Abstract

Aim: Previously, we found that diabetes-related liver dysfunction is due to activation of the 5-HT 2A receptor (5-HT 2A R) and increased synthesis and degradation of 5-HT. Here, we investigated the role of 5-HT in the development of atherosclerosis.

Methods: The study was conducted using high-fat diet-fed male ApoE −/− mice, THP-1 cell-derived macrophages, and HUVECs. Protein expression and biochemical indexes were determined by Western blotting and quantitative analysis kit, respectively. The following staining methods were used: oil red O staining (showing atherosclerotic plaques and intracellular lipid droplets), immunohistochemistry (showing the expression of 5-HT 2A R, 5-HT synthase, and CD68 in the aortic wall), and fluorescent probe staining (showing intracellular ROS).

Results: In addition to improving hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, co-treatment with a 5-HT synthesis inhibitor and a 5-HT 2A R antagonist significantly suppressed the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and macrophage infiltration in the aorta of ApoE −/− mice in a synergistic manner. Macrophages and HUVECs exposed to oxLDL or palmitic acid in vitro showed that activated 5-HT 2A R regulated TG synthesis and oxLDL uptake by activating PKCε, resulting in formation of lipid droplets and even foam cells; ROS production was due to the increase of both intracellular 5-HT synthesis and mitochondrial MAO-A-catalyzed 5-HT degradation, which leads to the activation of NF-κB and the release of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β from macrophages and HUVECs as well as MCP-1 release from HUVECs.

Conclusion: Similar to hepatic steatosis, the pathogenesis of lipid-induced atherosclerosis is associated with activation of intracellular 5-HT 2A R, 5-HT synthesis, and 5-HT degradation.

Keywords: 5-HT synthesis, 5-HT2A receptor, Monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), 5-HT degradation, Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

See editorial vol. 29: 315-316

Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS), a common disease, is the principal pathological basis of ischemic cardiocerebrovascular disease, characterized by the accumulation of lipid and inflammatory cells in the walls of medium- and large-sized arteries 1) . Although the pathogenesis of AS is still unclear, AS involves the activation of cytokine/chemokine expression and oxidative stress caused by excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) 2) . Low density lipoprotein (LDL) is oxidized to form oxidized LDL (oxLDL) in AS. OxLDL stimulates endothelial cells (ECs) to release cell adhesion molecules, chemotactic proteins (such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1]), eotaxin, etc., which leads to the recruitment of leukocytes (mainly monocytes and T lymphocytes) into the subendothelial space, which then migrate to the vascular intima 3) . Macrophages differentiated from monocytes phagocytose modified lipoproteins and express scavenger receptors (SRs), such as CD36 and SRA, forming foam cells. These lipid-rich cells are found in the arterial walls and are a marker of early AS lesions 4) . Macrophages are transformed into foam cells, which are the principal contributors to the development of AS by secreting pro-inflammatory mediators (chemokines, cytokines, ROS, etc.) and matrix-degrading proteases 5) . Therefore, macrophage recruitment, foam cell formation, oxidative stress induced by ROS overproduction, and release of inflammatory cytokines are typical characteristics of AS lesions in the arterial wall.

Serotonin (5-HT) is an important bioactive molecule involved in a variety of central and peripheral functions 6) . It is an extracellular mediator, and its receptors can be divided into seven classes (5-HT 1–7 R), which can give rise to distinct intracellular responses 7) . It was found that 5-HT plays a key role in the development of AS, including platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction, proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), EC function, and formation of macrophage foam cells 8) . As a selective 5-HT 2 R antagonist (mainly against 5-HT 2A R), sarpogrelate can inhibit the development of AS 9) by inhibiting the expression of acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase-1 in macrophages 10) , vascular oxidative stress, and VSMC proliferation 11) . However, the role of 5-HT in AS remains unclear.

Peripheral 5-HT was synthesized from L-tryptophan by two-step catalysis of tryptophan hydroxyl 1 (TPH1) (first step) and aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) (second step). It is believed that the synthesis site of blood 5-HT is mainly in the enterochromaffin cells of the gastrointestinal tract 12) . However, we found that 5-HT can also be synthesized by hepatocytes, which plays a pivotal role in the formation of hepatic steatosis. By acting on 5-HT 2A R, 5-HT is involved in the molecular mechanism of excess lipid synthesis induced by saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and glucocorticoids, including excessive production of triglycerides (TGs) and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), and accumulation of lipid droplets in hepatocytes 13 - 16) . We have previously reported how the 5-HT system regulates lipid synthesis and inflammatory cytokine production in SFA-treated hepatocytes; it involves 5-HT 2A R-mediated lipid synthesis and mitochondrial 5-HT degradation catalyzed by monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), which leads to an increase in mitochondrial ROS production 16) .

Interestingly, here we found that the development of AS is also associated with 5-HT. Specifically, it includes 5-HT 2A R activation and 5-HT degradation in macrophages, 5-HT degradation in vascular ECs, and 5-HT synthesis in both types of cells. To investigate the mechanism through which the 5-HT system mediates AS-associated pathological changes, human acute monocytic leukemia (THP-1) cell-derived macrophages and human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) were cultured in vitro and treated with palmitic acid (PA) and oxLDL. In addition, apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE −/− ) mice were fed with a high-fat diet (HFD) to establish the AS model. These mice were then treated with or without 5-HT synthesis inhibitors and 5-HT 2A R antagonists (alone or in combination) to observe the therapeutic effects of inhibiting peripheral 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT 2A R on AS lesions.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of AS Model and Drug Treatment

ApoE −/− and C57BL/6J male mice (4–6 weeks old) were bred by the Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China), and were housed in a 12-h light/dark cycle with access to water and food ad libitum. The proposed animal study was approved by the China Pharmaceutical University Animal Use and Care Committee, and carried out in accordance with the Guide for Laboratory Animal Management and Application printed by China Pharmaceutical University.

The AS mouse model was established according to Grandoch et al. 17) . Briefly, ApoE −/− mice were fed with HFD (containing 19.5% protein [w/w], ≥ 49% carbohydrates, 22.5% fat, 0.5% cholesterol) for 16 weeks, inducing AS lesions, and C57BL/6J mice were fed with regular chow food. In the end, three ApoE −/− mice were randomly selected and anesthetized with amobarbital sodium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and euthanized. Aortas were taken and stained with oil red O to confirm the presence of AS lesions.

As described in previous studies 16) , carbidopa (CDP; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Tokyo, Japan), an AADC inhibitor, was used to inhibit the synthesis of peripheral 5-HT, and sarpogrelate hydrochloride (SH) (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) was used as a 5-HT 2A R antagonist. For the combination of SH and CDP (SC), the SH/CDP ratio was 2:1, which made the molar dose of the two compounds in SC equal (molecular weight of SH and CDP are 465 and 226, respectively). All ApoE −/− mice, which had been fed with HFD for 16 weeks, were randomly divided into four groups, and C57BL/6J mice were set as the control group (Ctrl), eight mice in each group. Ctrl mice continued being fed with regular chow food, while ApoE −/− mice continued being fed with HFD. ApoE −/− mice were given SH and CDP (alone or in combination) by gavage, while control mice and AS model ApoE −/− mice were given 0.5% CMC-Na by gavage. In the three drug-treated groups, the same dose of 30 mg/kg/time was given twice a day for 6 weeks. Body weight and food intake were recorded weekly.

In the 6 th week of treatment, after fasting for 12 h and drug administration for 4 h, glucose tolerance test (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) were performed. Finally, 12 h after fasting, fasting blood glucose (FBG) was measured using a blood glucose meter (Sinocare Inc., Changsha, China). Then, all mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of amobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg). The serum was collected and the mice were euthanized. The heart and aortic trees were perfused with normal saline to remove remaining blood and stains. The liver, aortic tree, and heart were isolated. The liver was weighed and the liver index (percentage of body weight) was calculated. One piece of liver tissue from each mouse and three hearts in each group were immediately fixed in 10% neutral formalin. The rest of the liver tissue, serum samples, and hearts were stored at −80℃ until further processing and analysis.

THP-1 Cell-Derived Macrophages and HUVECs Culture

THP-1 cells were obtained from the Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), and HUVECs from the American Type Culture Collection (USA). THP-1 and HUVECs were cultured in RPMI-1640 or DMEM medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Zhejiang Tianhang Biotechnology, Hangzhou, China) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and maintained at 37℃ in a 5% CO 2 atmosphere. THP-1 cells in logarithmic growth phase were cultured for 48 h using phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (100 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) to induce differentiation of THP-1 cells into adherent macrophages. After adherence, the supernatant cells were removed and macrophages were obtained. When treated, the cells were incubated in serum-free (to exclude the influence of serum 5-HT on the results) RPMI-1640 or DMEM containing antibiotics. After incubation for 1 h, the cells were treated with drugs (30 µM SH, 30 µM CDP, 30 µM para-chlorophenylalanine [pCPA] [ApexBio Technology LLC, Houston, TX, USA] and 10 µM clorgyline [CGL] [CSNpharm, Chicago, USA]or an equal-volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 24 h, then additionally exposed to the vehicle of irritant (50% isopropanol), oxLDL (150 µg/mL) (Yiyuan biotechnology, Guangzhou, China), 5-HT (50 µM), or PA (200 µM) (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively, according to each experiment.

GTT and ITT

Five mice in each group were randomly selected for GTT and ITT. A dose of 2 g/kg glucose injection (Hunan Kelun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Yueyang, China) or 0.5 IU/kg insulin injection (Eli Lilly Inc., Suzhou, China) for ITT was intraperitoneally injected for GTT and ITT. Approximately 20 µL of blood was sampled at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 150 min (GTT) or at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min (ITT) by tail bleeding before and after glucose/insulin was administered. Blood glucose was measured using a blood glucose meter (Sinocare Inc.). The change of glucose concentration in ITT was expressed as a percentage of basal glucose 18) . The GTT and ITT were evaluated by the total area under the blood glucose curve (AUC) using the trapezoidal method 19) .

Oil Red O Staining in the Aortic Inner Surface

Mouse aortas, which include the aortic arch, subclavian artery, abdominal aorta, and bilateral iliac arteries, were stained with oil red O. Briefly, the aorta was spread and fixed on a black rubber pad, fixed with 10% formalin, dehydrated with isopropanol, stained fresh oil red O working solution in a 60℃ incubator, and de-stained with 85% isopropanol and a brief rinse with distilled water. Finally, the stained aorta was immersed in saline solution, and analyzed under a 20× magnifying glass and photographed using a digital camera (COOLPIX S7000; Nikon Corporation, Shanghai, China). The distribution of AS plaques in the aorta was evaluated, and the AS lesions were quantified by Image J software. The lesion area was expressed as a percentage of the total aortic surface area (plaque area (%)=total plaque area / total aortic surface (cross-sectional) area×100%).CD68 (macrophages marker) area and AS plaque area in the aortic root cross-section were determined by immunohistochemistry and oil red O staining, respectively and were expressed as a percentage of the total aortic cross-sectional area (CD68 or AS plaque area (%)=total CD68 or AS plaque area / total aortic cross-sectional area×100%). Furthermore, the same method was used to determine the lipid droplet area in macrophages (lipid droplet area (%)=total lipid droplet area / total cellular area×100%).

Immunohistochemical Staining in the Aortic Root Cross-Section

Serial and 5-µm-thick paraffin-embedded cross-sections were dewaxed and then blocked in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min, blocked in 10% goat serum (Zhejiang Tianhang Biotechnology) at room temperature for 30 min, and incubated with anti-5-HT 2A R (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-5-HT 2B R, anti-Tph1 (Signalway Antibody, College Park, MD, USA), or anti-CD68 (Bioworld Technology, St Louis Park, MN, USA) antibodies, respectively, in blocking solution at 4℃ overnight. The sections were treated with secondary antibodies (HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG) for 1 hour at 37℃. Then, the sections were visualized with 3-3’-diaminobenzidine. Images were generated using an optical microscope (Monolith; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and the severity of AS in mice was analyzed using Image Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., USA). The CD68-stained area was quantified using Image J software.

Western Blot Analysis

Extraction of whole-cell, plasmalemma, cytosol, and nucleoplasm proteins was performed using a protein extraction kit (KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China). The protein concentration was determined with an enhanced BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) to calculate the loading amount. The samples were isolated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polypropylene fluoride membrane. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% bovine serum albumin for 2 hours at room temperature. After being washed with TBST, the membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies at 4℃ overnight, respectively. Then, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies. Immunopositive bands were visualized using ECL (Tanon-5200; China), and the protein bands were quantified by densitometry. Blotting against β-actin for cytosol, GAPDH for whole-cell proteins, and Na + -K + -ATPase for plasmalemma proteins were used as internal controls. The anti-5-HT 2A R antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-Tph1, anti-AADC, anti-MAO-A, anti-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1 (GPAT1), anti-microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, anti-IκBα, anti-NF-κB p65, and anti-ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 antibodies were from Signalway Antibody; anti-GAPDH, anti-phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536), and anti-phospho-IκBα (Ser32/Ser36) antibodies were from Wanleibio (Shenyang China); anti-PKCε and anti-β-actin antibodies were from Bioworld Technology; and anti-CD36 and anti-Na + -K + -ATPase antibodies were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (secondary antibody) was from AmyJet Scientific Inc (Wuhan, China).

Identification of Mitochondrial ROS and Localization of Mitochondria

The detection of ROS levels or co-localization of intracellular ROS and mitochondria was performed using the fluorescent dye DCFH-DA (Beyotime) or the combination of DCFH-DA and MitoTracker ® Red CMXRos, a mitochondria-specific probe (Yeasen, Shanghai, China), respectively. THP-1 cell-derived macrophages or HUVECs (1.0×10 6 cells/mL) were incubated in a laser confocal culture dish with MitoTracker ® Red CMXRos and/or DCFH-DA for 30 min in the dark at 37℃. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were examined under a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM700; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The excitation wavelengths for DCFH-DA and MitoTracker ® Red CMXRos were 488 and 579 nm, respectively, to detect ROS levels and ROS and mitochondria localization.

Oil red O Staining of the Aortic Root Cross-Section, Liver Tissue Sections, and Macrophages

A frozen aortic root slice or formalin-fixed liver tissue was cut into 6-µm-thick sections. The tissue sections or macrophages were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed with 60% isopropanol or PBS, respectively, and stained with freshly prepared oil red O working solution. They were then rinsed again with 60% isopropanol or PBS and finally counterstained with hematoxylin. The tissue sections or cells were examined under an optical microscope (Monolith; Olympus).

Detection of Biochemical Indicators Using an ELISA Kit or Enzyme-Test Kit

VLDL, HDL, L-dopamine, 5-HT, TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 levels in the liver tissue, medium, or cultured cells were assessed in a microplate using respective commercial ELISA kits (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) and a microplate reader (Infinite M200PRO; TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). The concentration of the indicators was calculated according to a standard curve. The indicators in liver tissue, medium, or cells were divided by the corresponding total protein level to obtain the final results.

Aspertate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities, total cholesterol (TC), TG (only in serum), free fatty acids (FFAs), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), and H 2 O 2 levels in the serum or cells and the total protein level in the tissue were assessed using respective commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) and a microplate reader (Infinite M200PRO; TECAN). The concentration of the indicators was calculated according to a standard curve. Serum very low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (VLDL-C) was calculated by TC−(LDL-C+HDL-C).

TG Analysis in Cells and Liver Tissue

The liver tissue and cell samples were heated at 70℃ for 10 min and centrifuged at 600×g for 5 min. The supernatant was used to determine the TG content. As per the instructions of the TG enzyme-test kit (ApplyGen, Beijing, China), the absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of 550 nm with a microplate reader (Infinite M200PRO; TECAN). The TG concentration was calculated according to a standard curve. TG concentration was divided by the corresponding protein concentration to obtain the final results.

Statistical Analysis

Data is expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by using Mann–Whitney U test for the AS plaque area in the aortic inner surface and cross-section of the aortic root, immunohistological staining area of CD68 in the cross-section of the aortic root, lipid droplet area in cells, and expressions of Tph1, AADC, 5-HT 2A R, and MAO-A. That of other data was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by the LSD test (if there is homogeneity of variance) or Dunnett’s test (if variance is uneven). P -values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

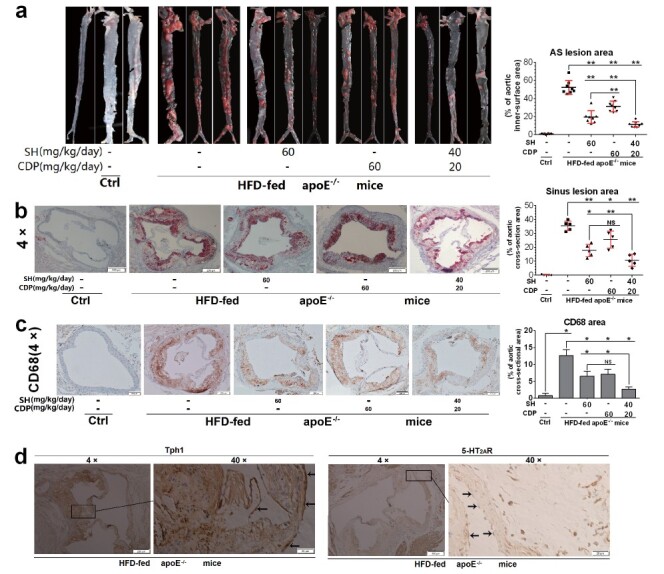

A Combination of both 5-HT Synthesis Inhibitor and 5-HT 2A R Antagonist Synergistically Prevents the Development of AS

AS lesions on the inner surface of the aortas ( Fig.1, a ) and the cross-section of the aortic root (sinus lesions) ( Fig.1, b ) were assessed by oil red O staining. The results showed that in ApoE −/− mice fed HFD, the average AS lesion area (also called AS plaque area) of the aortic inner surface and aortic root was 52% and 36%, respectively. SH (antagonist of 5-HT 2A R) and CDP (inhibitor of AADC) could significantly reduce AS lesions. Specifically, the AS lesion area in the aortic inner surface and aortic root cross-section was 20% and 17% (SH group), 31% and 26% (CDP group), and 11% and 10% (SC group, co-treatment with SH and CDP), respectively. These results indicated that SH had a stronger inhibitory effect on plaque formation than CDP, and there was a synergistic inhibition by SH and CDP combined. Immunohistochemistry was used to detect the expression of the macrophage marker CD68 in the cross-section of the aortic root ( Fig.1, c ) , and it was found that the abundance and distribution of macrophages were consistent with the severity and area of AS lesions. In addition, we found by immunohistochemistry that Tph1 and 5-HT 2A R were widely expressed in the aortic root and myocardial cross-section of ApoE −/− mice fed with HFD, while 5-HT 2A R expression was not detected in vascular ECs ( Fig.1, d ) .

Fig.1. Therapeutic effects of SH and CDP on atherosclerotic lesions in HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice .

Representative AS lesions (20×) and AS lesion area in the en face aortas (a, n =8) and in the aortic root cross-sections (4×) (b, n =5) (to occupy percentage of total area) determined by oil red O staining, respectively. CD68 expression in aortic root cross-sections (4×) and CD68 area (to occupy percentage of total cross-sectional area) (c, n =3) in control (Ctrl) and HFD-fed ApoE −/− with or without SH and CDP treatment (alone or in combination) mice, and Tph1 and 5-HT 2A R expression in HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice (4× and 40×) (d) determined by immunohistological staining (arrows indicate vascular ECs with Tph1 expression and without 5-HT 2A R expression). Vascular ECs are indicated with arrows. Data are presented as the mean±SD for lesion area. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01. Abbreviations: SH, sarpogrelate hydrochloride; CDP, carbidopa; AS, atherosclerotic.

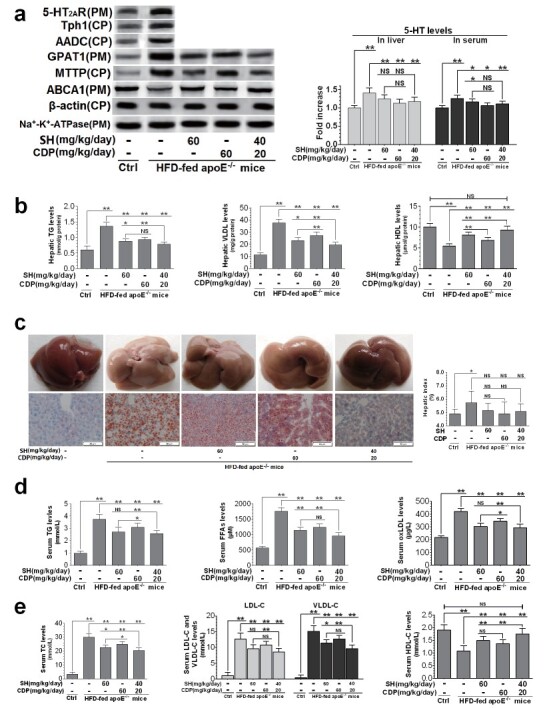

We then evaluated the pathological status of the liver, including the expression of 5-HT 2A R and 5-HT synthase in liver tissue and hepatic steatosis. In agreement with previous studies 14 , 16) , long-term HFD feeding resulted in increased liver Tph1, AADC, and 5-HT 2A R expression, as well as increased liver and serum 5-HT levels in ApoE −/− mice compared with control mice ( Fig.2, a ) . CDP and SH treatment significantly reduced liver and serum 5-HT levels ( Fig.2, a ) . At the same time, the expression of GPAT1, a rate-limiting enzyme synthesized by TG, and the rate-limiting microsomal triglyceride transfer protein assembled by VLDL were upregulated in the liver of ApoE −/− mice. However, the expression of ATP binding cassette transporter A1, which plays a key role in HDL biosynthesis 20) , was downregulated in the livers of HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice ( Fig.2, a ) , accompanied by an increase in TG and VLD levels and a decrease in HDL levels ( Fig.2, b ) . In addition, liver steatosis was obvious and hepatic index was increased ( Fig.2, c ) . SH and CDP combined treatment significantly improved the above liver pathological state in a synergistic manner.

Fig.2. Therapeutic effects of SH and CDP on hepatic steatosis and dyslipidemia in HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice .

Hepatic protein and 5-HT levels in the liver and serum (a), TG, VLDL, and HDL levels in liver (b), representative color photo of liver and histopathological findings of hepatic lipid droplets determined by oil red O staining (20×), and hepatic index (c), and serum levels of TG, FFAs, oxLDL (d), TC, LDL-c, VLDL-c, and HDL-c (e) in control (Ctrl) and HFD-fed ApoE −/− with or without SH and CDP treatment (alone or in combination) mice. Data are presented as the mean±SD of four mice chosen randomly for the examination of protein expression and of eight mice for the measurement of other indicators in each group. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01. Abbreviations: NS, not significant; SH, sarpogrelate hydrochloride; CDP, carbidopa; CP, cytoplasm; PM, plasmalemma

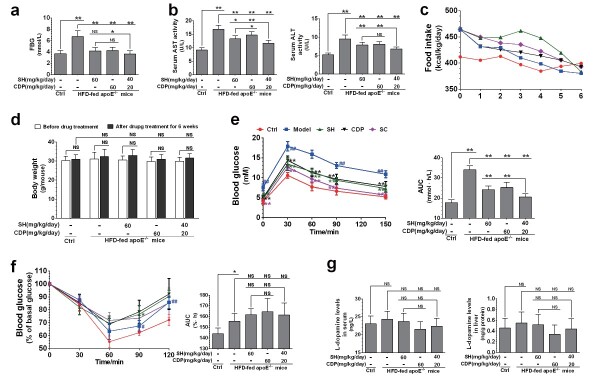

ApoE −/− mice fed HFD showed severe dyslipidemia. The levels of serum TG, FFAs, oxLDL, TC, LDL-C, and VLDL-C were significantly increased, while those of HDL-C were significantly decreased ( Fig.2, d and e ) . In particular, FFAs, TC, LDL-C, and VLDL-C levels were greatly increased. These dyslipidemia indexes could be reversed by SH and CDP in a synergistic manner. In addition, SH and CDP also significantly reduced the FBG levels ( Fig.3, a ) and inhibited the increase of AST and ALT activities ( Fig.3, b ) in HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice in a synergistic manner. However, compared with HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice, the food intake and body weight were not significantly changed in these three drug-treated groups ( Fig.3, c and d ) .

Fig.3. FBG, AST, and ALT activity, food intake, and body weight in HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice .

FBG (a), serum AST and ALT activity (b), food intake (c), body weight (d), glucose tolerance test (GTT) with blood glucose levels (left) and area under the blood glucose curve (AUC, right) (e), and insulin tolerance test (ITT) with blood glucose levels (left) and AUC (right) (f), L-dopamine levels (g) in control (Ctrl), and HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice (Model) and in SH-, CDP-, and SH+CDP (SC)-co-treated mice. Data are presented as the mean±SD. Except for five of eight per group in GTT and ITT, the others were from all eight rats per group. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01; ## P <0.01 vs. Ctrl and ** P <0.01 vs. Model in GTT and ITT. Abbreviations: NS, not significant; SH, sarpogrelate hydrochloride; CDP, carbidopa.

In GTT, compared with the control mice, HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice showed more significant increases in blood glucose levels ( Fig.3, e , left) and AUC ( Fig.3, e , right) within 150 min of intraperitoneal injection of glucose, suggesting that glucose intolerance had occurred. This glucose intolerance could be significantly reversed by SH and CDP treatment, and the combination of both drugs was more effective. By ITT, we found that the insulin tolerance was impaired in the HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice. The percentage of basal glucose ( Fig.3, f , left) and AUC ( Fig.3, f , right) in the model group were elevated at 90 and 120 min after intraperitoneal injection of insulin compared with the Ctrl group. On the contrary, treatment with SH and CDP (alone or in combination) did not reduce the percentage of basal glucose and AUC within 120 min after intraperitoneal injection of insulin compared with the model group. The results suggested that the insulin resistance (IR) was not ameliorated by SH and CDP in the HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice, though glucose intolerance was ameliorated 21) . In addition, there was no significant change in the serum and liver L-dopamine levels in ApoE −/− mice with or without SH and CDP treatment (alone or in combination) compared with the Ctrl mice ( Fig.3, g ) .

The Formation of Macrophage Foam Cells Induced by oxLDL Depends on the Activation of 5-HT 2A R and Increase of 5-HT Degradation

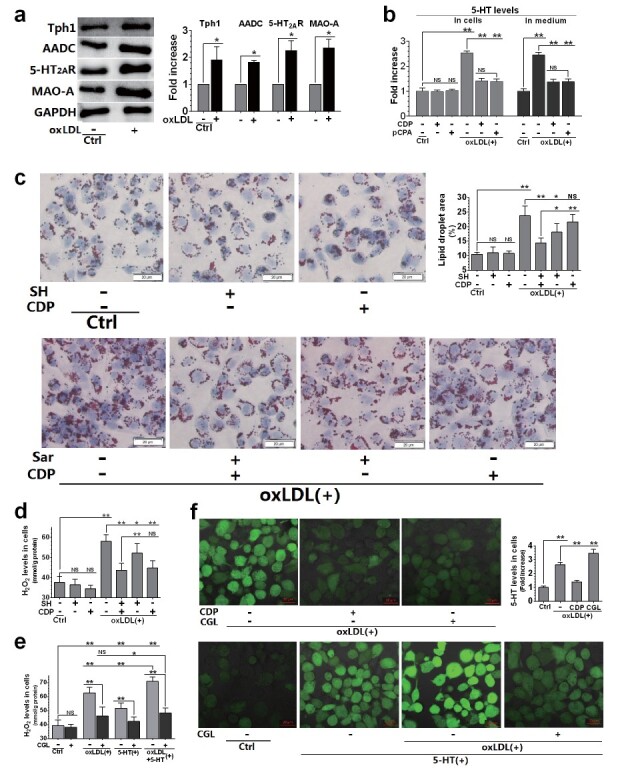

OxLDL is considered as a very important stimulator of foam cell formation in the pathogenesis of AS 22) . We therefore studied the effect of oxLDL on THP-1 cell-derived macrophage foam cell formation and its relationship with activation of 5-HT system. The expression of Tph1, AADC, and 5-HT 2A R was upregulated in macrophages exposed to oxLDL. OxLDL also led to the upregulation of MAO-A, an enzyme that degrades 5-HT ( Fig.4, a ) . The 5-HT levels in cells and medium were also measured ( Fig.4, b ) . The AADC inhibitor CDP and the Tph1 inhibitorpCPA significantly inhibited oxLDL-induced increase of 5-HT levels in cells and media, and showed the same effect when cells were treated with the same molar concentration ( Fig.4, b ) . The results showed that macrophages expressed the 5-HT system, including the 5-HT synthases Tph1 and AADC, the 5-HT receptor 5-HT 2A R, and the 5-HT degrading enzyme MAO-A. Their expression was upregulated when cells were exposed to oxLDL.

Fig.4. Relationship between 5-HT system activation and oxLDL-induced foam cell formation in THP-1 cell-derived macrophages.

Macrophages were treated with SH (30 µM), CDP (30 µM), pCPA (30 µM), CGL (10 µM), oxLDL (150 µg/mL), and 5-HT (50 µM). The cells were pre-treated with each drug for 24 h, followed by oxLDL and 5-HT treatment (alone or in combination) for another 12 h (a, b, and d–f) or 24 h (c). Whole-cell protein levels and their densitometric analysis of Tph1, AADC, 5-HT 2A R and MAO-A were evaluated using the western blot (with GAPDH as the loading control) (a). ELISA was used to measure intracellular and extracellular 5-HT levels (b, f). Representative lipid droplets determined by oil red O staining (40×) and lipid droplet area (%) (c). H 2 O 2 levels in cells(d-e). ROS distribution determined by fluorescent dye staining (20×) (f). Data are presented as the mean±SD of at least four independent experiments. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01. Abbreviations: NS, not significant; SH, sarpogrelate hydrochloride; CDP, carbidopa; pCPA, para-chlorophenylalanine; CGL, clorgyline.

To determine the role of 5-HT and 5-HT 2A R in oxLDL-induced foam cell formation, macrophages exposed to oxLDL were treated with CDP and SH (alone or in combination). We found that the effects of SH and CDP on oxLDL-induced foam cell formation were significantly different. SH increased the number of lipid droplets induced by oxLDL and increased the area of these droplets, that is, the formation of foam cells, suggesting that 5-HT 2A R mediates oxLDL-induced foam cell formation ( Fig.4, c ) . However, SH had a weak inhibitory effect on the increase of H 2 O 2 induced by oxLDL ( Fig.4, d ) . On the contrary, CDP strongly inhibited the production of H 2 O 2 induced by oxLDL, while the inhibitory effect on lipid droplet formation was weak ( Fig.4, c and d ) . More importantly, SH and CDP had synergistic inhibitory effects on lipid droplet formation induced by oxLDL. Based on our previous studies 16) , we concluded that oxLDL-induced H 2 O 2 production was due to the degradation of 5-HT by MAO-A in macrophage mitochondria. Hence, we observed the inhibitory effect of CGL, a MAO-A inhibitor, on H 2 O 2 production induced by 5-HT and oxLDL (alone or in combination) in macrophages. 5-HT aggravated oxLDL-induced H 2 O 2 production, while CGL strongly inhibited this effect ( Fig.4, e ) . We found that oxLDL and 5-HT (alone or in combination) increased intracellular ROS levels, which were significantly inhibited by CDP or CGL treatment ( Fig.4, f ) . Specifically, CDP significantly inhibited ROS production induced by oxLDL, while CGL strongly inhibited ROS production induced by oxLDL and oxLDL+5-HT. However, CDP and CGL had opposite effects on intracellular 5-HT levels. CDP inhibited the increase of intracellular 5-HT induced by oxLDL, while CGL exacerbated it ( Fig.4, f ) . These results suggest that the increase of both 5-HT synthesis and mitochondrial 5-HT degradation led to an increase in ROS production in macrophages exposed to oxLDL.

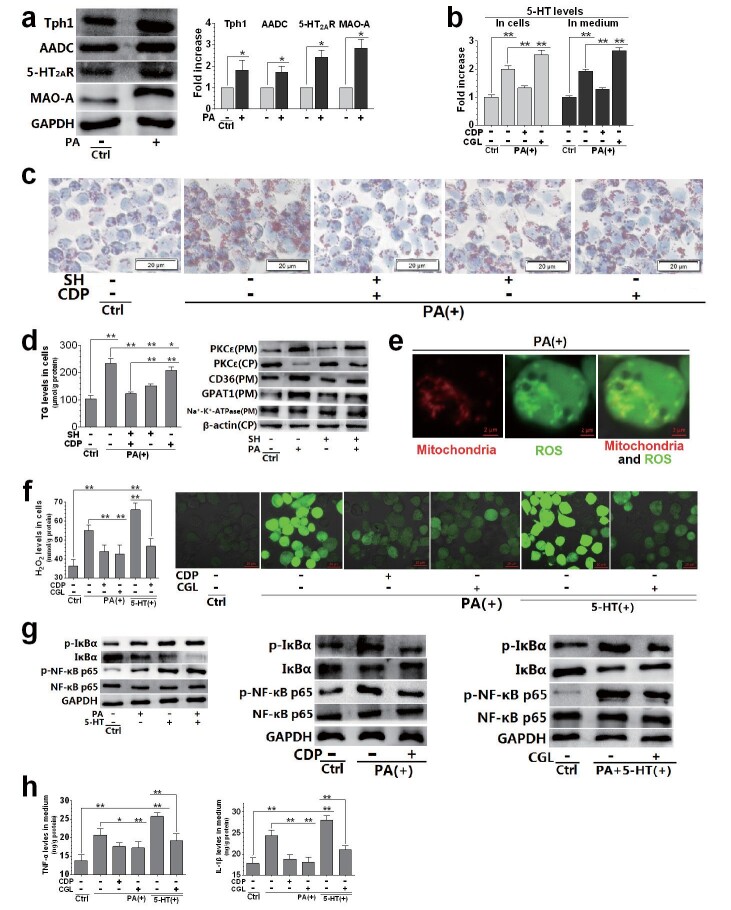

PA-Induced Lipid Droplet Formation also Depends on 5-HT 2A R Activation and 5-HT Degradation in Macrophages

SFAs are another risk factor for the development of AS. We examined whether PA and oxLDL induce the increase of intracellular TG synthesis and lipid droplet formation in a similar manner. We found that, similar to oxLDL, PA upregulated the expression of Tph1, AADC, 5-HT 2A R, and MAO-A ( Fig.5, a ) in macrophages and increased intracellular and extracellular 5-HT levels ( Fig.5, b ) . CDP treatment significantly inhibited PA-induced 5-HT elevation, but CGL treatment aggravated this elevation ( Fig.5, b ) . For PA-induced lipid droplet formation, SH also inhibited the increase of intracellular lipid droplets ( Fig.5, a and c ) and the increase of TG levels ( Fig.5, d ) . The effect of CDP was very weak, but together, CDP and SH had a synergistic inhibitory effect. We further measured the activation of PKCε (a protein kinase activated by 5-HT 2A R to regulate lipid synthesis 16) ) , CD36 (a key SR combined with oxLDL to promote its entry into cells 23) ), and GPAT1 (a rate-limiting enzyme for TG synthesis 24) ). We found that PA upregulated the expression of PKCε, CD36, and GPAT1 in the plasmalemma, but downregulated the expression of PKCε in the cytoplasm, and these effects of PA could be significantly inhibited by SH ( Fig.5, d ) . These results suggest that PA-induced lipid droplet formation is also mediated by activation of 5-HT 2A R, which in turn activates PKCε, thus regulating the expression of CD36 and GPAT1 on the plasmalemma, leading to increased lipid uptake and TG synthesis.

Fig.5. Relationship between 5-HT system activation and PA-induced dysfunctions in THP-1 cell-derived macrophages.

Macrophages were treated with SH (30 µM), CDP (30 µM), CGL (10 µM), PA (200 µM), and 5-HT (50 µM). The cells were pre-treated with each drug for 24 h, followed by PA and 5-HT treatment (alone or in combination) for another 12 h. Whole-cell protein levels and their densitometric analysis of Tph1, AADC, 5-HT 2A R and MAO-A were evaluated using the western blot (with GAPDH as the loading control) (a). ELISA was used to measure intracellular and extracellular 5-HT levels (b); medium levels of TNF-α (h, left) and IL-1β (h, right). Representative lipid droplets determined by oil red O staining (40×) (c).TG levels (d, left) and protein levels of PKCε, CD36, GPAT1, Na + -K + -ATPase, and β-actin (d, right). Mitochondria and ROS distribution in the PA-treated cells determined by co-localization of mitochondria and ROS fluorescent dye staining (63×3×) (e). H 2 O 2 levels (f, left) and ROS distribution (fluorescent dye staining, 31.5×) (f, right). Whole-cell protein levels of phosphorylated (p-) IκBα, IκBα, p-NF-κB p65, NF-κB p65, and GAPDH in control (Ctrl), 5-HT and PA (alone or in combination)-treated cells (g, left), Ctrl, PA with or without CDP-treated cells (g, middle), and Ctrl, PA+5-HT-co-treated with or without CGL-treated cells (g, right). Data are presented as the mean±SD of at least four independent experiments. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01. Abbreviations: SH, sarpogrelate hydrochloride; CDP, carbidopa; CGL, clorgyline; CP, cytoplasm; PM, plasmalemma.

To observe the distribution of ROS in cells, we employed the DCFH-DA fluorescent probe, and MitoTracker®Red CMXRos was utilized to locate mitochondria. We found that ROS and mitochondria co-localized in PA-treated macrophages ( Fig.5, e ) , indicating that mitochondria are the sites of PA-induced ROS production. In addition, when macrophages were exposed to PA, 5-HT+PA, or treated with CDP or CGL together, the changes of intracellular H 2 O 2 and ROS levels were consistent ( Fig.5, f ) . Moreover, CDP significantly suppressed the production of H 2 O 2 induced by PA, while CGL strongly suppressed the production of H 2 O 2 induced by PA or 5-HT+PA ( Fig.5, f ) . The results indicated that the ROS mainly induced by PA was H 2 O 2 , which was caused by 5-HT degradation in mitochondria.

To examine the association between 5-HT degradation and macrophage inflammation, we analyzed the NF-κB p65 and IκBα expressions and their phosphorylation levels in cells as well as those of TNF-α and IL-1β in medium. The phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and IκBα was increased while IκBα expression was downregulated in macrophages exposed to 5-HT and PA. These effects were exacerbated by co-treatment with 5-HT and PA ( Fig.5, g left). CDP treatment could significantly suppress the PA effects ( Fig.5, g middle), and CGL treatment could dramatically suppress the effects of 5-HT and PA ( Fig.5, g right). At the same time, CDP and CGL treatment markedly inhibited the increase in TNF-α and IL-1β levels in PA-induced medium, and CGL treatment also significantly inhibited those induced by 5-HT+PA ( Fig.5, h ) . It is suggested that the activation of NF-κB and the release of inflammatory cytokines induced by PA are the result of 5-HT degradation and ROS production in mitochondria.

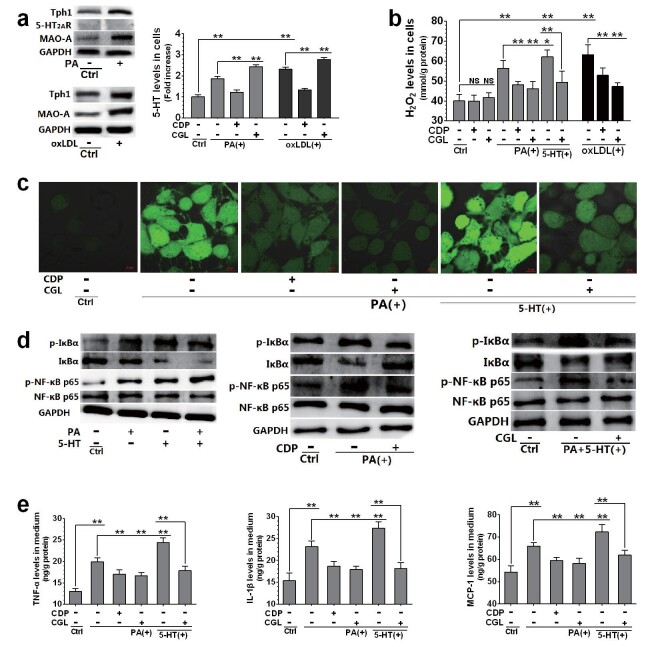

The Production of ROS and Inflammatory Cytokines in HUVECs Induced by PA and oxLDL also Depends on the Activation of 5-HT Degradation and 5-HT Synthesis

To elucidate the effect of the 5-HT system on vascular ECs, HUVECs cultured in vitro were exposed to PA or oxLDL and treated with or without CDP and CGL. Like in ApoE −/− mouse aortic ECs, we also detected the expression of Tph1 and MAO-A, but not that of 5-HT 2A R, in HUVECs ( Fig.6, a ) . In addition, HUVECs exposed to PA or oxLDL had increased expression of Tph1 and MAO-A and increased intracellular 5-HT levels ( Fig.6, a ) . However, the elevation of 5-HT levels by PA and oxLDL was significantly inhibited by CDP treatment and exacerbated by CGL treatment ( Fig.6, a ) . Furthermore, the increase in H 2 O 2 levels induced by PA or oxLDL was significantly suppressed by CDP and CGL, while that induced by a combination of 5-HT and PA was also significantly suppressed by CGL treatment ( Fig.6, b ) . These results indicate that lipid-induced 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT degradation lead to increased mitochondrial H 2 O 2 production in HUVECs.

Fig.6. Relationship between 5-HT system activation and PA or oxLDL-induced dysfunctions in HUVECs.

HUVECs were treated with CDP (30 µM), CGL (10 µM), PA (200 µM), oxLDL (150 µg/mL), and 5-HT (50 µM). The cells were pre-treated with each drug for 24 h, followed by PA and 5-HT treatment (alone or in combination) or oxLDL treatment for another 12 h. Whole-cell protein levels of Tph1, 5-HT 2A R, MAO-A, and GAPDH in control (Ctrl) and PA-treated cells (a, left up), and Tph1 and MAO-A in Ctrl and oxLDL-treated cells (a, left down), and intracellular and extracellular 5-HT levels in Ctrl, PA or oxLDL-treated, and CDP with PA or oxLDL-treated cells (a, right). H 2 O 2 levels in cells (b). ROS distribution (fluorescent dye staining, 63×) (c). Whole-cell protein levels of phosphorylated (p-) IκBα, IκBα, p-NF-κB p65, NF-κB p65, and GAPDH in Ctrl, 5-HT and PA (alone or in combination)-treated cells (d, left), Ctrl, PA with or without CDP-treated (d, middle) cells, and Ctrl, PA+5-HT-co-treated with or without CGL-treated cells (d, right). ELISA was used to measure medium levels of TNF-α (e, left) , IL-1β (e, middle), and MCP-1 (e, right). Data are presented as the mean±SD of at least four independent experiments. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01. Abbreviations: CDP, carbidopa; CGL, clorgyline.

In addition, the effects of PA and 5-HT on ROS content, NF-κB activation, and inflammatory cytokine release were analyzed in HUVECs. It was found that PA had comparable effects on ROS production and inflammation in macrophages and HUVECs. CDP and CGL treatment markedly inhibited ROS production in PA-treated HUVECs, while CGL also strongly inhibited ROS production induced by 5-HT and PA ( Fig.6, c ) . Accordingly, PA and 5-HT treatment (alone or in combination) led to increased phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and IκBα and downregulation of IκBα ( Fig.6, d , left); CDP significantly inhibited these PA effects ( Fig.6, d , left), while CGL significantly inhibited the combined effects of 5-HT and PA ( Fig.6, d , right). In addition, the increase in TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 levels in the medium of PA-treated HUVECs was strongly inhibited by CDP and CGL treatment, and the combined effect of 5-HT and PA was also significantly inhibited by CGL treatment ( Fig.6, e ) . Altogether, these results indicate that the increase in 5-HT synthesis and mitochondrial 5-HT degradation are also key factors underlying the lipid-induced activation of NF-κB and the release of inflammatory cytokines in vascular ECs.

Discussion

The relationship between the activation of peripheral 5-HT system and AS lesions has been previously reported. Researchers found that 5-HT contributes to vascular endothelial damage by participating in platelet aggregation, thrombus formation, and vasoconstriction 25 , 26) . 5-HT is also involved in VSMC proliferation during AS 27 , 28) , and stimulates the expression of tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in ECs 29) , monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium 30) , and macrophage foam cell formation associated with increased uptake of oxLDL 31) . Studies showed that 5-HT exerts its AS-associated effects by acting on 5-HT 2A R, and that treatment with the 5-HT 2A R antagonist sarpogrelate prevents AS-associated disorders such as vasospasm and microvascular constriction when atherosclerotic plaques rupture in an AS animal model 32 , 33) . In this study, we revealed that activation of the peripheral 5-HT system, including increased 5-HT synthesis, up-regulated 5-HT 2A R expression and increased 5-HT degradation, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AS. We confirmed that the increase of TG and VLDL synthesis and the decrease of HDL production were associated with the activation of the 5-HT system in liver in ApoE −/− mice fed HFD. This effect of 5-HT was related to dyslipidemia. The same pathological mechanism was noted in our previous studies on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 16) . Furthermore, we confirmed that macrophages infiltrating into the arterial intima and forming foam cells as well as activation of NF-κB and release of inflammatory cytokines in vascular ECs during AS plaque formation were also associated with the activation of the 5-HT system. By the combined inhibition of 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT 2A R, CDP and SH could strongly inhibit the development of AS. They not only inhibited hepatic steatosis and dyslipidemia but also directly acted on vascular ECs and macrophages, inhibiting macrophage recruitment by vascular ECs and macrophage foam cell formation. Although CDP could also reduce L-dopamine synthesis by inhibiting AADC, we did not detect changes in L-dopamine levels in the blood and liver of ApoE −/− mice fed HFD and treated with CDP or left untreated. Therefore, we inferred that L-dopamine is not related with the development of AS. In cultured THP-1 cell-derived macrophages, we confirmed that oxLDL and PA-induced formation of lipid droplets, involving the increase of both lipid uptake and TG synthesis, was due to 5-HT 2A R activation; both in cultured macrophages and in cultured HUVECs we demonstrated that lipid-induced increase of ROS production in cellular mitochondria and inflammatory cytokine release was due to the increase in both 5-HT synthesis and MAO-A-catalyzed 5-HT degradation.

We found that the combination of SH and CDP only mildly improved dyslipidemia in HFD-fed ApoE −/− mice ( Fig.2 ) , but strongly inhibited the formation of AS plaques in the aorta ( Fig.1 ) . Therefore, we believe that the key reason why SH and CDP inhibit AS was that they directly acted on macrophages and vascular ECs, preventing the formation of AS plaques by inhibiting the activity of 5-HT 2A R and synthesis of 5-HT, whereas improving dyslipidemia does not play an important role in suppressing the formation of AS. In addition, we found that the effects of SH and CDP were not associated with amelioration of IR in ApoE −/− mice 21) . IR might not be the key factor underlying AS.

Previously, we studied the mechanism of SFA-induced lipid synthesis and lipid-droplet formation in hepatocytes 16) . We confirmed that 5-HT 2A R was activated when hepatocytes were exposed to SFA, which mediated the generation of diacylglycerol catalyzed by phospholipase C; diacylglycerol combined with PKCε to activate PKCε; and activated PKCε mediated TG synthesis and lipid droplet accumulation in hepatocytes. In this study, we found that the molecular mechanism of oxLDL- and PA-induced macrophage foamization was similar to that of SFA-induced lipid droplet formation in hepatocytes 16) . PA and oxLDL could activate PKCε by activating the 5-HT 2A R of macrophages, leading to upregulation of the TG synthase GPAT1, increased TG synthesis, and increased oxLDL uptake associated to CD36 activation, finally resulting in accumulation of lipid droplets in cells. It is reported that CD36, a typical SR, has a high affinity to oxLDL, thereby performing its atherogenic role by internalization of the CD36–oxLDL binding 34) , which plays a key role in the formation of macrophage foam cells. In addition, we conjecture that vascular ECs (aortic ECs and HUVECs) may not express 5-HT 2A R.

Previously, we also demonstrated that in hepatocytes, the overproduction of ROS in mitochondria induced by SFAs was due to the increased degradation of 5-HT catalyzed by MAO-A, resulting in the activation of NF-κB and release of inflammatory cytokines 16) . This study showed that the mechanism of previously study also applied to macrophages and HUVECs exposed to oxLDL or PA, leading to the release of MCP-1 in HUVECs and release of TNF-α and IL-1β both in macrophages and in HUVECs. Madamanchi et al. 35) reported that in ApoE −/− mice, as AS worsened, mitochondrial ROS production increased; mitochondrial dysfunction with increased ROS production led to decreased aerobic capacity, a strong predictor of mortality, and caused endothelial dysfunction/apoptosis, VSMC proliferation/apoptosis, and macrophage apoptosis, thereby leading to the development of AS. Though it is accepted that nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, xanthine oxidase, mitochondrial enzymes, lipoxygenases, myeloperoxidases, and uncoupled endothelial NO synthase are the major ROS generators in the blood vessels 36) , this study indicated that the increase of 5-HT degradation induced by lipid is key to the increase of ROS production in macrophages and ECs.

We hypothesize that lipids such as oxLDL and SFAs (PA), control cellular lipid metabolism and ROS production in a similar way. These stimulators regulate the activation of PKC by activating 5-HT 2A R, thus inducing cellular lipid synthesis and uptake on the one hand, and mitochondrial ROS production by promoting 5-HT synthesis and MAO-A-catalyzed 5-HT degradation, leading to NF-κB activation and inflammatory cytokine release, on the other hand. Therefore, AS is probably due to lipid-induced activation of the 5-HT system in cells. In vascular ECs, activation of 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT degradation lead to the release of inflammatory cytokines, especially MCP-1, which recruit monocytes into the intima of blood vessels. In macrophages and hepatocytes, on the other hand, activation of 5-HT 2A R, 5-HT synthesis, and 5-HT degradation lead to the formation of macrophage foam cells, hepatic steatosis, and dyslipidemia. We believe that targeting the cellular 5-HT system is a potential therapeutic target for AS, and that it is necessary to inhibit both the 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT 2A R.

Acknowledgements and Notice of Grant Support

This study was supported by the Jiangsu Undergraduate Innovation Training Program Fund (No. 201610316155), “Double First-Class” University Project of China Pharmaceutical University (No. CPU2018GY23), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570720). The authors are grateful to Associate Professor Wenxia Bai (Jiangsu Center for Safety Evaluation of Drugs, China) for her contribution to the histopathological examinations, and Micro world Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) for contribution to immunohistochemical staining.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1).Hansson GK and Hermansson A: The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol, 2011; 12: 204-212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Peluso I, Morabito G, Urban L, Ioannone F and Serafini M: Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis development: the central role of LDL and oxidative burst. Endocr Metab Immune, 2012; 12: 351-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Ketelhuth DF and Hansson GK: Cellular immunity, low-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis: break of tolerance in the artery wall. Thromb Haemostasis, 2011; 106: 779-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN and Bobryshev YV: Endothelial Barrier and Its Abnormalities in Cardiovascular Disease. Front Physiol, 2015; 6: 365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ and Fisher EA: Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013; 13: 709-721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Murphy DL and Lesch KP: Targeting the murine serotonin transporter: insights into human neurobiology. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2008; 9: 85-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Hoyer D, Hannon JP and Martin GR: Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Be, 2002; 71: 533-554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Watanabe T and Koba S: Roles of Serotonin in Atherothrombosis and Related Diseases. In: Traditional and Novel Risk Factors in Atherothrombosis, ed by Gaxiola E, pp57-70, InTech Publisher, Rijeka, Croatia, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9).Hayashi T, Sumi D, Matsui-Hirai H, Fukatsu A, Arockia RPJ, Kano H, Tsunekawa T and Iguchi A: Sarpogrelate HCl, a selective 5-HT(2A) antagonist, retards the progression of atherosclerosis through a novel mechanism. Atherosclerosis, 2003; 168: 23-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Suguro T, Watanabe T, Kanome T, Kodate S, Hirano T, Miyazaki A and Adachi M: Serotonin acts as an up-regulator of acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase-1 in human monocyte-macrophages. Atherosclerosis, 2006; 186: 275-281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Sun YM, Su Y, Jin HB, Li J and Bi S: Sarpogrelate protects against high glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Int J Cardiol, 2011; 147: 383-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Fanburg BL and Lee SL: A new role for an old molecule: serotonin as a mitogen. Am J Physiol, 1997; 272: 795-806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Li T, Guo KK, Qu W, Han Y, Wang SS, Lin M, An SS, Li X, Ma SX, Wang TY, Ji SY, Hanson C and Fu JH: Important role of 5-hydroxytryptamine in glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance in liver and intraabdominal adipose tissue of rats. J Diabetes Invest, 2016; 7: 32-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Li X, Guo KK, Li T, Ma SX, An SS, Wang SS, Di J, He SY and Fu JH: 5-HT 2 receptor mediates high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis and very low density lipoprotein overproduction in rats. Obes Res Clin Pract, 2018; 12: 16-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Fu JH, Ma SX, Li X, An SS, Li T, Guo KK, Lin M, Qu W, Wang SS, Dong XY, Han XY, Fu T, Huang XP, Wang TY and He SY: Long-term Stress with Hyperglucocorticoidemia-induced Hepatic Steatosis with VLDL Overproduction Is Dependent on both 5-HT 2 Receptor and 5-HT Synthesis in Liver. Int J Biol Sci, 2016; 12: 219-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Fu JH, Li C, Zhang GL, Tong X, Zhang HW, Ding J, Ma YY, Cheng R, Hou SS, An SS, Li X and Ma SX: Crucial Roles of 5-HT and 5-HT2 Receptor in Diabetes-Related Lipid Accumulation and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Generation in Hepatocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2018; 48: 2409-2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Grandoch M, Feldmann K, Göthert JR, Dick LS, Homann S, Klatt C, Bayer JK, Waldheim JN, Rabausch B, Nagy N, Oberhuber A, Deenen R, Köhrer K, Lehr S, Homey B, Pfeffer K and Fischer JW: Deficiency in lymphotoxin β receptor protects from atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Circ Res, 2015; 116: 57-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Gao J, Song J, Du M and Mao X: Bovine α-Lactalbumin Hydrolysates (α-LAH) Ameliorate Adipose Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Fed C57BL/6J Mice. Nutrients, 2018; 10: 242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Prabhakar P, Reeta KH, Maulik SK and Dinda AK: Protective effect of thymoquinone against high-fructose diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Eur J Nutr, 2015; 54: 1117-1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Vedhachalam C, Duong PT, Nickel M, Nguyen D, Dhanasekaran P, Saito H, Rothblat GH, Katz SL and Phillips MC: Mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated cellular lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I and formation of high density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem, 2007; 282: 25123-25130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Bhatt P, Makwana D, Santani D and Goyal R: Comparative effectiveness of carvedilol and propranolol on glycemic control and insulin resistance associated with L-thyroxin-induced hyperthyroidism--an experimental study. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 2007; 85: 514-520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Zhang DX and Gutterman DD: Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol-Heart C, 2007; 292: H2023-H2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Kunjathoor VV, Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Moore KJ, Andersson L, Koehn S, Rhee JS, Silverstein R, Hoff HF and Freeman MW: Scavenger receptors class A-I/II and CD36 are the principal receptors responsible for the uptake of modified low density lipoprotein leading to lipid loading in macrophages. J Biol Chem, 2002; 277: 49982-49988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Gruben N, Shiri-Sverdlov R, Koonen DPY and Hofker MH: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A main driver of insulin resistance or a dangerous liaison? Bba-Mol Basis Dis, 2014; 1842: 2329-2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Satoh K, Yatomi Y and Ozaki Y: A new method for assessment of an anti-5HT(2A) agent, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, on platelet aggregation. J Thromb Haemost, 2010; 4: 479-481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Creager MA, Beckman JA and Loscalzo J: Vascular Medicine: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease 2nd Ed, Philadelphia, USA, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 27).Watanabe T, Pakala R, Koba S, Katagiri T and Benedict CR: Lysophosphatidylcholine and reactive oxygen species mediate the synergistic effect of mildly oxidized LDL with serotonin on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation, 2001; 103: 1440-1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Watanabe T, Pakala R, Katagiri T and Benedict CR: Lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal acts synergistically with serotonin in inducing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Atherosclerosis, 2001; 155: 37-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Kawano H, Tsuji H, Nishimura H, Kimura S, Yano S, Ukimura N, Kunieda Y, Yoshizumi M, Sugano T, Nakagawa K, Masuda H, Sawada S and Nakagawa M: Serotonin induces the expression of tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in cultured rat aortic endothelial cells. Blood, 2001; 97: 1697-1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Lorenowicz MJ, Gils JV, Boer MD, Hordijk PL and Fernandez-Borja M: Epac1-Rap1 signaling regulates monocyte adhesion and chemotaxis. J Leukocyte Biol, 2006; 80: 1542-1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Aviram M, Fuhrman B, Maor I and Brook GJ: Serotonin increases macrophage uptake of oxidized low density lipoprotein. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem, 1992; 30: 55-61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Sigal SL, Gellman J, Sarembock IJ, Laveau PJ, Chen QS, Cabin HS and Ezekowitz MD: Effects of serotonin-receptor blockade on angioplasty-induced vasospasm in an atherosclerotic rabbit model. Arterioscler Thromb, 1991; 11: 770-783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Taylor AJ, Bobik A, Berndt MC, Kannelakis P and Jennings G: Serotonin blockade protects against early microvascular constriction following atherosclerotic plaque rupture. Eur J Pharmacol, 2004; 486: 85-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Tarhda Z, Semlali O, Kettani A, Moussa A, Abumrad NA and Ibrahimi A: Three Dimensional Structure Prediction of Fatty Acid Binding Site on Human Transmembrane Receptor CD36. Bioinform Biol Insights, 2013; 7: 369-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Madamanchi NR and Runge MS: Mitochondrial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circ Res, 2007; 100: 460-473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Förstermann U, Xia N and Li H: Roles of Vascular Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res, 2017; 120: 713-735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]