Abstract

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a rare small-vessel vasculitis associated with high mortality without appropriate treatment. Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has been reported as an atypical presentation of GPA. We report a case of STEMI, shortly followed by subacute in-stent thrombosis with extensive thrombus burden in a 53-year-old male patient with undiagnosed GPA. After aggressive treatment with triple therapy consisting of aspirin, clopidogrel and rivaroxaban, He started to have haemoptysis. Despite the discontinuation of aspirin, he ended up with massive haemoptysis and acute respiratory failure necessitating endotracheal intubation. CT of the chest revealed bilateral ground-glass opacities consistent with diffuse alveolar haemorrhage. Extensive workup revealed positive antiproteinase 3 antibodies; hence, a diagnosis of GPA was made. He was treated with induction therapy consisting of methylprednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide and rituximab, leading to a gradual improvement in his clinical conditions and subsequent extubation.

Keywords: interventional cardiology, cardiovascular medicine, vasculitis, interstitial lung disease

Background

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, is a multisystem vasculitic disease characterised by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of small to medium-sized blood vessels.1 Typical manifestations include respiratory tract and renal involvements, such that the incidence of eye, nose, throat and constitutional symptoms have been reported in more than 80% of patients.1 Coronary artery disease was documented in only 0.38% from a North American GPA cohort of 517 patients,2 and there are only a few case reports demonstrating acute myocardial infarction as an initial presentation of GPA.3–7 The administration of antithrombotic therapy in active pulmonary vasculitides could inadvertently aggravate a devastating complication known as diffuse alveolar haemorrhage. We presented a patient with recurrent ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) who was transferred to our facility with haemoptysis that progressed to massive haemoptysis from diffuse alveolar haemorrhage due to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-positive GPA.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old man with a medical history of well-controlled hypertension and dyslipidaemia presented with a 1-week history of haemoptysis. Three weeks earlier, he had substernal pain due to anterior STEMI, for which a proximal LAD stent was placed and he was given aspirin and clopidogrel. A week later, despite being compliant to medications, he presented again with recurrent chest pain on exertion and a new onset ST-segment elevation in anterior leads. Coronary angiography revealed in-stent thrombosis with extensive thrombus extending from proximal to distal LAD. Transcatheter thrombectomy with additional stent placement was performed and he was discharged on triple therapy consisting of aspirin, clopidogrel and rivaroxaban. Afterwards, he started to develop mild haemoptysis, leading to discontinuation of aspirin. Eventually, he was re-hospitalised with massive haemoptysis and acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure.

Investigations

An official coronary angiographic report from outside facility revealed a total occlusion due to in-stent thrombosis in proximal segment, together with new thrombotic occlusion across mid to distal segment of LAD. Transcatheter thrombectomy, with plain old balloon angioplasty in distal LAD, and intracoronary stent placement (3.0×18 mm and 4.0×26 mm Resolute Onyx stent in proximal and mid LAD, respectively) were performed.

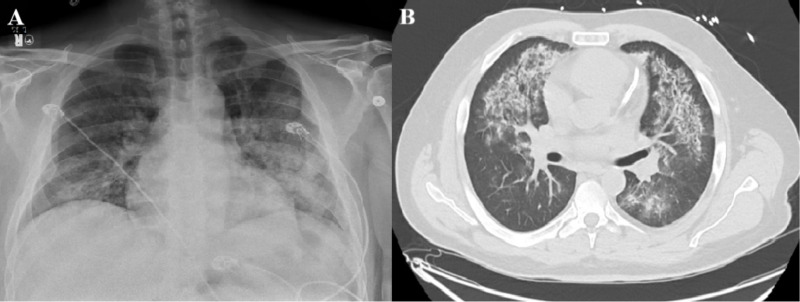

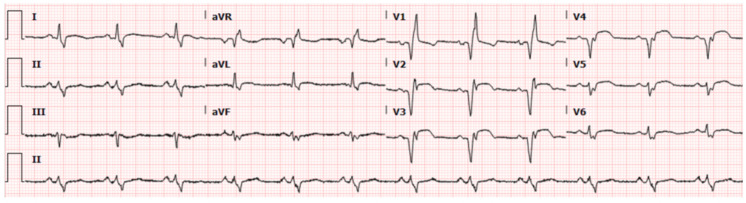

The admission chest X-ray revealed diffuse alveolar opacification in both lungs with a predilection towards the middle and lower lung zones (figure 1A). CT scan of the chest showed bilateral areas of ground-glass opacities consistent with diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (figure 1B). There was an evidence of ST-segment elevation on anterior chest leads on the ECG (figure 2). Patient had normocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 85 g/L), high-normal platelet count (422×109/L) and normal white cell count (7.5×109/L). There were haematuria (red blood cells: 25–50/hpf) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL) without glucosuria, nitrite or leucocyte esterase. Elevated kidney markers (urea: 28 mg/dL, creatinine: 1.6 mg/dL) and inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 71 mm/hour, C reactive protein 12.4 mg/dL) were documented. Serological studies were negative for hepatitis-B, hepatitis-C, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-glomerular membrane antibody (anti-GBM) and anti-myeloperoxidase antibody (anti-MPO). Anti-proteinase 3 antibody and rheumatoid factor were tested positive (5.6 AI and 482 IU/mL, respectively).

Figure 1.

(A) Chest X-ray revealing diffuse bilateral opacifications with relative apical sparing. (B) CT of the chest revealing diffuse bilateral ground-glass appearance with evidence of coronary stent in the left anterior descending artery.

Figure 2.

ECG demonstrating ST-segment elevation in V2-V6.

Treatment

In addition to respiratory support with mechanical ventilation, he was commenced on a combination of immunosuppressive therapies consisting of methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil. Although guidelines recommended methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide with plasmapheresis as the standard of care, plasmapheresis was unfortunately unavailable at that time so we added mycophenolate mofetil for further immunosuppression. Nevertheless, there was no significant improvement in his clinical conditions after 5 days. Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage and hypoxaemic respiratory failure persisted despite normalisation of kidney functions; therefore, additional immunosuppression with rituximab was given. Eventually, the inflammatory markers gradually declined and successful extubation was achieved after 12 days of intubation. Tapered dose of prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil were continuously given to induce remission.

Recent large trials demonstrated the superior efficacy of clopidogrel compared with aspirin monotherapy in preventing the composite endpoint of death, recurrent myocardial infarction and stroke, together with lower bleeding risks, in patients with drug-eluting stent who had already completed 6–18 months of dual antiplatelet therapy.8–10 Although the clinical setting is different from our patient, we decided to use clopidogrel monotherapy for the prevention of recurrent STEMI due to its superior antiplatelet activity and lower risk of bleeding.

Outcome and follow-up

He was hospitalised for a total of 29 days. He developed massive haemoptysis and acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure on the second day of hospitalisation. He was extubated after 12 days, after which he continued to have mild haemoptysis and required oxygen supplement through nasal cannula. The hospital course was complicated by paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcal bacteraemia. As the risks of bleeding outweighed the benefits, he was not commenced on anticoagulant. There was no evidence of infective bacterial endocarditis, and a 14-day course of intravenous nafcillin successfully eradicated the bacteraemia.

He was re-hospitalised 5 days after hospital discharge due to worsening breathlessness and desaturation from acute decompensated heart failure. Comprehensive investigation revealed no evidence suggestive of vasculitic flare. Transthoracic echocardiography showed impaired left ventricular ejection fraction at 30%–34%. His clinical condition rapidly improved after diuretic treatment. He was discharged with optimal guideline-directed medical therapy.

Discussion

Acute coronary syndrome is a rare clinical presentation of GPA. The underlying mechanisms might be explained by direct coronary vasculitis or indirectly through systemic inflammation-mediated accelerated atherosclerosis and thrombosis.6 7 11 An evidence of systemic inflammation and aggravated vascular remodelling associated with increased intima-media thickness was documented in patients with GPA.11 In ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), fibrin, a product involved in a final pathway of coagulation cascade, is found in the inflamed vessels as a result of fibrinoid necrosis.12 A disruption of the endothelium results in the exposure of thrombogenic tissue factor which triggers the coagulation cascade. Additionally, there is an evidence showing that the circulatory levels of detached endothelial cells, which may be responsible for distant thrombosis, are higher in those with AAV.12 Interestingly, the risk of thromboembolism persists even in remission due to the presence of anti-plasminogen antibodies.13 Only limited evidence exists in terms of the incidence of acute coronary syndrome in patients with GPA. Severe coronary vasculitis resulting in cardiogenic shock was reported in a case of 50-year-old man with chronic sinusitis and worsening constitutional symptoms.6 Similar to our patient, there was a report of recurrent STEMI due to thrombosis in multiple segments of angiographically normal coronary arteries in a 58-year-old woman without known cardiac risk factors.7

Making a diagnosis of GPA in our patient; however, can be difficult initially, as he presented with a life-threatening anterior wall STEMI. In a real-life setting, the abnormalities in his urinalysis might unintendedly go unnoticed. This patient also lacks typical manifestations of GPA such as sinusitis, palpable purpura or mononeuritis multiplex. Additionally, elevated creatinine levels and haematuria are non-specific and can also be seen in acute kidney injury aggravated by decreased cardiac output. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein are helpful in diagnosing underlying systemic vasculitis despite lacking specificity.14 This patient has an active pulmonary-renal syndrome with elevated inflammatory markers. Other possible causes have been excluded as evidenced by negative serological markers including ANA, anti-GBM and anti-MPO. Viral hepatitis, which is reportedly associated with polyarteritis nodosa and cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis,15 was also tested negative.

Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage, a devastating condition associated with high morbidity and mortality, occurs as a consequence of ANCA-mediated leucocytoclastic vasculitis of the pulmonary microcirculation including alveolar arterioles, capillaries and venules.14 Although rare, bland pulmonary haemorrhage attributable to dual antiplatelet (ie, aspirin and thienopyridine) following stent placement has also been previously reported in patients without underlying vasculitides.16 17 There was a strong evidence, from a large cohort of patients with acute coronary syndrome taking antithrombotic agents, demonstrating the dose-related association between bleeding risk and death.18 Clinicians must always consider the possibility of diffuse alveolar haemorrhage in all patients receiving a combination of antiplatelets and anticoagulants following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with additional attention given to those with suspected systemic vasculitic diseases.19 Thorough history taking, physical examination and laboratory investigations are obligatory in diagnosing and preventing this rare but fatal complication.

Learning points.

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for the possibility of non-atherosclerotic coronary stenosis as in cases of coronary vasculitis for early detection and management of a potentially fatal but reversible condition.

The development of heavy thrombotic burden, let alone an in-stent thrombosis, in patients who are well-compliant to antiplatelet medications should raise concern for secondary causes of ST- elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) including vasculitis.

Careful monitoring for bleeding complications in acute coronary syndrome patients receiving antithrombotic medications is imperative for early detection and discontinuation of the offending agents.

The most appropriate treatment in preventing recurrent STEMI and minimising the bleeding risk in patients with vasculitis complicated by diffuse alveolar haemorrhage remains to be clarified.

Footnotes

Twitter: @poemlarp

Contributors: JB drafted the manuscript. MHA, PM and MMA revised the manuscript. MMA gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Grygiel-Górniak B, Limphaibool N, Perkowska K, et al. Clinical manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis: key considerations and major features. Postgrad Med 2018;130:581–96. 10.1080/00325481.2018.1503920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGeoch L, Carette S, Cuthbertson D, et al. Cardiac involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1209–12. 10.3899/jrheum.141513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazarus MN, Khurana R, Sethi AS, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting with an acute ST-elevation myocardial infarct (STEMI). Rheumatology 2006;45:916–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatenby PA, Lytton DG, Bulteau VG, et al. Myocardial infarction in Wegener's granulomatosis. Aust N Z J Med 1976;6:336–40. 10.1111/imj.1976.6.4.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt G, Gareis R, Störk T. Direct percutaneous coronary intervention for NSTEMI in a patient with seropositive Wegener's granulomatosis. Z Kardiol 2005;94:583–7. 10.1007/s00392-005-0271-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raghunathan V, Pelcovits A, Gutman D, et al. Cardiogenic shock from coronary vasculitis in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017. 10.1136/bcr-2017-220233. [Epub ahead of print: 29 Jun 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah AH, Kinnaird TD. Recurrent ST elevation myocardial infarction: what is the aetiology? Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:e169–72. 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.04.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo B-K, Kang J, Park KW, et al. Aspirin versus clopidogrel for chronic maintenance monotherapy after percutaneous coronary intervention (HOST-EXAM): an investigator-initiated, prospective, randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet 2021;397:2487–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01063-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park H-W, Kang M-G, Ahn J-H, et al. Effects of monotherapy with clopidogrel vs. aspirin on vascular function and hemostatic measurements in patients with coronary artery disease: the prospective, crossover I-LOVE-MONO trial. J Clin Med 2021;10:2720. 10.3390/jcm10122720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park TK, Song YB, Ahn J, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin as an antiplatelet monotherapy after 12-month Dual-Antiplatelet therapy in the era of drug-eluting stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:e002816. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Leeuw K, Sanders J-S, Stegeman C, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with Wegener's granulomatosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:753–9. 10.1136/ard.2004.029033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomasson G, Monach PA, Merkel PA. Thromboembolic disease in vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2009;21:41–6. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32831de4e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misra DP, Thomas KN, Gasparyan AY, et al. Mechanisms of thrombosis in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:4807–15. 10.1007/s10067-021-05790-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park MS. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Tuberc Respir Dis 2013;74:151–62. 10.4046/trd.2013.74.4.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ragab G, Hussein MA. Vasculitic syndromes in hepatitis C virus: a review. J Adv Res 2017;8:99–111. 10.1016/j.jare.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda M, Tanaka H, Sadamatsu K. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage as a complication of dual antiplatelet therapy for acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2011;12:407–11. 10.1016/j.carrev.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oualim S, Elharda CA, Benzeroual D, et al. Pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage mimicking a pneumopathy: a rare complication of dual antiplatelet therapy for ST elevation myocardial infarction. Pan Afr Med J 2016;24:308. 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.308.8828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, et al. Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2006;114:774–82. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.612812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause ML, Cartin-Ceba R, Specks U, et al. Update on diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary vasculitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2012;32:587–600. 10.1016/j.iac.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]