Abstract

Mitochondria play important roles in multiple aspects of viral tumorigenesis. Mitochondrial genomes contribute to the host’s genetic background. After viruses enter the cell, they modulate mitochondrial function and thus alter bioenergetics and retrograde signaling pathways. At the same time, mitochondria also regulate and mediate viral oncogenesis. In this context, oncogenesis by oncoviruses like Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Human papilloma virus (HPV), Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) will be discussed.

Keywords: mitochondria, oncovirus, HBV, HCV, HPV, HIV, EBV

Introduction

According to the latest survey, over 10 percent of human tumors are caused by viral infections [1]. Viruses that transform cells into tumors are called oncoviruses, which are one of the three major carcinogenic factors. The pathogenesis of oncoviral oncogenesis includes: entry of the virus into a cell, synthesis and assembly of oncovirus into the host cell, spread of the virus from infected cells to healthy cells and accumulation of oncogenic changes within the infected cells. Recent studies have implicated mitochondria in multiple aspects of oncoviral oncogenesis [2, 3].

Mitochondria are membrane-enclosed organelles that are ubiquitous in eukaryotic cells. They also possess their own genomes, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) contributes to the genetic background of host cells. On the other hand, the biogenesis, distribution and functions of mitochondria are modulated by internal and external stimuli including viruses, and at the same time, mitochondria mediate the viral pathways as well as antiviral immunity [4].

As part of the process to take control of host cells, oncoviruses modulate mitochondrial functions and bioenergetics by altering mitochondrial pathways, including regulating the production of ATP directly through affecting the assembly of respiratory complexes [74], affecting cell death/survival through participating mitochondrial apoptosis pathways, and even causing mitochondrial damage through over-production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [13, 34, 57, 60, 74, 77, 102].

At the same time, mitochondria have been shown to be a double-edged sword in viral tumorigenesis. On the one hand, mitochondria may promote the invasion of the oncovirus [20, 58, 75, 101] and facilitate the formation and development of tumors by incorporating viral proteins into the mitochondrial system and modulating retrograde tumorigenesis pathways [11, 33, 57, 71, 96]. On the other hand, mitochondria can also meditate the termination of viral infection via activating immune responses [17, 37] and initiating apoptosis [38, 59, 69, 77].

In this review, we will discuss the interactions between mitochondria and oncoviruses in the context of tumorigenesis. In particular, we will summarize the relevant current research with common human carcinogenic viruses, with HBV, HCV, HPV, HIV and EBV as examples.

1. HBV

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus with a diameter of 42 nm. It contains a double stranded circular DNA [5]. HBV belongs to the hepadnaviridae virus family. It is the major etiological agent for hepatitis. A chronic infection with HBV is the major risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common malignant liver tumor with the highest mortality rate [6].

The HBV genome is about 3.2 kb, and it encodes 4 overlapping open reading frames designated as S (pre-S1, pre-S2 and S region), C (pre-core and core region), P and X [7]. HBx protein, encoded by HBX, contains 154 amino acids [8]. HBx has been closely associated with HBV-induced oncogenesis in the host cells in multiple ways including the regulation of transcription, signal transduction, cell cycle progress, protein degradation, apoptosis and chromosomal stability [9, 10].

HBx protein targets to the mitochondrial outer membrane [11]. The seven amino acid residues at the c-terminal, and Cys115 in particular, are essential for such translocation [12]. The integration of HBx into the mitochondrial outer membrane induces ROS overproduction and mtDNA oxidative damage [13]. In addition, HBx binds cytochrome c oxidase III (COX III) at the inner mitochondrial membrane [14], and up-regulates the expression of COX III [15]. HBV also activates mitochondrial fission, mediated by stimulating phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein (Drp1) at Ser616, and leads to mitochondrial perinuclear clustering [16].

Mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), located at the mitochondrial outer membrane, is an adaptor molecule downstream of RIG-I and MDA5, which detect intracellular dsRNA produced during viral replication, to coordinate pathways leading to induction of antiviral cytokines, and is thus critical for the innate immunity [17]. Alternatively, MAVS can also cause cell death by increasing the level of voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC1), promoting the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, and eventually inducing cell apoptosis [18]. HBx weakens the antiviral response of the innate immune system by enhancing ubiquitination of MAVS lysine at position 136 [19].

The mitochondrial haplotype constitutes the genetic background for host cells invaded by HBV. A comprehensive study on peripheral blood, tumor and/or adjacent non-tumor tissue from 49 HBV-HCC patients and 38 normal people revealed that people with mtDNA haplogroup M may have increased likelihood of onset of HCC [20].

On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that high cytosolic calcium is essential for HBV DNA replication [21], which involves HBx-mediated activation of Pyk2/ FA kinase and JNK- and MAPK-associated signal transduction pathways [22]. Mitochondrial calcium uptake plays an important role in sustaining elevated levels of cytosolic calcium [23, 24]. In association with mitochondrial permeability transition pore, HBx elevates mitochondrial dependent calcium signaling and stimulates HBV replication [25, 26].

2. HCV

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus with a diameter of 55–65 nm. It belongs to the family of flaviviridae [27]. It is estimated that 3% of the world’s population is infected with HCV, and most of them are unidentified [28]. Like HBV, HCV is also a major risk factor for HCC. The incidence of HCC with HCV is increasing in many countries including the United States [29].

HCV has a 9.6 kb genome, composed of 5’ and 3’ non-translated regions flanking an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a large polyprotein. The HCV genome encodes 10 individual membrane-associated viral proteins which are divided into structural proteins including core protein, envelope 1 (E1) and envelope 2 (E2), and non-structural proteins, including p7 polypeptide, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B proteins [30]. HCV core protein, a component of the viral nucleocapsid, plays a critical role in virus growth and differentiation [31]. NS3 complex with NS4A, in the form of the NS3–4A polyprotein, acts as a cofactor of the proteinase. NS4B protein induces the formation of a membranous web which facilitates the replication, assembly and release of HCV. NS5A was reported to cause aberrant and persistent G2/M-phase entry, thereby sustaining proliferative signaling [32].

The HCV core protein localizes both to ER and the mitochondrial outer membrane via a region spanning amino acids 112 to 152 [33]. The core protein induces a specific inhibition of complex I, which adapts mitochondria for hypoxia and enhances ROS production at the same time [34]. Meanwhile, the core protein facilitates ER Ca2+ release and increases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Such calcium signaling modulation increases mitochondrial ROS production and mitochondrial permeability transition as well as decreasing MMP [35].

HCV infection has also been shown to stimulate mitophagy through up-regulating Parkin and PINK1 proteins. It also triggers Parkin translocation to mitochondria and induces mitochondrial perinuclear clustering [36].

The NS3 and NS4A complex NS3–4A protein, a serine protease, inhibits MAVS by cleaving it from the outer mitochondrial membrane and preventing the formation of MAVS signaling complex for antiviral functions [37]. In addition, HCV NS4B initiates the disruption of MMP and release of cytochrome c which in turn activates the caspase cascade and induces apoptosis [38]. NS5A modulates apoptosis by regulating cytochrome c and Bax [39].

3. HPV

The Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is small, double stranded circular DNA virus with a diameter of 45–55 nm [40]. It has been well established that genital tract epithelial infection with high-risk types of HPV causes cervical cancer (CC) [41]. At the same time, high-risk HPV DNA has also been detected in 99.7% of CC patients [42]. HPV belongs to the papillomavirus family, of which over 170 genotypes have been characterized [40]. HPV16 and 18 is the most common high-risk HPV [43, 44, 45].

The HPV genome is about 8.0 kb, and it encodes 3 overlapping open reading frames designated as long control region (LCR), early genes region (encoding early regulatory proteins, such as E2, E4, E6, and E7), and late genes region (encoding capsid proteins L1 and L2). E6 [46] and E7 [47] are essential for the production of HPV DNA synthesis proteins. In HPV-associated CC, E6 and E7 are always expressed [48, 49], while E2 and E4 are not expressed [50, 51]. There is also a spliced mRNA, E1Ê4, which encodes five amino acids from the E1 ORF spliced to the protein encoded by the E4 ORF, which binds and collapses the cytokeratin network and facilitates release of the virus from cells [52].

Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is essential for mitochondrial transcription and replication [53, 54]. E2 protein could enhance mitochondrial biogenesis by up-regulating TFAM interacting protein P32 or gC1qR [55, 56]. P32/gC1qR, which localizes in the mitochondrial matrix near the nucleoid associated with TFAM, is also an essential RNA-binding protein for mitochondrial translation [56]. It was also reported that HPV 18 E2 interacted with repiratory chain directly and increased release of mitochondrial ROS, which correlateed with stabilization of HIF-1α and increased glycolysis. [57].

The impact of mtDNA haplogroup on CC has been investigated with 187 CC patients and 270 normal people in Mexico City. It was reported that people carrying mtDNA haplogroup B2 exhibited an increased risk of CC among the Mexican population [58].

HPV16 E1Ê4 protein binds to mitochondria, especially in cells lacking cytokeratin. E1Ê4 induces the detachment of mitochondria from microtubules, establishing a single large mitochondrial cluster adjacent to the nucleus. The translocation of mitochondria results in reduction of MMP and induces apoptosis [59]. Meanwhile, sustained over-expression of E6 in cervical carcinoma cells increases ROS production and mitochondrial membrane polarization, leading to apoptosis [60].

4. HIV

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), an RNA lentivirus, belongs to a subgroup of retroviruses, and is composed of two copies of positive single-stranded RNA with a diameter of about 120 nm. HIV infects the human immune system, in particular helper T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, establishing immunity destruction, promoting a variety of dysfunctions and the indefinite proliferation of cells [61]. The average survival time after HIV-1 infection is about 10 years and long-term HIV infections can give rise to shingles, tuberculosis, pneumonia, encephalitis and various types of cancers, leading to AIDS [62]. There are two major species of HIV, HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is more virulent, and is the leading cause of HIV infections globally [63].

The HIV-1 genome is about 9.7 kb which carries 9 genes that encode 19 proteins. These genes include 3 encoding structural proteins gag, pol, and env, 3 regulatory genes tat, rev, nef and 3 proteins controlling virus maturation, assembly and release such as vif, vpu and vpr [64]. HIV-1 surface envelope glycoprotein 120 (gp120) encoded by env, binds to the CD4 glycoprotein and chemokine receptors on the host cell surface, initiating fusion of the virus and the host cell membrane [65]. The Vpr protein arrests cell division at G2/M [66]. In addition, the long terminal repeats (LTRs), a promoter region that mediates the expression of almost all of the HIV-1 proteins, is indispensable for HIV-1 expression and infection [67].

The MPTP consists of 3 major components including the voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC) in the mitochondrial outer membrane, cyclophilin D in the mitochondrial matrix and adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) in the mitochondrial inner membrane [68]. Upon entry into the target cell, the C-terminal peptides of Vpr from HIV-1 bind to ANT, converting MPTP from a normal transporter into a pro-apoptotic pore. This transition is achieved by reducing MMP via Ca2+ influx into mitochondria, thus releasing apoptogenic proteins such as cytochrome c [69]. Mitochondria constantly undergo fusion and fission to maintain their proper function and morphology. Mitofusin-2 (Mfn2), a GTPase embedded in the outer mitochondrial membrane, is an essential component for mitochondrial fusion [70]. Vpr also targets Mfn2 and reduces its protein level. The reduction of Mfn2 damages the integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane, and induces a progressive loss of MMP and mitochondrial deformation [71].

Cxc Chemokin Receptor 4 (CXCR4), a member of the G protein-coupled receptor family, mediates HIV infection of CD4+ T cells [72]. HIV gp120 protein binds CXCR4 to form the complex gp120-CXCR4, and this complex in turn binds mitochondria to initiate mitochondrial membrane depolarization and release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, thus setting off a cascade of caspase activation [73]. It was also reported that HIV-1 infection blocked the expression of complex I subunit NDUFA6 protein, and thereby decreased the activity of complex I directly. The inhibition of complex I in turn enhanced ROS production and decreased MMP and ATP production as well [74].

A study of 1833 patients infected with HIV-1 revealed that mtDNA haplogroup J and U5a posed the most significant risk for AIDS. On the other hand, mtDNA haplogroup Uk, H3 and IWX were identified as being protective against infection of AIDS [75].

As for mitochondrial participation in HIV-1 carcinogenesis, it has been shown that stimulating generation of ROS activates NF-kappa B which further upregulates the HIV-1 related gene expression through HIV-1-LTRs. As a result, various oncogenic changes accumulate which in turn triggers proliferation of infected cells [76]. On the other hand, the high level of ROS in the mitochondrial matrix significantly raises the mutation rate of mtDNA. Over-production of ROS has also been implicated in the activation of mitochondrial glutaminase, and induction of the glutamate-mediated apoptosis pathway in the neuronal system [77].

5. EBV

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a double helix DNA virus with a diameter of 122–180 nm which was first identified in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells [78]. EBV belongs to the human herpes virus type 4 (HHV-4), and B lymphocytes and epithelial cells are the main targets for its infection [79]. There are many EBV associated diseases, such as infectious mononucleosis, lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) [80]. Among these, the most common malignant otolaryngic tumor is NPC, which has the highest mortality rate. The first indication of the implication of EBV in NPC was detection of its significantly high antibody titer in NPC patients [81]. Later, EBV DNA was also found in NPC patients [82]. Now clinically, EBV DNA is widely used to monitor the progression and recurrence of NPC [83, 84], and it is also recognized as a screening tool in research as well as a risk stratification marker in development of therapies [85].

EBV has a double-stranded, circular 172 kb genome which encodes more than 90 proteins [79]. Among these, the latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) plays an indispensable role in oncogenesis. LMP1 has been associated with a variety of important cancer-related pathways, involving NF-kB [86, 87, 88], AP-1 [88], STAT [86] and JNK [89]. Latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) induces a number of pathways that promote malignant cell growth through promoting metastasis and inhibiting differentiation [90]. Zta (BZLF1 or EB1) is an immediate-early protein which is expressed at the early stage of EBV infection. It is a DNA binding protein belonging to the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family [91]. It has been shown that Zta regulates the expression of transforming growth factor and fatty acid synthase genes [92, 93] and is essential for cell cycle progression [94].

mtDNA replication is initiated by transcription-mediated priming facilitated by mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein (mtSSB). mtSSB is a tetramer composed of four 16 kDa subunits and binds to mitochondrial DNA at the transcription and replication initiation area [95]. Zta targets mtSSB and mediates the translocation of mtSSB from mitochondria into the nuclear compartment. It thus inhibits mtDNA replication, and decreases mtDNA copy number [96]. The mitochondrial genome is also considered to be one of the genetically susceptible areas in NPC [97, 98]. Patients with NPC showed a high frequency of mutation at mtDNA np16362 [99].

An epidemiologic study was carried out in south China where the NPC incidence is much higher than in the rest of the world [100]. The impact of mtDNA haplogroup on NPC incidence was investigated in 201 NPC patients with matched controls. It was reported that patients with haplogroup R9, and its sub-haplogroup F1 in particular, exhibited the most aggressive progression of NPC [101].

EBV infection enhances the production of ROS. ROS in turn regulate cytoskeleton rearrangements and induce mitophagy and autophagy, and such regulation is essential for tumorigenesis and metastasis. Peroxiredoxin-3 (PRDX3) is an antioxidant mitochondrial protein [102]. Inhibiting PRDX3 expression enhances metastasis with an increased mobility potential [103]. In addition, LMP2A-mediated Notch pathway enhances mitochondrial fission by elevating dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which also promotes cellular migration [104].

6. Summary

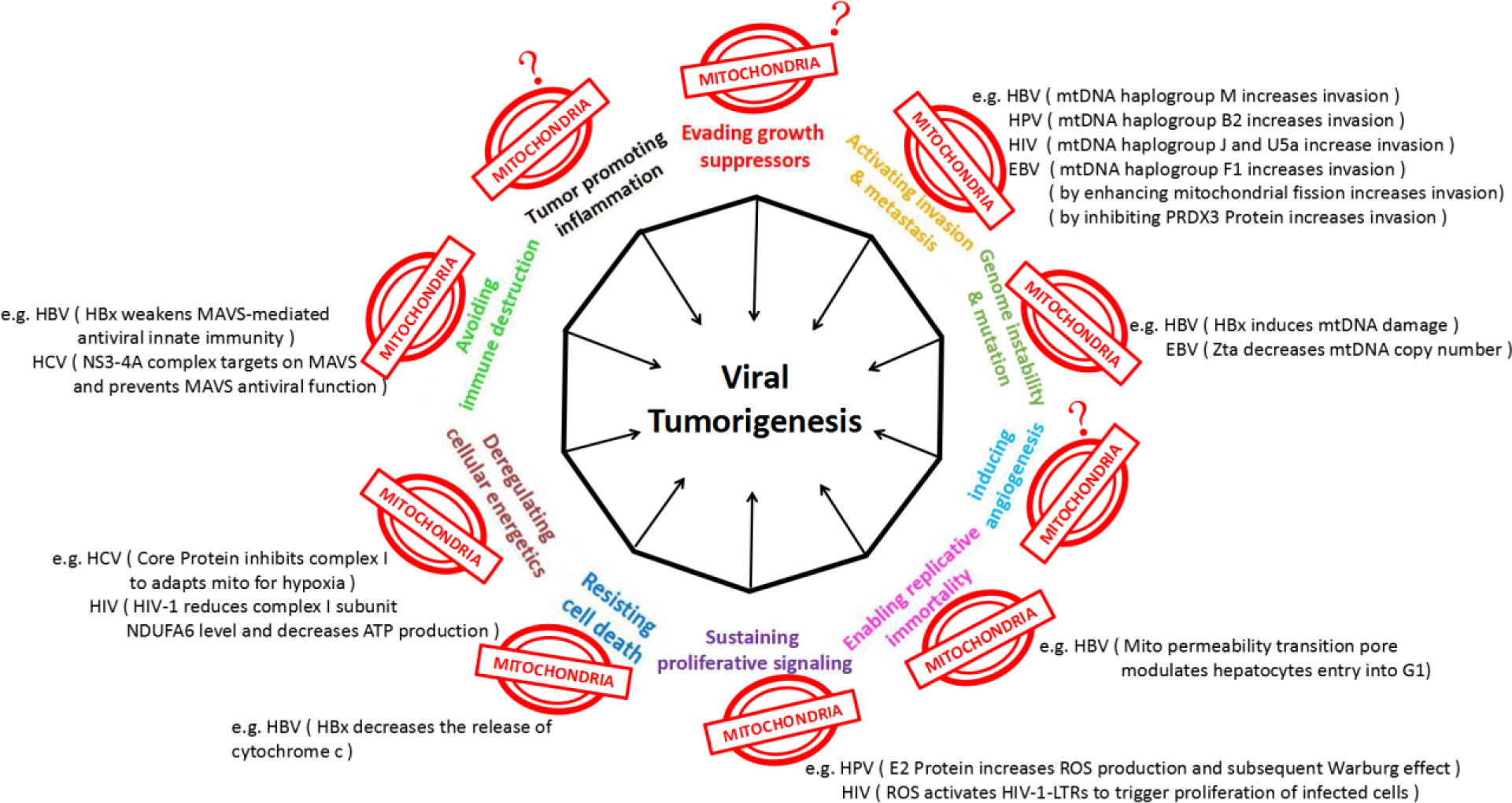

It is well-accepted that tumorigenesis including viral tumorigenesis including ten important hallmarks: evading growth suppressors, activating invasion & metastasis, genome instability & mutation, inducing angiogenesis, enabling replicative immortality, sustaining proliferative signaling, resisting cell death, reregulating cellular energetics, avoiding immune destruction, and tumor promoting inflammation [3]. As we discussed in previous sections, mitochondria were reported involved in at least seven of them in 5 common oncoviruses covered in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mitochondria may mediate the pathogenesis of viral oncogenesis.

Virally induced cell responses are color coded according to the hallmarks of cancer to which they correspond. The figure is adapted from the review of Hanahan and Weinberg (2011) [3]. We summarize the recent studies which implicated mitochondria in multiple aspects of viral tumorigenesis, including activating invasion & metastasis, genome instability & mutation, enabling replicative immortality, sustaining proliferative signaling, resisting cell death, deregulating cellular energetics, and avoiding immune destruction. Mitochondrial influence on other three viral tumorigenesis processes have not yet reported in these common viruses discussed here.

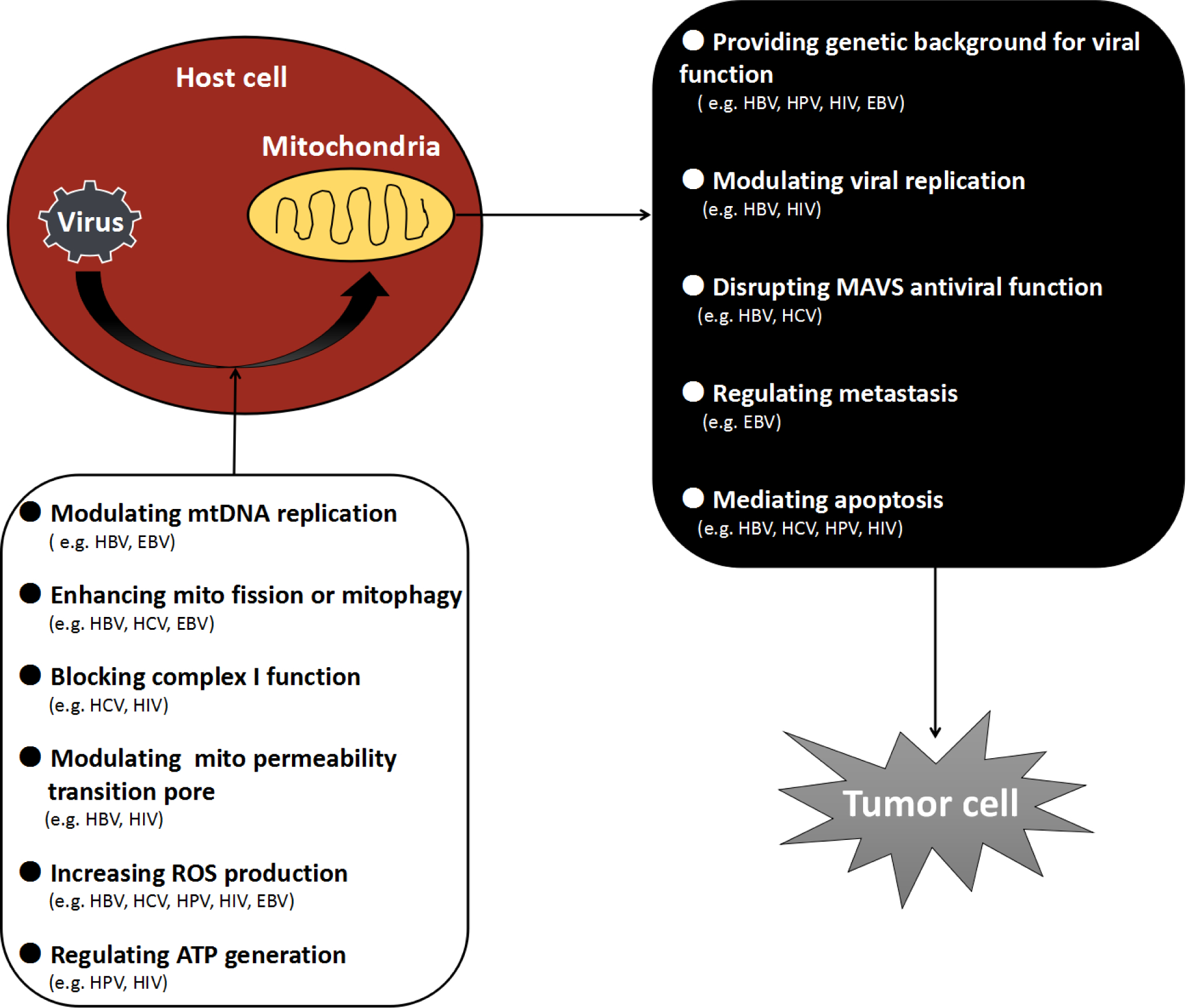

Mitochondria are ubiquitous organelles in eukaryotic cells whose primary role is to generate energy supplies in the form of ATP through oxidative phosphorylation. Recent studies have also shown that mitochondria play a central role in modulating cell growth, host immune response and apoptosis [105, 106, 107]. They are in essence the major cellular hub for bioenergetics, biosynthesis and signal transduction. Human viral oncogenesis often involves persistent infections and overcoming resistance by the host’s immune reactions. Taking control of mitochondria and then integrating mitochondrial pathways are the central goals to achieve, first for viral survival and replication and ultimately for viral oncogenesis. We have discussed viral-mitochondrial interactions with 5 major oncoviruses as summarized in Figure 2. Such interactions certainly go beyond these common viruses. With human T lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), p13II protein targets the mitochondrial inner membrane where it produces a membrane potential-dependent influx of potassium, leading to mitochondrial swelling and fragmentation, and altered mitochondrial calcium uptake [108]. The C-terminal peptides of F1L protein from vaccinia virus (VACV or VV) bind to mitochondria and interfere with apoptosis by inhibiting the loss of MMP [109] and inhibiting apoptosis [110]. The vMIA protein of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) binds Bax to form a vMIA-Bax complex which blocks Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization [111]. The UL12.5 protein of Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) targets onto mitochondria to induce the rapid and complete degradation of host mitochondrial DNA [112].

Figure 2. Virial regulation on mitochondria leading to tumorigenesis.

Mitochondrial dysfunction happens when viruses invade the host cells, which cause a series of events, ultimately induce tumorigenesis.

Although the roles of viral infection in mitochondrial modulation of cancer occurrence and development have been recognized for long time, investigation of the interactions between oncoviruses and mitochondria is still in its infant stage. This is partially due to the limited animal models and unsophisticated analysis systems presently available for such studies. The lack of synergetic discussions among scientists in the relevant fields of mitochondrial biology, virology and cancer biology also hinders the scientific progress. With successful overcoming these obstacles, we anticipate the following progresses in the near future: 1) a comprehansive understanding how mitochondrial DNA haplogroup contribute to the occurrence and development of oncoviral tumroigenesis; 2) identification of mitochondrial biomarkers for oncoviral oncogenesis in serveral prevalent cancers; 3) development of effective medicines for oncoviral oncogenesis targeting direct or indirect on mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, mitochondrial mediated apoptosis, mitophagy and mitochondrial mediated immunity. A better understanding of interactions between mitochondria and oncoviruses in the context of tumorigenesis will centainly provide unique opportunities for prevention and intervention of oncogenesis.

Highlights:

Oncoviruses regulate the mitochondrial function of infected cells.

Mitochondria modulate oncoviral oncogenesis.

Exploring interactions between viruses and mitochondria will provide novel insights into mitochondrial biology and oncoviral oncogenesis.

Acknowledgements

Research in authors’lab has been supported by grants from the Owens Medical Foundation and National Institutes of Health [grant number: R01 GM109434)] to Yidong Bai. Shasha Gong is supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China 81500804.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

None declared.

Yidong Bai, for all the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Plummer M, Martel CD, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Franceschi S, Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis, Lancet Glob Health, 4 (2016) e609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mesri EA, Feitelson M, Munger K, Human Viral Oncogenesis: A Cancer Hallmarks Analysis, Cell Host Microbe, 15 (2014) 266–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hanahan D and Weinberg RA, Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation, Cell, 144 (2011) 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Koshiba T, Mitochondrial-mediated antiviral immunity, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1833 (2013) 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Howard CR, The biology of hepadnaviruses, J Gen Virol, 67 (1986) 1215–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Lancet, 379 (2012) 1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Neuveut C, Wei Y, Buendia MA, Mechanisms of HBV-related hepatocarcinogenesis, J Hepatol, 52 (2010) 594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ma NF, Lau SH, Hu L, Xie D, Wu J, Yang J, Wang Y, Wu MC, Fung J, Bai X, Tzang CH, Fu L, Yang M, Su YA, Guan XY, COOH-terminal truncated HBV X protein plays key role in hepatocarcinogenesis, Clin Cancer Res, 16 (2008) 5061–5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kim CM, Koike K, Saito I, Miyamura T, Jay G, HBx gene of hepatitis B virus induces liver cancer in transgenic mice, Nature, 351 (1991) 317–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Decorsière A, Mueller H, van Breugel PC, Abdul F, Gerossier L, Beran RK, Livingston CM, Niu C, Fletcher SP, Hantz O, Strubin M, Hepatitis B virus X protein identifies the Smc5/6 complex as a host restriction factor, Nature, 531 (2016) 386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Clippinger AJ and Bouchard MJ, Hepatitis B virus HBx protein localizes to mitochondria in primary rat hepatocytes and modulates mitochondrial membrane potential, J Virol, 14 (2008) 6798–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li SK, Ho SF, Tsui KW, Fung KP, Waye MY, Identification of functionally important amino acid residues in the mitochondria targeting sequence of hepatitis B virus X protein, Virology, 381 (2008) 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jung SY, Kim YJ, C-terminal region of HBx is crucial for mitochondrial DNA damage, Cancer Lett, 331 (2013) 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang XZ, Li D, Tao QM, Lin N, Chen ZX, A novel hepatitis B virus X-interactive protein: cytochrome C oxidaseⅢ, J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 21 (2006) 711–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zou LY, Zheng BY, Fang XF, Li D, Huang YH, Chen ZX, Zhou LY, Wang XZ, HBx co-localizes with COXⅢin HL-7702 cells to upregulate mitochondrial function and ROS generation, Oncol Rep, 33 (2015) 2461–2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim SJ, Khan M, Quan J, Till A, Subramani S, Siddiqui A, Hepatitis B Virus Disrupts Mitochondrial Dynamics: Induces Fission and Mitophagy to Attenuate Apoptosis, PLoS Pathog, 9 (2013) e1003722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang QX, Chen ZJ, MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response, Cell, 146 (2011) 448–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Guan K, Zheng Z, Song T, He X, Xu C, Zhang Y, Ma S, Wang Y, Xu Q, Cao Y, Li J, Yang X, Ge X, Wei C, Zhong H, MAVS regulates apoptotic cell death by decreasing K48-linked ubiquitination of voltage-dependent anion channel 1, Mol Cell Biol, 33 (2013) 3137–3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wei C, Ni C, Song T, Liu Y, Yang X, Zheng Z, Jia Y, Yuan Y, Guan K, Xu Y, Cheng X, Zhang Y, Yang X, Wang Y, Wen C, Wu Q, Shi W, Zhong H, The hepatitis B virus X protein disrupts innate immunity by downregulating mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein, J Immunol, 185 (2010) 1158–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hong-Taoa HE, Zhuob XU, Jiea LI, Prediction of mitochondrial haplotype M haplogroup for risk of HBV-hepatocellular carcinoma, Clinical Focus, (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bouchard MJ, Puro RJ, Wang L, Schneider RJ, Activation and inhibition of cellular calcium and tyrosine kinase signaling pathways identify targets of the HBx protein involved in hepatitis B virus replication, J Virol, 77 (2003) 7713–7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bouchard MJ, Wang LH, Schneider RJ, Calcium signaling by HBx protein in hepatitis B virus DNA replication, Science, 294 (2001) 2376–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williams GS, Boyman L, Chikando AC, Khairallah RJ, Lederer WJ, Mitochondrial calcium uptake, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 110 (2013) 10479–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hurst S, Hoek J, Sheu SS, Mitochondrial Ca 2+ and regulation of the permeability transition pore, J Bioenerg Biomembr, 49 (2017) 27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McClain SL, Clippinger AJ, Lizzano R, Bouchard MJ, Hepatitis B virus replication is associated with an HBx-dependent mitochondrion-regulated increase in cytosolic calcium levels, J Virol, 81 (2007) 12061–12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gearhart TL and Bouchard MJ, Replication of the hepatitis B virus requires a calcium-dependent HBx-induced G1 phase arrest of hepatocytes, Virology, 407 (2010) 14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Almas I, Afzal S, Ashraf MU, Zahid K, Rasheed A, Idrees M, Studies on circulating microRNAs: Members of Let-7 family and their correlation with Hepatitis C virus disease pathogenesis and treatment concerns, International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology IEEE, (2017) 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ploss A, Rice CM, Towards a small animal model for hepatitis C, Embo Reports, 10 (2009) 1220–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Elserag HB, Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med, 365 (2011) 1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Moradpour D, Penin F, Rice CM, Replication of hepatitis C virus, Nat Rev Microbiol, 5 (2007) 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ray RB, Meyer K, Ray R, Hepatitis C virus core protein promotes immortalization of primary human hepatocytes, Virology, 271 (2000) 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Arima N, Kao CY, Licht T, Padmanabhan R, Sasaguri Y, Padmanabhan R, Modulation of cell growth by the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS5A, J Biol Chem, 276 (2001) 12675–12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Suzuki R, Sakamoto S, Tsutsumi T, Rikimaru A, Tanaka K, Shimoike T, Moriishi K, Iwasaki T, Mizumoto K, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T, Suzuki T, Molecular determinants for subcellular localization of hepatitis C virus core protein, J Virol, 79 (2005) 1271–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Korenaga M, Otani K, Weinman SA, 481 HCV core protein inhibits mitochondrial complex I function and sensitizes mitochondria to oxidative damage, Hepatology, 38(2003) 392–392. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li Y, Boehning DF, Qian T, Popov VL, Weinman SA, Hepatitis C virus core protein increases mitochondrial ROS production by stimulation of Ca2+ uniporter activity, FASEB J, 21 (2007) 2474–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kim SJ, Syed GH, Siddiqui A, Hepatitis C virus induces the mitochondrial translocation of Parkin and subsequent mitophagy, PLOS Pathogens, 9 (2013) e1003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li XD, Sun L, Seth RB, Pineda G, Chen ZJ, Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 102 (2005) 17717–17722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhao P, Han T, Guo JJ, Zhu SL, Wang J, Ao F, Jing MZ, She YL, Wu ZH, Ye LB, HCV NS4B induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial death pathway, Virus Res, 169 (2012) 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hsieh MJ, Hong JU, Hsieh YS, Chen TY, Chiou HL, The Involvement of Mitochondrial-related Caspase Pathway in HCV NS5A-induced Apoptosis of Huh-7 Cells, J Bio Lab Sci, 22 (2010) 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pagliuca G, Martellucci S, Degener AM, Pierangeli A, Greco A, Fusconi M, Virgilio A.De., Gallipoli C, Vincentiis M.De., Gallo A, Role of Human Papillomavirus in the Pathogenesis of Laryngeal Dysplasia, Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 149 (2014) 1018–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N, Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical tumor worldwide, J Pathol, 189 (1999) 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jiang B, Xue M, Correlation of E6 and E7 levels in high-risk HPVl6 type cervical lesions with CCL20 and Langerhans cells, Genet Mol Res, 14 (2015) 10473–10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hildesheim A, Schiffman M, Bromley C, Wacholder S, Herrero R, Rodriguez A, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Scarpidis U, Lin QQ, Terai M, Bromley RL, Buetow K, Apple RJ, Burk RD, Human papilloma virus type 16 variants and risk of cervical cancer, J Natl Cancer Inst, 93 (2001) 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Freitas LB, Chen Z, Muqui EF, Boldrini NA, Miranda AE, Spano LC, Burk RD, Human papillomavirus 16 non-European variants are preferentially associated with high-grade cervical lesions, PLoS One, 9 (2014) e100746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Li N, Franceschi S, Howell-Jones R, Snijders PJ, Clifford GM, Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30848 invasive cervical tumors worldwide:Variation by geographical region,histological type and year of publication, Int J Cancer, 128 (2011) 927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zacapala-Gómez AE, Del Moral-Hernández O, Villegas-Sepúlveda N, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Romero-Córdoba SL, Beltrán-Anaya FO, Leyva-Vázquez MA, Alarcón-Romero Ldel C, Illades-Aguiar B, Changes in global gene expression profiles induced by HPV 16 E6 oncoprotein variants in cervical carcinoma C33-A cells, Virology, 488 (2016) 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Münger K, Basile JR, Duensing S, Eichten A, Gonzalez SL, Grace M, Zacny VL, Biological activities and molecular targets of the human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein, Oncogene, 20 (2001) 7888–7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Scheffner M, Werness BA, Huibregtse JM, Levine AJ, Howley PM, The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53, Cell, 63 (1990) 1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V, E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, Cancer Res, 56 (1996) 4620–4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Choo KB, Pan CC, Han SH, Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 into cellular DNA of cervical carcinoma: Preferential deletion of the E2 gene and invariable retention of the long control region and the E6/E7 open reading frames, Virology, 161 (1987) 259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gammoh N, Isaacson E, Tomaic´ V, Jackson DJ, Doorbar J, Banks L, Inhibition of HPV-16 E7 oncogenic activity by HPV-16 E2, Oncogene, 28 (2009) 2299–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Doorbar J, Ely S, Sterling J, McLean C, Crawford L, Specific interaction between HPV-16 E1-E4 and cytokeratins results in collapse of the epithelial cell intermediate filament network, Nature, 352 (1991) 824–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Parisi MA, Clayton DA, Similarity of human mitochondrial transcription factor 1 to high mobility group proteins, Science, 252 (1991) 965–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ngo HB, Kaiser JT, Chan DC, Tfam, a mitochondrial transcription and packaging factor, imposes a U-turn on mitochondrial DNA, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 18 (2011) 1290–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gao LJ, Gu PQ, Zhao W, Ding WY, Zhao XQ, Guo SY, Zhong TY, The role of globular heads of the C1q receptor in HPV 16 E2-induced human cervical squamous carcinoma cell apoptosis is associated with p38 MAPK/JNK activation, J Transl Med, 11 (2013) 347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yagi M, Uchiumi T, Takazaki S, Okuno B, Nomura M, Yoshida S, Kanki T, Kang D, p32/gC1qR is indispensable for fetal development and mitochondrial translation: importance of its RNA-binding ability, Nucleic Acids Res, 40 (2012) 9717–9737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lai D, Tan CL, Gunaratne J, Quek LS, Nei W, Thierry F, Bellanger S, Localization of HPV-18 E2 at Mitochondrial Membranes Induces ROS Release and Modulates Host Cell Metabolism, Plos One, 8 (2013) e75625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Guardado-Estrada M, Medina-Martínez I, Juárez-Torres E, Roman-Bassaure E, Macías L, Alfaro A, Alcántara-Vázquez A, Alonso P, Gomez G, Cruz-Talonia F, Serna L, Muñoz-Cortez S, Borges-Ibañez M, Espinosa A, Kofman S, Berumen J, The Amerindian mtDNA haplogroup B2 enhances the risk of HPV for cervical cancer: de-regulation of mitochondrial genes may be involved, J Hum Genet, 57 (2012) 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Raj K, Berguerand S, Southern S, Doorbar J, Beard P, E1Ê4 protein of human papillomavirus type 16 associates with mitochondria, J Virol, 78 (2004) 7199–7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mantovani F, Banks L, The human papillomavirus E6 protein and its contribution to malignant progression, Oncogene, 20 (2001) 7874–7887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA, HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, Science, 272 (1996) 872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].UNAIDS, WHO, 2007 AIDS epidemic update. http://allafrica.com/download/resource/main/main/idatcs/00011435:8968fa63f12ea2b3ce6a93e0f1d2a54c.pdf, 2007. (accessed 08.03.12).

- [63].Gilbert PB, McKeague IW, Eisen G, Mullins C, Guéye-NDiaye A, Mboup S, Kanki PJ, Comparison of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infectivity from a prospective cohort study in Senegal, Stat Med, 22 (2003) 573–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kuiken C, Foley B, Marx P, Wolinsky S, Leitner T, Hahn B, McCutchen F, Korber B, HIV Sequence Compendium 2008, first ed., Los Alamos, New Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA, Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody, Nature, 393 (1998) 648–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Berger G, Lawrence M, Hué S, Neil SJ, G2/M cell cycle arrest correlates with primate lentiviral Vpr interaction with the SLX4 complex, J Virol, 89 (2015) 230–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Ahmad N, Venkatesan S, Nef protein of HIV-1 is a transcriptional repressor of HIV-1 LTR, Science, 241 (1988) 1481–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Halestrap AP, Brenner C, The adenine nucleotide translocase: a central component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and key player in cell death, Curr Med Chem, 10 (2003) 1507–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Arunagiri C, Macreadie I, Hewish D, Azad A, A C-terminal domain of HIV-1 accessory protein Vpr is involved in penetration, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis of human CD4+ lymphocytes, Apoptosis, 2 (1997) 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Eura Y, Ishihara N, Oka T, Mihara K, Identification of a novel protein that regulates mitochondrial fusion by modulating mitofusin (Mfn) protein function, J Cell Sci, 119 (2006) 4913–4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Huang CY, Chiang SF, Lin TY, Chiou SH, Chow KC, HIV-1 Vpr Triggers Mitochondrial Destruction by Impairing Mfn2-Mediated ER-Mitochondria Interaction, PLoS One, 7 (2012) e33657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Espert L, Denizot M, Grimaldi M, Robert-Hebmann V, Gay B, Varbanov M, Codogno P, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Autophagy is involved in T cell death after binding of HIV-1 envelope proteins to CXCR4, J Clin Invest, 116 (2006) 2161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Roggero R, Robert-Hebmann V, Harrington S, Roland J, Vergne L, Jaleco S, Devaux C, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 to CXCR4 induces mitochondrial transmembrane depolarization and cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis independently of Fas signaling, J Virol, 75 (2001) 7637–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ladha JS, Tripathy MK, Mitra D, Mitochondrial complex I activity is impaired during HIV-1-induced T-cell apoptosis, Cell Death Differ, 12 (2005) 1417–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hendrickson SL, Hutcheson HB, Ruiz-Pesini E, Poole JC, Lautenberger J, Sezgin E, Kingsley L, Goedert JJ, Vlahov D, Donfield S, Wallace DC, O’Brien SJ, Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups influence AIDS Progression, Aids, 22 (2008) 2429–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Pyo CW, Yang YL, Yoo NK, Choi SY, Reactive oxygen species activate HIV long terminal repeat via post-translational control of NF-κB, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 376 (2008) 180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Tian C, Sun L, Jia B, Ma K, Curthoys N, Ding J, Zheng J, Mitochondrial Glutaminase Release Contributes to Glutamate-Mediated Neurotoxicity during Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection, J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 7 (2012) 619–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM, Virus Particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma, The Lancet, 1 (1964) 702–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Wang X, Kenyon WJ, Li Q, Müllberg J, Huttfletcher LM, Epstein-Barr virus uses different complexes of glycoproteins gH and gL to infect B lymphocytes and epithelial cells, J Virol, 72 (1998) 5552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Maeda E, Akahane M, Kiryu S, Kato N, Yoshikawa T, Hayashi N, Aoki S, Minami M, Uozaki H, Fukayama M, Ohtomo K, Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-related diseases: a pictorial review, Jpn J Radiol, 27 (2009) 4–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Old LJ, Boyse EA, Oettgen HF, De Harven E, Geering G, Williamson B, Clifford P, Precipitating antibody in human serum to an antigen present in cultured Burkitt’s lymphoma cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 56 (1966) 1699–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Raab-Traub N, Flynn K, Pearson G, Huang A, Levine P, Lanier A, Pagano J, The differentiated form of nasopharyngeal carcinoma contains Epstein-Barr virus DNA, Int J tumor, 39 (1987) 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Lo YM, Leung SF, Chan LY, Chan AT, Lo KW, Johnson PJ, Huang DP, Kinetics of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA during radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Cancer Res, 60 (2000) 2351–2355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Chan AT, Ma BB, Lo YM, Leung SF, Kwan WH, Hui EP, Mok TS, Kam M, Chan LS, Chiu SK, Yu KH, Cheung KY, Lai K, Lai M, Mo F, Yeo W, King A, Johnson PJ, Teo PM, Zee B, Phase II study of neoadjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel followed by radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: therapeutic monitoring with plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA, J Clin Oncol, 22 (2004) 3053–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Wang WY, Twu CW, Chen HH, Jan JS, Jiang RS, Chao JY, Liang KL, Chen KW, Wu CT, Lin JC, Plasma EBV DNA clearance rate as a novel prognostic marker for metastatic/recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Clin tumor Res, 16 (2010) 1016–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Le CC, Youlyouz-Marfak I, Adriaenssens E, Coll J,Bornkamm GW, Feuillard J, EBV latency III immortalization program sensitizes B cells to induction of CD95-mediated apoptosis via LMP-1: role of NF-kappaB, STAT1, and p53, Blood, 107 (2006) 2070–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Thornburg NJ, Kulwichit W, Edwards RH, Shair KH, Bendt KM, Raab-Traub N, LMP-1 signaling and activation of NF-kappaB in LMP-1 transgenic mice, Oncogene, 25 (2006) 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Deng L, Yang J, Zhao XR, Deng XY, Zeng L, Gu HH, Tang M, Cao Y, Cells in G2/M phase increased in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line by EBV-LMP-1 through activation of NF-kappaB and AP-1, Cell Res, 13 (2003) 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Uemura N, Kajino T, Sanjo H, Sato S, Akira S, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, TAK1 is a component of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 complex and is essential for activation of JNK but not of NF-kappaB, J Biol Chem, 281 (2006) 7863–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Fotheringham JA, Coalson NE, Raabtraub N, Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-2A induces ITAM/Syk- and Akt-dependent epithelial migration through αv-integrin membrane translocation, J Virol, 86 (2012) 10308–10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Chevallier-Greco A, Manet E, Chavrier P, Mosnier C, Daillie J, Sergeant A, Both Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded trans-acting factors, EB1 and EB2, are required to activate transcription from an EBV early promoter, EMBO J, 5 (1986) 3243–3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Cayrol C, Flemington EK, Identification of Cellular Target Genes of the Epstein-Barr Virus Transactivator Zta: Activation of Transforming Growth Factor bigh3 (TGF-bigh3) and TGF-b1, J Virol, 69 (1995) 4206–4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Yuling L, Jennifer WC, Tomlinson CC, Marielle Y, Shannon K, Fatty acid synthase expression is induced by the Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early protein BRLF1 and is required for lytic viral gene expression, J Virol, 78 (2004) 4197–4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Sarisky RT, Gao Z, Lieberman PM, Fixman ED, Hayward GS, Hayward SD, A replication function associated with the activation domain of the Epstein-Barr virus Zta transactivator, J Virol, 70 (1996) 8340–8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Miralles FJ, Shi Y, Wanrooij S, Zhu X, Jemt E, Persson O, Sabouri N, Gustafsson CM, Falkenberg M, In vivo occupancy of mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein supports the strand displacement mode of DNA replication, PLoS Genet, 10 (2014) e1004832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Wiedmer A, Wang P, Zhou J, Rennekamp AJ, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Lieberman PM, Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early protein Zta co-opts mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein to promote viral and inhibit mitochondrial DNA replication, J Virol, 82 (2008) 4647–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Xiong W, Zeng ZY, Xia JH, Xia K, Shen SR, Li XL, Hu DX, Tan C, Xiang JJ, Zhou J, Deng H, Fan SQ, Li WF, Wang R, Zhou M, Zhu SG, Lü HB, Qian J, Zhang BC, Wang JR, Ma J, Xiao BY, Huang H, Zhang QH, Zhou YH, Luo XM, Zhou HD, Yang YX, Dai HP, Feng GY, Pan Q, Wu LQ, He L, Li GY, A susceptibility locus at chromosome 3p21 linked to familial nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Cancer Res, 64 (2004) 1972–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Hu LF, Qiu QH, Fu SM, Sun D, Magnusson K, He B, Lindblom A, Ernberg I, A genome-wide scan suggests a susceptibility locus on 5p13 for nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Eur J Hum Genet, 16 (2008) 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Peng Z, Xie C, Wan Q, Zhang L, Li W, Wu S, Sequence variations of mitochondrial DNA D-loop region are associated with familial nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Mitochondrion, 11 (2011) 327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Chan AT, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Ann Oncol, Suppl 7 (2010) vii308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Hu SP, Du JP, Li DR, Yao YG, Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup Confers Genetic Susceptibility to Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in Chaoshanese from Guangdong, China, PLoS One, 9 (2014) e87795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Lee S, Wi SM, Min Y, Lee KY, Peroxiredoxin-3 Is Involved in Bactericidal Activity through the Regulation of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species, Immune Netw, 16 (2016) 373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Liu J, Zhan X, Li M, Li G, Zhang P, Xiao Z, Shao M, Peng F, Hu R, Chen Z, Mitochondrial proteomics of nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis, BMC Med Genomics, 5 (2012) 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Pal A, Basak NP, Banerjee AS, Banerjee S, Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-2A alters mitochondrial dynamics promoting cellular migration mediated by Notch signaling pathway, Carcinogenesis, 35 (2014) 1592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Dalal S, Zha Q, Daniels CR, Steagall RJ, Joyner WL, Gadeau AP, Singh M, Singh K, Osteopontin stimulates apoptosis in adult cardiac myocytes via the involvement of CD44 receptors, mitochondrial death pathway, and endoplasmic reticulum stress, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 306 (2014) H1182–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Ashida H, Mimuro H, Ogawa M, Kobayashi T, Sanada T, Kim M, Sasakawa C, Host–pathogen interactions: Cell death and infection: A double-edged sword for host and pathogen survival, J Cell Biol, 195 (2011) 931–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ohta A, Nishiyama Y, Mitochondria and viruses, Mitochondrion, 11 (2011) 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].D’Agostino DM, Silic-Benussi M, Hiraragi H, Lairmore MD, Ciminale V, The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 p13II protein: effects on mitochondrial function and cell growth, Cell Death Differ, 12 (2005) 905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Wasilenko ST, Stewart TL, Meyers AF, Barry M, Vaccinia virus encodes a previously uncharacterized mitochondrial-associated inhibitor of apoptosis, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 100 (2003) 14345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Zhai D, Yu E, Jin C, Welsh K, Shiau CW, Chen L, Salvesen GS, Liddington R, Reed JC, Vaccinia virus protein F1L is a caspase-9 inhibitor, J Biol Chem, 285 (2010) 5569–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Arnoult D, Bartle LM, Skaletskaya A, Poncet D, Zamzami N, Park PU, Sharpe J, Youle RJ, Goldmacher VS, Cytomegalovirus cell death suppressor vMIA blocks Bax- but not Bak-mediated apoptosis by binding and sequestering Bax at mitochondria, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 101 (2004) 7988–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Corcoran JA, Saffran HA, Duguay BA, Smiley JR, Herpes Simplex Virus UL12.5 Targets Mitochondria through a Mitochondrial Localization Sequence Proximal to the N Terminus, J Virol, 83 (2009) 2601–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]