Key Points

Question

Do racial and ethnic minority individuals with glaucoma have different rates of cost-related barriers to medication adherence compared with non-Hispanic White individuals?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 3826 patients with glaucoma, significantly higher odds of self-reported difficulty affording medication were observed among non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic individuals compared with non-Hispanic White individuals.

Meaning

This study suggests that racial and ethnic minority individuals with glaucoma have greater cost-related barriers to obtaining medication, even after controlling for individualized socioeconomic factors.

This cross-sectional study evaluates cost-related barriers to medication adherence by race and ethnicity in a nationwide cohort of patients with glaucoma.

Abstract

Importance

Ability to afford medication is a major determinate of medication adherence among patients.

Objective

To determine cost-related barriers to medication adherence by race and ethnicity in a nationwide cohort of patients with glaucoma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study included patients with glaucoma enrolled in the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program, a nationwide longitudinal cohort of US adults, with more than 300 000 currently enrolled. Individuals with a diagnosis of glaucoma based on electronic health record diagnosis codes who participated in the Health Care Access and Utilization survey and had complete data on all covariates were studied. Data were collected from June 2016 to March 2021, and data were analyzed from August to November 2021.

Exposures

Race and ethnicity defined as non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between reported cost-related barriers to medication adherence (could not afford prescription medication, skipped medication doses to save money, took less medication to save money, delayed filling a prescription to save money, asked for lower-cost medication to save money, bought prescriptions from another country to save money, and used alternative therapies to save money) and race and ethnicity, adjusting multivariable models by age, gender, health insurance status, education, and income. Odds ratios of these barriers were obtained by race and ethnicity, with non-Hispanic White race as the reference group.

Results

Of 3826 included patients with glaucoma, 481 (12.6%) were African American, 119 (3.1%) were non-Hispanic Asian, 351 (9.2%) were Hispanic, and 2875 (75.1%) were non-Hispanic White. The median (IQR) age was 69 (60-75) years, and 2307 (60.3%) were female. After adjusting for confounders, non-Hispanic African American individuals (odds ratio, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.34-2.44) and Hispanic individuals (odds ratio, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.25-2.49) were more likely than non-Hispanic White individuals to report not being able to afford medications. Further, despite having the lowest rate of endorsing difficulty affording medications, non-Hispanic White individuals were equally likely to ask for lower-cost medication from their clinicians as individuals of racial and ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, there was significantly higher odds of self-reported difficulty affording medications among non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic individuals compared with non-Hispanic White individuals. Clinicians should be proactive and initiate discussions about costs in an effort to promote medication adherence and health equity among patients.

Introduction

Glaucoma is the most common cause of irreversible blindness in the world, and it is projected to affect more than 110 million individuals by 2040.1 In the US, the prevalence of open-angle glaucoma is projected to nearly double to 7.32 million by 2050.2 African American and Hispanic individuals have a much higher prevalence of open-angle glaucoma (5.6% and 4.7%, respectively) than their non-Hispanic White counterparts (1.7%).2 Combined with shifting demographic characteristics, this suggests that Hispanic individuals in the US will experience the greatest total glaucoma burden by 2035.2 Racial and ethnic minority individuals in the US with glaucoma face several challenges, including disparities in diagnostic testing,3 delayed detection of glaucoma progression,4,5 poor enrollment in clinical trials,6 and having higher rates of medication nonadherence,7,8,9 which can hasten progression to blindness.10

In the US, it is estimated that 30% to 50% of medications are not taken as prescribed, accounting for approximately 10% of hospitalizations, $100 billion in health care expenditures, and 125 000 preventable deaths annually.11 Medication adherence is a challenge common to multiple chronic diseases and is related to a variety of factors. Patients may have difficulty obtaining, administering, or dosing their medications. Moreover, they may be unconvinced that their medication is effective, a common sentiment for patients with largely asymptomatic diseases, such as glaucoma.12 These challenges are especially difficult to overcome in the context of cost-related barriers. A recent study by Gupta et al13 found that patients with glaucoma were significantly more likely to report cost-related nonadherence to medications compared with participants without glaucoma. However, how these measures of cost-related barriers differ by race and ethnicity among patients with glaucoma is less clear.

Being a chronic disease that frequently requires access to health care, close follow-up, and sometimes complicated and expensive medical and surgical regimens, glaucoma outcomes are often tied to socioeconomic factors, which are invariably linked with race and ethnicity in the US.14 In this study, we evaluated rates of self-reported cost-related barriers to medication adherence by race and ethnicity in a nationwide cohort of patients with glaucoma.

Methods

Study Population

We obtained data from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) All of Us Research Program, a nationwide database with an emphasis on diversity aiming to enroll at least 1 million people.15 At the time of our analysis, 331 380 participants were contained in the version 5 data set. Institutional review board (IRB)/ethics committee approval was obtained. Participants provided written informed consent at enrollment in the study, which was approved by the NIH All of Us IRB. The All of Us program collects a wide range of data from participants, including physical measurements, electronic health record (EHR) data, survey data, wearable data, and biospecimen collection.15 Participants are given a one-time compensation of $25 in the form of cash, gift card, or electronic voucher if asked to give physical measurements or specimens. All of Us data undergo deidentification processes prior to becoming available to researchers.15 Secondary analyses of deidentified data, such as evaluated for our study, are considered non–human subjects research, which was verified by the University of California, San Diego IRB. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. We used Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for observational studies.16

The racial categories provided by the NIH All of Us Research Program include African American, Asian, White, multiple, and other. These racial categories were self-identified by participants. Other racial categories, such as American Indian and Alaskan Native and Pacific Islanders, were not available on the NIH All of Us program owing to insufficient enrollment and risk of identification. In our analysis, we excluded participants who did not report race and ethnicity information as well as those who reported other or multiple races owing to insufficient enrollment to provide statistical power. This effectively restricted our study population to non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White individuals.

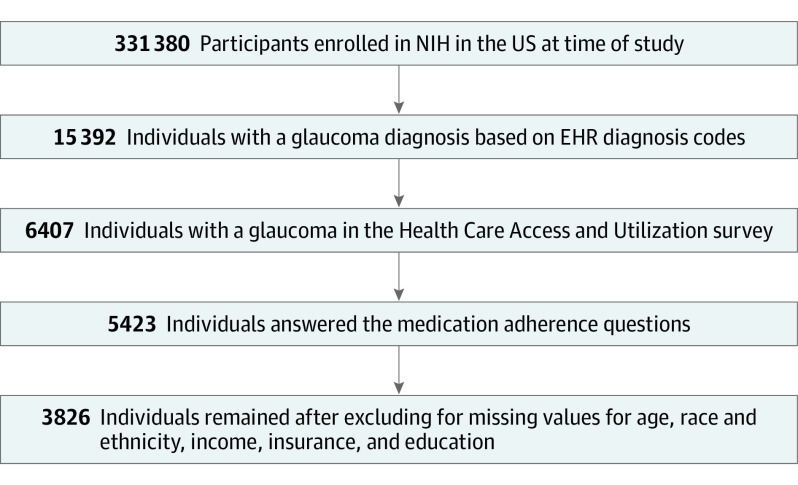

A total of 15 392 individuals were identified in the All of Us database with a diagnosis of glaucoma based on electronic health record diagnosis codes, of which 6407 individuals (41.6%) answered at least 1 question in the Health Care Access and Utilization survey, which includes questions relating to cost and medication adherence. These were validated survey questions derived from the National Health Interview Survey.17 From these, 5423 (84.6%) answered the medication adherence questions examined in this study. Further, we dropped observations with missing values for select covariates used in our analysis (age, race and ethnicity, income, insurance status, and education), yielding 3826 individuals (70.6%) in our final data set (Figure).

Figure. Flowchart of Exclusion Criteria Leading to a Final Study Population of 3826 Patients With Glaucoma.

EHR indicates electronic health record; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Variables

We studied 7 dichotomous (yes/no) questions in the All of Us Health Care Access & Utilization survey as follows: during the past 12 months, was there any time where you could not afford prescription medication; skipped medication doses to save money; took less medicine to save money; delayed filling a prescription to save money; asked your physician for a lower-cost medication to save money; bought prescription drugs from another country to save money; or used alternative therapies to save money.18 Information regarding additional covariates were extracted from participants’ survey responses in the All of Us Basics survey.18 Age in years was categorized as less than 40 years, 40 to 64 years, 65 to 74 years, 75 to 84 years, and 85 years or older. Annual income in dollars was categorized as less than $25 000, $25 000 to $50 000, $50 000 to $100 000, $100 000 to $200 000, and more than $200 000. Insurance status was categorized as Medicaid, other insured (employer provided, privately purchased, Medicare, military provided, Veterans Administration provided, or other), and no insurance—prioritized in that order if participants had multiple types of insurance. Education was categorized as no high school diploma, high school diploma/GED, some college, and college and greater.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between various patient characteristics and survey responses were analyzed by race and ethnicity using Pearson χ2 tests to generate unadjusted P values, using the Holm-Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. We used logistic regression to generate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs to characterize responses regarding cost-related barriers to medication adherence (ie, the proportion responding yes to each survey question) between different races and ethnicities, with non-Hispanic White individuals as the reference group. We calculated univariable and multivariable models adjusting for age, gender, insurance status, education, and income. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and P values were considered statistically significant at the α = .05 level. Analyses were conducted on the NIH All of Us Researcher Workbench using R software version 4.1.0 (The R Foundation) and are available in the referenced notebook.19

Results

Of the 3826 individuals with glaucoma in our study population, 481 (12.6%) were African American, 119 (3.1%) were non-Hispanic Asian, 351 (9.2%) were Hispanic, and 2875 (75.1%) were non-Hispanic White. The median (IQR) age was 69 (60-75) years, and 2307 (60.3%) were female. Non-Hispanic White individuals had the highest median (IQR) age (70 [64-76] years) compared with non-Hispanic African American individuals (63 [56-70] years), non-Hispanic Asian individuals (59 [45-71.5] years), and Hispanic individuals (60 [50.5-69] years). Uninsured participants represented only 0.1% of the study population, while 396 (10.4%) had Medicaid insurance and 3426 (89.5%) had other insurance. Overall, 359 respondents (9.4%) reported that they could not afford medication, 503 (5.3%) skipped medications, 227 (5.9%) took less medication, 317 (8.3%) delayed filling medication, 730 (19.1%) asked for lower-cost medication, 140 (3.7%) bought medication from another country, and 198 (5.2%) used alternative therapies to save money in the past 12 months—which all significantly varied by race and ethnicity in Pearson χ2 tests (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of Selected Characteristics for Patients With Glaucoma by Race and Ethnicity.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | P valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic African American | Non-Hispanic Asian | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | Total | ||

| Total | 481 (12.6) | 119 (3.1) | 351 (9.2) | 2875 (75.1) | 3826 (100) | NA |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63 (56-70) | 59 (45-71.5) | 60 (50.5-69) | 70 (64-76) | 69 (60-75) | NA |

| Age category, y | ||||||

| <40 | <20 | 21 (17.6) | 41 (11.7) | 86 (3.0) | 164 (4.3) | <.001 |

| 40-64 | 245 (50.9) | 51 (42.9) | 175 (49.9) | 699 (24.3) | 1170 (30.6) | |

| 65-74 | 165 (34.3) | 27 (22.7) | 102 (29.1) | 1128 (39.2) | 1422 (37.2) | |

| 75-84 | 48 (10.0) | <20 | 29 (8.3) | 864 (30.1) | 960 (25.1) | |

| ≥85 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 98 (3.4) | 110 (2.9) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 343 (71.3) | 73 (61.3) | 221 (63.0) | 1670 (58.1) | 2307 (60.3) | <.001 |

| Male | 136 (28.3) | 45 (37.8) | 126 (35.9) | 1169 (40.7) | 1476 (38.6) | |

| Other/skipped | <20 | <20 | <20 | 36 (1.3) | 43 (1.1) | |

| Income, $ | ||||||

| <25 000 | 199 (41.4) | <20 | 135 (38.5) | 312 (10.9) | 657 (17.2) | <.001 |

| 25 000-50 000 | 92 (19.1) | <20 | 60 (17.1) | 482 (16.8) | 645 (16.9) | |

| 50 000-100 000 | 123 (25.6) | 31 (26.1) | 85 (24.2) | 931 (32.4) | 1170 (30.6) | |

| 100 000-200 000 | 51 (10.6) | 48 (40.3) | 52 (14.8) | 800 (27.8) | 951 (24.9) | |

| >200 000 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 350 (12.2) | 403 (10.5) | |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Medicaid | 131 (27.2) | <20 | 99 (28.2) | 158 (5.5) | 396 (10.4) | <.001 |

| Other insured | 349 (72.6) | 111 (93.3) | 252 (71.8) | 2714 (94.4) | 3426 (89.5) | |

| None | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | |

| Education | ||||||

| No high school diploma | 33 (6.9) | <20 | 43 (12.3) | <20 | 95 (2.5) | <.001 |

| High school diploma/GED | 83 (17.3) | <20 | 51 (14.5) | 228 (7.9) | 366 (9.6) | |

| Some college | 158 (32.8) | <20 | 105 (29.9) | 707 (24.6) | 976 (25.5) | |

| College and above | 207 (4.0) | 109 (91.6) | 152 (43.3) | 1921 (66.8) | 2389 (62.4) | |

| Could not afford medication | ||||||

| Yes | 91 (18.9) | <20 | 60 (17.1) | 195 (6.8) | 359 (9.4) | <.001 |

| No | 390 (81.1) | 106 (89.1) | 291 (82.9) | 2680 (93.2) | 3467 (90.6) | |

| Skipped medication to save money | ||||||

| Yes | 50 (10.4) | <20 | 22 (6.3) | 125 (4.3) | 203 (5.3) | <.001 |

| No | 431 (89.6) | 113 (95.0) | 329 (93.7) | 2750 (95.7) | 3623 (94.7) | |

| Took less medication to save money | ||||||

| Yes | 49 (10.2) | <20 | 23 (6.6) | 147 (5.1) | 227 (5.9) | <.001 |

| No | 432 (89.8) | 111 (93.3) | 328 (93.4) | 2728 (94.9) | 3599 (94.1) | |

| Delayed filling medication | ||||||

| Yes | 63 (13.1) | <20 | 37 (10.5) | 204 (7.1) | 317 (8.3) | <.001 |

| No | 418 (86.9) | 106 (89.1) | 314 (89.5) | 2671 (92.9) | 3509 (91.7) | |

| Asked for lower cost medication | ||||||

| Yes | 79 (16.4) | 21 (17.6) | 74 (21.1) | 556 (19.3) | 730 (19.1) | <.001 |

| No | 402 (83.6) | 98 (82.4) | 277 (78.9) | 2319 (80.7) | 3096 (80.9) | |

| Bought medication from another country | ||||||

| Yes | <20 | <20 | <20 | 113 (3.9) | 140 (3.7) | <.001 |

| No | 479 (99.6) | 110 (92.4) | 335 (95.4) | 2762 (96.1) | 3686 (96.3) | |

| Used alternative therapies to save money | ||||||

| Yes | 34 (7.1) | <20 | 27 (7.7) | 131 (4.6) | 198 (5.2) | .02 |

| No | 447 (92.9) | 113 (95.0) | 324 (92.3) | 2744 (95.4) | 3628 (94.8) | |

Abbreviations: GED, general educational development; NA, not applicable.

Per the All of Us Research Program data sharing policies, cells with less than 20 respondents are suppressed.

P values were generated from Pearson χ2 tests using the Holm-Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

By race and ethnicity, 91 non-Hispanic African American individuals (18.9%), 20 non-Hispanic Asian individuals (16.8%), and 60 Hispanic individuals (17.1%) reported not being able to afford medications in the past 12 months. Further, 79 non-Hispanic African American individuals (16.4%), 21 non-Hispanic Asian individuals (17.6%), 74 Hispanic individuals (21.1%), and 556 non-Hispanic White individuals (19.3%) reported asking for lower-cost medications in the past 12 months. Overall, 152 non-Hispanic African American individuals (31.6%), 37 non-Hispanic Asian individuals (31.0%), 113 Hispanic individuals (32.2%), and 777 non-Hispanic White individuals (27.0%) answered yes to at least 1 cost-related medication adherence survey question. Overall, 152 non-Hispanic African American individuals (31.6%), 37 non-Hispanic Asian individuals (31.0%), 113 Hispanic individuals (32.2%), and 777 non-Hispanic White individuals (27.0%) answered yes to at least 1 cost-related medication adherence survey question.

In unadjusted univariable logistic regression models, non-Hispanic African American individuals (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 2.44-4.19) and Hispanic individuals (OR, 2.83; 95% CI, 2.06-3.86) were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic White individuals to report not being able to afford medication. Non-Hispanic African American individuals were more likely to report skipping medication and taking less medication and less likely to report buying medication from another country to save than non-Hispanic White individuals. Further, both non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic individuals were more likely to report delaying filling medication and using alternative therapies to save than non-Hispanic White individuals (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression for the Association Between Cost-Related Barriers to Medication Adherence by Race and Ethnicity.

| Variable | Non-Hispanic White (n = 2875) | Non-Hispanic African American (n = 481) | Non-Hispanic Asian (n = 119) | Hispanic (n = 351) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P valuea | OR (95% CI) | P valuea | OR (95% CI) | P valuea | ||

| Univariable logistic regression | |||||||

| Could not afford medication | 1 [Reference] | 3.21 (2.44-4.19) | <.001 | 1.69 (0.89-2.94) | .09 | 2.83 (2.06-3.86) | <.001 |

| Skipped medication to save money | 1 [Reference] | 2.55 (1.80-3.58) | <.001 | 1.17 (0.45-2.49) | .72 | 1.47 (0.90-2.30) | .14 |

| Took less medication to save money | 1 [Reference] | 2.10 (1.49-2.93) | <.001 | 1.34 (0.59-2.63) | .44 | 1.30 (0.81-2.01) | .34 |

| Delayed filling medication | 1 [Reference] | 1.97 (1.45-2.65) | <.001 | 1.61 (0.85-2.80) | .12 | 1.54 (1.05-2.21) | .03 |

| Asked for lower-cost medication | 1 [Reference] | 0.82 (0.63-1.06) | .26 | 0.89 (0.54-1.42) | .65 | 1.11 (0.84-1.46) | .58 |

| Bought medications from another country | 1 [Reference] | 0.10 (0.02-0.32) | .002 | 2.00 (0.92-3.84) | .07 | 1.17 (0.66-1.94) | .57 |

| Used alternative medication to save money | 1 [Reference] | 1.59 (1.06-2.33) | .03 | 1.11 (0.43-2.37) | .80 | 1.75 (1.11-2.64) | .02 |

| Multivariable logistic regressionb | |||||||

| Could not afford medication | 1 [Reference] | 1.82 (1.34-2.44) | <.001 | 1.67 (0.85-3.03) | .14 | 1.77 (1.25-2.49) | .002 |

| Skipped medication to save money | 1 [Reference] | 1.27 (0.87-1.85) | .36 | 1.02 (0.38-2.29) | .96 | 0.77 (0.46-1.24) | .47 |

| Took less medication to save money | 1 [Reference] | 1.16 (0.80-1.67) | .62 | 1.21 (0.52-2.49) | .78 | 0.75 (0.45-1.20) | .44 |

| Delayed filling medication | 1 [Reference] | 1.14 (0.82-1.58) | .47 | 1.31 (0.67-2.38) | .47 | 0.91 (0.61-1.35) | .69 |

| Asked for lower-cost medication | 1 [Reference] | 0.78 (0.58-1.02) | .13 | 0.89 (0.53-1.44) | .70 | 1.20 (0.89-1.60) | .33 |

| Bought medications from another country | 1 [Reference] | 0.12 (0.02-0.40) | .04 | 2.27 (1.03-4.45) | .17c | 1.48 (0.80-2.58) | .55 |

| Used alternative medication to save money | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.63-1.46) | .99 | 0.88 (0.33-1.94) | .97 | 1.15 (0.71-1.80) | .82 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

P values were generated using the Holm-Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons, while 95% CIs are unadjusted for Holm-Bonferroni.

Adjusted for age, gender, insurance status, education, and income.

P value without Holm-Bonferroni adjustment = .03.

In multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for age, gender, insurance status, education, and income, non-Hispanic African American individuals (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.34-2.44) and Hispanic individuals (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.25-2.49) were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic White individuals to report not being able to afford medication (Table 2). Further, non-Hispanic African American individuals (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.02-0.40) were less likely than non-Hispanic White individuals to report buying medications from another country to save (Table 2).

Discussion

In this nationwide study of a large cohort of 3826 patients with glaucoma, we found that racial and ethnic minority individuals had differing responses to survey questions regarding cost-related barriers to medication adherence. Further, we found that non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic individuals were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic White individuals to report not being able to afford medication in the previous 12 months. This trend was attenuated but still persisted even after controlling for socioeconomic variables, such as income, insurance status, and education. We also found that non-Hispanic African American individuals were less likely to report buying medications from another country than non-Hispanic White individuals. The latter result must be interpreted with caution due to small numbers.

As a whole, patients with glaucoma are relatively disadvantaged and have higher rates of cost-related barriers to medication adherence compared with patients without a diagnosis of glaucoma.13 Our overall pattern of response rates mirror those reported by Gupta et al13 using the National Health Interview Survey, on which the Health Care Access and Utilization survey in NIH All of Us Research Program was based. Difficulty affording medication imposes yet another barrier that patients with glaucoma must overcome to preserve their vision against this progressive, often asymptomatic chronic disease. Beyond this, the racial and ethnic disparities in the pattern of response rates we observed complicates attempts to promote health equity among patients with glaucoma.

Racial disparities in glaucoma outcomes may be mediated through several different mechanisms, including genetic causes,20 differences in surgical outcomes,21 and adherence to medical regimens.22 It is notable that one study reported that race alone significantly predicted 11% of full treatment adherence to glaucoma medication.7 The persistence of disparities despite controlling for individualized socioeconomic factors suggests that at least some of the disparity may be mitigated at the physician level. Eye care clinicians hoping to promote health equity can take a proactive role in ensuring their patients obtain medications that are not only effective but also affordable. It is well documented that physicians commonly lack accurate knowledge about the cost of medications they prescribe.23 Such costs often are obfuscated by varying medication coverage among different insurance plans.23 Further, prescription of generic drugs is often underutilized, largely owing to unfamiliarity of these options, their price differences, patient preferences, and incorrectly perceived superiority of branded products.24 This has contributed to ophthalmologists prescribing a higher brand-name medication prescription volume than any other prescriber group.25 Offering lower-cost options to all patients is critical because many patients do not discuss cost concerns with their physicians,26 even as national expenditures for ophthalmic medications continue to rise.27

This is evident in our study results; although only 195 non-Hispanic White individuals (6.8%) reported not being able to afford medications, 556 (19.3%) asked for lower-cost medications. In contrast, a much higher percentage of non-Hispanic African American individuals reported not being able to afford medications (91 [18.9%]), and a lower percentage asked for lower cost medications (79 [16.4%]) (Table 1). There is evidence that racial and ethnic minority populations are less likely to advocate for themselves in health care settings.28 Further, White patients have been shown to be more comfortable than African American patients with asking for cheaper medications and are more aware of lower-cost options.29 Although reasons for this hesitancy are multifactorial, clinicians can help circumvent these problems by initiating conversations about cost with their patients.30

Many health care professionals—ophthalmologists included—do not routinely discuss medication costs during patient visits.31 However, there are several tools that can be used by prescribers to help their patients find the lowest-cost medication options. Ideally, integration of medication cost information in electronic health records can provide prescribers with an idea of what their patient will ultimately pay. Such information can facilitate a discussion of the pros and cons of each option during the patient encounter. There is evidence that these features can lead to lower health care expenditures.32,33 If these integrated tools are not available, several free websites and mobile applications exist that show options for low-cost medications and may offer relatively large discounts for ophthalmic patients in particular.34 Besides changes made on the individual level, the practice of ophthalmology as a whole can help promote health equity by creating a more diverse workforce—which has been shown to improve health outcomes for patients35—as well as promoting cost-conscious education among medical students and residents.36

Ensuring patients have access to affordable medication is an essential first step to medication adherence. Other approaches that have shown to be effective can be as simple as face-to-face counseling and monitoring of adherence.37 The criterion standard of directly monitoring adherence is electronic medication monitoring, such as sensors on eyedrop bottles that can convey detailed information about frequency and dosage.38 Early efforts to ensure proper medication adherence is especially important given evidence that adherence patterns to newly prescribed glaucoma medication in the first year mirrors adherence in later years.39 These adherence technologies may become more prevalent in the future with decreasing costs,38 and improved adherence may ultimately lower health care expenditure.40 However, these medication monitoring approaches are ineffectual if patients do not obtain their medications due to cost-related barriers.

Limitations

Our study must be interpreted in the context of a few limitations. First, as with all surveys, responses may have been affected by social desirability and recall bias. However, we would not expect these biases to affect groups differently. Second, information of disease severity was not obtained, which may have influenced how participants answered questions relating to cost barriers for treatment of their disease—ie, those with more severe or symptomatic disease may be less likely to see cost as a barrier to obtaining medications. This may have brought expected results toward the null for racial and ethnic groups that are known to have more advanced disease on average, such as those of African descent.4 However, without disease severity information, we could not explore the relative contributions and potential interactions between these characteristics in greater detail.

Third, 1597 cases were excluded because of missing values for variables used in the regression analysis. It is possible that excluded patients have characteristics that differ from those retained in the analysis, which may affect study results. However, one advantage of the All of Us program was that the size of the database allowed us to retain participants with complete data for the analysis and still be adequately powered to detect differences; no imputation of missing data was required. Fourth, as with all models controlling for socioeconomic variables, some residual confounding may occur. A more comprehensive measure of social deprivation experienced by participants may include zip code–level measures of safety, transportation options, and proximity to health care professionals and pharmacies, which may challenge efforts to be adherent with medication. However, these zip code–level data are not currently available in this database, which provides state-level location information that is not granular enough to estimate social deprivation. Future studies may further elucidate the extent to which cost-related measures of medication adherence is mediated by socioeconomic factors and which factors play the largest roles.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we observed significantly higher odds of self-reported difficulty affording medication among non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic individuals compared with non-Hispanic White individuals. Clinicians should take a proactive role in prescribing medications that are most compatible with their patients’ ability to pay in an effort to promote medication adherence and health equity among patients with glaucoma.

References

- 1.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081-2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vajaranant TS, Wu S, Torres M, Varma R. The changing face of primary open-angle glaucoma in the United States: demographic and geographic changes from 2011 to 2050. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(2):303-314.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein JD, Talwar N, Laverne AM, Nan B, Lichter PR. Racial disparities in the use of ancillary testing to evaluate individuals with open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(12):1579-1588. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gracitelli CPB, Zangwill LM, Diniz-Filho A, et al. Detection of glaucoma progression in individuals of African descent compared with those of European descent. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(4):329-335. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stagg B, Mariottoni EB, Berchuck S, et al. Longitudinal visual field variability and the ability to detect glaucoma progression in Black and White individuals. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;bjophthalmol-2020-318104. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-318104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allison K, Patel DG, Greene L. Racial and ethnic disparities in primary open-angle glaucoma clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e218348. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreer LE, Girkin C, Mansberger SL. Determinants of medication adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(4):234-240. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31821dac86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami Y, Lee BW, Duncan M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in adherence to glaucoma follow-up visits in a county hospital population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(7):872-878. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rees G, Chong XL, Cheung CY, et al. Beliefs and adherence to glaucoma treatment: a comparison of patients from diverse cultures. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(5):293-298. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3182741f1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, et al. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2398-2402. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kini V, Ho PM. Interventions to improve medication adherence: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2461-2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJ, Vervloet M, van Dijk L. Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:675-682. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S29549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta D, Ehrlich JR, Newman-Casey PA, Stagg B. Cost-related medication nonadherence in a nationally representative US population with self-reported glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2021;4(2):126-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, et al. ; All of Us Research Program Investigators . The “All of Us” Research Program. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):668-676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Division of Health Interview Statistics National Center for Health Statistics . 2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release: survey description. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2018/srvydesc.pdf

- 18.National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program Investigators . Survey explorer. Accessed September 5, 2021. https://www.researchallofus.org/data-tools/survey-explorer/

- 19.Disparities in Cost-Related Glaucoma Medication Adherence NIH All of Us Analysis Notebook . Analysis notebook for racial and ethnic disparities in cost-related barriers to medication adherence among glaucoma patients with glaucoma enrolled in the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://workbench.researchallofus.org/workspaces/aou-rw-4d3ba6a6/duplicateofsdhaineyeconditionsv5dataset/notebooks/preview/GlaucomaAccessUtilFinal.ipynb

- 20.Dai Y, Ning X, Han G, Li W. Assessment of the association between isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation and mortality risk of glioblastoma patients. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1501-1508. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9104-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taubenslag KJ, Kammer JA. Outcomes disparities between Black and White populations in the surgical management of glaucoma. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31(4):385-393. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2016.1154163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman DS, Okeke CO, Jampel HD, et al. Risk factors for poor adherence to eyedrops in electronically monitored patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(6):1097-1105. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reichert S, Simon T, Halm EA. Physicians’ attitudes about prescribing and knowledge of the costs of common medications. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2799-2803. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietze J, Priluck A, High R, Havens S. Reasons for the underutilization of generic drugs by US ophthalmologists: a survey. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;9(4):955-970. doi: 10.1007/s40123-020-00292-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman-Casey PA, Woodward MA, Niziol LM, Lee PP, De Lott LB. Brand medications and Medicare Part D: how eye care providers’ prescribing patterns influence costs. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):332-339. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai JC. A comprehensive perspective on patient adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11)(suppl):S30-S36. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen EM, Kombo N, Teng CC, Mruthyunjaya P, Nwanyanwu K, Parikh R. Ophthalmic medication expenditures and out-of-pocket spending: an analysis of United States prescriptions from 2007 through 2016. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(10):1292-1302. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiltshire J, Cronin K, Sarto GE, Brown R. Self-advocacy during the medical encounter: use of health information and racial/ethnic differences. Med Care. 2006;44(2):100-109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196975.52557.b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalawari P, Patel NM, Bzdawka W, Petrone J, Liou V, Armbrecht E. Racial differences in beliefs of physician prescribing practices for low-cost pharmacy options. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):396-403. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beran MS, Laouri M, Suttorp M, Brook R. Medication costs: the role physicians play with their senior patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(1):102-107. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slota C, Davis SA, Blalock SJ, et al. Patient-physician communication on medication cost during glaucoma visits. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(12):1095-1101. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMullin ST, Lonergan TP, Rynearson CS, Doerr TD, Veregge PA, Scanlan ES. Impact of an evidence-based computerized decision support system on primary care prescription costs. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):494-498. doi: 10.1370/afm.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aluga D, Nnyanzi LA, King N, Okolie EA, Raby P. Effect of electronic prescribing compared to paper-based (handwritten) prescribing on primary medication adherence in an outpatient setting: a systematic review. Appl Clin Inform. 2021;12(4):845-855. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1735182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young BK, Kohli AA. Cost analysis of medications in ophthalmology consultations using mobile applications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(8):1809-1810. doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguwa UT, Srikumaran D, Brown N, Woreta F. Improving racial diversity in the ophthalmology workforce: a call to action for leaders in ophthalmology. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;223:306-307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care—what is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1253-1255. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman-Casey PA, Dayno M, Robin AL. Systematic review of educational interventions to improve glaucoma medication adherence: an update in 2015. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2016;11(1):5-20. doi: 10.1586/17469899.2016.1134318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erras A, Shahrvini B, Weinreb RN, Baxter SL. Review of glaucoma medication adherence monitoring in the digital health era. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;bjophthalmol-2020-317918. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman-Casey PA, Blachley T, Lee PP, Heisler M, Farris KB, Stein JD. Patterns of glaucoma medication adherence over four years of follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(10):2010-2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meier-Gibbons F, Töteberg-Harms M. Influence of cost of care and adherence in glaucoma management: an update. J Ophthalmol. 2020;2020:5901537. doi: 10.1155/2020/5901537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]