Abstract

Background:

Short-term complications after root canal therapy (RCT) include mild pain or flare-up. Patients regard these complications as a benchmark for the assessment of clinician's abilities. In this context, the evidence for recommending either one- or two-visit RCT is not consistent.

Aims:

This study aims to compare the prevalence of postoperative pain and tenderness to percussion after single-visit (SV) versus two-visit RCT on the mandibular first molar.

Materials and Methods:

The study was registered with www.ctri.nic.in (CTRI/2019/05/019067). Seventy individuals requiring RCT on a mandibular first molar were selected and randomly ascribed to either single- (Group 1, n = 35) or two-visit RCT (Group 2, n = 35). Postoperative pain levels were assessed using heft parker visual analog scale. The treated teeth were appraised for tenderness to percussion after 1 week of obturation.

Statistical Analysis:

Thirty-four patients were evaluated in each group: One patient, each, dropped out from both the groups. The data analysis was done using Student's t-test and Chi-square test.

Results and Conclusion:

Pain score in multiple-visit (MV) was significantly higher than SV after 12- (P = 0.039) and 48 h (P = 0.043). Short-term postoperative pain was higher in MV than SV RCT of mandibular first molar teeth.

Keywords: Calcium hydroxide, percussion, postoperative pain, root canal therapy, tenderness, visual analog scale

INTRODUCTION

Root canal therapy (RCT) requires removing organic tissue, debris, and pathogenic microbes from the root canal system utilizing mechanical instrumentation associated with copious irrigation with disinfectant agents. Two approaches are advocated to unravel this problem. In the first approach, remaining bacteria are eradicated or prohibited from repopulating the root canal system by giving an inter-appointment dressing into the root canal. However, even a negative culture prior to obturation does not guarantee healing in all situations.[1]

Another approach aims to eliminate residual microbes or render them unhazardous by entombing. Complete and three-dimensional obturation deprives the microbes of nourishment and the space required to thrive and reproduce. The treatment is completed in one visit. The sealer's antimicrobial activity or the zinc ions of gutta-percha can destroy the remaining bacteria.[1]

Short-term complications after root canal treatment include postoperative inflammation of periapical tissues leading to mild pain or flare-up. Patients might regard postoperative pain and flare-up as a yardstick by which the operator's abilities are assessed. The pain perception depends on the tissue damage severity, and the persistence of the injury source determines the outcome of RCT.[2]

The evidence for recommending either one or multiple visits (MV) to RCT is not consistent. Moayad Ahmed Alomaym et al.[3] assessed the incidence and severity of postobturation pain and deduced that there was a statistically significant less incidence of pain in MV groups than single–visit (SV) one. Singh et al.[4] inferred that the mean pain score in the SV was lower than that of the MV group. However, the difference was statistically insignificant. Other studies[5,6] concluded that there was no significant difference in postoperative pain between SV and MV treatment.

As the usage of newer rotary nickel–titanium instruments increases, a randomized clinical trial comparing SV and MV RCT, both done using such instruments, is desirable. Hence, this study primarily aims to compare postobturation pain prevalence at 6-, 12-h, 1-, and 2-day after SV versus two-visit RCT on the mandibular first molar. The secondary aim is to compare tenderness on percussion after 1 week of treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional Ethics Committee clearance was acquired, and the study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry - India (CTRI/2019/05/019067).

Selection of subjects

Ninety patients seeking RCT of mandibular first molars were screened. Fifteen individuals did not meet the criteria for inclusion, and five patients did not consent to participate. Seventy patients were recruited, and their informed consent was obtained.

Inclusion criteria

The patient should consent to the planned SV or two visit treatment

Moderately curved root canals.

Exclusion criteria

Patients having any systemic disease

Pregnant patients

Teeth with calcified canals, unusual canal morphology, teeth with extra root or procedural error during treatment

Teeth with periapical radiolucency of size >0.5 cm

A patient who took antibiotics and/or analgesics right after the first appointment of the therapy.

Sample size

The sample size was estimated using the formula: n = taking the significance level at 5% and the test's power at 80%. The sample size estimated was 30 patients per group and was appraised as 35 patients per group to compensate for dropouts during follow-up.

taking the significance level at 5% and the test's power at 80%. The sample size estimated was 30 patients per group and was appraised as 35 patients per group to compensate for dropouts during follow-up.

Randomization

A parallel group trial design was used for assigning the patients to the two study groups depending on number of treatment appointments. A random list was generated, 35 patients received treatment in SV (Group 1) and 35 patients in two-visit (Group 2).

Intervention

The principal investigator completed RCT in all cases.

The investigator explained the treatment procedures. Then administered inferior alveolar nerve block using 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine to anesthetize the tooth. After isolation of tooth using a rubber dam, the operator performed access preparation. Canals were negotiated, and apical patency was preserved with a number 10 K-file. The working length was determined with K-file using an apex locator (Root ZX, J Morita corp.) and confirmed by a periapical radiograph. Cleaning and shaping were performed with a hybrid technique using hand K-files (Mani Inc., Japan) and S-one NiTi rotary files (Fanta) for all the teeth. Instrumentation was carried out using 0.04 and 0.06 taper NiTi rotary files along with copious irrigation using 3% NaOCl and saline. Files were employed at a speed of 350 rpm with a slow, gentle in and out movement. 3% Sodium hypochlorite and 17% EDTA were utilized during canal preparation and saline as the final irrigant. Files at least three sizes larger than the initial apical file were used for apical preparation. The canals were dried utilizing sterile absorbent points.

Teeth in Group 1 were obturated at the same visit with gutta-percha cones and Sealapex sealer utilizing the lateral compaction technique, and temporary restoration was placed. A postobturation radiograph was taken. Ibuprofen was prescribed as a rescue medication, and the patients were advised to take it only if they had severe pain after treatment.

In Group 2, calcium hydroxide dressing (RC Cal, Prime Dental Products Pvt. Ltd., India) was placed in the canal as an interappointment medicament. Teeth were sealed with a sterile cotton pellet and a provisional filling material (Prime TMP-RS eugenol free). After 1 week, teeth were obturated utilizing a similar method and materials as used for Group 1. Ibuprofen was prescribed as a rescue medication, and the patients were told to take it only if they had severe pain after treatment.

If a patient in either group took rescue medication within 48 hours after the treatment, he/she was excluded from the study. After 1 week of obturation, teeth were restored by composite restoration (Herculite précis, Kerr, Asia).

Pain assessment

Patients recorded their preoperative pain levels using heft-parker visual analog scale (HP VAS) in the clinician's presence to make sure that they understood the instructions. The patient carried the HP VAS form along with them to record postoperative pain levels at 6-, 12-h, 1, and 2 days' intervals. A telephonic reminder was given to them to note their pain readings and return the form duly filled. The treated teeth were evaluated for tenderness to percussion after 1 week of obturation.

Statistical analysis

The data were tabulated and subsequently analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Intergroup comparison was done with the Student's t-test. For intragroup comparison, the paired t-test was applied at the 0.05 significance level. The frequency and percentage of patients with no pain, mild, moderate, and severe pain were calculated and subjected to the Chi-square test to analyze the incidence of pain in SV and two-visit therapy.

RESULTS

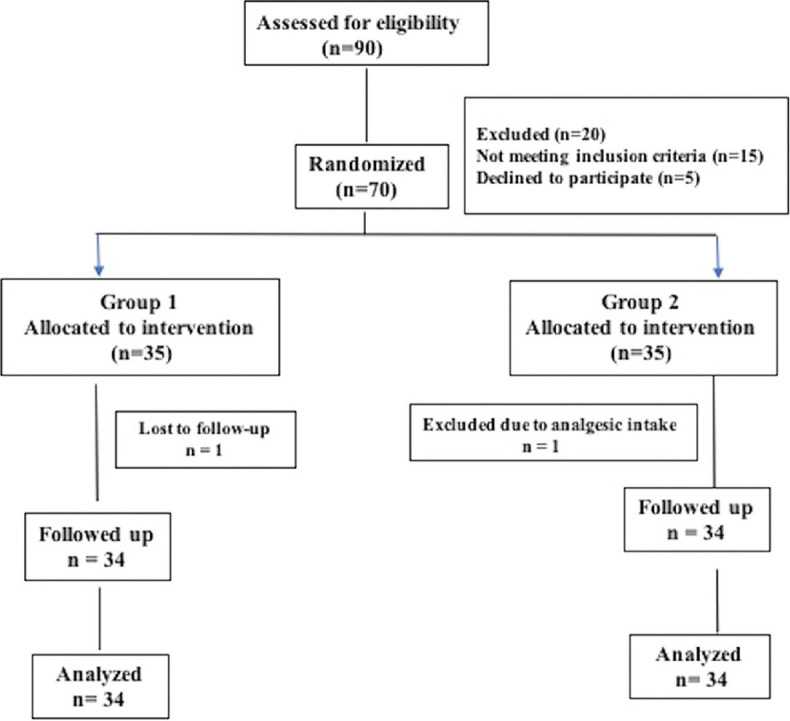

Operator treated 70 patients by RCT, 35 each, in SV and two-visit groups. One patient from the SV group was lost to follow-up. One patient from the MV group took analgesic after the first appointment of the therapy; hence, it was excluded from the study. From both the SV and MV group, 34 patients each were analyzed [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Participants flow diagram

Of the 34 cases in the SV, 17 were female and an equal number of male (50% each). Twenty (58.82%) had vital pulp, whereas 14 (41.17%) had nonvital pulp. In MV group, out of the 34 patients, 23 (67.64%) were female, and 11 (32.36%) were male. Nineteen patients (55.88%) had vital pulp, whereas 15 (44.12%) had nonvital pulpal tooth status.

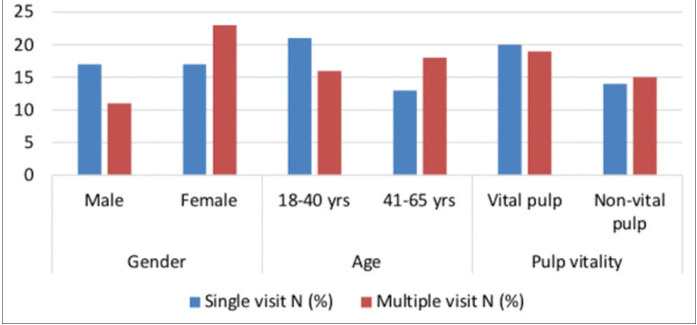

Figure 2 shows the distribution of subjects according to gender, age, and pulpal status. Gender distribution of the SV and MV group differed significantly (P = 0.0395). There was no difference in age (P = 0.0858) and pulp status (P = 0.7297) between the groups.

Figure 2.

Distribution of subjects according to gender, age, and pulpal status

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test result (P > 0.05) exhibited data to be normal. The mean score for pain, standard deviation, and standard error was calculated. The Student's t-test results showed that pain score was significantly higher in MV than SV after 12- (P = 0.039) and 48-h (P = 0.043). The intensity of postobturation pain in both groups steadily decreased over the observation period [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean values of pain between single- and multiple-visit root canal therapy

| Interval | Groups | Mean | SD | SEM | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | SV RCT | 130.97 | 28.212 | 4.838 | −0.110 | 0.912 |

| MV RCT | 131.76 | 31.045 | 5.324 | |||

| 6 h | SV RCT | 93.62 | 25.090 | 4.303 | −1.381 | 0.172 |

| MV RCT | 101.91 | 24.433 | 4.190 | |||

| 12 h | SV RCT | 61.56 | 23.796 | 4.081 | −2.107 | 0.039* |

| MV RCT | 73.62 | 23.391 | 4.012 | |||

| 24 h | SV RCT | 38.18 | 22.242 | 3.814 | −1.217 | 0.228 |

| MV RCT | 45.15 | 24.923 | 4.274 | |||

| 48 h | SV RCT | 8.97 | 13.653 | 2.341 | −2.059 | 0.043* |

| MV RCT | 16.44 | 16.159 | 2.771 |

*P<0.05 (significant). SD: Standard deviation, SEM: Standard error of mean, RCT: Root canal therapy, SV: Single visit, MV: Multiple visits

The prevalence of postobturation pain at 6-, 12-h, 1-, and 2-day intervals was assessed. There was a significant difference (P = 0.005) at the 2-day interval between SV and MV. In SV treatment, 67.64% of participants had no pain, and 32.35% experienced mild pain, whereas, in MV, 44.11% reported no pain, and 55.88% had mild pain [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of prevalence of postoperative pain after single- and multiple-visit root canal therapy

| Time (h) | Group | No pain (%) | Mild (%) | Moderate (%) | Severe (%) | χ 2 P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | SV | 0 | 5 (14.70) | 15 (44.11) | 14 (41.17) | 0.03719* |

| MV | 0 | 4 (11.76) | 9 (26.47) | 21 (61.76) | ||

| 12 | SV | 1 (2.94) | 20 (58.82) | 12 (35.29) | 1 (2.94) | 0.11783 |

| MV | 0 | 16 (47.05) | 13 (38.23) | 5 (14.70) | ||

| 24 | SV | 4 (11.76) | 27 (79.41) | 3 (8.82) | 0 | 0.10829 |

| MV | 2 (5.88) | 25 (73.52) | 7 (20.58) | 0 | ||

| 48 | SV | 23 (67.64) | 11 (32.35) | 0 | 0 | 0.00572* |

| MV | 15 (44.11) | 19 (55.88) | 0 | 0 |

*Significant. SV: Single visit, MV: Multiple visits

None of the treated teeth in both groups was tender to percussion after 7 days of obturation. Hence, no statistic was computed.

DISCUSSION

MV therapy is an established norm in endodontics; however, it has certain disadvantages like inter appointment contamination and flare-ups due to leakage or loss of temporary seal; extended treatment time, leading to patient and operator exhaustion; inability to provide traumatically damaged crowns with esthetic restorations in time; and discontinued treatment leading to failures. These factors contributed to the shift in RCT from MVs to SV endodontic treatment.[7]

Postendodontic pain is one of the most commonly seen complications of endodontic treatment analysis. The occurrence of pain is an outcome of the interaction between physical, chemical, or microbial factors that cause injury to periapical tissues.[8] The rationale for the occurrence of postoperative pain has been clarified.[9] In peripheral sensitization, a bacterial endotoxin LPS may initiate genomic changes in the pulp nociceptors. The expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channels is upregulated in response to nociceptor excitation. In central sensitization, the heightened excitation state of central neurons is triggered by a protracted bombardment of nociceptive impulses from peripheral C fibers. Once established, it becomes less reliant on peripheral input for maintenance. As a result, even if all peripheral variables contributing to hyperalgesia have been eradicated by endodontic treatment, the central mechanism may linger for some time.

In the current study, postoperative pain assessment was done using an HPVAS. This is a bounded scale with values of 0 at one end and 170 at the other end. It was used because of the presence of unequal spacing of words on this scale, which shows a perfect replica of spacing between different pain word descriptors perceived by the patient. It is considered an endorsed and reliable ratio scale instrument for measuring human pain intensity and unpleasantness when properly designed and administered.[10]

In the existent study, pain score in MV was significantly higher than the SV after 12- (P = 0.039) and 48-h (P = 0.043) time intervals. 32.35% of participants had postoperative pain after an SV compared with 55.88% of MV treatment. The lower prevalence of postoperative pain in one-visit RCT might be ascribed to immediate obturation, thereby to evade the passage of medications, repeated instrumentation, and irrigation.

The present study's result agrees with those of Roane et al.,[11] Albashaireh et al.,[12] Patil et al.,[13] Singh et al.[4] whereas Dhyani et al.[14] and Soltanoff[15] reported contrary findings to those of the present study. Soltanoff rationalized that if severe preoperative inflammation exists, there would be an inclination to expect a significant increase in postoperative pain after an SV procedure. Anjaneyulu and Nivedhitha[16] in a systematic review, reported that calcium hydroxide as an intra-canal medicament was impertinent to the incidence and severity of posttreatment pain.

In the present study, there is a significant difference (P = 0.001) in the mean pain score of males and females. Women tend to pursue and receive treatment more voluntarily, as symptoms are readily perceived as signs of disease by females. Females agonize more commonly from psychosomatic illnesses, and that emotional factors govern their pain.[17] Biological differences between genders may clarify increased pain prevalence in women.[18]

In the current study, pain experience after MV was higher in older patients than younger age group; however, pain intensity was not different. Postoperative pain is higher in elderly patients than in young patients because of less pain tolerance, less blood flow, and delayed healing.[19] Previous studies[16,20] have shown that preoperative pain increases the probability of postoperative pain. Hyperalgesia and allodynia may persist even after completing the dental treatment in a symptomatic tooth. Patients with preoperative pain are more likely to experience postendodontic pain since it is what they expect.[21]

In the existent study, vital teeth exhibited a higher mean pain score than the nonvital teeth in both groups. The injury of peri-apical tissue during endodontic therapy in teeth with vital pulp fosters more intensive secretion of an inflammatory mediator such as prostaglandin, leukotrienes which also are pain-mediators.[21] Clem,[22] Calhoun and Landers[23] found that pain on percussion (POP) is more common following the treatment of teeth with vital pulp.

In the present study, mandibular molars were chosen as test teeth. Selecting a single tooth type helped standardize the analysis by eliminating the tooth type and the arch's confounding effect. Tooth location may affect an endodontically treated tooth's postoperative pain tolerance because of its particular function and nature of the masticatory forces.[24] Posterior teeth are more susceptible to POP. This susceptibility may be attributed to the complex morphology and greater number of root canals that are more challenging to debride thoroughly and increase the potential peri-apical pain foci.

In the present study, a 10 K-file was used as the patency file. Smaller files cause less transportation and extrude less contaminated debris. According to Seltzer,[8] the release of inflammatory mediators due to apical extrusion of contaminated debris is the main etiological factor for periapical inflammation and postoperative pain. Arora et al.[25] and Yaylali et al.[26] reported less postoperative pain by retaining apical patency.

Instead of focusing on the number of appointments, it would be best to focus on treating the disease - apical periodontitis. As clinicians, we cannot give in to pressures to provide “convenient” care. Patients always want it quickly, but we must consider each case's biological demands and treat them accordingly. Long-term tooth loss is overwhelmingly due to structural failure or caries, not endodontic failure. We can improve our outcomes by starting with structurally sound teeth, maintaining as much tooth structure as possible during our procedures, and restoring them well. Those are things over which we have some degree of control, unlike biology.

There are many factors involved to “control” variables in a study of this undertaking. Variables such as patient genetics, health conditions, hygiene practices, quality of coronal restoration, and operator error, to name a few. The present study's limitations include a smaller sample size and noninclusion of variations between single- and multiple-rooted teeth. Further studies should be carried out in endodontic clinical settings with a larger sample and longer follow-up periods.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitation of the study, the following conclusions are drawn:

The short-term postoperative pain incidence was higher in two-visit than SV RCT of mandibular first molar teeth

In both SV and MV root canal treatment, postobturation pain intensity reduced over the 48 h observation period

Teeth were not tender to percussion after 1 week, irrespective of SV or MV treatment.

MV RCT with an interappointment dressing of calcium hydroxide does not seem to influence pain outcome. SV RCT is an effective approach to manage stipulated cases, particularly in communities where patients default after the first visit at which pain is relieved.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hitkarini Dental College for infrastructure support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manfredi M, Figini L, Gagliani M, Lodi G. Single versus multiple visits for endodontic treatment of permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD005296. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005296.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Mubarak AH, Abu-bakr NH, Ibrahim YE. Postoperative pain in multiple-visit and single-visit root canal treatment. J Endod. 2010;36:36–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alomaym MA, Aldohan MF, Alharbi MJ, Alharbi NA. Single versus multiple sitting endodontic treatment: Incidence of postoperative pain – A randomized controlled trial. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2019;9:172–7. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_327_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Konark, Kumar A, Nazeer J, Singh R, Singh S. Incidence of postoperative flare-ups after single-visit and multiple-visit endodontic therapy in permanent teeth. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2020;38:79–83. doi: 10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_354_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prashanth MB, Tavane PN, Abraham S, Chacko L. Comparative evaluation of pain, tenderness and swelling followed by radiographic evaluation of periapical changes at various intervals of time following single and multiple visit endodontic therapy: An in vivo study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011;12:187–91. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong AW, Tsang CS, Zhang S, Li KY, Zhang C, Chu CH. Treatment outcomes of single-visit versus multiple-visit non-surgical endodontic therapy: A randomised clinical trial. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:162. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashkenaz PJ. One-visit endodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1984;28:853–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seltzer S, Naidorf IJ. Flare-ups in endodontics: I. Etiological factors. 1985. J Endod. 2004;30:476–81. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu C, Abbott P. Pulp microenvironment and mechanisms of pain arising from the dental pulp: From an endodontic perspective. Aust Endod J. 2018;44:82–98. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Garg A. Comparison of the pain levels of computer controlled and conventional anesthesia techniques in supraperiosteal injections: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:740–3. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2012.715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roane JB, Dryden JA, Grimes EW. Incidence of postoperative pain after single- and multiple-visit endodontic procedures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:68–72. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albashaireh ZS, Alnegrish AS. Postobturation pain after single- and multiple-visit endodontic therapy. A prospective study. J Dent. 1998;26:227–32. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patil AA, Joshi SB, Bhagwat SV, Patil SA. Incidence of postoperative pain after single visit and two visit root canal therapy: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC09–12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16465.7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhyani VK, Chhabra S, Sharma VK, Dhyani A. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the incidence of postoperative pain and flare-ups in single and multiple visits root canal treatment. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soltanoff W. A comparative study of the single-visit and the multiple-visit edodontic procedure. J Endod. 1978;4:278–81. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(78)80144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anjaneyulu K, Nivedhitha MS. Influence of calcium hydroxide on the post-treatment pain in Endodontics: A systematic review. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17:200–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.131775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng YL, Glennon JP, Setchell DJ, Gulabivala K. Prevalence of and factors affecting post-obturation pain in patients undergoing root canal treatment. Int Endod J. 2004;37:381–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan JL, Jureidini B, Hodges JS, Baisden M, Swift JQ, Bowles WR. Gender differences in analgesia for endodontic pain. J Endod. 2008;34:552–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali SG, Mulay S, Palekar A, Sejpal D, Joshi A, Gufran H. Prevalence of and factors affecting post-obturation pain following single visit root canal treatment in Indian population: A prospective, randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:459–63. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.107440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shresha R, Shrestha D, Kayastha R. Post-operative pain and associated factors in patients undergoing single visit root canal treatment on teeth with vital pulp. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2018;16:220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iqbal M, Kurtz E, Kohli M. Incidence and factors related to flare-ups in a graduate endodontic programme. Int Endod J. 2009;42:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clem WH. Posttreatment endodontic pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970;81:1166–70. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1970.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calhoun RL, Landers RR. One-appointment endodontic therapy: A nationwide survey of endodontists. J Endod. 1982;8:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(82)80315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arias A, de la Macorra JC, Hidalgo JJ, Azabal M. Predictive models of pain following root canal treatment: A prospective clinical study. Int Endod J. 2013;46:784–93. doi: 10.1111/iej.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora M, Sangwan P, Tewari S, Duhan J. Effect of maintaining apical patency on endodontic pain in posterior teeth with pulp necrosis and apical periodontitis: A randomized controlled trial. Int Endod J. 2016;49:317–24. doi: 10.1111/iej.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaylali IE, Kurnaz S, Tunca YM. Maintaining apical patency does not increase postoperative pain in molars with necrotic pulp and apical periodontitis: A randomised controlled trial. J Endod. 2018;44:335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]