Key Points

Question

What factors underlie racial disparity in the use of prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) among Black and White patients with prostate cancer?

Findings

This population-based cohort study of 39 534 Medicare beneficiaries found that Black patients with prostate cancer were less likely than White patients to receive a prostate MRI. Mediation analysis revealed that geographic differences, socioeconomic status, and racialized residential segregation were associated with most of the Black vs White racial disparity in prostate MRI use.

Meaning

This study suggests that efforts to address racial disparity in the use of prostate MRI should address upstream factors, including socioeconomic status, geographic variation in practice, and structural racism.

Abstract

Importance

Racial disparity in the use of prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) presents obstacles to closing gaps in prostate cancer diagnosis, treatment, and outcome.

Objective

To identify clinical, sociodemographic, and structural processes underlying racial disparity in the use of prostate MRI among men with a new diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study used mediation analysis to assess claims in the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare database for prostate MRI among 39 534 patients with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2015. Statistical analysis was performed from April 1, 2020, to September 1, 2021.

Exposure

Diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Claims for prostate MRI within 6 months before or after diagnosis of prostate cancer were assessed. Candidate clinical and sociodemographic meditators were identified based on their association with both race and prostate MRI, including the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE), as specified to measure racialized residential segregation. Mediation analysis was performed using nonlinear multiple additive regression trees models to estimate the direct and indirect effects of mediators.

Results

A total of 39 534 eligible male patients (3979 Black patients [10.1%] and 32 585 White patients [82.4%]; mean [SD] age, 72.8 [5.3] years) were identified. Black patients with prostate cancer were less likely than White patients to receive a prostate MRI (6.3% vs 9.9%; unadjusted odds ratio, 0.62, 95% CI, 0.54-0.70). Approximately 24% (95% CI, 14%-32%) of the racial disparity in prostate MRI use between Black and White patients was attributable to geographic differences (SEER registry), 19% (95% CI, 11%-28%) was attributable to neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (residence in a high-poverty area), 19% (95% CI, 10%-29%) was attributable to racialized residential segregation (ICE quintile), and 11% (95% CI, 7%-16%) was attributable to a marker of individual-level socioeconomic status (dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid). Clinical and pathologic factors were not significant mediators. In this model, the identified mediators accounted for 81% (95% CI, 64%-98%) of the observed racial disparity in prostate MRI use between Black and White patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this this population-based cohort study of US adults, mediation analysis revealed that sociodemographic factors and manifestations of structural racism, including poverty and residential segregation, explained most of the racial disparity in the use of prostate MRI among older Black and White men with prostate cancer. These findings can be applied to develop targeted strategies to improve cancer care equity.

This cohort study uses data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database to identify clinical, sociodemographic, and structural processes underlying racial disparity in the use of prostate magnetic resonance imaging among men with a new diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Introduction

There are entrenched racial disparities in the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of men with prostate cancer in the United States.1 Black men are more likely to receive a diagnosis of prostate cancer, are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care, and experience a nearly 2-fold greater risk of cancer-specific mortality compared with White men. Recent analyses suggest that observed racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes are wholly or, at least in part, attributable to factors that are associated with race, but only through generations of the legal, social, and medical (ie, “structural”) disadvantages experienced by Black persons in the US, and are not the result of immutable biological differences.2,3 Race-based differences in prostate cancer care and outcomes also recapitulate other health disparities in the US associated with socioeconomic deprivation, geography, and timeliness and quality of care.4 For example, residential segregation, a form of structural racism resulting from discriminatory practices such as New Deal era “redlining” (intentional discriminatory practices enacted in a geographic area based on race or ethnicity), has been associated with race-based differences in prostate cancer detection and outcomes.5,6,7 Thus, strategies to reduce race-based inequalities begin with broader acknowledgment of their existence and the processes that underlie their perpetuation.8,9

Racial disparity in the use of emerging diagnostic technologies may widen gaps in cancer treatment and outcomes. Advancements in detection and treatment have led to substantial reductions in prostate cancer mortality.10 As a diagnostic tool, prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) improves the identification of prostate cancer and can enhance decision-making.11 However, in many instances, access to emerging medical technologies mirrors treatment disparities across axes of race, geography, and socioeconomic status.12,13,14,15 Early evidence indicates that racial disparities extend to the use of prostate MRI. Lower use of prostate MRI has been reported among non-White patients in a study using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare database.16 Other single-institution studies have also demonstrated racial, insurance, and age disparities in the use of prostate MRI.17,18 However, beyond the description of the existence of these disparities, no information is available to explain their root causes or the extent to which they can be targeted by restorative interventions. In particular, residential and economic racial segregation—manifestations of systemic racism—are associated with cancer disparities but are unexplored as mediators of prostate cancer imaging disparity.5,6,7 A better understanding of the factors that promote racial disparity in prostate MRI is therefore needed to develop strategies to promote equity.

In this study, we aimed to identify the factors that underlie racial disparity in the use of prostate MRI among a population-based cohort of US patients with prostate cancer. Via mediation analysis, we assessed potential mediating roles of clinical, sociodemographic, and structural factors in disparity in the use of prostate MRI. We accounted for established geographic drivers of racial disparity in cancer care, including neighborhood-level poverty and variation across SEER registries, as well as residential segregation. We then decomposed the total effect of a patient’s race on their probability of receiving an MRI into those contributed indirectly by mediating constituents. Through this approach, we aim to inform strategies for interventions that could be leveraged to enhance cancer care equity.19

Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study using data from the SEER-Medicare linked database. In this population-based sample of Medicare beneficiaries, we used a method of multiple mediation analysis to explore the existence of intervening variables (mediators) in the potential causal pathway between race and MRI use.20 These data were available through a collaboration between the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, combining tumor registries across the US with Medicare hospital, physician, and outpatient claims for older patients.21 We included patients aged 66 years or older who received a diagnosis of clinically localized (ie, nonmetastatic and lymph node–negative) prostate cancer between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2015. The Yale Human Investigation Committee determined that this study did not constitute human participants research and did not require institutional review board approval. Reporting of mediation analysis was conducted in adherence to the consensus-based Guideline for Reporting Mediation Analyses (AGReMA) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).22

We excluded patients without evidence of prostate biopsy, unknown month of diagnosis or diagnosis reported on death certificate or autopsy, prior cancer diagnosis, death within 6 months, or subsequent diagnosis of a secondary cancer within 12 months after diagnosis, as well as patients with evidence of prior treatment. To ensure complete reporting of Medicare claims, we required continuous enrollment in fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B beginning 1 year prior through 6 months after diagnosis.

Study Variables

The primary study outcome was receipt of prostate MRI in the 13-month period surrounding prostate cancer diagnosis (inclusive of the month of diagnosis and 6 months before and after diagnosis). We defined race as Black, White, or other (American Indian and Alaska Native, as well as Asian and Other Pacific Islander). The primary comparisons were performed between patients whose race was identified as Black or White. Secondary comparisons were conducted between patients whose race was identified as Black or other, based on the sample distribution.

At the patient level, we compiled clinical and pathologic characteristics available in the SEER-Medicare database, including age, medical comorbidity (using a modification of the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index), and disability status.23 To quantify cancer risk status, we aggregated prognostic prostate cancer variables (prostate-specific antigen level, age, Gleason score, and clinical stage) and calculated a modified version of the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score by excluding the number of cores positive for cancer because these data were unavailable.24 Patient-level sociodemographic characteristics included marital status and dual eligibility for Medicaid and Medicare. We assessed whether each patient had 1 month or more of Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, based on demonstration of low household income and resources based on federal guidelines, in the 12 to 6 months before diagnosis (ie, the 6-month period prior to the start of the MRI assessment window).25,26

We examined the proposed effects of small-area socioeconomic and health care measures. Using poverty levels at the patient census tract or zip code level, we specified a binary indicator for whether 20% or more of patients or less than 20% of patients were below the poverty line.27 To account for known regional variation in the intensity of prostate cancer imaging, we constructed a measure to assess the intensity of overall imaging within a patient’s hospital referral region (HRR) using a broader sample of patients who received a diagnosis of prostate cancer from 2008 to 2015.28 Within each HRR, we identified claims for computed tomography and bone scans among patients with prostate cancer in the 1 year before diagnosis through 6 months after diagnosis (eTable 2 in the Supplement). We stratified HRRs by their relative quartile of overall imaging use.

We accounted for measures of residential segregation using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) for race. This measure was used to quantify the extent to which an area’s population is concentrated into extremes of racialized deprivation or privilege.29,30,31 We calculated the ICE for each census tract or zip code (if census tract was unavailable) as the difference in the number of Black and White residents divided by the total population, resulting in values ranging from −1 to 1.32,33 Thus, higher scores reflect greater degrees of racialized residential segregation. We categorized values by quintile, whereby increasing ICE categories reflect higher numbers of persons who are Black vs White.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed from April 1, 2020, to September 1, 2021. We examined the associations among patient’s race, sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and health care–related characteristics, and MRI receipt in the 13-month period surrounding diagnosis. We described patients’ characteristics using frequency tables, mean (SD) values, and χ2 tests as appropriate. We first examined the unadjusted association between race and receipt of prostate MRI among men with prostate cancer. Then, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the association between clinical and sociodemographic factors and prostate MRI use.

Mediation Analysis

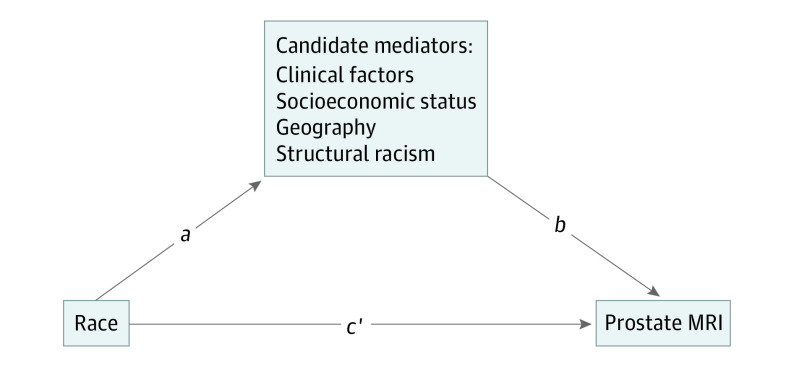

We performed multiple mediation analysis to evaluate the factors underlying observed racial disparity in prostate MRI use (eMethods in the Supplement). We proposed a mediation model to identify the presence and relative contributions of factors that are influenced by the independent variable (race) and that may exert indirect effects on the dependent variable (prostate MRI use). Our conceptual model included candidate mediators across the following 4 domains: (1) clinical and pathologic characteristics of incident prostate cancers, (2) patient-level sociodemographic factors, (3) spatial characteristics measured at the neighborhood level and SEER region level, and (4) structural racism (Figure 1).34 The purpose of this approach is not to exhaustively define all factors that underlie prostate MRI use but rather to explore the existence and feasibility of identifying processes that mediate known racial disparity.

Figure 1. Path Diagram Demonstrating Proposed Total Effect of Race on the Receipt of Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

The proposed total effect of race on receipt of MRI is through mediated indirect effects (the product of a and b) and direct effects of race (c’).

We used a generalized method for mediation analysis with multiple additive regression trees. Compared with linear methods, this nonlinear approach integrates variables across levels of measurement and variable types and also better accounts for potential complex predictor-mediator effects and multicollinearities.35,36,37 We reported the direct and indirect effects of race with MRI receipt through log odds and relative effect sizes (as percentages) using 100 bootstrap iterations to accommodate uncertainty of the estimates. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and mediation analysis was performed using the mma software package in R, version 3.6.3 (R Group for Statistical Computing).

Results

We identified 39 534 eligible patients (3979 Black patients [10.1%], 32 585 White patients [82.4%], and 2970 patients [7.5%] of other races; mean [SD] age, 72.8 [5.3] years) with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer from 2011 to 2015 (Table 1). Prostate MRI use increased during the study period from 5.3% of patients diagnosed in 2011 to 17.5% of those diagnosed in 2015. Black patients were less likely than White patients to receive a prostate MRI (6.3% vs 9.9%; unadjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.62; 95% CI, 0.54-0.70). Disparity in the use of prostate MRI was attenuated after adjustment for available clinical and sociodemographic variables (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.76-1.03). Receipt of prostate MRI was similar between patients whose race was identified as White and patients whose race was identified other (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.79-1.04).

Table 1. Clinical and Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Cohort by MRI Receipt Status.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No MRI | MRI | |

| Overall | 39 534 (100) | 35 783 (90.5) | 3751 (9.5) |

| Age, y | |||

| 66-69 | 12 864 (32.5) | 11 413 (31.9) | 1451 (38.7) |

| 70-74 | 13 964 (35.3) | 12 608 (35.2) | 1356 (36.2) |

| 75-79 | 8075 (20.4) | 7406 (20.7) | 669 (17.8) |

| 80-84 | 3399 (8.6) | 3184 (8.9) | 215 (5.7) |

| ≥85 | 1232 (3.1) | 1172 (3.3) | 60 (1.6) |

| Race | |||

| Black | 3979 (10.1) | 3728 (10.4) | 251 (6.7) |

| White | 32 585 (82.4) | 29 369 (82.1) | 3216 (85.7) |

| Otherb | 2970 (7.5) | 2686 (7.5) | 284 (7.6) |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 118 (0.3) | >107 (>0.3) | <11 (<0.3) |

| Asian and Other Pacific Islander | 1438 (3.6) | 1303 (3.6) | 135 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 1414 (3.6) | <1276 (<3.6) | >138 (>3.6) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Latino | 2340 (5.9) | 2162 (6.0) | 178 (4.8) |

| Non-Latino | 37 194 (94.1) | 33 621 (94.0) | 3573 (95.2) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 25 661 (64.9) | 23 011 (64.3) | 2650 (70.6) |

| Not married | 6999 (17.7) | 6404 (17.9) | 595 (15.9) |

| Unknown | 6874 (17.4) | 6368 (17.8) | 506 (13.5) |

| % of Region with high school degree or less | |||

| <30 | 14 157 (35.8) | 12 186 (34.1) | 1971 (52.5) |

| 30-39 | 7356 (18.6) | 6707 (18.7) | 649 (17.3) |

| 40-49 | 6838 (17.3) | 6345 (17.7) | 493 (13.1) |

| 50-59 | 5481 (13.9) | 5135 (14.4) | 346 (9.2) |

| ≥60 | >5691 (>14.4) | >5399 (<15.1) | >281 (>7.5) |

| Unknown | <11 (<0.03) | <11 (<0.03) | <11 (<0.29) |

| % of Census tract below poverty level | |||

| <5 | 9622 (24.3) | 8350 (23.3) | 1272 (33.9) |

| 5 to <10 | 11 135 (28.2) | 9877 (27.6) | 1258 (33.5) |

| 10 to <20 | 11 166 (28.2) | 10 340 (28.9) | 826 (22.0) |

| 20 to 100 | >7600 (>19.2) | >7205 (>20.1) | >384 (>10.2) |

| Unknown | <11 (<0.03) | <11 (<0.03) | <11 (<0.29) |

| Dual eligibility for Medicaid | |||

| No | 36 331 (91.9) | 32 743 (91.5) | 3588 (95.7) |

| Yes | 3203 (8.1) | 3040 (8.5) | 163 (4.3) |

| Disability status | |||

| Not disabled | 38 873 (98.3) | 35 154 (98.2) | 3719 (99.1) |

| Disabled | 661 (1.7) | 629 (1.8) | 32 (0.9) |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| 0 | 36 983 (93.5) | 33 427 (93.4) | 3556 (94.8) |

| 1-2 | 1527 (3.9) | 1403 (3.9) | 124 (3.3) |

| ≥3 | 1024 (2.6) | 953 (2.7) | 71 (1.9) |

| Residence | |||

| Metropolitan | 33 226 (84.0) | 29 788 (83.2) | 3438 (91.7) |

| Nonmetropolitan | 6286 (15.9) | >5984 (>16.7) | >302 (>8.1) |

| Unknown | 22 (0.1) | <11 (<0.03) | <11 (<0.29) |

| Region | |||

| Midwest | 4757 (12.0) | 4554 (12.7) | 203 (5.4) |

| Northeast | 8257 (20.9) | 7067 (19.7) | 1190 (31.7) |

| South | 10 312 (26.1) | 9734 (27.2) | 578 (15.4) |

| West | 16 208 (41.0) | 14 428 (40.3) | 1780 (47.5) |

| Percentile of HRR-level prostate cancer imaging | |||

| <74 | 38 508 (97.4) | 34 827 (97.3) | 3681 (98.1) |

| ≥75 | 1026 (2.6) | 956 (2.7) | 70 (1.9) |

| ICE quintile (ICE values) | |||

| First (−1 to 0.4691) | 7907 (20.0) | 7362 (20.6) | 545 (14.5) |

| Second (0.4692 to 0.7238) | 7907 (20.0) | 7107 (19.9) | 800 (21.3) |

| Third (0.7239 to 0.8411) | 7904 (20.0) | 7037 (19.7) | 867 (23.1) |

| Fourth (0.8413 to 0.9204) | 7910 (20.0) | 7071 (19.8) | 839 (22.4) |

| Fifth (0.9205 to 1) | 7906 (20.0) | 7206 (20.1) | 700 (18.7) |

| Timing of prostate MRI | |||

| No MRI | 66 667 (168.6) | 66 667 (186.3) | 0 |

| Before biopsy | 1841 (4.7) | 0 | 1841 (49.1) |

| After biopsy | 3074 (7.8) | 0 | 3074 (82.0) |

| Diagnosis year | |||

| 2011 | 10 137 (25.6) | 9603 (26.8) | 534 (14.2) |

| 2012 | 7819 (19.8) | 7336 (20.5) | 483 (12.9) |

| 2013 | 7459 (18.9) | 6847 (19.1) | 612 (16.3) |

| 2014 | 6890 (17.4) | 6035 (16.9) | 855 (22.8) |

| 2015 | 7229 (18.3) | 5962 (16.7) | 1267 (33.8) |

| Registry | |||

| San Francisco, California | 1520 (3.8) | 1368 (3.8) | 152 (4.1) |

| Connecticut | 1828 (4.6) | 1542 (4.3) | 286 (7.6) |

| Detroit, Michigan | 2693 (6.8) | 2606 (7.3) | 87 (2.3) |

| Hawaii | 365 (0.9) | 341 (1.0) | 24 (0.6) |

| Iowa | 2064 (5.2) | 1948 (5.4) | 116 (3.1) |

| New Mexico | 815 (2.1) | 775 (2.2) | 40 (1.1) |

| Seattle, Washington | 2518 (6.4) | 2364 (6.6) | 154 (4.1) |

| Utah | 906 (2.3) | 851 (2.4) | 55 (1.5) |

| Atlanta, Georgia | 1327 (3.4) | 1203 (3.4) | 124 (3.3) |

| San Jose, California | 1118 (2.8) | 1038 (2.9) | 80 (2.1) |

| Los Angeles, California | 1713 (4.3) | 1276 (3.6) | 437 (11.7) |

| Rural Georgia | 102 (0.3) | 86 (0.2) | 16 (0.4) |

| Greater California | 7253 (18.3) | 6415 (17.9) | 838 (22.3) |

| Kentucky | 2164 (5.5) | 2093 (5.8) | 71 (1.9) |

| Louisiana | 2975 (7.5) | 2790 (7.8) | 185 (4.9) |

| New Jersey | 6429 (16.3) | 5525 (15.4) | 904 (24.1) |

| Greater Georgia | 3744 (9.5) | 3562 (10.0) | 182 (4.9) |

Abbreviations: HRR, hospital referral region; ICE, Index of Concentration at the Extreme; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Some values are obscured owing to cell sizes less than 11.

Includes American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian and Other Pacific Islander, and unknown race.

Receipt of prostate MRI was associated with multiple patient-level sociodemographic factors, including lower clinical risk (per Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment unit: OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-0.99), younger age (aged 70-74 vs 66-69 years: OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.77-0.90), marital status (not married: OR 0.91; 95% CI, 0.82-1.00), higher educational levels (30%-39% with a high school degree vs <30% with a high school degree: OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.57-0.70), and absence of dual Medicaid eligibility (dual Medicaid eligibility: OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83). At the regional level, lower census tract poverty level (20%-100% impoverished vs <5% impoverished: OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71-0.98), urbanicity (nonmetropolitan vs metropolitan: OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.66-0.86), and region (Northeast vs Midwest: OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 2.80-3.86) were also associated with odds of prostate MRI use.

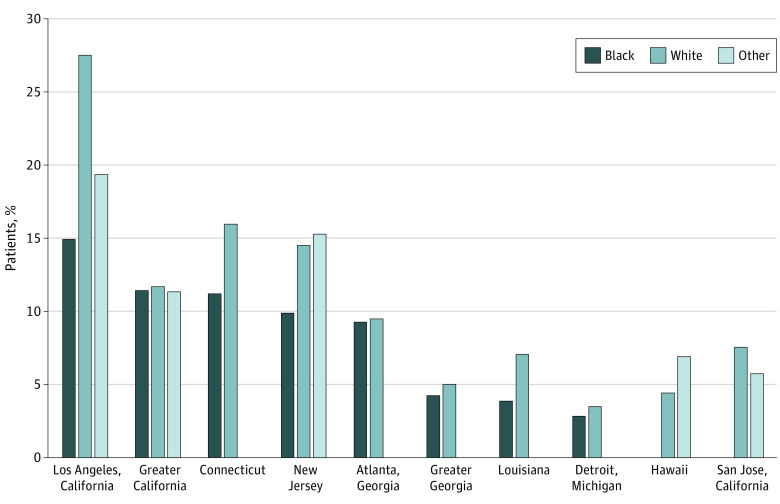

Patients residing in areas with higher levels of racialized residential segregation had lower odds of prostate MRI use. Among those residing in the lowest ICE quintile areas (those with the highest concentration of Black residents relative to White residents), 6.9% of patients received a prostate MRI, compared with 10.1% of those in the second quintile, 11.0% of those in the third quintile, 10.6% of those in the fourth quintile, and 8.9% of those in the fifth quintile. Racial disparity in the use of prostate MRI use varied by SEER registry region. For example, 14.9% of Black patients with prostate cancer received prostate MRI in the Los Angeles registry compared with 27.5 % of White patients. However, in the Atlanta registry, there was a similar use of prostate MRI among Black patients (9.2%) and White patients (9.5%) (Figure 2).

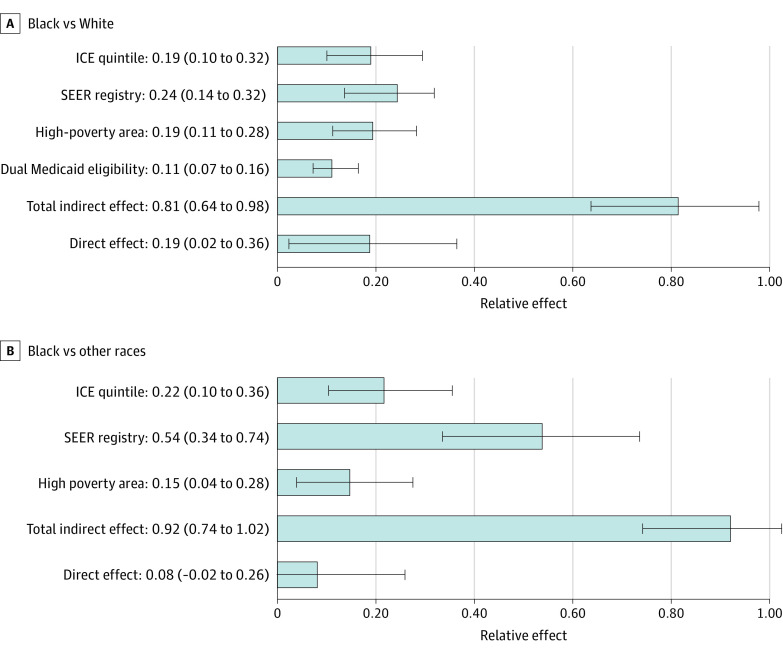

Figure 2. Relative Effect Sizes From the Multiple Mediation Model.

A, Racial disparity between Black and White patients in the use of prostate magnetic resonance imaging. B, Racial disparity between Black and other races in the use of prostate magnetic resonance imaging. Effect sizes of hospital referral region–level prostate cancer imaging were not included owing to values of less than 1%. ICE indicates Index of Concentration at the Extremes; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Based on their associations with race and prostate MRI receipt, SEER region, HRR-level prostate imaging use, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, ICE category, and area-level high poverty met criteria as mediators. Dual Medicaid eligibility did not meet criteria as a mediator in the model comprising patients whose race was defined as Black and patients whose race was defined as other but was included as a covariate. The mediators accounted for 81% (95% CI, 64%-98%) of observed Black vs White racial disparity in prostate MRI (Figure 3). Variation in geography (SEER registry) explained 24% (95% CI, 14%-32%) of the effect of race on prostate MRI use, residence in high-poverty areas accounted for 19% (95% CI, 11%-28%), racial segregation (ICE quintile) accounted for 19% (95% CI, 10%-29%), and dual eligibility for Medicaid accounted for 11% (95% CI, 7%-16%) (Table 2). Hospital referral region–level rates of overall prostate cancer imaging contributed minimally (relative effect, −0.3%; 95% CI, −0.8% to 0.1%). The direct effects of race accounted for 19% (95% CI, 2%-36%) of the observed disparity in prostate MRI use. Similar effects were observed in a separate model examining mediators of disparity in prostate MRI use between patients whose race was identified as Black and patients whose race was identified as other (Table 2).

Figure 3. Proportion of Patients With Prostate Cancer Receiving Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging Surrounding Initial Diagnosis by Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registry Region, Stratified by Race.

Registries with fewer than 11 Black patients receiving prostate MRI were excluded owing to cell size restrictions (rural Georgia; Utah; Iowa; San Francisco, California; New Mexico; Seattle, Washington; and Kentucky).

Table 2. Mediation Analysis Estimations for Racial Disparity in Prostate MRI Receipt.

| Mediator | Log odds (95% CI) | Relative effects (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison of race identified as Black vs White a | ||||

| Direct effects | −0.07 (−0.15 to −0.01) | 0.19 (0.02 to 0.36) | ||

| Indirect effects | −0.28 (−0.33 to −0.22) | 0.81 (0.64 to 0.98) | ||

| Dual Medicaid eligibility | −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.03) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.16) | ||

| High-poverty area | −0.07 (−0.1 to −0.04) | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.28) | ||

| Regional use of prostate cancer imaging | 0.001 (0 to 0.003) | −0.003 (−0.008 to 0.001) | ||

| SEER registry | −0.08 (−0.12 to −0.05) | 0.24 (0.14 to 0.32) | ||

| ICE group | −0.07 (−0.11 to −0.03) | 0.19 (0.10 to 0.29) | ||

| Total | −0.34 (−0.43 to −0.27) | NA | ||

| Comparison of race identified as Black vs other a , b | ||||

| Direct effects | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.006) | 0.08 (−0.02 to 0.26) | ||

| Indirect effects | −0.32 (−0.41 to −0.22) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.02) | ||

| High-poverty area | −0.05 (−0.098 to −0.014) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.28) | ||

| Regional use of prostate cancer imaging | −0.002 (−0.007 to 0) | 0.006 (0 to 0.018) | ||

| SEER registry | −0.19 (−0.28 to −0.10) | 0.54 (0.34 to 0.74) | ||

| ICE group | −0.07 (−0.13 to −0.04) | 0.22 (0.10 to 0.36) | ||

| Total | −0.35 (−0.45 to −0.25) | NA | ||

Abbreviations: ICE, Index of Concentration at the Extreme; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not applicable; SEER, Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results.

Models adjusted for modified Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score.

Dual Medicaid eligibility was not an eligible mediator for this comparison.

Discussion

In this population-level study, we found that Black men with localized prostate cancer were significantly less likely to receive a prostate MRI in the period surrounding their diagnosis. We further developed a mediation model to estimate factors underlying this observed disparity. We found that clinical, sociodemographic, and structural factors, including poverty and racialized residential segregation, mediated most of the observed racial disparity in prostate MRI use. By quantifying the relative contributions of noncancer factors to disparities in prostate cancer imaging, these findings enhance the validity of explanatory constructs that prioritize upstream factors as intermediators of health inequalities.38 This premise is further supported by our finding that cancer risk did not mediate racial disparity, underscoring that the factors associated with imaging use are largely not related to the characteristics of the patient’s disease. By generating greater clarity about proximate mechanisms underlying racial disparity and their relative effects, this work can help inform initiatives to promote more equitable access to new cancer imaging tools.

Geospatial factors mediated the greatest share of racial disparity in prostate MRI use in a manner consistent with racialized geographic polarization in the US. Approximately one-fourth of the Black-White racial disparity in prostate MRI use was attributed to differences in the use of MRI between SEER registry regions. Furthermore, residence in high-poverty areas where prostate MRI use was less common was associated with 19% of the effect of race. These findings strengthen an existing body of evidence that has detailed the ways in which geographic racial segregation contribute to cancer and other health disparities.39,40,41 Geographic polarization favoring the concentration of Black persons in metropolitan areas should be viewed in the historical context of the widespread migration undertaken in response to systemic violence and discrimination in the 19th and 20th centuries.42 The legacies of rapid and socially unsupported demographic changes remain pronounced in prostate cancer, where race-based gaps in survival differ at the level of SEER-registry region.43 Geographic variation could mediate race-based differences in prostate MRI through multiple avenues. For example, prostate MRI practices may conform with broader patterns of disparate screening and preventive care within regions.44 Spatial isolation might also accentuate other structural health inequities associated with economic, environmental, and social conditions.45 Dual eligibility for Medicaid—a status related to disability or low income—explained 11% of the observed disparity, highlighting the interrelatedness of race, unmet social needs, and their downstream consequences. Given the absence of more granular explanatory evidence, evaluations at the patient and health care organization level are needed to better understand the specific pathways that underlie racial disparity in discretionary services, such as prostate imaging.

Racialized residential segregation mediated disparity in prostate MRI use, underscoring the contribution of structural racism to race-based gaps in emerging prostate cancer services. ICE measures, a representation of the extent to which an area’s residents are spatially concentrated by race, explained 19% of the racial disparity in prostate MRI use. The ICE for residential segregation is a proxy for structural racism that has been associated with numerous adverse health outcomes, but, to our knowledge, has not been applied to examine disparities in the use of diagnostic imaging.33 Previous work has noted associations between residential segregation and racial disparity in prostate cancer outcomes, revealing gaps that may extend from earlier-stage diagnosis and increased early treatment for White patients.5 Given the established role of prostate MRI as an enhanced diagnosis and staging tool, our findings provide a theoretical basis for connecting reduced access with disparity in initial assessment.

Our results can help to inform focused efforts to improve equitable access and quality of diagnostic cancer imaging. Greater access to prostate MRI has been championed by practice organizations, such as the American Urological Association, the American College of Radiology, and patient advocacy groups to improve the quality and precision of prostate cancer care; however, tangible plans for action are undefined.46 Through a mediation model, we demonstrate that addressing sources of geographic and structural variation is a strategic initial step for improving equity in prostate cancer imaging. Broader initiatives to elevate the clinical significance of social determinants are also needed to improve cancer health equity.3,47 As a component of these efforts, health care institutions, payers, and professional organizations can undertake multilevel initiatives, such as tracking and responding to patterns of MRI use and other diagnostic cancer services among all patients in their geographic purview.48 These cross-cutting efforts can be aligned with strategies for advancing health equity, such as addressing exclusionary narratives in medicine, improving workforce diversity, and greater recognition of social risk.49

Limitations

There are important limitations of this study. The model that we constructed is inherently constrained by the candidate mediators that were selected for this retrospective analysis. Therefore, we cannot account for factors external to those identified, such as other built environment variables or other manifestations of systemic racism, which introduce the possibility of missed mediation. As a result, our findings should not be viewed as a comprehensive assessment of all the possible mechanisms associated with underlying racial disparity in prostate MRI use. Future studies can more directly address individual domains. Furthermore, we did not incorporate health care factors such as clinician-level patterns or the pervasive narratives of race as a biological construct that could modify selection for prostate MRI. In addition, using data from incident cancer cases, we were unable to adjust for the intensity of screening or overall prostate MRI use among patients as part of the diagnostic workup for prostate cancer. As a result, we cannot account for potential disparity in screening and diagnosis and the detection biases that may result. Last, integrating geographic data at multiple levels can introduce discontinuities in the data as well as spatial autocorrelations that were not fully accounted for in this analysis.50,51

Conclusions

In this population-based cohort study of US adults, using mediation analysis, sociodemographic factors, including geographic variation, poverty, and structural racism, explain most of the observed racial disparity in prostate MRI use among Black and White Medicare beneficiaries with a new diagnosis of prostate cancer. This research suggests that targeted actions to address race-based differences in prostate MRI use should incorporate a focus on spatial factors as well as upstream social determinants of health. In addition, this work highlights the feasibility of identifying quantifying processes that underlie racial disparity and that can be leveraged in other diseases and treatments.

eMethods.

eTable 1. Selection Process for Variables Meeting Conditions for Mediation

eTable 2. Procedure Codes Used to Identify Prostate Imaging Procedures

eReferences.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):211-233. doi: 10.3322/caac.21555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, et al. Association of Black race with prostate cancer–specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):975-983. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson HA, Martin C, O’Neil B, et al. The relative importance of race compared to health care and social factors in predicting prostate cancer mortality: a random forest approach. J Urol. 2019;202(6):1209-1216. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(2):315-332. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulson MR, Helrich SA, Kenzik KM, Dechert TA, Sachs TE, Katz MH. The impact of racial residential segregation on prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. BJU Int. 2021;127(6):636-644. doi: 10.1111/bju.15293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell B, Franco J. HOLC “redlining” maps: the persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://ncrc.org/holc/

- 8.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768-773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs blog. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347/full/

- 10.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahdoot M, Wilbur AR, Reese SE, et al. MRI-targeted, systematic, and combined biopsy for prostate cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):917-928. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould MK, Schultz EM, Wagner TH, et al. Disparities in lung cancer staging with positron emission tomography in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(5):875-883. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821671b6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis L, Canchola AJ, Spiegel D, Ladabaum U, Haile R, Gomez SL. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer survival: the contribution of tumor, sociodemographic, institutional, and neighborhood characteristics. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(1):25-33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(20):2254-2261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palazzo LL, Sheehan DF, Tramontano AC, Kong CY. Disparities and trends in genetic testing and erlotinib treatment among metastatic non–small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(5):926-934. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leapman MS, Wang R, Park HS, et al. Association between prostate magnetic resonance imaging and observation for low-risk prostate cancer. Urology. 2019;124:98-106. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoge C, Verma S, Lama DJ, et al. Racial disparity in the utilization of multiparametric MRI-ultrasound fusion biopsy for the detection of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23(4):567-572. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-0223-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajayi A, Hwang WT, Vapiwala N, et al. Disparities in staging prostate magnetic resonance imaging utilization for nonmetastatic prostate cancer patients undergoing definitive radiation therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2016;1(4):325-332. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology. 2014;25(4):473-484. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanderWeele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Mediation analysis with multiple mediators. Epidemiol Methods. 2014;2(1):95-115. doi: 10.1515/em-2012-0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8)(suppl):IV-3-IV-18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H, Cashin AG, Lamb SE, et al. ; AGReMA group . A guideline for reporting mediation analyses of randomized trials and observational studies: the AGReMA statement. JAMA. 2021;326(11):1045-1056. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidoff AJ, Zuckerman IH, Pandya N, et al. A novel approach to improve health status measurement in observational claims–based studies of cancer treatment and outcomes. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(2):157-165. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooperberg MR, Pasta DJ, Elkin EP, et al. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: a straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173(6):1938-1942. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158155.33890.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation . Report to Congress: social risk factors and performance under Medicare's value-based purchasing programs. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/report-congress-social-risk-factors-performance-under-medicares-value-based-purchasing-programs

- 26.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Data book: beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/data-book-beneficiaries-dually-eligible-for-medicare-and-medicaid-3/

- 27.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471-482. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makarov DV, Soulos PR, Gold HT, et al. Regional-level correlations in inappropriate imaging rates for prostate and breast cancers: potential implications for the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(2):185-194. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger N, Feldman JM, Kim R, Waterman PD. Cancer incidence and multilevel measures of residential economic and racial segregation for cancer registries. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(1):pky009. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256-263. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010-14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788-819. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieger N, Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Coull BA, Hemenway D. Local residential segregation matters: stronger association of census tract compared to conventional city-level measures with fatal and non-fatal assaults (total and firearm related), using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) for racial, economic, and racialized economic segregation, Massachusetts (US), 1995-2010. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):244-258. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0116-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Coull BA, Krieger N. Spatial social polarisation: using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes jointly for income and race/ethnicity to analyse risk of hypertension. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(12):1199-1207. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):2-10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Q, Li B, Scribner RA. Hierarchical additive modeling of nonlinear association with spatial correlations—an application to relate alcohol outlet density and neighborhood assault rates. Stat Med. 2009;28(14):1896-1912. doi: 10.1002/sim.3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Q, Wu X, Li B, Scribner RA. Multiple mediation analysis with survival outcomes: with an application to explore racial disparity in breast cancer survival. Stat Med. 2019;38(3):398-412. doi: 10.1002/sim.7977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Q, Li B. mma: An R package for mediation analysis with multiple mediators. J Open Res Software. 2017;5(1):11. doi: 10.5334/jors.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):339-349. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang PS, Mayer JD, Wakefield J, et al. Trends in sociodemographic disparities in colorectal cancer staging and survival: a SEER-Medicare analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11(3):e00155. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kish JK, Yu M, Percy-Laurry A, Altekruse SF. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer survival by neighborhood socioeconomic status in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014(49):236-243. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sighoko D, Hunt BR, Irizarry B, Watson K, Ansell D, Murphy AM. Disparity in breast cancer mortality by age and geography in 10 racially diverse US cities. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iceland J, Weinberg DH, Steinmetz E; US Census Bureau. Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States 1980-2000. US Government Printing Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fletcher SA, Marchese M, Cole AP, et al. Geographic distribution of racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201839. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, Massetti GM, Peaker B, Richardson LC. Invasive cancer incidence, 2004-2013, and deaths, 2006-2015, in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties—United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(14):1-13. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6614a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:2819372. doi: 10.1155/2017/2819372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American College of Radiology. Prostate MRI model policy. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Advocacy/AIA/Prostate-MRI-Model-Policy72219.pdf

- 47.Hastings KG, Boothroyd DB, Kapphahn K, et al. Socioeconomic differences in the epidemiologic transition from heart disease to cancer as the leading cause of death in the United States, 2003 to 2015: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(12):836-844. doi: 10.7326/M17-0796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216-221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, Wender RC. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: a blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):31-46. doi: 10.3322/caac.21586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krieger N, Waterman P, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Zip code caveat: bias due to spatiotemporal mismatches between zip codes and US Census–defined geographic areas—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1100-1102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chambers BD, Baer RJ, McLemore MR, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Using Index of Concentration at the Extremes as indicators of structural racism to evaluate the association with preterm birth and infant mortality—California, 2011-2012. J Urban Health. 2019;96(2):159-170. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0272-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eTable 1. Selection Process for Variables Meeting Conditions for Mediation

eTable 2. Procedure Codes Used to Identify Prostate Imaging Procedures

eReferences.