Abstract

Background

This study was designed to investigate the impact of anti-tumor approaches (including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, endocrine therapy, immunotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy) on the outcomes of cancer patients with COVID-19.

Methods

Electronic databases were searched to identify relevant trials. The primary endpoints were severe disease and death of cancer patients treated with anti-tumor therapy before COVID-19 diagnosis. In addition, stratified analyses were implemented towards various types of anti-tumor therapy and other prognostic factors. Furthermore, odds ratios (ORs) were hereby adopted to measure the outcomes with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

As indicated in the study consisting of 9231 individuals from 52 cohorts in total, anti-tumor therapy before COVID-19 diagnosis could elevate the risk of death in cancer patients (OR: 1.21, 95%CI: 1.07–1.36, P = 0.0026) and the incidence of severe COVID-19 (OR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.01–1.40, P = 0.0412). Among various anti-tumor approaches, chemotherapy distinguished to increase the incidence of death (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.08–1.38, P = 0.0013) and severe COVID-19 (OR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.02–1.18, P = 0.0165) as to cancer patients with COVID-19. Moreover, for cancer patients with COVID-19, surgery and targeted therapy could add to the risk of death (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.00–1.61, P = 0.0472), and the incidence of severe COVID-19 (OR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.01–1.30, P = 0.0357) respectively. In the subgroup analysis, the incidence of death (OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.03–1.34, P = 0.0158) raised in case of chemotherapy adopted for solid tumor with COVID-19. Besides, age, gender, hypertension, COPD, smoking and lung cancer all served as potential prognostic factors for both death and severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19.

Conclusions

Anti-tumor therapy, especially chemotherapy, augmented the risk of severe disease and death for cancer patients with COVID-19, so did surgery for the risk of death and targeted therapy for the incidence of severe COVID-19.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-022-09320-x.

Keywords: Anti-tumor therapy, cancer, COVID-19, Chemotherapy, Solid tumor

Background

As is known to all, the sudden outbreak and global overrun of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1], have generated heavy burdens and great challenges to global public health since December 2019 [2]. Up to date, people all over the world have been fighting against the fatal disease, as reported in over 200 million infected individuals.

Cancer patients are generally in severe immunosuppressive status deriving from cancer itself and the anti-tumor regimens. Furthermore, they have to visit the hospital regularly for monitoring or anti-tumor treatment (such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, surgery and radiotherapy) leading to increasing exposure to virus.

A growing number of studies revealed that, during the pandemic, cancer patients with COVID-19 generally suffered from worse outcomes compared to patients with COVID-19 alone [3–7]. In addition, some investigations targeted at exploring whether anti-tumor therapy was an additional risk factor for adverse outcomes of COVID-19 and whether it was necessary to change therapeutic modalities to mitigate the risk [8–10].

As far as we know, accumulating prospective and retrospective studies were conducted to evaluate clinical characteristics of cancer patients with COVID-19, as well as the impact of anti-tumor therapy on clinical outcomes of COVID-19 [11–13]. Nevertheless, research findings remained to be a bit conflicting and inconclusive as for the impact of anti-tumor therapeutic approaches on the severity of COVID-19 [14–18]. Consequently, a comprehensive survey based on a larger scale (52 cohorts incorporating 9231 individuals) and diverse dimensions was hereby carried out to clarify the correlation between anti-tumor therapy and COVID-19 prognosis.

Methods

Data sources and literature searches

A systematic electronic literature retrieval was in place for study screening, searching for abstracts of relevant studies in the published literature. PubMed, Cochrane Library and EMBASE were all searched with data updated as of 27th March 2021. Basic search terms entered were as follows: “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV2”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “2019-nCoV”, “novel coronavirus”, “cancer”, “neoplasm”, “malignancy”, “carcinoma” and “tumor” (the full search strategy as shown in Additional file 1: Appendix 1). In addition, full-text papers were scrutinized as for abstracts without substantial information, and the references of relevant articles were reviewed for additional studies. Data retrieval was completed in English, with reviews, editorials comments and case reports all excluded.

Selection of studies and definition

Initially, two investigators performed a screening of titles and abstracts respectively, then examined the full-text of articles to acquire eligible studies. Regarding the duplicate studies based on the same patients, only the latest or most comprehensive data were recruited as a whole.

Definition:

Anti-tumor therapy: patients receiving chemotherapy (cytotoxic chemotherapy), immunotherapy (immune checkpoint inhibitor), targeted therapy (molecular targeted therapy), surgery, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy (hormonal drugs) within the last 6 months before COVID-19 diagnosis.

Age: defined as “old” or “young” depending on each cut-off used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) of age in the included studies.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale (ECOG PS): defined as “high” or “low” with a cut-off of 2.

Comorbidities: defined as “yes” or “no” to identify cancer patients with or without hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease, obesity status and smoking in the corresponding studies.

Blood parameters: defined as “high” or “normal” on the basis of each cut-off applied to calculate the ORs of white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP), lymphocyte count, D-dimer, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and creatine kinase in each included study.

Severe COVID-19: depending on respective definitions in the included studies, including infections requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation or even resulting in death.

Inclusion criteria

1) Prospective or retrospective studies to evaluate the impact of anti-tumor therapy on cancer patients with COVID-19; 2) patients pathologically confirmed as cancer; 3) patients diagnosed as COVID-19; 4) studies with data available for ORs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of severe COVID-19 and death rates in groups receiving anti-tumor treatments or not.

Data extraction

In this study, data extraction was implemented strictly according to the PRISMA guidelines (as shown in Additional file 2: Appendix 2). Meanwhile, all eligible studies involved the information as follows: the publication year and region, first author’s name, study type, number of patients, anti-tumor therapy, severe COVID-19 and/or death cases.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed independently by two reviewers using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case-control and cohort studies, encompassing three dimensions of selection, comparability and exposure, with a full score of 9 points.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoints were composed of death and/or severe COVID-19 of cancer patients treated with anti-tumor therapy before COVID-19 diagnosis. Moreover, the correlation between anti-tumor therapy and the outcomes was determined by ORs with the corresponding 95%CIs. Subgroup analyses were further accomplished based on the type of anti-tumor therapy, type of cancer (solid cancer or haematological malignancy) and other prognostic factors. In addition, funnel plots and Egger’s test were applied to evaluate publication bias, and statistical analysis was realized via R 4.0 statistical software. Heterogeneity was assessed by means of I-square tests and chi-square, with remarkable heterogeneity in case of P < 0.1 or I2 > 40%. Furthermore, a random effect model was adopted to analyze the pooled data when heterogeneity existed; otherwise, a fixed effect model was employed accordingly.

Results

Selection of study

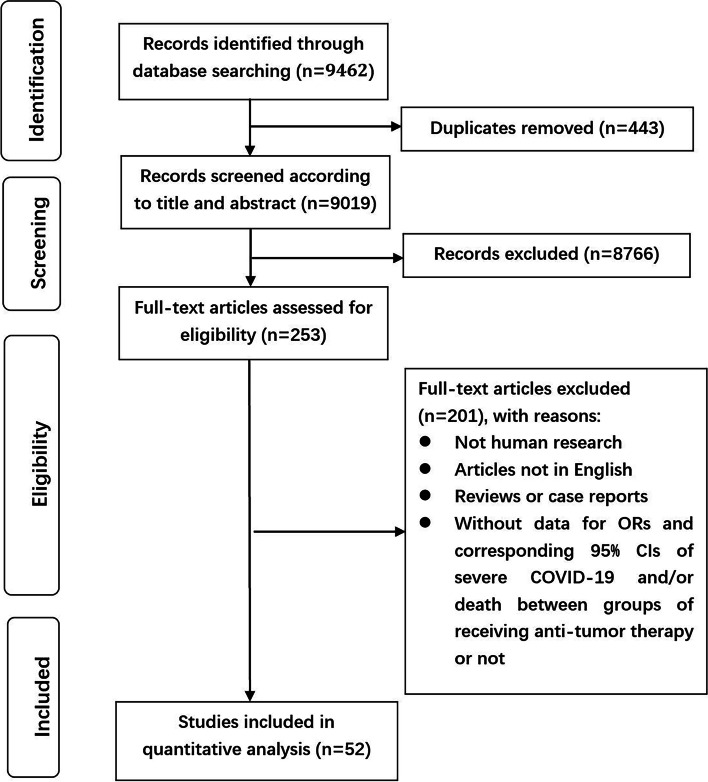

Initially, 9462 relevant articles were scrutinized intensively, of which 443 were filtered for duplication, and 8766 were excluded for digression after screening the titles and abstracts. After that, the full text of remaining 253 articles was thoroughly reviewed, among which 201 were excluded as they were reviews or case reports, not human research, not in English, without data for ORs and corresponding 95%CIs of severe COVID-19 and/or death in groups receiving anti-tumor therapy or not. Finally, a total of 52 cohorts [4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 14–60] incorporating 9231 participants were recruited in this study. See Fig. 1 for detailed procedures.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart on selection including trials in the meta-analysis

Study traits

As of 27th March 2021, altogether 9231 individuals in 52 cohorts were included with a sample size ranging from 12 to 1289, of which 45 were retrospective, 4 prospective and 3 retro-prospective. Meanwhile, ORs for severe COVID-19 and/or death were utilized to assess the impact of anti-tumor approaches on cancer patients with COVID-19. Among the foregoing studies, 41 cohorts witnessed death and 23 confronted with severe COVID-19. See Table 1 for principal characteristics.

Table 1.

The principal characteristics and further details of eligible articles

| Author | Year | Study design | Region | Number of patient | Male | Median age (IQR) (years) | Diagnosis method for COVID-19 | Cancer type | Comparison group | |||

| Kuderer NM [6] | 2020 | Retro-prospective | multi-national | 928 | 468 | 66 (57–76) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Lee LYW [19] | 2020 | Prospective | UK | 800 | 449 | 69 (59–76) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Zhang L [14] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 28 | 17 | 65 (56–70) | RT-PCR | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Stroppa EM [20] | 2020 | Retrospective | Italy | 25 | 20 | 71 (mean) (50–84) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Yang K [7] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 205 | 96 | 63 (56–70) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Zhang H [21] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 107 | 60 | 66 (36–98) | RT-PCR and/or radiology | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Robilotti EV [22] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 423 | 212 | NA | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Yarza R [23] | 2020 | Prospective | Spain | 63 | 34 | NA | RT-PCR and/or radiology | solid tumor | cancer patients treated other options | |||

| Li Q [24] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 59 | 31 | 63 (54–70) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Jee J [25] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 309 | 159 | NA | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Sanchez-Pina JM [26] | 2020 | Retrospective | Spain | 39 | 23 | 64 (mean) | RT-PCR | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Pinato DJ [15] | 2020 | Retrospective | multi-national | 890 | 503 | 68 (mean) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Assaad S [27] | 2020 | Retrospective | France | 55 | 26 | 64 (mean) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Garassino MC [28] | 2020 | Retrospective | multi-national | 200 | 141 | 68 (61–75) | RT-PCR | Thoracic Cancer | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Liang WH [29] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 18 | 12 | 60 (47–87) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Ma J [30] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 37 | 20 | 62 (IQR: 59–70) | RT-PCR and/or antibody test | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Mehta V [11] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 218 | 127 | 69 (10–92) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Yu J [31] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 12 | 10 | 66 (48–78) | RT-PCR and/or CT | solid tumor | cancer patients with no active antitumor treatment | |||

| Tian J [4] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 232 | 119 | 64 (58–69) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with surgery | |||

| Fox TA [32] | 2020 | Retrospective | UK | 55 | 38 | 63 (23–88) | RT-PCR, CT, and clinical features | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Booth S [33] | 2020 | Prospective | UK | 66 | 41 | 73 (IQR: 63–81) | RT-PCR, radiological, and clinical features | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Cattaneo C [34] | 2020 | Retrospective | Italy | 102 | 66 | 68 (mean) | RT-PCR | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Lara OD [35] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 121 | NA | 64 (IQR: 51–73) | RT-PCR and CT | gynecologic cancer | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Liu C [36] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 216 | 113 | 63 (IQR: 57–70) | RT-PCR | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Luo J [37] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 102 | 49 | 68 (IQR: 61–75) | RT-PCR | lung cancer | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Mato AR [38] | 2020 | Retrospective | multi-national | 198 | 125 | 63 (35–92) | RT-PCR | chronic lymphocytic leukemia | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Rogado J [39] | 2020 | Retrospective | Spain | 45 | 30 | 71 (34–90) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Russell B [40] | 2020 | Retro-prospective | UK | 156 | 90 | 65 (mean) | RT-PCR | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Scarfò L [41] | 2020 | Retrospective | multi-national | 190 | 126 | 72 (48–94) | RT-PCR | chronic lymphocytic leukemia | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Vuagnat P [42] | 2020 | Retrospective | France | 58 | NA | 58 (IQR:48–68) | RT-PCR and/or CT | breast cancer | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Wang BO [43] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 58 | 30 | 67 | RT-PCR | multiple myeloma | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Wang J [44] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 283 | 141 | 63 (IQR: 55–70) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Gonzalez-cao M [45] | 2020 | Retrospective | Spain | 50 | 27 | 69 (6–94) | clinical or RT-PCR | melanoma | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| De Melo AC [46] | 2020 | Retrospective | Brazil | 181 | 71 | 55 (2–88) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no active antitumor treatment | |||

| Albiges L [47] | 2020 | Retrospective | France | 178 | 76 | 61 (52–71) | RT-PCR and/or CT | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Martínez-López J [48] | 2020 | Retrospective | Spain | 167 | 95 | 71 (IQR: 62–78) | RT-PCR | multiple myeloma (MM) | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Martín-Moro F [49] | 2020 | Retrospective | Spain | 34 | 19 | 72.5 (35–94) | RT-PCR and/or CT | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Lattenist R [50] | 2021 | Retrospective | Belgium | 13 | 10 | 70 (IQR: 59–79) | RT-PCR and/or CT | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Nakamura S [51] | 2020 | Retrospective | Japan | 32 | 22 | 74.5 (24–90) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Rogiers A [52] | 2021 | Retrospective | multi-national | 110 | 72 | 63 (27–86) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Glenthøj A [16] | 2021 | Prospective | Denmark | 66 | 40 | 66.7 (25–91) | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | ||||

| Song C [17] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 223 | 116 | 63 (56–71) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with discontinous treatment | |||

| Lunski MJ [18] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 312 | 142 | NA | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Nie L [53] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 45 | 31 | 66 (58–74) | RT-PCR | lung cancer | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Larfors G [54] | 2020 | Retrospective | Sweden | NA | NA | NA | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| H€ollein A [55] | 2020 | Retrospective | Germany | 17 | 8 | 73 (27–82) | RT-PCR | non-specific | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Garnett C [56] | 2020 | Retrospective | UK | 32 | 21 | 72.5 (46–96) | RT-PCR | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Hanna GJ [57] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 32 | 20 | 70 (38–91) | RT-PCR | head and neck cancer | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Lie’vre A [58] | 2020 | Retro-prospective | France | 1289 | 795 | 67 (19–100) | RT-PCR | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Smith M [59] | 2020 | Retrospective | USA | 86 | NA | 69 (mean) | RT-PCR | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Wu YG [60] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 14 | 9 | 37 (14–68) | RT-PCR | hematological malignancies | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Yang F [12] | 2020 | Retrospective | China | 52 | 28 | 63 (34–98) | RT-PCR | solid tumor | cancer patients with no treatment | |||

| Author | Number of the control | Anti-tumor therapy | Chemotherapy | Immunotherapy | Targeted therapy | Endocrine therapy | Surgery | Radiotherapy | Outcome | Required mechanical ventilation | Severe COVID-19 | Death |

| Kuderer NM [6] | 553 | 366 | 160 | 38 | 75 | 85 | 32 | 12 | death | 116 | 242 | 121 |

| Lee LYW [19] | 272 | 528 | 281 | 44 | 72 | 64 | 29 | 76 | death | NA | 360 | 226 |

| Zhang L [14] | 22 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 1 | sever COVID-19 | 10 | 15 | 8 |

| Stroppa EM [20] | 13 | 12 | 8 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 9 |

| Yang K [7] | 128 | 54 | 31 | 4 | 12 | NA | 4 | 9 | death | 32 | 52 | 40 |

| Zhang H [21] | 70 | 37 | NA | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | 56 | 23 |

| Robilotti EV [22] | NA | NA | 191 | 31 | NA | NA | 31 | NA | sever COVID-19 | 40 | 85 | 51 |

| Yarza R [23] | NA | NA | 36 | 8 | 7 | 10 | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 24 | 16 |

| Li Q [24] | 43 | 16 | 12 | NA | 6 | NA | 1 | 1 | death | 27 | 35 | 16 |

| Jee J [25] | 43 | 170 | 102 | 18 | 49 | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 120 | 31 |

| Sanchez-Pina JM [26] | 15 | 24 | 4 | NA | 5 | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | 18 | NA |

| Pinato DJ [15] | 403 | 479 | 206 | 56 | 93 | 92 | NA | 33 | sever COVID-19; death | 97 | 565 | 299 |

| Assaad S [27] | 26 | 29 | 16 | 3 | 14 | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 30 |

| Garassino MC [28] | 58 | 142 | 48 | 34 | 28 | NA | NA | NA | death | 9 | NA | 66 |

| Liang WH [29] | 14 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 9 | NA |

| Ma J [30] | 24 | 13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 20 | 5 |

| Mehta V [11] | NA | NA | 42 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | 49 | death | 45 | NA | 61 |

| Yu J [31] | 5 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 1 | NA | 1 | 4 | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 3 | 3 |

| Tian J [4] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 119 | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 148 | NA |

| Fox TA [32] | NA | NA | 29 | 25 | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 25 | 19 |

| Booth S [33] | 29 | 37 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 34 |

| Cattaneo C [34] | 43 | 59 | 20 | 28 | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 40 |

| Lara OD [35] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | 20 | NA |

| Liu C [36] | 138 | 78 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 37 |

| Luo J [37] | 48 | 54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | 18 | NA | 25 |

| Mato AR [38] | 79 | 119 | 51 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | 53 | NA | 66 |

| Rogado J [39] | 15 | 30 | 19 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | 29 | 19 |

| Russell B [40] | 18 | 81 | 45 | 7 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 28 | 34 |

| Scarfò L [41] | 73 | 116 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 151 | 56 |

| Vuagnat P [42] | NA | NA | 29 | NA | 19 | 19 | 3 | 36 | sever COVID-19 | NA | NA | 4 |

| Wang BO [43] | 11 | 47 | NA | NA | 28 | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 14 |

| Wang J [44] | 188 | 95 | 46 | NA | 12 | NA | 23 | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | NA | 50 |

| Gonzalez-cao M [45] | 12 | 38 | NA | 22 | 16 | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 34 | 13 |

| De Melo AC [46] | 16 | 165 | 63 | NA | NA | 20 | 12 | 10 | death | 34 | NA | 60 |

| Albiges L [47] | 61 | 117 | 66 | 19 | 30 | 16 | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 47 | 31 |

| Martínez-López J [48] | NA | NA | 83 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | 15 | 141 | 56 |

| Martín-Moro F [49] | NA | 19 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | 4 | 17 | 11 |

| Lattenist R [50] | 6 | 7 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 6 |

| Nakamura S [51] | 19 | 13 | 10 | 3 | NA | 4 | 13 | NA | death | 3 | NA | 11 |

| Rogiers A [52] | NA | NA | 25 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | 35 | 18 |

| Glenthøj A [16] | 10 | 9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 33 | NA |

| Song C [17] | 19 | 204 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 159 | NA |

| Lunski MJ [18] | 256 | 56 | 12 | 4 | 9 | 44 | 5 | 2 | death | NA | NA | 66 |

| Nie L [53] | 34 | 11 | 4 | 4 | NA | NA | 3 | NA | death | 3 | 23 | 11 |

| Larfors G [54] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19; death | NA | NA | NA |

| H€ollein A [55] | 2 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 1 | death | 3 | NA | 6 |

| Garnett C [56] | 10 | 22 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 18 |

| Hanna GJ [57] | 26 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | NA | 4 | 1 | death | NA | NA | NA |

| Lie’vre A [58] | NA | NA | 577 | 110 | 181 | 57 | 56 | 133 | death | 49 | NA | 370 |

| Smith M [59] | 47 | 39 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 29 | NA |

| Wu YG [60] | NA | NA | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | death | NA | NA | 6 |

| Yang F [12] | NA | NA | 6 | 1 | NA | NA | 2 | NA | sever COVID-19 | NA | 19 | 11 |

Abbreviations: ICIs Immune checkpoint inhibitors, RT-PCR Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, NA Not available, ICU Intensive Care Unit

Assessment of study quality and publication bias

Refer to Additional file 3: Appendix 3 for quality assessment of 52 recruited studies. Furthermore, no publication bias was defined via Egger’s tests in the pooled analyses for various anti-tumor approaches (see Additional file 4: Appendix 4) and supernumerary prognostic factors (see Additional file 5: Appendix 5).

Data analysis

In this study, regarding cancer patients treated with anti-tumor therapy before COVID-19 diagnosis, the pooled OR was 1.21 (95%CI: 1.07–1.36, P = 0.0026) (Fig. 2A) for death without publication bias (Fig. 2C, Egger’s test: P = 0.5516), and 1.19 (95%CI: 1.01–1.40, P = 0.0412) (Fig. 2B) for severe COVID-19 without publication bias (Fig. 2D, Egger’s test: P = 0.3930).

Fig. 2.

The impact of anti-tumor therapy on clinical outcomes of cancer patients with COVID-19. Forest plots of (A) death, B severe COVID-19 between groups divided by receiving anti-tumor therapy or not before COVID-19 diagnosis; Funnel plots of (C) death, D severe COVID-19 between groups divided by receiving anti-tumor therapy or not before COVID-19 diagnosis

The impact of anti-tumor therapy on death and severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19

As for cancer patients with COVID-19, compared with patients without anti-tumor approaches, the incidence of death appeared to be higher in patients treated with chemotherapy (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.08–1.38, P = 0.0013) (Fig. 3A) and surgery (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.00–1.61, P = 0.0472) (Fig. 3B), but not in patients receiving radiotherapy (OR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.75–1.09, P = 0.2817), targeted therapy (OR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.76–1.23, P = 0.7914), endocrine therapy (OR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.80–1.12, P = 0.5097), and immunotherapy (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 0.90–1.22, P = 0.5412) (Additional file 6: Appendix 6).

Fig. 3.

The impact of various anti-tumor approaches on clinical outcomes of cancer patients with COVID-19. The impact of (A) chemotherapy and (B) surgery on death of cancer patients with COVID-19; The impact of (C) chemotherapy and (D) targeted therapy on severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19

Compared with cancer patients without anti-tumor approaches, the incidence of severe COVID-19 was higher in patients receiving chemotherapy (OR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.02–1.18, P = 0.0165) (Fig. 3C) and targeted therapy (OR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.01–1.30, P = 0.0357) (Fig. 3D), but not in patients treated with surgery (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 0.89–1.47, P = 0.2888) and immunotherapy (OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 0.97–1.45, P = 0.1034) (Additional file 6: Appendix 6).

Subgroup analysis

Patients were further divided into groups of solid tumor and haematological malignancy depending on the type of cancer, as listed in Table 2. Compared with patients without anti-tumor approaches, solid tumor patients with COVID-19 witnessed higher incidence of death after receiving chemotherapy (OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.03–1.34, P = 0.0158), but not the case in haematological malignancy patients with COVID-19 (OR = 1.41, 95%CI: 0.74–2.68, P = 0.2964).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the impact of anti-tumor therapy on death and severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19

| Anti-tumor therapy | Solid tumour | Haematological malignancy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| death | severe COVID-19 | death | severe COVID-19 | |||||

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Chemotherapy | 1.17 (1.03–1.34) | 0.0158 | 1.16 (0.81–1.66) | 0.4072 | 1.41 (0.74–2.68) | 0.2964 | NA | NA |

| Radiotherapy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Targeted therapy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Surgery | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Endocrine therapy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Immunotherapy | 0.91 (0.47–1.76) | 0.7705 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Antitumor therapy | 1.15 (0.94–1.42) | 0.1815 | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) | 0.4643 | 1.26 (0.91–1.75) | 0.1597 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations NA Not available, OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval

Supernumerary prognostic factors for death and severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19

The potential prognostic factors for the death of cancer patients with COVID-19 were as follows: age (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.12–1.19, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A), gender (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.11–1.34, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4B), hypertension (OR = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.22–1.41, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4C), diabetes (OR = 1.31, 95%CI: 1.20–1.42, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4D), COPD (OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.08–1.41, P = 0.0016) (Fig. 4E), cardiovascular disease (OR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.15–1.55, P = 0.0001) (Fig. 4F), smoking (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.14–1.47, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4G), ECOG PS (OR = 1.73, 95%CI: 1.47–2.03, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4H), lung cancer (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.05–1.81, P = 0.0200) (Fig. 4I), white blood cell count (OR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.17–2.97, P = 0.0093) (Fig. 4J), and CRP (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.00–1.05, P = 0.0298) (Fig. 4K). Nevertheless, obesity status (OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.91–1.15, P = 0.6827), lymphocyte count (OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 0.57–2.68, P = 0.5868), D-dimer (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.98–1.05, P = 0.3981) and NLR (OR = 1.30, 95%CI: 0.64–2.64, P = 0.4763) were not highly correlated to the death of cancer patients with COVID-19 (Additional file 7: Appendix 7).

Fig. 4.

The supernumerary prognostic factors for death of cancer patients with COVID-19. A Age (old vs. young); B Gender (male vs. female); C Hypertension (yes vs. no); D Diabetes (yes vs. no); E Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (yes vs. no); F Cardiovascular disease (yes vs. no); G Smoking (yes vs. no); H Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale (ECOG PS) (high vs. low); I Type of solid tumor (lung cancer vs. other solid tumor); J White blood cell count (high vs. normal); K C-reactive protein (high vs. normal)

Furthermore, the potential prognostic factors for severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19 included age (OR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.05–1.15, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5A), gender (OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.04–1.21, P = 0.0017) (Fig. 5B), hypertension (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.02–1.45, P = 0.0286) (Fig. 5C), COPD (OR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.01–1.43, P = 0.0416) (Fig. 5D), smoking (OR = 1.21, 95%CI: 1.08–1.35, P = 0.0008) (Fig. 5E), and lung cancer (OR = 1.30, 95%CI: 1.08–1.56, P = 0.0055) (Fig. 5F). However, such factors as diabetes (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.88–1.20, P = 0.7415), obesity status (OR = 1.00, 95%CI: 0.92–1.10, P = 0.9254), ECOG PS (OR = 1.39, 95%CI: 0.93–2.07, P = 0.1119), white blood cell count (OR = 1.90, 95%CI: 0.88–4.11, P = 0.1026), CRP (OR = 1.39, 95%CI: 0.77–2.50, P = 0.2735), lymphocyte count (OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.76–1.36, P = 0.9093), D-dimer (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 0.98–1.13, P = 0.1387), and creatine kinase (OR = 1.52, 95%CI: 0.83–2.77, P = 0.1762) did not obviously influence the severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19 (Additional file 7: Appendix 7).

Fig. 5.

The supernumerary prognostic factors for severe disease of cancer patients with COVID-19. A Age (old vs. young); B Gender (male vs. female); C Hypertension (yes vs. no); D COPD (yes vs. no); E Smoking (yes vs. no); F Type of solid tumor (lung cancer vs. other solid tumor)

Subgroup analysis

Depending on the type of cancer, patients were further assigned into groups of solid tumor and haematological malignancy, as listed in Additional file 8: Appendix 8.

The potential prognostic factors for the death of solid tumor patients with COVID-19 included age (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.00–1.01, P = 0.0168), gender (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 1.09–1.36, P = 0.0006), hypertension (OR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.00–1.42, P = 0.0446), and smoking (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.04–1.35, P = 0.0110).

Furthermore, age (OR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.20–1.57, P < 0.0001), hypertension (OR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.02–1.41, P = 0.0246) and diabetes (OR = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.03–1.53, P = 0.0245) ranked as the potential prognostic factors for the death of haematological malignancy patients with COVID-19.

Discussion

A meta-analysis involving 15 studies demonstrated that chemotherapy could increase the risk of death from COVID-19 in cancer patients [61]. To our best knowledge, this study composed of 52 cohorts involving 9231 cancer patients with COVID-19, was so far the largest-scale investigation with respect to the impact of anti-tumor approaches on clinical outcomes of cancer patients with COVID-19, indicating that cancer patients with recent anti-tumor therapy (especially chemotherapy) were generally susceptible to develop into severe COVID-19, or even death.

Firstly, cancer patients with COVID-19 receiving chemotherapy were more likely to confront with severe disease and death, probably because patients treated with chemotherapy were susceptible to suffer from bone marrow suppression (including severe neutropenia or lymphocytopenia) and impaired immunity [62, 63], even respiratory infections (involving viral etiology) [64]. Furthermore, the recovery of immune system might take a long time after the weakening of immune functions by chemotherapy [65]. As a result, cancer patients with COVID-19 failed to effectively activate the immune system to eliminate the virus in a timely manner [66], that’s why they were more likely to trigger severe disease or even death.

Secondly, recent surgery might lead to increasing risk of death and a trend of severe disease in cancer patients with COVID-19, partially attributable to their frequent visits to hospital and postoperative negative nitrogen balance. Moreover, the stress and trauma caused by surgery could be clinically manifested as decreased immunity, since numerous studies revealed that the immunity of patients would reduce to a certain extent in a period of time after surgery [67].

Thirdly, patients administered with targeted therapy before COVID-19 diagnosis faced with elevated risk of severe disease. Despite targeted therapy seldomly impaired the immunity system of cancer patients, all those receiving maintenance targeted therapy suffered from advanced disease and many complications in general, giving rise to clinical worsening as a result.

Finally, tumor immunotherapy has played an increasingly crucial role in the field of anti-tumor treatment over the past decade [68]. As shown in our study, cancer patients with COVID-19 who received immunotherapy recently did not generate a higher rate of severe disease or death when comparing to those without immunotherapy.

In summary, this study aimed at providing clinicians with preliminary evidence for the safety of anti-tumor approaches during COVID-19. As to patients with COVID-19 who received anti-tumor approaches recently, especially chemotherapy, surgery and targeted therapy, clinicians should focus on disease progression and make intervention in a timely manner when necessary. Furthermore, intensive nursing and positive measures shall be taken to improve the prognosis and reduce the risk of death in practice.

Limitations

This study came up with four drawbacks as follows: firstly, limited studies related to radiotherapy, surgery and endocrine therapy might affect the accuracy of pooled results to some degree; secondly, 23 included studies failed to separate solid tumor from haematological malignancy for investigating the impact of anti-tumor approaches on the clinical outcomes, which might influence the accuracy of results; thirdly, bias might exist to some extent for excluding relevant studies published in non-English language; lastly, other forms of bias should be taken into account as follows: position bias (e.g. different health care systems and national policies in managing COVID-19) and time lag bias (time of study: start of pandemic vs. later phase of pandemic), which were not available in the included studies.

Conclusions

Anti-tumor therapy, especially chemotherapy, augmented the risk of severe disease and death for cancer patients with COVID-19, so did surgery for the risk of death and targeted therapy for the incidence of severe COVID-19.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

None.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Registration and protocol

The review was not registered and the protocol was not prepared.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ORs

Odds ratios

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale

- NLR

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- T-PCR

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- NA

Not available

- ICU

Intensive care unit

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Qing Wu, Shuimei Luo and Xianhe Xie. The first draft of manuscript was written by Qing Wu, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atzrodt CL, Maknojia I, McCarthy RDP, et al. A guide to COVID-19: a global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. FEBS J. 2020;287(17):3633–3650. doi: 10.1111/febs.15375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Siempos II. Effect of cancer on clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of patient data. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6(6):799–808. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian J, Yuan X, Xiao J, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 disease severity in patients with CANCER in Wuhan, China: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):893–903. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(6):783–791. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. COVID-19 and Cancer consortium. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with Cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang K, Sheng Y, Huang C, et al. Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and risk factors for mortality in patients with Cancer and COVID-19 in Hubei, China: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):904–913. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30310-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, et al. International research network on COVID-19 impact on cancer care. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: a global collaborative study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1428–1438. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balogun OD, Bea VJ, Phillips E. Disparities in cancer outcomes due to COVID-19 – a tale of 2 cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(10):1531. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pathania AS, Prathipati P, Abdul BA, et al. COVID-19 and Cancer comorbidity: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Theranostics. 2021;11(2):731–753. doi: 10.7150/thno.51471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):935–941. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang F, Shi S, Zhu J, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Cancer patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2067–2073. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected Cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinato DJ, Zambelli A, Aguilar-Company J, et al. Clinical portrait of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in European cancer patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(10):1465–1474. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glenthøj A, Jakobsen LH, Sengeløv H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients with Haematological disorders: severity and one-month outcome in 66 Danish patients in a Nationwide cohort study. Eur J Haematol. 2021;106(1):72–81. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song C, Dong Z, Gong H, et al. An online tool for predicting the prognosis of Cancer patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multi-center study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147(4):1247–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunski MJ, Burton J, Tawagi K, et al. Multivariate mortality analyses in COVID-19: comparing patients with Cancer and patients without Cancer in Louisiana. Cancer. 2021;127(2):266–274. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee LY, Cazier JB, Angelis V, et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with Cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1919–1926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroppa EM, Toscani I, Citterio C, et al. Coronavirus Disease-2019 in Cancer patients. A report of the first 25 Cancer patients in a Western country (Italy) Future Oncol. 2020;16(20):1425–1432. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Wang L, Chen Y, et al. Outcomes of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in 107 patients with cancer from Wuhan, China. Cancer. 2020;126(17):4023–4031. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robilotti EV, Babady NE, Mead PA, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1218–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yarza R, Bover M, Paredes D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in Cancer patients undergoing active treatment: analysis of clinical features and predictive factors for severe respiratory failure and death. Eur J Cancer. 2020;135:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Chen L, Li Q, et al. Cancer increases risk of in-hospital death from COVID-19 in persons <65 years and those not in complete remission. Leukemia. 2020;34(9):2384–2391. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0986-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jee J, Foote MB, Lumish M, et al. Chemotherapy and COVID-19 outcomes in patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(30):3538–3546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Pina JM, Rodríguez Rodriguez M, Castro Quismondo N, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality from COVID-19 in patients with Haematological malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2020;105(5):597–607. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assaad S, Avrillon V, Fournier ML, et al. High mortality rate in Cancer patients with symptoms of COVID-19 with or without detectable SARS-COV-2 on RT-PCR. Eur J Cancer. 2020;135:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garassino MC, Whisenant JG, Huang LC, et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):914–922. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma J, Yin J, Qian Y, Wu Y. Clinical characteristics and prognosis in cancer patients with COVID-19: a single center’s retrospective study. J Inf Secur. 2020;81(2):318–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox TA, Troy-Barnes E, Kirkwood AA, et al. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for severe COVID-19 in patients with Haematological disorders receiving chemo-or immunotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2020;191(2):194–206. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Booth S, Willan J, Wong H, et al. Regional outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in hospitalised patients with Haematological malignancy. Eur J Haematol. 2020;105(4):476–483. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cattaneo C, Daffini R, Pagani C, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in Dematologic patients affected by COVID-19. Cancer. 2020;126(23):5069–5076. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lara OD, O'Cearbhaill RE, Smith MJ, et al. COVID-19 outcomes of patients with gynecologic cancer in New York City. Cancer. 2020;126(19):4294–4303. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Li L, Song K, et al. A nomogram for predicting mortality in patients with COVID-19 and solid tumors: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001314. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo J, Rizvi H, Preeshagul IR, et al. COVID-19 in patients with lung Cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(10):1386–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mato AR, Roeker LE, Lamanna N, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with CLL: a multicenter international experience. Blood. 2020;136(10):1134–1143. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogado J, Obispo B, Pangua C, et al. Covid-19 transmission, outcome and associated risk factors in cancer patients at the first month of the pandemic in a Spanish hospital in Madrid. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(12):2364–2368. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell B, Moss C, Papa S, et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 outcomes in cancer patients: a first report from Guy’s cancer center in London. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1279. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scarfò L, Chatzikonstantinou T, Rigolin GM, et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a joint study by ERIC, the European research initiative on CLL, and CLL campus. Leukemia. 2020;34(9):2354–2363. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0959-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vuagnat P, Frelaut M, Ramtohul T, et al. COVID-19 in breast Cancer patients: a cohort at the Institut curie hospitals in the Paris area. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang B, Van Oekelen O, Mouhieddine TH, et al. A tertiary center experience of multiple myeloma patients with COVID-19: lessons learned and the path forward. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00934-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Song Q, Chen Y, et al. Systematic investigations of COVID-19 in 283 cancer patients. medRxiv. 2020; 10.1101/2020.04.28.20083246

- 45.Gonzalez-Cao M, Carrera C, Rodriguez Moreno JF, et al. COVID-19 in melanoma patients: Results of the Spanish Melanoma Group Registry, GRAVID study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(5):1412–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.de Melo AC, LCS T, da Silva JL, et al. Brazilian National Cancer Institute COVID-19 task force. Cancer inpatient with COVID-19: a report from the Brazilian National Cancer Institute. Plos One. 2020;15(10):e0241261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albiges L, Foulon S, Bayle A, et al. Determinants of the outcomes of patients with cancer infected with SARS-CoV-2: results from the Gustave Roussy cohort. Nature Cancer. 2020;1:965–975. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martínez-López J, Mateos MV, Encinas Giannakoulis VGC, et al. Multiple myeloma and SARS-CoV-2 infection: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of inpatient mortality. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(10):103. doi: 10.1038/s41408-020-00372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martín-Moro F, Núnez-Torrón C, Pérez-Lamas L, et al. Survival study of hospitalised patients with concurrent COVID-19 and Haematological malignancies. Leuk Res. 2021;101:106518. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lattenist R, Yildiz H, De Greef J, Bailly S, Yombi JC. COVID-19 in adult patients with hematological disease: analysis of clinical characteristics and outcomes. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2020;37(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12288-020-01318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakamura S, Kanemasa Y, Atsuta Y, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with cancer: a single-center retrospective observational study in Tokyo, Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26(3):485–493. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01837-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogiers A, Pires da Silva I, Tentori C, et al. Clinical Impact of COVID-19 on Patients with Cancer Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(1):e001931. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nie L, Dai K, Wu J, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for in-hospital mortality of lung cancer patients with COVID-19: a multicenter, retrospective, cohort study. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12(1):57–65. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larfors G, Pahnke S, State M, Fredriksson K, Pettersson D. Covid-19 intensive care admissions and mortality among Swedish patients with cancer. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(1):32–34. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1854481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Höllein A, Bojko P, Schulz S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with cancer and COVID-19: results from a cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(1):24–27. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1863464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garnett C, Foldes D, Bailey C, et al. Outcome of hospitalized patients with hematological malignancies and COVID-19 infection in a large urban healthcare trust in the United Kingdom. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62(2):469–472. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1838506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanna GJ, Rettig EM, Park JC, et al. Hospitalization rates and 30-day all-cause mortality among head and neck cancer patients and survivors with COVID-19. Oral Oncol. 2021;112:105087. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lièvre A, Turpin A, Ray-Coquard I, et al. GCO-002 CACOVID-19 collaborators/investigators. Risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality among solid Cancer patients and impact of the disease on anticancer treatment: a French Nationwide cohort study (GCO-002 CACOVID-19) Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:62–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith M, Lara OD, O'Cearbhaill R, et al. Inflammatory markers in gynecologic oncology patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159(3):618–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu Y, Chen W, Li W, et al. Clinical characteristics, therapeutic management, and prognostic factors of adult COVID-19 inpatients with hematological malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(14):3440–3450. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1808204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yekedüz E, Utkan G, Ürün Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis: the effect of active cancer treatment on severity of COVID-19. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.May JE, Donaldson C, Gynn L, Morse HR. Chemotherapy-induced Genotoxic Damage to Bone Marrow Cells: Long-term Implications. Mutagenesis. 2018;33(3):241–251. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gey014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gardner RV. Long term hematopoietic damage after chemotherapy and cytokine. Front Biosci. 1999;4:e47–e57. doi: 10.2741/A479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vento S, Cainelli F, Temesgen Z. Lung infections after cancer chemotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(10):982–992. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang DH, Weaver MT, Park NJ, Smith B, McArdle T, Carpenter J. Significant impairment in immune recovery after Cancer treatment. Nurs Res. 2009;58(2):105–114. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcecd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi Y, Wang Y, Shao C, et al. COVID-19 infection: the perspectives on immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(5):1451–1454. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-0530-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lord JM, Midwinter MJ, Chen YF, et al. The systemic immune response to trauma: an overview of pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet. 2014;384(9952):1455–1465. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to Cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.