** | 1.052 *** | 0.755 *** |

| (0.066) | (0.095) | (0.076) | (0.067) | (0.105) | (0.074) | |

| QR lag | − 0.159 *** | − 0.069 ** | − 0.323 *** | − 0.260 *** | − 0.077 ** | − 0.194 *** |

| (0.047) | (0.030) | (0.064) | (0.031) | (0.039) | (0.060) | |

| Logarithm (Age lag) | − 0.402 *** | 0.030 | 0.039 | − 0.350 *** | − 0.041 | − 0.033 |

| (0.089) | (0.124) | (0.109) | (0.096) | (0.135) | (0.108) | |

| Legal Form | − 0.547 *** | 0.040 | − 0.023 | − 0.554 *** | 0.024 | − 0.026 |

| (0.081) | (0.110) | (0.099) | (0.088) | (0.114) | (0.097) | |

| Industry | − 0.820 *** | − 0.616 *** | − 0.235 * | − 0.809 *** | − 0.667 *** | − 0.252 ** |

| (0.105) | (0.145) | (0.131) | (0.111) | (0.149) | (0.125) | |

| Trade | 0.116 | − 0.075 | 0.019 | 0.104 | − 0.107 | − 0.072 |

| (0.109) | (0.151) | (0.140) | (0.115) | (0.155) | (0.136) | |

| Transport | − 1.218 *** | − 1.082 *** | − 0.711 ** | − 1.156 *** | − 1.347 *** | − 0.759 *** |

| (0.207) | (0.329) | (0.281) | (0.212) | (0.346) | (0.257) | |

| Restaurant | 0.548 *** | 0.332 | 0.375 * | 0.526 *** | 0.183 | 0.192 |

| (0.165) | (0.246) | (0.216) | (0.184) | (0.275) | (0.228) | |

| Logarithm (Invest) | 0.382 | 0.564 | 0.355 | − 0.120 | − 0.220 | 0.238 |

| (0.350) | (0.633) | (0.522) | (0.356) | (0.630) | (0.484) | |

| Intercept | − 1.035 | − 4.468 *** | − 2.830 ** | 0.072 | − 2.612 * | − 2.300 ** |

| (0.771) | (1.413) | (1.162) | (0.790) | (1.426) | (1.066) | |

| Observations | 2487 | 2237 | ||||

| Wald chi-square | 513.25 *** | 490.83 *** | ||||

| Log pseudolikelihood | − 2396.2 | − 2295.0 | ||||

| Maximum VIF | 1.60 | 1.60 | ||||

| Prediction rate (%) | 60.07% | 57.58% | ||||

Notes: Coefficients were estimated using a multinomial probit regression with robust standard errors. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to 0 if the firm was subject to an amicable liquidation, 1 to a judicial liquidation, 2 to a sauvegarde procedure and 3 to a redressement judiciaire procedure. The group of firms that were subject to a judicial liquidation is the comparison group. The prediction rate (%) represents the percentage of correctly predicted observations. Delta-method standard errors are included in the brackets. * implies a significant coefficient at the 10% level, ** at 5% level, and *** at the 1% level. Detailed definitions of the variables are presented in Table 1.

Appendix C

See Table 7.

Table 7.

French bankruptcy procedures and pandemic periods. Regional effects.

| Lag = 1 year |

Lag = 2 years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Amicable Liquidation (1) | Judicial Liquidation (2) | Sauvegarde (3) | Redressement (4) | Amicable Liquidation (5) | Judicial Liquidation (6) | Sauvegarde (7) | Redressement (8) |

| First Lockdown | − 0.022 | 0.046 | − 0.000 | − 0.023 | − 0.068 | 0.087 * | 0.011 | − 0.031 |

| (0.046) | (0.042) | (0.015) | (0.020) | (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.019) | (0.025) | |

| First Post-Lockdown | − 0.091 | 0.163 *** | − 0.011 | − 0.060 *** | − 0.093 *** | 0.182 *** | − 0.013 | − 0.075 *** |

| (0.027) | (0.025) | (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.009) | (0.013) | |

| Second Lockdown | − 0.054 | 0.023 | 0.048 ** | − 0.016 | − 0.037 | − 0.005 | 0.053 *** | − 0.010 |

| (0.039) | (0.035) | (0.019) | (0.018) | (0.041) | (0.040) | (0.013) | (0.023) | |

| Second Post-Lockdown | − 0.102 *** | 0.124 *** | − 0.001 | − 0.022 | − 0.099 *** | 0.145 *** | − 0.006 | − 0.040 ** |

| (0.033) | (0.031) | (0.011) | (0.014) | (0.030) | (0.031) | (0.012) | (0.017) | |

| EBITDA/TA lag | 0.016 | − 0.002 | − 0.002 | − 0.012 * | 0.027 *** | − 0.010 | − 0.005 *** | − 0.012 *** |

| (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.002) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.001) | (0.003) | |

| LEV lag | 0.067 *** | − 0.056 *** | − 0.005 *** | − 0.007 ** | 0.049 *** | − 0.025 *** | − 0.007 *** | − 0.018 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Logarithm (TA lag) | − 0.296 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.085 *** | − 0.255 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.070 *** |

| (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.023) | (0.009) | (0.013) | |

| CR lag | 0.048 *** | − 0.012 | 0.002 | − 0.037 *** | 0.045 *** | − 0.029 ** | 0.001 | − 0.017 ** |

| (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.002) | (0.006) | (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| Logarithm (Age lag) | 0.081 *** | − 0.077 *** | − 0.016 * | 0.012 | 0.039 | − 0.027 | − 0.014 | 0.002 |

| (0.025) | (0.022) | (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.025) | (0.009) | (0.015) | |

| Legal Form | − 0.074 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.005 | 0.016 | − 0.095 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.012 | 0.024 * |

| (0.022) | (0.020) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.008) | (0.014) | |

| Industry | − 0.107 *** | 0.141 *** | − 0.028 *** | − 0.005 | − 0.109 *** | 0.154 *** | − 0.035 *** | − 0.011 |

| (0.028) | (0.025) | (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.009) | (0.016) | |

| Trade | 0.063 ** | − 0.037 | − 0.004 | − 0.021 | 0.083 *** | − 0.041 | − 0.009 | − 0.033 ** |

| (0.029) | (0.027) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.010) | (0.017) | |