This cross-sectional study examines Medicare data to determine trends in prevalence of diagnosis and treatment of diabetic macular edema and vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy among patients 65 years and older.

Key Points

Question

What are 10-year trends in annual prevalence of diagnosis and treatment of diabetic macular edema (DME) or vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) among patients 65 years and older with diabetes who are Medicare Part B fee-for-service beneficiaries?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, from 2009 to 2018, there was a 1.5-fold increase in annual prevalence of diagnosis (2.8% to 4.3%). Annual prevalence of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor injections doubled among those with DME (15.7% to 35.2%) and VTDR with DME (20.2% to 47.6%), while prevalence of laser photocoagulation and vitrectomy in 2018 was less than half that in 2009.

Meaning

These findings show that treatments for DME or VTDR have changed dramatically among Medicare beneficiaries.

Abstract

Importance

While diabetes prevalence among US adults has increased in recent decades, few studies document trends in diabetes-related eye disease.

Objective

To examine 10-year trends (2009-2018) in annual prevalence of Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes with a diagnosis of diabetic macular edema (DME) or vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) and trends in treatment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional study using Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services research identifiable files, data for patients 65 years and older were analyzed from claims. Beneficiaries were continuously enrolled in Medicare Part B fee-for-service (FFS) insurance for the calendar year and had a diagnosis of diabetes on 1 or more inpatient claims or 2 or more outpatient claims during the calendar year or a 1-year look-back period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Using diagnosis and procedure codes, annual prevalence was determined for beneficiaries with 1 or more claims for (1) any DME, (2) either DME or VTDR, and (3) anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections, laser photocoagulation, or vitrectomy, stratified by any DME, VTDR with DME, and VTDR without DME. Racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis and treatment are presented for 2018.

Results

In 2018, 6 960 823 beneficiaries (27.4%) had diabetes; half were aged 65 to 74 years (49.7%), half (52.7%) were women, and 75.7% were non-Hispanic White. From 2009 to 2018, there was an increase in the annual prevalence of beneficiaries with diabetes who had 1 or more claims for any DME (1.0% to 3.3%) and DME/VTDR (2.8% to 4.3%). Annual prevalence of anti-VEGF increased, particularly among patients with any DME (15.7% to 35.2%) or VTDR with DME (20.2% to 47.6%). Annual prevalence of laser photocoagulation decreased among those with any DME (45.5% to 12.5%), VTDR with DME (54.0% to 20.3%), and VTDR without DME (22.5% to 5.8%). Among all 3 groups, prevalence of vitrectomy in 2018 was less than half that in 2009. Prevalence of any DME and DME/VTDR was highest among Hispanic beneficiaries (5.0% and 7.0%, respectively) and Black beneficiaries (4.5% and 6.2%, respectively) and lowest among non-Hispanic White beneficiaries (3.0% and 3.8%, respectively). Among those with DME/VTDR, anti-VEGF was most prevalent among non-Hispanic White beneficiaries (30.3%).

Conclusions and Relevance

From 2009 to 2018, prevalence of DME or VTDR increased among Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries alongside an increase in anti-VEGF treatment and a decline in laser photocoagulation and vitrectomy.

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication of diabetes that results from high levels of blood glucose damaging retinal blood vessels. Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of incident blindness in US adults aged 20 to 74 years.1 Vision-threatening DR (VTDR) includes severe nonproliferative DR (presence of intraretinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, venous beading, or intraretinal microvascular abnormalities) and proliferative DR (presence of neovascularization or vitreous hemorrhage). Diabetic macular edema (DME), swelling in the macula caused by fluid leaking from retinal blood vessels, can occur with any stage of DR.2,3,4 Diabetic retinopathy, VTDR, and DME affect 28.5%, 4.4%, and 3.8%, respectively, of US adults 40 years and older with diabetes.2,5

Risk of developing VTDR is influenced by diabetes duration and glycemic control.5,6,7,8,9 Interventions to increase glycemic control can prevent vision loss.8 Individuals with diabetes are recommended to receive annual dilated eye examinations for early detection and timely treatment of DR.10,11,12,13 The preferred treatment for proliferative DR, panretinal laser photocoagulation (ie, scatter laser surgery),7,14,15 reduces the risk of moderate and severe vision loss by 50% in individuals with severe nonproliferative DR or proliferative DR.8 The standard of care for non–center-involved DME, focal laser photocoagulation surgery,15 reduces the risk of moderate vision loss by 50% to 70% in patients with macular edema.8 In the early 2000s, physicians began using intravitreal injections of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents (ie, aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab) for the treatment of center-involved DME.15 In the last decade, anti-VEGF injections became the first-line treatment for DME because of their efficacy and ease of administration16 and are included in the American Academy of Ophthalmology DR Preferred Practice Pattern.15 A meta-analysis of 24 randomized clinical trials of anti-VEGF therapy in patients with DME and moderate vision loss found that aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab were all more effective than laser photocoagulation for improving vision after 1 year.16 For proliferative DR, 2 studies demonstrated that anti-VEGF injections can be alternatives to panretinal laser photocoagulation.17,18 Other less commonly used treatments for DR include vitrectomy and retinal detachment repair.

Given these changes in DR treatment and the increase in diabetes prevalence among US adults (from 9.8% in 1999-2000 to 14.3% in 2017-2018),19,20 a better understanding of trends in DR complications and treatment could help guide practice recommendations and guidelines. Previous observational studies of DR prevalence are limited by older data. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) last assessed DR in the period 2005 to 2008.2 Medicare administrative claims provide an opportunity to evaluate DR prevalence and treatment among beneficiaries 65 years and older, the population at highest risk of DR.21 Existing studies of DR in Medicare are older and do not capture recent changes in treatment options, such as anti-VEGF injections.22,23,24 In addition, the prevalence of diabetes among Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries 68 years and older increased from 23.3% in 2001 to 32.2% in 2012,25 highlighting the need to examine trends in diabetes complications in this population. In this article, we use new data from the Medicare 100% FFS file to examine 10-year trends in the annual prevalence of Medicare Part B beneficiaries 65 years and older with diabetes who have payment claims for DME or VTDR (hereafter DME/VTDR), the annual prevalence of treatment, and racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence and treatment of DME/VTDR.

Methods

We analyzed 100% of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services research identifiable files from 2009 to 2018 for beneficiaries 65 years and older who were enrolled in Medicare Part B FFS insurance. The analysis excluded beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, which are not included in FFS claims. We restricted the sample to beneficiaries in each year with continuous Part B FFS enrollment for all 12 months. This study used a repeated cross-sections design, rather than following beneficiaries longitudinally, to present the annual prevalence of Medicare beneficiaries with 1 or more claims for DME/VTDR and the annual prevalence of treatment from 2009 to 2018. This research was considered exempt from institutional review board review under 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.101[b][5], which covers Department of Health and Human Services research and demonstration projects that are designed to study, evaluate, or examine public benefit or service programs. Findings of this study are reported in accordance with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Using the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse diabetes flag, beneficiaries were coded with a diabetes diagnosis if they had 1 or more inpatient codes or 2 or more different-day outpatient diagnosis codes (from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, hereafter ICD) on claims during the calendar year or a 1-year look-back period.26 The primary outcome was the annual national crude prevalence of Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries with diabetes and 1 or more claims for DME/VTDR, defined as having an ICD code on a claim indicating a diagnosis of DME or VTDR. Prevalence was calculated as the number of continuously enrolled beneficiaries with diabetes who had 1 or more claims for DME/VTDR in the calendar year divided by the number of continuously enrolled beneficiaries with diabetes in that year. The annual crude national prevalence of DME/VTDR was calculated across the 10 years along with the corresponding prevalence count of beneficiaries.

Because of the emergence of new, effective therapies for DME, we separately present the annual prevalence of beneficiaries with 1 or more claims for DME, which included claims indicating DME alone or combined with any stage of DR (hereafter any DME). Lastly, we calculated the annual prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for non–vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease, characterized as background DR, nonproliferative DR (not otherwise specified), unspecified DR without macular edema, mild nonproliferative DR (without DME), moderate nonproliferative DR (without DME), diabetes with ophthalmic manifestations, and other diabetic ophthalmic complications. eTables 1, 2, and 3 in the Supplement contain ICD diagnosis codes used to define these three groups: DME/VTDR, any DME, and non–vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease.

A secondary outcome was treatment of vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease. eTable 4 in the Supplement contains procedure codes (Current Procedural Terminology and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) used to define 4 treatment types: anti-VEGF injections, laser photocoagulation, vitrectomy, and retinal detachment repair. Across the 10 years, we present the crude annual national prevalence of beneficiaries with diabetes and 1 or more claims for treatment, stratified by treatment type and by the form of vision-threatening disease: (1) any DME, (2) VTDR with DME (hereafter VTDR with DME), and (3) VTDR without DME (hereafter VTDR without DME). eTables 5, 6, and 7 in the Supplement contain the diagnosis codes used to define these groups. For each treatment, we calculated prevalence as the number of continuously enrolled beneficiaries with diabetes and vision-threatening disease who had 1 or more claims for treatment in the calendar year divided by the number of continuously enrolled beneficiaries with diabetes and vision-threatening disease in that year.

An additional analytic aim was to examine differences in the prevalence and treatment of DME/VTDR by race and ethnicity (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and other races and ethnicities, a category that included any race or ethnicity named that did not fit in the preceding list). The Medicare enrollment database contains race and ethnicity information for beneficiaries from the Social Security Administration’s master beneficiary record, and Research Triangle Institute has developed an algorithm to improve the accuracy of this information.27 We present the 2018 crude national prevalence of DME/VTDR, any DME, and the 4 treatment types by each race and ethnicity group. For simplicity, we present the prevalence of the 4 treatments by race and ethnicity among those with a diagnosis of DME/VTDR. We did not provide CIs or perform statistical testing because these data represent 100% of Medicare beneficiaries who met the inclusion criteria. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide (version 9.4; SAS Institute).

Results

Among the 25 396 615 continuously enrolled Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries 65 years and older in 2018, a total of 6 960 823 (27.4%) had a diabetes diagnosis (Table). Approximately half (49.7%) of these beneficiaries were aged 65 to 74 years and half (52.7%) were women. The majority of beneficiaries with diabetes were non-Hispanic White (75.7%) and qualified originally for Medicare by reaching age 65 years (84.5%). Characteristics of the population under study remained stable from 2009 to 2018.

Table. Characteristics of Medicare Part B Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries 65 Years and Older, by Year (2009-2018).

| Characteristics | Year of enrollment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Total FFS population | 24 207 362 | 24 401 537 | 24 551 886 | 24 691 707 | 24 855 992 | 24 790 492 | 24 949 088 | 25 426 301 | 25 443 372 | 25 396 615 |

| Diabetes diagnosis, % | 27.2 | 27.7 | 28.2 | 28.3 | 28.2 | 28.1 | 27.9 | 27.9 | 27.7 | 27.4 |

| Diabetes population, No. | 6 580 117 | 6 752 280 | 6 918 137 | 6 989 689 | 7 007 273 | 6 953 860 | 6 967 485 | 7 085 303 | 7 044 471 | 6 960 823 |

| Sex, % | ||||||||||

| Male | 45.0 | 45.2 | 45.4 | 45.6 | 45.8 | 46.2 | 46.5 | 46.7 | 47.0 | 47.3 |

| Female | 55.0 | 54.8 | 54.6 | 54.4 | 54.2 | 53.8 | 53.5 | 53.3 | 53.0 | 52.7 |

| Age, % | ||||||||||

| 65-74 y | 47.2 | 47.4 | 47.6 | 48.0 | 48.4 | 48.9 | 49.4 | 49.8 | 49.9 | 49.7 |

| 75-84 y | 38.2 | 37.8 | 37.4 | 36.9 | 36.4 | 36.0 | 35.7 | 35.6 | 35.8 | 36.2 |

| ≥85 y | 14.6 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 15.2 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 14.9 | 14.6 | 14.3 | 14.1 |

| Race and ethnicity, % | ||||||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| Black | 10.9 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 10.9 |

| Hispanic | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.6 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 77.3 | 76.9 | 76.5 | 76.3 | 76.1 | 76.2 | 76.2 | 75.8 | 75.6 | 75.7 |

| Other | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Original eligibility, % | ||||||||||

| Age ≥65 y | 86.8 | 86.5 | 86.0 | 85.6 | 85.3 | 85.1 | 84.9 | 84.7 | 84.5 | 84.5 |

| Disability | 12.9 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| ESKD | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Disability and ESKD | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Abbreviations: ESKD, end-stage kidney disease, FFS, fee-for-service.

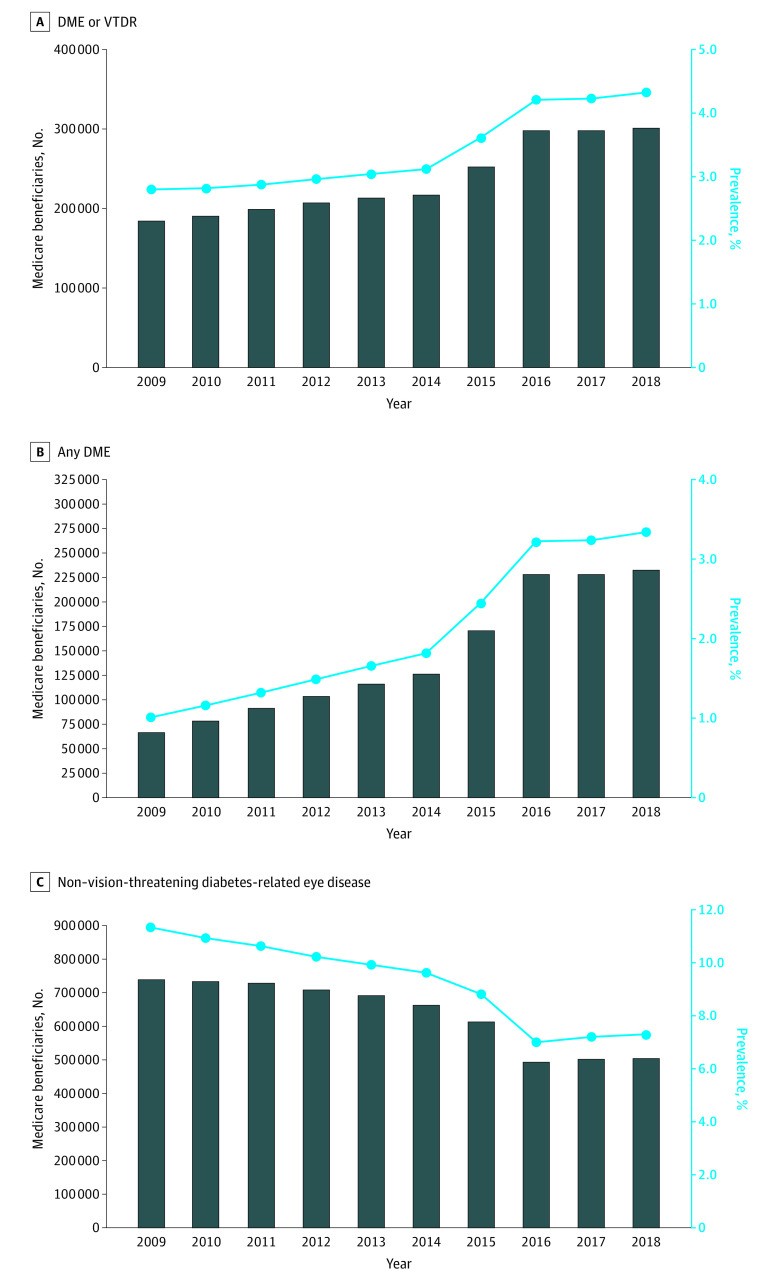

The annual crude national prevalence of Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes who had 1 or more claims for DME/VTDR increased from 2.8% in 2009 to 4.3% in 2018 (Figure 1). The number of beneficiaries with a claim for DME/VTDR increased from 184 520 to 301 550. The separate trendline for any DME shows an increase in prevalence from 1.0% of beneficiaries with diabetes in 2009 to 3.3% in 2018; the number of beneficiaries with a claim for any DME increased from 66 634 to 232 508. Conversely, the prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for non–vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease decreased from 11.3% in 2009 to 7.3% in 2018.

Figure 1. Annual Crude National Prevalence of Medicare Beneficiaries With Diabetes With 1 or More Claims for Diabetes-Related Eye Diseases (2009-2018).

A, Diabetic macular edema (DME)/vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) was defined as diabetic macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (with or without diabetic macular edema), or proliferative diabetic retinopathy (with or without diabetic macular edema). B, Any DME was presented as a trend line (separate from DME/VTDR in A) and was characterized as any diagnosis of DME, by itself or with any stage of diabetic retinopathy. C, Non–vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease was characterized as background diabetic retinopathy, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (not otherwise specified), unspecified diabetic retinopathy without macular edema, mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (without DME), moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (without DME), diabetes with ophthalmic manifestations, or other diabetic ophthalmic complication.

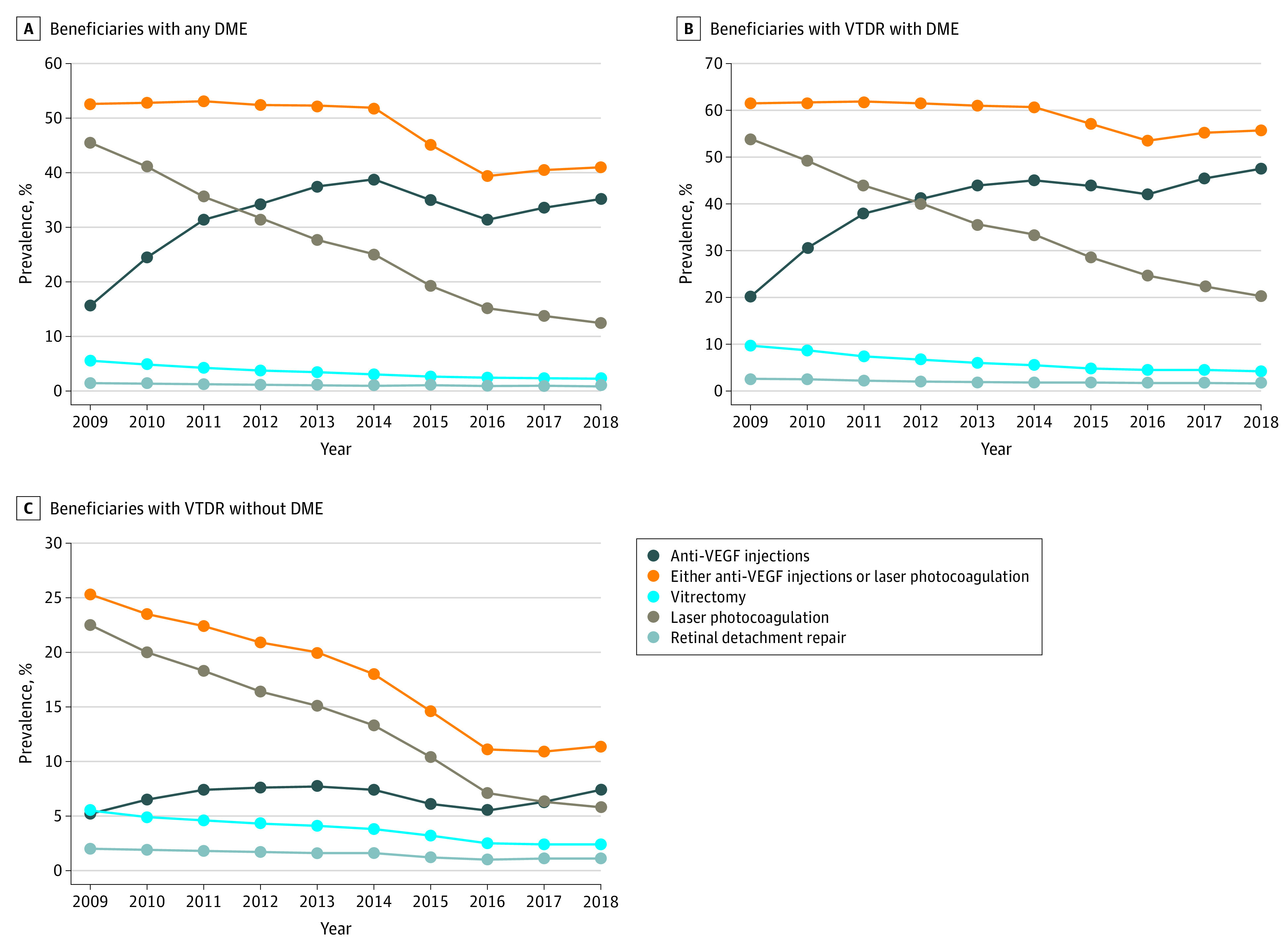

From 2009 to 2018, the annual prevalence of anti-VEGF injections more than doubled among those with any DME (15.7% to 35.2%) and those with VTDR with DME (20.2% to 47.6%) (Figure 2). The increase was smaller among those with VTDR without DME (5.2% to 7.4%). In contrast, the prevalence of laser photocoagulation decreased significantly among those with any DME (45.5% to 12.5%), VTDR with DME (54.0% to 20.3%), and VTDR without DME (22.5% to 5.8%). In each year from 2009 to 2018, more than half of the beneficiaries with VTDR with DME received either anti-VEGF injections or laser photocoagulation. Although vitrectomy and retinal detachment repair were uncommon, among all 3 groups, there was a decline in the prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for these procedures.

Figure 2. Annual Crude National Prevalence of Medicare Beneficiaries With Diabetes and 1 or More Claims for Treatment (2009-2018).

Vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) was defined as severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. DME indicates diabetic macular edema; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

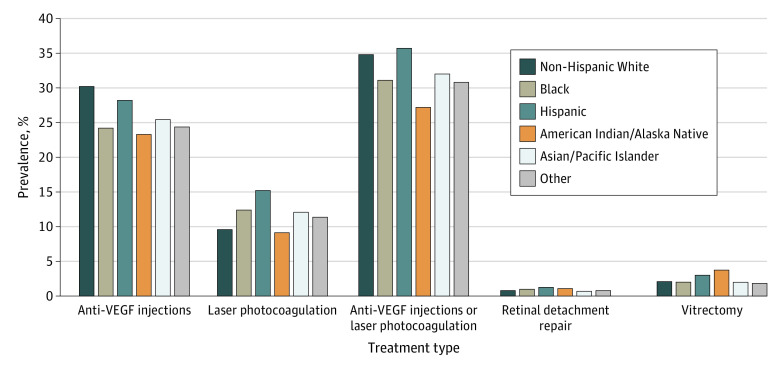

Differences by race and ethnicity were found. The 2018 prevalence of both DME/VTDR and any DME was highest among beneficiaries who were American Indian/Alaska Native (6.0% and 3.8%, respectively), Black (6.2% and 4.5%, respectively), and Hispanic (7.0% and 5.0%, respectively) (Figure 3). Non-Hispanic White beneficiaries had the lowest prevalence of both DME/VTDR (3.8%) and any DME (3.0%). For treatment, the prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for anti-VEGF injections was highest among Hispanic (28.3%) and non-Hispanic White (30.3%) beneficiaries and lowest among beneficiaries who were American Indian/Alaska Native (23.4%), Black (24.3%), or other races and ethnicities (24.6%) (Figure 4). The prevalence of laser photocoagulation was highest among Asian/Pacific Islander (12.2%), Black (12.5%), and Hispanic (15.2%) beneficiaries and lowest among American Indian/Alaska Native (9.3%) and non-Hispanic White (9.7%) beneficiaries. Retinal detachment repair and vitrectomy were infrequent (<4% prevalence) among all racial and ethnic groups.

Figure 3. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the 2018 Crude National Prevalence of Medicare Beneficiaries With Diabetes With 1 or More Claims for Diabetic Macular Edema or Vision-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy (DME/VTDR) or Any DME.

DME/VTDR was defined as DME, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (with or without DME), or proliferative diabetic retinopathy (with or without DME). Presented separately is the prevalence of any DME, characterized as any diagnosis of DME by itself or with any stage of diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 4. Medicare Beneficiaries With Diabetes, Stratified by Racial and Ethnic Group, Who Had 1 or More Claims for Treatment of Diabetes-Related Eye Diseases in 2018, Among Those With Diabetic Macular Edema or Vision-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy (DME/VTDR).

DME/VTDR was defined as DME, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (with or without DME), or proliferative diabetic retinopathy (with or without DME). VEGF indicates vascular endothelial growth factor.

Discussion

From 2009 to 2018, we found a 54% increase in the annual prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for DME/VTDR (from 2.8% to 4.3%) and a 230% increase in the annual prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for any DME (from 1.0% to 3.3%) among Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries 65 years and older with diabetes. During these years, Medicare added 117 000 beneficiaries with an annual claim for DME/VTDR. We observed a steep increase in prevalence between 2014 and 2016, following the 2012 Food and Drug Administration approval of ranibizumab for DME and coinciding with the 2014 approval of aflibercept for DME and the 2015 approval of ranibizumab and aflibercept for DR in patients with DME. This period also coincided with the 2015 transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding, and we cannot discount the possibility that changes in ICD coding contributed to the observed trends. During the 10-year study period, there was a 35% decrease in the annual prevalence of beneficiaries with claims for non–vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease. Although reasons are unknown for the observed increase in vision-threatening disease and decrease in non–vision-threatening disease, these trends could reflect worsening disease due to changes in glycemic control among the Medicare population with diabetes. A recent study found that glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c <7%) among US adults 20 years and older with diabetes declined from 57.4% (95% CI, 52.9%-61.8%) in 2007 to 2010 to 50.5% (95% CI, 45.8%-55.3%) in 2015 to 2018,28 potentially contributing to observed trends. We also cannot discount the possibility that these disease trends reflect changing patterns in screening and diagnosis of diabetes-related eye diseases or in medical coding for treatment.

We observed changes in treatment from 2009 to 2018. Among those with any DME or VTDR with DME, the annual prevalence of beneficiaries who had claims for anti-VEGF injections more than doubled. By 2018, nearly half of all beneficiaries who had VTDR with DME received anti-VEGF injections. This increase in anti-VEGF treatment corresponded to a sharp decline in the use of laser photocoagulation, as clinicians replaced laser photocoagulation in response to studies demonstrating superior efficacy of anti-VEGF injections for DME treatment.16 While the present study did not capture visual acuity outcomes, studies have shown that improvements in visual acuity among patients with DME are superior with anti-VEGF treatment compared with laser photocoagulation,16 and thus, the findings of the present study could translate to substantial improvements in visual acuity in the Medicare population. However, over time, this could result in increased racial and ethnic disparities in visual acuity, given the finding that receipt of anti-VEGF injections was lowest among beneficiaries who were American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, and other races and ethnicities. Procedures for retinal detachment repair and vitrectomy also declined during this period. Reasons for this finding are unknown; however, this trend could have been due to more aggressive treatment of diabetes-related eye diseases during this time period, leading to fewer severe outcomes.

There are few comparable studies examining the prevalence and treatment of DME/VTDR in the Medicare population. One study using Medicare Part B FFS data followed a sample (n = 20 325) of beneficiaries 65 years and older from 1991 to 1999 and found similar increases in the prevalence of vision-threatening forms of DR.24 The prevalence of proliferative DR increased from 2.1% to 3.8%, and the prevalence of DME increased from 0.4% to 2.1%.24 Another study using a nationally representative 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries found that among patients with DME, use of laser photocoagulation decreased from 43% of patients in 2000 to 30% of patients in 2004, whereas use of intravitreal injection increased from 1% to 13% of patients.29 Another study evaluated administrative claims from commercial health insurance and government insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, and Medicare Advantage) for patients with DME and found that the prevalence of receiving anti-VEGF treatments increased from 5.0% of patients in 2009 to 27.1% in 2014.30 The study also found that anti-VEGF treatments, as a proportion of all DME treatments, increased from 11.6% in 2009 to 61.9% in 2014, whereas use of corticosteroids and focal laser procedures decreased from 6.1% to 2.8% and 75.3% to 24.0%, respectively.30 Patients covered by Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and Medicare received 31%, 24%, and 11% fewer anti-VEGF injections, respectively, compared with those with commercial health insurance.30 Other studies have similarly documented exponential growth in the use of anti-VEGF treatment in the last 2 decades, although they are not directly comparable with our study because they included adults 18 years and older using combined data from commercial health insurance and Medicare Advantage31 or used Medicare Part B data but did not distinguish between anti-VEGF used for age-related macular degeneration treatment vs diabetes-related eye diseases.32,33

Our findings on racial and ethnic differences in DME/VTDR prevalence are consistent with those from investigations using data from population-based studies,3 US nationally representative surveys,2,5 and Medicare claims.34 A previous study using the 2011 Medicare 5% claims files found that the prevalence of DR was higher in Asian (12.2%), Black (14.0%), Hispanic (17.3%), and Native American (16.6%) beneficiaries compared with White (10.4%) beneficiaries.34 NHANES data for 2005 to 2008 also demonstrate a higher prevalence of vision-threatening DR among non-Hispanic Black individuals (9.3%) compared with non-Hispanic White individuals (3.2%)2; a similar disparity was documented for DME.5 These differences could be due to earlier age at diabetes diagnosis and longer disease duration among Black and Hispanic persons,35 poorer glycemic control among Black and Hispanic persons with diabetes compared with White individuals,36,37,38 or disparities in the quality of diabetes care experienced by Black and Hispanic patients.39

Clinical reasons for observed racial and ethnic treatment differences are not known. The prevalence of diabetes among Medicare FFS beneficiaries 68 years and older is higher in Asian/Pacific Islander (43.5%), Black (47.4%), and Hispanic (46.3%) individuals compared with White (29.2%) individuals.25 Previous research on management of diabetes among Medicare managed care beneficiaries found disparities in diabetes care, with Black patients less likely to receive hemoglobin A1c screening, eye examinations, and cholesterol screening.40 In addition, physicians’ experiences with the efficacy of different treatment modalities may influence treatment decisions. One recent study examined racial and ethnic differences in the efficacy of anti-VEGF treatment with bevacizumab and found that the percentage of patients with DME who had visual acuity improvement after 3 injections was lower for Black patients (34%) compared with Hispanic (55%) and White (59%) patients.41 However, although racial and ethnic groups compared in this study were similar with respect to baseline hemoglobin A1c, researchers were unable to account for differences in duration of diabetes and DME. Lastly, geographic differences in use of different treatment modalities for diabetes-related eye disease may contribute to racial and ethnic differences in treatment. Studies have documented geographic differences by US Census division in use of anti-VEGF treatment for Medicare beneficiaries with DME,32,42 with the frequency of bevacizumab use highest in the Mountain division and the frequency of ranibizumab use highest in the Mid-Atlantic division.42

In the absence of treatment, an individual who develops proliferative DR has a 50% chance of becoming blind (visual acuity 6/60 [meters] or 20/200 [feet] or less in the better-seeing eye) within 5 years.43,44,45 Prevention of vision loss among patients with diabetes requires better management of diabetes as well as early detection and timely, effective treatment of DR and DME. Although Medicare Part B insurance covers annual eye examinations for beneficiaries with diabetes,46 studies have shown that only about half of Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes have an annual eye examination.47,48,49 Among Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, the prevalence of annual eye examinations is lower among Black (48.9%) and Hispanic (48.2%) beneficiaries compared with non-Hispanic White (55.6%) beneficiaries.47 This lower rate of screening among Black and Hispanic beneficiaries could indicate that the racial and ethnic disparities in DME/VTDR prevalence observed in the present study would be even higher if screening rates were equivalent among racial and ethnic groups.

Limitations

This analysis is subject to several limitations. First, the analysis excludes the 29.5% of Medicare beneficiaries (on average in 2009-2018) enrolled in Medicare managed care plans,50 which could have influenced the prevalence of DME/VTDR diagnoses and treatment. One study in Los Angeles County compared Medicare managed care patients with diabetes with Medicare FFS patients with diabetes and found that those insured by managed care were more likely to have DR and more likely to require treatment.51 Thus, results of the present analysis may not be generalizable to all adults insured by Medicare, and the exclusion of beneficiaries enrolled Medicare Advantage plans may have resulted in lower rates of DME/VTDR diagnoses and treatment. Second, Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries might have multiple insurers, and services reimbursed by a supplemental plan would not be recorded in Medicare claims, thereby underestimating the prevalence of both diagnoses and treatment. Third, the data presented are likely not representative of the American Indian/Alaska Native population because Medicare data do not include care provided by the Indian Health Service. Fourth, not requiring 2 years of continuous enrollment in Medicare Part B FFS for inclusion in the study may have resulted in some misclassification or underestimation of beneficiaries with diabetes. Fifth, in this analysis, we are unable to quantify the effect of switching from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding in October 2015 on the prevalence of diagnoses.

Conclusions

We found that from 2009 to 2018, there was an increase in the annual prevalence of Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries with diabetes who had claims for DME/VTDR, and by 2018, 1 in 25 beneficiaries with diabetes (more than 300 000 people) had vision-threatening disease. Treatment changed over the period, with anti-VEGF injections surpassing laser photocoagulation as the most commonly used treatment for DME/VTDR. We also documented racial and ethnic disparities in prevalence and treatment of vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease in the Medicare population. While the prevalence of DME/VTDR is highest among American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic beneficiaries, non-Hispanic White beneficiaries have the highest annual prevalence of receiving anti-VEGF injections, the contemporary first-line treatment. Future studies could examine trends in these disparities over the last decade.

From 2005 to 2050, it is projected that there will be a nearly 3-fold increase in the United States in the number of people with DR (from 5.5 million to 16.0 million) and vision-threatening DR (from 1.2 million to 3.4 million).52 Better understanding optimal treatment regimens and associated cost-effectiveness is vital, as DR was estimated to cost Medicare FFS $753 million in 2018.53 While anti-VEGF has rapidly become the standard of care for DME and is cost-effective,54 questions regarding the optimal duration of treatment and frequency of injections require further study.7 In addition, future cost-benefit studies could estimate potential savings for Medicare resulting from increased adoption of anti-VEGF treatment and associated effects on disease progression and visual acuity. It is important for future research to examine barriers to eye care and treatment of DME/VTDR, particularly among racial and ethnic minority populations insured by Medicare.

eTable 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define diabetic macular edema or vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (DME/VTDR)

eTable 2. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define any diabetic macular edema (any DME)

eTable 3. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define non-vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease

eTable 4. List of procedure codes (Current Procedural Terminology and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) used to define 4 treatment types for diabetes-related eye disease

eTable 5. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy without diabetic macular edema (VTDR without DME)

eTable 6. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy with diabetic macular edema (VTDR with DME)

eTable 7. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define any diabetic macular edema (any DME)

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein BEK. Vision disorders in diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. National Institutes of Health; 1995:293-338. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou C-F, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005-2008. JAMA. 2010;304(6):649-656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kempen JH, O’Colmain BJ, Leske MC, et al. ; Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group . The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):552-563. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL III, Klein RE, et al. ; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group . Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677-1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varma R, Bressler NM, Doan QV, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(11):1334-1340. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lachin JM, White NH, Hainsworth DP, Sun W, Cleary PA, Nathan DM; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Research Group . Effect of intensive diabetes therapy on the progression of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 diabetes: 18 years of follow-up in the DCCT/EDIC. Diabetes. 2015;64(2):631-642. doi: 10.2337/db14-0930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jampol LM, Glassman AR, Sun J. Evaluation and care of patients with diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1629-1637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1909637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohamed Q, Gillies MC, Wong TY. Management of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298(8):902-916. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varma R, Choudhury F, Klein R, Chung J, Torres M, Azen SP; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group . Four-year incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and macular edema: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(5):752-61.e1, 3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Optometric Association . Evidence-based clinical practice guideline: eye care of the patient with diabetes mellitus. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://aoa.uberflip.com/i/374890-evidence-based-clinical-practice-guideline-diabetes-mellitus

- 11.American Academy of Ophthalmology . Prevent diabetic eye disease in 5 steps. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/top-five-diabetes-steps

- 12.American Diabetes Association . Microvascular complications and foot care. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S88-S98. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong DS, Gottlieb J, Ferris FL III, Klein R. Understanding the value of diabetic retinopathy screening. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(5):758-760. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bressler NM, Beck RW, Ferris FL III. Panretinal photocoagulation for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1520-1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0908432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaxel CJ, Bailey ST, Fawzi A, et al. ; American Academy of Ophthalmology . Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern 2019. Published October 2019. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/diabetic-retinopathy-ppp

- 16.Virgili G, Parravano M, Evans JR, Gordon I, Lucenteforte E. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for diabetic macular oedema: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD007419. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007419.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivaprasad S, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, et al. ; CLARITY Study Group . Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2193-2203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31193-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. ; Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2137-2146. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021-1029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Li X, Wang Z, et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among US adults, 1999-2018. JAMA. 2021;326(8):1-13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Vision and Eye Health Surveillance System. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/vehss/index.html

- 22.Sloan FA, Brown DS, Carlisle ES, Ostermann J, Lee PP. Estimates of incidence rates with longitudinal claims data. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(10):1462-1468. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.10.1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sloan FA, Belsky D, Ruiz D Jr, Lee P. Changes in incidence of diabetes mellitus-related eye disease among US elderly persons, 1994-2005. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(11):1548-1553. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.11.1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee PP, Feldman ZW, Ostermann J, Brown DS, Sloan FA. Longitudinal prevalence of major eye diseases. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(9):1303-1310. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.9.1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andes LJ, Li Y, Srinivasan M, Benoit SR, Gregg E, Rolka DB. Diabetes prevalence and incidence among Medicare beneficiaries: United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(43):961-966. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6843a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse: Condition Categories. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories

- 27.Eicheldinger C, Bonito A. More accurate racial and ethnic codes for Medicare administrative data. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(3):27-42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Trends in diabetes treatment and control in US adults, 1999-2018. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2219-2228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2032271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shea AM, Curtis LH, Hammill BG, et al. Resource use and costs associated with diabetic macular edema in elderly persons. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(12):1748-1754. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moulin TA, Adjei Boakye E, Wirth LS, Chen J, Burroughs TE, Vollman DE. Yearly treatment patterns for patients with recently diagnosed diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3(4):362-370. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parikh R, Ross JS, Sangaralingham LR, Adelman RA, Shah ND, Barkmeier AJ. Trends of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor use in ophthalmology among privately insured and Medicare Advantage patients. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(3):352-358. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkowitz ST, Sternberg P Jr, Feng X, Chen Q, Patel S. Analysis of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injection claims data in US Medicare Part B beneficiaries from 2012 to 2015. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(8):921-928. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel S. Medicare spending on anti-vascular endothelial growth factor medications. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(8):785-791. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez JMS, Bailey RA, Rupnow MFT. Demographic disparities among Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes mellitus in 2011: diabetes prevalence, comorbidities, and hypoglycemia events. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18(4):283-289. doi: 10.1089/pop.2014.0115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang MC, Shah NS, Carnethon MR, O’Brien MJ, Khan SS. Age at diagnosis of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States from 2011 to 2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(11):1537-1539. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saydah S, Cowie C, Eberhardt MS, De Rekeneire N, Narayan KMV. Race and ethnic differences in glycemic control among adults with diagnosed diabetes in the United States. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(3):529-535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(17):1853-1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris MI, Eastman RC, Cowie CC, Flegal KM, Eberhardt MS. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):403-408. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canedo JR, Miller ST, Schlundt D, Fadden MK, Sanderson M. Racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes quality of care: the role of healthcare access and socioeconomic status. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):7-14. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0335-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou AF, Brown AF, Jensen RE, Shih S, Pawlson G, Scholle SH. Gender and racial disparities in the management of diabetes mellitus among Medicare patients. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(3):150-161. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osathanugrah P, Sanjiv N, Siegel NH, Ness S, Chen X, Subramanian ML. The impact of race on short-term treatment response to bevacizumab in diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;222:310-317. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu CM, Wu AM, Greenberg PB, Yu F, Lum F, Coleman AL. Frequency of bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections for diabetic macular edema in Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2018;49(4):241-244. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20180329-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferris FL III, Davis MD, Aiello LM. Treatment of diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(9):667-678. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caird FI, Burditt AF, Draper GJ. Diabetic retinopathy: a further study of prognosis for vision. Diabetes. 1968;17(3):121-123. doi: 10.2337/diab.17.3.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deckert T, Simonsen SE, Poulsen JE. Prognosis of proliferative retinopathy in juvenile diabetics. Diabetes. 1967;16(10):728-733. doi: 10.2337/diab.16.10.728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Eye exams (for diabetes). Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/eye-exams-for-diabetes

- 47.Lundeen EA, Wittenborn J, Benoit SR, Saaddine J. Disparities in receipt of eye exams among Medicare Part B Fee-for-Service beneficiaries with diabetes: United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1020-1023. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee PP, Feldman ZW, Ostermann J, Brown DS, Sloan FA. Longitudinal rates of annual eye examinations of persons with diabetes and chronic eye diseases. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(10):1952-1959. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00817-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloan FA, Brown DS, Carlisle ES, Picone GA, Lee PP. Monitoring visual status: why patients do or do not comply with practice guidelines. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(5):1429-1448. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00297.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Total Medicare enrollment: total, original Medicare, and Medicare Advantage and other health plan enrollment, calendar years 2009-2018. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics

- 51.Brown AF, Jiang L, Fong DS, et al. Need for eye care among older adults with diabetes mellitus in fee-for-service and managed Medicare. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(5):669-675. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.5.669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saaddine JB, Honeycutt AA, Narayan KMV, Zhang X, Klein R, Boyle JP. Projection of diabetic retinopathy and other major eye diseases among people with diabetes mellitus: United States, 2005-2050. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(12):1740-1747. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wittenborn JS, Gu Q, Erdem E, et al. The prevalence of diagnosis of major eye diseases and their associated payments in the Medicare Fee-for-Service program. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. Published online September 6, 2021. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2021.1968006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein JD, Newman-Casey PA, Kim DD, Nwanyanwu KH, Johnson MW, Hutton DW. Cost-effectiveness of various interventions for newly diagnosed diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(9):1835-1842. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define diabetic macular edema or vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (DME/VTDR)

eTable 2. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define any diabetic macular edema (any DME)

eTable 3. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define non-vision-threatening diabetes-related eye disease

eTable 4. List of procedure codes (Current Procedural Terminology and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) used to define 4 treatment types for diabetes-related eye disease

eTable 5. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy without diabetic macular edema (VTDR without DME)

eTable 6. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy with diabetic macular edema (VTDR with DME)

eTable 7. ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes used to define any diabetic macular edema (any DME)