Abstract

Gastroenteritis is one of the most common illnesses of humans, and many different viruses have been causally associated with this disease. Of those enteric viruses that have been established as etiologic agents of gastroenteritis, only the human caliciviruses cannot be cultivated in vitro. The cloning of Norwalk virus and subsequently of other human caliciviruses has led to the development of several new diagnostic assays. Antigen detection enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) using polyclonal hyperimmune animal sera and antibody detection EIAs using recombinant virus-like particles have supplanted the use of human-derived reagents, but the use of these assays has been restricted to research laboratories. Reverse transcription-PCR assays for the detection of human caliciviruses are more widely available, and these assays have been used to identify virus in clinical specimens as well as in food, water, and other environmental samples. The application of these newer assays has significantly increased the recognition of the importance of human caliciviruses as causes of sporadic and outbreak-associated gastroenteritis.

INTRODUCTION

Importance and Impact of Gastroenteritis

Acute gastroenteritis is one of the most common diseases of humans. In the United States, it is second only to acute viral respiratory disease as a cause of acute illness 61. Worldwide, more than 700 million cases of acute diarrheal disease are estimated to occur annually just in children under the age of 5 years 230. Gastroenteritis most commonly is manifested clinically as mild diarrhea, but more severe disease, ranging from upper gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea and vomiting) to profuse diarrhea leading to dehydration and death, may occur. The annual mortality associated with gastroenteritis has been estimated to be 3.5 to 5 million, with the majority of deaths occurring in developing countries 21, 97, 250.

Acute gastroenteritis is caused by a number of different agents, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Until recently, many cases were attributed to viruses because of the failure to identify a bacterial or parasitic pathogen. Although Reimann et al. 214 and Gordon et al. 77 suggested more than 50 years ago that viruses are a cause of diarrhea after inducing illness in volunteers with stool filtrates free of bacteria, it was only in 1972 that a virus (Norwalk virus) was definitively identified as a cause of acute gastroenteritis 139. Since that time, the number of viral agents associated with acute gastroenteritis has increased progressively.

Viral Causes of Gastroenteritis

Many different viruses have been found in the stools of persons with gastroenteritis. However, a causative role for each of these viruses has not been established. Criteria to define a virus as an etiologic agent of gastroenteritis include (i) identification of the virus more frequently in subjects with diarrhea than in controls, (ii) demonstration of an immune response to the specific agent, and (iii) demonstration that the beginning and end of the illness correspond to the onset and termination of virus shedding, respectively 148. Table 1 lists those viruses established as etiologic agents of gastroenteritis and other viruses found in stools that have not yet fulfilled the aforementioned criteria 9. Coronaviruses 34, 62, picobirnaviruses and picotrirnaviruses 35, 96, 174, pestiviruses 13, 257, and toroviruses 17, 18, 251 are candidate diarrheal agents because they are associated with diarrheal illness in animals and have been found in the stools of humans with gastroenteritis. However, these viruses have not fulfilled the criteria needed to establish them as diarrheal agents in humans 134, 148 and will not be considered further in this review. Non-group F adenoviruses and several enteroviruses (e.g., Coxsackie A and B viruses) are found in the stools of non-ill individuals with frequencies similar to those seen in ill individuals 148.

TABLE 1.

Causal relationship to diarrhea of enteric virusesa.

| Group | Viruses | Cultivation reportedb (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Causal relationship demonstrated | Rotaviruses | Yes 66 |

| Human caliciviruses | No | |

| Astroviruses | Yes 155, 156 | |

| Enteric (group F) adenoviruses | Yes 147 | |

| Candidate agents (etiologic relationship not yet determined) | Coronaviruses | Yes 215 |

| Echovirus type 22 | Yes 148 | |

| Picobirnaviruses, picotrirnaviruses | No 35, 96, 174 | |

| Pestiviruses | No 13, 257 | |

| Toroviruses | No 17, 18, 251 | |

| Other agentsc (causal relationship not demonstrated) | Non-group F adenoviruses | Yes 148 |

| Coxsackie A and B viruses | Yes 148 | |

| Echoviruses | Yes 148 |

Viruses are listed by relative clinical significance. Data are modified from R. L. Atmar and M. K. Estes, Clin. Microbiol. Newsl: 19:177–182, 1997 (9), with permission from Elsevier Science.

Virus cultivated from human enteric sample.

Present in stools of non-ill individuals with frequency similar to that seen in ill subjects.

Of the viruses that have been shown definitively to be causes of acute gastroenteritis, only the human caliciviruses cannot be grown in cell culture. The study of rotaviruses, enteric adenoviruses, and astroviruses has been facilitated greatly by the ability to propagate these viruses in cell culture. The ability to cultivate these viruses has allowed the production of reagents for use in diagnostic studies, a better understanding of factors correlated with immunity to infection, and the elucidation of each virus's life cycle. Although human caliciviruses have defied numerous attempts to propagate them in cell culture to date, recent developments in their study by using molecular biology techniques have increased our understanding of this group of viruses. This article will review the new diagnostic assays that have resulted from these advances.

HISTORY OF HUMAN CALICIVIRUSES

Recognition

In 1968, an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis (termed winter vomiting disease) occurred among students and teachers in a school in Norwalk, Ohio 1. The primary attack rate was 50%, with a secondary attack rate of 32%. Illness was characterized by nausea and vomiting in >90% and diarrhea in 38% of affected individuals, and the duration of illness was usually 12 to 24 h. Subsequently, organism-free filtrates of stools collected from affected individuals induced similar illness in human volunteers, and different treatments of the inoculum suggested that the causative agent was a small (<36 nm), ether-resistant (nonenveloped), relatively heat-stable virus 24, 57, 58. Attempts to propagate the agent in cell culture and organ culture were unsuccessful 24, 57.

In 1972, Kapikian et al. 139 used immune electron microscopy (IEM) to identify 27-nm viral particles, the Norwalk agent, in a fecal filtrate used to induce illness in human volunteers. Virus particles were precipitated in an antigen-antibody reaction using convalescent-phase serum from a volunteer who became ill following inoculation with the fecal filtrate. Antigen-antibody complexes were then visualized with an electron microscope. The assay was modified to quantify the amount of antibody in serum and demonstrated that significantly more antibody was present in convalescent-phase serum than in acute-phase serum. Because of these data, Norwalk virus (NV) was proposed to be the etiologic agent of the Norwalk, Ohio, outbreak of gastroenteritis 30. Later studies demonstrated that other small, round-structured viruses (SRSVs) morphologically similar to NV were associated with outbreaks of gastroenteritis 7, 59, 238, but NV remained the prototype of these fecal viruses.

Morphologically typical caliciviruses were first recognized in stool samples by Madeley and Cosgrove in 1976 176. These investigators found calicivirus particles in the fecal specimens of 10 children, but some of the children were asymptomatic, so that no conclusions as to the pathogenicity of the virus could be made. Later that year, Flewett and Davies 68 identified calicivirus particles in the small bowel from a fatal case of gastroenteritis, but because adenovirus particles also were present in large numbers, the significance of the calicivirus particles could not be determined. However, in the next several years, caliciviruses were definitively associated with several outbreaks of gastroenteritis 37, 38, 44, 45, 185 and became recognized as another virus group associated with gastroenteritis 33, 175.

Based on properties of NV and its appearance by electron microscopy, NV and other small round viruses were thought to be parvovirus-like 57, 137. However, in 1981 Greenberg et al. 93 published data suggesting that NV has a single structural protein with an estimated molecular mass of 59 kDa and proposed that Norwalk virus might be a calicivirus. Nine years later, Jiang et al. 216 provided molecular evidence that NV is a calicivirus by demonstrating that the viral genome consists of positive-sense, single-stranded, polyadenylated RNA. Subsequent elucidation of the complete sequence of NV and related SRSVs confirmed the genetic relatedness of these viruses to other caliciviruses 55, 108, 131, 153, 154, 225.

Classification

The classification of viruses responsible for acute gastroenteritis was first based on morphology (Table 2). For example, NV was the prototype of a group of agents initially called SRSVs. Recently, rapid advances in molecular biology allowed these viruses to be classified based on their genome characteristics, and most of the previously named SRSVs were shown to belong to the Caliciviridae.

TABLE 2.

Classification schemes for HuCVs

| Classification method | Groups |

|---|---|

| Morphologic | Small round viruses, SRSVs, “typical” caliciviruses |

| Antigenic | |

| IEM | IEM types, SPIEM types |

| Reactivity with VLP-specific immune sera | Antigenic groups |

| Cross-protection in experimental human infection | Antigenic types, possibly serotypes |

| Genetic (based on sequence information) | Genera (NLVs, SLVs), further divided into genogroups, further divided into genetic clusters |

Morphology.

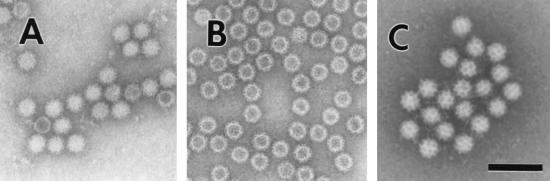

The virions are composed of a single major capsid protein. Structural analysis of virus particles from stool is limited by the small number of particles present in these samples. However, by negative-stain electron microscopy, the NV has an indistinct “feathery” outer edge and an indistinct surface substructure, although there is a suggestion of indentations on its surface (Fig. 1A). Expression of the capsid protein using the baculovirus system results in the self-assembly of the NV protein into virus-like particles (VLPs) (Fig. 1B). By negative-stain electron microscopy, these VLPs have a morphology similar to that of the native virus. The structure of these VLPs has been resolved by electron cryomicroscopy and computer image processing as well as by X-ray crystallographic methods 211, 212. The capsid exhibits a T = 3 icosahedral symmetry. The major structural protein folds into 90 dimers that form a shell domain from which arch-like capsomers protrude. A key characteristic of this architecture is 32 cup-shaped depressions at each of the icosahedral fivefold and threefold axes. These cup-like depressions are more prominent in some strains (particularly the Sapporo-like viruses [SLVs]), leading to the characteristic “Star of David” appearance from which caliciviruses get their name (Fig. lC). The name calicivirus is derived from the Latin calyx, meaning cup or goblet, and refers to the cup-shaped depressions visible by electron microscopy.

FIG. 1.

Electron micrographs of (A) NV, (B) baculovirus-expressed NVL particles, and (C) Sapporo virus. Bar, 100 nm.

Genomic organization and classification.

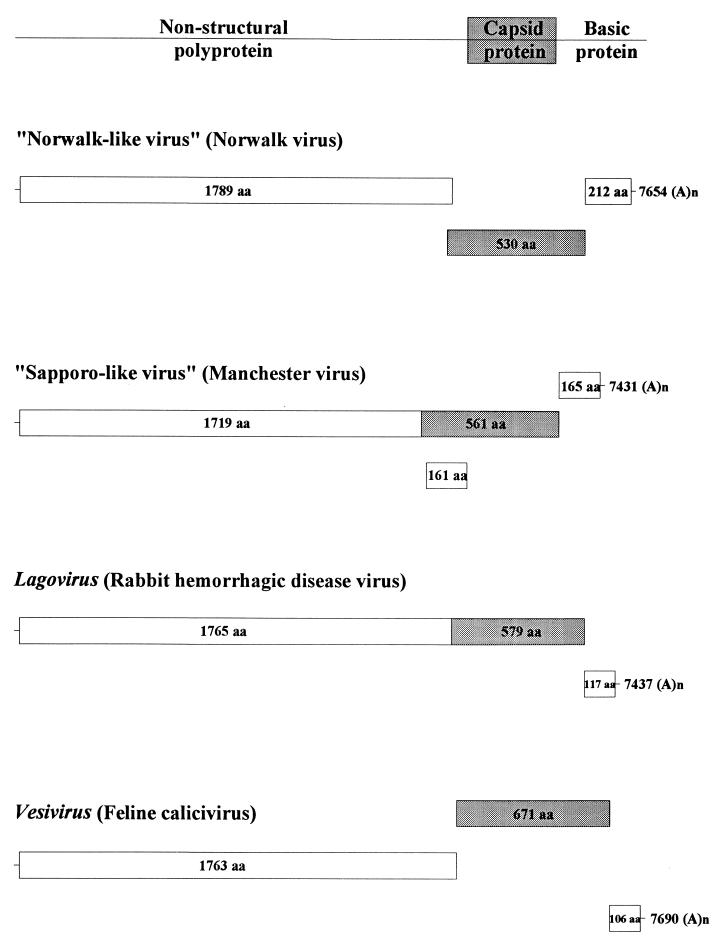

In 1990, the genome of NV was cloned and characterized 124. More recent studies have characterized and completely sequenced this and other human viruses in the family 55, 108, 131, 153, 154, 170, 171, 225. Recently, the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses established and approved four genera within the family Caliciviridae, including two human calicivirus (HuCV) genera 86. These nonenveloped viruses have a diameter of 27 to 40 nm by negative-stain electron microscopy and a buoyant density of 1.33 to 1.41 g/cm3, and they contain a positive-sense polyadenylated single-stranded RNA of approximately 7.6 kb (Fig. 2). The two HuCV genera currently have the tentative names of “Norwalk-like viruses” (NLVs; type strain, NV [Hu/NLV/Norwalk virus/8FIIa/1968/US]) and the “Sapporo-like viruses” (SLVs; type strain Sapporo virus [Hu/SLV/Sapporo virus/1982/JA]). The proposed nomenclature for HuCVs is species infected/virus genus/virus name/strain designation/year of isolation/country of isolation. Table 3 shows the strain name and proper name for common NLV and SLV strains and for the strains discussed in this review. Common names will be used for the human virus strains throughout the rest of the review.

FIG. 2.

Schematic of the genomic organization of viruses from the four different genera of the Caliciviridae. Strains [GenBank numbers] for which the entire genomic sequence is available are presented for each of the genera: NV [M87661] 108, 131, Manchester virus [X86560] 170, 171, rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus [M67473] 187, and feline calicivirus [M86379] 31. A nonstructural polyprotein (aa 1719 to 1789) is encoded by the 5′ end of the genome. The major capsid protein (shaded area) is in frame for the SLVs and lagoviruses, while it is in the +1 frame for NLVs and −1 frame for the vesiviruses. A basic protein is encoded at the 3′ end of the genome for all four genera. SLVs have another ORF (+1) overlapping the capsid ORF that is not seen in the other genera.

TABLE 3.

Representative strains in the two HuCV generaa

| Genus and genogroup | Virus common name (strain designation) | Clustera |

|---|---|---|

| NLVs | ||

| Genogroup I | Norwalk virus (Hu/NLV/NV/8fIIa/1968/US) | NV |

| Southampton virus (Hu/NLV/SV/1991/UK) | SV | |

| Desert Shield virus (Hu/NLV/DSV395/1990/SR) | DSV | |

| Cruise ship virus (Hu/NLV/184–01388/1990/US) | CSV | |

| Genogroup II | Snow Mountain agent (Hu/NLV/SMA/1976/US) | SMA |

| Hawaii virus (Hu/NLV/HV/1971/US) | HV | |

| Mexico virus (Hu/NLV/MX/1989/MX) | TV | |

| Toronto virus (Hu/NLV/TV/TV24/1991/CN) | TV | |

| Lordsdale virus (Hu/NLV/LV/1993/UK) | LV | |

| Grimsby virus (Hu/NLV/GRV/1995/UK) | LV | |

| Gwynedd virus (Hu/NLV/GV/1993/UK) | GV | |

| White River virus (Hu/NLV/WRV/290-12275/ 1994/US) | WRV | |

| SLVs | Sapporo virus (Hu/SLV/Sa/1982/JA) | Sa |

| Manchester virus (Hu/SLV/Man/1993/UK) | Sa | |

| Parkville virus (Hu/SLV/Park/1994/US) | PV | |

| London virus (Hu/SLV/Lond/29845/1992/UK) | LoV |

Calicivirus strains that infect animals (bovine and swine) and have characteristics that place them in the NLV and SLV genera have also been described 51, 100, 172, 233. In contrast, the other two genera within the family Caliciviridae (Lagovirus [type strain, rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus, Ra/LV/RHDV/V351/1987/CK] and Vesivirus [type strain, swine vesicular exanthema virus, Sw/VV/VESV/A48/1948/US]) are currently recognized to contain strains that naturally only infect animals (and not humans). There is a single case report of infection of a person who was isolating a vesivirus in the laboratory 229.

The genome of NLVs is organized in three major open reading frames (ORFs). For NV, the first ORF at the 5′ end encodes a large polyprotein of 1738 amino acids (aa) with a predicted molecular weight of 193.5 (193.5K). This polyprotein contains short motifs of similarity with the 2C (helicase), 3C (cysteine protease), and 3D (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) proteins of picornaviruses. Thus, the 5′ end of the genome of the NLVs codes for a precursor of the nonstructural proteins. ORF2 encodes a 530-aa (56.6K) protein, the capsid protein. The ORF2 protein expressed in insect cells self-assembles into VLPs as explained below (Fig. 1B). ORF3 at the 3′ end of the genome is predicted to code for a small protein of 212 aa (22.5K) with a very basic charge (isoelectric point of 10.99). The ORF3 protein does not have sequence similarity with any other proteins in the GenBank database, and its function remains unknown. Recent studies indicate that the ORF3 protein is a minor structural protein, based on its being found in VLPs expressed from cDNA constructs that contain both ORF2 and ORF3 and in virus particles purified from stool 75.

The genome of SLVs is organized slightly differently. For Manchester virus, the first ORF codes for the nonstructural proteins as well as the capsid protein, which is found in-frame at the end of the nonstructural proteins 170, 171. This genome organization is similar to that found in the animal calicivirus rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus belonging to the genus Lagovirus (Fig. 2) 187. ORF2 encodes a predicted small, highly basic protein of unknown function, similar to ORF3 for NV. Manchester virus contains a third ORF within the capsid protein that could encode another small basic protein. The significance of this ORF is unclear, as this ORF is not seen in any of the other calicivirus genomes sequenced thus far, and the small protein it potentially encodes shows no sequence homology to other viral proteins in the database 171.

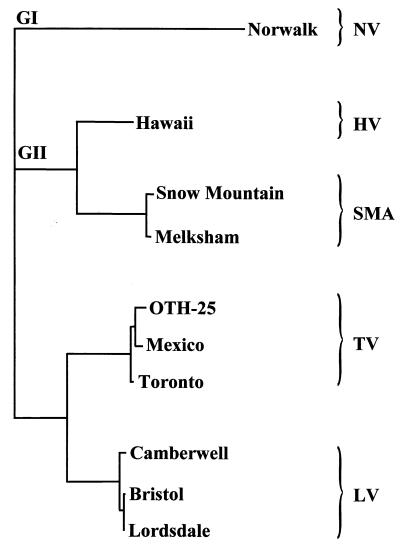

Sequence information has also been used to identify relationships between strains of NLVs and SLVs. Most comparisons have focused on the region of the genome encoding the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase or on the capsid protein gene 3, 5, 20, 43, 67, 109, 127, 161, 179, 180, 182, 197, 208, 243, 246, 255, 256, but comparisons of other genomic regions have also been made. Such comparisons have allowed the further subdivision of viruses in the NLV genus into two genogroups (Table 3) and viruses in both HuCV genera into clusters 6, 67, 122, 195, 196, 245 (Fig. 3). Table 3 identifies the genogroup and proposed genetic cluster for several reference strains. Figure 3 shows an unrooted phylogenetic tree of genogroup II viruses for which the entire sequence of the capsid gene is available, using the NV (genogroup I) capsid gene sequence as an outgroup. In most studies using the newly developed assays described below, these additional subdivisions have correlated with reactivity in the diagnostic assays, and they have been useful in evaluating virus transmission in molecular epidemiology studies 28, 50, 195, 245.

FIG. 3.

Unrooted phylogram generated using the entire capsid amino acid sequence of nine genogroup II (GII) strains and one genogroup I (NV) strain and the PAUP program in the Genetics Computer Group suite of programs 73. Strains within different genogroup II genetic clusters are indicated, with the genogroup I strain NV serving as an outgroup. GenBank accession numbers used for this analysis are as follows: NV, M87661; HV, U07611; SMA, U75682; Melksham virus, X81879; Oth-25, L23830; MX, U22498; TV, U02030; Camberwell virus, U46500; Bristol virus, X76716; and LV, X86557.

Cross-protection and serologic studies. Early volunteer studies examined the ability of different viruses to induce cross-protection. Based on these studies in addition to IEM, NV, Hawaii virus (HV), and Snow Mountain agent were defined as separate serotypes. Four distinct serotypes of the NLVs (NV, HV, SMA, and Hu/NLV/Taunton agent/1979/UK) and one serotype of the SLVs (Sapporo) were originally described by serologic IEM studies employing virus particles shed in stools as the antigen and paired sera from infected individuals as the source of antibody 133. Additional antigenic groups were proposed subsequently 165, 202. These serotype designations assumed that antibody reactivity by IEM reflects the reactivity of neutralizing antibodies. This may not be the case, and clear definition of serotypes remains difficult to achieve due to the lack of a cultivation system. More recently, the antigenic relationships between a subset of these viruses have been examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbentassay (ELISA) using hyperimmune antisera raised against VLPs. By this method, Norwalk, Mexico, and Grimsby viruses are antigenically distinct 102, as are NV and Desert Shield virus 161, NV and HV 87, and NV and Sapporo viruses 198.

FIRST-GENERATION DIAGNOSTIC TESTS USING HUMAN REAGENTS

During the 1970s and 1980s, tests for the diagnosis of NV infections were designed using reagents from previously infected humans. The number of virus particles in the stools of infected subjects is sufficiently small that hyperimmune sera could not be produced in animals. (An exception was the use of partially purified Sapporo virus to produce hyperimmune sera in guinea pigs [192].) The inability to propagate NV and related viruses in cell culture also prevented the production of animal hyperimmune sera. Thus, stools of acutely infected individuals served as a source of virus antigen, and convalescent-phase sera from infected individuals were used as hyperimmune sera. These restrictions limited the general availability of these diagnostic tools to only a few research laboratories 40. However, a number of tests were developed with these reagents and used to begin to define the epidemiology of NV and other human caliciviruses.

Electron Microscopy

Direct electron microscopy.

Detection of enteric viruses in stool specimens using direct electron microscopy requires virus concentrations of at least 106 per ml of stool 56. In many laboratories, stool is mixed with phosphate-buffered saline or tissue culture medium to form a 10 to 20% suspension before being clarified by low-speed centrifugation. Subsequent concentration of virus may be achieved by ultracentrifugation or precipitation with ammonium sulfate. Virus particles are negatively stained using one of a number of available electron-dense stains, including phosphotungstic acid, uranyl acetate, and ammonium molybdate 56. Viral particles must be distinguished from nonviral material, and this can be particularly difficult for the NLVs that do not have typical calicivirus morphology 56, 140. The small numbers of viral particles present in fecal samples make direct electron microscopy, even after concentration, relatively insensitive. Nevertheless, direct electron microscopy is used to screen fecal specimens for enteric viruses in the public health laboratories of many countries, and it is clear that talented electron microscopists who receive fecal samples collected early in the course of an infection can often detect viruses 52, 179, 246, 256. However, this method requires highly skilled microscopists and expensive equipment, making it not feasible for large epidemiological or clinical studies.

IEM .

The use of immune serum to aid in virus identification was first described for tobacco mosaic virus in 1941 2. This method had been used for only a few human viruses 22, 49, 135 before Kapikian et al. 139 adapted it for the detection of NV in stool filtrates. Since then, it has been used to identify many other SRSVs in stool samples 27, 59, 141, 238, 242. A clarified stool suspension is incubated with a reference serum or saline (as a control) for 1 h at 37°C, and immune complexes are pelleted by ultracentrifugation 140. The pellet is suspended in a few drops of distilled water and negatively stained as for direct electron microscopy. The saline control is necessary to demonstrate the specificity of the immune serum because virus clumping may occur in the absence of antibody 56, 194. A positive sample has aggregates of viral particles which are absent in the saline control sample. Although IEM was first used to detect NV, it is positive on stool samples from only approximately half of volunteers who become ill following artificial challenge with NV 237. When IEM has been applied to outbreaks of gastroenteritis associated serologically with NV infection, it has been positive in only about 20% of the outbreaks, and just over one third of stool samples from affected individuals in these outbreaks are IEM positive 141. The lack of detection probably reflects the very low concentration of virus in many stool samples and the lack of collection of the first early diarrheal stool samples.

Modifications to the IEM method have been made to improve the ease with which viral particles are detected and to simplify the performance of the test. Solid-phase IEM (SPIEM) has been used to capture viral particles directly onto the grid 56, 164, 168. Virus-specific immunoglobulin or broad-spectrum immunoglobulin (gamma globulin) is used to coat the grids, and virus particles from a fecal suspension are then captured by interaction with antiviral antibodies. Protein A has been used to capture the antibody onto the grid before exposure to fecal suspensions; this may increase the exposure of antigen-binding sites by capturing the antibodies through their Fc receptor 56, 149, 165. SPIEM has been used as a tool for “serotyping” HuCVs 165, 166. Another modification of IEM has been the use of colloidal gold-protein A conjugates to label in suspension clumps of virus and antibody; this modification allows specific antigen-antibody interactions to be distinguished from nonspecific clumping 149.

IEM has also been used to detect seroresponses to viral antigen 37, 59, 139, 202. In this assay, the source of viral antigen is a stool filtrate in which viral particles are easily detected by electron microscopy or a stool from which virus has been partially purified. Antigen is mixed with a 1:5 dilution of the serum to be tested, and the mixture is examined. The amount of antibody is determined by the appearance of the viral particles and is rated 0 to 4+, with 0 being no viral aggregates noted and 4+ being nonglistening, heavily coated viral aggregates 139. This assay is type specific and has been used to evaluate the association of HuCVs with outbreaks of gastroenteritis 37, 56, 59, 202. While IEM is an important component of the diagnostic armamentarium for the noncultivatable caliciviruses, like direct electron microscopy, the application of IEM is limited and not readily applied to large epidemiological studies.

Immune Adherence Hemagglutination Assay

IEM was found to be a specific and reproducible method for antibody determination, but it is laborious, cumbersome, and time-consuming to perform. The immune adherence hemagglutmation assay (IAHA) was developed to allow the evaluation of Norwalk antibody levels in greater numbers of sera so that epidemiological studies of seroprevalence could be performed 138. Viral particles are purified from stool and used as antigen, and antigen-antibody-complement interactions are detected in a microtiter plate format by agglutination of sensitive human O erythrocytes. Kapikian et al. used the IAHA to demonstrate seroprevalence rates ranging from <20% in children to approximately 50% in adults in the fifth and sixth decades of life 91, 138. Although the assay has the advantage of requiring less antigen for its performance than complement fixation antibody assays, it was soon replaced with another assay, the blocking radioimmunoassay (RIA), which uses even less antigen and is more sensitive 91, 94, 136. IAHA also could not be adapted to detect viral antigen in stool specimens.

Radioimmunoassay

RIA was developed as an alternative to IEM for the detection of NV antigen in stool 91, 94. The assay is used in a microtiter format, and it detects both particulate and soluble antigen 133. Preinfection and convalescent sera from a volunteer experimentally infected with NV and known to have a high-titered antibody response (by IEM and IAHA) are used to capture virus antigen in duplicate wells. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) purified from a convalescent serum of a NV-infected chimpanzee or human volunteer and radiolabeled with 125I is used as a detector system. The use of preinfection (negative) and convalescent (positive) serum differentially captures NV antigen and is indicated by greater radioactivity (counts per minute) in the convalescent than in the preinfection sample. Positive-negative (P/N) ratios greater than or equal to 2 indicate the presence of virus antigen in the sample 94. RIAs for the SMA and the morphologically typical HuCV were developed later 60, 191. In the latter assay, pre- and postvaccination sera from guinea pigs hyperimmunized with purified virus are used in place of human-derived reagents 191. For optimal specificity, positive samples must be confirmed using a blocking assay. Convalescent serum from a calicivirus-infected individual is incubated with captured virus antigen prior to addition of the radiolabeled IgG; a reduction in bound radioactivity of 50% or more indicates specific capture of virus antigen in samples with a P/N ratio of 2 or more 191. The RIAs using human-derived reagents do not require a blocking assay for confirmation of positive samples. All of these assays are specific (i.e., do not detect unrelated HuCVs or other enteric viruses) and 10- to 100-fold more sensitive than IEM 60, 94, 191. However, RIAs are negative when applied to stool samples from as many as one third of symptomatic volunteers experimentally infected with NV 231.

RIAs have been modified to detect virus-specific antibodies using a blocking format similar to that described above. A convalescent-phase serum from an HuCV-infected subject is used to capture partially purified virus antigen. Serial twofold dilutions of the serum to be tested for antibody determination are added next, and after an overnight incubation, 125I-labeled, virus-specific IgG is added. If virus-specific antibodies are present in the serum being tested, binding of the radiolabeled IgG is blocked. A reduction in bound radioactivity of 50% or greater is used to define the presence of virus-specific antibodies, and the reciprocal of the last dilution at which 50% or greater blocking occurs is the titer of virus-specific antibody 94. RIA blocking assays have been developed for the detection of antibody to NLVs (NV and SMA and SLVs 60, 91, 94, 191. The RIA blocking assay for NV-specific antibody is 10 to >200 times more sensitive than the IAHA 91, 94.

RIA antigen and antibody detection assays were used to further characterize infection and illness in experimentally induced human infection 23, 48, 231, to perform seroprevalence studies in different populations 47, and to investigate outbreaks of gastroenteritis 14, 15, 46, 76, 92, 95, 98, 99, 141–144, 151, 169, 235, 253. The application of these assays helped identify NV and related viruses as a common cause of nonbacterial gastroenteritis outbreaks. For example, a review of 74 outbreaks of gastroenteritis investigated by the Centers for Disease Control between 1976 and 1980 showed that 42% of the outbreaks were associated with NLVs and an additional 23% were possibly associated with NLVs 141.

Enzyme Immunoassay

As the technology to perform immunoassays using nonisotopic reporters developed, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) utilizing the same principles as the RIAs described above were developed for the detection of NV infection. Partially purified IgG is labeled with biotin or horseradish peroxidase in place of 125I. The antigen detection EIAs detect NV in stool samples with a frequency similar to that seen with RIAs 72, 115, 178. Blocking EIAs for the detection of serum antibody are approximately twofold more sensitive than the comparable blocking RIA, although both assays detect fourfold or greater rises in serum antibody with similar frequency. An advantage of EIAs over RIAs is the increased stability of the reagents used to perform the tests. 125I-labeled anti-NV IgG has a much shorter shelf life (several days to 2 weeks) than does anti-NV IgG labeled with biotin (3 months or more at −20°C) or horseradish peroxidase (6 months at 4°C) 72, 115. Other advantages of the EIA include the elimination of the use of radioisotopes and the decreased time needed to perform the blocking EIA compared to the blocking RIA (3 days and 6 days, respectively) 72.

EIAs for the detection of SMA and HV were developed later 178, 241, as were EIAs for the detection of IgM and IgA serum antibody responses 64, 65. The EIAs were applied in a fashion similar to RIAs, being used on specimens from experimental human infection studies 71, 177 and from outbreak investigations 16, 29, 114, 117, 249.

Western Blot Assay

Another approach used for the evaluation of antibody responses has been the Western blot assay. For this assay, virus was partially purified from stool for use as an antigen 112. Multiple bands appeared on blots used to assay human serum specimens, but when acute- and convalescent-phase sera were tested, increasing reactivity with a protein of approximately 63 kDa was identified. The specificity of this reactivity was confirmed using virus purified by isopycnic cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation 112. In some assays convalescent sera also showed increasing reactivity with a second band with an approximate molecular size of 33 kDa 201, which may represent the soluble protein identified following proteolytic cleavage of the capsid protein 111. When applied to clinical specimens from outbreaks of gastroenteritis, the Western blot assay gave results comparable to those obtained using IEM, although antibody detected by Western blot persisted for a longer period of time than did that detected by IEM 112, 145. The Western blot assay may detect a larger number of epitopes than IEM because it is able to detect antibody to related viruses that is not recognized by IEM 112. While this assay has theoretical advantages for the confirmation of HuCV infections, it has not been used by many laboratories, probably because of high background reactivities and lack of a reproducible source of viral antigen.

DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION OF NEWER DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The successful cloning of NV led to the development of new reagents and methods for the diagnosis of infections caused by HuCVs. When the NV capsid protein was expressed in a baculovirus expression system, VLPs were generated 130. These VLPs were subsequently shown to be morphologically and antigenically similar to native virus particles 88. The VLPs were used to immunize different animal species to produce polyclonal and monoclonal immune sera that could then be used to establish EIA-based diagnostic assays. Virus sequence was used to design primer pairs for the detection of HuCVs using reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. The development and application of these newer assays are described below.

Antigen Detection

EIA with hyperimmune animal sera.

The production of NV VLPs provided sufficient quantities of viral capsid antigen to allow the generation of hyperimmune sera in mice, guinea pigs, and rabbits 130. Hyperimmune sera from these animals have NV-specific antibody titers of 1:256,000 to >1:1,000,000. Subsequently, VLPs have been produced for other HuCVs, including Mexico virus (MX), SMA, HV, Desert Shield virus, Toronto virus (TV), Grimsby virus (GRV), Sapporo virus, Southampton virus, and Lordsdale virus (LV) 55, 87, 102, 109, 126, 160, 161, 198. Polyclonal hyperimmune animal sera produced by immunization of different animal species with VLPs have been used to develop antigen detection EIAs for use in clinical specimens 102, 121, 128. These immune sera have been quite specific, detecting homologous recombinant VLPs in an EIA format but not reacting with heterologous VLPs.

The antigen detection EIA utilizing polyclonal animal hyperimmune sera is set up in a sandwich format 79, 121. Rabbit hyperimmune serum is used for capture of viral antigen, and guinea pig hyperimmune serum is used to detect the captured antigen. The presence or absence of guinea pig serum is determined using a goat anti-guinea pig serum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. EIAs using hyperimmune sera generated from recombinant NV or recombinant MX (rMX) VLPs detect similar amounts of antigen, identifying an estimated 105 to 106 VLP particles per well 79, 121. These antigen detection assays were found to detect native virus in stool samples with a sensitivity comparable to that of RT-PCR. The NV antigen detection assay was found to be more sensitive than RIA 79, 199. Of 50 EIA-positive stool samples obtained from experimental human infection studies, only 24 samples were positive by RIA; the 26 RIA-negative samples were shown to contain virus by RT-PCR. In contrast to the results of IEM studies in which viral shedding could not be documented 100 h following experimental human challenge, the antigen detection EIA identified NV in stool for up to 13 days 203, 237. Thus, the antigen detection EIA using hyperimmune sera raised against VLPs is more sensitive than earlier assays that relied on human reagents 88. The specificity of the assays for HuCVs has been shown by the lack of reactivity with other enteric viruses, including rotaviruses, adenoviruses, astroviruses, hepatitis A virus, and enteroviruses 79, 121, 199.

A limitation of these antigen detection assays was recognized when the assays were applied to clinical samples containing other HuCVs. For example, the antigen detection assay that utilizes hyperimmune sera raised to rNV VLPs only detects a subset of genogroup I NLVs and does not detect genogroup II NLVs 128, 161. Only the most closely related viruses in genogroup I (≥90% aa identity in the polymerase region) were detected in this assay. Similarly, the antigen detection assay that utilizes hyperimmune sera raised to rMX VLPs is most efficient at detecting genogroup II NLVs that are the most closely related to MX and does not detect genogroup I viruses and 104, 121. For example, an assay using hyperimmune sera raised to rMX VLPs does not detect the genogroup II NLV GRV in stool samples, and conversely, an assay using hyperimmune serum raised against rGRV VLPs does not detect MX in stool 102. These assays also do not detect SLVs. Thus, the lack of an EIA that is broadly reactive with a range of HuCVs has limited the utility of these assays. When applied to specimens in epidemiological studies (Table 4), positive stool samples have been identified infrequently with these assays in most studies 43, 118, 127, 193, 199, 213, 228, 254. In a few reports of outbreaks, antigen detection EIAs have been positive in more than 20% of samples tested 146, 167. When multiple assays have been used, results have been better, but it remains unclear how many individual assays will be needed to ensure the detection of most human caliciviruses. No EIAs using polyclonal sera are available yet commercially.

TABLE 4.

Detection of HuCVs in stool specimens with antigen detection EIAs that use rVLPs as the antigen source for polyclonal hyperimmune antibody production

| Study type and location | Infecting virus strain | VLP antigen | No. positive/no. of samples tested (% positive) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental human infection | ||||

| U.S. | NV | rNV | 35/41 (85) | 79 |

| rMX | 0/8 (0) | 121 | ||

| rGRV | 0/5 (0) | 102 | ||

| U.S. | SMA | rNV | 0/8 (0) | 121 |

| rMX | 2/8 (25) | |||

| U.S. | HV | rNV | 0/8 (0) | 121 |

| rMX | 1/8 (13) | |||

| Epidemiologic studies of sporadic cases of gastroenteritis | ||||

| Kenya | rNV | 1/1,186 (<0.1) | 193 | |

| rMX | 0/286 (0) | |||

| India | rGRV | 7/80 (8.8) | 132 | |

| Japan/Southeast Asia | rNV | 1/159 (0.6) | 199 | |

| rNV | 2/155 (1.3) | 118 | ||

| rMX | 1/155 (0.6) | |||

| Mexico | rNV | 0/54 (0) | 127 | |

| South Africa | rNV | 0/1296 (0) | 254 | |

| rMX | 9/1296 (0.7) | |||

| rNV | 5/276 (1.8) | 228 | ||

| rMX | 12/275 (4.3) | |||

| U.K. | rNV | 0/187 (0) | 43 | |

| rNV | 0/260 (0) | 42 | ||

| rMX | 1/260 (0.5) | |||

| Venezuela | rNV | 4/1120 (0.4) | 213 | |

| Epidemiologic studies of outbreaks of gastroenteritis | ||||

| Japan/Southeast Asia | rNV | 2/42 (4.8) | 118 | |

| rMX | 3/42 (7.1) | |||

| South Africa | rNV | 1/3 (33) | 255 | |

| rMX | 0/3 (0) | |||

| U.K. | rMX | 25/109 (23) | 167 | |

| rNV | 0/unstated (0) | 42 | ||

| rMX | 15/192 (8) | |||

| U.S. | rNV | 5/19 (26) | 146 |

EIA with MAbs.

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have been prepared using native NV, native SMA, and rNV VLPs 110, 113, 239. Similar to what was seen with polyclonal sera, these MAbs are often type specific, recognizing the capsid protein of the immunizing virus but not that of other NLVs. The MAbs have been evaluated in limited studies for the detection of virus in stool samples. One assay format used a pool of two MAbs for antigen capture and also antigen detection. The detector antibodies were conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. This assay was reported to have a twofold greater sensitivity (as measured by the amount of virus detected) than assays using polyclonal sera, detected NV in 15 of 15 stool samples from subjects infected with NV, and failed to detect HV in any of nine stool samples from infected subjects 113.

In a separate study, a panel of 10 different MAbs were used for antigen capture, and antigen detection was performed using guinea pig anti-NV polyclonal antisera and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig immunoglobulin. All 10 MAbs tested in this study were able to capture NV 110. Subsequently, these MAbs were used in competition EIAs to map epitopes recognized on the capsid of rNV VLPs 107. Six to eight different epitopes covering five nonoverlapping regions of the capsid protein were identified. Three of the MAbs (NV3901, NV3912, and NV2461) recognized a single epitope and also captured Chiba virus VLPs, derived from a genogroup I virus with 75% amino acid identity to NV over the entire capsid. When NV3901 was used as the capture antibody in an antigen detection EIA with a polyclonal detector antibody, genogroup I viruses were detected in 9 of 15 fecal (RT-PCR positive) specimens, with positives representing four of five genogroup I genetic clusters (based on capsid sequence) assayed. The amino acid identities of the genogroup I viruses ranged from 63 to 70% over the entire capsid sequence compared to NV. The one genetic cluster not detected by the EIA had the lowest (63%) amino acid identity to NV 107. This is the first report of cross-reactive epitopes on NLVs. The failure to detect virus in all specimens by antigen EIA was thought to be due to differences in virus concentration in the samples tested, with RT-PCR having greater sensitivity than the antigen detection EIA, or to genetic variation among the genogroup I NLV genetic clusters 107. The description of a common epitope for genogroup I viruses leaves open the possibility that a similar common epitope may be present in genogroup II viruses. If all NLVs contain one or a limited number of common epitopes, the development of a broadly reactive antigen detection EIA will be possible. Such assays are desirable because large numbers of samples could be tested in a rapid and cost-effective manner. Alternatively, the genogroup I EIA may be combined with one or more less broadly reactive genogroup II EIAs to detect virus in stool samples. Such an approach, using an rGRV EIA for genogroup II viruses, compared favorably with results obtained by RT-PCR in an evaluation of specimens collected in southern India 132.

Antibody Detection

EIA with VLPs. The production of VLPs for NV and other NLVs has allowed the detection of immune responses to infection with these viruses. In these assays, VLPs are used to coat 96-well microtiter plates, and after blocking and washing steps, serial dilutions of human serum are added. Antibodies reacting with the VLPs are detected with goat anti-human immunoglobulin conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., horseradish peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase). The assay can detect total or class- or subclass-specific serum antibodies, depending on the reagents used to detect the bound human antibody 80, 116, 130, 240. The assay also has been modified to detect NV-specific IgA in fecal samples 203.

Two different approaches have been used to determine the amount of virus-specific antibodies in a serum specimen. The approach used by most laboratories is to perform a serial dilution of the serum specimen and to determine the last dilution that gives a reading above an empirically determined cutoff value 28, 41, 105, 116, 163. A second approach is to measure the amount of signal (e.g., optical density) from a single dilution of serum and to relate the measured signal to that measured using a standard reference serum 127, 189, 195, 207. Advantages of the latter method are that it allows a larger number of sera to be tested and is simpler and less expensive to perform. However, practical and theoretical problems limit the utility of testing a single dilution of serum. The practical problem is that well-characterized standard sera to be used as a reference reagent are not generally available, so that most laboratories cannot set up these assays. The theoretical problem is that the measurement of signal at a single dilution is affected by many factors besides the amount of antibody present in the sample, including the affinity of antibody in the sample for the test antigen and variability in the serum constituents that can affect antigen-antibody interactions. Thus, although antibody determinations using a single dilution of serum have been used in both seroprevalence studies 127, 207 and other epidemiological studies 195, most laboratories quantify virus-specific antibodies in serum using endpoint titration 28, 41, 105, 116, 163.

The VLP-based antibody detection EIA is more sensitive than assays using human reagents in RIA-, blocking EIA-, or IEM-based formats 88, 189. Total anti-NV antibody levels are 1.25- to >40-fold higher using an rNV VLP EIA assay than those obtained using RIA or blocking EIA. When applied to sera from experimental human or chimpanzee infection and from outbreaks of gastroenteritis, the rNV VLP EIA detects fourfold or greater increases in serum antibody levels more frequently than IEM and at least as frequently as RIA and blocking EIA 88, 189. The antibody rNV VLP EIA identified infection following experimental human challenge better than the antigen detection EIA, detecting 40 of 41 (98%) infections compared to 36 of 41 (88%) infections 79. Assays utilizing other VLPs, including rMX, rTV, rHV, rSouthampton virus, and rLV, have also been developed 127, 195, 206.

The antibody detection EIA has been used to characterize IgG, IgM, and IgA serologic responses following experimental human infection with NV 80. Eight of 13 infected subjects had fourfold or greater increases in virus-specific antibody levels between 8 and 11 days following infection; ill subjects (eight of nine) were more likely to have these early responses, while antibody rises were seen in asymptomatic subjects only after 15 days. All infected subjects (n = 14) developed virus-specific IgM serum antibody. Virus-specific IgM serum antibody was present as early as 9 days following infection, but it did not develop in some subjects until 2 weeks after infection. IgM serum antibody could still be detected 3 months later in some subjects. Fourfold or greater increases in virus-specific IgA serum antibody were detected in all nine symptomatic infections but in only two of five asymptomatic infections. Virus-specific geometric mean serum antibody levels of infected and uninfected subjects were similar 3 months after challenge 80. The kinetics of the IgM and IgA responses are similar to those seen in earlier studies using human reagents 64, 65. The presence of neither virus-specific serum IgG, IgM, or IgA nor of fecal IgA is associated with protection from infection 80, 203, 240. Low serum antibody levels appear to be associated with a decreased likelihood of infection following experimental human challenge and natural exposure 79, 226.

Virus-specific IgM serum antibody has also been detected using an IgM capture assay. In this assay, goat anti-human IgM is used to coat microtiter plates, and dilutions of the test serum are then applied. VLPs are added in the next step, and VLPs bound by virus-specific IgM are detected using hyperimmune anti-NV rabbit serum 240. An alternative method uses a virus-specific MAb for VLP detection 28. Antibody levels are four- to eightfold higher using the IgM capture assay compared to the assay in which IgM bound to VLPs is detected 240. In two different studies following experimental human infection, IgM capture assays detected IgM responses in 15 of 15 and 14 of 15 subjects, with infection documented by fourfold or greater IgG responses 28, 240.

Detection of infection caused by heterotypic HuCVs.

The serologic responses measured using VLP-based antibody detection EIAs have been characterized using sera collected during studies of experimental human infection and during evaluations of gastroenteritis outbreaks. Heterologous rNV IgG responses occur following experimental human infection with HV or SMA although they are present at a lower frequency and magnitude than is seen following infection with NV 240 or when rMX (SMA-like) VLPs are used in the assay 206. Heterologous rHV IgG responses also can be demonstrated following NV infection 41. The results are similar to those obtained using human reagents in blocking EIAs, although heterologous seroresponses as measured by the older and newer assays occurred in different subjects 177, 240. Heterologous seroresponses appear to be limited to subjects who also have an IgG seroresponse to homologous viral antigen and who are ill. Heterologous IgM and IgA responses occur infrequently 240.

Similar results have been obtained when these assays have been applied to sera collected during outbreak investigations 28, 105, 195, 206. IgG responses occur with a higher frequency and magnitude when the assay utilizes VLPs that are more closely related to the outbreak strain 105, 195. Noel et al. 195 found homologous IgG seroresponses to rNV VLPs when the infecting NLV was a genogroup I NLV with as much as 38.5% amino acid divergence from NV in the capsid region. In contrast, homologous seroresponses were seen for genogroup II NLVs only when the amino acid divergence from the test antigen was less than 6.5%. In general, the likelihood of detecting an IgG seroresponse for genogroup II NLVs was greatest when the test antigen was derived from a strain closely related to the infecting virus, less when the test antigen was derived from an unrelated genogroup II NLV, and least when the test antigen was rNV (genogroup I). Hale et al. 105 examined several outbreaks caused by genogroup II NLVs and found that rMX IgM responses occurred in 14 of 19 (74%) subjects with an IgG seroresponse. IgM responses occurred more frequently when the outbreak virus was MX-like (9 of 10) than when it was an unrelated genogroup II virus (4 of 9). Four of these subjects also had an rNV IgG seroresponse, but none of them had a rNV IgM seroresponse. Brinker et al. 28 obtained similar results applying the rNV and rMX IgM EIAs to genogroup I and genogroup II outbreaks. Twenty-four of 25 subjects infected with genogroup I viruses had rNV IgM responses, while only 3 of these subjects had rMX IgM responses; 28 of 47 subjects infected with genogroup II viruses had rMX IgM responses while none of them had rNV IgM responses. Taken together, these results indicate that IgM responses may be able to provide data on the genogroup of virus causing an infection.

The antibody detection EIAs have been used in seroprevalence surveys and in longitudinal studies of antibody acquisition 41, 54, 70, 82, 116, 118, 127, 163, 190, 193, 199, 204, 206, 207, 213, 227, 228, 236. These studies confirmed and extended the results obtained using human reagents showing that NLVs cause infection worldwide and seroprevalence increases with age. New findings include serologic evidence of NLV infection occurring in young children in developed countries that was not recognized in early studies 163 and of transplacental transfer of NLV-specific antibodies from mother to child 41, 118, 199, 206, 228. In addition, seroprevalence rates varied between regions within a country, between countries, and by the NLV VLP antigen used in the assay.

Nucleic Acid Detection

Nucleic acid detection assays are the third group of new assays that have been developed in the last decade since the cloning of the NV genome. Knowledge of the sequence of the NV genome led to the design of primers from the polymerase region that were able to amplify fragments of other NLVs and SLVs, and this led to sequencing of the complete genomes of many HuCVs. Although there have been a few reports of the use of hybridization assays, the primary nucleic acid detection assay that is used is RT-PCR. RT-PCR is currently being used worldwide because of the lack of a commercially available, broadly reactive EIA. Both nucleic acid detection diagnostic approaches will be discussed below.

Hybridization assays.

Only a few hybridization assays have been described for the detection of HuCVs. This is most likely due to the availability of the more sensitive RT-PCR assays at the time that cDNAs for HuCVs first became available. Jiang et al. 129 described a hybridization assay using 32P-labeled cDNAs covering the same region of the genome as was amplified in RT-PCR assays. Stool suspensions (10 to 50%) were extracted with trichlorotrifluoroethane, and the viral nucleic acids were partially purified from the aqueous phase by digestion with proteinase K, extractions in phenol-chloroform and chloroform, and precipitation in ethanol. The hybridization assay detected NV with a sensitivity similar to that of RIA, but detected 100-fold less viral RNA and detected virus in stool samples 27% less frequently than an RT-PCR assay applied to the same samples. Thus, the hybridization assay was unable to detect NV when low titers of virus were present in a stool sample 129.

A hybridization assay using a digoxigenin-labeled cDNA probe derived from the polymerase region of Sapporo virus has also been described 150. Viral nucleic acids were partially purified as described above, and approximately 105 viral particles could be detected per dot. This level of detection is lower than the 1 × 104 to 2 × 104 particles detected by RIA and EIAs specific for Sapporo virus. The interpretation of test results was also hampered by the colorimetric detection system. Some stool samples gave false-positive results due to the color of the stool or to nonspecific binding of the probe to substances in the stool. The problem of false-positive results was addressed by inclusion of digoxigenin-labeled vector (pBR322) DNA in the assay as a negative control. The signal intensities obtained with virus-specific and control probes were compared to reference dots containing 10-fold serial dilutions of Sapporo virus cDNA, and positive samples were those in which the reaction with the virus-specific probe was stronger than with the control probe.

The Sapporo virus-specific dot blot assay was used to evaluate 100 stool samples in which HuCVs were detected by electron microscopy. Eight of 10 samples that tested positive using the SLV/Sapporo/82 EIA were positive by the dot blot assay, and an additional 13 samples were EIA negative and dot blot hybridization positive. Seventy-seven samples were negative by both assays. The investigators speculated that the improved sensitivity of the dot blot hybridization assay compared to the EIA may have been due to the greater conservation of sequence among SLVs in the polymerase region (targeted in the dot blot assay) than in the capsid region (targeted in the EIA assay) or to the presence of substances in stool samples that had a greater inhibitory effect on EIA than on dot blot hybridization assays. A potential advantage of the dot blot hybridization assay over RT-PCR assays is the lower cost of the assay and decreased risk of cross-contamination. Nevertheless, RT-PCR assays have been the major nucleic acid detection assay used for the diagnosis of HuCV infections.

RT-PCR.

The first RT-PCR assays were described within 2 years of the initial report of the successful cloning of the NV genome 53, 129. Since then a number of different RT-PCR assay formats have been developed, and these assays have become one of the principal means for the diagnosis of HuCV infections. A number of factors can affect the sensitivity and specificity of RT-PCR assays, including the sample being assayed, the method used for purification of viral nucleic acids, the primers used in amplification, and the method used for interpretation of test results. Approaches to addressing each of these factors are discussed below.

(i) Extraction methods.

Clinical samples frequently contain substances that can inhibit the enzymatic activity of the reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase enzymes used in RT-PCR assays. Thus, it is usually necessary to partially purify viral nucleic acids or otherwise prepare the sample prior to the performance of the RT-PCR assay. Two major considerations in selecting an extraction method are its efficiency of viral nucleic acid recovery and its ability to remove or inactivate RT-PCR inhibitors. Secondary considerations include the ease of performance of the method and the number of samples that can be processed at one time. A number of different approaches for viral nucleic acid purification from stool samples have been reported. Those that have been used for the detection of HuCVs are shown in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Extraction methods used to prepare a clinical sample for RT-PCR

| Method | References |

|---|---|

| Antibody capture | 74, 219 |

| Chelation of multivalent cation impurities | 103, 119 |

| Exclusion chromatography | 53, 103 |

| Guanidinium-phenol-chloroform + alcohol precipitation | 63, 232 |

| GTC-silica | 3, 101 |

| Heat release | 32, 221 |

| PEG-CTAB | 103, 129 |

Jiang et al. 129 evaluated a number of different methods for the removal of inhibitors. Suspensions of stool samples (10 to 50%) were made, and the suspension was extracted with trichlorotrifluoroethane prior to further processing. Phenol-chloroform extraction, heating, and dialysis were all ineffective at removing the inhibitory substances present in stool samples, and oligo(dT)-cellulose chromatography of the sample was described as inefficient. The addition of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) after concentration by precipitation with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and proteinase digestion significantly improved the signal obtained following RT-PCR, and this method has been used in a number of subsequent RT-PCR studies of HuCVs 43, 127, 146, 159, 161, 188, 248, 255. Inhibitors can persist in some samples extracted with the PEG-CTAB method. Schwab et al. 221 and Hale et al. 103 found that approximately 13% (6 of 45) and 19% (7 of 36), respectively, of extracted samples still contained inhibitors that could prevent the detection of viral nucleic acids.

Modifications of the RNA extraction method of Chomczynski and Sacchi 39 have been used successfully to extract viral RNA from stool samples 63, 232. The method utilizes a mixture of guanidinium thiocyanate (GTC), phenol, and chloroform to extract the sample, followed by chloroform extraction and precipitation of nucleic acids in alcohol. The principal reagent is commercially available from a number of vendors (RNAzol, Ultraspec, and TRIzol). A variation on the GTC-based extraction procedure was described by Boom et al. 26, in which a GTC-containing buffer is used to release viral RNA from the viral capsid. The viral RNA is adsorbed onto size-fractionated silica particles and washed in successive steps with a second GTC-containing buffer, 70% ethanol, and acetone. The viral RNA is then eluted from the silica particles with water. Other variations have also been used successfully 3, 101. The GTC-silica method has been reported to be quite successful in removing inhibitors of PCR in two comparative studies, performing better than the PEG-CTAB method in the detection of NLVs 103 and being approximately equivalent to PEG-CTAB for the detection of hepatitis A virus in stool samples 8.

Exclusion chromatography using spin columns containing Sephadex G200 was one of the original methods used to extract virus from stool samples 53. Although the method is sensitive, it is inconsistent at removing inhibitors from clinical samples 103. Similarly, a method based on the chelation of multivalent cation impurities has been used successfully for detection of NLVs but is unreliable at removing inhibitors of RT-PCR 8, 103. Unexpectedly, NLVs can be detected by RT-PCR in stool samples after simple heating of the sample to 95 to 99°C for 5 min 32, 221. The heat may inactivate some inhibitors and is thought to denature the viral capsid, allowing the release of viral RNA. Prior to the heat release procedure, 10 to 20% suspensions of the fecal samples are clarified and extracted with trichlorotrifluoroethane or pelleted through a 45% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion. The trichlorotrifluoroethane-treated samples must be diluted 100-fold, as amplification is inhibited in the majority of specimens at a lower dilution 221.

Antibody capture has been used for virus purification prior to amplification 74, 219. Virus-specific antibodies are bound in a 96-well plate or to paramagnetic beads before exposure to a virus-containing sample. After an incubation period to allow antigen capture, the wells or beads are washed repeatedly to remove inhibitors and other substances. Viral genomic RNA is then released from its capsid by heating. This method has worked well for hepatitis A virus, but its use in the detection of HuCVs has been limited. The principal reason this method has not been explored further is the lack of high-titered antisera that react with a broad range of NLVs. Nevertheless, Schwab et al. 219 were able to use human immunoglobulin preparations as a source of antibody to detect NLVs from water samples in which viruses had been concentrated by filtration and PEG precipitation. Polyclonal hyperimmune animal sera have also been coupled to paramagnetic beads and used to purify NV from fecal specimens prior to RT-PCR amplification 74. This strategy was found to yield a greater number of positive RT-PCR results from stools collected during experimental human infection studies than other processing protocols. As broadly reactive antisera become available, further studies of this extraction method are likely to be performed.

(ii) Primer selection.

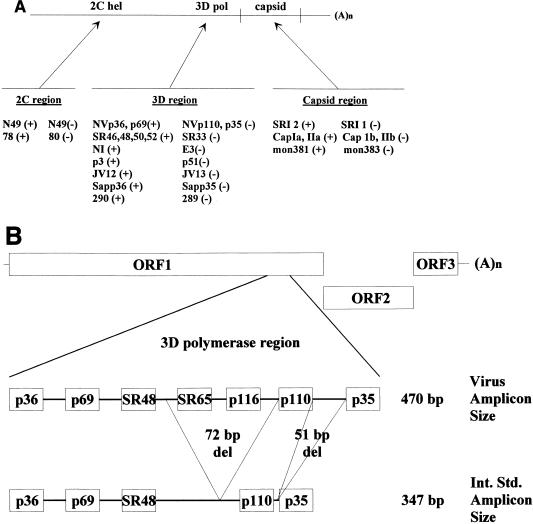

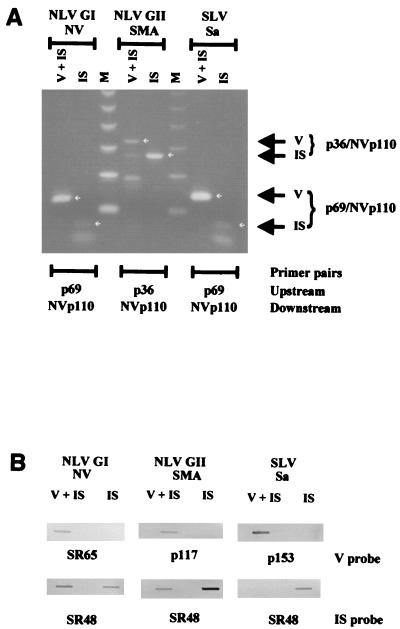

The sensitivity and specificity of RT-PCR assays depend in large part on primer selection. Several factors affect the ability of a primer pair to detect a given NLV or SLV strain, including primer sequence, the amount of virus present in the sample to be assayed, and the temperature used for primer annealing during the PCR amplification process. The genetic diversity of NLVs and SLVs has made it difficult to select a single primer set with adequate sensitivity and specificity to detect all NLVs. In general, regions of the genome with the greatest degree of conservation between strains within the genera and within genogroups have been targeted for amplification and primer design (Fig. 4A). But even within these regions, the nucleotide identity can be as little as 36% (2C helicase region) to 53% (3D polymerase region) between strains of different genogroups 5, 43, 182, 197, 245, 248, 255, 256. Within a genogroup of NLVs, greater conservation is seen, but the nucleotide identity between strains can still be as little as 60 to 64% 245. These observations have led to the design and use of primer sets targeting multiple areas of the viral genome (Fig. 4A, Table 6).

FIG. 4.

(A) Schematic representation of the calicivirus genome and the regions amplified by common primer pairs. Modified from reference 220 with permission from Technomic Publishing Co, Inc., copyright 2000. See Table 6 for further details about primer sequences. hel, helicase; pol, polymerase. (B) Schematic representation of the NLV genome from which an internal standard control for genogroup I NLVs was made. The relative locations of selected primers and probes are noted for virus and internal standard (Int. Std.) RNA. The internal standard control RNA yields amplicons that are 123 bp shorter (347 bp) than those from NV genomic RNA (470 bp). A portion of the genomic sequence targeted by virus-specific probes (e.g., SR65 and p116) is not present in the internal standard control, allowing differentiation of virus-specific and internal standard amplicons by nucleic acid hybridization 221.

TABLE 6.

Common HuCV-specific primers used in RT-PCR assays

| Primer | DNA sequence (5′ to 3′) | Genomic locationa | Sense | Viruses amplifiedb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p78 | GGGCCCCCTGGTATAGGTAA | 1682–1701 (2C helicase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 248 |

| p80 | TGGTGATGACTATAGCATCAGACACAAA | 1943–1970 (2C helicase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII) | 248 |

| N49(+) | CACCACCATAAACAGGCTG | 2215–2233 (2C helicase) | + | NLVs (GI) | 181 |

| N49(−) | AGCCTGATAGAGCATTCTTT | 2419–2438 (2C helicase) | − | NLVs (GI) | 181 |

| p36 | ATAAAAGTTGGCATGAACA | 4487–4505 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII), SLVs | 248 |

| Sapp36 | GTTGCTGTTGGCATTAACA | 4487–4505 (3D polymerase) | + | SLVs | 180 |

| JV12 | ATACCACTATGATGCAGATTA | 4552–4572 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 246 |

| P290 | GATTACTCCAAGTGGGACTCCAC | 4568–4590 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII), SLVs | 125 |

| p3 | GCACCATCTGAGATGGATGT | 4685–4704 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 188 |

| p69 | GGCCTGCCATCTGGATTGCC | 4733–4752 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII), SLVs | 248 |

| SR46 | TGGAATTCCATCGCCCACTGG | 4766–4786 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 3 |

| SR48 | GTGAACAGCATAAATCACTGG | 4766–4786 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 3 |

| SR50 | GTGAACAGTATAAACCACTGG | 4766–4786 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 3 |

| SR52 | GTGAACAGTATAAACCATTGG | 4766–4786 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GI & GII) | 3 |

| NI | GAATTCCATCGCCCACTGGCT | 4768–4788 (3D polymerase) | + | NLVs (GII) | 83 |

| JV13 | TCATCATCACCATAGAAAGAG | 4858–4878 (3D polymerase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII) | 246 |

| E3 | ATCTCATCATCACCATA | 4865–4881 (3D polymerase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII) | 83 |

| NVp110 | AC(A/T/G)AT(C/T)TCATCATCACCATA | 4865–4884 (3D polymerase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII), SLVs | 159 |

| P289 | TGACAATGTAATCATCACCATA | 4865–4886 (3D polymerase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII), SLVs | 125 |

| SR33 | TGTCACGATCTCATCATCACC | 4868–4888 (3D polymerase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII) | 3 |

| p51 | GTTGACACAATCTCATCATC | 4871–4890 (3D polymerase) | NLVs (GI & GII) | 188 | |

| p35 | CTTGTTGGTTTGAGGCCATAT | 4936–4956 (3D polymerase) | − | NLVs (GI & GII), SLVs | 248 |

| Sapp35 | GCAGTGGGTTTGAGACCAAAG | 4936–4956 (3D polymerase) | − | SLVs | 20 |

| SRI-2 | AAATGATGATGGCGTCTA | 5356–5373 (capsid) | + | NLVs (GI) | 101 |

| mon381 | CCAGAATGTACAATGGTTATGC | 5362–5383* (capsid) | + | NLVs (GII) | 195 |

| CapIIa | CIAGAATGTAIAA(C/T)GG(G/T)TATGC | 5362–5383* (capsid) | + | NLVs (GII) | 89 |

| CapIIb | TGIIAGAAAIT(A/G)TTICI(A/G)ACATC(A/T)GG | 5559–5584* (capsid) | − | NLVs (GII) | 89 |

| CapIa | CICAAATGTAIAATGG(C/T)TGGGT | 5647–5668 (capsid) | + | NLVs (GI) | 89 |

| SRI-1 | CCAACCCA(A/G)CCATT(A/G)TACAT | 5652–5671 (capsid) | − | NLVs (GI) | 101 |

| mon383 | CAAGAGACTGTGAAGACATCATC | 5661–5683* (capsid) | − | NLVs (GII) | 195 |

| CapIb | TGIIA(A/G)AGIACATTICI(A/T)ACATC(C/T)TC | 5844–5869 (capsid) | − | NLVs (GI) | 89 |

The majority of primers have been designed to amplify the most conserved region of the genome, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase region 3, 20, 83, 125, 159, 180, 188, 220, 248. Although a number of primer pairs have been described, those described by Ando et al. 3, Green et al. 83, and Le Guyader et al. 159 have been the most frequently used (Fig. 4A, Table 6). Ando et al. 3 described a multiplex approach in which cDNA is made using a single primer (SR33) to initiate reverse transcription and four additional primers are used during the amplification process, three (SR48, SR50, and SR52) to amplify genogroup I NLVs and one (SR46) to amplify genogroup II viruses. Green et al. 83 described a different primer pair (E3 and NI) to amplify group II NLVs, and Le Guyader et al. 159 described a degenerate primer (NVp110) that can prime cDNA synthesis of group I and II NLVs and some SLVs. One of the problems associated with the genogroup II primer pairs (NVp110/NI and SR33/SR47) that amplify the polymerase region is that only 76 to 81 unique bases of sequence data can be obtained from the amplified products. Jiang et al. 125 recently described a primer pair, P289 and P290, that will amplify genogroup I and II NLVs and SLVs, yielding RT-PCR products from which almost 300 unique bases of sequence data can be derived. The P289 primer sequence is identical to the NVp110 and E3 primers in the 12 nucleotides at the 3′ end of the primer; the 5′ end has three nucleotide differences and is two bases longer than NVp110 and five bases longer than E3. These data suggest that NVp110, E3, and P289, whose 3′ ends are the reverse complement of the viral genome at the YGDD motif site of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, can successfully prime cDNA synthesis for a large number of NLVs and SLVs. Occasionally, primers designed based on the sequence of a locally circulating strain have performed better than other primer pairs 217. Other primers have also been described for the specific amplification of SLVs 20, 180, 244, 256.

Other regions of the viral genome have been targets of amplification (Table 6, Fig. 4A), including the 2C helicase, the capsid region, and ORF3 53, 89, 101, 181, 188, 195, 248. The most common reason to target another area of the genome is to generate additional sequence data that might be useful in distinguishing or identifying unique viral strains. Toward this end, a RT-PCR assay that amplifies the 3′ end of the viral genome has been described 4. In general, assays using primers to amplify nonpolymerase regions of the viral genome are less broadly reactive (amplify a smaller number of virus strains due to the greater genetic diversity in these regions) or require a greater amount of virus to be present in the sample (e.g., to amplify ∼3 kb of virus genome).

Very few studies have been reported that describe the quantity of virus genome that must be present in order for a primer pair to detect the virus 159. Instead, most studies only report whether a primer pair can detect a virus strain without regard to the amount of virus present in the sample. However, successful detection of virus may be enhanced when larger quantities of virus are present. For example, Le Guyader et al. 159 noted 10- to 1,000-fold differences in the quantities of several NLV strains that could be detected by two primer pairs, NVp110/p36 and NVp110/p69. In other words, when a large quantity of a virus strain is present, both primer pairs can successfully detect it, but when small quantities of the strain are present, only one primer pair allows successful virus detection. The reason for the differences in virus detection is primer homology, with primers having lower homology requiring the presence of larger quantities of virus for successful amplification to occur. Another approach used to improve the chances of successful amplification has been to lower the primer annealing temperature to as low as 37°C 248. This strategy has the disadvantage of increasing the likelihood that nonspecific amplicons will be generated and may increase the amount of virus that must be present in the sample for successful virus detection.

The use of nested or seminested PCR is another method that has been used to increase the likelihood of detecting NLVs 84, 200, 234. This approach utilizes two rounds of PCR amplification, with one (seminested) or both (nested) primers used in the second round of amplification targeting a region of the genome inside that targeted by the primers used in the initial amplification. This strategy has been reported to be 10 to 1,000 times more sensitive than single-round RT-PCR 84 and has also been used to detect the presence of multiple viral strains within a single sample 200, 234. However, a major disadvantage of this approach is the increased and very real possibility that carryover contamination may occur between samples.

(iii) Other PCR conditions.

The conditions (e.g., magnesium concentration and primer annealing temperature) of the RT-PCR assay are dictated, in part, by the primers used. The use of different DNA polymerases during the PCR amplification process has also been reported. Ando et al. 4 used a combination of Taq DNA polymerase and Pwo DNA polymerase for the amplification of a large (3 kb) fragment of the viral genome. Schwab et al. 222 utilized Tth polymerase in place of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase and Taq polymerase and found that detection of NV in the Tth polymerase-based assay was comparable to that in the two-enzyme system. The use of a single enzyme for reverse transcription and DNA amplification also allowed the use of thermolabile uracil-N-glycolase (UNG) for the prevention of carryover contamination 222. dUTP is used in place of dTTP in the RT-PCRs, and the UNG degraded deoxyuracil-containing amplicons added (or carried over) to the reaction tube. The UNG is then inactivated by heating, and the viral RNA is amplified.

(iv) Confirmation of PCR products.

A number of methods can be used to interpret the results of a PCR method. One of the simplest is gel electrophoresis. If a band of the size predicted from primer selection is seen following electrophoresis, the PCR is considered positive. This method has been used for NLV RT-PCR assays 10, 84, but it can yield false-positive results 11, 12. Nonspecific amplification of DNA occurs, particularly when more than 30 cycles of amplification are used, and the nonspecifically amplified DNA will occasionally migrate in a fashion similar to that expected for virus-specific amplicons. If this happens, the nonspecific amplification products may be misinterpreted as being virus-specific amplicons. Such nonspecific bands are frequently seen following the assay for NLVs in stool and shellfish samples 12. Because of the potential false-positive results in the visual interpretation of gels, it is essential to confirm the specificity of the amplicons by a second method.

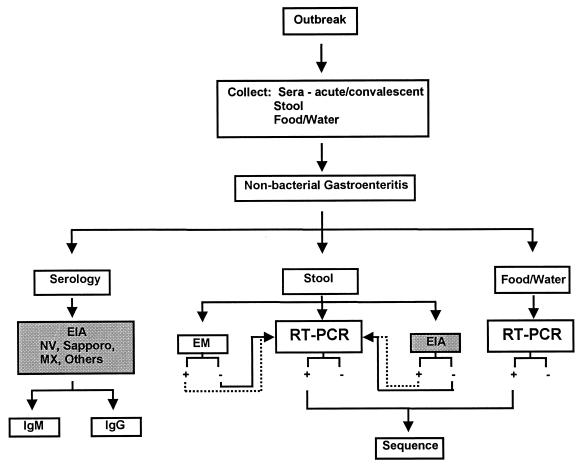

The use of a hybridization assay is probably the simplest approach to interpret and confirm PCR assays. Hybridization assays can be set up in a number of different ways. The most common include dot or slot blot hybridization, liquid hybridization, and Southern blot hybridization. In these assays, a virus-specific probe is labeled and hybridized with the PCR products, and the presence or absence of the label is detected. Some of the more common labels include 32P, digoxigenin, and biotin. One of the limitations of hybridization assays when applied to NLV RT-PCR assays is that the variability of the genomic sequence in the NLVs makes it difficult to select a single or even a small number of probes that can detect all possible NLV sequences 159. Nevertheless, a small number of probes have been effective for the detection of the majority of circulating NLVs when the DNA being amplified was homologous to the polymerase region of the NLV genome 3, 83, 159. The time required to perform the hybridization assay can be shortened without loss of sensitivity by using a direct EIA format. Virus-specific amplicons are captured with a biotinylated probe anchored to a streptavidin-coated, 96-well plate, and the probe-amplicon hybrid is detected using an anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibody conjugate (R. L. Atmar and K. J. Schwab, unpublished data). A reverse-line blotting strategy is another approach that has simplified the use of multiple probes at one time and yielded both specificity data and data on the genetic relatedness (genotype) of the HuCV detected to reference strains 247. HuCVs are amplified using biotinylated primers, and virus-specific amplicons are captured during hybridization by one of the multiple probes that are linked to the membrane in individual dots on a blot. Biotinylated products are detected by streptavidin-enzyme conjugates.