ABSTRACT

Background:

Parental dental fear and anxiety (DFA) is an important factor, which has an impact on adolescence receiving dental treatment and maintenance of their oral health. It is necessary to recognize and know how parental DFA affects the dental treatment of children and adolescents.

Aim:

This narrative review was planned with the objective of evaluating parental DFA influence on adolescent dental treatment.

Materials and Methods:

A broad search of literature published between 2005 and 2021 from electronic databases through Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar was performed. We included the studies in which parental dental anxiety was a major criterion affecting different dental health conditions. Articles referring to adolescents facing different oral health problems were also included. This narrative review included 12 articles of which 8 cross-sectional studies, 3 longitudinal studies, and 1 descriptive study, all of which met the inclusion criteria and the specified age group of adolescents ranging between 10 and 19 years.

Results:

After screening 83 abstracts, 12 articles were selected, which included all the inclusion criteria. In this study, we found that parental DFA showed a positive association with their adolescent’s DFA, which hinders the dental treatment received.

Conclusion:

Parental DFA influences the adolescent behavior and can impact the seeking of dental treatment. Hence, it is important to address parental DFA prior to the intervention and treatment. An appropriate address will facilitate in reducing or eliminating DFA in adolescents.

KEYWORDS: Adolescent, dental anxiety, dental fear, parent

INTRODUCTION

Dental anxiety is a negative state of mind of a dental patient, which is shown to be excessive and unreasonable.[1] Dental fear is a normal emotional response to particularly alarming stimuli in situations related to dental treatment.[1] Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) are often used together to describe different types of fear experienced in the dental environment.[2] American Academy of Pediatrics divides adolescents into three age groups: early 11–14 years, middle 15–17 years, and late 18–21 years.[3] Five specific pathways for DFA were seen in adolescent dental patients. One of which being the parental pathway plays an important role in the transmission of fear hindering their child’s dental treatment.[4] Parental DFA is usually an excessive perturbing of the things that could go wrong in child’s oral health and is an important factor that has an impact on adolescents receiving dental treatment and maintenance of their oral health. It is necessary to recognize and know how parental DFA affects the dental treatment of adolescents. Thus, this review aimed at evaluating the parental influence of DFA on dental treatment of adolescents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DATA EXTRACTION AND LITERATURE SEARCH STRATEGY

A broad search of literature published between 2005 and 2021 from electronic databases through Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science was performed. These studies were conducted in different countries as mentioned in Table 1. This review article includes eight cross-sectional studies, three longitudinal studies, and one descriptive study. The age group of children included ranged from 10 to 19 years.

Table 1.

Summary study design, data collection, dental fear and anxiety assessment scales used analysis, and interpretation of reviewed articles

| Title and reference number | Study design | Data collection | Terms used | Methods used to assess DFA | Validation of DFA scales used | Analysis and interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. The effect of orthodontic extra oral appliances on depression and the anxiety levels of patients and parents | Cross-sectional | 50 (control group) and 45 (treatment group) 12–17 years. Turkey |

Dental anxiety and depression | 1. BAI and BDI scale. | Both validated | Patients and their parent’s anxiety level have a negative impact due to extra oral appliance |

| 13. Does orthodontic treatment affect patients’ and parents’ anxiety levels? | Cross-sectional | 40 (control group) and 43 (Treatment group) 14 years. Turkey |

Anxiety, state and trait anxiety | 1.STAI 2. Personal information form | Not specified | Trait anxiety levels between parents and in the children were same before the start of treatment and after 1 year it remained unchanged in parents, whereas in children it reduced. |

| 6. Impact of traumatic dental injuries among adolescents on family’s quality of life: a population-based study | Cross-sectional | 1122, 11–14 years. Brazil |

Parental emotion | 1.Brazilian version of FIS | Validated | Negative impact on parental anxiety emotion, and family conflict of families of adolescents with severe TDI.§§ |

| 9. Dental fear association between mothers and adolescents-a longitudinal study. | Longitudinal study | 212 (12 years), 195 (15 years), and 182 (18 years). Hong Kong |

Dental fear and dental anxiety | 1.MDAS | Validated | Adolescent’s and mother’s dental fear is associated at 12 years and 18 years of age and not in 15 years. |

| 15. Emotional contagion of dental fear to children: the fathers’ mediating role in parental transfer of fear | Cross-sectional | 183, 7–12 years. Spain |

Dental fear and dental anxiety | 1.Questionnaire-based survey (children fear survey schedule). Parents filled a version of the same scale. | Not specified | Among family members, emotional transfer of dental fear seen Prominent role of father’s in regarding the transfer of dental fear from parents to children. |

| 10. Transmission of dental fear from parent to adolescent in an Appalachian sample in the USA. | Cross-sectional | 515, 11–17 years. USA |

Dental fear, dental anxiety, and fear of pain | 1.DFS§ 2.Fear of Pain. General fearfulness about pain was assessed with the FPQ-9 |

Both validated | Intergenerational transmission of dental fear seen from parents to adolescent’s Father’s predicted dental fear and anxiety of adolescent’s |

| 11. Dental fear and anxiety in older children: an association with parental dental anxiety and effective pain coping strategies | Descriptive study | 114, 7–15 years. Mosar Bosania Herzegovina |

. Dental fear and dental anxiety | 1.CDAS––both parents and children 2.Sociodemographic questionnaire––both parents and children |

All validated | Coexistence of DFA¦¦ in parents and children |

| 16. Can parents and children evaluate each other’s dental fear? | Longitudinal study | Pori (1691), Rauma (807)/ Finland 11–16 years |

Dental fear | 1.Questionnaire; whether child and parent have dental fear 5-point Likert scale was used. | Not specified | Parents with dental fear assumed their child to be fearful irrespective of their child’s actual fear. |

| 12. Fear of dental pain in Italian children: child personality traits and parental dental fear | Cross-sectional | 104 5–14 years. Italy |

Dental anxiety and dental fear | 1.Italian version of the FPQ 2.STAI Y1 and Y2 3.BDI-II |

All validated | Significant positive correlation between parent and children’s dental fear |

| 14. A longitudinal study of changes and associations in dental fear in parent/adolescent dyads | Longitudinal study | 1691, 11–12, 15–16 years. City of Pori |

Dental fear | 1.Single question using five-question alternatives. | Validated | A positive association between adolescent and parental dental fear in early adolescence but only among girls in middle adolescence. |

| 7. Children’s dental fear and anxiety: exploring family related factors. | Cross-sectional | 405 9–13 years. Hong Kong |

Dental anxiety and dental fear |

1.CDAS | Validated | Children’s dental fear anxiety is not affected significantly by their parent’s dental fear anxiety or parenting style. |

| 8. The relationship between dental anxiety in children, adolescents and their parents at dental environment | Cross-sectional | 100, 8–17 years. Brazil |

Dental anxiety | 1.CDAS 2. STAI |

Validated | A positive relation between trait and dental anxiety scores (8–11 years) among parents and children No significant association between anxiety levels of parents and adolescence (12–17 years) |

DFA = dental fear and anxiety, BAI = beck anxiety inventory, BDI = beck depression inventory, STAI = state and trait anxiety inventory, FIS = family impact scale, MDAS = modified dental anxiety scale, DFS = dental fear survey, FPQ-9 = fear of pain questionnaire-9, CDAS = Corah dental anxiety scale, FPQ = fear of pain questionnaire, TDI = traumatic dental injuries

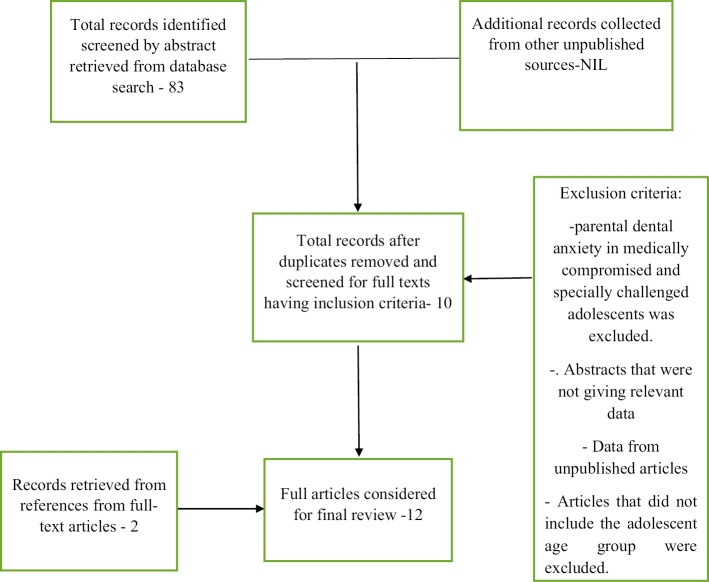

The search was carried out using the following keywords: dental anxiety, parental dental anxiety, adolescent, and dental treatment. The terms used to formulate the search strategies were parent OR mother OR father AND dental fear OR dental anxiety AND adolescent AND dental treatment. Data extracted were independently reviewed and disagreements were solved by discussion. A flowchart representing the method of article selection for the review is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart representing the method of article selection

INCLUSION CRITERIA

We included the studies in which parental dental anxiety was a major criterion affecting different dental health conditions. Articles referring to adolescents (10–19 years) facing different oral health problems were also included in the study.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Abstracts that were not giving relevant data, data from unpublished articles, parental dental anxiety in medically compromised and specially challenged adolescents, and articles that did not include the adolescent age group were excluded from the study.

RESULTS

Approximately 83 publications were found related. Screening identified 10 articles that fulfilled the criteria of inclusion; full-text versions were retrieved and their references were screened for further relevant articles. Checking the subreference list, another two relevant articles were found. Thus, 12 articles were considered for this review that met the final inclusion criteria. Of 12 articles reviewed, 8 studies[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] used validated assessment scales as mentioned by authors for measuring parental DFA. The authors have not specified the validation of assessment scales used for the other four studies.[13,14,15,16] The various DFA assessment scales used in the reviewed articles are mentioned in Table 2. Summary study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of reviewed articles are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 2.

Tabular representation of dental fear and anxiety assessment scales used

| CDAS | 1969––published by Corah et al.[38] | • Contained four multiple-choice questions[38] |

|---|---|---|

| • Found to be useful, valid, and reliable scale.[38] | ||

| MDAS | 1995––Humphris et al.[39] | • It is a modified version of CDAS[39] • An additional question on anxiety regarding oral injections was included[39] |

| • A simplified and new answering scheme was used | ||

| • High reliability and validity confirmed[39,40] | ||

| FPQ-9 | 2012––first nine-item questionnaire used (in its unpublished format) by Parr et al.[41] | • A shortened version of Fear of Pain QuestionnaireⅢ[42] • Valid and reliable measure to assess dental fear and anxiety with good psychometric properties.[42] |

| DFS | 1973––Kleinknecht et al.[42] | • Measures both dental fear and anxiety • 20-item self-report scale |

| • Three subscale scores: (a) physiological arousal fear, (b) fear of specific dental stimuli, and (c) avoidance/anticipatory[42] | ||

| FIS | 2002––Jokovic et al.; 2002––Goursand et al.[43] | • 14-item questions • Four subscales: parental activity, parental emotions, family conflict, and financial burden |

| • Good reliability, validity, and psychometric properties[43] | ||

| BAI | 1988––Beck et al. | • 21-item questionnaire |

| • Differentiates between anxiety and depression[44] • Valid and reliable measure.[45] |

||

| BDI | 1961––Beck et al.[46] | • 21-item questionnaire that quantitatively assesses the intensity of depression.[46] |

| • Varying degree of depression is differentiated.[46] | ||

| • Valid and reliable measure.[46,47] | ||

| Fear of dental pain questionnaire | 2003––van Wijk et al.[48] | • Measures both general fear and dental fear. |

| • Provides dental fear equivalent to FPQⅢ | ||

| • Valid, reliable with high internal concistency.[48] | ||

| STAI | 1970––(STAI-X) Spielberger et al.[45] | • 40-item questionnaire––20 items for each subscale[49] |

| Revised in 1983––(STAI –Y)[49] |

DFA = dental fear and anxiety, BAI = beck anxiety inventory, BDI = beck depression inventory, STAI = state and trait anxiety inventory, FIS = family impact scale, MDAS = modified dental anxiety scale, DFS = dental fear survey, FPQ-9 = fear of pain questionnaire-9, CDAS = Corah dental anxiety scale, FPQ = fear of pain questionnaire

DISCUSSION

Dental anxiety being primarily a negative parental factor was found to affect children from assessing regular dental care. Among the reviewed articles based on the outcome, we found that three articles explained about a relationship between parental DFA and adolescent dental treatment,[6,7,13] and the remaining nine articles explained about the correlation between parental DFA scores with adolescent DFA scores.[6,8,9,10,11,13,14,15,16] No significant association was observed between parental DFA and adolescent DFA scores in two of the studies,[7,8] whereas two studies showed positive association only during early adolescence.[9,14] Other five studies showed a significant positive correlation of parental DFA with their children’s dental anxiety,[10,11,12,15,16] of which three studies also suggested fathers as mediating role in transmission of DFA to their children.[10,11,15]

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTAL DENTAL FEAR AND ANXIETY AND ADOLESCENT DENTAL TREATMENT

Adolescent dental treatment utilization mainly depends on parental/caretaker’s decision-making and their dental care obtaining habits. In childhood and even adolescence, this becomes very crucial for the development of good oral health behavior like regular visits to the dentist and preventive dental care.[17] Another postulated process is “social learning” wherein, media, friends, and relatives portray dentists in negative light or image leading to formation of DFA. These processes of information transmission and vicarious experience lead to negative portrayal of dentists and pessimistic expectations about the dentist’s role. All these predispose to DFA.[18] The absence of anxiety among parents would have a positive influence on a child.[19] Parental dental anxiety along with family income, economic stability, parental oral health literacy, and oral health practices is found to be a few factors that affect adolescent’s oral health-related quality of life (QOL).[20,21,22]

Dental anxiety being primarily a negative parental factor was found to affect children from accessing regular dental care, whereas parental self-dental utilization being a positive parental factor showed a positive impact on a child’s dental utilization.[23] Parents with higher anxiety levels were found to start brushing their children’s teeth at an earlier age; hence, a significant correlation was found between parent’s anxiety levels and the age at which the child starts to brush.[24] Dental health status of children was found to be better with more a positive attitude of parents toward dentistry.[25]

Among the articles reviewed, two articles were found to have parental DFA during fixed orthodontic treatment of the adolescents which included the use of extraoral appliances. These two studies used different anxiety measurement scales for assessing parental DFA before and during the treatment procedures.[5,13] Poorer QOL is seen in families of adolescents with malocclusion as compared with the families of adolescents without any occlusal variation; the impact may have effects on parental or guardian’s emotions.[26] Both of the studies assessed state and trait dental anxiety of parents (STAI scale). State anxiety is transient, fluctuates, and varies in intensity. Trait anxiety is a personality trait; it is stable with time.[27,28] The result showed that parent’s trait anxiety levels did not change during orthodontic treatment.[5,13] State anxiety was found to be within normal range and changed according to intensity of pressure.[13] There was an incidence of high levels of state anxiety and depression in both parents and patients under treatment with extra oral orthodontic appliances after 1 year of active treatment. Among patients waiting for orthodontic treatment and among their parents no statistically significant differences were noted in their trait anxiety levels.[5] The extra oral appliances had a negative effect on patient’s and parent’s anxiety levels which might indirectly affect the ongoing dental treatment. It was therefore recommended for clinicians to have alternate treatment modalities in mind to address this challenge.[5]

Apart from orthodontic treatment, adolescents are also found commonly with traumatic dental injuries (TDIs) involving dentine/pulp or fracture of the root. A family’s QOL in such conditions was assessed using the family impact scale (FIS). This scale had four subscales, in which parental emotion was one of the subscales assessed. Parental emotion had a significant negative impact on the severity of TDI and severe untreated TDI of an adolescent can be a source of family distress.[6,29,30]

EVIDENCE OF ASSOCIATION OF DENTAL FEAR AND ANXIETY BETWEEN PARENTS AND THEIR ADOLESCENTS

Previous studies have shown that parents exhibit an influence on their children’s DFA through modeling and information.[31] The DFA experienced in childhood may lead into adulthood causing a predictor for dental treatment avoidance in adulthood.[32,33]

Among the reviewed articles, we found a correlation between the parental dental DFA scores with their adolescent’s DFA scores. Parent’s DFA and children’s DFA were assessed using the same dental anxiety measuring scale in nine of the studies,[6,8,9,10,11,13,14,15,16] and three studies[5,7,12] used different scales to measure anxiety levels in parents and children’s.

Two of the studies showed no significant association between the anxiety level of adolescents and that of their parents.[7,8] One of the studies suggested that when a child reached adolescence, parental DFA does not directly contribute to child DFA. Other factors such as the presence of a sibling and family structure (single-parent family, nuclear) are found to play a significant role.[7] Lending support to the former findings, there was no relation between anxiety levels of adolescents (12–17 years) and that of their parents, whereas in the same study a positive association was found when the child is 8–11 years of age.[8]

Two studies suggested a positive association in early adolescence.[9,14] In one of these two studies, mother’s and adolescents dental fear scores had a significant association at the age of 12 years and 18 years in given treatment scenarios such as “feeling about having their teeth scraped and polished, having teeth drilled and having an injection in gum,” whereas there was no significant association between dental fear scores of mother’s and adolescence at 15 years of age.[9] In another study reviewed, in early adolescence (11–12 years), there was a statistically significant association between parental and adolescent dental fear but in mid-adolescence (15–16 years) there was only an association with parental dental fear with their daughters.[14] It was found in the Finnish population, by eliminating dental fear among 30 years and elderly population, 41% of irregular attendees could become regular attenders.[34] In contrast, other five studies showed a significant positive correlation of parental DFA with their children’s dental anxiety.[10,11,12,15,16] Fearful parents of adolescents of age (11–16 years) assumed that their child had fear irrespective of whether the child had fear or not.[16] Three of these studies, where parental DFA was assessed in both the parents, suggested that the father also has a mediating role in the transmission of DFA to the children of age group 11–17 years,[10] 7–15 years,[11] and 7–12 years,[15] respectively. Father’s DFA is one of the best predictors of adolescence DFA[10,35] and it is also found that child’s dental anxiety is best predicted by the parent’s fear of pain.[12] Previous studies have suggested that children experience fear and anxiety in their early life due to a lack of cognitive ability without having a clear perception of fearful situation and have been influenced by their parent’s fear and anxiety.[36] It is still unclear of the association of DFA between parents and late adolescents.[9]

It was found that limited studies were found in the area of adolescent oral health. In the available literature, definite assessment methods were not used to assess the anxiety levels among parents. Furthermore, studies focused on late adolescence are indicated to establish the changes in oral health due to parental DFA.

Adolescence is the transitional phase between childhood and adulthood and is a crucial period where they develop decision-making and independence; this has an impact on dental treatment-seeking behavior. The influence of parental dental anxiety might worsen the scenario. Parental DFA is seen to have a direct impact on the treatment itself.[5,6,20] Previously reviewed articles show a strong association of parental DFA and child’s DFA below 8 years of age.[37] In this study, we found parental DFA showed a positive association with their adolescent’s DFA, which thus hinders their dental treatment. There is a need to give attention to psychological parameters before and during the treatment of both parents and adolescents. Therefore, identifying parental dental anxiety prior to the treatment and intervention helps to reduce or eliminate DFA in children and further improves their dental treatment utilization.

This study adds value in sensitizing dental professionals toward addressing parental concerns while treating adolescents and recommendations for appropriate implementations in teaching curricula and policies regarding the same.

There is more potential to understand the background of parental DFA in single parents and in mother and father alone and also the factors that made them vulnerable.

Parental education/counselling regarding various dental treatment procedures using appropriate methods such as focus group discussion will help to reduce DFA among the parental populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Health Sciences Library, Manipal Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Udupi, Karnataka, India and Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College and Hospital, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Udupi, Karnataka, India.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

This study was self-funded.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Idea and conceptualization: Ramprasad Vasthare. Literature search: Thrisha Hegde, Bhavyashri P. Manuscript writing: Thrisha Hegde, Bhavyashri P, Ramprasad Vasthare, Karthik M, Ravindra Munoli. Editing of the review: Ramprasad Vasthare, Thrisha Hegde, Bhavyashri P, Karthik M, Ravindra Munoli. Intellectual inputs: Ramprasad Vasthare, Ravindra Munoli, Karthik M.

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

Not applicable as this was a narrative review.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT

Not applicable.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data of literature search is available on appropriate request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shim YS, Kim AH, Jeon EY, An SY. Dental fear & anxiety and dental pain in children and adolescents: A systemic review. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2015;15:53–61. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2015.15.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behaviour management problems in children and adolescents: A review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Paediatrics. Adolescent Sexual Health: Stages of Adolescent Development. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/adolescent-sexual-health/Pages/Stages-of-Adolescent-Development.aspx .

- 4.Carter AE, Carter G, Boschen M, AlShwaimi E, George R. Pathways of fear and anxiety in dentistry: A review. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:642–53. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i11.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topcuoglu T, Yildirim O, Birlik M, Sokucu O, Semiz M. The effect of orthodontic extraoral appliances on depression and the anxiety levels of patients and parents. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:81–5. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.122850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendo CB, Paiva SM, Abreu MH, Figueiredo LD, Vale MP. Impact of traumatic dental injuries among adolescents on family’s quality of life: A population-based study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;24:387–96. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu L, Gao X. Children’s dental fear and anxiety: Exploring family related factors. Bmc Oral Health. 2018;18:100. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assuncão CM, Losso EM, Andreatini R, de Menezes JV. The relationship between dental anxiety in children, adolescents and their parents at dental environment. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2013;31:175–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.117977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong HM, Zhang YY, Perfecto A, McGrath CPJ. Dental fear association between mothers and adolescents: A longitudinal study. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9154. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeil DW, Randall CL, Cohen LL, Crout RJ, Weyant RJ, Neiswanger K, et al. Transmission of dental fear from parent to adolescent in an Appalachian sample in the USA. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29:720–7. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coric A, Banozic A, Klaric M, Vukojevic K, Puljak L. Dental fear and anxiety in older children: An association with parental dental anxiety and effective pain coping strategies. J Pain Res. 2014;7:515–21. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S67692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Alessandro G, Alkhamis N, Mattarozzi K, Mazzetti M, Piana G. Fear of dental pain in Italian children: Child personality traits and parental dental fear. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76:179–83. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sari Z, Uysal T, Karaman AI, Sargin N, Ure O. Does orthodontic treatment affect patients’ and parents’ anxiety levels? Eur J Orthod. 2005;27:155–9. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luoto A, Tolvanen M, Pohjola V, Rantavuori K, Karlsson L, Lahti S. A longitudinal study of changes and associations in dental fear in parent/adolescent dyads. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27:506–13. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara A, Crego A, Romero-Maroto M. Emotional contagion of dental fear to children: The fathers’ mediating role in parental transfer of fear. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22:324–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luoto A, Tolvanen M, Rantavuori K, Pohjola V, Lahti S. Can parents and children evaluate each other’s dental fear? Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:254–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heima M, Heaton L, Gunzler D, Morris N. A mediation analysis study: The influence of mothers’ dental anxiety on children’s dental utilization among low-income African Americans. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45:506–11. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry JH, McCann D. Dentistry’s public image: Does it need a boost? J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;118:686–9, 691-2. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1989.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Versloot J, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J, Martens LC. Children’s coping with pain during dental care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:456–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen-Carneiro F, Souza-Santos R, Rebelo MA. Quality of life related to oral health: Contribution from social factors. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:1007–15. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011000700033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar S, Kroon J, Lalloo R. A systematic review of the impact of parental socio-economic status and home environment characteristics on children’s oral health related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:41. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang B, Wong HM, Perfecto AP, McGrath CPJ. The association of socio-economic status, dental anxiety, and behavioral and clinical variables with adolescents’ oral health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:2455–64. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooley M, Skouteris H, Boganin C, Satur J, Kilpatrick N. Parental influence and the development of dental caries in children aged 0–6 years: A systematic review of the literature. J Dent. 2012;40:873–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gavic L, Tadin A, Mihanovic I, Gorseta K, Cigic L. The role of parental anxiety, depression, and psychological stress level on the development of early-childhood caries in children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28:616–23. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chhabra N, Chhabra A. Parental knowledge, attitudes and cultural beliefs regarding oral health and dental care of preschool children in an Indian population: A quantitative study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:76–82. doi: 10.1007/BF03262848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abreu LG, Corradi-Dias L, Dos Santos TR, Melgaço CA, Lages EMB, Paiva SM. Quality of life of families of adolescents undergoing fixed orthodontic appliance therapy: Evaluation of a cohort of parents/guardians of treated and untreated individuals. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30:634–41. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caumo W, Broenstrub JC, Fialho L, Petry SM, Brathwait O, Bandeira D, et al. Risk factors for postoperative anxiety in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:782–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papay JP, Spielberger CD. Assessment of anxiety and achievement in kindergarten and first- and second-grade children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1986;14:279–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00915446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francisco SS, Filho FJ, Pinheiro ET, Murrer RD, de Jesus Soares A. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries and associated factors among Brazilian schoolchildren. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11:31–8. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traebert J, Bittencourt DD, Peres KG, Peres MA, de Lacerda JT, Marcenes W. Aetiology and rates of treatment of traumatic dental injuries among 12-year-old school children in a town in southern brazil. Dent Traumatol. 2006;22:173–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rachman S. The conditioning theory of fear-acquisition: A critical examination. Behav Res Ther. 1977;15:375–87. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(77)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crocombe LA, Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Brennan DS, Slade GD, Poulton R. Dental visiting trajectory patterns and their antecedents. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milgrom P, Weinstein P. Dental fears in general practice: New guidelines for assessment and treatment. Int Dent J. 1993;43:288–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pohjola V, Lahti S, Vehkalahti MM, Tolvanen M, Hausen H. Association between dental fear and dental attendance among adults in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2007;65:224–30. doi: 10.1080/00016350701373558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rantavuori K, Lahti S, Hausen H, Seppä L, Kärkkäinen S. Dental fear and oral health and family characteristics of Finnish children. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:207–13. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laki K, Beslot-Neveu A, Wolikow M, Davit-Béal T. [Child dental care: What’s about parental presence?] Arch Pediatr. 2010;17:1617–24. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Themessl-Huber M, Freeman R, Humphris G, MacGillivray S, Terzi N. Empirical evidence of the relationship between parental and child dental fear: A structured review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:83–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corah NL, Gale EN, Illig SJ. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97:816–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The modified dental anxiety scale: Validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Humphris GM, Freeman R, Campbell J, Tuutti H, D’Souza V. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the modified dental anxiety scale. Int Dent J. 2000;50:367–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parr JJ, Borsa PA, Fillingim RB, Tillman MD, Manini TM, Gregory CM, et al. Pain-related fear and catastrophizing predict pain intensity and disability independently using an induced muscle injury model. J Pain. 2012;13:370–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kleinknecht RA, Klepac RK, Alexander LD. Origins and characteristics of fear of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1973;86:842–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1973.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goursand D, Paiva SM, Zarzar PM, Pordeus IA, Allison PJ. Family impact scale (FIS): Psychometric properties of the Brazilian Portuguese language version. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spielberger CD, Goursuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory

- 46.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson BE, Kelley L. Concurrent validity of the beck depression inventory as a measure of depression. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:929–30. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Wijk AJ, Hoogstraten J. The fear of dental pain questionnaire: Construction and validity. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:12–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI), beck anxiety inventory (BAI), and hospital anxiety and depression scale-anxiety (HADS-A) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:S467–72. doi: 10.1002/acr.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data of literature search is available on appropriate request to the corresponding author.