Abstract

Göran Tomson and colleagues argue that our ability to control pandemics requires global action to counter inequalities from demographic, environmental, technological, and other megatrends

Humankind has set a historical precedent in the past century with enormous social and economic transformations, advancement, and prosperity in many parts of the world. These have been supported by technological innovations, increased life expectancy, and changing governance from autocratic to democratic in many countries. However, socioeconomic disparities remain worldwide, limiting the achievement of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.1

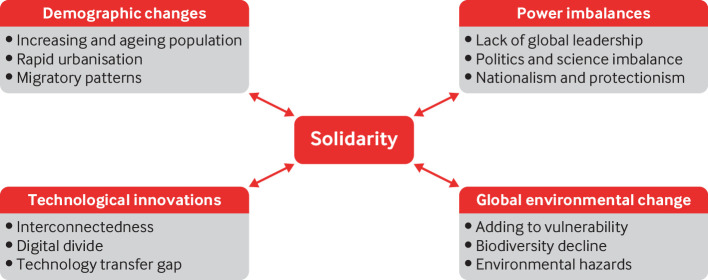

An important reason for these disparities is that megatrends—activities, movements, or patterns that fundamentally alter individual, social, and technological behavioural structures—have never been so pervasive, explosive, or accelerated.2 Megatrends such as demographic changes, global environmental change, power imbalances, and technological innovations are having long lasting effects.3 Adding to these, gender inequality has failed to recognise and reward women’s potential.4 The scarcity of natural resources and increased consumption have reinforced the competition for global resources, further intensifying distribution inequities. Because of these inequities, the covid-19 pandemic has hit unevenly.

Automation after the industrial revolution transformed the labour market, population growth caused increased urbanisation, while fossil fuels carbon emissions, urbanisation, and environmental pollution have accelerated the global threat of climate change and are still spiralling out of control. Demographic changes have led us to encroach on habitats of species that are hosts to viruses with pandemic potential and increased their opportunities to jump from one species to another.5 Once new viruses have entered a human host, our interconnectedness resulting from urbanisation and mobility allow them to spread quickly and effectively. We witnessed this scenario in the initial phase of the covid-19 pandemic when the virus got a foothold on all continents within weeks of its first known occurrence in Wuhan, China.6

Megatrends enabled covid-19 to hit unevenly

Covid-19 has had uneven global effect because of existing inequity. Figure 1 shows four megatrends that have created the vulnerabilities exacerbated by covid-19.

Fig 1.

Four megatrends creating vulnerability and the need for solidarity during covid-19

Demography and context

The trajectory of the pandemic in different communities has been influenced by population characteristics. Virus transmission accelerated in households with cramped living conditions and those without basic sanitary infrastructure. Urbanisation has constrained prevention and mitigation efforts and increased vulnerability.7 Ageing populations with a high prevalence of underlying conditions faced a high death toll, while younger populations in low and middle income countries were disproportionally affected by the socioeconomic consequences of lockdown and other public health measures.

Covid-19 has unveiled existing inequities to the extent that they can no longer be ignored. National strategies to combat the pandemic, such as lockdowns and sweeping restrictions on movement, have undermined global economic security, increased inequalities in access to resources, diminished the enjoyment of rights to healthcare, education, and social protection, and exacerbated discrimination, gender inequality, xenophobia, and domestic violence.8 The effects were mostly felt by populations often already excluded from healthcare and job opportunities, such as minority groups, indigenous populations, migrants, and informal economy workers, leading to their further isolation and unemployment.9 10

Environmental change

Global environmental change takes a hefty toll on populations in low and middle income communities, such as droughts leading to diminished harvests and poor diets, heatwaves, lack of green spaces, high air pollution, and soil erosion. These changes further reinforced socioeconomic vulnerabilities at both local and global levels.11 They have exacerbated morbidity and mortality and added burden to the overwhelmed health system dealing with covid-19.12 Habitat destruction has also increased the spread of SAR-CoV-2.13

Technological innovation

The covid-19 pandemic has highlighted differences in access to technological innovations. For example, research shows that half of the world’s population, including 360 million young people, does not have access to the internet.14 15 The “digital divide” reinforces socioeconomic vulnerabilities and adversely affects those with the least digital skills, such as elderly people.16 17 School closures because of covid-19 have affected the learning of children without access to digital technology and online learning methods, affecting their health and wellbeing now and in the future.18 When children are unable to access a safe school environment, school dropout rates often increase, children and adolescents experience higher levels of exploitation and violence, and their future employment opportunities are harmed.10

Although the burgeoning use of social media worldwide has provided opportunities to share validated information during the covid-19 pandemic,19 it has also been a driver of false information, fuelling conspiracies and supporting detrimental social behaviours. However, social media use has also been important for increasing a sense of community and connection during lockdowns and movement restrictions put in place to slow covid-19 transmission.

Power imbalances

Over the past few decades, power imbalances have contributed significantly to inequities in health. Notably, many countries have effectively ceded power to international financial institutions and multinational corporations.20 This reduced their capacity to meet population health needs, while private concentration of wealth and power grew considerably.20 21 At the same time, the UN system has weakened—for example, the World Health Organization has seen its authority eroded, with a gradual reduction of financial support from all member states and threatened withdrawal by the US.22 This has hampered international coordination and information exchange during the pandemic.

The trend towards increased nationalism and protectionism has amplified these effects.23 We have seen politics often take precedence over science. Covid-19 has highlighted the conflict between medical and public health experts on the one hand and political decision makers on the other when expert advice is not aligned with political goals.24

The pandemic has exposed fissures and flaws in our societies that need to be amended so that the communities can build societal resilience before the next pandemic hits.25 It has also laid bare the growing crisis in global governance for health to tackle these challenges to humanity. While there are mechanisms for supranational governance, arguably no single or combined supranational governance mechanism effectively addresses the major determinants of health and the issues arising between science and politics.20

Need for solidarity and universal preparedness

The interplay between megatrends and covid-19 shows the need for structural responses to the systemic drivers of health and social inequities within and across countries. The pandemic should unite the entire global community to build societal resilience to cope with the next crisis.25 It is a stark illustration of why solidarity and unity of action is required to mitigate or reverse the megatrends that have left the world vulnerable to the spread of disease. We believe solidarity is the key response strategy.

Solidarity is building on elements of “relationships among individuals, peoples, and states.”26 It underpins global partnerships and is an essential component of efforts to realise all human rights, including internationally agreed development goals. Justice is a vital component of solidarity and requires governments to respect, protect, and fulfil the rights of citizens while contextualising their response to citizens’ different needs.26

Solidarity can also help control pandemics. With increasing population density, biodiversity loss, lack of sustainable agriculture practices, the digital divide, and global interconnectedness, we need to start being responsible to one another and the generations to come. Solidarity asks for respect and implementation of treaties that secure human rights, right to development, political rights, economic rights, accountability, and participatory action. We know that nobody is safe until everybody is safe.

Solidarity can be enacted through universal preparedness for health across geographical and generational borders and socioeconomic groups. Universal preparedness for health is a cross-sectoral challenge that extends far beyond the healthcare sector. It goes beyond universal health coverage, which includes financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable medicines and vaccines.1 Universal preparedness for health adds the “time” dimension, as being prepared is a global responsibility to avoid the next global emergency. 27 A starting point would be to revisit and strengthen the International Health Regulations sidelined in the covid-19 pandemic, but this is not enough to reduce the vulnerability created by megatrends that cut across sectors such as health, education, social protection, climate, and urban development.

Universal preparedness requires a trans-sectoral approach to mitigate the structural drivers of health and social inequities, including multidimensional poverty and discrimination. It requires tackling the increasingly important political determinants of health, such as the growth and influence of transnational corporations that dwarf the economic capacity of countries and international organisations.20 Such an approach is not emphasised enough in current global health efforts.

Universal preparedness will therefore require a proactive use of resources to build societal resilience and reduce the structural inequalities that hinder development and perpetuate poverty. For example, social protection measures will be needed for those who are most vulnerable, such as those who are self-employed or in insecure work. More targeted support for people who have fallen behind and more equitable distribution of resources to meet people’s needs are essential. Universal preparedness for health requires changes to the global financing architecture to secure sustainable funding, including domestic and international financing, which are key to safeguarding health and development outcomes.28

Stronger international and national collaboration through data sharing and research is critical for understanding and reducing structural vulnerabilities that have contributed to some groups being hit harder by covid-19. We must be better prepared with more evidence to inform how policies could adversely affect the most vulnerable society in terms of economic and social costs.

Being prepared also means investing in people. In addition to promoting population health through structural measures for social equality, universal preparedness requires stronger and more accountable people-centred health systems.29 30 Fair and effective governance at both national and global levels, which engages multiple stakeholders, including citizens, in decision making is fundamental to modern democracies and to building solidarity.31

Global governance to support solidarity

Megatrends and their interplay with covid-19 present major challenges to the global community and require a multisectoral and internationally collaborative response. To support solidarity and universal preparedness in a post-covid world we must unite around a global, multisectoral governance mechanism that tackles the determinants of health at global, national, and local levels.31 32 As the Lancet Covid-19 Commission suggests, global cooperation, social justice, sustainable development, and good governance are needed to rebuild with resilient health systems and global institutions and to transform economies based on sustainable and inclusive development. Global governance mechanisms would also overcome the profound challenges faced by multilateral institutions caught in the middle of big power politics during covid-19.33

The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPR) has an opportunity to go beyond reviewing how countries and WHO responded to covid-19 to propose such a global governance mechanism.32 The Lancet Covid-19 Commission should do the same.33 We need to be guided by the principles of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to mitigate the effect of megatrends that enabled covid-19 to exacerbate existing inequalities within and across countries.1 Global collective action in support of solidarity and universal health preparedness is critical for a more resilient and inclusive post-covid world.

Key messages.

The covid-19 pandemic has unveiled inequities and laid bare the growing crisis in global governance for health

Global demographic and environmental trends have long-lasting effects on global health and created the vulnerabilities exacerbated by covid-19

This interplay shows the need for solidarity within the global community to build resilient systems before the next pandemic

A global, multisectoral governance mechanism is needed to create the conditions to support solidarity and universal preparedness for health

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Hamilton for her valuable input, including technical help with the figure, and the two reviewers.

Contributors and sources: GT, SC, OPO, SSP, SR, RKW, and AEY conceived the article. GT and SC wrote the first draft and successive versions of the manuscript and coordinated inputs from all co-authors. GT, SC, OPO, SSP, SR, RKW, and AEY all contributed to the final version’s writing, approved by all co-authors. GT attests that all authors meet the authorship criteria.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a collection launched at the Prince Mahidol Awards Conference (PMAC) in January 2021. Funding for the articles, including open access fees, was provided by PMAC. The BMJ commissioned, peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish these articles. David Harper and an expert panel that included PMAC advised on commissioning for the collection. Rachael Hinton and Kamran Abbasi were the lead editors for The BMJ.

References

- 1.United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015 https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf.

- 2.OECD. Megatrends affecting science, technology and innovation. OECD Science, Technology, and Innovation Outlook 2016. https://www.oecd.org/sti/Megatrends%20affecting%20science,%20technology%20and%20innovation.pdf.

- 3. Haq L. Megatrends: Part 1 of 3. Globalisation to herald long-term power shift. Health Serv J 2012;122:28-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. George AS, Amin A, De Abreu Lopes CM, Ravindran TKS. Structural determinants of gender inequality: why they matter for adolescent girls’ sexual and reproductive health. BMJ 2020;368:l6985. 10.1136/bmj.l6985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khetan AK. Covid-19: why declining biodiversity puts us at greater risk for emerging infectious diseases, and what we can do. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:2746-7. 10.1007/s11606-020-05977-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee A. Wuhan novel coronavirus (COVID-19): why global control is challenging? Public Health 2020;179:A1-2. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Orcutt M, Patel P, Burns R, et al. Global call to action for inclusion of migrants and refugees in the COVID-19 response. Lancet 2020;395:1482-3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30971-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations. Human Rights: we are all in this together. 2020. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief_on_human_rights_and_covid_23_april_2020.pdf.

- 9. Kluge HHP, Jakab Z, Bartovic J, D’Anna V, Severoni S. Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. Lancet 2020;395:1237-9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30791-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lambert H, Gupte J, Fletcher H, et al. COVID-19 as a global challenge: towards an inclusive and sustainable future. Lancet Planet Health 2020;4:e312-4. 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Wit W, Freschi A, Trench E. Covid 19 : urgent call to protect the nature. 2020 https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/covid19-urgent-call-to-protect-people-and-nature.

- 12. The Lancet . Climate and COVID-19: converging crises. Lancet 2021;397:71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations. Report of the UN Economist Network for the UN 75th anniversary. Shaping the trends of our time. 2020 https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2020/09/20-124-UNEN-75Report-2-1.pdf.

- 14. Online learning cannot just be for those who can afford its technology. Nature 2020;585:482. 10.1038/d41586-020-02709-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makri A. Bridging the digital divide in health care. Lancet Digit Health 2019;1:e204-5 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30111-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e243-4. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watts G. COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e395-6. 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clark H, Coll-Seck AM, Banerjee A, et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO-UNICEF-Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020;395:605-58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cinelli M, Quattrociocchi W, Galeazzi A, et al. The covid-19 social media infodemic. Sci Rep 2020;10:16598. 10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ottersen OP, Dasgupta J, Blouin C, et al. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet 2014;383:630-67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62407-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spash CL. ‘The economy’ as if people mattered: revisiting critiques of economic growth in a time of crisis. Globalizations 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1080/14747731.2020.1761612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gostin LO, Moon S, Meier BM. Reimagining global health governance in the age of covid-19. Am J Public Health 2020;110:1615-9. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Barneveld K, Quinlan M, Kriesler P, et al. The covid-19 pandemic: lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ Labour Relat Rev 2020;31:133-57. 10.1177/1035304620927107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gonsalves G, Yamey G. Political interference in public health science during covid-19. BMJ 2020;371:m3878. 10.1136/bmj.m3878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kickbusch I, Leung GM, Bhutta ZA, Matsoso MP, Ihekweazu C, Abbasi K. Covid-19: how a virus is turning the world upside down. BMJ 2020;369:m1336. 10.1136/bmj.m1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OHCHR. Draft declaration on the right to international solidarity. 2020 https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Solidarity/DraftDeclarationRightInternationalSolidarity.pdf.

- 27. Ottersen OP, Engebretsen E. COVID-19 puts the sustainable development goals center stage. Nat Med 2020;26:1672-3. 10.1038/s41591-020-1094-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Strengthening preparedness for health emergencies; implementation of international health regulations (IHR, 2005). 2020 https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB146/B146_R10-en.pdf.

- 29. Bigdeli M, Rouffy B, Lane BD, Schmets G, Soucat A, Bellagio Group . Health systems governance: the missing links. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002533. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abimbola S, Negin J, Jan S, Martiniuk A. Towards people-centred health systems: a multi-level framework for analysing primary health care governance in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan 2014;29(Suppl 2):ii29-39. 10.1093/heapol/czu069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamin AE. When misfortune becomes injustice: evolving human rights struggles for health and social equality. Stanford University Press, 2020. 10.1515/9781503611313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO director-general opening remarks at the member state briefing on the covid-19 pandemic evaluation, 9 Jul 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-opening-remarks-at-the-member-state-briefing-on-the-covid-19-pandemic-evaluation-9-july-2020 .

- 33. Sachs JD, Horton R, Bagenal J, Ben Amor Y, Karadag Caman O, Lafortune G. The Lancet COVID-19 Commission. Lancet 2020;396:454-5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31494-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]