Abstract

Background

Telehealth approaches are increasingly being used to support patients with advanced diseases, including cancer. Evidence suggests that telehealth is acceptable to most patients; however, the extent of and factors influencing patient engagement remain unclear.

Objective

The aim of this review is to characterize the extent of engagement with telehealth interventions in patients with advanced, incurable cancer reported in the international literature.

Methods

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) and is reported in line with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 guidelines. A comprehensive search of databases was undertaken for telehealth interventions (communication between a patient with advanced cancer and their health professional via telehealth technologies), including MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science, from the inception of each electronic database up until December 31, 2020. A narrative synthesis was conducted to outline the design, population, and context of the studies. A conceptual framework of digital engagement comprising quantitative behavioral measures (frequency, amount, duration, and depth of use) framed the analysis of engagement with telehealth approaches. Frequency data were transformed to a percentage (actual patient engagement as a proportion of intended engagement), and the interventions were characterized by intensity (high, medium, and low intended engagement) and mode of delivery for standardized comparisons across studies.

Results

Of the 19,676 identified papers, 40 (0.2%) papers covering 39 different studies were eligible for inclusion, dominated by US studies (22/39, 56%), with most being research studies (26/39, 67%). The most commonly reported measure of engagement was frequency (36/39, 92%), with substantial heterogeneity in the way in which it was measured. A standardized percentage of actual patient engagement was derived from 17 studies (17/39, 44%; n=1255), ranging from 51% to 100% with a weighted average of 75.4% (SD 15.8%). A directly proportional relationship was found between intervention intensity and actual patient engagement. Higher engagement occurred when a tablet, computer, or smartphone app was the mode of delivery.

Conclusions

Understanding engagement for people with advanced cancer can guide the development of telehealth approaches from their design to monitoring as part of routine care. With increasing telehealth use, the development of meaningful and context- and condition-appropriate measures of telehealth engagement is needed to address the current heterogeneity in reporting while improving the understanding of optimal implementation of telehealth for oncology and palliative care.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) CRD42018117232; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018117232

Keywords: systematic review, advanced cancer, engagement, digital health, telehealth, mobile phone

Introduction

Background

Cancer ranks as a leading cause of death worldwide and is a leading cause of premature death in most countries [1]. For people living with advanced cancer, fluctuating unmet needs can be experienced over time with disease progression [2]. Common symptoms include pain, experienced in approximately two-thirds (66.4%) of patients with advanced disease [3], alongside breathlessness, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue [4]. Typically, individuals experience more than one symptom, with an average of 14 symptoms for those with advanced cancer [5]. Such physical symptoms often exist alongside deterioration across physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and overall quality of life (QOL) trajectories [6]. There remain gaps in supporting care delivery for patients with cancer, including barriers in health communication with health care providers, lack of care coordination, and challenges in accessing care [7].

Telehealth and telehealth interventions refer to a method in which the patient and health care professional can communicate clinical information remotely via a number of different mediums such as telephone, web-based methods, and mobile apps [8]. This method is increasingly used to deliver cancer care as it provides opportunities for efficient and flexible service delivery and enables clinicians to maintain involvement independent of the physical location of the patients or clinicians [9-12]. These characteristics have also driven their increased application to support delivery of care during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling avoidance of direct physical contact while contributing to provision of continuous care in the community. Telephone-based approaches have been highlighted as a possible means of overcoming gaps in service delivery for patients with cancer [7], including reducing the travel required to access support services that can lead to physical, psychological, and financial stress [13,14]. Examination of telehealth approaches for patients with chronic diseases has found varying effects, with improved self-management of diabetes and reduced mortality and hospital admissions in heart failure, but these improvements have not been observed across other conditions, including cancer [8]. Emerging evidence is mixed, with a recent review that focused on all cancer stages demonstrating clinical equipoise, with no discernible difference between telehealth and usual care in improving QOL [15]. However, a recent systematic review focusing specifically on patients with advanced cancer and diverse web and technological interventions (largely providing psychosocial, self-management, and expert-guided support) found that most approaches suggested some degree of efficacy relating to QOL and psychosocial well-being [16]. However, we do not know how well people with advanced cancer engage with these interventions.

With emerging clinical validation demonstrating the potential of digital technology approaches to improve care and outcomes of patients with advanced cancer, usability must also be considered [17]. Subjective aspects of usability require a better understanding, specifically regarding user satisfaction and engagement [17]. Patient engagement can be an important factor in the success of health interventions, leading to better intended health outcomes for the patient and lower health care costs [18]. As such, the effectiveness of telehealth interventions in improving health outcomes is heavily dependent on patient engagement. However, patient engagement is a broad term that can cover multiple levels of how a patient interacts with an intervention. For the purposes of this review, with a focus on technology-based interventions, engagement will be used to refer to the specific quantitative measures of behavior of engagement as defined by Perski et al [19] (ie, comprising the frequency, amount, duration, depth of use, and other measures of use and interaction with a digital health intervention). A previous systematic review found that information technology platforms (eg, mobile phone devices, internet-based interventions, social media, and other web-based communication tools) can help engage patients in health care processes and motivate health behavior change [20]. However, interventions with the intention to help support patients in managing chronic conditions can be complex. There is a need to understand whether different aspects of telehealth interventions uniquely influence patient engagement, especially for patients with advanced cancer who often experience a high symptom burden and functional impairment [21]. Understanding patients’ engagement with telehealth interventions is necessary to further evaluate and refine the implementation of these emerging and promising approaches for patients with advanced cancer. Therefore, there is a need to understand how patients with advanced cancer engage with telehealth interventions and which aspects of these interventions may influence engagement.

Objectives

Past systematic reviews have sought to synthesize the evidence of telehealth interventions among patients with cancer and survivors but have not explored interventions solely intended for and tested on patients with advanced, incurable cancer [15,16]. Understanding patient engagement can help us evaluate and refine further design, development, and evaluation of telehealth approaches for people with advanced cancer. A companion review [22] explored the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the interventions on health and health system outcomes, whereas this review synthesizes the data on patient engagement with the interventions. The aims of this review are as follows: (1) to characterize the extent of behavioral engagement of people with advanced, incurable cancer with telehealth interventions and (2) to explore factors that influence engagement with telehealth interventions.

Methods

Information Sources

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; CRD42018117232). A systematic review of the literature was conducted in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Sociological Abstracts, with studies included from the inception of each electronic database up until December 31, 2020. No lower cutoff date was chosen as there has not been a previous review looking into engagement with telehealth interventions in this population. An example search strategy used for MEDLINE can be found in Multimedia Appendix 1 and includes keywords and medical subject headings. The development of the search strategy was supported by information specialists at the University of Leeds. This search was supplemented by forward and backward citation searching of key papers. This review was reported in line with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 guidelines. The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines directed our process for conducting this systematic review and the decisions made [23].

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if the following applied:

They involved a telehealth intervention, which is defined as “any intervention in which clinical information is transferred remotely between patient and health care provider, regardless of the technology used to record or transmit the information” [8]. This could include symptom measuring or monitoring (eg, Patient-Reported Outcome Measures); education, information giving, and support, including decision aids and advanced care planning; psychological interventions; or medical consultation (telemedicine or teleconsultation). Participants could be located anywhere as long as the intervention that was carried out conformed to the telehealth definition.

They included participants of any age who were living with cancer of any type that could not be cured (advanced, metastatic, or terminal). This included people who had been treated with curative intent but whose cancer had recurred or progressed, those not being treated with curative intent, and those at or near end of life.

They included a measure of engagement as an outcome or reported as part of the study findings. In this review, we used the measures conceptualized as behavior that were identified by Perski et al [19]: frequency, amount, duration, and depth of use.

The studies were carried out in any country at any time.

Risk of bias was not used as a selection criterion for inclusion in the review.

Studies were excluded when the following applied:

The participants included patients with cancer currently being treated with curative intent, and the studies had mixed populations (ie, not 100% of the sample were people with cancer that could not be cured), unless findings pertaining to our population of interest were presented separately in the results section.

The studies did not report primary data (eg, systematic reviews, study protocols, conference abstracts, editorials, and commentaries).

The studies were not in the English language.

Study Selection and Data Collection Process

In total, 2 authors (WG and MA) reviewed titles, abstracts, and full-text papers, assessing them for eligibility independently. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data from the included studies were extracted into a predesigned form by WG and verified by MA to capture study characteristics (design, sample size, cancer type, gender, age, and outcomes). Data were also extracted based upon the items included in the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist (why, what, who provided, how, where, when and how much, tailoring, modifications, and how well) [24].

Quality Assessment

The included studies were assessed for methodological quality and risk of bias independently by 2 authors (WG and MA), with any disagreements resolved through discussion. The risk of bias for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool [25].

Data Synthesis

A narrative synthesis [26] was conducted to outline the design, population, and context (mode of delivery, health care provider, and intervention intensity) of the individual studies. Studies were categorized by their approach to examining intervention effect, differentiating between those exploring pure intervention effect (eg, using blinded RCT designs) and those exploring effect in the context of routine health care [27]. For the primary outcome of engagement, a deductive and inductive approach was taken using the definitions of engagement behavior outlined by Perski et al [19] while also ensuring that other engagement-related data were captured. Engagement data were identified and split into categories based upon the type of engagement the studies measured: frequency (how often contact was made with the intervention over a specified period), the amount or breadth (the total length of each intervention contact), duration (the period over which participants were exposed to an intervention), and depth (variety of content used) [19]. Across these 4 measures, studies were grouped together based upon how they measured the outcome, which was then summarized.

Data from the included studies relating to frequency of use by patients, where reported, were transformed to a percentage of actual patient engagement compared with intended engagement with the intervention to provide a standardized statistical comparison. When overall engagement percentages were calculated, these were weighted by sample size.

To draw associations between the calculated percentage of actual patient engagement, the intensity of the intervention (for the patient and health professional), and mode of delivery, we had to simplify these characteristics. The intensity of the interventions for both the patient and the health professional was coded by a member of the research team (WG). WG reviewed the intervention description in each included study to determine the expected engagement with the intervention for patients and health professionals. This referred to any interaction (both scheduled and unscheduled) that was anticipated or planned with the intervention (eg, a patient having a telephone consultation with a health professional or submitting data via a web-based system). For articles where a second opinion was requested by WG, a second reviewer (MA) discussed the study with WG until a consensus was achieved on the expected engagement reported. The expected engagement was simplified into categories of high, medium, and low expected engagement to make comparisons across studies. For patients, low expected engagement referred to only having ≤3 contacts with the intervention, a medium level of engagement was 4 to 7 expected contacts, and a high level of engagement was ≥8 expected contacts or more than daily reporting of symptoms. A previous study of engagement with a web-based mindfulness intervention identified similar levels of high and low participant engagement (low: 0-4 and high: 5-7); however, a third category was added for this review to account for the studies with >7 contacts [28]. For health professionals, the categories mirrored those for patients if the health professional was required to make contact with the patient (eg, low was ≤3 contacts, medium was 4 to 7 contacts, and high was ≥8 contacts). If the health professional was required to only make contact with the patient when prompted to do so by a patient’s entry on a system or survey, it was coded as low contact on the part of the health professional. For each intervention, we also coded the mode of delivery (eg, telephone, smartphone, or web-based), including interventions where multiple modes were used. We were then able to look at associations between the mode of delivery, expected level of engagement (high, medium, or low for the patient and health professional), and the percentage of actual patient engagement with the intervention.

Results

Search Results

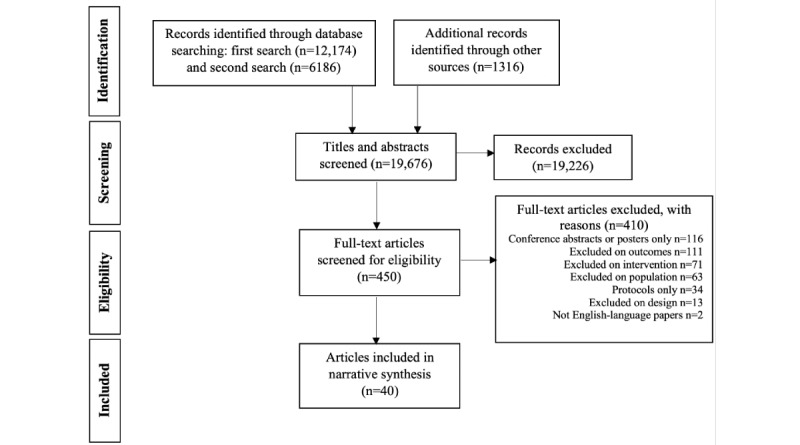

Of the 19,676 papers that were identified in the database search, 0.2% (40/19,676) of papers covering 39 different studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review [29-68]. Figure 1 outlines the PRISMA flow diagram for the included studies and the reasons for exclusion of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 includes a summary of the characteristics of the included studies. Table 2 outlines the characteristics of the included interventions and the engagement outcomes. The included studies had a sample size ranging from 6 [61] to 766 [31] and included multiple RCTs (16/39, 41%) [30,31,33-35,37-39,43-45,48,50,57,63,67,68], with most studies being conducted in the United States (22/39, 56%) [29-31,33,34,37-41,43,45,46,48,50,54,57,59,60,66-68]. Of the 39 studies included in the review, 13 (33%) explored intervention effects in the context of routine care implementation [29,32,36,41,42,49,51,52,58,60-62,64], with the remainder exploring intervention effects often using a blinded controlled trial design.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (N=39).

| Study | Country | Study design | Sample size | Type of cancer | Age (years) | Female participants, n (%) |

| Alter et al [29] | United States | Pilot | 8 | Colorectal | Range 59-79 | 5 (63) |

| Badr et al [30] | United States | RCTa | 39 | Lung | Mean 68 (SD 10) | 29 (74) |

| Basch et al [31] | United States | RCT | IGb: 441; CGc: 325 | Breast, genitourinary, gynecologic, or lung | IG: median 61; CG: median 62 | IG: 257 (58); CG: 187 (58) |

| Bensink et al [32] | Australia | Feasibility | 11 | Advanced cancer, type NRd | Range 3-18 | NR |

| Bouchard et al [33] | United States | RCT | 192 | Prostate | Mean 69 (SD 9) | 0 (0) |

| Bruera et al [34] | United States | RCT | 190 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Median 58 (range 25-84) | 128 (67) |

| Chambers et al [35] | Australia | RCT | 189 | Prostate | Mean 70 (SD 9) | 0 (0) |

| Chavarri-Guerra et al [36] | Mexico | Observational study | 45 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Median 68 (range 33-90) | 26 (58) |

| Cheung et al [37] | United States | RCT | 39 | Breast | NR | 39 (100) |

| Cheville et al [38,39] | United States | RCT | 516 | Multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome, or lymphoma | Mean 66 (SD 11) | 257 (50) |

| Chow et al [40] | United States | Feasibility | 190 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Median 68 (range 39-89) | 94 (49) |

| Cluver et al [41] | United States | Feasibility | 10 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Mean 50 (range 26-61) | 7 (70) |

| Dixon et al [42] | Canada | Feasibility | 69 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Mean 69 | 19 (28) |

| Donovan et al [43] | United States | RCT | 65 | Ovarian | Mean 57 (SD 9) | 65 (100) |

| Eldeib et al [44] | Egypt | RCT | IG: 44; CG: 38 | Colorectal or gastric adenocarcinoma | IG: mean 50 (SD 11); CG: mean 45 (SD 13) | IG: 28 (64); CG: 24 (63) |

| Flannery et al [45] | United States | RCT | IG: 30; CG: 15 | Lung | IG: mean 66 (SD 8); CG: mean 61 (SD 9) | IG: 7 (41); CG: 5 (45) |

| Fleisher et al [46] | United States | Feasibility | 22 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Range 37-77 | 11 (50) |

| Fox et al [48] | United States | RCT | 192 | Prostate | IG: mean 71 (SD 8); CG: mean 71 (SD 9) | 0 (0) |

| Fox et al [47] | Australia | Feasibility | 15 | Melanoma | 26-49 years: n=4 (27%), 50-64 years: n=6 (40%), ≥65 years: n=5 (33%) | 7 (47) |

| Friis et al [49] | Denmark | Feasibility | 20 | Lung | Median 70.5 (range 54-86) | 7 (35) |

| Gustafson et al [50] | United States | RCT | IG: 144; CG: 141 | Lung | IG: mean 62 (SD 11); CG: mean 61 (SD 10) | IG: 62 (50); CG: 59 (48) |

| Haddad et al [51] | Canada | Feasibility | IG: 102; CG: 118 | Lung and others | IG: mean 62 (range 35-83); CG: mean 60 (range 31-87) | IG: 28 (50); CG: 25 (45) |

| Hennemann-Krauss et al [52] | Brazil | Observational study | 12 | Advanced cancer, type NR | Mean 68 (SD 9) | 5 (42) |

| Keikes et al [53] | Netherlands | Feasibility | 155 | Colorectal | NR | NR |

| Liu et al [54] | United States | Pilot | 16 | Ovarian | Median 58 (range 36-80) | NR |

| Nemecek et al [55] | Austria | Feasibility | 15 | Non–small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and pancreatic | Mean 50 | NR |

| Rasschaert [56] | Belgium | Feasibility | 11 | Colorectal, gastric or esophageal, pancreatic, and cholangiocarcinoma | Median 57 (range 44-74) | 6 (55) |

| Rose et al [57] | United States | RCT | 210 | Advanced cancer, type NR | 40-60 (n=109); 61-80 (n=101) | 69 (33) |

| Sardell et al [58] | United Kingdom | Feasibility | 45 | Glioma | Median 50 (range 23-69) | 15 (33) |

| Schmitz et al [59] | United States | Pilot | 7 | Breast | Mean 61 | 7 (100) |

| Sherry et al [60] | United States | Pilot | 41 | Lung | Mean 66 (SD 10) | 29 (71) |

| Trojan et al [61] | Switzerland | Observational study | 6 | Prostate, lung, and urothelial | NR | 0 (0) |

| Upton [62] | United Kingdom | Pilot | 18 | Melanoma | NR | NR |

| Voruganti et al [63] | Canada | RCT | IG: 24; CG: 24 | Breast, colorectal, lung, prostate, ovarian, head and neck, and leukemia, myeloma, or lymphoma | IG: mean 60 (SD 13); CG: mean 60 (SD 14) | IG: 13 (62); CG: 16 (76) |

| Watanabe et al [64] | Canada | Pilot | 44 | Breast, lung, and leukemia, myeloma, or lymphoma | Median 60 (range 20-88) | 18 (41) |

| Weaver et al [65] | United Kingdom | Pilot | 26 | Breast, colorectal | Mean 57 | 12 (46) |

| Wright et al [66] | United States | Pilot | 10 | Gynecologic | Mean 60 (SD 11) | 10 (100) |

| Yanez et al [67] | United States | RCT | 74 | Prostate | Mean 69 (SD 9) | 0 (0) |

| Yount et al [68] | United States | RCT | IG: 123; CG: 130 | Lung | IG: mean 61 (SD 10); CG: mean 60 (SD 10) | IG: 66 (54); CG: 62 (48) |

aRCT: randomized controlled trial.

bIG: intervention group.

cCG: control group.

dNR: not reported.

Table 2.

Intervention details and engagement outcomes (N=39).

| Study | Intervention intensity (duration of the intervention) | Intervention description (content, mode of delivery, health care provider) | Engagement outcomes (frequency, amount, duration, depth, and actual patient engagement) |

| Alter et al [29] |

|

|

|

| Badr et al [30] |

|

|

|

| Basch et al [31] |

|

|

|

| Bensink et al [32] |

|

|

|

| Bouchard et al [33] |

|

|

|

| Bruera et al [34] |

|

|

|

| Chambers et al [35] |

|

|

|

| Chavarri-Guerra et al [36] |

|

|

|

| Cheung et al [37] |

|

|

|

| Cheville et al [38,39] |

|

|

|

| Chow et al [40] |

|

|

|

| Cluver et al [41] |

|

|

|

| Dixon et al [42] |

|

|

|

| Donovan et al [43] |

|

|

|

| Eldeib et al [44] |

|

|

|

| Flannery et al [45] |

|

|

|

| Fleisher et al [46] |

|

|

|

| Fox et al [48] |

|

|

|

| Fox [47] |

|

|

|

| Friis et al [49] |

|

|

|

| Gustafson et al [50] |

|

|

|

| Haddad et al [51] |

|

|

|

| Hennemann-Krause et al [52] |

|

|

|

| Keikes et al [53] |

|

|

|

| Liu et al [54] |

|

|

|

| Nemecek et al [55] |

|

|

|

| Rasschaert [56] |

|

|

|

| Rose et al [57] |

|

|

|

| Sardell et al [58] |

|

|

|

| Schmitz et al [59] |

|

|

|

| Sherry et al [60] |

|

|

|

| Trojan et al [61] |

|

|

|

| Upton [62] |

|

|

|

| Voruganti et al [63] |

|

|

|

| Watanabe et al [64] |

|

|

|

| Weaver et al [65] |

|

|

|

| Wright et al [66] |

|

|

|

| Yanez et al [67] |

|

|

|

| Yount et al [68] |

|

|

|

aPT: physical therapist.

bREST: Rapid Easy Strength Training.

cFSP: First Step Program.

dIG: intervention group.

eIVR: interactive voice response.

fCG: control group.

gWRITE: Written Representational Intervention To Ease Symptoms.

hCHESS: Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System.

iHCP: health care professional.

jeCO: eCediranib/Olaparib.

kGP: general practitioner.

lMDT: multidisciplinary team.

mHP: health promotion.

nCBSM: cognitive behavioral stress management.

Engagement

The engagement outcomes for all studies are outlined in Table 2.

Frequency

Across most studies (36/39, 92%), the frequency of times contact was made with the intervention was reported [29-43,45-47,49-58,60-68]. There was substantial heterogeneity in the measurement of frequency across studies. Of the 39 studies, 13 (33%) reported the percentage of contacts either with the whole intervention or with each individual intended session [30,31,35,40,48-50,54,56,63,65,66,68]. The number of contacts with the intervention overall or each individual session was reported by 69% (27/39) of the studies [29,33,34,36-39,41-43,45,46,49,51-55,57,58,60-67].

Across 44% (17/39) of studies, it was possible to create a standardized percentage of actual patient engagement compared with intended engagement [29,30,32,33,38-40,42,45,46, 51,53,54,56,63,66-68]. This ranged from 51% [53] to 100% [29,30,64], with an average across all 17 studies of 75.4% (SD 15.8%). In the remaining 49% (19/39) of studies, it was not possible to create this standardized statistic because of a lack of reported data, and the design of the intervention meant there was no intended engagement and it was instead tailored to the patients’ needs.

Amount

A total of 31% (12/39) of studies measured the amount of contact with each intervention or with the intervention overall [32,35,36,38,39,43,44,46,47,50,53,57,58]. Of the 39 studies, 3 (8%) measured the average amount of time of each intervention contact (10.5 to 85 minutes) [35,47,57], 2 (5%) reported the average amount of time across all intervention contacts (16 to 65 minutes) [38,39,46] and 1 (3%) reported the total amount of call durations, which could be averaged across all intervention participants to 35.3 minutes [44]. In total, 5% (2/39) of studies reported the median amount of time for each intervention contact (10 to 20 minutes) [32,58], and 5% (2/39) of studies reported the median amount of time across the whole intervention (38 to 146 minutes) [50,53]. A total of 3% (1/39) of studies reported the number of intervention contacts that fell into a range of minutes (eg, 16-30 minutes: 58 contacts) [36]. A total of 3% (1/39) of studies did not report time but, as it was a web-based intervention with communication with the health professional through posts on a message board, instead reported the average length of each post at 260.5 words [43].

Duration

A total of 15% (6/39) of studies that had open-ended interventions reported the length of time that each participant was exposed to the intervention [43,52,56-59]. A total of 10% (4/39) of studies reported the average time of exposure to the intervention, ranging from 62 to 195 days [43,52,57,59]. A total of 3% (1/39) of studies reported a median amount of exposure to the intervention of 6 months [58], and the final study (1/39, 3%) reported the number of participants exposed for >4 weeks (n=5) and >12 weeks (n=1) [56].

Depth

A total of 10% (4/39) of studies reported on the variety of components of the intervention that the participants accessed [36,43,50,64]. Each study measured depth in different ways. A total of 3% (1/39) of studies reported the percentage of time that each health professional was on the teleconference calls [64], and another study (1/39, 3%) simply reported that 75% of patients had completed all elements [43]. The number of different interventions that all participants received was reported by 3% (1/39) of studies [36], and the final study (1/39, 3%) reported that patients had viewed a median of 243 webpages [50].

Association With Intervention Level of Intensity

Expected levels of engagement for both patients and health professionals were reported across low (≤3 contacts), medium (4-7 contacts), and high (≥8 contacts) categories. A total of 13% (5/39) of studies could not be categorized as there was no expected engagement with the intervention, and the extent of engagement was determined at the patient’s discretion [32,36,43,55,63]. Table 3 shows the number of studies with the expected interaction of both the patient and health professional with the intervention. Most studies expected a similar level of interaction from both the patient and health professional in an intervention, but no studies expected more interaction from the health professional than from the patient.

Table 3.

Number of studies with the expected engagement of the patient and health professional (n=34).

| Expected patient interaction with the intervention | Expected health professional interaction with the intervention | ||

|

|

Low, n (%) | Medium, n (%) | High, n (%) |

| Low | 10 (26) | —a | — |

| Medium | 2 (5) | 8 (21) | — |

| High | 7 (18) | — | 7 (18) |

aNo data available for category.

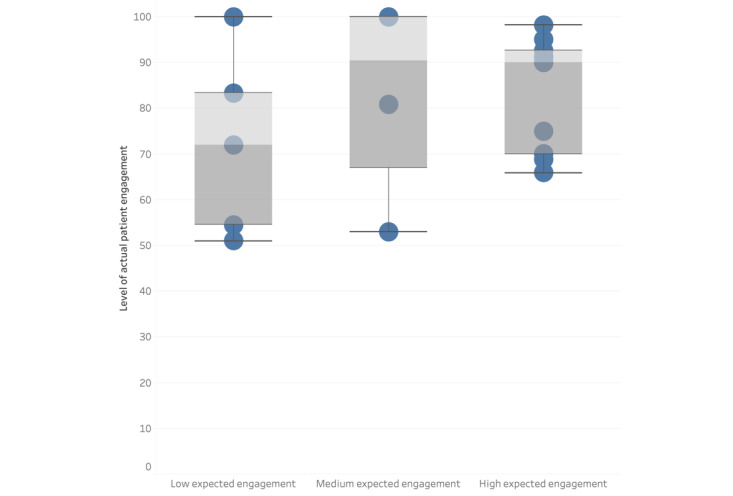

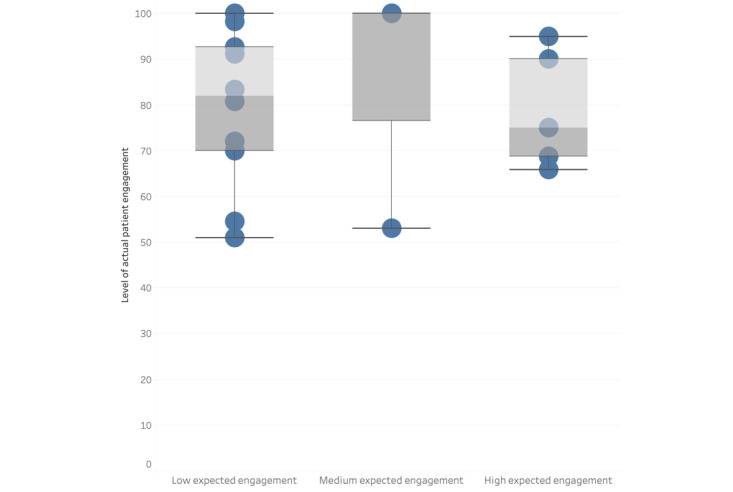

Figures 2 and 3 are graphical representations of the association between expected levels of engagement for the patient (Figure 2) and the health professional (Figure 3) and the percentage of actual engagement with the intervention by the patient. Figure 2 shows that the studies that had low expected engagement for the patients had a combined actual patient engagement of 64% (SD 14.8%); for medium expected engagement, this was 66.9% (SD 16.4%); and, for high expected engagement, this was 87% (SD 8.2%). Figure 3 shows that the category with the highest level of combined actual patient engagement was the studies that expected the health professionals to have a high level of engagement with the intervention (86.6%, SD 8.3%). The studies in the categories of low and medium expected engagement from health professionals had lower levels of combined actual patient engagement (71%, SD 15.2% and 62.3%, SD 15%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Box plot to present the association between expected levels of engagement by the patient and the percentage of actual engagement by the patient.

Figure 3.

Box plot to present the association between expected levels of engagement by the health professional and the percentage of actual engagement by the patient.

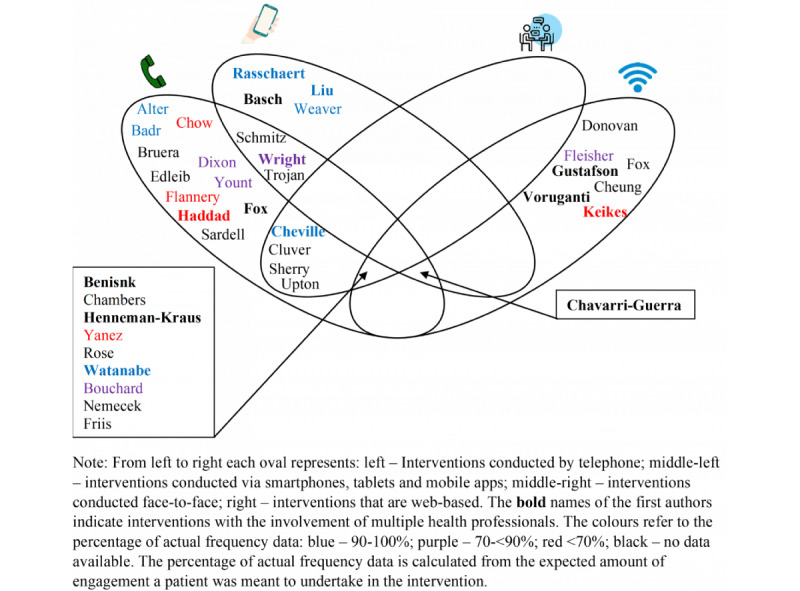

Association With Intervention Mode of Delivery and Health Care Providers

Figure 4 [29-68] shows the modes of delivery of each intervention and where interventions use multiple modes, with the names in bold involving multiple health professionals. The figure also shows, where available, the percentage of actual patient engagement by way of color, with blue showing 90% to 100%, purple showing 70% to 89%, and red showing <70%. Of the 39 studies, 17 (44%) used multiple modes of delivery, whereas the remaining 22 (56%) used 1 mode. The telephone was the most popular mode of delivery (28/39, 72%) followed by web-based delivery of the intervention (17/39, 44%). The use of only a tablet or smartphone app for the intervention appeared to be associated with the most actual patient engagement with an intervention, with 8% (3/39) of studies showing between 90% and 100% engagement [54,56,65]. The use of a telephone was more mixed, with actual patient engagement ranging from 54.5% [51] to 100% [29,30]. Figure 4 also shows broadly how many health care providers were involved in delivering the interventions, with those involving multiple health care providers shown in bold. Those interventions that involved multiple health care providers reported higher patient engagement than those with only 1 health care provider (79.3%, SD 18.5% vs 70.5%, SD 11.5%).

Figure 4.

Modes of delivery of each intervention and, where reported, the percentage of actual frequency of engagement [29-68].

Study Quality

The included studies could be grouped into two broad categories to be assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool: quantitative RCTs and quantitative nonrandomized trials. The RCTs were of a broadly high quality; however, a number of studies did not provide enough information to assess whether the randomization procedure was conducted adequately or whether the groups at baseline were comparable. There were also 15% (6/39) of studies that did not have complete outcome data at follow-up. Among the nonrandomized trials, study quality was again high, apart from the included studies that did not control for confounders in their analysis. This is likely because most of these studies were feasibility or pilot studies and were not powered to detect significance, which would have been inappropriate. A breakdown of how each study was rated can be found in Multimedia Appendix 2 [29-68].

Discussion

Principal Findings

This systematic review is the first to synthesize engagement data from telehealth interventions for people with advanced cancer. This review found that people with advanced cancer were able to successfully engage in telehealth interventions with variable types of telehealth modalities, including telephone, mobile phone–based apps, and web-based interventions, albeit largely in the context of research studies. This review found that the frequency of engagement with the intervention was the most commonly reported measure of engagement, although there was heterogeneity in the method of reporting across the studies. Where standardized comparison was possible across the studies, actual engagement as a proportion of intended engagement was at an average of 75.4% (SD 15.8%). The level of engagement was found to vary based on the expected interaction of both the patient and health care professional and the mode of delivery. Actual patient engagement was higher in studies that expected higher levels of engagement from both the patient and health care professional but was noticeably lower in studies that expected only a low or medium level of engagement. Furthermore, the use of only a tablet or smartphone app for an intervention appeared to be associated with the highest levels of actual patient engagement with an intervention. This could in part be explained by the immediacy of access and reduced steps for accessing an intervention through a mobile phone app when compared with an intervention hosted on a website.

This review is in line with previous reviews that looked at engagement with interventions involving digital technology among people with chronic diseases, which found broadly that there are high levels of engagement with interventions [20]. However, this review provides an overview and critique of existing reporting of engagement for telehealth interventions in patients with advanced cancer and found wide disparities in metrics for engagement used and reported across the included studies. The frequency of interaction with an intervention was reported widely, but other measures of engagement, such as the amount of time spent engaging with the intervention, were not reported as well. Furthermore, the duration and depth of engagement with the intervention were reported by only one-quarter of all included studies (9/39, 23%). This may be due to the design of interventions with a set duration or only 1 component that patients could engage with, but this was not clear across studies. In addition, few studies reported the expected levels of engagement for an intervention, limiting the interpretability of any subsequent reporting of actual patient engagement. Refining and using measures to better understand factors driving digital engagement, including for telehealth, could inform the development of approaches from design through monitoring as part of routine care. For example, the application of engagement measures could serve as a progression criterion in feasibility studies of emerging telehealth approaches. Future research may need to define and develop meaningful and context- and condition-appropriate measures of digital engagement for palliative care to facilitate measurement of digital engagement. Although this review focused on the quantitative measures of behavioral engagement, the future development of a measure should attempt to incorporate components that provide a broader understanding of subjective experiences and aspects of engagement, potentially through qualitative approaches. There is also scope to develop and refine the dimensions comprising the digital engagement framework used to guide the synthesis of data in this study. For example, there is scope to incorporate a temporal element to consider the intensity of the intervention (eg, whether the intervention is spread over a week or months) alongside refining the underpinning definitions of terminology used for each dimension as the framework continues to evolve.

Through this review, we can conclude that there is no standardized method to report engagement in telehealth interventions for people with advanced cancer. The frequency of interactions with the intervention was presented most commonly, although the way in which this was done varied greatly across the studies, and there is a limited ability to understand what this means in the context of the intervention and the proposed and expected engagement needed for clinical utility. For example, people with advanced cancer have fluctuating needs, and a higher level of engagement with an intervention may not relate to the success of the intervention itself but be reflective of worsening outcomes for the patient [69]. In addition, patients may have their symptom management needs met early on in the intervention and may not need further follow-up, which may not be indicative of poor engagement with the intervention per se. With regard to mobile health interventions, the Mobile Health Evaluation, Reporting and Assessment checklist has been developed to help standardize the methodology for reporting the content and context of an intervention to support reproducibility and comparison of interventions [70]. Future iterations of the tool could include, for example, reporting of the expected and actual patient engagement levels of intended users of telehealth interventions alongside frequency of use—the most widely reported measure in this review. These data could complement and contribute to emerging evidence regarding the feasibility and acceptability of telehealth approaches as part of care for people with advanced cancer.

Recent evidence suggests that digital health interventions could provide a degree of efficacy related to QOL and psychosocial well-being [16]. For this review, most included interventions focused on symptom management, with high levels of engagement that suggest potential for its use to support remote monitoring. This approach could facilitate reductions in the required number of in-person visits while enabling continued access to data to inform patient care. However, in order to ensure such an approach is sustainable, there is a need to consider the burden of data entry on patients and the need for review—and potentially response—by health professionals. For patients, emerging approaches provide options for enhancing the richness of data received through remote monitoring without increasing the data burden for patients. For example, wearable technologies can passively collect sensor data on heart rate and activity to inform automatic monitoring and feedback processes [71], augmenting existing approaches without increasing the need for manual data entry. For health professionals, this review found that studies with high levels of intended engagement for both the patient and health care professional were associated with higher levels of actual engagement on the part of the patient. High intended engagement from health care professionals may not be a sustainable approach for digital technology, particularly when considered alongside the additional invisible work that such digital health can create for health professionals (eg, data must be interpreted, made sense of, located within existing knowledge and data sets, and negotiated) [72]. This is important to consider in light of projections of an increasing burden of serious health-related suffering and subsequent demands on palliative care services across geographical regions where demand is increasingly outstripping supply [73,74]. Therefore, for telehealth approaches to be sustainable as part of care for people with advanced cancer, they should seek to balance demands on both the patient and the care team, seeking to achieve maximal information with minimal data burden.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations associated with this review. First, the focus of engagement in this review was on the behavioral aspects that were outlined by Perski et al [19] but not on the subjective measures of engagement, such as interest, attention, and enjoyment. Integrating these subjective measures into a future mixed methods review could allow us to evaluate the experience of interventions. In addition, because of the heterogeneity of the studies and reported approaches to measuring engagement, such as frequency, it is difficult to determine exactly which components of interventions contribute to higher engagement levels. We were only able to draw associations, and future research is needed to better explore causal factors. Furthermore, although this review looked at the extent of engagement, how it was measured across studies, and the association with the study characteristics, we did not assess whether engagement led to an improvement in patient-reported outcomes or experience. A future review should consider how engagement interacts with patient-reported outcomes. In addition, when determining the categories for low, medium, and high expected engagement, we did not take into account the time frame of the intervention; therefore, 2 studies could be grouped together with different levels of intervention intensity. Furthermore, most of the studies included in this review explored the intervention effect through mostly controlled studies, which could bias the recruitment toward those individuals who were motivated and more likely to be technologically literate. The levels of engagement identified in this review may not then translate into routine clinical care if these studies and their intervention effect have to date been confined to exploration in the context of RCTs and similar study approaches. This review also limited the included studies to those written in English; therefore, this review may not contain the entirety of related studies.

Conclusions

This review identified that, where reported, there is a high level of engagement with telehealth interventions among people with advanced cancer. We identified that actual patient engagement is associated with both the expected level of engagement of the patient and the health professional as well as the mode of delivery of the intervention. We highlighted the heterogeneity in the reporting of engagement results across the research and the need to improve such reporting guidelines. As treatment delivery becomes increasingly more dependent on remote or telehealth modalities, the inclusion of a measure of engagement in future telehealth evaluations is essential to enable the comparisons of interaction and use across intervention approaches and to provide further granularity in factors that determine optimal implementation of telehealth approaches. There is a need for consistent measurement and reporting of domains relating to digital engagement (eg, breadth, duration, and frequency) with the scope to amend or develop measures. This will increase the ease of reporting of engagement in future studies, inform which telehealth intervention components are linked to variations in engagement, facilitate evidence syntheses, and support the development of condition-specific benchmarks of digital engagement for people with advanced cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by Yorkshire Cancer Research (award reference EN/LR1/007) and Macmillan Cancer Research (award reference 6488078).

Abbreviations

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- QOL

quality of life

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE.

Quality appraisal tables of quantitative randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized trials.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021 Aug 15;127(16):3029–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33587. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waller A, Girgis A, Johnson C, Lecathelinais C, Sibbritt D, Forstner D, Liauw W, Currow DC. Improving outcomes for people with progressive cancer: interrupted time series trial of a needs assessment intervention. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012 Mar;43(3):569–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.020. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885-3924(11)00451-9 .S0885-3924(11)00451-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016 Jun;51(6):1070–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885-3924(16)30048-3 .S0885-3924(16)30048-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henson LA, Maddocks M, Evans C, Davidson M, Hicks S, Higginson IJ. Palliative care and the management of common distressing symptoms in advanced cancer: pain, breathlessness, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Mar 20;38(9):905–14. doi: 10.1200/jco.19.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kühnbach R, Haberland B, Higginson IJ. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010 Sep;13(9):1109–18. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang S, Liu L, Lin KC, Chung JH, Hsieh CH, Chou WC, Su PJ. Trajectories of the multidimensional dying experience for terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014 Nov;48(5):863–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.011. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885-3924(14)00184-5 .S0885-3924(14)00184-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel MI, Periyakoil VS, Blayney DW, Moore D, Nevedal A, Asch S, Milstein A, Coker TR. Redesigning cancer care delivery: views from patients and caregivers. J Oncol Pract. 2017 Apr;13(4):291–302. doi: 10.1200/jop.2016.017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanlon P, Daines L, Campbell C, McKinstry B, Weller D, Pinnock H. Telehealth interventions to support self-management of long-term conditions: a systematic metareview of diabetes, heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017 May 17;19(5):e172. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6688. http://www.jmir.org/2017/5/e172/ v19i5e172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aapro M, Bossi P, Dasari A, Fallowfield L, Gascón P, Geller M, Jordan K, Kim J, Martin K, Porzig S. Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2020 Oct;28(10):4589–612. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05539-1. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32533435 .10.1007/s00520-020-05539-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burbury K, Wong Z, Yip D, Thomas H, Brooks P, Gilham L, Piper A, Solo I, Underhill C. Telehealth in cancer care: during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Intern Med J. 2021 Jan;51(1):125–33. doi: 10.1111/imj.15039. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33572014 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charalambous A. Utilizing the advances in digital health solutions to manage care in cancer patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(3):234–7. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_72_18. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2347-5625(21)00258-4 .S2347-5625(21)00258-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warrington L, Absolom K, Conner M, Kellar I, Clayton B, Ayres M, Velikova G. Electronic systems for patients to report and manage side effects of cancer treatment: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Jan 24;21(1):e10875. doi: 10.2196/10875. https://www.jmir.org/2019/1/e10875/ v21i1e10875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockie SJ, Bottorff JL, Robinson CA, Pesut B. Experiences of rural family caregivers who assist with commuting for palliative care. Can J Nurs Res. 2010 Mar;42(1):74–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pesut B, Robinson CA, Bottorff JL, Fyles G, Broughton S. On the road again: patient perspectives on commuting for palliative care. Pall Supp Care. 2010 Mar 23;8(2):187–95. doi: 10.1017/s1478951509990940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2018 Jun;24(6):397–405. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kane K, Kennedy F, Absolom KL, Harley C, Velikova G. Quality of life support in advanced cancer-web and technological interventions: systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021 Apr 26; doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002820.bmjspcare-2020-002820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews SC, McShea MJ, Hanley CL, Ravitz A, Labrique AB, Cohen AB. Digital health: a path to validation. NPJ Digit Med. 2019 Oct 17;2(1):38. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0111-3. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0111-3.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dentzer S. Rx for the 'blockbuster drug' of patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Feb;32(2):202. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0037. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0037.32/2/202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perski O, Blandford A, West R, Michie S. Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Transl Behav Med. 2017 Jun;7(2):254–67. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27966189 .10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawesi S, Rashrash M, Phalakornkule K, Carpenter JS, Jones JF. The impact of information technology on patient engagement and health behavior change: a systematic review of the literature. JMIR Med Inform. 2016 Jan 21;4(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/medinform.4514. http://medinform.jmir.org/2016/1/e1/ v4i1e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lage D, El-Jawahri A, Fuh C, Newcomb R, Jackson V, Ryan D, Greer JA, Temel JS, Nipp RD. Functional impairment, symptom burden, and clinical outcomes among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020 Jun;18(6):747–54. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7385.jnccn19249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagnall AM, Ashley L, Hulme C, Jones R, Freeman C, Rithalia A, Yaziji N, King N. Systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telehealth interventions for people with cancer that cannot be cured. PROSPERO. 2018. [2022-01-28]. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018117232 .

- 23.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. York: CRD, University of York; 2009. Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan A, Michie S. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br Med J. 2014 Mar 07;348(mar07 3):g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong Q, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau M, Vedel I, Pluye P. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Edu Inform. 2018 Dec 18;34(4):285–91. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Methods Programme. 2006. [2022-01-28]. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf .

- 27.Malmivaara A. Pure intervention effect or effect in routine health care - blinded or non-blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018 Aug 31;18(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0549-z. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-018-0549-z .10.1186/s12874-018-0549-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr DC, Ornelas IJ, Lilly MM, Calhoun R, Meischke H. Participant engagement in and perspectives on a web-based mindfulness intervention for 9-1-1 telecommunicators: multimethod study. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Jun 19;21(6):e13449. doi: 10.2196/13449. https://www.jmir.org/2019/6/e13449/ v21i6e13449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alter CL, Fleishman SB, Kornblith AB, Holland JC, Biano D, Levenson R, Vinciguerra V, Rai KR. Supportive telephone intervention for patients receiving chemotherapy: a pilot study. Psychosomatics. 1996 Sep;37(5):425–31. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(96)71529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badr H, Smith CB, Goldstein NE, Gomez JE, Redd WH. Dyadic psychosocial intervention for advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers: results of a randomized pilot trial. Cancer. 2015 Jan 01;121(1):150–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29009. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, Rogak L, Bennett AV, Dueck AC, Atkinson TM, Chou JF, Dulko D, Sit L, Barz A, Novotny P, Fruscione M, Sloan JA, Schrag D. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Feb 20;34(6):557–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830.JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bensink M, Armfield N, Pinkerton R, Irving H, Hallahan A, Theodoros D, Russell T, Barnett A, Scuffham P, Wootton R. Using videotelephony to support paediatric oncology-related palliative care in the home: from abandoned RCT to acceptability study. Palliat Med. 2009 Apr 27;23(3):228–37. doi: 10.1177/0269216308100251.0269216308100251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouchard L, Yanez B, Dahn J, Flury S, Perry K, Mohr D, Penedo FJ. Brief report of a tablet-delivered psychosocial intervention for men with advanced prostate cancer: acceptability and efficacy by race. Transl Behav Med. 2019 Jul 16;9(4):629–37. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby089. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30285186 .5114618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruera E, Yennurajalingam S, Palmer JL, Perez-Cruz PE, Frisbee-Hume S, Allo JA, Williams JL, Cohen MZ. Methylphenidate and/or a nursing telephone intervention for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jul 01;31(19):2421–7. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.45.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chambers SK, Occhipinti S, Foley E, Clutton S, Legg M, Berry M, Stockler MR, Frydenberg M, Gardiner RA, Lepore SJ, Davis ID, Smith DP. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in advanced prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan 20;35(3):291–7. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.68.8788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chávarri-Guerra Y, Ramos-López WA, Covarrubias-Gómez A, Sánchez-Román S, Quiroz-Friedman P, Alcocer-Castillejos N, Milke-García MD, Carrillo-Soto M, Morales-Alfaro A, Medina-Palma M, Aguilar-Velazco JC, Morales-Barba K, Razcon-Echegaray A, Maldonado J, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E. Providing supportive and palliative care using telemedicine for patients with advanced cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Oncologist. 2021 Mar;26(3):512–5. doi: 10.1002/onco.13568. https://academic.oup.com/oncolo/article-lookup/doi/10.1002/onco.13568 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung EO, Cohn MA, Dunn LB, Melisko ME, Morgan S, Penedo FJ, Salsman JM, Shumay DM, Moskowitz JT. A randomized pilot trial of a positive affect skill intervention (lessons in linking affect and coping) for women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2017 Dec 27;26(12):2101–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.4312. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27862646 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheville AL, Moynihan T, Basford JR, Nyman JA, Tuma ML, Macken DA, Therneau T, Satelel D, Kroenke K. The rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of collaborative telecare in preserving function among patients with late stage cancer and hematologic conditions. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018 Jan;64:254–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.08.021. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28887068 .S1551-7144(17)30157-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheville AL, Moynihan T, Herrin J, Loprinzi C, Kroenke K. Effect of collaborative telerehabilitation on functional impairment and pain among patients with advanced-stage cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019 May 01;5(5):644–52. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0011. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30946436 .2729683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow E, Wong R, Connolly R, Hruby G, Franzcr. Franssen E, Fung KW, Vachon M, Andersson L, Pope J, Holden L, Szumacher E, Schueller T, Stefaniuk K, Finkelstein J, Hayter C, Danjoux C. Prospective assessment of symptom palliation for patients attending a rapid response radiotherapy program. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001 Aug;22(2):649–56. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cluver JS, Schuyler D, Frueh BC, Brescia F, Arana GW. Remote psychotherapy for terminally ill cancer patients. J Telemed Telecare. 2005 Jun 23;11(3):157–9. doi: 10.1258/1357633053688741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon W, Pituskin E, Fairchild A, Ghosh S, Danielson B. The feasibility of telephone follow-up led by a radiation therapist: experience in a multidisciplinary bone metastases clinic. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2010 Dec;41(4):175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2010.10.003. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2010.10.003.S1939-8654(10)00077-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donovan HS, Ward SE, Sereika SM, Knapp JE, Sherwood PR, Bender CM, Edwards RP, Fields M, Ingel R. Web-based symptom management for women with recurrent ovarian cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial of the WRITE Symptoms intervention. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014 Feb;47(2):218–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.04.005. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885-3924(13)00318-7 .S0885-3924(13)00318-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eldeib HK, Abbassi MM, Hussein MM, Salem SE, Sabry NA. The effect of telephone-based follow-up on adherence, efficacy, and toxicity of oral capecitabine-based chemotherapy. Telemed J E Health. 2019 Jun;25(6):462–70. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flannery M, Stein K, Dougherty D, Mohile S, Guido J, Wells N. Nurse-delivered symptom assessment for individuals with advanced lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018 Sep 1;45(5):619–30. doi: 10.1188/18.onf.619-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleisher L, Buzaglo J, Collins M, Millard J, Miller SM, Egleston BL, Solarino N, Trinastic J, Cegala DJ, Benson AB, Schulman KA, Weinfurt KP, Sulmasy D, Diefenbach MA, Meropol NJ. Using health communication best practices to develop a web-based provider-patient communication aid: the CONNECT study. Patient Educ Couns. 2008 Jun;71(3):378–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.017. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18417312 .S0738-3991(08)00127-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox J, Janda M, Bennett F, Langbecker D. An outreach telephone program for advanced melanoma supportive care: acceptability and feasibility. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019 Oct;42:110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.08.010.S1462-3889(19)30119-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox RS, Moreno PI, Yanez B, Estabrook R, Thomas J, Bouchard LC, McGinty HL, Mohr DC, Begale MJ, Flury SC, Perry KT, Kundu SD, Penedo FJ. Integrating PROMIS® computerized adaptive tests into a web-based intervention for prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2019 May;38(5):403–9. doi: 10.1037/hea0000672. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31045423 .2019-23038-009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friis RB, Hjollund NH, Mejdahl CT, Pappot H, Skuladottir H. Electronic symptom monitoring in patients with metastatic lung cancer: a feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2020 Jun 17;10(6):e035673. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035673. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32554725 .bmjopen-2019-035673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gustafson DH, DuBenske LL, Namkoong K, Hawkins R, Chih M, Atwood AK, Johnson R, Bhattacharya A, Carmack CL, Traynor AM, Campbell TC, Buss MK, Govindan R, Schiller JH, Cleary JF. An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Cancer. 2013 May 1;119(9):1744–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haddad P, Wilson P, Wong R, Williams D, Sharma N, Soban F, McLean M, Levin W, Bezjak A. The success of data collection in the palliative setting--telephone or clinic follow-up? Support Care Cancer. 2003 Sep;11(9):555–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hennemann-Krause L, Lopes AJ, Araújo JA, Petersen EM, Nunes RA. The assessment of telemedicine to support outpatient palliative care in advanced cancer. Pall Supp Care. 2014 Aug 27;13(4):1025–30. doi: 10.1017/s147895151400100x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keikes L, de Vos-Geelen J, de Groot JW, Punt CJ, Simkens LH, Trajkovic-Vidakovic M, Portielje JE, Vos AH, Beerepoot LV, Hunting CB, Koopman M, van Oijen MG. Implementation, participation and satisfaction rates of a web-based decision support tool for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019 Jul;102(7):1331–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.020.S0738-3991(18)30861-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu JF, Lee J, Strock E, Phillips R, Mari K, Killiam B, Bonam M, Milenkova T, Kohn EC, Ivy SP. Technology applications: use of digital health technology to enable drug development. JCO Clin Cancer Informat. 2018 Dec;(2):1–12. doi: 10.1200/cci.17.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nemecek R, Huber P, Schur S, Masel EK, Baumann L, Hoeller C, Watzke H, Binder M. Telemedically augmented palliative care : empowerment for patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019 Dec 30;131(23-24):620–6. doi: 10.1007/s00508-019-01562-3.10.1007/s00508-019-01562-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasschaert M, Helsen S, Rolfo C, Van Brussel I, Ravelingien J, Peeters M. Feasibility of an interactive electronic self-report tool for oral cancer therapy in an outpatient setting. Support Care Cancer. 2016 Aug 30;24(8):3567–71. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3186-2.10.1007/s00520-016-3186-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rose J, Bowman K, Radziewicz R, Lewis S, O'Toole E. Predictors of engagement in a coping and communication support intervention for older patients with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Nov;57 Suppl 2:296–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02517.x.JGS2517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sardell S, Sharpe G, Ashley S, Guerrero D, Brada M. Evaluation of a nurse-led telephone clinic in the follow-up of patients with malignant glioma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2000 Feb;12(1):36–41. doi: 10.1053/clon.2000.9108.S0936-6555(00)99108-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmitz KH, Zhang X, Winkels R, Schleicher E, Mathis K, Doerksen S, Cream L, Rosenberg J, Kass R, Farnan M, Halpin-Murphy P, Suess R, Zucker D, Hayes M. Developing "Nurse AMIE": a tablet-based supportive care intervention for women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2020 Jan 06;29(1):232–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sherry V, Guerra C, Ranganathan A, Schneider S. Metastatic lung cancer and distress: use of the distress thermometer for patient assessment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017 Jun 1;21(3):379–83. doi: 10.1188/17.cjon.379-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trojan A, Huber U, Brauchbar M, Petrausch U. Consilium smartphone app for real-world electronically captured patient-reported outcome monitoring in cancer patients undergoing anti-PD-L1-directed treatment. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13(2):491–6. doi: 10.1159/000507345. https://www.karger.com?DOI=10.1159/000507345 .cro-0013-0491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Upton J. Nurse-led telephone assessments for patients receiving ipilimumab. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2016 Mar 10;15(2):30–5. doi: 10.7748/cnp.15.2.30.s21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, Kurahashi AM, Lokuge B, Krzyzanowska MK, Mamdani M, Moineddin R, Husain A. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Jul 18;19(7):e219. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7421. https://www.jmir.org/2017/7/e219/ v19i7e219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watanabe SM, Fairchild A, Pituskin E, Borgersen P, Hanson J, Fassbender K. Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: report of a pilot project. Support Care Cancer. 2013 Apr;21(4):1201–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1649-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weaver A, Love SB, Larsen M, Shanyinde M, Waters R, Grainger L, Shearwood V, Brooks C, Gibson O, Young AM, Tarassenko L. A pilot study: dose adaptation of capecitabine using mobile phone toxicity monitoring - supporting patients in their homes. Support Care Cancer. 2014 Oct;22(10):2677–85. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wright AA, Raman N, Staples P, Schonholz S, Cronin A, Carlson K, Keating NL, Onnela J. The hope pilot study: harnessing patient-reported outcomes and biometric data to enhance cancer care. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018 Dec;2:1–12. doi: 10.1200/CCI.17.00149. http://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/CCI.17.00149?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yanez B, McGinty HL, Mohr DC, Begale MJ, Dahn JR, Flury SC, Perry KT, Penedo FJ. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a technology-assisted psychosocial intervention for racially diverse men with advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. 2015 Dec 15;121(24):4407–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29658. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yount SE, Rothrock N, Bass M, Beaumont JL, Pach D, Lad T, Patel J, Corona M, Weiland R, Del CK, Cella D. A randomized trial of weekly symptom telemonitoring in advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014 Jun;47(6):973–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.07.013. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24210705 .S0885-3924(13)00481-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Brien H, Morton E, Kampen A, Barnes S, Michalak E. Beyond clicks and downloads: a call for a more comprehensive approach to measuring mobile-health app engagement. BJPsych Open. 2020 Aug 11;6(5):e86. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.72. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2056472420000721/type/journal_article .S2056472420000721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agarwal S, LeFevre AE, Lee J, L'Engle K, Mehl G, Sinha C, Labrique A, WHO mHealth Technical Evidence Review Group Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. Br Med J. 2016 Mar 17;352:i1174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nwosu AC, Quinn C, Samuels J, Mason S, Payne TR. Wearable smartwatch technology to monitor symptoms in advanced illness. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018 Jun 03;8(2):237. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001445. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29101119 .bmjspcare-2017-001445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lupton D. The digitally engaged patient: self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Soc Theory Health. 2013 Jun 19;11(3):256–70. doi: 10.1057/sth.2013.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, Salsberg ES. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018 Apr;55(4):1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.011. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885-3924(18)30031-9 .S0885-3924(18)30031-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, Higginson IJ, Gomes B, Harding R. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Global Health. 2019 Jul;7(7):883–92. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30172-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE.

Quality appraisal tables of quantitative randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized trials.