Abstract

Background

Job burnout is more prevalent among nurses than other medical team members and may have adverse effects on the mental and physical health of both nurses and their patients.

Aims

To evaluate the associations between job burnout as a dependent variable with perceived stress and self-compassion as independent variables, and test the buffering role of self-compassion in the link between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study with a convenience sampling method. A total of 150 nurses from four hospitals in Tehran, Iran participated in this study and completed three questionnaires, namely the Perceived Stress Scale, the Self-Compassion Scale and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory.

Results

Partial least square-structural equation modelling showed greater levels of perceived stress associated with greater levels of job burnout (β = 0.795, p < 0.001), and greater levels of self-compassion associated with lower levels of job burnout (β = –0.512, p < 0.001) in nurses. The results of the interaction-moderation analysis showed that self-compassion diminished the effect of perceived stress on job burnout in nurses.

Conclusions

The results of this study not only showed a significant association between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses, but also increased our understanding about the buffering role of self-compassion in the link between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses.

Keywords: burnout, nurses, partial least square, self-compassion, stress, SEM

Introduction

Nurses experience higher levels of job burnout than other healthcare workers (Arnetz et al., 2019; Kelly et al., 2019; Xian et al., 2020), and indicate greater absenteeism and intentions to leave their work (Dreison et al., 2018; Morse et al., 2012). Nurses hold one of the most essential positions in a successful and functional healthcare system, and job burnout among nurses may have adverse effects for both their mental and physical health and the treatment process of patients (Lee and Wang, 2002). Job burnout is defined as a set of symptoms including emotional exhaustion associated with a lack of energy, and negative attitudes to one’s self, patients, colleagues and organisations (Cieslak et al., 2008). In addition to workplace facilities, psychological factors can also affect nurses’ burnout. Given the importance of job burnout in nurses, this study aims to investigate the relationships between perceived stress and self-compassion with job burnout, and to examine the role of self-compassion as a moderator in the relationship between stress and job burnout in nurses.

Perceived stress has the greatest influence on nurses’ burnout compared to any other factor (Akintola et al., 2013). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) define perceived stress as a person’s reaction to an environment that is perceived as a threat to his or her abilities and health. The term perceived stress refers to how a person feels about stress, not just measurable stress itself. Therefore, the perception of a stressful situation is more important than objective measures of the stressors and can influence a person’s performance (Abdollahi et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2020). Among members of the medical team, nurses experience high levels of stress (Clouston, 2019). For example, they may engage in more work-related stressors, such as long work hours, lack sufficient staff to patient care, be physically or verbally abused by patients and their relatives, be emotionally affected by the death of patients, experience conflict with other medical team members, and lack necessary financial and emotional support (Faraji et al., 2012; Purcell et al., 2011). Studies have also shown that nursing holds the number one position amongst the 40 most stressful jobs (Freshwater and Cahill, 2010; Raiger, 2005). Additionally, 7.4% of nurses are absent during the week due to exhaustion, disability, or stress, which is 80% more than other jobs (Raiger, 2005). In Iran, more than 75% of nurses suffer from stress, depression and other mental problems that have a detrimental effect on their own and their patients’ lives (Aghilinejad et al., 2010). The relationship between stress and burnout in nurses has been investigated in several studies (Dev et al., 2020; Kim, 2020; Montanari et al., 2019; Pérula-de Torres et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). However, limited studies have shown a relationship between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses (Divinakumar et al., 2014; Mahon et al., 2017; Munnangi et al., 2018), and the relationship between perceived stress and burnout has not been studied among Iranian nurses. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the relationship between perceived stress and job burnout in Iranian nurses, and to examine self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between perceived stress and job burnout.

According to the transactional-cognitive model of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), there are individual differences between individuals’ perceptions and reactions to stressful situations. In other words, a particular situation (e.g. working long hours) can be perceived as stressful for one person but not another. Therefore, the process of psychological evaluation has a great impact on the evaluation and reaction to stressors. Self-compassion is one of the psychological factors that may play a moderating role between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses (Dev et al., 2020). Self-compassion is comprised of three essential components: (a) self-kindness, defined as understanding one’s self without having a judgmental or self-critical view of suffering; (b) common humanity, defined as an accepting of one’s individual experiences as part of the experiences of human beings; and (c) mindfulness, defined as accepting one’s own emotions without exaggeration (Neff, 2016).

Research has supported the positive relationships between self-compassion and optimism (Imtiaz and Kamal, 2016), positive emotion (Choi et al., 2014), and positive psychological function (Neff et al., 2007). Additionally, studies have supported the inverse relationships between self-compassion with work stress (Dev et al., 2020), stress (Abdollahi et al., 2020b), self-criticism, perfectionism, depression (Abdollahi et al., 2020a), and rumination (Imtiaz and Kamal, 2016). Self-compassion maintains an individual’s positive mental health by integrating emotional regulation and providing effective strategies to protect themselves from stressors (Dev et al., 2018; Gilbert, 2009). Empirical evidence suggests that self-compassion plays a moderating role between negative psychological constructs and physical and mental health outcomes (Krieger et al., 2015; Kyeong, 2013; Williamson, 2020). A cross-sectional study by Lathren and colleages (2019) demonstrated that higher levels of self-compassion in a sample of US adolescents was associated with lower levels of perceived stress and lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Likewise, a cross-sectional study of nurses at a New Zealand hospital showed that higher levels of self-compassion was associated with lower levels of work-related stress and job burnout and higher levels of quality of life (Dev et al., 2020). Experimental and theoretical support for self-compassion along with empathy, acceptance and kindness, are essential concepts that could reduce the effects of perceived stress and are likely to have negative effects on job burnout (Dev et al., 2018; Neff et al., 2007). In this study, we sought to increase the empirical evidence of the benefits of self-compassion in nurses by examining whether self-compassion could moderate the relationship between perceived stress and job burnout. Therefore, we hypothesised that higher levels of perceived stress would be positively associated with higher levels of job burnout, higher levels of self-compassion would be negatively associated with lower levels of job burnout, and self-compassion would moderate the relationship between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a cross-sectional study. G-Power version 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009) indicated a sample size of 150 would be needed for a small effect size, with 80% power and 5% significance level. A total of 150 nurses were recruited by convenience sampling method (110 females, Mage = 34.12 years, SDage = 4.2, rangeage = 24–51) from four public hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Inclusion criteria were a minimum of six months nursing experience and full-time nurses. About 96% (n = 144) of nurses were married and 60% (n = 90) had children. About 96% (n = 144) of them worked full time at the hospital. Regarding education, 20% (n = 30) had a diploma, 22% (n = 33) held an associate’s degree, 40% (n = 60) had a bachelor’s degree, and 18% (n = 27) held a master’s degree in nursing. Table 1 shows the number of nurses working in different units of the hospital.

Table 1.

Nurses’ roles in different hospital units.

| Units | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency room | 24 | 16 |

| Intensive care | 12 | 8 |

| Medical/surgical | 54 | 36 |

| Paediatrics | 8 | 5 |

| Maternity/obstetrics | 22 | 15 |

| Psychiatric/mental health | 18 | 12 |

| Operating room/post-operative care | 12 | 8 |

Procedure

The research process was studied and approved by the ethics committee of Alzahra University. Questionnaires were distributed to participating nurses after they signed a consent form, and permission to complete questionnaires was obtained from hospital heads and hospital unit managers. The data collection took about two months, from May to July 2018. Participants completed the questionnaires in about 20 minutes. Of the 160 questionnaires distributed among nurses, 155 were returned to the researchers and five were excluded because of incompleteness, yielding 150 complete questionnaires.

Measures

The Self-Compassion Scale

This measure was developed by Neff (2003) and is comprised of 24 items on a five-point Likert-type scale that assesses six interrelated components of self-compassion: kindness with self; self-judgment; mindfulness; over-identification; common humanity; and isolation. The sum of the six components evaluates the participant’s self-compassion concept, and scores range from 24 to 120. An example item for kindness is ‘When I’m going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need’. Higher scores obtained on the Self-Compassion Scale by respondents indicate higher levels of self-compassion. In a previous Iranian study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.83 (Abdollahi et al., 2020b).

Perceived Stress Scale

This measure was developed by Cohen and colleagues (1983) and is comprised of 10 items on a five-point Likert-type scale (0 = Never to 4 = Very often) that assesses perceived stress in nurses within the past month. This scale has a priority for measuring perceived stress compared to other scales, such as the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (Levenstein et al., 1993), because in addition to the English version, this scale has been validated in 25 languages and is used in most studies (Lee, 2012). An example item is ‘In the last month, how often have you felt that you had everything under control?’. The total scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. In a previous Iranian study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.81 (Abdollahi et al., 2014).

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI)

This measure was developed by Kristensen and colleagues (2005) and is comprised of 19 items on a five-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = Never to 5 = Always) that assesses three interrelated components of burnout, namely, personal burnout, work-related burnout and client-related burnout. The CBI has a priority for measuring burnout over other scales, such as the Meier Burnout Assessment (MBA; Meier, 1984), because the MBA assesses three different types of burnout (reinforcement expectations, outcome expectations and efficacy expectations) and the CBI assesses three interrelated components of burnout (Kristensen et al., 2005). An example item is ‘Is your work emotionally exhausting?’. The sum of the three components evaluates burnout concept in nurses. The total scores range from 19 to 95, with higher scores indicating higher levels of burnout. The Iranian version of the CBI was used in this study and had a good internal consistency (Javanshir et al., 2019).

Statistical method

To analyse the data in this study, variance-based structural equation modelling, supported by SmartPLS 3 software (version 3.2.3) was employed (Ringle et al., 2015). The advantages of the partial least square method are that it is suitable for analysing the proposed model with a small sample size, has an insensitivity to data normality, is proficient at analysing complex path models, and allows for conducting moderation analyses (Sarstedt et al., 2018).

Prior to using the SmartPLS 3 software for analyses, the amount of missing data was estimated in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 24) software. The rate of missing data for items was less than 2%, and missing data were addressed by the regression imputation method.

Results

Measurement model

At the measurement model stage, the convergent validity, reliability and discriminant validity should be estimated (Hair et al., 2014). Convergent validity and reliability were measured by the value of factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha. The results showed the factor loadings were above 0.50 and no items were eliminated. The results indicated that there was an acceptable convergent validity among the items of each research variable. The results also showed that the values of AVE, CR and Cronbach’s alpha were greater than 0.50, 0.70, and 0.70 respectively (Hair et al., 2014), indicating acceptable convergent validity for the research variables (see Table 2). Discriminant validity and multicollinearity were measured by the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) and the variance inflation factor (VIF) respectively. If the value of the HTMT was less than 0.85, and the VIF was less than 5.0 (Henseler et al., 2015), this signifies acceptable discriminant validity. The results of both criteria showed that the variables had satisfactory discriminant validity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Values of composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), variance inflation factor (VIF), mean and standard deviation.

| Variable | Cronbach’s alpha | CR | AVE | HTMT | VIF | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.6 | 0.74 | 1.87 | 75 | 5.32 |

| Perceived stress | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.5 | 0.72 | 1.76 | 24 | 4.23 |

| Burnout | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.6 | 0.75 | 1.52 | 66 | 5.19 |

Structural model

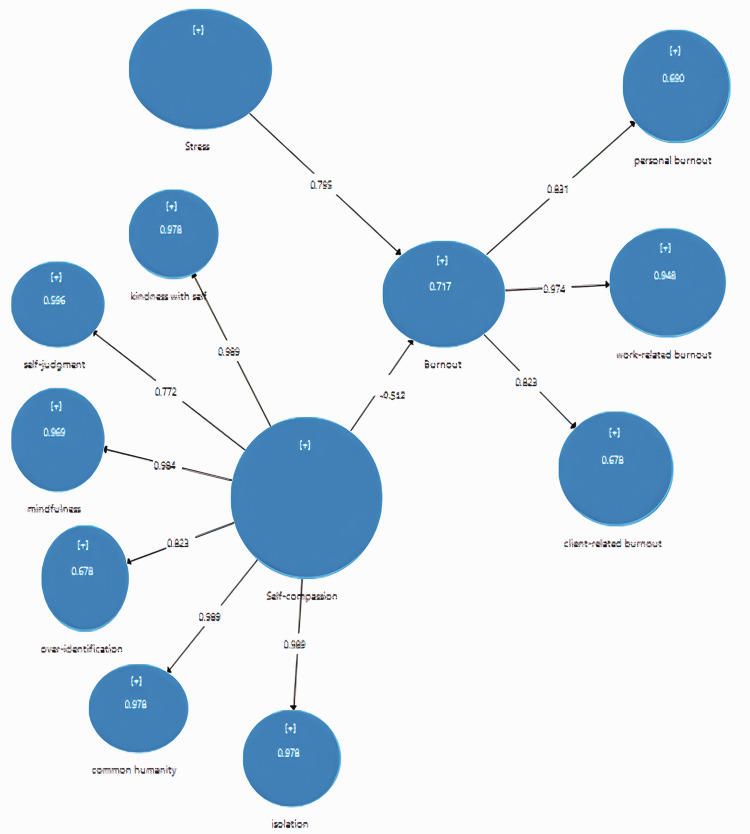

At the structural model stage, the research hypotheses, coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and Stone–Geisser (Q2) values were evaluated. The structural model results showed a significant positive association between perceived stress and burnout (β = 0.795, t = 8.75, p < 0.001), and a significant negative association between self-compassion and burnout (β = –0.512, t = 4.75, p < 0.001; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural model for burnout in nurses.

R2 was calculated to estimate the value of variance in job burnout explained by perceived stress and self-compassion. An R2 value exceeding 0.67 is considered a high coefficient of determination (Henseler et al., 2015). R2 for job burnout as an endogenous variable was 0.717, indicating that perceived stress and self-compassion explained 71.7% of the changes in nurses’ burnout. To calculate the extent to which deletion of exogenous variables (perceived stress and self-compassion) could impact the endogenous variable (job burnout) f2 was used. Cohen (1988) classified f2 as small, medium and large when the values are 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 respectively. For perceived stress and self-compassion, f2 was 0.42 and 0.38 respectively, indicating large effect sizes to explain job burnout. Q2 was used to calculate predictive relevance of the endogenous variable (job burnout). Henseler and colleagues (2015) classified Q2 as small, medium and large when the values are 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 respectively. The result showed that the value of Q2 was 0.39, indicating large predictive relevance of nurses’ job burnout.

Moderating effect of self-compassion

The interaction-moderation method in Smart-PLS 3 software was recruited to test the moderating role of self-compassion in the link between perceived stress and job burnout. The interaction-moderation results revealed that there was a significant positive relationship between perceived stress with job burnout (β = 0.795, t = 8.75, p < 0.001) and a negative significant relationship between self-compassion and job burnout (β = –0.512, t = 4.75, p < 0.001). The interaction effect of self-compassion and perceived stress had a negative and significant relationship with job burnout (β = –0.165, t = 3.61, p < 0.001). Thus, self-compassion played a buffering role in the link between perceived stress and burnout in nurses.

Discussion

The result of the analysis by the PLS-SEM is in line with prior studies (Divinakumar et al., 2014; Munnangi et al., 2018) that showed higher levels of perceived stress were associated with higher levels of job burnout in nurses from India and the USA; the present study supports the previous result among Iranian nurses. The cognitive-transactional stress theory (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) provides a descriptive interpretation for this finding, meaning that an individual’s perception of the events may impact their coping skills and behaviour. For example, if a nurse has stressful beliefs about a situation and perceives the situation as terrifying, unchangeable and uncontrollable, it is likely that the nurse’s negative perceived stress may lead to job burnout. On the other hand, if the nurse has positive beliefs in the face of the situation, the nurse is more likely to find the situation controllable, changeable and an opportunity to learn, and may be less likely to experience job burnout.

The next finding showed that higher levels of self-compassion were associated with lower levels of job burnout in nurses, which was in line with past studies (Dev et al., 2018, 2020). A descriptive clarification of this finding is that individuals with high levels of self-compassion are more likely to have calming, soothing, kind and compassionate responses to stressful situations rather than overly critical and harsh responses. They also have a greater ability to dispense unhelpful thoughts, accept shortcomings in themselves and others, and are able to manage themselves kindly in stressful situations (Abdollahi et al., 2020b; Ferrari et al., 2018). Therefore, individuals with such characteristics are less likely to experience job burnout. Conversely, individuals with low levels of self-compassion are more likely to exhibit self-criticism, self-blame, reduced empathy, exhaustion, emotional numbing and a lack of supportive social interactions (Montero-Marin et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that individuals with such characteristics are at risk of developing burnout.

The interaction-moderation analysis demonstrated that self-compassion mitigates the effect of perceived stress on job burnout in nurses. A potential clarification for the moderating role of self-compassion is that individuals with greater self-compassion possess characteristics such as self-kindness in stressful situations, acceptance of situations without negative emotions, acceptance of one’s own and other’s deficits without judgment, strength of positive emotions and thoughts in themselves, and forgiveness in self and others (Neff et al., 2007). Therefore, the valuable attributes of self-compassion could be a protective factor against perceived stress and reduce the likelihood of job burnout in nurses.

Implications of the present study

This study showed that perceived stress had a positive association, and self-compassion had a negative association, with job burnout in nurses. Therefore, when mental health professionals assess nurses’ job burnout, it is essential to assess perceived stress and self-compassion. The results of this study also showed that self-compassion could reduce the effects of perceived stress and decrease the likelihood of job burnout in nurses. Although the nature of this study is not empirical, it could be deduced that by improving the characteristics of self-compassion in nurses, their levels of perceived stress and job burnout would decrease.

Limitations and recommendations

Some of the limitations of the current study include a small sample size, self-reported data collection and using a cross-sectional method. It is recommended that future studies recruit larger sample sizes, employ the longitudinal method, and use other data collection methods, such as interviewing and observation. In this study, due to the unequal sample size between the male and female group, a variance analysis for gender was impossible for the proposed model. Future studies are recommended to perform a variance analysis for gender on the proposed model by taking into account approximately equal sample sizes between males and females. The study sample focused only on nurses, and other members of the medical staff were not included. It is recommended for future studies to find out whether there are differences between the nurse group and other healthcare member groups in the proposed model.

In addition to the significant association found between perceived stress and job burnout, the present study provided a deeper understanding of the role of self-compassion as a moderator between perceived stress and job burnout in nurses which has implications for training programmes and professional development. Self-compassion training, which includes self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness, could reduce the adverse effects of emotional, psychological and physical burnout in nurses.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Job burnout is a prevalent phenomenon that may have adverse effects on the mental and physical health of nurses and their patients.

Perceived stress was positively associated with job burnout and self-compassion was negatively associated with job burnout in nurses.

The results showed that self-compassion diminished the effect of perceived stress on job burnout in nurses, and this may impact the quality of care given to patients.

Self-compassion training could reduce the adverse effects of emotional, psychological, and physical burnout in nurses.

Biography

Abbas Abdollahi is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Counselling in the Faculty of Education and Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

Azadeh Taheri is a PhD student in counselling in the Department of Counselling in the Faculty of Education and Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

Kelly A. Allen is an Educational and Developmental Psychologist and Senior Lecturer at Monash University.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics: The research process was studied and approved by the ethics committee of Alzahra University. Reference number 111399.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Abbas Abdollahi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8346-5043.

Contributor Information

Abbas Abdollahi, Assistant Professor, Department of Counselling, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

Azadeh Taheri, PhD Student, Department of Counselling, Alzahra University, Iran.

References

- Abdollahi A, Abu Talib M, Yaacob SN, et al. (2014) Hardiness as a mediator between perceived stress and happiness in nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 21(9): 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi A, Allen KA, Taheri A. (2020. a) Moderating the role of self-compassion in the relationship between perfectionism and depression. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi A, Taheri A, Allen KA. (2020. b) Self‐compassion moderates the perceived stress and self‐care behaviors link in women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 29: 927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghilinejad M, Attarchi MS, Golabadi M, et al. (2010) Comparing stress level of woman nurses of different units of Iran university hospitals in autumn 2009. Annals of Military and Health Sciences Research 8: 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Akintola O, Hlengwa WM, Dageid W. (2013) Perceived stress and burnout among volunteer caregivers working in AIDS care in South Africa. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69(12): 2738–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz J, Sudan S, Goetz C, et al. (2019) Nurse work environment and stress biomarkers: Possible implications for patient outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 61(8): 676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YM, Lee DG, Lee H-K. (2014) The effect of self-compassion on emotions when experiencing a sense of inferiority across comparison situations. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 114(1): 949–953. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak R, Korczynska J, Strelau J, et al. (2008) Burnout predictors among prison officers: The moderating effect of temperamental endurance. Personality and Individual Differences 45(7): 666–672. [Google Scholar]

- Clouston TJ. (2019) Pearls of wisdom: Using the single case study or ‘gem’ to identify strategies for mediating stress and work-life imbalance in healthcare staff. Journal of Research in Nursing 24(1–2): 61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24(4): 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev V, Fernando AT, Consedine NS. (2020) Self-compassion as a stress moderator: A cross-sectional study of 1700 doctors, nurses, and medical students. Mindfulness 11: 1170–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev V, Fernando AT, Lim AG, et al. (2018) Does self-compassion mitigate the relationship between burnout and barriers to compassion? A cross-sectional quantitative study of 799 nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies 81: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divinakumar KJ, Pookala SB, Das RC. (2014) Perceived stress, psychological well-being and burnout among female nurses working in government hospitals. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2(4): 1511–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Dreison KC, Luther L, Bonfils KA, et al. (2018) Job burnout in mental health providers: A meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 23(1): 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraji O, Valiee S, Moridi G, et al. (2012) Relationship between job characteristic and job stress in nurses of kurdistan university of medical sciences educational hospitals. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research 7(25): 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. (2009) Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods 41(4): 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Yap K, Scott N, et al. (2018) Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLoS ONE 13(2): 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freshwater D, Cahill J. (2010) Care and compromise: Developing a conceptual framework for work-related stress. Journal of Research in Nursing 15(2): 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. (2009) Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 15(3): 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Jr, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, et al. (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review 26(2): 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(1): 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Imtiaz S, Kamal A. (2016) Rumination, optimism, and psychological well-being among the elderly: self-compassion as a predictor. Journal of Behavioural Sciences 26(1): 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Javanshir E, Dianat I, Asghari-Jafarabadi M. (2019) Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory. Health Promotion Perspectives 9(2): 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly LA, Lefton C, Fischer SA. (2019) Nurse leader burnout, satisfaction, and work-life balance. Journal of Nursing Administration 49(9): 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. (2020) Emotional labor strategies, stress, and burnout among hospital nurses: A path analysis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 52(1): 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger T, Hermann H, Zimmermann J, et al. (2015) Associations of self-compassion and global self-esteem with positive and negative affect and stress reactivity in daily life: Findings from a smart phone study. Personality and Individual Differences 87: 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, et al. (2005) The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress 19(3): 192–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kyeong LW. (2013) Self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between academic burn-out and psychological health in Korean cyber university students. Personality and Individual Differences 54(8): 899–902. [Google Scholar]

- Lathren C, Bluth K, Park J. (2019) Adolescent self-compassion moderates the relationship between perceived stress and internalizing symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences 143: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH. (2012) Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research 6(4): 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Wang H. (2002) Occupational stress and related factor in public health nurses. Journal of Nursing Research 10(4): 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. (1993) Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 37(1): 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon MA, Mee L, Brett D, et al. (2017) Nurses’ perceived stress and compassion following a mindfulness meditation and self compassion training. Journal of Research in Nursing 22(8): 572–583. [Google Scholar]

- Meier ST. (1984) The construct validity of burnout. Journal of Occupational Psychology 57(3): 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari KM, Bowe CL, Chesak SS, et al. (2019) Mindfulness: Assessing the feasibility of a pilot intervention to reduce stress and burnout. Journal of Holistic Nursing 37(2): 175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Marin J, Zubiaga F, Cereceda M, et al. (2020) Correction. Burnout subtypes and absence of self-compassion in primary healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study. Plos One 15(4): e0231370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. (2012) Burnout in mental health services: A review of the problem and its remediation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 39(5): 341–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnangi S, Dupiton L, Boutin A, et al. (2018) Burnout, perceived stress, and job satisfaction among trauma nurses at a level I safety-net trauma center. Journal of Trauma Nursing 25(1): 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. (2003) Self and identity the development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity 2(3): 223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. (2016) The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness 7(1): 264–274. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick KL. (2007) An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality 41(4): 908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Pérula-de Torres L-A, Atalaya JCV-M, García-Campayo J, et al. (2019) Controlled clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of a mindfulness and self-compassion 4-session programme versus an 8-session programme to reduce work stress and burnout in family and community medicine physicians and nurses: MINDUUDD study protocol. BMC Family Practice 20(1): 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SR, Kutash M, Cobb S. (2011) The relationship between nurses’ stress and nurse staffing factors in a hospital setting. Journal of Nursing Management 19(6): 714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiger J. (2005) Applying a cultural lens to the concept of burnout. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 16(1): 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringle CM, Wende S and Becker J-M (2015) SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. Available from: http://www.smartpls.com.

- Sarstedt M, Bengart P, Shaltoni AM, et al. (2018) The use of sampling methods in advertising research: A gap between theory and practice. International Journal of Advertising 37(4): 650–663. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Okoli CTC, He H, et al. (2020) Factors associated with compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 102: 103472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J. (2020) Effects of a self-compassion break induction on self-reported stress, self-compassion, and depressed mood. Psychological Reports 123: 1537–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian M, Zhai H, Xiong Y, et al. (2020) The role of work resources between job demands and burnout in male nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29(3–4): 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]