Abstract

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a multifactorial disease. Genetic predisposition and environmental triggers including infections are the major players of autoimmunity. We present a case of rheumatoid arthritis occurring after the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) infection.

Case presentation

A 72-year-old woman with a medical history of hypertension and atrial fibrillation presented for a 2-month history of bilateral symmetric polyarthritis starting 2 weeks after asymptomatic COVID-19 infection. Physical examination showed swelling and tenderness of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, wrists, and knees. She had increased inflammatory biomarkers (C-reactive protein:108 mg/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 95 mm, alpha-2 and gamma-globulins, interleukin 6: 16.5 pg/mL). Immunological tests revealed positive rheumatoid factor (128 UI/mL), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (200UI/mL), anti-nuclear antibodies (1:320), and anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG (12.24U/mL). She had the genotype: HLA-DRB1*04:11, HLA-DQB1*03:01, and HLA-DQB1* 03:02. Hands and feet radiographs did not show any erosion. Ultrasonography showed active synovitis and erosion of the 5th right metatarsal head. The diagnosis of RA was made. The patient received intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone (250 mg/day for 3 consecutive days) then oral corticosteroids (15 mg daily) and methotrexate (10 mg/week) were associated, leading to clinical and biological improvement.

Conclusion

Despite its rarity, physicians should be aware of the possibility of the occurrence of RA after COVID-19 infection. This finding highlights the autoimmune property of this emerging virus and raises further questions about the pathogenesis of immunological alterations.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, COVID-19, Immune dysregulation

1. Introduction:

Clinical manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may include fever, arthralgia, myalgia, respiratory and digestive symptoms, with varying degrees of severity [1].A syndrome of dysregulated immune overactivation may be associated, leading to several complications[2].Since its outbreak, many reports have been published suggesting the occurrence of immunological changes and autoimmunity[3].If musculoskeletal symptoms, such as non-specific arthralgia and myalgia, are frequent during COVID-19 infection, the risk of rheumatic diseases seems to be also increased after this infection[4].Rheumatologists stated that the low rate of acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine is alarming and should stir further interventions to reduce the levels of vaccine hesitancy [5]. Furthermore, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients faced remarkable difficulty to obtain their medications with subsequent change in their disease status. The challenges of the pandemic have hastened changes in the way health care is delivered [6]. We report the case of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) occurring after COVID-19 infection.

2. Case report

A 72-year-old woman with a body-massindex of 26 kg/m2 and a medical history of hypertension and atrial fibrillation, was diagnosed with asymptomatic COVID-19 infection. The diagnosis was confirmed by a positive nasopharyngeal swab by RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 that was performed as she had exposure to a confirmed case of COVID-19 (her husband). She received Azithromycin (500 mg orally daily the first day, followed by 250 mg daily for 4 days), paracetamol, vitamin D, C, and zinc supplementation. An informed consentwas obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Three months later, she presented to our departmentwith a 2-month history of inflammatory bilateral symmetric arthralgia of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, wrists, and knees. She had not received the COVID-19 vaccination. Examination revealed swellingand tenderness of the MCP, PIP joints and wrists with large effusion of the knees. There was no lymph node enlargement. Her body temperature was 37°. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory examinations showed increased inflammatory biomarkers: C-reactive protein (CRP) (108 mg/L, normal value (N): <8), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 95 mm/1st hr, alpha-2-globulins (14.5 g/L, N: 7.3–11), and gamma-globulins (18 g/L, N: 7.3–13.9). She had a high interleukin-6 (IL-6) level (16.5 pg/mL, N: <2). Blood cell count showed no cytopenia. Liver tests and renal function wereunremarkable.

Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) were positive at 128 UI/and 200UI/mL, respectively. Anti-nuclear antibodies were also positive at a titer of 1:320. Anti-ENA and anti-DNA were negative. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG was positive (12.24U/mL, ELIFA). The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II genotyping was performed and showed the presence of the alleles: HLA-DRB1*04:11, HLA-DQB1*03:01, and HLA-DQB1* 03:02.

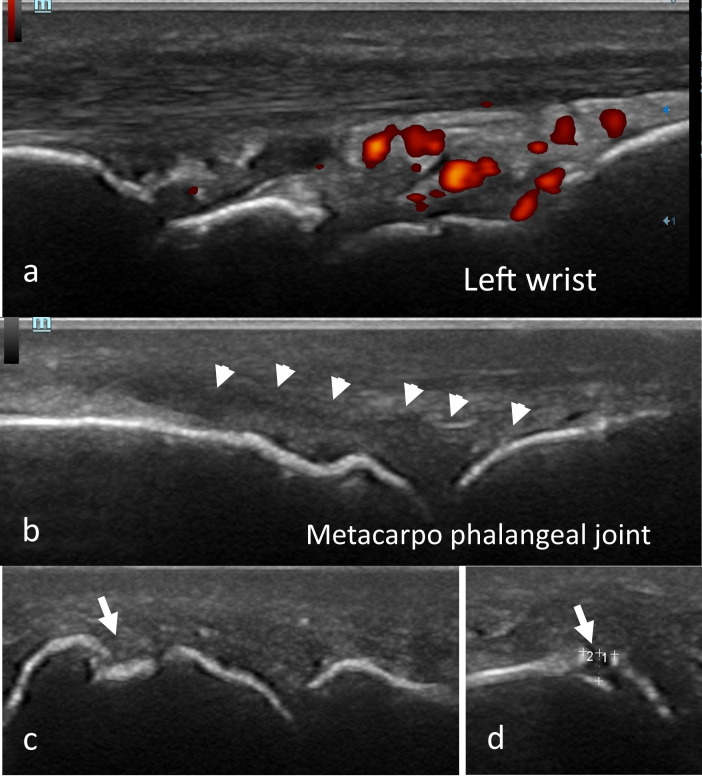

Hands and feet radiographs did not show any erosion. The chest radiograph was normal. Ultrasonography showed multiple active synovitisof the MCP, PIP, wrists, and knees. There was an erosion of the 5thright metatarsal head measuring 0.38×0.12 cm (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonography of the hands showing positive Doppler synovitis (grade 3) of the left wrist (a), synovitis of the metacarpophalangeal joint without Doppler signal (b) and erosion of the 5th right metatarsal head measuring 0.38×0.12 cm (c,d) in a 72-year-old woman.

The diagnosis of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made according to the 2010 American Congress of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) criteria[7].The patient received intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone (250 mg/day for 3 consecutive days). Then, methotrexate was initiated with a weekly dose of 10 mg associated with oral corticosteroids (prednisone 15 mg/day for 7 days then 10 mg daily).

During the follow-up, the IL-6 level has become within the normal range (4 pg/mL). The CRP level decreased at 16 mg/L and the ESR at 40 mm. The Disease activity score using ESR fell from 6.08 (high disease activity) to 4.2 (moderate disease activity) after a follow-up of 15 days.

3. Discussion

The pathogenesis of RA is multifactorial, including genetic, environmental, hormonal, and immunological factors. The HLA has been recognized as the strongest genetic risk factor for RA development accounting for 60% of genetic susceptibility. Indeed, HLA-DRB1 alleles (DRB1*0101, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0404, and DRB1*0405) are encountered in >80% of patients with RAand code for a sequence of amino-acids called the “shared epitope”. External factors such as smoking and infectionsinteract with this genetic background and contribute to an uncontrolled immune response and the production of ACPA[8].

It has been suggested that transient infection-dependent pathways contribute to the onset and perpetuation of this autoimmunity. It has been demonstrated that respiratory viral infections were associated with a higher number of incident RA. The parainfluenza, coronavirus, and metapneumovirus were the most implicated viruses in the occurrence of RA[9].We herein report a case of a 72-year-old womanwho presented withRA following a COVID-19 infection.

Emerging data showed that COVID-19 infection may induce autoimmunity. It has been reported to trigger numerous autoimmune diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, myelitis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia and vasculitis[4], [10].

In fact, SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to dysregulation of the immune system via three mechanisms: (i) molecular mimicry as a result of immunological similarities shared between the virus and self-antigens with cross-reactive immune response, (ii) activation of autoreactive immune T cells due to bystander activation, and (iii) persistent immune activation[11].Moreover, COVID-19 infection induces the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α) [2], particularly in severe cases. Besides, hyperinflammatory syndrome with immune over-reaction has been reported in patients with COVID-19 and was described as a cytokine storm[2].Furthermore, post-COVID-19 autoimmunity can also be explained by lymphopenia causing transient immunosuppression and loss of self-tolerance[12].

Table 1 summarizes 7 cases of RA occurring after COVID-19 infection [13], [14], [15], [16]. The infection severity varied from asymptomatic to critical form, suggesting no relationship between the COVID-19 severity and the risk of arthritis and autoimmunity. In the present case, arthritis occurred in a 72-year old woman, 15 days after an asymptomatic COVID-19 infection with elevated inflammatory biomarkers and positive RF and ACPA. Our patient was genetically predisposed to RA with the genotype HLA-DRB1*04:11, HLA-DQB1*03:01, and HLA-DQB1* 03:02.COVID-19 infection acted therefore as an environmental trigger. However, Perrot et al. reported a case of RA following COVID-19 infection, occurring in a patient without genetic predisposition[14]. Although COVID-19 is not yet considered as a trigger for RA it has been suggested as a risk factor for inducing a flare [15]. The management of RA post COVID-19 did not differ from other RA. In our case, methotrexate and steroids lead to the alleviation of clinical and biological parameters.

Table 1.

Cases of acute arthritis following corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection.

| Reference | Age (y)/sex | COVID-19 infection severity* | Duration till arthritis (days) | Involved joints | Inflammatory Biomarkers | Immune profile (RF, ACPA, ANA) | HLA genotyping | Arthritis management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derksen et al. [13] | 67/male | Moderate to severe | Already present | small/large | ESR: 36 mm/1st hr CRP: 6 mg/L |

N.S | N.S | N.S |

| 49/male | 42 | small/large | ESR: 79 mm/1st hr CRP: 449 mg/L |

N.S | N.S | N.S | ||

| 67/female | 98 | small | ESR: 49 mm/1st hr CRP: 168 mg/L | N.S | N.S | N.S | ||

| 65/male | 3 | small/large | ESR: 26 mm/1st hr CRP: 6 mg/L |

N.S | N.S | N.S | ||

| Perrot et al. [14] | 60/female | Mild | 25 | MCP/IP | CRP: 18.5 mg/L IL-6: 31 pg/mL |

Positive ACPA, ANA, anti-SSA/SSB, anti-DNA. Negative RF |

No classic HLA genotype† |

Methotrexate (10 mg/w) |

| Baimukhamedov et al. [15] | 67/male | Severe | 37 | Knees/hands | ESR: 59 mm/1st hr CRP: 55 mg/L |

RF: 411 IU/ml ACPA§: 104 IU/ml |

N.S | Methotrexate (15 mg/w) Methylprednisolone (8 mg/d) |

| Roongta et al. [16] | 56/female | Severe | 14 | Knees/wrists | Elevated CRP and ESR | RF§: 131 IU/mL ACPA§: 35 IU/ml |

N.S | Methotrexate (15 mg/w) |

| This case | 72/female | Asympt-omatic | 15 | MCP/PIP/wrists/knees | ESR: 95 mm/1st hr CRP: 108 mg/L Increased α-2 and γ-globulins IL-6: 16.5 pg/mL |

RF: 128 ACPA:200 ANA: 1:320 |

DRB1*04:11, DQB1*03:01, DQB1* 03:02. | Methotrexate (10 mg/w) Steroids |

RF: rheumatoid factor, ACPA: anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, ANA: antinuclear antibodies, NS: not specified, MCP: metacarpophalangeal, IP: interphalangeal, PIP: proximal IP, HLA: Human Leukocyte Antigen, CRP: C-reactive protein, ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate. * Symptoms of COVID-19 infection were collected and severity was classified as 4 levels: mild, moderate, severe, and critical.

†:HLA-A*01:01, HLA-A*02:01; HLA-B*08:01, HLA-B*1402; HLA-C*07:01, HLA-C*08:02; HLA-DRB1*15:01, HLA-DRB1*--; HLA-DQB1*06:02, HLA-DQB1*--. §: initially negative. ¶: From the five cases of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) reported by Derksen et al, we included the four cases of new-onset RA. One patient was excluded because he had a history of RA prior to COVID-19 infection.

In conclusion, despite its rarity, physicians should be aware of the possibility of the occurrence of RA after COVID-19 infection. This finding highlights the autoimmune property of this emerging virus and raises further questions about the pathogenesis of immunological alterations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maroua Slouma: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Takoua Mhemli: Writing – original draft. Maissa Abbes: Writing – review & editing. Wafa Triki: Data curation. Rim Dhahri: Data curation, Formal analysis. Leila Metoui: Conceptualization. Imen Gharsallah: Visualization. Bassem Louzir: Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Egyptian Society of Rheumatic Diseases.

References

- 1.Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y.u., Liang W.-H., Ou C.-Q., He J.-X., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melenotte C., Silvin A., Goubet A.-G., Lahmar I., Dubuisson A., Zumla A., et al. Immune responses during COVID-19 infection. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1) doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1807836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingraham N.E., Lotfi-Emran S., Thielen B.K., Techar K., Morris R.S., Holtan S.G., et al. Immunomodulation in COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):544–546. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30226-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assar S., Pournazari M., Soufivand P., Mohamadzadeh D. Systemic lupus erythematosus after coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) infection: Case-based review. EgyptRheumatol. 2022;44(2):145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejr.2021.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammam N., Tharwat S., Shereef R.R.E., Elsaman A.M., Khalil N.M., Fathi H.M., et al. Egyptian College of Rheumatology (ECR) COVID-19 Study Group. Rheumatology university faculty opinion on coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) vaccines: the vaXurvey study from Egypt. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(9):1607–1616. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04941-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abualfadl E., Ismail F., Shereef R.R.E., Hassan E., Tharwat S., Mohamed E.F., et al. ECR COVID19-Study Group. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on rheumatoid arthritis from a Multi-Centre patient-reported questionnaire survey: influence of gender, rural-urban gap and north-south gradient. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(2):345–353. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04736-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aletaha D., Neogi T., Silman A.J., Funovits J., Felson D.T., Bingham C.O., et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yap H.Y., Tee S.Z., Wong M.M., Chow S.K., Peh S.C., Teow S.Y. Pathogenic Role of Immune Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Implications in Clinical Treatment and Biomarker Development. Cells. 2018;7(10):161. doi: 10.3390/cells7100161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joo Y.B., Lim Y.H., Kim K.J., Park K.S., Park Y.J. Respiratory viral infections and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assar S., Pournazari M., Soufivand P., Mohamadzadeh D., Sanaee S. Microscopic polyangiitis associated with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) infection in an elderly male. Egypt Rheumatol. 2021;43(3):225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ejr.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah S., Danda D., Kavadichanda C., Das S., Adarsh M.B., Negi V.S. Autoimmune and rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its treatment. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(10):1539–1554. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04639-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cañas C.A. The triggering of post-COVID-19 autoimmunity phenomena could be associated with both transient immunosuppression and an inappropriate form of immune reconstitution in susceptible individuals. Med Hypotheses. 2020;145:110345. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derksen V.F.A.M., Kissel T., Lamers-Karnebeek F.B.G., van der Bijl A.E., Venhuizen A.C., Huizinga T.W.J., et al. Onset of rheumatoid arthritis after COVID-19: coincidence or connected? Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(8):1096–1098. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perrot L., Hemon M., Busnel J.-M., Muis-Pistor O., Picard C., Zandotti C., et al. First flare of ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(1):e6–e8. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baimukhamedov C., Barskova T., Matucci-Cerinic M. Arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(5):e324–e325. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roongta R., Chattopadhyay A., Ghosh A. Correspondence on 'Onset of rheumatoid arthritis after COVID-19: coincidence or connected?'. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;epub doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220479. ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]