Abstract

Background

Integrative reviews within healthcare promote a holistic understanding of the research topic. Structure and a comprehensive approach within reviews are important to ensure the reliability in their findings.

Aim

This paper aims to provide a framework for novice nursing researchers undertaking integrative reviews.

Discussion

Established methods to form a research question, search literature, extract data, critically appraise extracted data and analyse review findings are discussed and exemplified using the authors’ own review as a comprehensive and reliable approach for the novice nursing researcher undertaking an integrative literature review.

Conclusion

Providing a comprehensive audit trail that details how an integrative literature review has been conducted increases and ensures the results are reproducible. The use of established tools to structure the various components of an integrative review increases robustness and readers’ confidence in the review findings.

Implications for practice

Novice nursing researchers may increase the reliability of their results by employing a framework to guide them through the process of conducting an integrative review.

Keywords: integrative literature review, methodology research, nursing, research design

Background

A literature review is a critical analysis of published research literature based on a specified topic (Pluye et al., 2016). Literature reviews identify literature then examine its strengths and weaknesses to determine gaps in knowledge (Pluye et al. 2016). Literature reviews are an integral aspect of research projects; indeed, many reviews constitute a publication in themselves (Snyder, 2019). There are various types of literature reviews based largely on the type of literature sourced (Cronin et al. 2008). These include systematic literature reviews, traditional, narrative and integrative literature reviews (Snyder, 2019). Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) found more than 35 commonly used terms to describe literature reviews. Within healthcare, systematic literature reviews initially gained traction and widespread support because of their reproducibility and focus on arriving at evidence-based conclusions that could influence practice and policy development (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). Yet, it became apparent that healthcare-related treatment options needed to review broader spectrums of research for treatment options to be considered comprehensive, holistic and patient orientated (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). Stern et al. (2014) suggest that despite the focus in healthcare on quantitative research not all pertinent questions surrounding the provision of care can be answered from this approach. To devise solutions to multidimensional problems, all forms of trustworthy evidence need to be considered (Stern et al. 2014).

Integrative reviews assimilate research data from various research designs to reach conclusions that are comprehensive and reliable (Soares et al. 2014). For example, an integrative review considers both qualitative and quantitative research to reach its conclusions. This approach promotes the development of a comprehensive understanding of the topic from a synthesis of all forms of available evidence (Russell, 2005; Torraco, 2005). The strengths of an integrative review include its capacity to analyse research literature, evaluate the quality of the evidence, identify knowledge gaps, amalgamate research from various research designs, generate research questions and develop theoretical frameworks (Russell, 2005). Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) suggested that integrative reviews exhibit similar characteristics to systematic reviews and may therefore be regarded as rigorous.

Integrative reviews value both qualitative and quantitative research which are built upon differing epistemological paradigms. Both types of research are vital in developing the evidence base that guides healthcare provision (Leppäkoski and Paavilainen, 2012). Therefore, integrative reviews may influence policy development as their conclusions have considered a broad range of appropriate literature (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005). An integrative approach to evidence synthesis allows healthcare professionals to make better use of all available evidence and apply it to the clinical practice environment (Souza et al. 2010). For example, Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) found in excess of 12 different types of reviews employed to guide healthcare practice. The healthcare profession requires both quantitative and qualitative forms of research to establish the robust evidence base that enables the provision of evidence-based patient-orientated healthcare.

Integrative reviews require a specific set of skills to identify and synthesise literature (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010). There remains a paucity of literature that provides explicit guidance to novice nursing researchers on how to conduct an integrative review and importantly how to ensure the results and conclusions are both comprehensive and reliable. Furthermore, novice nursing researchers may receive little formal training to develop the skills required to generate a comprehensive integrative review (Boote and Beile, 2005). Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019) also emphasised the limited literature providing guidance surrounding integrative reviews. Therefore, novice nursing researchers need to rely on published guidance to assist them. In this regard this paper, using an integrative review conducted by the authors as a case study, aims to provide a framework for novice nursing researchers conducting integrative reviews.

Developing the framework

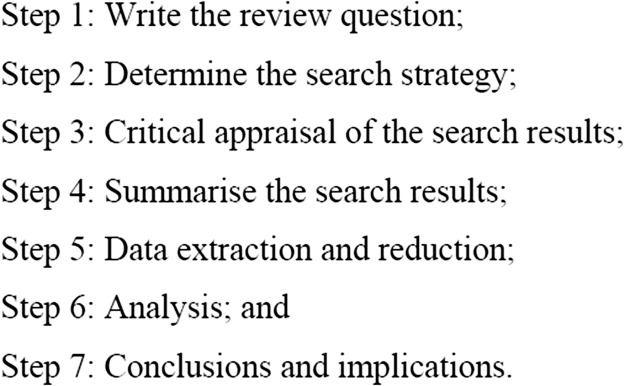

In conducting integrative reviews, the novice nursing researcher may need to employ a framework to ensure the findings are comprehensive and reliable (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010; Snyder, 2019). A framework to guide novice nursing researchers in conducting integrative reviews has been adapted by the authors and will now be described and delineated. This framework used various published literature to guide its creation, namely works by Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones (2019), Nelson (2014), Stern et al. (2014), Whittemore and Knafl (2005), Pluye et al. (2009), Moher et al., (2009) and Attride-Stirling, (2001). The suggested framework involves seven steps (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Integrative review framework (Cooke et al. 2012; Riva et al. 2012).

Step 1: Write the review question

The review question acts as a foundation for an integrative study (Riva et al. 2012). Yet, a review question may be difficult to articulate for the novice nursing researcher as it needs to consider multiple factors specifically, the population or sample, the interventions or area under investigation, the research design and outcomes and any benefit to the treatment (Riva et al. 2012). A well-written review question aids the researcher to develop their research protocol/design and is of vital importance when writing an integrative review.

To articulate a review question there are numerous tools available to the novice nursing researcher to employ. These tools include variations on the PICOTs template (PICOT, PICO, PIO), and the Spider template. The PICOTs template is an established tool for structuring a research question. Yet, the SPIDER template has gained acceptance despite the need for further research to determine its applicability to multiple research contexts (Cooke et al., 2012). Templates are recommended to aid the novice nursing researcher in effectively delineating and deconstructing the various elements within their review question. Delineation aids the researcher to refine the question and produce more targeted results within a literature search. In the case study, the review question was to: identify, evaluate and synthesise current knowledge and healthcare approaches to women presenting due to intimate partner violence (IPV) within emergency departments (ED). This review objective is delineated in the review question templates shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of elements involved with a PICOTS and SPIDER review question.

| PICOTS template | |

| Population | Healthcare professionals |

| Intervention/Interest | Provision of healthcare to women |

| Comparison or Context | No comparator Emergency department context |

| Outcome | Any outcomes |

| Time | No restriction on date of publication was employed to conform to the comprehensive approach utilised. |

| Study design | Integrative: both quantitative and qualitative studies included |

| SPIDER template | |

| Sample | Healthcare professionals within the emergency setting |

| Phenomenon of Interest | Provision of healthcare to women |

| Design | Integrative |

| Evaluation | Any outcomes |

| Research Type | Integrative: both quantitative and qualitative studies included |

Step 2: Determine the search strategy

In determining a search strategy, it is important for the novice nursing researcher to consider the databases employed, the search terms, the Boolean operators, the use of truncation and the use of subject headings. Furthermore, Nelson (2014) suggests that a detailed description of the search strategy should be included within integrative reviews to ensure readers are able to reproduce the results.

The databases employed within a search strategy need to consider the research aim and the scope of information contained within the database. Many databases vary in their coverage of specific journals and associated literature, such as conference proceedings (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010). Therefore, the novice nursing researcher should consult several databases when conducting their searches. For example, search strategies within the healthcare field may utilise databases such as Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Healthcare Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Science Direct, ProQuest, Web of Science, Scopus and PsychInfo (Cronin et al. 2008). These databases among others are largely considered appropriate repositories of reliable data that novice researchers may utilise when researching within healthcare. The date in which the searches are undertaken should be within the search strategy as searches undertaken after this date may generate increased results in line with the publication of further studies.

Utilising an established template to generate a research question allows for the delineation of key elements within the question as seen above. These key elements may assist the novice nursing researcher in determining the search terms they employ. Furthermore, keywords on published papers may provide the novice nursing researcher with alternative search terms, synonyms and introduce the researcher to key terminology employed within their field (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010). For example, within the case study undertaken the search terms included among others: ‘domestic violence’, ‘domestic abuse’, ‘intimate partner violence and/or abuse’. To refine the search to the correct healthcare environment the terms ‘emergency department’ and/or ‘emergency room’ were employed. To link search terms, the researcher should consider their use of Boolean operators ‘And’ ‘Or’ and ‘Not’ and their use of truncation (Cronin et al. 2008). Truncation is the shortening of words which in literature searches may increase the number of search results. Medical subject headings (MeSH) or general subject headings should be employed where appropriate and within this case study the headings included ‘nursing’, ‘domestic violence’ and ‘intimate partner violence’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria allow the novice nursing researcher to reduce and refine the search parameters and locate the specific data they seek. Appropriate use of inclusion and exclusion criteria permits relevant data to be sourced as wider searches can produce a large amount of disparate data, whereas a search that is too narrow may result in the omission of significant findings (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010). The novice nursing researcher needs to be aware that generating a large volume of search results may not necessarily result in relevant data being identified. Within integrative reviews there is potential for a large volume of data to be sourced and therefore time and resources required to complete the review need to be considered (Heyvaert et al. 2017). The analysis and refining of a large volume of data can become a labour-intensive exercise for the novice nursing researcher (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010).

Stern et al. (2014) suggest various elements that should be considered within inclusion/exclusion criteria:

the type of studies included;

the topic under exploration;

the outcomes;

publication language;

the time period; and

the methods employed.

The use of limiters or exclusion criteria are an effective method to manage the amount of time it takes to undertake searches and limit the volume of research generated. Yet, exclusion criteria may introduce biases in the search results and should therefore be used with caution and to produce specific outcomes by the novice nursing researcher (Hammerstrøm et al. 2017).

Whittemore and Knafl (2005) suggest that randomised controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case control studies, cross sectional studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses should all be included within the search strategy. Therefore, there are no biases based on the type of publication sourced (Hammerstrøm et al. 2017).

There should be no restriction on the sample size within the studies recognising that qualitative studies generally have smaller sample sizes, and to capture the breadth of research available. There was no restriction on the date of publication within the case study as quality literature was limited. Scoping widely is an important strategy within integrative reviews to produce comprehensive results. A manual citation search of the reference list of all sourced papers was also undertaken by a member of the research team.

Literature may be excluded if those papers were published in a language foreign to the researcher with no accepted translation available. Though limiting papers based on translation availability may introduce some bias, this does ensure the review remains free from translational errors and cultural misinterpretations. In the case study, research conducted in developing countries with a markedly different healthcare service and significant resource limitations were excluded due to their lack of generalisability and clinical relevance; though this may have introduced a degree of location bias (Nelson, 2014).

A peer review of the search strategy by an individual who specialises in research data searches such as a research librarian may be a viable method in which the novice healthcare researcher can ensure the search strategy is appropriate and able to generate the required data. One such tool that a novice nurse may employ is the Peer Review of the Search Strategy (PRESS) checklist. A peer review of the caste study was undertaken by a research librarian. All recommendations were incorporated into the search strategy which included removing a full text limiter, and changes to the Boolean and proximity operators.

After the search strategy has been implemented the researcher removes duplicate results and screened the retrieved publications based on their titles and abstracts. A second screening was then undertaken based on the full text of retrieved publications to remove papers that were irrelevant to the research question. Full text copies should then be obtained for critical appraisal employing validated methods.

Step 3: Critical appraisal of search results

The papers identified within the search strategy should undergo a critical appraisal to determine if they are appropriate and of sufficient quality to be included within the review. This should be conducted or reviewed by a second member of the research team, which occurred within this case study. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was achieved. A critical appraisal allows the novice healthcare researcher to appraise the relevance and trustworthiness of a study and, therefore, determine its applicability to their research (CASP, 2013). There are several established tools a novice nurse can employ in which to structure their critical appraisal. These include the Scoring System for Mixed-Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews developed by Pluye et al. (2009) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2018) Checklists.

The review undertaken by the authors employed the scoring system for mixed-methods research and mixed-studies reviews developed by Pluye et al. (2009). This scoring system was specifically designed for reviews employing studies from various research designs and therefore was utilised with ease (Table 2).

Table 2.

The scoring system for mixed-methods research and mixed-studies reviews (Pluye et al. 2009).

| Types of mixed-methods study components | Methodological quality criteria | Present/Not Y/N |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Qualitative objective or question Appropriate qualitative approach or design or method Description of the context Description of participants and justification of sampling Description of qualitative data collection and analysis Discussion of researchers’ reflexivity | |

| Quantitative experimental | Appropriate sequence generation and/or randomisation Allocation concealment and/or blinding Complete outcome data and/or low withdrawal/drop-out | |

| Quantitative observational | Appropriate sampling and sample Justification of measurements (validity and standards) Control of confounding variables | |

| Mixed Methods | Justification of the mixed-methods design Combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection-analysis techniques or procedures Integration of qualitative and quantitative data or results |

Using the CASP checklist aids the novice nursing researcher to examine the methodology of identified papers to establish validity. This critical appraisal tool contains 10 items. These items are yes or no questions that assist the researcher to determine (a) if the results of the paper are valid, (b) what the results are and (c) if it is relevant in the context of their study. For example, the checklist asks the researcher to consider the presence of a clear statement surrounding the aims of the research, and to consider why and how the research is important in regard to their topic (CASP, 2013). This checklist supports the nurse researcher to assess the validity, results and significance of research, and therefore appropriately decide on its inclusion within the review (Krainovich-Miller et al., 2009).

Step 4: Summarise the search results

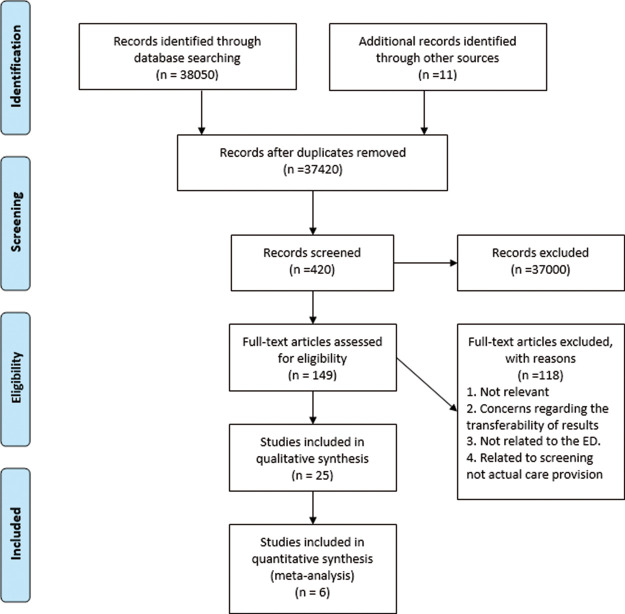

A summary of the results generated by literature searches is important to exemplify how comprehensive the literature is or conversely to identify if there are gaps in research. This summary should include the number of, and type of papers included within the review post limiters, screening and critical appraisal of search results. For example, within the review detailed throughout this paper the search strategy resulted in the inclusion of 25 qualitative and six quantitative papers (Bakon et al. 2019). Many papers provide a summary of their search results visually in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). PRISMA is a method of reporting that enables readers to assess the robustness of the results (Leclercq et al. 2019; Moher et al. 2009). PRISMA promotes the transparency of the search process by delineating various items within the search process (Leclercq et al. 2019; Moher et al. 2009). Researchers may decide how rigorously they follow this process yet should provide a rationale for any deviations (Leclercq et al. 2019; Moher et al, 2009). Figure 2 is an example of the PRISMA flow diagram as it was applied within the case study.

Figure 2.

Example PRISMA flow diagram (Bakon et al. 2019; Moher et al. 2009).

Step 5: Data extraction and reduction

Data can be extracted from the critically appraised papers identified through the search strategy employing extraction tables. Within the case study data were clearly delineated, as suggested by Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic (2010), into extraction or comparison tables (Table 3). These tables specify the authors, the date of publication, year of publication, site where the research was conducted and the key findings. Setting out the data into tables facilitates the comparison of these variables and aids the researcher to determine the appropriateness of the papers’ inclusion or exclusion within the review (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005).

Table 3.

Example of a data extraction table.

| Author | Year | Design | Sample/Site | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fanslow et al. | 1998 | Evaluation | Aus, NZ | Institutional change is paramount for long term improvements in the care provided to intimate partner violence patients. |

Step 6: Analysis

Thematic analysis is widely used in integrative research (Attride-Stirling, 2001). In this section we will discuss the benefits of employing a structured approach to thematic analysis including the formation of a thematic network. A thematic network is a visual diagram or depiction of the themes displaying their interconnectivity. Thematic analysis with the development of a thematic network is a way of identifying themes at various levels and depicting the observed relationships and organisation of these themes (Attride-Stirling, 2001). There are numerous methods and tools available in which to conduct a thematic analysis that may be of use to the novice healthcare researcher conducting an integrative review. The approach used in a thematic analysis is important though a cursory glance at many literature reviews will reveal that many authors do not delineate the methods they employ. This includes the thematic analysis approach suggested by Thomas and Harden (2008) and the approach to thematic networking suggested by Attride-Stirling (2001).

Thomas and Harden (2008) espouse a three-step approach to thematic analysis which includes: (a) coding, (b) organisation of codes into descriptive themes, and (c) the amalgamation of descriptive themes into analytical themes. The benefit of this approach lies in its simplicity and the ease with which a novice nurse researcher can apply the required steps. In contrast, the benefit of the approach suggested by Attride-Stirling (2001) lies in its ability to move beyond analysis and generate a visual thematic network which facilitates a critical interpretation and synthesis of the data.

Thematic networks typically depict three levels: basic themes, organising themes and global themes (Attride-Stirling, 2001). The thematic network can then be developed. A thematic network is a visual depiction that appears graphically as a web like design (Attride-Stirling, 2001). Thematic networks emphasise the relationships and interconnectivity of the network. It is an illustrative tool that facilitates interpretation of the data (Attride-Stirling, 2001).

The benefits of employing a thematic analysis and networking within integrative reviews is the flexibility inherent within the approach, which allows the novice nursing researcher to provide a comprehensive accounting of the data (Nowell et al. 2017). Thematic analysis is also an easily grasped form of data analysis that is useful for exploring various perspectives on specific topics and highlighting knowledge gaps (Nowell et al. 2017). Thematic analysis and networking is also useful as a method to summarise large or diversified data sets to produce insightful conclusions (Attride-Stirling, 2001; Nowell et al. 2017). The ability to assimilate data from various seemingly disparate perspectives may be challenging for the novice nursing researcher conducting an integrative review yet this integration of data by thematic analysis and networking was is integral.

To ensure the trustworthiness of results, novice nursing researchers need to clearly articulate each stage within the chosen method of data analysis (Attride-Stirling, 2001; Nowell et al. 2017). The method employed in data analysis needs to be precise and exhaustively delineated (Attride-Stirling, 2001; Nowell et al. 2017). Attride-Stirling (2001) suggests six steps within her methods of thematic analysis and networking. These steps include:

code material;

identify themes;

construct thematic network;

describe and explore the thematic network;

summarise thematic network findings; and

interpret patterns to identify implications.

In employing the approach suggested by Attride-Stirling (2001) within the case study the coding of specific findings within the data permitted the development of various themes (Table 4). Inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative findings within the themes facilitated integration of the data which identified patterns and generated insights into the current care provided to IPV victims within ED.

Table 4.

Coding and theme formation.

| Article | Text Segment | Code | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loughlin et al. (2000) | ‘the translation of protocols into practice is less well researched.’ | FR-EV | Frameworks for intimate partner violence care provision |

| Fanslow et al. (1998) | ‘while the protocol produced initial positive changes in the identification and acute management of abused women, these changes were not maintained.’ | FR-NEG |

Step 7: Conclusions and implications

A conclusion is important to remind the reader why the research topic is important. The researcher can then follow advice by Higginbottom (2015) who suggests that in drawing and writing research conclusions the researcher has an opportunity to explain the significance of the findings. The researcher may also need to explain these conclusions in light of the study limitations and parameters. Higginbottom (2015) emphasises that a conclusion is not a summary or reiteration of the results but a section which details the broader implications of the research and translates this knowledge into a format that is of use to the reader. The implications of the review findings for healthcare practice, for healthcare education and research should be considered.

Employing this structured and comprehensive framework within the case study the authors were able to determine that there remains a marked barrier in the provision of healthcare within the ED to women presenting with IPV-related injury. By employing an integrative approach multiple forms of literature were reviewed, and a considerable gap was identified. Therefore, further research may need to focus on the developing a structured healthcare protocol to aid ED clinicians to meet the needs of this vulnerable patient population.

Conclusion

Integrative reviews can be conducted with success when they follow a structured approach. This paper proposes a framework that novice nursing researchers can employ. Applying our stepped framework within an integrative review will strengthen the robustness of the study and facilitate its translation into policy and practice. This framework was employed by the authors to identify, evaluate and synthesise current knowledge and approaches of health professionals surrounding the care provision of women presenting due to IPV within emergency departments. The recommendations from the case study are currently being translated and implemented into the practice environment.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Integrative literature reviews are required within nursing to consider elements of care provision from a holistic perspective.

There is currently limited literature providing explicit guidance on how to undertake an integrative literature review.

Clear delineation of the integrative literature review process demonstrates how the knowledge base was understood, organised and analysed.

Nurse researchers may utilise this guidance to ensure the reliability of their integrative review.

Biography

Shannon Dhollande is a Lecturer, registered nurse and researcher. Her research explores the provision of emergency care to vulnerable populations.

Annabel Taylor is a Professorial Research Fellow at CQ University who with her background in social work explores methods of addressing gendered violence such as domestic violence.

Silke Meyer is an Associate Professor in Criminology and the Deputy Director of the Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre at Monash University.

Mark Scott is an Emergency Medical Consultant with a track record in advancing emergency healthcare through implementation of evidence-based healthcare.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics: Due to the nature of this article this article did not require ethical approval.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Shannon Dhollande, Lecturer, School of Nursing, Midwifery & Social Sciences, CQ University Brisbane, Australia.

Annabel Taylor, Professor, School of Nursing, Midwifery & Social Sciences, CQ University Brisbane, Australia.

Silke Meyer, Associate Professor, School of Social Sciences, Monash University, Australia.

Mark Scott, Emergency Consultant, Emergency Department, Caboolture Hospital, Australia.

ORCID iDs

Shannon Dhollande https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3181-7606

Silke Meyer https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3964-042X

References

- Attride-Stirling J. (2001) Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 1(3): 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard H, Bradbury-Jones C. (2019) An analysis of current practices in undertaking literature reviews in nursing: Findings from a focused mapping review and synthesis. BMC Medical Research Methodology 19(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakon S, Taylor A, Meyer S, et al. (2019) The provision of emergency healthcare for women who experience intimate partner violence: Part 1 An integrative review. Emergency Nurse 27: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boell S, Cecez-Kecmanovic D. (2010) Literature reviews and the Hermeneutic circle. Australian Academic & Research Libraries 41(2): 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Boell S, Cecez-Kecmanovic D. (2015) On being systematic in literature reviews. Journal of Information Technology 30: 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Boote D, Beile P. (2005) Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher 34(6): 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. (2012) Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research 22(10): 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2018) CASP Checklists. casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists.

- Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. (2008) Undertaking a literature review: A step by step approach. British Journal of Nursing 17(1): 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstrøm K, Wade A, Jørgensen A, et al. (2017) Searching for relevant studie. In: Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. (eds) Using Mixed Methods Research Synthesis for Literature Reviews, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert M, Maes B, Onghena P, et al. (2017) Introduction to MMRS literature reviews. In: Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. (eds) Using Mixed Methods Research Synthesis for Literature Reviews, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom G. (2015) Drawing conclusions from your research. In: Higginbottom G, Liamputtong P. (eds) Participatory Qualitative Research Methodologies in Health, London: SAGE, pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Krainovich-Miller B, Haber J, Yost J, et al. (2009) Evidence-based practice challenge: Teaching critical appraisal of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines to graduate students. Journal of Nursing Education 48(4): 186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq V, Beaudart C, Ajamieh S, et al. (2019) Meta-analyses indexed in PsycINFO had a better completeness of reporting when they mention PRISMA. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 115: 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppäkoski T, Paavilainen E. (2012) Triangulation as a method to create a preliminary model to identify and intervene in intimate partner violence. Applied Nursing Research 25: 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson H. (2014) Systematic Reviews to Answer Health Care Questions, Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell L, Norris J, White D, et al. (2017) Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16(1): 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pluye P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, et al. (2009) A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies 46: 529–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluye P, Hong Q, Bush P, et al. (2016) Opening up the definition of systematic literature review: The plurality of worldviews, methodologies and methods for reviews and syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 73: 2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva JJ, Malik KM, Burnie SJ, et al. (2012) What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 56(3): 167–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C. (2005) An overview of the integrative research review. Progress in Transplantation 15(1): 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. (2019) Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 104: 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Soares C, Hoga L, Peduzzi M, et al. (2014) Integrative review: Concepts and methods used in nursing. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 48(2): 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza M, Silva M, Carvalho R. (2010) Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 8(1): 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A. (2014) Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. American Journal of Nursing 114(4): 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Harden A. (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torraco R. (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review 4(3): 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. (2005) The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52(5): 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]