Abstract

Background: This study brings a human-centered design (HCD) perspective to understanding the patient experience when using noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with the goal of creating better strategies to improve NIV comfort and tolerance.

Methods: Using an HCD motivational approach, we created a semi-structured interview to uncover the patients’ journey while being treated with NIV. We interviewed 16 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) treated with NIV while hospitalized. Patients’ experiences were captured in a stepwise narrative creating a journey map as a framework describing the overall experience and highlighting the key processes, tensions, and flows. We broke the journey into phases, steps, emotions, and themes to get a clear picture of the overall experience levers for patients.

Results: The following themes promoted NIV tolerance: trust in the providers, the favorable impression of the facility and staff, understanding why the mask was needed, how NIV works and how long it will be needed, immediate relief of the threatening suffocating sensation, familiarity with similar treatments, use of meditation and mindfulness, and the realization that treatment was useful. The following themes deterred NIV tolerance: physical and psychological discomfort with the mask, impaired control, feeling of loss of control, and being misinformed.

Conclusions: Understanding the reality of patients with COPD treated with NIV will help refine strategies that can improve their experience and tolerance with NIV. Future research should test ideas with the best potential and generate prototypes and design iterations to be tested with patients.

Keywords: copd, noninvasive ventilation, patient experience, human-centered design, qualitative analysis

Background

This article contains supplemental material.

Among the 720,000 patients hospitalized yearly in the United States with a COPD exacerbation, more than 7% are treated with noninvasive ventilation (NIV).1,2 NIV refers to the delivery of ventilatory support to the lungs through a mask, which unloads respiratory muscles and improves alveolar recruitment. 3 In patients with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, such as severe COPD exacerbation, NIV significantly reduces the risk of endotracheal intubation and mortality.4-6 Although NIV is life-saving, NIV failure (intubation after an NIV trial) is associated with high mortality.7,8 Factors contributing to NIV failure include conditions related to the disease (e.g., inability to correct hypoxemia or hypercapnia), inappropriate settings, lack of knowledge of the staff, or patient intolerance leading to premature discontinuation.5,9,10 Several studies have reported that 10%-15% of patients receiving NIV develop intolerance, accounting for 9%-15% of all intubations.11-14 Due to poor tolerance, NIV is used on average for only 8 hours/day. Current strategies to improve patient tolerance concentrate on adjusting the settings on the ventilator or changing the interface and using anxiolytics.

While it is established that patients' cooperation and tolerance are essential to NIV success, patients’ perceptions and experiences with NIV are not well studied. Prior studies reported that patients express anxiety, fear, claustrophobia, and feelings of lacking control.15-17 However, most prior studies were performed outside the United States (different roles of clinical staff) or in non-COPD patients.

This study brings a human-centered design (HCD) perspective to understanding the patient experience when using NIV (emotions, experience, thinking) with the goal of creating better strategies to improve NIV comfort and tolerance. HCD is a methodology for analyzing problems from the perspective of people affected by them and uses their perspective to develop innovative solutions.18-20 This in turn helps bridge the gap(s) between research and practice with an evidence-based approach.21-23

Methods

Setting and Design

This study was conducted from June 19, 2020, to November 13, 2020, at a large, urban teaching hospital in Western Massachusetts that cares for more than 700 patients with COPD yearly. The study was approved by the Baystate Institutional Review Board.

Patient Selection

Each morning, the research assistant reviewed medical records to identify patients admitted for a COPD exacerbation, English speaking, treated with NIV for at least 3 hours, and able to consent. We purposely sampled adults from a mix of ages and genders, those with and without obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), those who did or did not use NIV before this admission, and those who have or have not been intubated. The interviews were performed in-person or by phone during hospitalization or after discharge. Patients received a $50 gift card at the end of the interview in appreciation for their time.

Interviews

Using the HCD motivational approach, we created a semi-structured interview guide to uncover the patient’s journey while being treated with NIV.24 We let the patients lead the conversation as much as possible and asked them to tell the story of their experience. We followed interesting tangents by eliciting anecdotes along the way, probing to understand emotions, motivations, and choices from their perspective. Patients told us the high and low parts of their experience. We probed to hear what they were thinking, feeling, doing, and saying at each step in their journey. The interview covered questions about: how the patient arrived at the hospital; their experience with NIV initiation; what treatment felt like physically, psychologically, and emotionally; what they understood about the treatment; how their clinical team supported them through the treatment; how it felt to have the NIV mask removed; thoughts and feelings about NIV after treatment; recommendations for future patients who will be treated with NIV; and recommendations for making the treatment experience more tolerable. (Supplement E1 in the online supplement (257.8KB, pdf) ) Interviews were conducted until we achieved heterogeneity of the sample and thematic saturation.

The interviews were conducted by the research assistant (TC), physician principal investigator (MS), and the collaborator (JM), all females. TC has a bachelor’s degree, MS has an MD and PhD, and JM has an MBA; all have experience with qualitative interviews. Interviewers were not a member of any patient’s clinical care team.

Transcription and Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The coding team consisted of MSS, TAC, JLM, CMS, and CEA. The initial codebook was created based on a review of the literature related to patient experience with NIV and informed by our interview guide. As we reviewed the transcripts and continued to interview patients, we modified the codebook to include emergent codes. MSS and TAC coded all the interview transcripts, with the first 4 interviews coded independently by MSS and TAC to check for agreement and code definition. Subsequently, TAC coded each transcript independently, and MSS or JLM reviewed the coded transcripts to ensure agreement and accuracy. The codebook was refined through regular research team meetings. The codebook went through changes until the research team agreed on codes and their definitions. Coding disagreements were discussed and resolved in team meetings.

In HCD methodology, in-context, empathetic interviews are aimed to surface hidden challenges and mental models that underly a problem.25,26 By probing deeper into the emotional experience, the researcher seeks to understand the patient's relationship with the systems, people, and technology they interact with. The logical steps of the patients’ experience are captured in a stepwise narrative creating a journey map as a framework describing the overall experience and highlighting the key processes, tensions, and flows. We broke the journey into phases, steps, emotions, and themes to get a clear picture of the overall experience levers for patients. First, we recognized the phases of the journey, which are the big picture stages that all patients experience. We coded the interviews by phases and then subcategorized each phase into steps, which are discrete aspects of the experience described by the patient. Each patient's description of a step was analyzed for emotions. We then coded each emotion as negative, neutral, or positive, and we tallied the number of negative, neutral, and positive emotions for each step. We calculated a sentiment score for each step as a percentage of negative, neutral, and positive emotion. Finally, we reviewed each phase and step and discussed themes that were emerging by phase. Themes were then divided into 2 categories, “themes that promote NIV tolerance” and “themes that deter NIV tolerance” for each phase. Verbatim quotes were first checked for context within the overall patient’s experience and attributed to themes. The presence of in-context quotes by multiple patients supported the identification of the theme. (A more detailed description of the Journey map creation can be found in Supplement E1 in the online supplement (257.8KB, pdf) .)

Results

We interviewed 16 patients: 9 in-person while hospitalized, 3 by phone while hospitalized, and 4 by phone after discharge. Eight were female, the median age was 67 (range 57 to 80), and 12 were oxygen dependent at home. Four patients had OSA and used continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP), 9 patients used NIV for the first time during this hospitalization, 3 were intubated during a past hospitalization, and 2 were intubated during the current hospitalization.

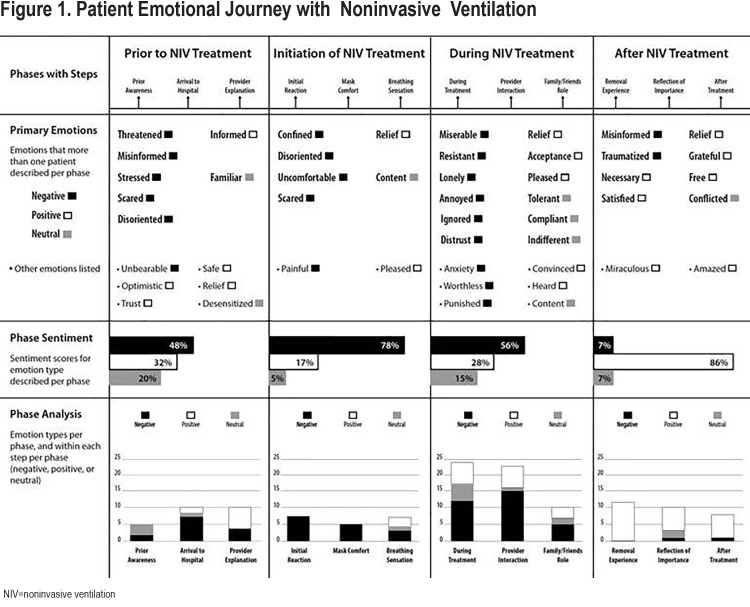

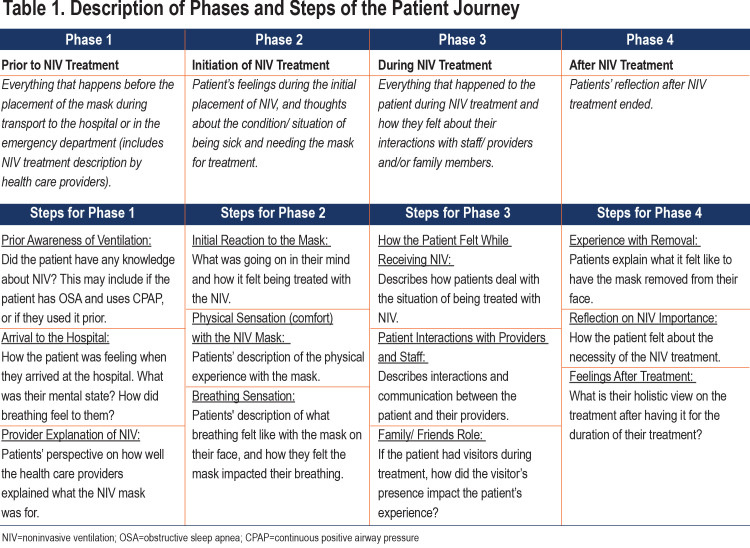

The journey map of the patient’s emotional experience with NIV is shown in Figure 1. The following phases were identified: (1) prior to NIV treatment (arrival to the emergency department, and the experience before the NIV mask application); (2) initiation of NIV treatment (preparation for starting NIV and NIV mask is placed on the patient’s face); (3) during NIV treatment (the patient is using NIV, continuously or intermittently); and (4) after NIV treatment (NIV discontinued) (Table 1). Below, we describe each phase with its steps and themes. One theme, periods of unconsciousness/ unawareness, was present in several phases; we did not consolidate it in 1 theme because identifying the theme as part of the phase could be helpful for process improvement. The emotions for each phase are depicted in Figure 1. The representative quotes for each theme are included in Table 2.

Phase 1: Prior to NIV Treatment Phase

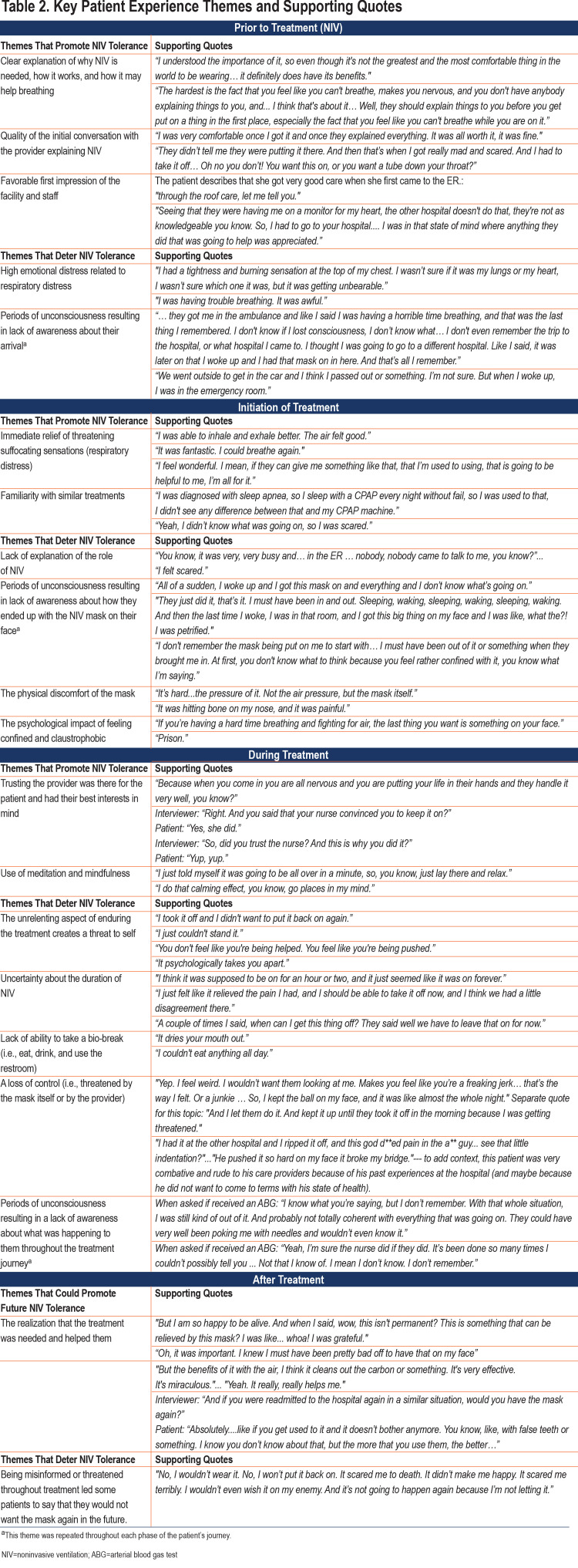

Phase 1, the prior to NIV treatment phase, had the highest variability in the emotions expressed by patients (32% positive, 20% neutral, and 48% negative), and included 3 steps: (1) prior awareness of ventilation, (2) arrival to the hospital, and (3) provider explanation of the NIV (Table 1).

Themes that promote NIV tolerance included:

a. The first impression of the facility and staff had a great impact on the patient’s perception of their treatment. Those who had a good first encounter with the staff or knew about the hospital’s reputation in the community were more likely to describe positive emotions of their journey, including trust in providers and feeling safe.

b. The quality of the initial conversation with the provider explaining NIV influenced the patient’s perception of the treatment and impacted their entire experience. Some patients felt threatened when discussing alternatives, especially regarding intubation, whereas others felt grateful that there was a less invasive alternative.

c. Clear explanation of why NIV is needed, how it works, and how it may help breathing. Patients whose provider explained what to expect with the NIV mask, the benefits of NIV, and alternatives to NIV, felt included, informed, and ready for treatment; they were more likely to “put up” with the discomfort caused by the mask. Patients who arrived in a distressed or confused state often missed this step and had a more negative experience.

Themes that deter NIV tolerance included:

d. High emotional distress related to respiratory distress. Patients who presented with labored breathing were in a highly charged, emotionally distressed state due to the threatening suffocating sensations and had a more negative outlook on their experience.

e. Periods of unconsciousness resulting in a lack of awareness about their arrival. Some patients were not aware of what was happening to them when they arrived at the hospital. When they became alert, they did not understand their situation and became scared about having the mask on their face.

Phase 2: Initiation of NIV Treatment Phase

Phase 2, the initiation of NIV treatment phase, had the highest percentage of negative emotions (78%)and included 3 steps: (1)initial reaction to the mask, (2) physical sensation with the NIV mask, and (3) breathing sensation.

Themes that promote NIV tolerance included:

a. The immediate relief of suffocating sensations (respiratory distress). Some patients reported that NIV helped them breathe better immediately, taking little time for the treatment to alleviate their respiratory distress. In contrast, delayed relief of suffocating sensations left many patients feeling like they were not getting better with NIV.

b. Familiarity with similar treatments. Those who have OSA and used CPAP, and those who successfully used NIV in a prior admission, experienced a neutral or positive emotion. They were familiar with the machine’s functionality and knew it could help their breathing.

Themes that deter NIV tolerance included:

c. Lack of explanation of the role of NIV (the opposite of what is explained in phase 1, theme c)

d. Periods of unconsciousness resulting in a lack of awareness about how they ended up with the NIV mask on their face (similar with phase 1, theme e)

e. The physical discomfort of the mask. The fit around the nose was specifically called out by multiple patients, along with the mask’s tightness, restriction, and pressure on the face. Many patients also described other physical aspects of the treatment, such as dry mouth and not being able to eat.

f. The psychological impact of feeling confined and claustrophobic with the mask on their face was reported by many patients.

Phase 3: During NIV Treatment

Phase 3, the during NIV treatment phase, is associated with the most emotions expressed by patients compared to the other 3 phases (57 distinct emotions compared to the next highest of 29 distinct emotions in phase 4). Steps included in this phase are: (1) how the patient felt while receiving NIV, (2) patient interactions with providers and staff and (3) family/ friends’ role.

Themes that promote NIV tolerance include:

a. Trusting the provider was there for the patient and had their best interest put some patients at ease resulting in a more positive experience.

b. The use of meditation and mindfulness helped patients relax and endure the treatment, even if they felt the treatment was uncomfortable. These patients reported their experience as a controllable state of mind.

Themes that deter NIV tolerance include:

c. The unrelenting aspect of enduring the treatment creates a threat to self. Whether the patient understood what the mask was for or not, patients reported that this treatment was uncomfortable and scary.

d. The uncertainty about the duration of NIV put many patients on edge. Not knowing how long they needed to keep this uncomfortable mask on their face made the patients anxious. Some took the mask off and did not want to accept it again.

e. The lack of the ability to take a bio-break (i.e., eat, drink, and use the restroom) made the experience of the mask intensely miserable for patients who needed to wear the mask for extended periods.

f. Loss of control. The presence of the mask as a life-saving device was felt by some patients as a danger to their autonomy and independence, especially when they requested breaks and the provider threatened them with intubation, which led to fear and mistrust and a more negative experience.

Phase 4: After NIV Treatment

Phase 4, the after NIV treatment phase, was the phase with the second-highest emotions expressed and was dominated by 86% positive emotion. The steps identified in this phase were: (1) experience with removal of the mask; (2) reflection on NIV importance; and (3) overall feelings after treatment.

Themes that could promote future NIV tolerance include:

a. The realization that the treatment was needed and helped them. Most patients were grateful that the treatment was successful and that they were no longer in respiratory distress. They reported feeling relieved, free, and grateful. At this point in their journey, most patients realized that the treatment was needed and helped them.

Themes that deter NIV tolerance include:

b. Being misinformed or threatened throughout treatment led some patients to say that they would not want the mask again in the future. Some patients had a bad overall experience which overshadowed the fact that the treatment worked. Regardless of the positive outcome, the patient still would decline NIV in the future.

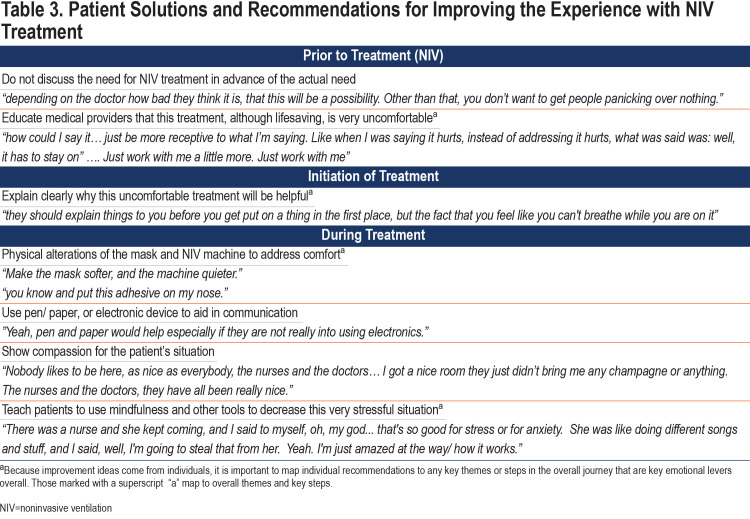

Patient recommendations for improving tolerance: Patient solutions and recommendations for improving the experience of NIV treatment are described in Table 3.

Discussion

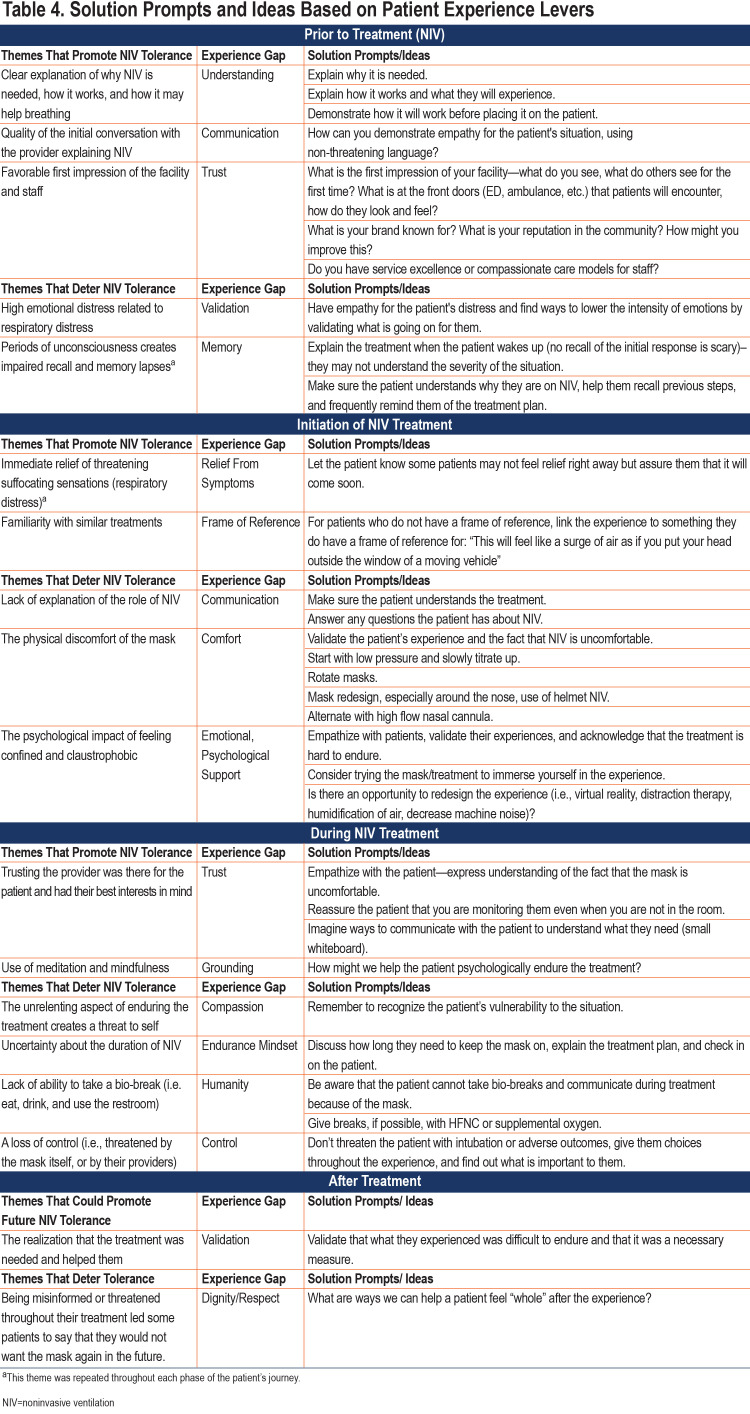

Although there is strong evidence that NIV improves the outcomes of patients with severe COPD exacerbation and that NIV intolerance is associated with increased risk for intubation, only a few studies have considered the patient experience while using NIV.8,14 In this qualitative study, we used an HCD methodology and sampled a cohort of patients with COPD treated with NIV to understand patients' journey with the future goal of improving NIV tolerance.1,2,18-20 We broke the patient journey into 4 phases such that potential solutions to problems could be more actionable (Table 3). We found that except for the last phase, when the mask was removed and patients reflected on the importance of NIV on their outcome, all the other phases were highly charged with negative emotions.

Several themes dominated the interviews. The discomfort with the mask itself was not surprising. Like other studies, we found that patients find the mask uncomfortable, and many reported psychological/emotional distress. They felt confined and scared while treated with NIV. Some were frightened by the loss of control. These findings are consistent with reports of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms the patients with acute respiratory failure describe after being treated in the intensive care unit (ICU).27,28 Patients had several suggestions to improve the mask and make it more tolerable, which is summarized in this quote: “make it softer, make it quieter; put an adhesive on my nose.” Some suggested the need for electronic devices for communication. Companies that develop NIV masks should include patients in their design team and test various models on patients while simulating respiratory distress.

Notably, patients who understood how NIV works, what they will feel, and its scope, were more likely to bear the physical and emotional discomfort. For example, patients who used CPAP/NIV for OSA were more likely to have a positive experience. Patients made a strong point about the need for an explanation on why NIV is started when they are in respiratory distress. A pressurized tight-fitting mask is not what one expects to help their breathing. Iosifan et al provided patients with detailed information prior to NIV treatment and most patients did not have anticipatory anxiety or fear.16 In our study, patients reported that discussing this therapy before it is needed is not necessarily good because it could inflict more fear for the future. This is similar to the findings of Beckert et al and Lemoigan et al that suggested patients do not want information about their treatment before it is needed to make decisions, because information tends to discourage them.15,29

The interaction with providers, level of trust, quality of the discussion when initiating or persuading the patient to keep the mask in place, and the initial perception of the medical care had a significant impact on how the patient experienced NIV. Patients who perceived being threatened with intubation had their journey dominated by negativity and did not accept NIV for future treatments. Therefore, it is critical to educate medical providers that this treatment, although life-saving, is uncomfortable and could explain patients’ resistance.30 Patients suggested that providers need to be more sympathetic and receptive to their physical and emotional distress. The most impactful interaction that patients remembered was with nurses. A survey of nurses regarding the management of patients treated with NIV has shown that most nurses felt unprepared to care for these sick patients. Nurses need to be educated on the technical aspects of therapy and equipment as well as factors influencing tolerance. 31,32

One theme that dominated the journey and spanned multiple phases was the impaired recall of various events while treated with NIV. Many patients did not recall having NIV started; they awakened with the mask on their face and were frightened. Frequently, providers enter the room and are happy to see that the patient is alert, but do not explain why they are receiving NIV and how long the mask will need to be worn. As a result, patients become anxious, disoriented, feel dismissed and ignored, and their entire experience can be traumatic. Refining how providers interact with patients and making them aware of these issues could humanize the experience and dissipate the distress.

Some patients recommended using mindfulness to decrease this very stressful situation. Non-pharmacological therapies are more recently investigated to improve discomfort with NIV. A study evaluating the effect of a musical intervention for respiratory comfort during NIV in the ICU reported that it decreases peri-traumatic symptoms at ICU discharge but did not reduce respiratory discomfort during NIV for acute respiratory failure in comparison to conventional care.33 Further non-pharmacological interventions including mindfulness should be evaluated.

The experience gaps for the themes are the pieces missing from patient care that could make the patient’s experience more tolerable (Table 4). However, it is not known if improving the patient perspective, which although it is very important, will reduce intubation rates and mortality. Future studies should determine if strategies addressing the problems we uncovered will improve outcomes, and which strategies are the most suitable (Table 4).

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

Our study investigated the experience of patients with COPD with NIV treatment in the United States using HCD methodology and focused on the user perspective. A potential weakness of our study is the memory bias related to the impaired recall of the acute events during hospitalization, and the recollection bias as the interviews were performed sometimes several days after NIV use. The study setting and the fact that it was performed during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic made both patient recruitment and the interviews highly demanding and there was some variability in the way interviews were performed. This study was conducted in a single institution and the management of patients with COPD on NIV could reflect the local culture. We do not know if the results would have been the same with different caregivers, different staffing levels, different interfaces, or different approaches to NIV.

Conclusions

We identified several main themes which influence patient tolerance to NIV: information/explanation about NIV role, quality of interaction with health care providers, physical and emotional discomfort including fear of the technology/mask, impaired recall, and familiarity with similar treatment. Understanding the reality of patients with COPD treated with NIV will help refine strategies that can improve their experience and tolerance with NIV. Future research should test ideas with the best potential, generate prototypes, and design iterations to be tested with patients.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations: human-centered design, HCD; noninvasive ventilation, NIV; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; obstructive sleep apnea, OSA; continuous positive airway pressure, CPAP; arterial blood gas test, ABG; intensive care unit, ICU; coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19

Funding Statement

Grant funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Grant number: 1R01HL146615

References

- 1.May SM,Li JTC. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: healthcare costs and beyond. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36(1):4-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2015.36.3812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindenauer PK,Dharmarajan K,Qin L,Lin Z,Gershon AS,Krumholz HM. Risk trajectories of readmission and death in the first year after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(8):1009-1017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201709-1852OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrini L,Landoni G,Oriani A,et al. Noninvasive ventilation and survival in acute care settings: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):880-888.doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brochard L,Mancebo J,Wysocki M,et al. Noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(13):817-822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199509283331301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lightowler JV,Wedzicha JA,Elliott MW,Ram FSF. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to treat respiratory failure resulting from exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):185. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7382.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keenan SP,Sinuff T,Cook DJ,Hill NS. Which patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease benefit from noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation? A systematic review of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):861-870. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochwerg B,Brochard L,Elliott MW,et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02426-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra D,Stamm JA,Taylor B,et al. Outcomes of noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United States, 1998-2008. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(2):152-159. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201106-1094OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moretti M,Cilione C,Tampieri A,Fracchia C,Marchioni A,Nava S. Incidence and causes of non-invasive mechanical ventilation failure after initial success. Thorax. 2000;55(10):819-825. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.55.10.819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonelli M,Conti G,Moro ML,et al. Predictors of failure of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a multi-center study. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(11):1718-1728. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-001-1114-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demoule A,Girou E,Richard JC,Taille S,Brochard L. Benefits and risks of success or failure of noninvasive ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(11):1756-1765. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-006-0324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedsund C,Ankjærgaard KL,Rasmussen DB,et al. NIV for acute respiratory failure in COPD: high in-hospital mortality is determined by patient selection. Eur Clin Respir J. 2019;6(1):1571332.doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/20018525.2019.1571332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ucgun I,Metintas M,Moral H,Alatas F,Yildirim H,Erginel S. Predictors of hospital outcome and intubation in COPD patients admitted to the respiratory ICU for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure. Respir Med. 2006;100(1):66-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J,Duan J,Bai L,Zhou L. Noninvasive ventilation intolerance: characteristics, predictors, and outcomes. Respir Care. 2016;61(3):277-284.doi: https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.04220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckert L,Wiseman R,Pitama S,Landers A. What can we learn from patients to improve their non-invasive ventilation experience? "It was unpleasant; if I was offered it again, I would do what I was told". BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(1):e7.doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iosifyan M,Schmidt M,Hurbault A,et al. "I had the feeling that I was trapped": a bedside qualitative study of cognitive and affective attitudes toward noninvasive ventilation in patients with acute respiratory failure. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):134.doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0608-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith TA,Davidson PM,Jenkins CR,Ingham JM. Life behind the mask: the patient experience of NIV. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(1):8-10.doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70267-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harte R,Glynn L,Rodríguez-Molinero A,et al. A human-centered design methodology to enhance the usability, human factors, and user experience of connected health systems: a three-phase methodology. JMIR Hum Factors. 2017;4(1):e8. doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/humanfactors.5443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henninger ML,Mcmullen CK,Firemark AJ,Naleway AL,Henrikson NB,Turcotte JA. User-centered design for developing interventions to improve clinician recommendation of human papillomavirus vaccination. Perm J. 2017;21:16-191. doi: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattacharyya O,Mossman K,Gustafsson L,Schneider EC. Using human-centered design to build a digital health advisor for patients with complex needs: persona and prototype development. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(5):e10318.doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/10318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langley J,Wolstenholme D,Cooke J. "Collective making" as knowledge mobilisation: the contribution of participatory design in the co-creation of knowledge in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):585. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3397-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenhalgh T,Jackson C,Shaw S,Janamian T. Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):392-429.doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papautsky EL,Strouse R,Dominguez C. Combining cognitive task analysis and participatory design methods to elicit and represent task flows. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2020;14(4):288-301.doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343420976014 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carayon P,Wooldridge A,Hoonakker P,Hundt AS,Kelly MM. SEIPS 3.0: human-centered design of the patient journey for patient safety. Appl Ergon. 2020;84:103033. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2019.103033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. General Services Administration Office of Customer Experience, The Lab at Office of Personnel Management. Human-Centered Design (HCD) Discovery Stage Field Guide. 2017;18. Accessed October 2021. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/HCD-Discovery-Guide-Interagency-v12-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Risk Authority Future Medical Systems. Discovery Design: Design Thinking for Healthcare Improvement. The Risk Authority. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teixeira C,Rosa RG,Sganzerla D,et al. The burden of mental illness among survivors of critical care-risk factors and impact on quality of life: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Chest. 2021;160(1):157-164. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith S,Rahman O. Post Intensive Care Syndrome. In. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022. Accessed October 18, 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558964/

- 29.Lemoignan J,Ells C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and assisted ventilation: how patients decide. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8(2):207-213. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951510000027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen HM,Titlestad IL,Huniche L. Development of non-invasive ventilation treatment practice for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a participatory research project. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:1-5.doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312117739785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts A. Understanding the principles of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. Nurs Stand. 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2021.e11750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehlmann H,Ochmann T. Erleben unter nichtinvasiver beatmung (NIV) durch pflege beeinflussen. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2021;116:702-707. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00063-021-00836-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messika J,Martin Y,Maquigneau N,et al. A musical intervention for respiratory comfort during noninvasive ventilation in the ICU. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01873-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This article contains supplemental material.