Abstract

Avulsion fractures of the distal tibia resulting from anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament are known as Tillaux fractures. This injury is usually seen among adolescents as a Salter Harris type 3 epiphysiolisis in relation to bone weakness in distal tibia due to ephiphyseal closure. Regarding adult patients, this pattern of fracture become such an atypical one due to supposed failure of ligament previous to bone, avoiding avulsion. However, some cases have been described in recent decades.

The purpose of the present study is to present an adult Tillaux case and add an exhaustive review of literature regarding mechanism of injury, associated lesions, treatment, postoperative care and follow up.

Level of Evidence

Level V.

Keywords: Tillaux fracture, Avulsion fracture anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, Anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, Avulsion fractures of the distal tibia

Abbreviations: AITFL, Anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament

1. Introduction

Avulsion fractures of the anterolateral aspect of distal tibia (Chaput tubercle) can result from the pull of the anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) (Fig. 1) due to extreme supination external rotation of the ankle and can condition ankle balance due to its intraarticular position.1 In adults, usually, the AITFL fails before the avulsion, keeping the bone intact. However, some cases have been described overcoming this failure and occurring with an avulsion.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The most common symptoms are pain, swelling, tenderness, weight bearing inability and no deformity. In the literature, surgical treatment for Tillaux fracture has been considered for those fracture with a displacement greater than 2 mm since 1997.2 However, different surgical approaches have been proposed with no clear evidence of which one has to be considered as of election.

Fig. 1.

Tillaux fracture and anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament.

The purpose of the present study is to present an adult Tillaux fracture case and an exhaustive review of the existing literature regarding mechanism of injury, associated lesions, treatment, postoperative care and follow up.

2. Case report

A 37 year old female presented in emergency room with an injury to her left ankle while snowboarding. She had no previous relevant medical conditions.

Radiographs of the left ankle showed a Tillaux fracture (Fig. 2). Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a fragment displacement greater than 2 mm (Fig. 2). The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation using one 4 mm lag screw through an anterolateral approach, using Kirschner wires as joysticks to help reducing the fragment. During surgery, integrity of the AITFL was demonstrated (Fig. 3). Adequate reduction of the fragment was assessed by direct visualization and intraoperative imaging (Fig. 4). Postoperatively the ankle was immobilized with a below the knee cast, and weight bearing was not allowed for 3 weeks. At the third week, progressive mobilization of the ankle was allowed, as well as partial progressive weight bearing with a walker from 3 to 6 weeks postoperative. Full weight bearing with walker orthosis was achieved at 6 weeks, and the orthosis was removed completely at 8 weeks. Follow up controls continued until 12 months. At the final follow up visit, fracture union was evaluated by standing x-ray and by CT scan (Fig. 5). Ankle ability was assessed by the American Ortophaedic Food & Ankle Score (AOFAS) with an score at 3 months of 91/100, 95/100 at 6 months, and 98/100 at 12 months, showing excellent results with full range of motion. No other complications appeared at the end of the follow up.

Fig. 2.

Tillaux Fracture (A) Lateral X-ray; (B) PA X-ray; (C) and (D) CT scan.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative evidence of anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament conservation.

Fig. 4.

PA (A) and lateral (B) X-ray of intraoperative reduction.

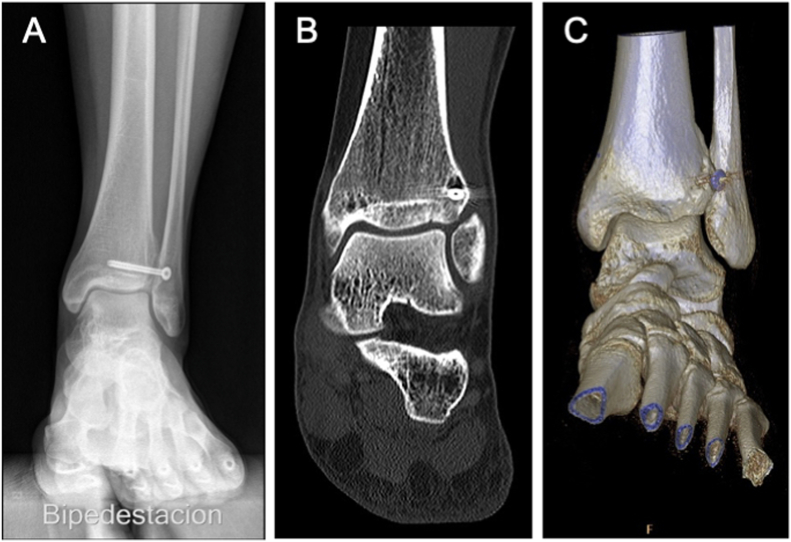

Fig. 5.

Tillaux Fracture consolidation evidence at 6 months follow-up on (A) (A) PA bipedestation X-ray; (B) CT scan; (C) 3D CT scan reconstruction.

3. Review of the recent literature

A Pubmed search of medical publications from 1997 to 2019 identified 12 studies (11 case reports and 1 retrospective study) regarding Tillaux fractures in adult patients. Studies with patients under 18 years old were excluded from our analysis. All cases reported are exposed in this review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previously reported cases of adult (>18yo) Tillaux fracture.

| Author | Year | No. | Age | Gen | Mechanism | Associated injury | Diagnostic CT scan | Treatment | Postoperative management | Screw (mm) | Fu | Outcome | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al.2 | 1997 | 1 | 58 | F | Fall from stairs | No | Yes | Arthroscopy + Open screw fixation | 1w splint +1w: Early motion |

2 (3.5 mm) | - | Successful | No |

| Patel et al.9 | 2006 | 1 | 19 | M | Fall from stairs | No | Yes | Open screw fixation | 6w: Below the knee cast 6-12w: Progressive wb +12w: Normal wb achieved |

1 (3.5 mm) | 3mo | Good | No |

| Chokkalingam et al.10 | 2012 | 2 | 60 | M | Fall from height | No | - | Open screw fixation | 6w: Below the knee cast 6-12w: Full wb allowed +12w: Normal wb achieved |

3 (−) | 19mo | Good | No |

| 27 | M | Road traffic accident | No | - | Open screw fixation | 1 (−) | 19mo | No | |||||

| Elmrini et al.11 | 2006 | 1 | 40 | M | Fall from height | No | Yes | Open screw fixation | 6w: Cast. Non wb | 2 (3.5 mm) | 12mo | Good | No |

| Amar et al.6 | 2009 | 2 | 30 | M | Fall from jump | No | Yes | Open screw fixation | 6w: Cast. Non wb | 2 (3.5 mm) | 22mo | Good | No |

| 25 | F | - | No | No | Conservative | 2w: Above the knee cast. 6w: Below the knee cast |

- | 2mo | Good | - | |||

| Torrent et al.5 | 2012 | 1 | 31 | F | Fall from height | Talar osteochondral lesion | Yes | Open screw fixation | 6w: Cast. Non wb 6-12w: Walker orthosis + Progressive wb +12w: Full wb |

3 (4 mm) | 18mo | AOFAS 84 Good |

No |

| Sharma et al.7 | 2013 | 1 | 31 | F | Ankle sprain | No | No | Conservative | 1w: Below the knee cast. Non wb 1-5w: Ankle brace orthosis. Non wb |

- | 1.5mo | - | - |

| Baker et al.14 | 2015 | 1 | 57 | F | Ankle sprain | No | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Oak et al.4 | 2014 | 2 | 47 | M | Ankle sprain | Syndesmotic disruption | Yes | Open screw fixation | 2w: Below the knee cast +2w: Removable cast boot |

2 transyndesmotic screws (−) + lateral plate | 11mo | Successful | No |

| 37 | F | Ankle sprain | No | Yes | Conservative | Initial: Cast Progressive: Removable cast boot |

- | 3mo | Successful | No | |||

| Kumar et al.12 | 2014 | 1 | 28 | M | Fall from height | No | Yes | Open screw fixation | 1w: Plaster splint 1w-8w: Progressive motion non wb 8w: Progressive wb +12w Full wb achieved |

2 (3.5 mm) | 14mo | Good | No |

| Kose et al.3 | 2016 | 2 | 36 | M | Ankle sprain | Avulsion fracture of PITFL | Yes | Open screw fixation | - | 1 | 14mo | AOFAS 100 Excellent |

No |

| 31 | M | Ankle sprain | Yes | Open screw fixation | 1w: Cast 1-4w: Progressive motion. Non wb +5w: Progressive wb |

1 | 6mo | AOFAS 100 Excellent |

No | ||||

| Mishra et al.13 | 2017 | 1 | 33 | M | Collision | No | Yes | Open screw fixation | 1w-6w: Progressive motion. Non wb 6w-10w: Progressive wb +10w Full wb |

1 (4 mm) | 12mo | FAAM 97 Excellent |

No |

| Feng et al.8 | 2018 | 17 | 18–55 | 10 M 7F |

11 Ankle sprain 6 Collision |

No | Unknown | Arthroscopic screw fixation | 1-6w: Early motion. Non wb +6w: Progressive wb |

1-2 (3 mm) | Mean 19mo |

AOFAS mean 91.7 |

No |

| Present study | 2019 | 1 | 37 | F | Fall during snowboarding | No | Yes | Open screw fixation | Cast 3 week 3-6w Progressive weight bearing 6-8w Full weight bearing (Walker) +8w Full weight bearing |

1 (4 mm) | 12 mo | AOFAS 91 (3mo) AOFAS 95 (6mo) AOFAS 98 (12mo) |

No |

F: Female/M: Male/fu: follow up/w: weeks/mo: months/wb: weight-bearing/PITFL: Posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament/Clinical outcomes expressed as asymptomatic, no pain, nor restriction without scoring assessment are considered as "Good".

Tillaux fracture pattern is atypical among adults (>18 years old). We found 34 Tillaux fracture cases reported in medical publications, 14 of which were female. Patient age at time of surgery ranged from 18 to 60 years old. The most common mechanism of injury was ankle sprain (50%, 17/34), while collision or traffic related injuries (24%, 8/34) and falls (24%, 8/34) were also described (1%, 1/34 unknown). After initial diagnostic X-ray, CT scan was performed in 88% (30/34) cases. Some cases (12%, 4/34) had been described with associated lesions such as avulsion fracture of posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (<1%, 2/34),3 syndesmotic disruption (<1%, 1/34)4 or talar osteochondral lesions (<1%,1/34).5

The treatment approach was mostly operative (91%, 31/34). However, 9% of the cases (3/34) were treated non-surgically due to a displacement lower than 2 mm (1/34 unknown). 2/4 coincide Among those surgically treated, 55% (17/31) were approached arthroscopically and 42% (13/31) with open reduction and internal fixation. Screw fixation was performed in all surgically treated cases with different number of screws: 1(55%, 17/31), 2 (42%, 12/31) and 3 (6%, 2/31). The size of the screws included a diameter range from 3 to 4 mm, being 3 mm the most commonly used (55%, 17/31). Oak et al.,4 described a Tillaux fracture associated with a syndesmotic disruption and a lateral plate was used with the 2 screws. Kose et al.3 and Torrent et al5 described Tillaux fracture related to avulsion fracture of posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament and osteochondral lesion, respectively, but they did not perform any modification to screw fixation treatment.

Postoperative immobilization time with a below the knee cast was widely variable for open reduction procedures, being used for 6 weeks postoperatively (38%, 5/13), 4 weeks (15%, 2/13), 3 weeks (8%, 1/13), 2 weeks (8%, 1/13), or 1week (15%, 2/13). Immobilization time was not reported in 23% of the cases (3/13). Postoperative progressive weight bearing was allowed at 6 weeks after the procedure in most cases (71%, 22/31), and full weight bearing without orthosis was allowed between 8 and 12 weeks after the surgery, in those cases which this timing was described (19%, 6/31). In the cases treated conservatively, immobilization with a cast was the standard (100%, 3/3) for 8 weeks (33%, 1/3)6 or for 1 week with a change to a walker orthosis for the next 5 weeks (33%, 1/3)7.

Follow up ranged between 3 and 22 months. 91% (31/34) of cases reported no complications, infections or unexpected outcomes, while 9% (3/34) failed to specifically report any complication. Functional results were reported to be good to excellent in all cases, however only 64% (22/34) were reported with clear score measurement with AOFAS (Table 1). For those patients following open reduction, final follow up functional score was available in 5/13, and reported an average AOFAS of 95.5 (84-100). For those following arthroscopically reduction, functional score was available in 17/17 and reported an average AOFAS of 91.7 (85-100). For those patients following non-operative management of Tillaux fractures no functional scores were reported at final follow up.

4. Discussion

Feng et al. in 20188 recommended ankle arthroscopy to treat Tillaux fractures using anterolateral and anteromedial approaches with 1 or 2 compression screws, reporting the following advantages in comparison to open surgery: low surgical trauma, closed reduction, no subperiosteal stripping, maintenance of normal blood supply, improved fracture healing, visualization of fracture displacement and cartilage injuries, clearance of cartilage fragments, precise reduction of fracture fragments and articular surface, shorter operative time, less bleeding, rapid postoperative recovery and lower infection risk.

However, as in our case, previous studies reporting open reduction, did not report evidence of complications or infection.2, 3, 4, 5, 6,9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Regarding X-ray assessment of articular alignment in closed reduction versus intraarticular direct surface assessment in open reduction, no evidences of poor functional mid-term outcomes have been reported.

Despite arthroscopic screw fixation appears to be an excellent treatment option and included the largest reported case-series describe by Feng et al.,8 in all remaining cases, the authors decline to ORIF over arthroscopy. These data could be explained because the use of arthroscopy in this type of fractures is still a technique that is not performed in all centers and that requires specific surgical skills. Also, as it is an infrequent injury without long case series, there are no comparative studies that can demonstrate superior clinical results with the use of arthroscopy.

In terms of implant choice, single 3 mm screw fixation is the most common surgical procedure, regardless of arthroscopic or open approach, without any reports of different results or complications among other surgical options that include 2 or 3 screws from 3 to 4 mm.

Postoperative management recommendations mostly included below the knee cast during 4–6 weeks5,6,9, 10, 11 allowing partial weight bearing at 6 weeks5,8, 9, 10,13 and full weight bearing at 10–12 weeks.5,9,10,12,13 The functional outcome of our case suggests that partial weight bearing with a walker could be tolerated from 3 weeks after the surgery, shorter than those 6 weeks that most previous studies recommend, and that full weight bearing can be achieved safely at 8 weeks, slightly before than those 10–12 weeks reported. This case could open the door to evaluate in the future the possibility to allow earlier weight bearing in selected young patients with a Tillaux fracture.

Functional results standardization in progressive postoperative course, with scales such as AOFAS, is essential to allow surgeons understand and compare among those surgical techniques or postoperative recommendations that are related to improved functional results.

Conservative treatment indications seem to be clear, including those Tillaux fractures with lower than 2 mm displacement. However, it seems an atypical choice (9%, 3/34),4,6,7 and two of them (67%, 2/3) did not underwent diagnostic CT scan and failed to report complications.6,7 Moreover, treatment option recommendations vary widely, with great disparity of treatment. ranging from 1 week of cast immobilization followed by walker, to above the knee cast6 for the first 3 weeks and then followed by a below the knee cast for the next 5 weeks.7

The lack of standard and the presence of a wide range of postoperative recommendations could be related to poor sample sizes of the previous reported cases, probably related to infrequent pathology.

5. Conclusion

Our review would like to encourage further studies reporting Tillaux fractures among adults and a comparison between open reduction and internal fixation and arthroscopic fixation, number of screws and size of those used in the surgical procedure, postoperative immobilization recommendations, weight bearing postoperative plan, and mid-term outcomes of fracture fixation, as well as recommendations and outcomes of conservatively treated Tillaux fractures.

Moreover, we would like to address the need to include detailed surgical approach, scoring functional results with standardized scoring methods and an extended follow up, as it must allow for real comparison between the results of different authors and techniques due to poor sample sizes.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The Author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

A. Millán-Billi, Email: amillan@santpau.cat.

M. Fa-Binefa, Email: mfa@santpau.cat.

M. Gómez-Masdeu, Email: mgomezma@santpau.cat.

I. Carrera, Email: icarrera@santpau.cat.

J. De Caso, Email: jcaso@santpau.cat.

References

- 1.Sawyer J.R., Spence D.D. Thirteenth. Elsevier Inc.; 2019. Fractures and Dislocations in. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller M.D. Arthroscopically assisted reduction and fixation of an adult Tillaux fracture of the ankle. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(1):117–119. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(97)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kose O., Yuksel H.Y., Guler F., Ege T. Isolated adult tillaux fracture associated with Volkmann fracture—a unique combination of injuries: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(5):1057–1062. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oak N.R., Sabb B.J., Kadakia A.R., Irwin T.A. Isolated adult tillaux fracture: a report of two cases. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53(4):489–492. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torrent Gómez J., Castillón Bernal P., Anglès Crespo F. Fractura de Tillaux del adulto: a propósito de un caso. Rev del Pie y Tobillo. 2012;26(2):43–46. doi: 10.1016/s1697-2198(16)30056-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amar M.F., Chbani B., Daoudi A., Elmrini A., Boutayeb F. La fracture de Tillaux chez l’adulte (à propos de deux cas) J Traumatol du Sport. 2009;26(1):32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jts.2009.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma B., Reddy I.S., Meanock C. The adult Tillaux fracture: one not to miss. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng S.M., Sun Q.Q., Wang A.G., Li C.K. All-inside” arthroscopic treatment of tillaux-chaput fractures: clinical experience and outcomes analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;57(1):56–59. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel A., Shur V. Juvenile Tillaux ankle fracture pattern in a skeletally mature adult. Foot. 2006;16(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2005.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chokkalingam S., Roy S., Chokkalingam S., et al. Adult tillaux fractures of ankle: case report. Internet J Orthop Surg. 2012;6(1):3–5. doi: 10.5580/27a7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmrini A., Marzouki A., Elibrahimi A., Mahfoud M., Elbardouni A., Elyaacoubi M. Fracture du Tubercule Tillaux chez un adulte de 40 ans. Med Chir du Pied. 2006;22(3):173–174. doi: 10.1007/s10243-006-0086-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar N., Prasad M. Tillaux fracture of the ankle in an adult: a rare injury. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53(6):757–758. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra P.K., Patidar V., Singh S.P. Chaput tubercle fracture in an adult-a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):RD01–RD02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/21567.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker J.F., et al. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(1):e31–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.086. 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]