Abstract

Background

Massive open online courses have the potential to enable dissemination of essential components of quality improvement learning. Subsequent to conducting the massive open online course ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’, this paper is a report of the evaluation of the course’s effectiveness in increasing healthcare professionals’ quality improvement knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy and systems thinking.

Methods

Using the Kirkpatrick model for evaluation, a pretest–posttest design was employed to measure quality improvement knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking. Interprofessional learners across the globe enrolled in the 5-week online course that consisted of 10 modules (short theory bursts, assignments and assessments). The objective of the course was to facilitate learners’ completion of a personal or clinical project. Of the 5751 learners enrolled, 1415 completed the demographic survey, and 88 completed all the surveys, assignments and assessments. This paper focuses on the 88 who completed the course.

Results

There was a significant 14% increase in knowledge, a 3.5% increase in positive attitude, a 3.9% increase in systems thinking and a 21% increase in self-efficacy. Learners were very satisfied with the course (8.9/10).

Conclusions

Learners who completed the course ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ had significant gains in learner outcomes: quality improvement knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking supporting this course format’s efficacy in improving key components of students’ quality improvement capabilities.

Keywords: change strategies, improvement, interprofessional, online learning, quality competence, systems thinking

Introduction

Gaps in healthcare quality and safety are a critical national and international problem (Institute of Medicine, 2003; World Health Organization, 2014) and often result in death. In the United States, as many as 440,000 deaths per year occur from preventable medical errors in hospitals (James, 2013). Consumers, healthcare professionals, insurers, governmental agencies, accrediting agencies and healthcare systems are demanding decreases in preventable medical errors and subsequent morbidity and mortality. Quality improvement (QI) is a method to address these gaps to improve quality and safety and is a core competency of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), now the National Academy of Medicine (NAM). As world healthcare systems are burdened with the excessive demands and challenges of a rapidly evolving global pandemic, healthcare practitioners need to have methods to identify and alter practices to improve quality and achieve optimal patient outcomes. The reach of massive open online courses (MOOCs) allows for the dissemination of QI learning at a global scale.

Whereas healthcare professions education programmes now embed QI competency in curricula, and the competencies are included in accreditation standards for healthcare professions' education, older more experienced practitioners often lack preparedness for involvement in QI activities, both in attitudes and skills. A cross-sectional comparative study (Djukic et al., 2013a) found that many newly graduated nurses report never having been involved in key QI processes such as measurement for current performance, gap analysis, use of tools to improve performance, systems improvement, or root cause analysis. Building on the analysis performed in their 2012 study, the same authors found (Djukic et al., 2013b) that overall less than 25% of nurses in the study reported being well prepared for involvement in QI activities. These findings warrant the development of methods for providing continuing education and training in QI methods for veteran practitioners.

At our academic institution, we have offered a healthcare QI course for graduate students since 1999. The aim is to assist learners to lead successful improvement projects by having them conduct a successful first round iteration of a QI project (Dolansky et al., 2009). With this experience and expertise, we developed and evaluated a MOOC on healthcare QI to provide the curriculum to a global audience of frontline healthcare providers, students and faculty.

The purpose of this paper is to report the evaluation of the effectiveness of the QI course, ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’, delivered as a MOOC. This evaluation can inform future online QI course design. This study sought to answer the following questions: (a) Are there changes in learner QI knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking after taking the ‘Take the lead on healthcare quality improvement’ MOOC? (b) What are the demographic characteristics of the learners in the MOOC? And (c) What is the learners’ satisfaction with the course?

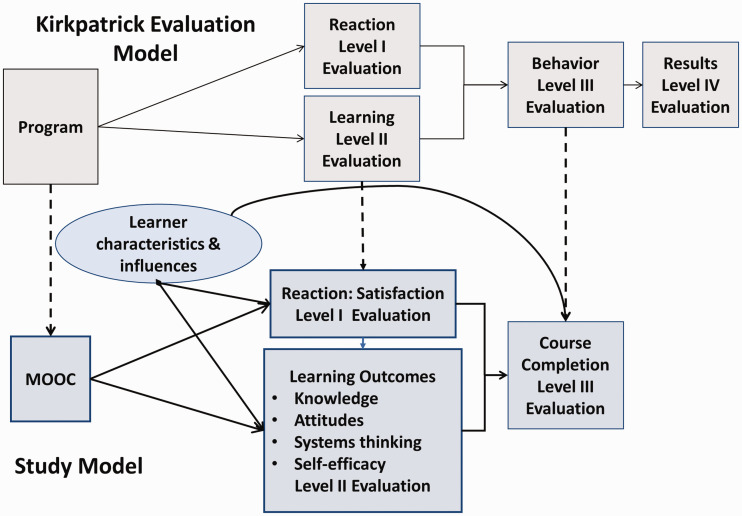

Using evaluation instruments and the Kirkpatrick evaluation model (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick, 2006), data were gathered on learners’ characteristics and pre- and post-course QI knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking. The Kirkpatrick model (Figure 1), level I consists of a measurement of learner reaction to (satisfaction) the course, level II includes measures of learning (knowledge, attitudes, systems thinking, self-efficacy) and level III consists of measures of behaviour change (course and required project completion).

Figure 1.

Study Model.

Development of the MOOC ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ serves an urgent need to educate healthcare professionals about QI techniques and provide a sequential programme to guide learners in the successful completion of a QI project. A long established and extensively evaluated and revised traditional classroom course on QI was the foundation for this MOOC. The book Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (Ogrinc et al., 2012) served as the textbook and outline for both the traditional course and the MOOC. In transforming this course from in-person classroom delivery to the MOOC platform, it is relevant to note that the textbook is in PDF format, the lecture content is provided by way of video lectures created specifically for the MOOC, graduate teaching assistants serve as online discussion board mediators and course problem solvers, and the PDF project worksheets are peer evaluated by other MOOC learners. All of these elements create robust and supported learning within the course.

In general, MOOCs differ from traditional online educational offerings in their unlimited enrolment (massive), lack of barriers to enrolment (open) and subsequently in the impact that these two factors have on course dynamics. There is evidence of growing interest in the global uses of MOOCs for a variety of purposes including: continuing education in professional development, academic course content, public health education, career advancement and improving patient health literacy (Gooding et al., 2013; Liyanagunawardena and Williams, 2014; Milligan and Littlejohn, 2014; Stathakarou et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014).

The MOOC ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ consists of 10 online modules over a 5-week period. All learning activities and assessments are completed online. Each MOOC module includes QI content delivered using video lectures, assignments, discussion board questions and peer-graded sequential assignments in conducting a personal or clinical QI project (Table 1). The video lectures are presented by QI faculty experts from the sponsoring institution as well as other expert guest lecturers. The expected time commitment is 5–7 hours a week. All course material is available asynchronously. There were other interactive aspects offered during the initial two times the course was offered such as a live meeting with course faculty, a Facebook page and an interactive world map.

Table 1.

Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement.

| Module agenda |

Reading pre-work |

Video theory 20 minutes |

Application 10 minutes |

Assignment |

Reflective exercises 10 minutes |

Lessons learned from experts 10 minutes |

Evaluation 10 minutes |

| WEEK 1 | |||||||

| 1 | Required: USDHHS-HRSA quality improvement part 1 pages 1–6 Recommended: Fundamentals book Forward and chapter 1 | Overview of healthcare quality improvement | Worksheet goal Team members Step 1: Problem identification -Global aim -Baseline data | Goal Team Global aim Baseline data | Dr Wes Self Emergency room project & blood cultures | Duncan Neuhauser PhD | Questions |

| 2 | Required: http://www.dartmouth.edu/∼biomed/resources.htmld/guides/ebm_resources.shtml Recommended: Fundamentals book Chapter 2: finding scientific evidence | Evidence for improvement work: Literature, internet & more | Worksheet Step 2: Link current evidence | Literature & industry assessment | Discussion board: Reflect & comment on another student’s work. | David C Aron MD, MS | Questions |

| WEEK 2 | |||||||

| 3 | Required: Recommended: Fundamentals book Chapter 3: Working in interprofessional teams | Interprofessional teams for improvement of healthcare | Worksheet Step 3: Understand the process-context | Organisational readiness assessment | Discussion board: Reflect and comment on who is on the team | Nancy M Tinsley RN, MBA, FACHE | Questions & checklist |

| 4 | Required: Recommended: Fundamentals book Chapter 5: Process literacy | Knowledge of systems & processes | Worksheet Step 3: Understand the process- diagnosis of system performance | Process map Fishbone | Discussion board: What is the context in which the improvement project is occurring in | Shirley M Moore PhD, RN, FAAN | Questions & checklist |

| Module agenda |

Pre-work readings |

Video theory 20 minutes |

Application 10 minutes |

Assignment |

Reflective exercises 10 minutes |

Lessons learned from experts |

Evaluation 10 minutes |

| WEEK 3 | |||||||

| 5 | Required: Recommended: Fundamentals book Chapter 4: Targeting an improvement effort | Targeting your aim from global to specific | Worksheet Step 4: Specific aim | Timeline specific aim | Discussion board: Answers to a case study. | Questions & checklist | |

| 6 | Required: Recommended: Chapter 6 Measurement part 1 | Measuring for improvement | Worksheet Step 5: Measures | Measures: outcome, process, balancing | Questions & checklist | ||

| WEEK 4 | |||||||

| 7 | Required: Recommended: Control charts 101 Fundamentals Book: Chapter 7 Measurement part 2 | Data, variation, and control charts | Practice with control charts | Run chart of data | Discussion board: Patterns observed in the data collected. | Brook Watts MD, MS | Questions & checklist |

| 8 | Required: Recommended: Fundamentals book: Chapter 8 | Human side of QI: Psychology of change | Worksheet Step 6: Identify and choose a change idea | Change idea and facilitators & barriers | Discussion board: Problem & issues | Mamta Singh MD | Questions & checklist |

| WEEK 5 | |||||||

| 9 | Required: Recommended: Fundamentals book: Chapter 9 spreading Improvements | Implementing and spreading change: the power of the model for improvement | Worksheet Step 7: Pilot test the change idea | Field notes from implementation | Discussion board | Farrohk Alemi PhD | Questions & checklist |

| 10 | Required: Recommended: | Putting it all together & leading change | Story board | Questions & checklist |

USDHHS-HRSA: United States Department of Health and Human Services: Health Resources and Services Administration.

Methods

This study employed a pre-test, post-test descriptive design comparing QI knowledge, attitude and systems thinking, and pre- and post-module self-efficacy. Collection and analysis of learner demographic and learner satisfaction data were also part of the study.

Participants and setting

The participants were self-selected learners in the MOOC ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ offered on the Coursera platform between 19 October 2014 and 3 December 2014. The platform’s quizzing and data analytics functions served as the data collection and analysis vehicles. The intended audience was interprofessional healthcare members and students who desired to learn about QI.

The course is free and open to anyone with a Coursera account. The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) website and ads in university publications as well as fliers distributed at nursing and QI conferences were the marketing methods for the MOOC. Coursera also markets to its members. There are two levels of enrolment on the Coursera site: the free, standard enrollment and the fee-based Signature Track (US$49) in which Coursera verifies the identity of the learner and provides a certificate on completion of the course. Continued education credits in nursing were also available at an additional cost during the programme evaluation.

Of the 5751 participants enrolled in the course, 1415 provided demographic data in the pre-course survey. There were 110 (1.9%) who completed the course according to the criteria established in the course syllabus. Of the 140 enrolled in Signature Track (participants who paid a fee to receive a certificate), 48 (34.3%) completed the course requirements. Sixteen participants completed the entire course for continuing nursing education credit. One hundred and one learners completed the post-course survey. Eighty-eight participants completed all pre- and post-course assessments and surveys, pre- and post-module assessments and course evaluations.

Procedures

Learners enrolled in the Coursera course and were asked to complete pre-course assessments that included learner demographic data and pre-course assessments of QI knowledge, attitude and systems thinking. While participating in each of the individual modules, learners were asked to complete pre- and post-module self-efficacy assessments and post-module knowledge assessments. Each MOOC module included asynchronous learning by video lectures, assignments, moderated discussion boards and sequentially developed peer-reviewed QI projects. The final project was a storyboard that documented the process and outcomes of their QI project assignment. At completion of the course, learners were asked again to complete the assessments of QI knowledge, QI attitude and systems thinking, and to do a post-course satisfaction survey.

For the evaluation of the course, data analysis was performed using SPSS. A t-test was used to assess the differences between the demographic variables of those who completed the MOOC (N = 88) and those who did not (N = 1415). A paired t-test was used to assess the differences between pre- and post-test on knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking. In addition, a percentage improvement for each of the outcome variables was reported.

Measures

In Kirkpatrick level II, evaluation of participant learning, participants engage in assessments designed to measure knowledge increase, what skills were developed or improved and what attitudes were changed (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick, 2006). The importance of measuring change in knowledge and attitude is that these measure learning, a necessary step to behaviour change. A measure of systems thinking was included in this evaluation because the ability to engage in systems thinking has been identified as a critical factor in QI (Dolansky and Moore, 2013; Dolansky et al., 2020). Learner self-efficacy was included as a measure of learner confidence in QI concepts and processes.

QI knowledge

QI knowledge refers to QI concepts and ideas acquired by study, investigation or experience. QI knowledge was measured using a self-report knowledge questionnaire containing 15 questions selected from course content. The score was based on the number of correct answers divided by 15 and multiplied by 100. The possible score range is 0 to 100. Higher scores indicated greater QI knowledge. The pre- and post-course knowledge assessments were identical. The knowledge assessments were created by two of the investigators based on content from course textbooks and other course materials. Content validity was corroborated by a QI expert.

QI attitude

QI attitude is a predisposition to value the improvement of quality and to be willing to take necessary actions to implement QI activities. It is the manifestation of the affective realm of learning and is related to motivational disposition and self-efficacy (Kraiger et al., 1993). QI attitude was measured using an adapted version of the Macy CoVE Quality Improvement Attitude and Knowledge Survey (American Board of Internal Medicine, n.d., unpublished manuscript). This survey consisted of 15 items to which participants responded on a Likert-type scale: (0, strongly disagree to 4, strongly agree). Scores were calculated by summing the numbers corresponding to the responses with possible scores ranging from 0 to 60. Higher numbers indicated a more favourable attitude towards QI. The internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the QI attitude for our evaluation was adequate (alpha = 0.81).

Systems thinking

Systems thinking is the ability to recognise, understand and synthesise the interactions and interdependencies in a set of components designed for a specific purpose, including the ability to recognise patterns and repetitions in the interactions and an understanding of how actions and components can reinforce or counteract each other. Systems thinking was measured using the 20-item Systems Thinking Scale (STS) (Dolansky et al., 2020). The STS has established reliability: internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.82) and test–retest reliability (correlation 0.74). Participants respond to each item on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0, never to 4, most of the time). A sum of these items provides the STS score, which can range from 0 to 80. Higher scores indicate higher levels of systems thinking.

QI self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the confidence one has in their ability to perform a specific behaviour (Bandura, 1977, 1986). QI self-efficacy was measured both pre- and post-completion of the learning modules using an adapted version of the Quality Improvement Confidence Instrument (QICI) (Hess et al., 2013). Participants rated their confidence using a Likert-type scale (1, not at all confident to 5, very confident). The total number of items throughout the 10 modules was 51,with a possible range of scores of 51–255, higher scores reflected more self-efficacy regarding their QI capabilities. The score was the sum of Likert ratings on all items from all modules.

Learner characteristics

The following demographic data were collected: gender, age, ethnicity, country of birth, country of residence, urban/rural living status, urban/rural working status, employment status, worksite type, healthcare profession type, job title, level of education, student status and type of industry where employed. Measure of satisfaction consisted of two items on the post-course Coursera customised survey. Items included overall satisfaction with the course using a Likert-type scale (1, poor to 5, excellent) and an item asking the likelihood of recommending the course to a friend or colleague using a Likert-type scale (1, very unlikely to 5, very likely). Scores were calculated by summing the responses on the two items and can range from 0 to 10 with higher numbers indicating higher course satisfaction.

Results

Learner characteristics

Of the 5751 participants enrolled in the course, 1415 provided demographic data in the pre-course survey and are considered the whole sample for this study. Of the total number of enrollees, there were 88 (1.5%) who completed all surveys and assessments; 6.2% of those who completed the demographic survey completed the course. The mean age of participants for the whole sample was 41.6 years (standard deviation 12.8; range 17–85 years) and the mean age of the participants who completed all the surveys was 44.0 years (standard deviation 13.0; range 43–70 years). Table 2 provides a comparison of the demographic characteristics of those who completed the demographic survey at the beginning of the MOOC and those who completed the course requirements. On the whole, the two groups had similar demographic profiles, with the largest differences observed in gender, race, work location and educational and professional credentials.

Table 2.

Comparison of the demographic characteristics of the whole sample and the participants who completed the course.

| Whole sample N = 1415 N (%) | Course completed N = 88 N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 917 (64.8%) | 62 (70.5%) |

| Male | 492 (34.8%) | 26 (29.5%) |

| Other | 6 (<1%) | – |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 827 (58.4%) | 55 (62.5%) |

| Asian | 307 (21.7%) | 18 (20.5%) |

| Black or African American | 163 (11.5%) | 5 (6%) |

| Other | 118 (8.3%) | 10 (11.4%) |

| Country of residence | ||

| USA | 766 (54.1%) | 50 (56.8%) |

| Other | 649 (45.9%) | 38 (43.2%) |

| Work location | ||

| Urban | 1021 (72.2%) | 59 (67%) |

| Suburban | 164 (11.6%) | 9 (10.2%) |

| Town | 125 (8.8%) | 8 (9.1%) |

| Rural | 55 (3.9%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Other | 50 (3.5%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 1076 (76.0%) | 68 (77.3%) |

| Part-time | 149 (10.5%) | 8 (9.1%) |

| Unemployed | 139 (9.8%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Other | 51 (3.6%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Worksite | ||

| Hospital | 554 (39.2%) | 36 (40.9%) |

| Academic institution | 246 (17.4%) | 19 (21.6%) |

| Long term/rehab | 35 (2.5%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Outpatient settings | 167 (11.8%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| School nurse | 38 (2.7%) | 6 (6.8%) |

| Not currently employed | 97 (6.9%) | 8 (9.1%) |

| Other | 278 (19.6%) | 16 (18.2%) |

| Education | ||

| Less than bachelors | 164 (11.6%) | 5 (5.7%) |

| Bachelors | 371 (26.2%) | 20 (22.7%) |

| Masters | 487 (34.4%) | 32 (36.4%) |

| Professional school degree | 198 (14.0%) | 10 (11.4%) |

| PhD, EdD | 195 (13.8%) | 21 (23.9%) |

| Credentials | ||

| RN, APRN | 434 (28.9%) | 30 (34.1%) |

| MD/DO | 250 (17.8%) | 12 (13.6%) |

| PhD | 79 (5.6%) | 15 (17%) |

| PT/OT | 28 (2%) | – |

| PharmD | 27 (1.92%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Other | 402 (28.7%) | 30 (34.1%) |

| No credential | 182 (11.3%) | – |

APRN: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse; EdD: Doctor of Education; MD/DO: Medical Doctor/Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine; PharmD: Doctor of Pharmacy; PT/OT: Physical Therapist/Occupational Therapist; RN: Registered Nurse.

Changes in learner QI knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking

Table 3 provides a summary of the differences in learner QI knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking before and after taking the ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ MOOC. There was a significant 14% increase in QI knowledge, a 3.5% increase in QI attitude, a 3.9% increase in systems thinking and a 21% increase in QI self-efficacy.

Table 3.

Differences in pre- to post-test scores (N = 88).

| Pre-test |

Post-test |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T | |

| Knowledge | 10.2 | 1.8 | 12.3 | 2.2 | 9.7 |

| Attitude | 40.0 | 6.7 | 42.1 | 7.8 | 3.3 |

| Systems thinking | 60.9 | 12.4 | 63.9 | 10.8 | 2.4 |

| Self-efficacy | 170.6 | 46.0 | 223.5 | 25.2 | 12.9 |

SD: standard deviation.

All values significant at the P < 0.05 level.

Learner satisfaction with course

Learners indicated that they would recommend the course to others (4.5/5). Learners rated satisfaction with the course high (4.4/5). Total satisfaction was high for all samples (8.9/10), and was calculated as the sum of the rating of likelihood of recommending the course to others and overall rate of satisfaction.

Discussion

Findings from our study indicate that the ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ MOOC was an effective educational intervention for learning and doing QI at the personal or workplace level. Learners who completed all modules, assignments and assessments of the ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ MOOC had statistically significant gains in learner outcomes: QI knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking. Employing MOOCs has the potential to increase the capacity of professionals to improve healthcare quality by reaching large numbers of geographically dispersed practitioners quickly.

Learners entered the course with diverse professional and topic expertise, including many with prior QI knowledge; this was reflected in the pre-course knowledge assessment, with more than two-thirds of the questions answered correctly. Despite high pre-test scores, the significant improvements in post-test QI knowledge scores support the MOOC format as an effective pedagogy. It is known that attitudes influence the use and application of a set of new behaviours (in this case, QI methods) (Kraiger et al., 1993). The significant increase in the participants’ attitude about the importance of interdisciplinary teamwork in learning QI processes was also an interesting finding, and supports the possibility of participants incorporating QI work in their clinical settings.

QI is based on the critical skill of systems thinking. Our study used a reliable and valid measure of systems thinking (Dolansky et al., 2020) to assess learners’ changes in levels of systems thinking resulting from a MOOC-delivered course in QI. Our finding of a significant increase in participant systems thinking scores from pre-test to post-test provides beginning evidence that course content on systems thinking delivered in a MOOC format can improve knowledge of this process. Healthcare practitioners’ use of systems thinking skills has the potential to assist them to move along a continuum of self-reflection on gaps in their own practice to larger systems solutions that exist, allowing for analytical and systematic improvement to enhance patient outcomes (Dolansky and Moore, 2013).

Learner self-efficacy scores (reflecting their confidence in QI concepts and process mastery) showed the highest increase from course pre-test to post-test compared to our other factors evaluated. This finding that a MOOC-delivered course in QI can produce this level of improvement in self-efficacy is consistent with other assessments of QI education using more traditional course delivery formats (Baernholdt et al., 2019; Gregory et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2018). The large improvement in learner self-efficacy found in this study is important because, in general, higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with higher levels of performing a behaviour (Artino, 2012). Thus, when learners feel more confident, they may engage more frequently in QI activities in their clinical settings. There are no reports of this in the literature in longitudinal studies, however, and this warrants further study.

The Kirkpatrick evaluation model elaborates four components of training evaluation: evaluation of participant reaction (level I), participant learning (level II), participant behaviour (level III) and results (level IV) (see Figure 1). For this project, evaluation was completed at levels I, II and III. The advantage to using the Kirkpatrick evaluation model is that it provided feedback on reaction, objective learning and application of the learning as observed in completion of a QI project. Looking forward, it would be useful if the participants in this course were studied longitudinally for learning persistence and clinical level behavioural change which corresponds to Kirkpatrick level IV. This study contributes to our understanding of the effectiveness of using a MOOC platform to teach QI.

Learner characteristics

A striking finding from the demographic data was the interprofessional and geographical diversity of the participants that differs from most face-to-face classroom settings where there is less professional, worksite and geographical diversity, as well as less variation in levels of QI expertise. While designed as an interprofessional course, the variety of professions represented was surprising. Development of this MOOC was spearheaded by the nursing and medicine faculty who anticipated that learners would be nurses and physicians. Extramural institutional-level marketing was primarily aimed at nurses. Approximately 50% of our learners were nurses and doctors and the other 50% were academic faculty, administrators, allied health professionals, information technologists and quality and safety professionals. This diversity of disciplines who took the course affirmed the interprofessional nature and appeal of QI processes and methods. Also, the global reach of MOOCs is touted by proponents, and our MOOC attracted a global audience similar to the geographical reach of other Coursera MOOCs. Our participants were highly educated, which is consistent with studies of other MOOC participant demographics, in which nearly 85% of MOOC participants have baccalaureate degrees or above (Jordan, 2014). The high education levels of our MOOC participants may be due to the specialised nature of the topic and with the target audience of healthcare professionals.

Learner participation and satisfaction

Our course completion rate of 1.5% was considerably lower than the MOOC completion rate of 6.5% reported by Jordan (2014) in a survey of 279 MOOCs. We believe, however, that our criteria of completion of all course modules and assessments for the evaluation of participant learning may contribute to underestimating the impact of our course. Although our formal evaluation consisted of our 88 ‘completers’, nearly 2000 unique learners watched streaming course videos 18,958 unique times, and videos were downloaded 15,128 times. Thus, more learning than what was evaluated may have occurred. Even if only a fraction of the videos was watched by the target audience, some learning that was not formally evaluated is likely to have occurred. In MOOCs, learners interact with the educational materials in a variety of ways and not necessarily in ways envisioned by the course creators. This aligns with data from Perna et al. (2014), who found that lectures were accessed by more course participants than those who attempted quizzes. These authors also explore the sequential instructor-designed progression through the course compared to the user-driven interface with the course. Learners in MOOCs, especially if they are not driven by a goal of certificate attainment, know when they have learned the material that they intended to learn. The learners in this course were adult learners and professionals and they were likely to have made decisions about what was valuable to them and to have stopped when they reached that point. Such learners seem unlikely to adhere rigidly to the pre-designed path of a MOOC. The data from the completers of our MOOC indicate that they were very satisfied with the course; scores indicated high overall levels of satisfaction with the course and that they would highly recommend the course to others.

Study limitations

The results of this MOOC evaluation report should be considered in light of several limitations. These include possible subject evaluation burden, small course completion rate, lack of data on reasons for non-completion of the course, and lack of data on satisfaction levels of non-completers.

This MOOC placed a heavy evaluation burden on learners, which may have contributed to the low percentage of course completers. Pre-course demographic and entrance surveys, pre- and post-course assessments of QI knowledge, QI attitude, and systems thinking and pre- and post-module assessments of QI self-efficacy as well as a post-course survey were administered. These evaluation assessments were embedded and may have contributed to decreased MOOC completion rates.

Lack of data on non-completers is another limitation of this study. As indicated above, information about reasons that individuals did not complete the course or what portions of it they found useful or not, would provide our evaluation team with data on which to make improvements in the MOOC and identify target markets for the course in the future. Exploring why learners left the course before completion might lead to ideas for maintaining their engagement for future MOOC sessions. Unfortunately, data on satisfaction were gathered in the post-course survey, a voluntary assessment completed only by learners reaching the end of the course, thus we do not have satisfaction data from most of our course non-completers.

Impact of the MOOC ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’

The online course ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ specifically contributes to learning healthcare systems by providing virtual, easily accessible and free education for front-line staff. The course offers learners the opportunity to complete the modules asynchronously and is experiential as participants can apply the learning in practice. Thus, learning healthcare systems increase the numbers of ‘QI ready’ staff who can continue to work on interprofessional teams to address the gaps in care and improve clinical outcomes. In academia, students at all levels of education (baccalaureate to doctorate of nursing practice) can participate in the course. This is especially helpful when faculty do not have the expertise to teach the QI content. Doctorate of nursing practice students can use the course as practicum hours that contribute to their practice change project. This added value of the doctorate of nursing practice degree that has an impact on clinical improvement will be well received by administrators and hospital system leaders.

The publication of these findings is particularly relevant now during the Covid-19 pandemic. There is a resurgence of MOOCs as one type of online education for both students and healthcare professionals (Lohr, 2020). With people confined to their homes and looking to acquire skills to enhance employment security, there is increased enrollment in MOOCs. In addition, in the rapid move to online content delivery of courses in the spring semester 2020, several MOOC platforms offered content from their courses to colleges to support student success (Young, 2020).

Future research on effective learning using a MOOC platform is necessary to increase our confidence in the greater use of this format as a learning modality. Two areas of enquiry that are needed are analytics of learner behaviours regarding engaging with MOOCs and self-regulation of learning using MOOCs. Our findings indicate that considerably more information about how different individuals interact with different MOOC learning components is needed, as well as what keeps individuals engaged in the learning. As evidence is accrued about the use and usefulness of the MOOC platform for QI learning, such as that evaluated in this report, we will be able to determine if MOOCs are an effective approach for educating healthcare professionals about QI. It is envisioned that a series of MOOCs could be developed that align with the IOM/NAM quality and safety competencies and could be offered as a specialisation on Coursera. Such a constellation of MOOCs could result in achievement of the IOM/NAM competencies of healthcare professionals.

Summary

Our study provided data on the effectiveness of using a MOOC platform to teach QI improvement and demonstrated improvement in QI knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking. Using the Kirkpatrick evaluation model, our team focused on three of the four components of the model: participant reaction (level I), participant learning (level II) and participant behaviour (level III). Moving forward, it would be useful if the participants in a QI MOOC were studied longitudinally for learning sustainability and behavioural change (Kirkpatrick level IV).

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

A massive open online course on healthcare quality improvement is an effective way to provide a curriculum to a global cadre of frontline nurses.

Participants completing the quality improvement course had improvements in knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking.

Integration of the ‘Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement’ course can be integrated in nursing professional development.

Future evaluation on the sustainability of gains in knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and systems thinking is warranted.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) are grateful for the skillful and attentive work of James Petras, BA, MBA Project Manager, University Technology, CWRU. He served as liaison between the MOOC team and Coursera in the extraction of the data used in the evaluation of the MOOC. Thanks go to the QSEN Institute for sponsoring and marketing the MOOC.

Biography

Denice Reese, APRN DNP CHSE is a Professor of Nursing at Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, WV, USA, where she teaches pharmacology and pediatric nursing in the college's associate and baccalaureate nursing programs. In addition, she teaches courses in healthcare ethics and healthcare quality and safety in the college's online RN to BSN program. She coordinates the healthcare simulation lab. She is a Certified Pediatric Nurse Practitioner and worked for over twenty years in various pediatric settings including pediatric intensive care, pediatric emergency and school nursing before joining the nursing faculty in 2003. She leads study abroad programs with students and volunteers as a nurse with immigrant families.

Mary A Dolansky, PhD, RN, FAAN, Associate Professor Department: Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing. Dr. Dolansky is the Sarah C. Hirsh Endowed Professor at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Director of the QSEN Institute and an Associate Professor at the School of Medicine. Case Western Reserve University (CWRU. She is the national advisor to the Veterans Administration Quality Scholars program and Senior Faculty at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Transforming Outpatient Primary Care. Dr. Dolansky is Director of the QSEN Institute (Quality and Safety Education for Nurses) an international community of healthcare providers providing resources for enhancing quality and safety competencies in both academia and practice. Her contributions to interprofessional quality improvement education include the massive open online course (MOOC) “Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality” that has reached over 15,000 interprofessional professionals across the world. Her area of research includes systems thinking and implementation science.

Shirley M Moore, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor Department: Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing. Dr. Shirley M. Moore is the Edward J. and Louise Mellen Professor of Nursing Emerita and Distinguished University Professor, Case Western Reserve University. She received her MSN and PhD from Case Western Reserve and has had a program of research focused on cardiovascular risk factor reduction. She s published more than 150 manuscripts and was named an inaugural inductee into the International Nurse Researcher Hall of Fame. She has served as co-director of U.S. Veterans Affairs Quality Scholars Program and past president of the Academy for Healthcare Improvement. Moore was named a fellow in the National Academies of Practice, the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Nursing, and has lead six national projects addressing the design and testing of interdisciplinary curricula on continuous quality improvement. She also works in leadership for the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) Institute at Case Western Reserve University.

Heather Bolden, M.Ed. Department: Teaching and Learning Technologies. Heather Bolden M.Ed. is the Lead Instructional Designer on University Technology's Teaching and Learning Technologies (UTech TLT) team at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU). Her leadership in Instructional Design has led to the creation of scalable processes as well as increased awareness, and use of, best practices in online and hybrid course design and development. She has worked with faculty from all nine CWRU academic units to design and develop engaging courses including Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs); academic and professional development online and hybrid courses; and standalone eLearning modules. Most relevant are her contributions to the project management, design, and development of the “Take the Lead on Healthcare Quality Improvement” MOOC and the eLearning modules created to educate MinuteClinic nurse practitioners on implementing Age-Friendly Health Systems into their practice.

Mamta K Singh, MD, MS, Professor Department: School of Medicine. Mamta K. Singh, MD, MS holds the Jerome Kowal, MD Designated Professor of Geriatric Health Education at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and is Associate Director for the VA Quality Scholars (VAQS) Program for the Northeast Ohio Healthcare System (Cleveland VA). She received her medical degree from UT Southwestern Medical School and has a masters in health services research from Case Western Reserve University. She has successfully developed assessment tools for system-based practice and practice-based learning improvement and published guidelines on QI education reporting She has multiple publications and has several CWRU school of medicine scholarship in teaching awards. She received the Wings of Excellence Award from the VA, the Clinician educator award from the Society of General Internal medicine and the Paul Batalden VAQS Alumni of the year award. Along with VA funding, she has successfully secured funding from the AMA, Macy foundation, RWJ foundation and HRSA.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics: This programme evaluation was determined as exempt by the Case Western Reserve University institutional review board (IRB-2014-891).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Case Western Reserve University as special funding for the development of massive open online courses awarded to authors Dolansky, Moore and Singh.

Contributor Information

Denice Reese, Professor of Nursing, Simulation Lab Coordinator, Davis and Elkins College, USA.

Mary A Dolansky, Sarah C. Hirsh Professor; Associate Professor, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, USA; Director, QSEN Institute; Senior Faculty Scholar, VA Quality Scholars Program.

Shirley M Moore, Edward J. and Louise Mellen Professor of Nursing and Associate Dean for Research, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, USA.

Heather Bolden, Teaching and Learning Designer, UTech Teaching and Learning Technologies, Case Western Reserve University, USA.

ORCID iDs

Mary A Dolansky https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6472-1275

Mamta K Singh https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8235-4272

References

- Artino AR., Jr (2012) Academic self-efficacy: From educational theory to instructional practice. Perspectives on Medical Education 1(2): 76–85. 10.1007/s40037-012-0012-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baernholdt M, Feldman M, Davis-Ajami ML, et al. (2019) An Interprofessional Quality Improvement Training Program that Improves Educational and Quality Outcomes. American Journal of Medical Quality Nov/Dec; 34(6): 577–584. DOI: 10.1177/1062860618825306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1977) Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84(2): 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Djukic M, Kovner CT, Brewer CS, et al. (2013. a) Early-career registered nurses’ participation in hospital quality improvement activities. Journal of Health Care Quality 28: 198–207. DOI: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31827c6c58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukic M, Kovner C, Brewer CS, et al. (2013. b) Improvements in educational preparedness for quality and safety. Journal of Nursing Regulation 4(2): 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dolansky MA, Moore SM. (2013) Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN): The key is systems thinking. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 18(3): 1.DOI: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol18No03Man01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolansky MA, Moore SM, Palmieri PA, et al. (2020) Development and validation of the systems thinking scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine. Epub ahead of print 27 April. 10.1007/s11606-020-05830-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dolansky M, Singh M, Neuhauser D. (2009) Quality and safety education: Foreground and background. Quality Management in Health Care 18: 151–157. DOI: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181aea292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding I, Klaas B, Yager JD, et al. (2013) Massive open online courses in public health. Frontiers in Public Health 1(59): 1–8. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory ME, Bryan JL, Hysong SJ, et al. (2018) Evaluation of a distance learning curriculum for interprofessional quality improvement leaders. American Journal of Medical Quality 33(6): 590–597. DOI: 10.1177/1062860618765661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess BJ, Johnston MM, Lynn LA, et al. (2013) Development of an instrument to evaluate residents’ confidence in quality improvement. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 39: 502–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2003) Health professions education: A bridge to quality, Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JT. (2013) A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. Journal of Patient Safety 9: 122–128. DOI: 110.1097/PTS.1090b1013e3182948a3182969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Fiordellisi W, Kuperman E, et al. (2018) X + Y = Time for QI: Meaningful engagement of residents in quality improvement during the ambulatory block. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 10(3): 316–324. DOI: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00761.1. See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29946390 (accessed 13 December 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K. (2014) Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 15(1): See http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1651 (accessed 13 December 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD. (2006) Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Kraiger K, Ford JK, Salas E. (1993) Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 311–328. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.311. [Google Scholar]

- Liyanagunawardena TR, Williams SA. (2014) Massive open online courses on health and medicine: Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 16(8): 1–24. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr J (2020) Remember the MOOCs? After near-death, they’re booming. The New York Times, 26 May 2020.

- Milligan C and Littlejohn A (2014) Supporting professional learning in a massive open online course. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 15(5). See http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1855 (accessed 13 December 2020).

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Moore SM, et al. (2012) Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care, 2nd edn. Oakbrook Terrace: The Joint Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Perna LW, Ruby A, Boruch RF, et al. (2014) Moving through MOOCs: Understanding the progression of users in massive open online courses. Educational Researcher 43(9): 421–432. DOI: 10.3102/0013189X14562423. [Google Scholar]

- Stathakarou N, Zary N, Kononowicz A. (2014) Beyond XMOOCs in healthcare education: Study of the feasibility in integrating virtual patient systems and MOOC platforms. PeerJ 2: e672.DOI: 10.7717/peerj.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Paquette L, Baker R. (2014) A Longitudinal Study on Learner Career Advancement in MOOCs. Journal of Learning Analytics 1(3): 203–206. See http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/JLA/article/view/4200/4438 (accessed 13 December 2020). [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014) Patient safety (updated June 2014). See http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/patient_safety/en/ (accessed 13 December 2020).

- Young JR (2020) Will COVID-19 Lead to Another MOOC Moment? 25 March 2020. EdSurge. See https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-03-25-will-covid-19-lead-to-another-mooc-moment?utm_content=buffer3685f&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=EdSurge (accessed 13 December 2020).