Abstract

Eating disorders (EDs) are often stereotyped as affecting the SWAG, that is, as affecting mostly skinny, White, affluent girls. Over the last decade, however, significant progress has been made toward increasing diversity in ED research. There is consensus that EDs affect individuals of all genders, ages, sexual orientations, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds, with recent studies exploring social determinants of ED etiology, ED presentation, and developing diversity-affirming ED assessments. This article provides a brief summary of current developments related to diversity as a research theme, and proposes different perspectives toward further improving diversity in ED research. Specifically, we argue for exploring the role of diversity in ED treatment settings and outcomes, for pursuing diversity-oriented research pro-actively rather than as a reaction to issues of under-representation, and for integrating diversity across different areas of medical education and trainings in psychotherapy. Limitations with respect to the paucity of research, and the link between diversity as a research theme and ED-related workforce diversity are discussed.

Keywords: eating disorders, social diversity, gender bias, ethnic bias, sexual minority, medical education

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are of increasing public health concern (1). Characterized by body image concerns, abnormal eating, and weight-control behaviors (2), about 1.69% of the global population suffer from an ED such as Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, or Binge Eating Disorder during their lifetime (3, 4). EDs pose one of the highest mortality risks among mental disorders (5) and are associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes across multiple domains of functioning (6). Untreated ED-related healthcare and economic costs are substantial (7), emphasizing the importance of early detection and tailoring treatments toward ED patients' needs.

Counter to the widespread perception that EDs affect mostly White, adolescent girls from wealthy, industrialized countries (7, 8)—a stereotype colloquially labeled SWAG: skinny, White, affluent girls (9, 10)—epidemiological data show that individuals of all genders, sexual orientations, ages, ethnicities, and socio-economic status suffer from EDs (3, 4). In fact, recent years witnessed an unprecedented increase in ED incidence among men (11, 12), older adults (13, 14), gender and sexual minority individuals (15), underrepresented ethnic groups (16, 17), and adults with intellectual disabilities (18–20). Although wealthier individuals are more likely to receive ED treatment (9), the existing data suggest that EDs present equally across different socio-economic backgrounds (21). The changing demographics of the ED population point to a critical role of diversity in ED etiology, broadly defined in terms of any social or individual identity features that lead to the perception of differences between people (22), with possible implications for ED presentation and assessment, and the necessity for adjustments according to diverse treatment needs. At the same time, diversity issues such as gender, age, and ethnicity only recently rose to prominence as a subject of investigation in ED research.

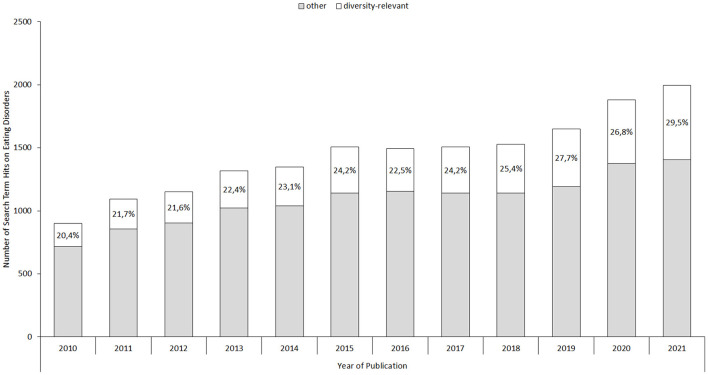

Figure 1 illustrates the diversity-related publication trend between 2010 and late 2021. Specifically, we queried PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) on November 11th, 2021, for studies published since 2010 on eating disorders (i.e., eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating, OSFED, or EDNOS), as mentioned in their title or abstract, which revealed 17,374 hits. In conjunction with diversity-related search terms (divers*, trans*, gay, lesbian, bisexual, ethnic, racial, minority, male, men, gender, elderly, older, and disability), a subgroup of 4,282 hits were identified. Stratified by publication year, the raw figures suggest up to a 1.5-times increase in the proportion of diversity-relevant among the total number of ED publications within the last decade (20.4 vs. 29.5%), with absolute publication numbers showing upwards of a three-fold increase (from 184 to 590 publications). These raw figures likely overestimate the number of publications specifically addressing diversity-issues in ED research due to the broadly defined search terms. Nevertheless, the increase in yearly search term hits shows an increase in referencing diversity-related themes, suggesting that diversity features are increasingly recognized in ED research.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the number of yearly total ED publications and potentially diversity-relevant ED publications. Percentages indicate the proportion of diversity-relevant among total yearly ED publications.

A potential reason for the historic inattention to diversity features in ED research and the need for its continued advancement is the lack of diversity among the ED research and professional communities. A recent survey attests that the global ED workforce is mainly comprised of White, cis-gendered women (23), with survey respondents recognizing high costs of education, limited social encouragement, and the lack of “leadership”—positions of power within the field are held mainly by White men (24–26)—as barriers to increasing workforce diversity. Improving workforce diversity will encourage individuals from underrepresented groups to seek treatment and promote patient-centered care, ultimately leading to the inclusion of their experiences and perspectives in the scientific discussion. Thus, as a caveat to further discussing the increasing interest in diversity-related themes, one may be wary that positive effects of this trend might be thwarted if left unaccompanied by overarching changes aiming at improving diversity representation among proponents of the field. At the same time, positive effects of improving workforce diversity could be undermined if solely relying on expecting diverse professionals to promote diversity in ED research (27). This suggests that independently discussing and advancing diversity as a research theme—as one of several levels of the field's diversity challenge—is warranted.

This article therefore presents a non-exhaustive summary of significant developments made with respect to investigating the role of diversity in ED etiology, presentation, and assessment. We present our perspective on advancing diversity as a research theme further, suggesting that future ED studies may focus on exploring the role of diversity in ED treatment settings and outcomes, anticipating diversity challenges, and investigating diversity perspectives across different areas of medical education and psychotherapeutic trainings.

Current Advances

Diversity as a Risk Factor in Eating Disorder Etiology

Higher rates of ED prevalence found among Asian-American men, Black women, transgender, and other sexual minority individuals compared to White, cis-gender women (15, 16, 28, 29) suggest that diversity-related features may be prominently associated to ED development. As a result, interest in understanding ED etiology as it links to diversity has increased. Two prominent models may be discussed that could link diversity to EDs: The socio-cultural model (30), which focusses on conformity with (sub-)cultural appearance ideals and peer-pressure as contributing factors to EDs, and the minority stress model (31), which posits that increased levels of stigma-related stress associated to being part of a social minority group would lead to higher burden of EDs. In a similar vein, the stress of adapting to appearance ideals of a majority group, i.e., acculturative stress, has been associated with increased ED symptoms in ethnic minority women (32). Convertino et al. (33) recently compared and integrated socio-cultural and stress models for addressing EDs in sexual minority individuals. Consistent with the models' central predictions, the authors reported that involvement within a sexual minority community increases appearance and body-ideal pressures, while stress-related experiences of heterosexist discrimination predict body-related dissatisfaction. However, it remains to be further empirically explored whether these findings can be generalized toward increased prevalence rates of EDs among ethnic minorities, in different age groups, or toward men, who represent a minority in the realm of EDs in contrast to other areas of clinical research (34). Nevertheless, these and similar findings highlight the complex ways in which group and gender identities may influence the development of EDs.

Burke et al. (35) recently advocated for extending diversity-related etiological models to account for interaction effects of occupying multiple diversity phenotypes in ED development. That is, the authors point to preliminary evidence showing that individuals with intersecting identities (e.g., ethnic and gender minority status) have an increased risk for EDs that is greater than the risk of each feature separately (36). Though the additional layer of complexity in investigating diversity in ED research poses methodological and sampling challenges (35), it also provides the narrative that focusing on single diversity-related features may create blind spots for recognizing certain (sub)groups with increased vulnerabilities.

Diversity in Eating Disorder Presentation

Significant progress has also been made toward identifying links between diversity and ED presentation. For example, men with EDs are often concerned with achieving a muscular, well-defined body ideal rather than thinness, which suggests different disordered eating patterns and weight-control behaviors compared to women (37–39), including anabolic steroid use associated with muscle dysmorphia (40) and different patterns in emotion regulation (41). Among transgender youth and adolescents with ED, suicidal ideations and suicide attempts are significantly elevated compared to cis-gender youth with EDs (42). Moreover, restricting feeding patterns in transgender youth may serve to delay the development of secondary sex characteristics and may thus additionally function to cope with gender-related distress (15). Finally, preliminary findings suggest that older individuals could be more adept at masking ED symptoms (43), although their symptoms may not fundamentally differ from younger populations (44).

It remains to be clarified whether and to what extend variations in ED presentation directly reflect diversity-related socio-cultural influences. The current evidence points toward the influence of gender and ethnic community norms on symptom reporting (45), differences in self-perception of symptom presence or severity (46), and help-seeking behavior (47). Final conclusions may be premature, as such variations in ED presentation may also reflect unequal access to treatment and health care services across diverse groups (48) or clinician bias (49). Others note that the specificity of diversity effects in ED presentation across diagnostic subgroups (e.g., Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder) needs further exploration, too (12). The need for diversity-affirming ED diagnostic criteria and assessments is nonetheless warranted.

Updates in Diagnostic Criteria

Updates in diagnostic criteria mirror an increased recognition of the role of diversity across the ED patient population (44). Specifically, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2) was the first to include Binge Eating Disorder as a specific diagnosis, which is an ED more commonly found in men (3), older individuals (50), and more prevalent in ethnic minority individuals (51). Amenorrhea was removed as a criterion for anorexia nervosa, which formerly excluded men, post-menopausal women as well as women receiving hormonal treatments (52). Although the discussion about the socio-cultural appropriateness of specific criteria continues (45), including the use of the body mass index as discriminating against Black and Asian individuals (53, 54), the existing updates in diagnostic criteria represent an important step toward equalizing treatment access irrespective of diverse backgrounds.

Further attention is directed toward the diversity-related appropriateness of screening and diagnostic tools, which several authors recognize were predominantly developed and validated among White women (39, 55). Recent diversity-affirming ED research, therefore, includes norming and reformulation efforts for standardized ED assessments such as the Eating Disorder Inventory and the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire for heterosexual men (56), gay men (57), transgender persons (58, 59), and Black patients (60). Although some of these efforts have revealed a convergence of questionnaire structures between diverse samples (61, 62), others have shown that identical questionnaires may measure dissimilar constructs in different diverse groups (63), emphasizing the necessity for validation across groups.

Perspectives for Future Diversity-Related ED Research

Identifying diversity-related risk factors, differences in ED presentation and the development of diversity-affirming diagnostic criteria and tools are vital to early detect EDs and address existing disparities in treatment access. At the same time, diversity as a research theme should not be limited to exploring its role in equalizing detection and treatment access but should be further extended to investigating the role of diversity in treatment settings (with potential inferences to treatment outcomes), anticipating future research challenges in ED treatment, and investigating diversity representation in professional education and training.

Diversity in Treatment Settings

Reports on treatment experiences of individuals from minority and/or marginalized groups indicate the need to improve diversity-related infrastructure and content in treatment settings. A prominent line of examples concerning diversity-related treatment experiences was recently summarized in a qualitative systematic review by our group (64). We reported that men with EDs face unique challenges during treatment, often struggling to feel understood by therapists (65), feeling unwanted in the treatment environment (66), experiencing marginalization in otherwise women-dominated facilities (67), or feeling that men-specific experiences and concerns are not taken into account (66). Similar reports among transgender youth and adolescents with EDs suggest that gender-related concerns are not or inadequately addressed during treatment (15, 29, 68, 69). One may suspect that the overrepresentation of White, cis-gender women in ED research may have inadvertently facilitated the development of treatment settings geared toward that population (70), again, displaying the need to tailor ED treatments according to the concerns and expectations of diverse groups. Rodgers et al. (16) summarize first instances of tailored ED treatments for individuals from underrepresented ethnic groups. For example, based on focus-group feedback, Shea et al. (71) suggest adaptations for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for EDs with Mexican-American women in terms of addressing cultural beliefs regarding ED etiology, social meanings of food and eating, and cultural preferences in help-seeking behavior. Similarly, Accurso et al. (72) recently published a protocol for adapting family-based treatment toward the needs of socio-economically disadvantaged and racially diverse adolescents. However, this avenue remains largely unexplored, as specific treatments targeting EDs in men, sexual minority individuals, or older adults are still lacking (70, 73, 74).

The impact of negative treatment experiences upon treatment outcomes in diverse groups is another area of needed research. Unlike in most other areas of clinical research (34), women constitute the majority in samples of randomized controlled trials that examine ED treatment efficacy, thus limiting conclusions about treatment outcomes in other groups. For illustrative purposes, we calculated the average sample composition of more than 300 studies summarized in the current German treatment guidelines (75), which recommend psychotherapy, primarily CBT, as first-choice intervention for adults with EDs. We found that women represented 90%, 95%, and more than 99% of total samples in studies on binge eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa, respectively. As the under-representation of diverse groups in outcome-related ED trials may have inadvertently facilitated the development of more effective treatments for cis-gender women, enhancing diversity representation in clinical ED trials is vital for ensuring optimal health care delivery and identifying areas in need of further improvement (76). First examples of gender-based comparisons suggest equality among treatment outcomes (77–81), but there is still a dearth of systematic investigations concerning gender and other diversity-related differences in outcome-related research.

Initial steps toward increasing diversity among ED trial populations may reside in identifying barriers to ED study participation. Using a mixture of reviews, field testing, and expert and patient interviews, Clark et al. (82) recently identified a lack of trust among patients from underrepresented groups as well as a lack of awareness of the importance of diversity among physicians and investigators as barriers to the execution of trials in diverse populations in general. Suggested solutions included involving patients in study design, offering adequate compensation, providing structured support to referring physicians, and training principal investigators, staff, and coordinators in cultural competency. Similar approaches could be used to both identify barriers to ED trial participation and develop ED-specific solutions as well.

Another key obstacle to advancing our understanding of the role of diversity in ED treatment settings and outcomes are reporting practices in clinical trials, which rarely address sample compositions beyond average age and sex or include diversity-oriented subgroup comparisons. Moreover, there is no consensus on how diversity and which aspects of it should be measured, rendering direct comparisons difficult. Therefore, we advocate for developing diversity-oriented reporting standards for clinical trials in ED research. As diversity issues may not be the focus of most future clinical ED trials, reporting standards could facilitate diversity-oriented systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Tools for guideline development are readily available (83), with initial examples demonstrating the feasibility of similar endeavors (84). Given the inevitably lower number of cases with the increasing complexity of subgroup comparisons, establishing reporting standards may also help to address methodological concerns related to the investigation of diversity effects (35, 85).

Anticipating Diversity Challenges

Differences in treatment access and outcomes represent a strong imperative for investigating existing inequalities associated with the affiliation to one or more diverse groups. To prevent further disparities, however, future research may also need to anticipate diversity challenges based on current developments, supporting the transition from a problem-focused toward an opportunity-focused approach (35). For example, we would argue that socio-economic and educational diversity will become increasingly relevant in ED etiology and treatment. Although at present there are no clear links between diversity in terms of socio-economic background and the prevalence of EDs (21), level of education, and other factors associated with socio-economic status have been linked to food insecurity during the Covid-19 pandemic (86). Food insecurity, in turn, has been repeatedly linked to ED pathology (87), suggesting that future ED populations may disproportionally stem from lower-income and lower-education households. Indeed, although affected at similar rates, past research suggests that individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds show increased health impairments due to EDs (88). Thus, it may be necessary to adjust treatment approaches toward anticipating differences in literacy and other education-related aspects of the patients and provide patients from less privileged backgrounds with additional access options to disorder-specific treatments. Although these implications are not entirely different from those proposed for adjusting psychotherapy for patients with intellectual disabilities (89) or for an aging patient population (90, 91) -which is another challenge ED research might soon face -the effort of their implementation will likely outweigh the social and economic costs of additional social disparities in ED treatment.

Admittedly, systematic projections about future diversity challenges in ED research remain limited by contemporary diversity conceptualizations, which distinguish within the aspects of ED etiology, presentation, and treatment access and outcomes by categorizing individuals based on sex, gender, age, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. Not only is it questionable whether these categories are representative of ED populations on a global scale (3), but grouping EDs based on social categories inevitably incurs the risk of an ecological fallacy, i.e., of inferring individual-level causation from group-level correlation. In other words, uncertainty remains about the causal mechanism(s) linking diversity to ED treatment challenges, as only a limited number of universal approaches, such as the minority stress model (31), have yet been proposed. Therefore, anticipating diversity challenges may require further research on individual-level factors linking diversity to ED outcomes and experiences.

Diversity in ED-Related Clinical Education

The diverse treatment needs of individuals with EDs are challenging to address without incorporating diversity aspects in clinical trainings (physicians, psychologists, psychotherapists). Numerous examples provide evidence for a lack of awareness regarding diversity issues among medical personnel, such that individuals of sexual minorities report a lack of trust in disclosing their sexual preferences (92, 93). Likewise, medical professionals report uncertainty in dealing with diversity issues (71) and feel that these issues were not adequately addressed as part of their education or training (94). Based on these and similar findings, there have been numerous calls to systematically incorporate diversity-related perspectives in medical education (95–97), including the representation of diversity in medical textbooks (98).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no diversity-oriented medical trainings that focus specifically on ED interventions or training. Some contemporary examples of diversity-oriented medical trainings have been evaluated at mostly North-American universities and institutions, although there are only a few examples of extensive curricula (99, 100). Furthermore, diversity trainings of the kind are often offered separately from general education, usually geared toward specific minority groups, and offered voluntarily, thus bearing the risk that only a limited number of students (e.g., those with prior knowledge and interest in the subject, and the willingness to question their positions) will participate. The voluntary nature of these classes could reinforce the perception of diversity issues as an afterthought rather than an essential component in medical education, which, in turn, may potentially affect the provision of care to patients.

While existing training may serve as a template for developing diversity-oriented ED curricula, a holistic approach sensitizing for diversity throughout professional education and training may be preferable. Such an approach not only requires building an extensive, evidence-based knowledge base on the critical role of diversity in ED presentation and treatment but may involve engaging, sensitizing, motivating, and diversifying both student bodies, teaching staff, and faculty administrations.

Discussion

Similar to how “swag” lost its popularity as a decade-old teenage slang, the acronym has become decreasingly less relevant for describing patient populations in ED research. There have been numerous advances toward understanding the role of diversity in ED etiology and ED presentation, with updated diagnostic criteria and the development of diversity-affirming diagnostic tools to target the existing disparities in treatment access.

Complementing existing efforts, we proposed that future ED research would need to focus on addressing the role of diversity in treatment experiences and disparities in outcomes, which may require adjusting recruitment, assessment, and reporting practices in clinical trials. Moreover, anticipating future developments that could pose diversity challenges and incorporating diversity-related issues systematically in ED-related clinical training are asked for, though tackling these issues may require considerable effort to extend theoretical conceptualizations of diversity and develop interventional approaches.

Of course, our perspective is itself limited by the general paucity of evidence, a majority of which originates from US-American and European contexts and authors, with research participants often recruited from populations that already have access to (private) healthcare treatment. Therefore, it would seem appropriate to also incorporate diverse, i.e., global research perspectives into the study of ED diversity, as well as perspectives of currently underserved groups.

As alluded to in the introduction, the potential benefits of advancing ED diversity as a research theme further depend upon improving workforce diversity. For example, study participation could be hindered if patients feel unwelcomed in research environments due to low diversity representation. Similarly, incorporating diversity within medical trainings could be ineffective at best and hypocritical at worst without addressing access barriers to medical education and training for individuals from underrepresented backgrounds. Advancing ED diversity thus remains a multi-level challenge that is aided but not solved by increasing research diversity.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

GP and GH conceived the topic and proposition of this manuscript. GH wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

We acknowledged the support by DFG Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Treasure J, Duarte TA, Schmidt U. Eating disorders. Lancet. (2020) 395:899–911. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC:? American Psychiatric Publishing; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qian J, Wu Y, Liu F, Zhu Y, Jin H, Zhang H, et al. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. (2021) 1–14. 10.1007/s40519-021-01162-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santomauro DF, Melen S, Mitchison D, Vos T, Whiteford H, Ferrari AJ. The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:320–328. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00040-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. (2014) 13:153–60. 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Udo T, Grilo CM. Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. (2019) 52:42–50. 10.1002/eat.23004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas V, Balas B, Gordon K. Facial femininity and perceptions of eating disorders: a reverse-correlation study. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0255766. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon KH, Perez M, Joiner TE. The impact of racial stereotypes on eating disorder recognition. Int J Eat Disord. (2002) 32:219–224. 10.1002/eat.10070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonneville KR, Lipson SK. Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students. Int J Eat Disord. (2018) 51:518–26. 10.1002/eat.22846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pike KM, Dunne PE, Addai E. Expanding the boundaries: reconfiguring the demographics of the “typical” eating disordered patient. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2013) 15:1–8. 10.1007/s11920-013-0411-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madden S, Morris A, Zurynski YA, Kohn M, Elliot EJ. Burden of eating disorders in 5–13-year-old children in Australia. Med J Aust. (2009) 190:410–4. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sangha S, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, McCuaig F. Eating disorders in males: how primary care providers can improve recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Mens Health. (2019) 13:1–12. 10.1177/1557988319857424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangweth-Matzek B, Kummer KK, Pope HG. Eating disorder symptoms in middle-aged and older men. Int J Eat Disord. (2016) 49:953–7. 10.1002/eat.22550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangweth-Matzek B, Hoek HW, Pope HG. Pathological eating and body dissatisfaction in middle-aged and older women. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2014) 27:431–5. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coelho JS, Suen J, Clark BA, Marshall SK, Geller J, Lam PY. Eating disorder diagnoses and symptom presentation in transgender youth: a scoping review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:1–10. 10.1007/s11920-019-1097-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodgers RF, Berry R, Franko DL. Eating disorders in ethnic minorities: an update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2018) 20:1–11. 10.1007/s11920-018-0938-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng ZH, Perko VL, Fuller-Marashi L, Gau JM, Stice E. Ethnic differences in eating disorder prevalence, risk factors, and predictive effects of risk factors among young women. Eat Behav. (2019) 32:23–30. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravestock S. Eating disorders in adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. (2000) 44:625–37. 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hove O. Prevalence of eating disorders in adults with mental retardation living in the community. Am J Ment Retard. (2004) 109:501–06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westwood H, Tchanturia K. Autism spectrum disorder in anorexia nervosa: an updated literature review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:41. 10.1007/s11920-017-0791-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huryk KM, Drury CR, Loeb KL. Diseases of affluence? A systematic review of the literature on socioeconomic diversity in eating disorders. Eat Behav. (2021) 43:101548. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberge MÉ, van Dick R. Recognizing the benefits of diversity: when and how does diversity increase group performance? Hum Resour Manag Rev. (2010) 20:295–308. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennings Mathis K, Anaya C, Rambur B, Bodell LP, Graham AK, Forney KJ, et al. Workforce diversity in eating disorders: a multi-methods study. West J Nurs Res. (2020) 42:1068–77. 10.1177/0193945920912396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wingard D, Trejo JA, Gudea M, Goodman S, Reznik V. Faculty equity, diversity, culture and climate change in academic medicine: a longitudinal study. J Natl Med Assoc. (2019) 111:46–53. 10.1016/j.jnma.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filardo G, Graca B Da, Sass DM, Pollock BD, Smith EB, Martinez MAM. Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: observational study (1994-2014). BMJ. (2016) 352:1–8. 10.1136/bmj.i847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinho-Gomes AC, Vassallo A, Thompson K, Womersley K, Norton R, Woodward M. Representation of women among editors in chief of leading medical journals. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:2123026. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.23026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laver KE, Prichard IJ, Cations M, Osenk I, Govin K, Coveney JD. A systematic review of interventions to support the careers of women in academic medicine and other disciplines. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:20380. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goode RW, Cowell MM, Mazzeo SE, Cooper-Lewter C, Forte A, Olayia OI, et al. Binge eating and binge-eating disorder in black women: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:491–507. 10.1002/eat.23217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagata JM, Ganson KT, Austin SB. Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2020) 33:562–7. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hazzard VM, Schaefer LM, Schaumberg K, Bardone-Cone AM, Frederick DA, Klump KL, et al. Testing the tripartite influence model among heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women. Body Image. (2019) 30:145–9. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. (2003) 129:674–97. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroon Van Diest AM, Tartakovsky M, Stachon C, Pettit JW, Perez M. The relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms: is it unique from general life stress? J Behav Med. (2014) 37:445–57. 10.1007/s10865-013-9498-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Convertino AD, Helm JL, Pennesi JL, Gonzales M, Blashill AJ. Integrating minority stress theory and the tripartite influence model: a model of eating disordered behavior in sexual minority young adults. Appetite. (2021) 163:105204. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman S, Ammar W, Lo K, Trepman E, Van Zuylen M, Etzioni O. Quantifying sex bias in clinical studies at scale with automated data extraction. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e196700. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke NL, Schaefer LM, Hazzard VM, Rodgers RF. Where identities converge: the importance of intersectionality in eating disorders research. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1605–9. 10.1002/eat.23371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beccia AL, Baek J, Jesdale WM, Austin SB, Forrester S, Curtin C, et al. Risk of disordered eating at the intersection of gender and racial/ethnic identity among U.S. high school students. Eat Behav. (2019) 34:101299. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagata JM, Ganson KT, Murray SB. Eating disorders in adolescent boys and young men: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2020) 32:476–81. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Núñez-Navarro A, Agüera Z, Krug I, Jiménez-Murcia S, Sánchez I, Araguz N, et al. Do men with eating disorders differ from women in clinics, psychopathology and personality? Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2012) 20:23–31. 10.1002/erv.1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S, Calzo JP, Brown TA, Mitchison D, et al. The enigma of male eating disorders: a critical review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 57:1–11. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badenes-Ribera L, Rubio-Aparicio M, Sánchez-Meca J, Fabris MA, Longobardi C. The association between muscle dysmorphia and eating disorder symptomatology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:351–71. 10.1556/2006.8.2019.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agüera Z, Paslakis G, Munguía L, Sánchez I, Granero R, Sánchez-González J, et al. Gender-related patterns of emotion regulation among patients with eating disorders. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:161. 10.3390/jcm8020161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duffy ME, Henkel KE, Joiner TE. Prevalence of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in transgender individuals with eating disorders: a national study. J Adolesc Heal. (2019) 64:461–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zayed M, Garry JP. Geriatric anorexia nervosa. J Am Board Fam Med. (2017) 30:666–9. 10.3122/jabfm.2017.05.170182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulchandani M, Shetty N, Conrad A, Muir P, Mah B. Treatment of eating disorders in older people: a systematic review. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:275. 10.1186/s13643-021-01823-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee-Winn A, Mendelson T, Mojtabai R. Racial/ethnic disparities in binge eating: disorder prevalence, symptom presentation, and help-seeking among Asian Americans and non-Latino Whites. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:1263–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacCaughelty C, Wagner R, Rufino K. Does being overweight or male increase a patient's risk of not being referred for an eating disorder consult? Int J Eat Disord. (2016) 49:963–6. 10.1002/eat.22556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffiths S, Mond JM, Li Z, Gunatilake S, Murray SB, Sheffield J, et al. Self-stigma of seeking treatment and being male predict an increased likelihood of having an undiagnosed eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. (2015) 48:775–8. 10.1002/eat.22413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. (2019) 40:105–25. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker AE, Franko DL, Speck A, Herzog DB. Ethnicity and differential access to care for eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. (2003) 33:205–12. 10.1002/eat.10129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smink FRE, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2012) 14:406–14. 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lydecker JA, Grilo CM. Different yet similar: examining race and ethnicity in treatment-seeking adults with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2016) 84:88–94. 10.1037/ccp0000048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Attia E, Roberto CA. Should amenorrhea be a diagnostic criterion for anorexia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord. (2009) 42:581–9. 10.1002/eat.20720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. J Am Med Assoc. (2003) 289:187–93. 10.1001/jama.289.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hood K, Ashcraft J, Watts K, Hong S, Choi W, Heymsfield SB, et al. Allometric scaling of weight to height and resulting body mass index thresholds in two Asian populations. Nutr Diabetes. (2019) 9:1–7. 10.1038/s41387-018-0068-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franko DL. Race, ethnicity, and eating disorders: considerations for DSM-V. Int J Eat Disord. (2007) 40:S31–4. 10.1002/eat.20455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith KE, Mason TB, Murray SB, Griffiths S, Leonard RC, Wetterneck CT, et al. Male clinical norms and sex differences on the eating disorder inventory (EDI) and eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord. (2017) 50:769–75. 10.1002/eat.22716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagata JM, Capriotti MR, Murray SB, Compte EJ, Griffiths S, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Community norms for the eating disorder examination questionnaire among cisgender gay men. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:92–101. 10.1002/erv.2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duffy ME, Calzo JP, Lopez E, Silverstein S, Joiner TE, Gordon AR. Measurement and construct validity of the eating disorder examination questionnaire short form in a transgender and gender diverse community sample. Psychol Assess. (2021) 33:459–63. 10.1037/pas0000996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagata JM, Murray SB, Compte EJ, Pak EH, Schauer R, Flentje A, et al. Community norms for the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) among transgender men and women. Eat Behav. (2020) 37:101381. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lydecker JA, White MA, Grilo CM. Black patients with binge-eating disorder: comparison of different assessment methods. Psychol Assess. (2016) 28:1319–24. 10.1037/pas0000246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Belon KE, McLaughlin EA, Smith JE, Bryan AD, Witkiewitz K, Lash DN, et al. Testing the measurement invariance of the eating disorder inventory in nonclinical samples of Hispanic and Caucasian Women. Int J Eat Disord. (2015) 48:262–70. 10.1002/eat.22286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Serier KN, Peterson KP, VanderJagt H, Sebastian RM, Mullins CR, Medici J, et al. Factor analytic support for the EDE-Q7 among American Indian/Alaska Native undergraduate women. Eat Weight Disord. (2021) 10.1007/s40519-021-01335-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spivak-Lavi Z, Peleg O, Tzischinsky O, Stein D, Latzer Y. Differences in the factor structure of the eating attitude test-26 (Eat-26) in different cultures in Israel: Jews, muslims, and christians. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1899. 10.3390/nu13061899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richardson C, Paslakis G. Men's experiences of eating disorder treatment: a qualitative systematic review of men-only studies. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 28:237–50. 10.1111/jpm.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thapliyal P, Conti J, Bandara RSL, Hay P. “It exists”: an exploratory study of treatment experiences in men with eating disorders. Aust Psychol. (2020) 55:534–45. 10.1111/ap.12455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson KJ, Mountford VA, Sperlinger DJ. Being men with eating disorders: perspectives of male eating disorder service-users. J Health Psychol. (2013) 18:176–86. 10.1177/1359105312440298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kinnaird E, Norton C, Pimblett C, Stewart C, Tchanturia K. “There's nothing there for guys”. Do men with eating disorders want treatment adaptations? A qualitative study. Eat Weight Disord. (2019) 24:845–52. 10.1007/s40519-019-00770-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hartman-Munick SM, Silverstein S, Guss CE, Lopez E, Calzo JP, Gordon AR. Eating disorder screening and treatment experiences in transgender and gender diverse young adults. Eat Behav. (2021) 41:101517. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thapliyal P, Hay P, Conti J. Role of gender in the treatment experiences of people with an eating disorder: a metasynthesis. J Eat Disord. (2018) 6:18. 10.1186/s40337-018-0207-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lavender JM, Brown TA, Murray SB. Men, muscles, and eating disorders: an overview of traditional and muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:32. 10.1007/s11920-017-0787-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shea M, Cachelin F, Uribe L, Striegel RH, Thompson D, Wilson GT. Cultural adaptation of a cognitive behavior therapy guided self-help program for Mexican American women with binge eating disorders. J Couns Dev. (2012) 90:308–18. 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00039.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Accurso EC, Mu KJ, Landsverk J, Guydish J. Adaptation to family-based treatment for Medicaid-insured youth with anorexia nervosa in publicly-funded settings: protocol for a mixed methods implementation scale-out pilot study. J Eat Disord. (2021) 9:99. 10.1186/s40337-021-00454-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldhammer HB, Maston ED, Keuroghlian AS. Addressing eating disorders and body dissatisfaction in sexual and gender minority youth. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 56:318–22. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mangweth-Matzek B, Hoek HW. Epidemiology and treatment of eating disorders in men and women of middle and older age. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2017) 30:446–51. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herpertz S, Fichter M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B, Vocks S, et al. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Behandlung der Essstörungen. Berlin: Springer; (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gray DM, Nolan TS, Gregory J, Joseph JJ. Diversity in clinical trials: an opportunity and imperative for community engagement. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 6:605–7. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00228-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Strobel C, Quadflieg N, Naab S, Voderholzer U, Fichter MM. Long-term outcomes in treated males with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa—A prospective, gender-matched study. Int J Eat Disord. (2019) 52:1353–64. 10.1002/eat.23151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lydecker JA, Gueorguieva R, Masheb R, White MA, Grilo CM. Examining sex as a predictor and moderator of treatment outcomes for binge-eating disorder: analysis of aggregated randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:20–30. 10.1002/eat.23167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fernández-Aranda F, Krug I, Jiménez-Murcia S, Granero R, Núñez A, Penelo E, et al. Male eating disorders and therapy: a controlled pilot study with one year follow-up. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2009) 40:479–86. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coelho JS, Suen J, Marshall S, Burns A, Geller J, Lam PY. Gender differences in symptom presentation and treatment outcome in children and youths with eating disorders. J Eat Disord. (2021) 9:113. 10.1186/s40337-021-00468-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Murray MF, Cox SA, Henretty JR, Haedt-Matt AA. Women of diverse sexual identities admit to eating disorder treatment with differential symptom severity but achieve similar clinical outcomes. Int J Eat Disord. (2021) 54:1652–62. 10.1002/eat.23576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clark LT, Watkins L, Piña IL, Elmer M, Akinboboye O, Gorham M, et al. Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2019) 44:148–72. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR network. BMC Med. (2010) 8:24. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heidari S, Babor TF, De Castro P, Tort S, Curno M. Sex and gender equity in research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev. (2016) 1:2. 10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodgers RF, Donovan E, Cousineau TM, McGowan K, Yates K, Cook E, et al. Ethnic and racial diversity in eating disorder prevention trials. Eat Disord. (2019) 27:168–82. 10.1080/10640266.2019.1591824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paslakis G, Dimitropoulos G, Katzman DK. A call to action to address COVID-19-induced global food insecurity to prevent hunger, malnutrition, and eating pathology. Nutr Rev. (2021) 79:114–6. 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hazzard VM, Loth KA, Hooper L, Becker CB. Food insecurity and eating disorders: a review of emerging evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2020) 22:1–9. 10.1007/s11920-020-01200-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mitchison D, Hay P, Slewa-Younan S, Mond J. The changing demographic profile of eating disorder behaviors in the community. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:943. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Surley L, Dagnan D. A review of the frequency and nature of adaptations to cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with Intellectual Disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2019) 32:219–237. 10.1111/jar.12534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laidlaw K, Pachana NA. Aging, mental health, and demographic change: challenges for psychotherapists. Prof Psychol Res Pract. (2009) 40:601–8. 10.1037/a0017215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Groenewald E, Joska J, Araya R. Psychotherapy adaptation in aging populations. In: Global Mental Health and Psychotherapy: Adapting Psychotherapy for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. London: Elsevier. p. 321–40. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Burkhart Q, Abel GA, Lyratzopoulos G, Beckett MK, et al. Sexual minorities in england have poorer health and worse health care experiences: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:9–16. 10.1007/s11606-014-2905-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes . Einstellungen gegenüber Lesben, Schwulen und Bisexuellen in Deutschland. (2017). Available online at: https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/Umfragen/umfrage_einstellungen_geg_lesb_schwulen_und_bisex_menschen_de.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

- 94.Turner D, Driemeyer W, Nieder TO, Scherbaum N, Briken P. Wie viel sex braucht das studium der medizin?-Eine Erhebung des Wissens und Interesses Medizinstudierender zum Thema Sexualmedizin. PPmP Psychother Psychosom Medizinische Psychol. (2014) 64:452–7. 10.1055/s-0034-1389961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maduakolam E, Madden B, Kelley T, Cianciolo AT. Beyond diversity: envisioning inclusion in medical education research and practice. Teach Learn Med. (2020) 32:459–65. 10.1080/10401334.2020.1836462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Diaz T, Navarro JR, Chen EH. An institutional approach to fostering inclusion and addressing racial bias: implications for diversity in academic medicine. Teach Learn Med. (2020) 32:110–6. 10.1080/10401334.2019.1670665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ludwig S, Gruber C, Ehlers JP, Ramspott S. Diversity in medical education. GMS J Med Educ. (2020) 37:1–6. 10.3205/zma001320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kalantari A, Alvarez A, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Nwabueze A, Cooney R, et al. 228 sex and racial visual representation in emergency medicine textbooks: a call to action to dismantle the hidden curriculum against diversity in medicine. Ann Emerg Med. (2021) 78:S92. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.09.240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gibson AW, Gobillot TA, Wang K, Conley E, Coard W, Matsumoto K, et al. A novel curriculum for medical student training in LGBTQ healthcare : a regional pathway experience. J Med Educ Curric Dev. (2020) 7:1–7. 10.1177/2382120520965254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hawala-Druy S, Hill MH. Interdisciplinary: cultural competency and culturally congruent education for millennials in health professions. Nurse Educ Today. (2012) 32:772–8. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.