Abstract

A 74-year-old man was being investigated for a pancreatic insulinoma when an incidental mesenteric mass measuring 2.6 cm x 2.5 cm was noticed on CT imaging. A wait-and-see approach was decided on. Thirty-nine months later, the patient presented with symptoms of abdominal obstruction. CT images revealed the mesenteric mass filled majority of the abdominal cavity and measured 29 cm x 26 cm x 16 cm. The patient underwent an open bypass gastrojejunostomy which stopped working a few weeks later due to further compression by the tumour. A debulking surgery was performed: a right hemicolectomy and small bowel resection with excision of the desmoid tumour and bypass gastrojejunostomy. The tumour measured 12.6 kg and was macroscopically visualised to have a white cut surface with a focal translucent area. Microscopic analysis revealed bland spindle cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm showing no cytological atypia, in keeping with a mesenteric desmoid tumour. Currently, two and a half years from the debulking surgery, the patient remains well and in remission with planned surveillance.

Keywords: oncology, surgery, gastrointestinal surgery

Background

Desmoid tumours are very rare, accounting for 0.03% of all neoplasms and less than 3% of all soft tissue tumours. Their annual incidence is estimated to be 2–4 cases per million per year in the general population.1 They are well-differentiated fibromatous tumours resulting from abnormal proliferation of myofibroblasts.2 Factors linked to the development of desmoid tumours include hormonal influence such as pregnancy, trauma and hereditary cancer syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Gardner’s syndrome.3 These tumours are benign and often asymptomatic but can be locally destructive requiring surgical intervention due to small bowel obstruction, perforation and abscess formation.1 4 We present the case of a 74-year-old man who developed small bowel obstruction secondary to a large desmoid tumour of the small intestine mesentery.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old man presented to our hospital in London, UK with episodes of repeated hypoglycaemia. His medical history otherwise included hypertension, colonic polyps and prostate cancer. No abdominal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting or pain were recorded. He underwent CT pancreas to investigate insulinoma as cause of the hypoglycaemia which revealed an incidental 2.6×2.5 cm soft tissue mass arising from the mesentery. Four months on, follow-up CT revealed an increase in the mesenteric mass to 2.8 cm and 13 months after that, the mass measured 4.2 cm in maximal length (figures 1 and 2). No other changes were recorded. In the interim, a pancreatic islet cell tumour was confirmed and treated medically with diazoxide. The mesenteric mass was monitored.

Figure 1.

Early cross-sectional CT image of desmoid tumour.

Figure 2.

Early coronal CT image of desmoid tumour.

Thirty-four months from initial presentation, the patient presented with vomiting, colicky abdominal pain and abdominal distension. Abdominal X-ray and CT confirmed small bowel obstruction. The mesenteric mass now measured 9cm x 5 cm x 7.2 cm and was inseparable from the duodenum. The patient was otherwise stable and opening his bowels, so he was managed conservatively, and he recovered. The consensus from the colorectal and hepatobiliary multidisciplinary teams (MDT) were given the extensive nature of the disease alongside fistulation to duodenum, he was not suitable for surgery.

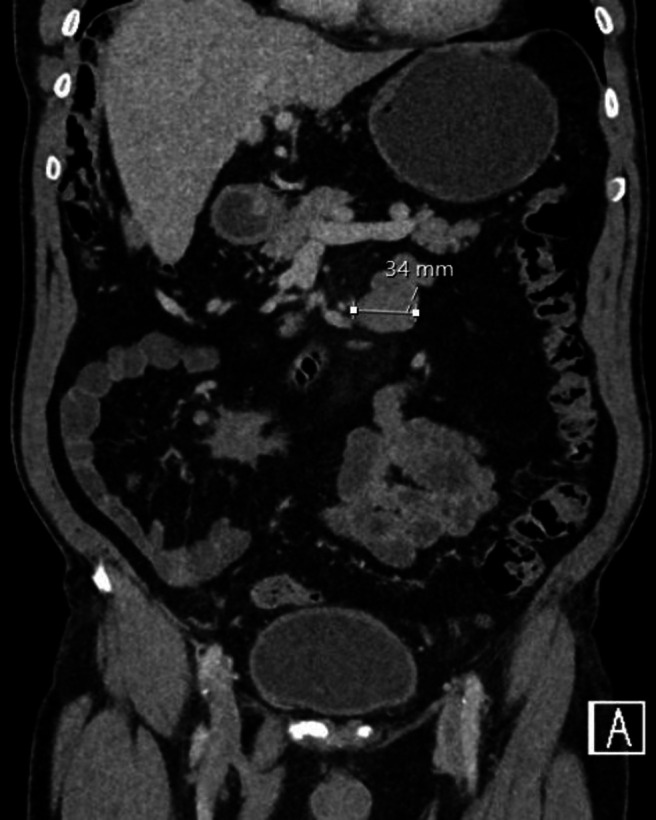

Five months later (39 months after initial presentation), the patient presented with abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and had not opened his bowels for 3 days. CT at this point revealed a significant increase in the size of mesenteric mass, occupying majority of the abdomen and measuring 29 cm x 26 cm x 16 cm. The mass completely encased D3, and D4 could not be delineated separately. There was tethering of both the jejunum and ileum to the mesenteric mass. It was decided that surgery would be the best course of action. The patient underwent an open bypass gastrojejunostomy. The operation was successful, and no complications were recorded.

Approximately 1 month after the operation, the gastrojejunostomy bypass was not working due to compression by the large mesenteric tumour as shown in the CT images (figures 3–5). A second surgery was planned to debulk the tumour. This 7.5-hour operation included a right hemicolectomy and small bowel resection with excision of the desmoid tumour and bypass gastrojejunostomy. Unfortunately, the patient sustained a postoperative leak and intra-abdominal sepsis requiring a third operation: a laparotomy and washout and ileostomy and mucous fistula formation.

Figure 3.

Coronal CT image of large desmoid tumour before debulking surgery.

Figure 4.

Sagittal CT image of large desmoid tumour.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional CT image of large desmoid tumour.

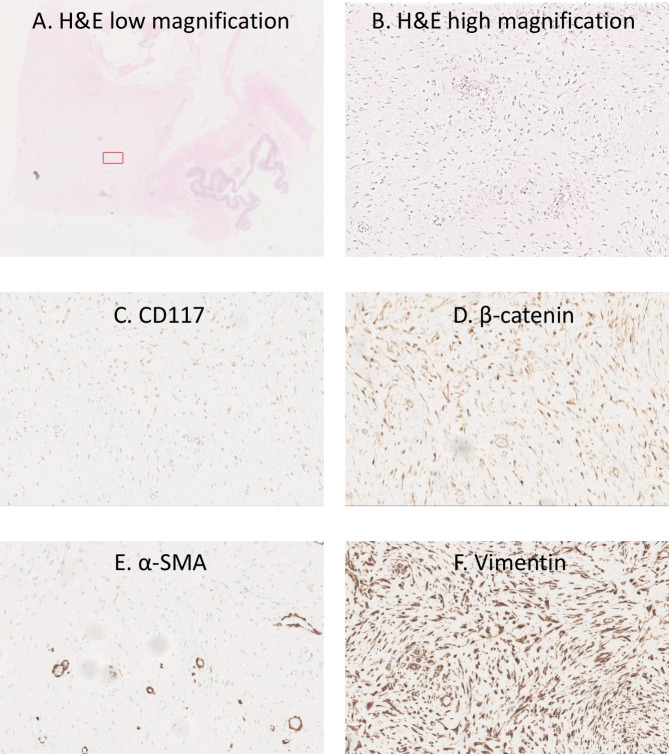

The tumour measured 12.6 kg and was macroscopically visualised to have a white cut surface with a focal translucent area. Microscopic analysis revealed bland spindle cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm showing no cytological atypia, which were strongly positive for vimentin and with focal smooth muscle actin and beta catenin positivity (figure 6). No significant mitotic activity was seen. Findings were in keeping with a mesenteric desmoid tumour. Right hemicolectomy showed no significant histological abnormality. The patient showed improvement over a prolonged hospital stay of 7 months. He was then discharged and brought back 2 months later for a laparotomy and reversal of ileostomy. This was performed successfully, and the patient recovered well.

Figure 6.

Histopathological images of desmoid tumour. (A) H&E low-magnfiication (1x) of whole slide with bowel on bottom right hand side and highlighted red box for higher power magnification of subsequent slides. (B) H&E high-magnification (40x) of highlighted area in (A) showing pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with no cytological atypia. (C) Immunostaining demonstrating no staining for CD117. (D) Immunostaining showing focal beta-catenin staining. (E) Immunostaining showing focal alpha smooth muscle actin staining. (F) Immunostaining showing intense vimentin staining.

Currently, two and a half years after the debulking tumour, the patient remains well and in remission. Following discharge, he had follow-up surveillance scans every 6 months for the first 18 months which showed no recurrence of the desmoid tumour. He is planned for a once yearly surveillance scan.

Discussion

A detailed literature search was conducted on PubMed using the terms ‘Desmoid Tumour’ AND ‘small intestine’ OR ‘small bowel’ OR ‘mesentery’ OR ‘intra-abdominal’ OR ‘abdomen’ AND ‘case report’ in either the title or abstract. A total of 56 publications were found dating from 1980 to 2021. Inclusion criteria was set to English language, full-text publications and case-reports. Further to that, seven publications were excluded on the basis that five were paediatric cases and two were focused on non-desmoid tumours. This gave a total of 49 publications (describing a total of 56 individual cases) which are detailed in table 1. Median age of presentation was 47 (IQR 36.5–59) years with a 4:3 male preponderance. Median size of tumour excised was 8 (IQR 3–14) cm. Intra-abdominal tumour location was the the most common.

Table 1.

Summary of desmoid tumour cases described in the literature

| Year | Author | Age | Gender | Presentation | Intraoperative findings and organ involvement | Tumour size (cm) | Operation | Outcome |

| 2021 | Tchangai et al5 | 40 | F | Abdominal distension, constipation, difficulty voiding, weight loss | Firm multilobed mass that contracted adhesions with the pelvic colon, right ureter and rectum. | 40 | Laparotomy and resection through a combined perineal approach. | Alive |

| 2021 | Park et al6 | 23 | F | Epigastric pain | Mass involving distal pancreas, invasive to the posterior wall of the antrum of the stomach and transverse colon and fourth portion of the duodenum. | 10 | Distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy and combined partial resection of the stomach, transverse colon and fourth portion of the duodenum. | Alive |

| 2021 | Pop et al7 | 38 | F | Abdominal pain, asthenia, loss of appetite | The mass localised at the level of the jejunal mesentery, in tight contact with the duodenum and the mesenteric vessels. | 7 | ‘En bloc’ resection of the tumour, together with the involved enteral loops followed by end-to-end anastomosis of the jejunum. | Alive |

| 2021 | Mitrovic et al8 | 37 | F | Epigastric pain, palpable mass in the right hemiabdomen | Well-marginated mass that invaded the wall of the caecum and small bowel mesentery near the terminal ileum. | 11 | Hemicolectomy with partial resection of the terminal ileum with latero-lateral ileocolonic anastomosis. | Alive |

| 2021 | Omori et al9 | 46 | M | Fever, right lower quadrant pain | The scar tissue related to the abscess was attached to the lateral wall of the ascending colon and spread to the retroperitoneum. A portion had infiltrated the muscularis propria of the ascending colon and had formed a fistula. | 5.4 | Right colectomy with abscess resection. | Alive |

| 2021 | Laurens et al10 | 56 | F | Nausea, distended abdomen | Mass adhered to a loop of small bowel, a short segment of transverse colon and three sections of omentum. | ‘Grapefruit’ | Laparotomy and mass excision and bowel anastomoses. | Alive |

| 2020 | Jin et al11 | 28 | F (pregnant at 32 weeks) | Abdominal pain | Left side of the uterus. | 30 | Resection. | Alive |

| 2020 | Deshpande et al12 | 44 | F | Abdominal discomfort | Multiple soft tissue masses attached to the wall of small intestine and invading the surrounding mesentery. | 11 | Resection of a large segment of small intestine. | Alive |

| 2020 | Khanna et al13 | 45 | M | Periumbilical pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite | Large, heterogeneous mass arising from the body of the pancreas. The mass was predominantly solid with a small cystic component abutting the stomach and duodenum with loss of intervening fat planes. There was moderate to severe narrowing of the portal venous confluence and adjacent segments of the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein. | 12 | Radical resection of the mass with distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, partial gastrectomy, duodenectomy of the fourth portion of duodenum and resection of portal vein with interposition of deep femoral vein graft from superior mesenteric vein to portal vein. | Alive |

| 2020 | Omi et al14 | 47 | F | Left back pain | Adherence of the tumour to the rectum and left ureter but no dissemination or metastasis. The tumour was located at the left obturator fossa, involved the rectum and left ureter and was fixed to the left pelvic sidewall due to infiltration to the left parametrium. | 3 | Laparoscopic resection of the left adnexa, left parametrium and combined resection of the left ureter and rectum. | Alive |

| 2020 | Sierra-Davidson et al15 | 27 | F | Left upper quadrant pain, palpable mass (post-Roux-en-Y bypass surgery) | The mass arose from the proximal small bowel and extended from the root of the mesentery to within 1 cm of the bowel wall. The mass was firmly adherent to the Roux limb, as well as the jejunojejunostomy and distal portion of the biliopancreatic limb. The distal small bowel was not involved. | 16 | The mass was resected en bloc with the entire Roux limb and the jejunojejunostomy. The RYGB was reconstructed in an antecolic antegastric fashion. The gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy were then recreated. | Alive |

| 2020 | Mahnashi et al16 | 48 | M | Abdominal pain (epigastrium and left hypochondrium), discomfort | The mass arose from the jejunal wall with a highly vascular smooth surface and a well-defined margin at the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis. The mass had a large feeding arterial supply arising from the mesentery of the small bowel. Another mass was found distal to the gastrojejunostomy. | 15.8 | Laparoscopic exploration converted to laparotomy. Surgical resection was performed, and the gastrojejunal anastomosis was disconnected from the distal stomach pouch. A Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was done. | Alive |

| 2019 | Asenov et al17 | 27 | M | Right lower quadrant and suprapubic pain | Tumour involved the jejunum in its proximal third. The affected loop was situated near the ileocecal confluence. | Not specified | Laparotomy and resection of the small bowel. | Alive |

| 2019 | Ebeling et al18 | 59 | M | Right lower quadrant pain, abdominal distension, urinary urgency | Mass from mid-jejunum that displaced the bowel but did not invade adjacent structures. | 18 | Exploratory laparotomy and mass resection—segmental enterectomy with primary stapled anastomosis. | Alive |

| 2019 | Mastoraki et al19 | 36 | M | Abdominal pain, palpable mass in left abdomen |

|

12.5 |

|

Alive |

| 2018 | Stickar et al20 | 76 | M | Fever, abdominal distension, palpable mass in hypogastrium | Mass arose from the jejunum, 20 cm from the duodenojejunal angle. | 15 | Intestinal resection lateral–lateral mechanical anastomosis. | Alive |

| 2018 | Akbulut et al21 | 46 | F | Postprandial nausea and vomiting | The mass originated from the pancreatic body, adhering to the prepyloric antrum of the stomach and forming a conglomerated structure with the fourth part of the duodenum and proximal jejunal loops. | 12 | Laparotomy with conglomerated fourth part of the duodenum, proximal jejunum, distal pancreas and the spleen were removed en-bloc. End-to-end anastomosis was formed between the third part of duodenum and proximal jejunum. | Alive |

| 2018 | Burke et al22 | 46 | M | Upper abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, early satiety | The mass projected from the mesenteric fat and infiltrated surrounding structures including the small bowel and caecum. It had encased around the SMA and SMV, compromising blood supply to the small bowel. | 5.6 | Laparotomy with excision of this mesenteric mass—an extended right hemicolectomy, small bowel resection, jejuno-jejunal anastomosis and an ileo-colic anastomosis. | Alive |

| 2018 | Lee et al23 | 46 | M | Left lower quadrant pain, palpable mass in the left upper abdomen | The mass arose from the retroperitoneum, closely related to the pancreas tail. The boundary between the mass and adjacent pancreas parenchyma was indistinct. | 21.5 | Laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy without preoperative biopsy due to a risk of rupture. | Alive |

| 2018 | Ogawa24 | 35 | F | Abdominal pain | The tumours were extensively integrated throughout the rectus abdominis and transverse abdominal muscles. | 15 | Detectable tumours were resected resulting complete removal of her rectus abdominis muscle, including the anterior and posterior sheaths and parts of her transverse abdominal muscle. Partial colectomy for transverse colon that strongly adhered to some tumours. | Alive |

| 2017 | Jafri et al25 | 54 | F | Dysphagia, weight loss | Irregular, ill-defined mass at the head of the pancreas causing complete bile and pancreatic duct obstruction. | 5.2 | Whipple with end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy, cholecystectomy, an end-to-side choledochojejunostomy, a wedge liver biopsy of segment 3, a biopsy of the superior pancreatic lymph node and a retrocolic end-to-end gastrojejunostomy. | Alive |

| 2017 | Lu et al26 | 47 | F | Abdominal pain | Posterior wall of the antrum. | 4.5 | Distal gastrectomy (Billroth-I). | Alive |

| 2016 | Nagata et al27 | 49 | M | Ileus symptoms | Recurrent mesenteric tumours with adhesion to the intestinal tract and peritoneum. | 12 | Initial: duodenojejunostomy. Current: surgically unresectable. | Alive |

| 2015 | Sugrue et al28 | 71 | M | Abdominal pain | The mass originated from the jejunal mesentery with a 25 cm loop of jejunum firmly adherent to the mass approximately 15–20 cm from the ligament of Treitz. Left-sided tumour adherent to the left abdominal wall, mesentery, omentum and small bowel. | 24 | The piece of the jejunum that was adherent to the mass was resected, and the mass was removed en bloc from the abdominal cavity with primary, side-to-side stapled small bowel anastomosis. | Alive |

| 2015 | Bn et al29 | 24 | M | Abdominal pain, distention | The tumour extended from L2–L5 to posterior part of abdominal wall. | 16.4 | Laparotomy with mass excised and mesentery repaired. | Alive |

| 2014 | D et al30 | 29 | M | Swelling in the right side of umbilicus | Intraperitoneal cavity with retroperitoneal extension. | 6 | Exploratory laparotomy with excision of mass in ileal mesentery—excised along with 20 cm of ileum and end to end anastomosis in two layers. | Alive |

| 2014 | Fleetwood et al31 | 60 | M | Right upper quadrant pain | The mass was inseparably adherent to the small bowel and the mesentery. | 13 | Laparotomy and resection en bloc with the mass. | Alive |

| 2013 | Monneur et al32 | 21 | M | Abdominal pain, vomiting, pyrosis, constipation, increase of abdomen volume | Intra-abdominal tumour close to the stomach (origin difficult to assess). | 3.2 | No operation—medically treated. | Alive |

| 2012 | Peled et al33 | 32 | M | Abdominal pain, fever | A large submucosal mass obstructed the appendix orifice. The appendix was dilated. A large abscess was attached to the lateral wall of the cecum along the appendix. | 8 | Right hemicolectomy. | Alive |

| 2010 | Basdanis et al34 | 52 | M | Acute epigastric pain, obstructive ileum | The large mesenteric mass occupied the left lateral abdominal quadrant and hypogastrium. | Not specified | Laparotomy with resection of tumour. | Alive |

| 2011 | Chang et al35 | 50 | M | Abdominal pain | The tumour arose from the antimesenteric side of the ileum 60–80 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. | Not specified | Laparotomy with resection of tumour and a segment of small bowel. | Alive |

| 2007 | Shah and Azam36 | 33 | M | Abdominal pain | Tumour located to ileum (25 cm proximal to the ileo-caecal valve on the mesenteric border). | 5 | Laparotomy and resection of 30 cm small bowel with a right hemicolectomy and side-to-side anastomosis. | Alive |

| 2008 | Tanaka et al37 | 73 | M | Swelling and pain of the right leg | Mass located to the right pelvis. | 9.5 | No operation—medically treated. | Alive |

| 2007 | Rakha et al38 | 38 | F |

|

|

|

|

Alive |

| 1993 | Disher et al39 | 18 | M | Weight loss, vomiting | The mass had a pedicle from the lower greater omentum and displaced both the common and internal iliac arteries. | 12.6 | Laparotomy with wide surgical resection. | Alive |

| 1980 | Logio et al40 | 60 | F | Abdominal pain | The tumour originated from the mesentery of mid-jejunum and infiltrated the bowel wall to the submucosa, interrupting continuity of the muscle coat. | 3 | Laparotomy and tumour dissection from mesenteric vascular pedicle, a 37-cm segment of jejunum and its mesentery and mesenteric nodes resected with end-to-end jejunostomy. | Alive |

| 2019 | Kim et al41 | 59 | F | Asymptomatic | Peritoneum, coeliac area. | 3.7 | Open biopsy. | Alive |

| 63 | F | Not specified | Peritoneum, pelvic area. | 2 | Small bowel resection and anastomosis, mass excision. | Alive | ||

| 58 | M | Not specified | Peritoneum, LUQ area. | 1.7 | Laparoscopic wedge resection of stomach, mass excision. | Alive | ||

| 50 | M | Not specified | Peritoneum, pelvic area. | 6.7 | Small bowel resection and anastomosis, mass excision. | Alive | ||

| 67 | M | Not specified | Peritoneum, pelvic area. | 2.2 | Excision of small bowel mesentery. | Alive | ||

| 56 | M | Not specified | Peritoneum, pelvic area. | 3 | Small bowel resection and anastomosis. | Alive | ||

| 40 | F | Asymptomatic | Peritoneum, pelvic area. | 3.3 | Small bowel resection and anastomosis. | Alive | ||

| 72 | M | Abdominal discomfort | Peritoneum, adrenal area. | 1.3 | Mass excision. | Alive | ||

| 2018 | Cheng et al42 | 34 | M | Palpable mass | The mass originated from the mesentery root, and adhered tightly to the descending duodenum, a portion of small intestine and the head of the pancreas. The SMA and SMV were engulfed by the tumour. | 20 | En bloc resection, including the whole small intestine, right and proximal transverse colon, while the SMA and SMV were resected at their root. | Alive |

| 2015 | Kim et al43 | 78 | M | Palpable mass | The tumour involved the external and internal oblique muscles above the transversus abdominis. | 4 | Diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed no peritoneal seeding lesions and no tumour invasion to the peritoneal surface. Metastatic lesion was resected. | Alive |

| 2015 | Efthimiopoulos et al44 | 40 | M | Palpable mass | A ‘tennis ball-shaped’ tumour of the mesentery close to the small intestine, 40 cm from the ileocecal valve. | 8.5 | A wide excision of the involved mesentery and adjacent small intestine with a side-to-side anastomosis between the proximal and the distal end of the small intestine. | Alive |

| 2014 | Palladino et al45 | 69 | M | Palpable mass | The tumour arose from the mesentery. It involved the duodenojejunal angle, and compressed the inferior vena cava. | 20 | Laparotomy and resection of large mesenteric mass with a part of the adherent jejunal and colic segment. | Dead-MI on postop day 1 |

| 2006 | Galeotti et al46 | 31 | F | Palpable mass | Mass located to left rectus muscle. | 10 | Laparotomy and removal whole thickness of the abdominal wall including the tumour. | Alive |

| 1991 | Umemoto et al47 | 37 | M | Palpable mass | Mass in abdominal wall, mesentery and retroperitoneum. | 12 | Laparotomy and tumour excision. | Alive |

| 2020 | Shayesteh et al48 | 64 | M | Incidental CT finding | Hypodense lesion in the body of the pancreas with the abutment of the splenic artery and vein. The surgical pathology showed intrapancreatic fibromatosis. | 2.9 | Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. | Alive |

| 2020 | Maemoto et al49 | 70 | F | Incidental CT finding | Presacral region below the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and involving the mesentery of the ileum. | 2.8 | Resection of the tumour combined with part of the mesentery. | Alive |

| 2019 | Muneer et al50 | 63 | F | Incidental finding during abdominoplasty for elective body-contouring surgery | Mass arose from the midline of the rectus sheath, in the para-umbilical region, both superior and inferior to the umbilicus. | 3 | The umbilicus was sacrificed and excised with the tumour, and neoumbilical reconstruction was done. The abdominal wall defect was closed primarily, and rectus sheath plication was performed. | Alive |

| 2014 | Kobayashi and Sugihara51 | 55 | M | Incidental CT finding | Duodenum and mesentery. | 1.2 | Laparotomy with tumour resection and wedge resection of the duodenum. | Alive |

| 2013 | Okamura et al52 | 57 | M | Incidental CT finding | Mesentery of the transverse colon. | 1.5 | Tumour resection and part of transverse colon was also removed. | Alive |

| 2012 | Shih et al53 | 56 | M | Incidental CT finding | The tumour was found in the retroperitoneum adhering to the peritumour vessels, nerves and the pancreatic tail. | 3.6 | Tumour resection en bloc with sacrifice of adjacent vessels and nerves. | Alive |

(a): Findings of initial tumour; (b): findings of tumour recurrence.

F, female; LUQ, Left Upper Qudratn; M, male; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; SMV, superior mesenteric vein.

From the literature, it was observed that most patients presenting with abdominal desmoid tumours complain of abdominal symptoms such as pain, nausea and loss of appetite.5–40 Of cases we analysed, 72.5% presented with abdominal symptoms. Other patients are asymptomatic, and the tumours are picked up either by a palpable mass,41–47 or incidental CT finding.48–53 Muneer et al describe an interesting case of a desmoid tumour discovered during an elective abdominoplasty for body-contouring surgery.50 Desmoid tumours are often diagnosed late due to the lack of specific symptoms and asymptomatic development. Asenov et al describe two major tumour characteristics that are responsible for the diverse clinical presentation: first, the mass effect of the growing tumour causes compression of the surrounding structures leading to intestinal obstruction, ureteric obstruction with hydronephrosis and vascular or neural compression; second, direct infiltration of the surrounding tissues can lead to perforation, ischaemia, fistulation and gastrointestinal or intratumorous bleeding.17 These effects lead to serious, and sometimes fatal outcomes.

Desmoid tumours are classified as intra-abdominal, extra-abdominal or in the abdominal wall.11 There is a strong correlation between desmoid-tumour development and patients with FAP: approximately 7.5% of desmoid tumours in the general population are associated with FAP and up to 32% of patients with FAP develop desmoid tumours. In the general population, desmoid tumours commonly involve extra-abdominal locations with only 5% being intra-abdominal. On the contrary, 80% of patients with FAP-associated desmoid tumours mostly present with intra-abdominal disease.11

Desmoid tumours are characterised histologically by proliferation of spindle-shaped cells and collagenous stroma.49 The morphological similarities among spindle-cell tumours poses the pathologist with several diagnostic possibilities. Of 320 desmoid tumour specimens studied by Goldstein et al, there was a 29% misclassification rate. The most common misclassified specimens were Gardner’s fibroma, scar tissue, superficial fibromatosis, nodular fasciitis, myofibroma and collagenous fibroma. Sarcomas can also be misinterpreted as desmoid-type fibromatosis.54 These tumours are benign but local recurrence is high because of the infiltrating nature of the tumour. Wang et al looked at 56 patients and reported an overall recurrence rate of 39.3%.55 Similarly, Ballo et al retrospectively reviewed 189 cases and found a 5-year and 10-year recurrence rate of 30% and 33%, respectively.56 Therefore, complete resection with negative surgical boundaries is crucial. Ballo et al describe a 10-year recurrence rate of 27% in patients with negative margins compared with a 54% recurrence rate in patients who were margin-positive.56 Achieving negative margins often necessitates resection of the surrounding tissues and sometimes results in operative trauma.57 Mastoraki et al and Nagata et al both report cases where tumours recurred years after resection of the initial tumour. In both instances, the tumours that recurred were unresectable due to adherence to surrounding organs.19 27 Rakha et al describe a case where the tumour that recurred was larger and more destructive than the first, requiring debridement and reconstruction of the abdominal wall.38

Since our patient had a benign tumour and the intervention in the first instance was to ‘wait and see’, the case was excluded from the standard cancer pathway targets. To reach a management decision, the case was discussed at our local MDT meeting. The MDT in the UK is comprised of medical and non-medical professionals who are responsible for the care of patients referred on the suspected/confirmed cancer pathway which is led by an MDT lead and supported by the Network leads. It includes clinicians from a variety of disciplines (radiologists, pathologists, surgeons, oncologists, specialist nurses, etc.) to discuss patient care and agree a treatment plan according to national guidelines. The MDT supports the delivery of cancer standards by reviewing performance in terms of achieving safe and timely care in line with good practice and cancer pathway standards. The MDT also takes responsibility for changing pathways as required and identified from audit, data collection, performance information and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance.58 Since desmoid tumours are rare, the follow-up varies across the literature. However, the UK guidance for the management of soft tissue sarcomas (including desmoid tumours) suggests that patients with low grade tumours should be followed up every 4–6 months for 3–5 years, then annually thereafter.59

Treatment for desmoid tumours has evolved in recent years especially for primary non-resectable locations. Local surgery is the first chosen treatment with en-bloc surgery no longer regarded as a key treatment option. For a patient who has been managed surgically, microscopic negative margins should be achieved if possible.60 There has been a shift to a more conservative approach, namely the ‘wait-and-see’ method, which is recommended as the first approach in Desmoid-type fibromatosis.11 This approach is justified as it has been well documented that desmoid tumours can be self-limiting where either growth arrest or spontaneous regression occur, most often if the tumour is primary.14 Radiotherapy can also be offered in conjunction with surgery if the clinician and patient decide that improved local control outweighs the risks associated with radiotherapy. Even when desmoid tumours are deemed resectable, systemic therapy alone or radiotherapy alone are also treatment options. The optimal dose of radiotherapy has not been defined. Reported doses range from 10 to 75 Gy for radiotherapy alone, and from 9 to 72 Gy for radiotherapy used as an adjuvant to surgery with increased complications rates reported with doses exceeding 56 Gy. A systematic review by Ghert et al describes manageable toxicities with imatinib and the combination of vinblastine and methotrexate for patients who are untreated or have failed surgery and/or radiotherapy. Other systemic options have been described in the literature: combinations of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (often sulindac); tamoxifen or doxorubicin with or without dacarbazine and dacarbazine alone. However, these latter options were used on small patient numbers and hence do not form part of an established guideline.60

Despite desmoid tumours being rare with limited guidance reported on specific diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, outcomes remain encouraging. In our literature search, only the case by Palladino et al described a fatal outcome where the patient underwent laparotomy and resection of a mesenteric mass and died from a myocardial infarction the following day.45 All other cases had positive operative outcomes and remained in remission on follow-up.

Patient’s perspective.

I would like to thank the medical staff involved with my care. Without this operation, I do not think I would have survived—it is a miracle that I am still alive. Thank you.

Learning points.

Desmoid tumours progress differently depending on factors such as anatomical site, hormonal influence and background disease such as familial adenomatous polyposis.

They can grow to very large sizes reaching up to 30 cm, often taking up majority of the abdominal cavity.

The complications caused by excessive tumour growth (bowel obstruction, perforation and organ compression) need to be managed on a case-by-case basis.

The literature is too limited to conclude that one specific treatment modality is optimal.

Desmoid tumour development needs to be monitored, and an individualised treatment plan established.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM led literature review supported by AA. Pathology assessment was provided by JC. HMK conducted clinical care of patient and supervised this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Jambhekar A, Robinson S, Zafarani P, et al. Intestinal obstruction caused by desmoid tumours: a review of the literature. JRSM Open 2018;9:205427041876334–4. 10.1177/2054270418763340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin D, Labgaa I, Petermann D, et al. Small bowel obstruction caused by a fast-growing desmoid tumor. Clin Case Rep 2020;8:2318–9. 10.1002/ccr3.3162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasseur A, Pasquer A, Feugier P, et al. Sporadic intra-abdominal desmoid tumor: a unusual presentation. J Surg Case Rep 2016;2016:rjw070–3. 10.1093/jscr/rjw070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Easter DW, Halasz NA. Recent trends in the management of desmoid tumors. summary of 19 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg 1989;210:765–9. 10.1097/00000658-198912000-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tchangai BK, Tchaou M, Alassani F, et al. Giant abdominopelvic desmoid tumour herniated Trough perineum: a case report. J Surg Case Rep 2021;2021:1–3. 10.1093/jscr/rjab295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park CG, Lee YN, Kim WY. Desmoid type fibromatosis of the distal pancreas: a case report. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2021;25:276–82. 10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.2.276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pop M, Bartos D, Anton O, et al. Desmoid tumor of the mesentery. Case report of a rare non-metastatic neoplasm. Med Pharm Rep 2021;94:256–9. 10.15386/mpr-1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitrovic Jovanovic M, Djuric-Stefanovic A, Velickovic D, et al. Aggressive fibromatosis of the right colon mimicking a gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a case report. J Int Med Res 2021;49:030006052199492–6. 10.1177/0300060521994927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omori S, Ito S, Kimura K, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid-type fibromatosis mimicking diverticulitis with abscess: a case report. In Vivo 2021;35:1151–5. 10.21873/invivo.12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurens JR, Frankel AJ, Smithers BM. Intra-Abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumour in a 56-year-old female: case report of a very rare presentation of an unusual tumour. Int J Surg Case Rep 2021;79:323–6. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin L, Tan Y, Su Z, et al. Gardner syndrome with giant abdominal desmoid tumor during pregnancy: a case report. BMC Surg 2020;20:282. 10.1186/s12893-020-00944-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande A, Tamhane A, Deshpande YS, et al. Ball in the wall: mesenteric Fibromatosis-a rare case report. Indian J Surg Oncol 2020;11:73–7. 10.1007/s13193-020-01070-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna K, Mofakham FA, Gandhi D, et al. Desmoid fibromatosis of the pancreas--A case report with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiol Case Rep 2020;15:2324–8. 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.08.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omi M, Kanao H, Aoki Y, et al. Minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic surgery for an intra-abdominal desmoid tumor: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2020;32:100560. 10.1016/j.gore.2020.100560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sierra-Davidson K, Anderson G, Tanabe K, et al. Desmoid tumor presenting 2 years after elective Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Case Rep 2020;2020:1–4. 10.1093/jscr/rjz379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahnashi Y, Alotaibi AS, Aldakhail M, et al. Desmoid tumor at the gastrointestinal anastomosis after a one-anastomosis gastric bypass (mini-gastric bypass): a case report. J Surg Case Rep 2020;2020:1–3. 10.1093/jscr/rjz411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asenov Y, Genadiev S, Timev A, et al. Ruptured desmoid tumor imitating acute appendicitis - a rare reason for an emergency surgery. BMC Surg 2019;19:194. 10.1186/s12893-019-0662-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebeling PA, Fun T, Beale K, et al. Primary desmoid tumor of the small bowel: a case report and literature review. Cureus 2019;11:1–6. 10.7759/cureus.4915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastoraki A, Schizas D, Vergadis C, et al. Recurrent aggressive mesenteric desmoid tumor successfully treated with sorafenib: a case report and literature review. World J Clin Oncol 2019;10:183–91. 10.5306/wjco.v10.i4.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stickar T, Berriel JAD, Polo JLM, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumor with an unusual origin in the intestinal wall: case report. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2018;31:1–2. 10.1590/0102-672020180001e1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akbulut S, Yilmaz M, Alan S, et al. Coexistence of duodenum derived aggressive fibromatosis and paraduodenal hydatid cyst: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2018;10:90–4. 10.4240/wjgs.v10.i8.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke E, Saeed M, Anant P, et al. Large intra-abdominal desmoid tumour posing diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, a case report. J Surg Case Rep 2018;2018. 10.1093/jscr/rjy304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K-C, Lee J, Kim BH, et al. Desmoid-Type fibromatosis mimicking cystic retroperitoneal mass: case report and literature review. BMC Med Imaging 2018;18:29. 10.1186/s12880-018-0265-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogawa T. Complete resection of a rectus abdominis muscle invaded by desmoid tumors and subsequent management with an abdominal binder: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2018;12:29. 10.1186/s13256-018-1575-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jafri SF, Obaisi O, Vergara GG, et al. Desmoid type fibromatosis: a case report with an unusual etiology. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017;9:385–9. 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Q, Wang K, Liu D, et al. Stomach desmoid tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10:10531–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagata T, Demizu Y, Okumura T, et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy for desmoid tumor of the abdominal wall: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14:245. 10.1186/s12957-016-1000-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugrue JJ, Cohen SB, Marshall RM, et al. Palliative resection of a giant mesenteric desmoid tumor. Ochsner J 2015;15:468–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bn A, Cd JK, Ps S, et al. Giant aggressive mesenteric fibromatosis- a case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:7–8. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11061.5594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D M, Ghalige HS, R S, et al. Mesenteric fibromatosis (desmoid tumour) - a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:1–2. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8520.5098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleetwood VA, Zielsdorf S, Eswaran S, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumor after liver transplantation: a case report. World J Transplant 2014;4:148–52. 10.5500/wjt.v4.i2.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monneur A, Chetaille B, Perrot D, et al. Dramatic and delayed response to Doxorubicin-dacarbazine chemotherapy of a giant desmoid tumor: case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol 2013;6:127–33. 10.1159/000349918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peled Z, Linder R, Gilshtein H, et al. Cecal fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) mimicking periappendicular abscess: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2012;5:511–4. 10.1159/000343045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basdanis G, Papadopoulos VN, Panidis S, et al. Desmoid tumor of mesentery in familial adenomatous polyposis: a case report. Tech Coloproctol 2010;14 Suppl 1:61–2. 10.1007/s10151-010-0613-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang C-W, Wang T-E, Chang W-H, et al. Unusual presentation of desmoid tumor in the small intestine: a case report. Med Oncol 2011;28:159–62. 10.1007/s12032-010-9429-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah M, Azam B. Case report of an intra-abdominal desmoid tumour presenting with bowel perforation. Mcgill J Med 2007;10:90–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka K, Yoshikawa R, Yanagi H, et al. Regression of sporadic intra-abdominal desmoid tumour following administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. World J Surg Oncol 2008;6:17. 10.1186/1477-7819-6-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rakha EA, Kandil MA, El-Santawe MG. Gigantic recurrent abdominal desmoid tumour: a case report. Hernia 2007;11:193–7. 10.1007/s10029-006-0165-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Disher AC, Biswas M, Miller TQ, et al. Atypical desmoid tumor of the abdomen: a case report. J Natl Med Assoc 1993;85:309–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Logio T, Rubin RJ, Aucoin E, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumor. Dis Colon Rectum 1980;23:423–5. 10.1007/BF02586794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JH, Ryu M-H, Park YS, et al. Intra-abdominal desmoid tumors mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumors - 8 cases: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:2010–8. 10.3748/wjg.v25.i16.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng C, Guo S, Kollie DEGB, et al. Ex vivo resection and intestinal autotransplantation for a large mesenteric desmoid tumor secondary to familial adenomatous polyposis: a case report and literature review. Medicine 2018;97:e10762–4. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim SH, Kim DJ, Kim W. Long-Term survival following port-site metastasectomy in a patient with laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a case report. J Gastric Cancer 2015;15:209–13. 10.5230/jgc.2015.15.3.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Efthimiopoulos GA, Chatzifotiou D, Drogouti M, et al. Primary asymptomatic desmoid tumor of the mesentery. Am J Case Rep 2015;16:160–3. 10.12659/AJCR.892521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palladino E, Nsenda J, Siboni R, et al. A giant mesenteric desmoid tumor revealed by acute pulmonary embolism due to compression of the inferior vena cava. Am J Case Rep 2014;15:374–7. 10.12659/AJCR.891044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galeotti F, Facci E, Bianchini E. Desmoid tumour involving the abdominal rectus muscle: report of a case. Hernia 2006;10:278–81. 10.1007/s10029-006-0075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Umemoto S, Makuuchi H, Amemiya T, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumors in familial polyposis coli: a case report of tumor regression by prednisolone therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1991;34:89–93. 10.1007/BF02050216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shayesteh S, Salimian KJ, Fouladi DF, et al. Pancreatic cystic desmoid tumor following metastatic colon cancer surgery: a case report. Radiol Case Rep 2020;15:2063–6. 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maemoto R, Miyakura Y, Tamaki S, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumor after laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a case report. Asian J Endosc Surg 2020;13:426–30. 10.1111/ases.12742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muneer M, Badran S, Zahid R, et al. Recurrent desmoid tumor with intra-abdominal extension after Abdominoplasty: a rare presentation. Am J Case Rep 2019;20:953–6. 10.12659/AJCR.916227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobayashi H, Sugihara K. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumor after resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the small intestine: case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014;44:982–5. 10.1093/jjco/hyu120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okamura A, Takahashi T, Saikawa Y, et al. Intra-Abdominal desmoid tumor mimicking gastric cancer recurrence: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:146. 10.1186/1477-7819-12-146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shih L-Y, Wei C-K, Lin C-W, et al. Postoperative retroperitoneal desmoid tumor mimics recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:6172–6. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldstein JA, Cates JMM. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol 2015;22:260–6. 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y-fei, Guo W, Sun K-kun, et al. Postoperative recurrence of desmoid tumors: clinical and pathological perspectives. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:26. 10.1186/s12957-015-0450-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pollack A, et al. Desmoid tumor: prognostic factors and outcome after surgery, radiation therapy, or combined surgery and radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:158–67. 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shinagare AB, Ramaiya NH, Jagannathan JP, et al. A to Z of desmoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:W1008–14. 10.2214/AJR.11.6657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NHS Trust . Cancer operational policy. NHS Trust name withheld, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dangoor A, Seddon B, Gerrand C, et al. Uk guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res 2016;6:1–26. 10.1186/s13569-016-0060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghert M, Yao X, Corbett T, et al. Treatment and follow-up strategies in desmoid tumours: a practice guideline. Curr Oncol 2014;21:642–9. 10.3747/co.21.2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]