Abstract

The availability of inorganic phosphate (Pi) for ATP synthesis is thought to limit photosynthesis at elevated [CO2] when Pi regeneration via sucrose or starch synthesis is limited. We report here another mechanism for the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis caused by insufficient capacity of chloroplast triose phosphate isomerase (cpTPI). In cpTPI-antisense transgenic rice (Oryza sativa) plants with 55%–86% reductions in cpTPI content, CO2 sensitivity of the rate of CO2 assimilation (A) decreased and even reversed at elevated [CO2]. The pool sizes of the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolites from pentose phosphates to 3-phosphoglycerate increased at elevated [CO2], whereas those of ATP decreased. These phenomena are similar to the typical symptoms of Pi-limited photosynthesis, suggesting sufficient capacity of cpTPI is necessary to prevent the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis and that cpTPI content moderately affects photosynthetic capacity at elevated [CO2]. As there tended to be slight variations in the amounts of total leaf-N depending on the genotypes, relationships between A and the amounts of cpTPI were examined after these parameters were expressed per unit amount of total leaf-N (A/N and cpTPI/N, respectively). A/N at elevated [CO2] decreased linearly as cpTPI/N decreased before A/N sharply decreased, owing to further decreases in cpTPI/N. Within this linear range, decreases in cpTPI/N by 80% led to decreases up to 27% in A/N at elevated [CO2]. Thus, cpTPI function is crucial for photosynthesis at elevated [CO2].

Suppression of chloroplast triose phosphate isomerase suppresses photosynthesis at elevated [CO2] with the typical symptoms of photosynthesis limited by Pi availability for ATP synthesis.

Introduction

As improving photosynthesis is thought to be an effective means for improving plant productivity (Zhu et al., 2010; Evans, 2013; Simkin et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2020), the molecular mechanisms that limit photosynthetic capacity need to be revealed and have been studied extensively. CO2 assimilation is carried out by the Calvin–Benson cycle, which consists of 11 enzymes and produces carbohydrates from atmospheric CO2 using NADPH and ATP supplied by photochemical reactions (Calvin, 1962; Heldt and Piechulla, 2011). The rate of CO2 assimilation (A) is also closely related to the production of sucrose or starch, which are end products of photosynthesis, or the transient reservoir of photosynthates (Sharkey, 1985a; Stitt et al., 2010; McClain and Sharkey, 2019). According to the widely accepted C3 photosynthetic model of Farquhar et al. (1980) and von Caemmerer (2000), the maximal A at low [CO2] is thought to be determined by the enzymatic capacity of Rubisco, whereas that at elevated [CO2] is thought to be determined by the capacity for regeneration of the Rubisco substrate, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP). In addition, Sharkey (1985a) proposed that the availability of inorganic phosphate (Pi) for ATP synthesis, which depends on sucrose or starch synthesis capacity, also limits photosynthesis. Pi-limited photosynthesis is reported to occur at extremely elevated [CO2], combination of elevated [CO2] and low [O2], low temperatures, or strong sink limitation under high irradiance (Sharkey, 1985a, 1985b; Sharkey et al., 1986a, 1986b; Sage et al., 1988; Sage and Kubien, 2007; Busch and Sage, 2017; Fabre et al., 2019; McClain and Sharkey, 2019). Global gross primary productivity under present-day and future conditions is estimated to decrease when Pi-limited photosynthesis is included in the simulation (Lombardozzi et al., 2018), suggesting the importance of this photosynthetic limitation.

The mechanisms underlying the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis are proposed as follows. When sucrose or starch synthesis cannot keep up with an increase in A, the amounts of phosphorylated intermediates leading to sucrose or starch synthesis and those of general phosphorylated compounds including the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolites increase, leading to the depletion of Pi and the limitation of ATP synthesis and photosynthesis. As A is limited by the availability of Pi, the sensitivity of A to [CO2] and [O2] owing to the enzymatic properties of Rubisco is lost (Sharkey, 1985a, 1985b; Sharkey et al., 1986a). Such symptoms in A and even reverse sensitivity of A to [CO2] have been observed (Sharkey, 1985a, 1985b; Sharkey et al., 1986a, 1986b; Sage et al., 1988; Sage and Kubien, 2007; Busch and Sage, 2017; Fabre et al., 2019; McClain and Sharkey, 2019). The metabolic changes mentioned above were observed experimentally (Sharkey et al., 1986a, 1986b; Sage et al., 1988). Simultaneously, decreases in the activation state of Rubisco were observed (Sharkey et al. 1986a, 1986b; Sage et al. 1988). As expected from this theory, suppression of cytosolic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase activity in mutants or transgenic plants led to the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis and concomitant metabolic changes (Sharkey et al., 1988; Zrenner et al., 1996; Strand et al., 2000). In addition, in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) knockout mutants of the triose phosphate/phosphate translocator lost the CO2 sensitivity of A at elevated [CO2], suggesting the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis (Schneider et al., 2002; Walters et al., 2004). It is noted that Pi-limited photosynthesis is less related to the level of P nutrition. As the buffering action of vacuoles for Pi is strong, changes in [Pi] in plastids are relatively small when plants are grown under low or high P nutrition levels (McClain and Sharkey, 2019). Although the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis is closely related to the metabolic changes in the Calvin–Benson cycle, the symptoms of Pi-limited photosynthesis have rarely been reported when the capacities of the Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes were genetically modified. For instance, suppression of the Calvin–Benson enzymes after Rubisco, such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), aldolase, transketolase, and sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase), led to RuBP-regeneration limited photosynthesis (Price et al., 1995; Haake et al., 1998; Ruuska et al., 2000; Harrison et al., 2001; Henkes et al., 2001).

There are some Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes whose control over A have not been examined. One example is chloroplast triose phosphate isomerase (cpTPI), which catalyzes the interconversion of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), whereas the cytosolic isoform (cytTPI) is responsible for the same reaction in glycolysis (Bukowiecki and Anderson, 1974; Kurzok and Feierabend, 1984; Pichersky and Gottlieb, 1984). Generally, TPI is thought to be a fast and efficient enzyme (Knowles and Albery, 1977; Blacklow et al., 1988). The capacity of cpTPI was estimated to be very high and thought to be in large excess for photosynthesis (Fridlyand, 1992; Harris and Königer, 1997; Fridlyand et al., 1999). In contrast, there are some indications that in vivo cpTPI activity affects the metabolism related to the Calvin–Benson cycle. cpTPI was found to be inhibited by 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PG), the product of Rubisco oxygenation reaction, in Arabidopsis mutants and transformants in which 2-PG over-accumulated owing to dysfunctions in the photorespiratory metabolism (Flügel et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). Concomitantly, the pool sizes of most of the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolites decreased (Flügel et al., 2017). The inhibitory effects of 2-PG were suggested to lead to the disequilibrium of cpTPI reaction in wild-type (WT) Arabidopsis plants, as the GAP:DHAP ratio measured was higher than expected from the equilibrium state (Li et al., 2019). The higher concentration of GAP is thought to be favorable for photosynthesis, as much more energy is provided to drive the aldolase reaction and help synthesis of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) (Sharkey, 2019). The contribution of cpTPI to primary metabolism and plant development has only been examined in a cptpi-knockdown Arabidopsis mutant (Chen and Thelen, 2010). This mutant showed an amount of cpTPI decreased by 75% and over-accumulation of some by-products of triacylglycerol catabolism, including DHAP and methylglyoxyal, during the early stage of plant development. These phenomena led to the inhibition of the transition from heterotrophic growth to photoautotrophic growth, and hence, severely stunted growth. Probably, because of such growth characteristics, the photosynthetic characteristics of this mutant are unknown.

In this study, we aim to investigate whether the capacity of cpTPI affects photosynthetic capacity. For this purpose, transgenic plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI were generated in rice (Oryza sativa). As triacylglycerol is not the major form of carbon storage in rice seeds, the negative effects of its catabolism are expected to be avoided. cpTPI-antisense rice plants grew photoautotrophically without severe abnormalities but showed the typical symptoms of Pi-limited photosynthesis. To obtain further evidence for the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis, metabolic changes related to the Calvin–Benson cycle were examined. In addition, the control of cpTPI over A was evaluated from relationships between A measured at different [CO2] and the amounts of cpTPI. These parameters were expressed per unit amount of total leaf-N, as there tended to be some variations in the amounts of total leaf-N depending on the genotypes. It is shown that insufficient capacity of cpTPI evokes Pi-limited photosynthesis and reverse CO2 sensitivity of A at elevated [CO2]. These results suggest that the functioning of cpTPI is crucial for photosynthesis at elevated [CO2].

Results

Generation of cpTPI-antisense transgenic rice plants

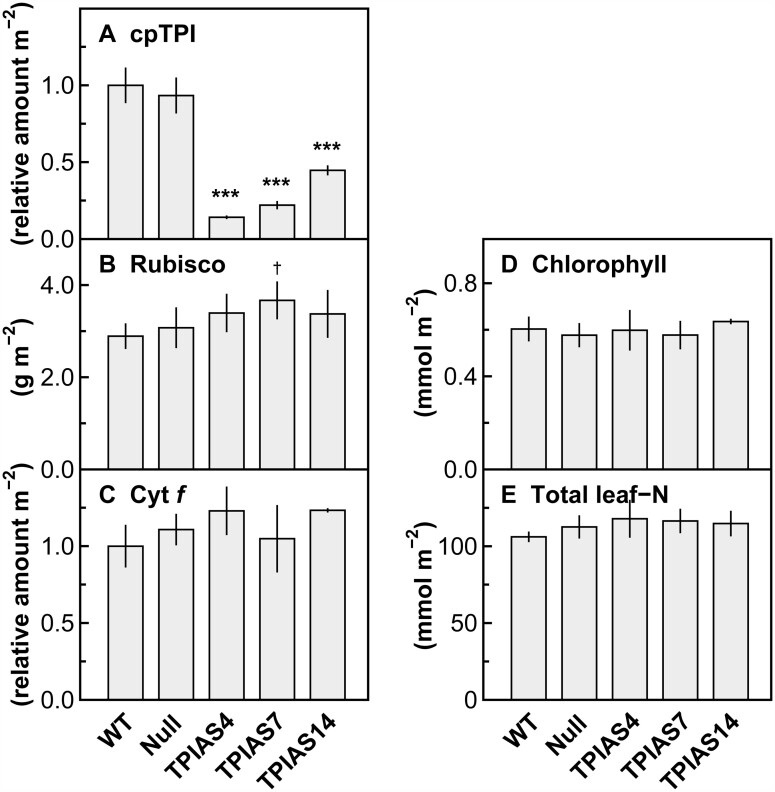

In rice, one gene (Os09g0535000) is annotated as cpTPI (Zhang et al., 2010; Izawa et al., 2011; Hamamoto et al., 2012). To suppress gene expression of cpTPI in leaves, antisense RNA was expressed under the control of the promoter of rice Rubisco small subunit 2 (RBCS2) (Kyozuka et al., 1993). Its promoter activity is expected to be weak in tissues other than leaves, according to the transcript levels of RBCS2 in various rice tissues (Suzuki et al., 2009a; Sato et al., 2013). Three transgenic plant lines (TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14) were selected for analysis. Plants were grown under a strong light intensity (photosynthetic photon flux density [PPFD] of 1,000-μmol quanta m−2 s−1 at a maximum) and a normal [CO2] of 40 Pa throughout the experiments. The amounts of cpTPI, Rubisco, and cytochrome f (Cyt f) subunit of the cytochrome b6/f complex, chlorophyll, and total leaf-N were determined in mature leaves of T2 progenies of these transgenic plants (Figure 1). WT plants and null segregants obtained from transgenic plants were used as control plants. The cpTPI protein was detected by immunoblotting using a peptide antibody designed to avoid cross-reaction to cytTPI. Single bands were detected at ∼26 kDa (Supplemental Figure S1), which is similar to the value for the cpTPI monomer in spinach (Spinacia oleracea) and rye (Secale cereale) (27 kDa; Pichersky and Gottlieb, 1984; Kurzok and Feierabend, 1984). When the transit peptide predicted using ChloroP (Emanuelsson et al., 1999) was excluded from the full-length amino acid sequence for rice cpTPI, the molecular weight was calculated to be 27.4 kDa. The amount of cpTPI protein decreased to 14%, 22%, and 45% of those in WT plants in lines TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14, respectively (Figure 1A). The specificity of the antibody for cpTPI was tested by activity staining of TPI after crude extracts were separated by native-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by immunoblotting (Supplemental Figure S2A). Two bands were detected using activity staining. Only a band with high mobility was detected by immunoblotting. These results are in accordance with the previous observations by Dorion et al. (2005) and Chen and Thelen (2010) that the bands of TPI activity with high and low mobility correspond to cpTPI and cytTPI, respectively. Thus, the peptide antibody for cpTPI was unlikely to cross-react with cytTPI. When all genotypes were subjected to activity staining, trends in differences in the band intensities of cpTPI resembled those in the amounts of cpTPI (Supplemental Figure S2B; Figure 1A), whereas the band intensities of cytTPI did not differ markedly among the genotypes (Supplemental Figure S2B). These results also suggest that the amounts of cpTPI specifically decreased.

Figure 1.

Photosynthetic components in transgenic plants. Amounts of (A) cpTPI; (B) Rubisco; (C) Cyt f; (D) chlorophyll; and (E) total leaf-N in the uppermost and fully expanded leaves in WT plants, null plants, and transgenic plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI (TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14) in rice. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 4). † and *** denotes a significant difference in comparison with the values in WT plants by the Dunnett’s test at P < 0.1 and P < 0.001, respectively.

In these lines, the amounts of Rubisco, Cyt f, and total leaf-N tended to be slightly greater than in WT plants in most cases (Figure 1, B, C, and E). In contrast, the amounts of chlorophyll in these lines were almost identical to that in WT plants (Figure 1D). The characteristics of null plants were similar to those of WT plants (Figure 1, A–E). These results indicate that transgenic rice plants with decreased amounts of cpTPI were successfully generated. The results of immunoblotting for the determination of Cyt f are presented in Supplemental Figure S3.

In contrast to the cptpi-knockdown Arabidopsis mutant (Chen and Thelen, 2010), severe abnormalities in transgenic rice plant growth were not observed. The representative appearance of cpTPI-antisense plants on the 61st day after sowing is presented in Supplemental Figure S4A. Biomass production in lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 was ∼70% of that in WT plants, whereas those in line TPIAS14 and null plants did not differ considerably from that in WT plants (Supplemental Figure S4B). The main reason for growth abnormality in the Arabidopsis mutant was the metabolic disorder related to triacylglycerol catabolism during the early stage of plant development (Chen and Thelen, 2010). Such effects were likely to be avoided in rice, in which the major form of seed carbon storage is starch. The use of the RBCS2 promoter for antisense suppression could be another reason as its activity is expected to be high only in leaf blades.

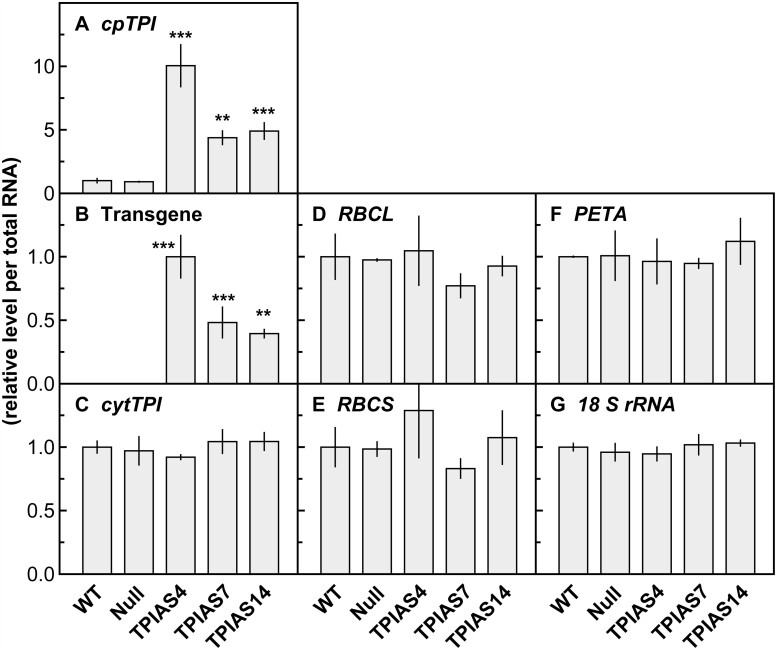

Transcript levels of the genes for cpTPI, cytTPI, Rubisco, and Cyt f were determined along with transcript levels of the transgene, that is, the antisense construct for cpTPI (Figure 2). Surprisingly, transcript levels of cpTPI were substantially higher in cpTPI-antisense plants than in other genotypes (Figure 2A). This result was confirmed when almost the entire region of the full-length cDNA for cpTPI was amplified by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Supplemental Figure S5). Similar trends were observed when the expression levels of transgene were examined by amplifying the conjunction region of the RBCS2 promoter and cpTPI antisense cDNA (Figure 2B). In both cases, these transcript levels were the highest in line TPIAS4, in which the amount of cpTPI protein was most severely suppressed (Figure 1A). Although gene expression of cpTPI might have been suppressed by co-suppression, the reason for the substantial increase in transcript levels of cpTPI is unknown. In rice, two genes (Os01g0147900 and Os01g0841600) are annotated as cytTPI (Izawa et al., 2011; Hamamoto et al., 2012). As transcript levels in various tissues, including leaves, were much higher in Os01g0147900 than in Os01g0841600 (Izawa et al., 2011; Sato et al., 2013), Os01g0147900 was selected as the dominant cytTPI gene. Transcript levels of cytTPI were similar among the genotypes (Figure 2C). There were also no significant differences in the transcript levels of the genes for Rubisco large subunit (RBCL), RBCS, and Cyt f (PETA) (Figure 2, D–F). These results indicate that antisense suppression of cpTPI did not affect the gene expression of cytTPI, Rubisco, and Cyt f. The characteristics of null plants were similar to those of WT plants (Figure 2, A–F). Levels of internal standard 18 S rRNA were almost identical among the genotypes (Figure 2G), indicating the validity of the analyses.

Figure 2.

Transcript levels of photosynthesis-related genes and transgene in transgenic plants. Transcript levels of (A) cpTPI; (B) transgene for antisense suppression of cpTPI; (C) cytTPI; (D) RBCL; (E) RBCS; and (F) PETA in young and expanding leaves in WT plants, null plants, and transgenic plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI (TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14) in rice. (G) Levels of 18 S rRNA were also presented as controls. Data are presented as the means ± sd (n = 3). ** and *** denote a significant difference in comparison with the values in WT plants by the Dunnett’s test at P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

Photosynthetic characteristics in cpTPI-antisense plants

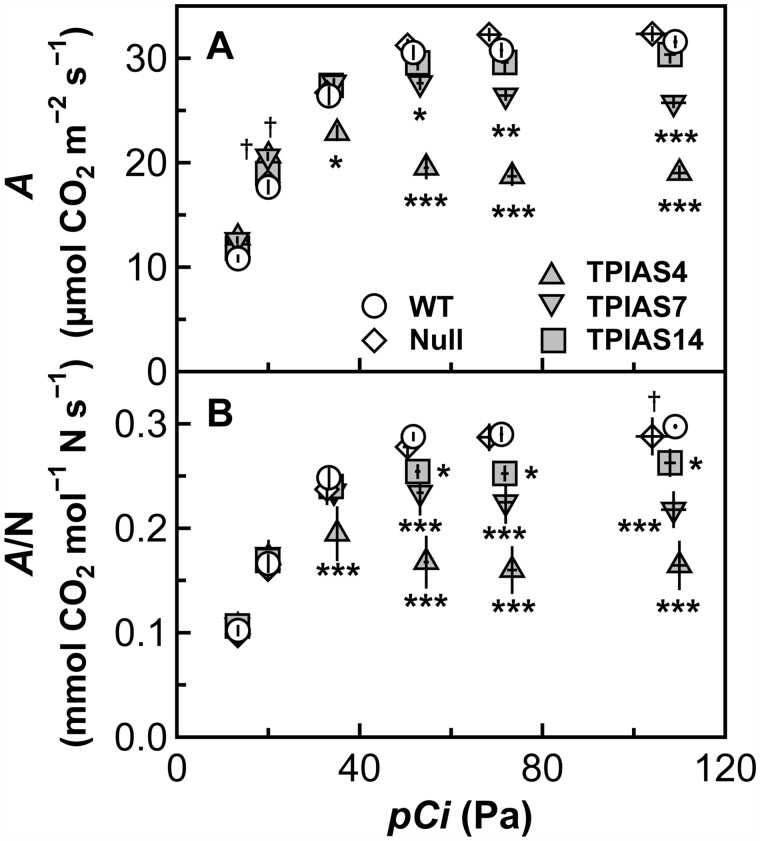

Photosynthetic characteristics in cpTPI-antisense plants were examined by measuring A under a PPFD of 1,500-μmol quanta m−2 s−1 and various [CO2] (Figure 3). On a leaf area basis, there were no large differences in A among the genotypes at intercellular CO2 partial pressures (pCi) of 13.5 and 20 Pa (Figure 3A). In line TPIAS4, A was 86% of that in WT plants at an ambient CO2 partial pressure (pCa) of 40 Pa and tended to decrease as [CO2] increased. At pCa ≥ 60 Pa, A in line TPIAS4 was 61%–64% of that in WT plants. In line TPIAS7, A was similar to that in WT plants at pCa = 40 Pa and tended to slightly decrease as [CO2] increased. At pCa ≥ 60 Pa, A in line TPIAS7 was 80%–89% of that in WT plants. There were no large differences in A between WT plants and line TPIAS14 or null plants at pCa ≥ 40 Pa.

Figure 3.

Photosynthetic characteristics in transgenic plants. The rate of CO2 assimilation (A) in the uppermost and fully expanded leaves were measured with an LI-6400XT at a PPFD of 1,500 µmol quanta m−2 s−1, a leaf temperature of 25°C, and different CO2 partial pressures (intercellular CO2 partial pressure of 13.5 and 20 Pa and ambient CO2 partial pressure of 40, 60, 80, and 120 Pa) in WT plants, null plants, and transgenic plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI (TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14) in rice. A was presented per unit of leaf area (A) and per unit amount of total leaf-N (A/N) (B). White circles, white diamonds, gray upward-pointing triangles, gray downward-pointing triangles, and gray squares indicate WT plants, null plants, TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14, respectively. Data are presented as the means ± sd (n = 4). †, *, **, and *** denote a significant difference in comparison with the values of A or A/N in WT plants by the Dunnett’s test at P < 0.1, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

A is usually affected by the amount of total leaf-N. The amount of total leaf-N tended to be slightly higher in cpTPI-antisense plants (Figure 1E), possibly reflecting the decreased biomass production, at least in the case of TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 (Supplemental Figure S4B). Therefore, A per unit amount of total leaf-N (A/N) was calculated to cancel the effects of total leaf-N (Figure 3B). Although overall trends were unchanged, differences between line TPIAS14 and WT plants were significant when evaluated by A/N, as A/N in line TPIAS14 decreased to 87%–88% of that in WT plants at pCa ≥ 60 Pa. These results clearly indicate that A/N at elevated [CO2] decreased as the amount of cpTPI decreased.

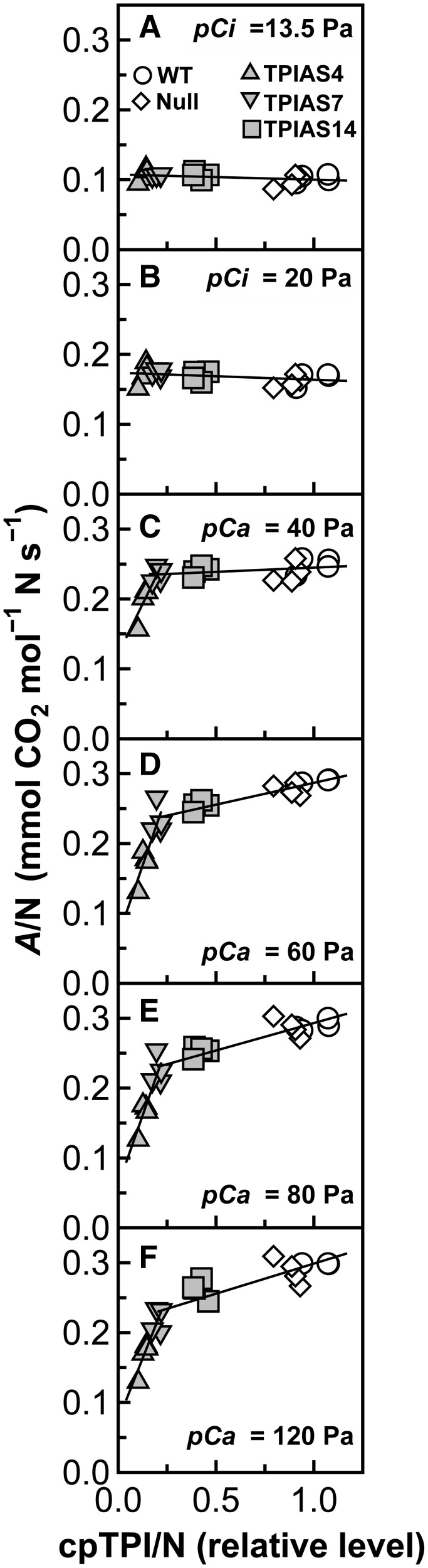

Relationships between A/N and the amount of cpTPI per unit amount of total leaf-N (cpTPI/N), instead of these parameters on a leaf area basis, were examined (Figure 4). Formulae of the regression lines and their Pearson correlation coefficients and P-values are presented in Supplemental Table S1. Significant correlations (P < 0.05) were not observed at pCi of 13.5 and 20 Pa (Figure 4, A and B). A similar trend was observed at a pCa of 40 Pa among the genotypes except TPIAS4 (Figure 4C), in which further decreases in cpTPI/N led to sharp decreases in A. In contrast, at pCa ≥ 60 Pa, strong, positive, and linear correlations were observed between these parameters among the genotypes except TPIAS4 with R > 0.85, and P < 0.001 (Figure 4, D–F; Supplemental Table S1). Decreases in cpTPI/N by 80% led to decreases in A/N at pCa = 60, 80, and 120 Pa by 19%, 22%, and 27%, respectively. In addition, the slopes of the regression lines tended to increase as [CO2] increased (Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 4.

Relationships between A per unit amount of total leaf-N (A/N) and the amount of cpTPI per unit amount of total leaf-N (cpTPI/N). Data are taken from Figures 1, A and E, and 3B. Relationships observed at (A) intercellular CO2 partial pressure (pCi) of 13.5 Pa; (B) pCi of 20 Pa; (C) ambient CO2 partial pressure (pCa) of 40 Pa; (D) pCa of 60 Pa; (E) pCa of 80 Pa; and (F) pCa of 120 Pa. Symbols are the same as in Figure 3. In (A) and (B), solid lines represent the regression line obtained using all genotypes. In each part of (C) to (F), one solid line represents the regression line obtained using WT plants, null plants, TPIAS14, and TPIAS7, whereas another solid line represents the regression line obtained using TPIAS7 and TPIAS4. Formulae and Pearson correlation coefficients for these regression lines are presented in Supplemental Table S1.

Changes in the Calvin–Benson cycle and its related metabolism in cpTPI-antisense plants

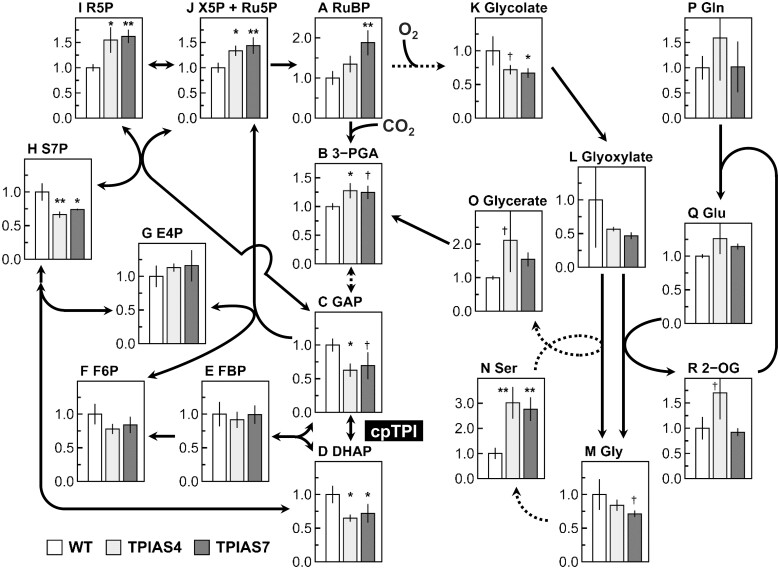

As A under elevated [CO2] decreased in cpTPI-antisense plants, the pool sizes of the Calvin–Benson cycle and photorespiration metabolites were determined at pCa = 80 Pa in lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 and WT plants (Figure 5). After A was equilibrated, leaves were immediately frozen using the rapid-kill system (Badger et al., 1984; Suzuki et al., 2012), followed by capillary electrophoresis-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOFMS) analysis. The pool sizes were presented as relative values to those of WT plants on a leaf area basis. In lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7, the pool sizes of both GAP and DHAP decreased to ∼60%–70% of those in WT plants (Figure 5, C and D). Decreases of a similar magnitude were observed for sedoheptulose 7-phosphate (S7P) (Figure 5H). Similar trends were observed for fructose 6-phosphate (F6P) (Figure 5F). Simultaneously, the pool sizes of the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolites from pentose phosphate to 3-PGA increased to 125%–188% of those in WT plants (Figure 5, A, B, I, and J). As for the metabolites involved in photorespiration, the pool sizes of glycolate, glyoxylate, and Gly tended to decrease (Figure 5, K–M), whereas those of Ser and glycerate tended to increase (Figure 5, N and O). The pool sizes of the metabolites involved in sucrose or starch synthesis tended to generally decrease in lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 (Table 1). The pool sizes of ATP also decreased by ∼15%, whereas significant differences were not observed for ADP and AMP (Table 2). In contrast, drastic increases were observed in the pool size of NADPH in these lines, especially in line TPIAS4 (Table 2). In addition, the pool sizes of many other metabolites were affected by the suppression of cpTPI, as presented in Supplemental Table S2.

Figure 5.

Pool sizes of the metabolites involved in the Calvin–Benson cycle and photorespiration in transgenic plants. WT rice plants and transgenic rice plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI (TPIAS4 and TPIAS7) were used as samples. The rate of CO2 assimilation (A) in the uppermost and fully expanded leaves were monitored using a rapid-kill chamber (Badger et al., 1984; Suzuki et al., 2012) connected to an LI-6400XT at a photosynthetic photon flux density of 1,500-µmol quanta m−2 s−1, a leaf temperature of 25°C, and ambient CO2 partial pressure of 80 Pa. After A was in a steady-state, leaves were immediately frozen with liquid N2, followed by CE-TOFMS analysis. Pool sizes of (A) RuBP; (B) 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA); (C) GAP; (D) DHAP; (E) FBP; (F) F6P; (G) erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P); (H) S7P; (I) ribose 5-phosphate (R5P); (J) sum of xylulose 5-phosphate and ribulose 5-phosphate (X5P + Ru5P); (K) glycolate; (L) glyoxylate; (M) Gly; (N) Ser; (O) glycerate; (P) Gln; (Q) Glu; and (R) 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG). White bars, light gray bars, and dark gray bars indicate WT plants and lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7, respectively. Data are presented as values relative to those in WT plants on leaf area basis (means ± sd, n = 3). †, *, and ** denote a significant difference in comparison with the values in WT plants by the Dunnett’s test at P < 0.1, P < 0.05, and P < 0.01, respectively.

Table 1.

Relative amounts of the metabolites related to starch or sucrose synthesis in transgenic plants

| Metabolite | (Relative amount m−2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | TPIAS4 | TPIAS7 | |

| G6P | 1.00 ± 0.17 | 0.67 ± 0.06* | 0.67 ± 0.12* |

| G1P | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 0.63 ± 0.11* | 0.82 ± 0.11 |

| ADPGlc + GDPFrc | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.18 |

| UDPGlc + UDPGal | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.18 |

| Suc6P | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 0.68 ± 0.04** | 0.77 ± 0.10* |

These metabolites were determined simultaneously with those presented in Figure 5 in WT plants and transgenic plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI (TPIAS4 and TPIAS7) in rice. G6P, G1P, ADPGlc + GDPFrc, UDPGlc + UDPGal, and Suc6P represent G6P, glucose 1-phosphate, the sum of ADP-glucose and GDP-fructose, the sum of UDPG and UDP-galactose, and sucrose 6-phosphate, respectively. Data are presented as the relative values to those in WT plants on a leaf area basis (means ± sd, n = 3). * and ** denote a significant difference in comparison with the values in WT plants by the Dunnett’s test at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Table 2.

Relative amounts of adenine nucleotides, NADPH, and NADP+ in transgenic plants

| Metabolite | (Relative amount m−2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | TPIAS4 | TPIAS7 | |

| ATP | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.06* | 0.85 ± 0.06† |

| ADP | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| AMP | 1.00 ± 0.16 | 1.08 ± 0.20 | 0.96 ± 0.42 |

| NADPH | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 4.72 ± 0.41* | 2.60 ± 1.29† |

| NADP+ | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.19* | 0.98 ± 0.08 |

These metabolites were determined simultaneously with those presented in Figure 5 in WT plants and transgenic plants with antisense suppression of cpTPI (TPIAS4 and TPIAS7) in rice. Data are presented as the relative values to those in WT plants on a leaf area basis (means ± sd, n = 3). † and * denote a significant difference in comparison with the values in WT plants by the Dunnett’s test at P < 0.1, and P < 0.05, respectively.

Discussion

Suppression of cpTPI evokes the typical symptoms of Pi-limited photosynthesis

Not only did the CO2 sensitivity of A decrease at pCa ≥ 60 Pa in line TPIAS14, but the reverse CO2 sensitivity of A was also observed in lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 (Figure 3, A and B). These symptoms are typical for Pi-limited photosynthesis (Sharkey, 1985a, 1985b; Sharkey et al. 1986a, 1986b; Sage et al. 1988; Sage and Kubien, 2007; Busch and Sage, 2017; Fabre et al., 2019; McClain and Sharkey, 2019). Pi-limited photosynthesis has been reported to induce metabolic changes, including increases in the pool size of F6P, glucose 6-phosphate (G6P), UDP-glucose (UDPG), RuBP, 3-PGA, and triose-phosphates, and decreases in the pool size of ATP and the ATP/ADP ratio (Sharkey et al. 1986a, 1988; Sage et al. 1988; Zrenner et al., 1996; Strand et al., 2000). Such changes resembled those observed in isolated chloroplasts photosynthesizing under low [Pi], in which a decrease in the pool size of triose-phosphates was also observed (Heldt et al., 1978). The metabolic changes in lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 were similar to these changes, as the pool sizes of the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolites from pentose phosphates to 3-PGA tended to increase, whereas the pool size of ATP decreased (Figure 5, A, B, I, and J; Table 2). These results strongly suggest that suppression of cpTPI evokes Pi-limited photosynthesis even at moderately elevated [CO2] and normal [O2], and that sufficient capacity of cpTPI is necessary to prevent the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis.

In previous studies on the suppression of Calvin–Benson enzymes after Rubisco, such as GAPDH, aldolase, transketolase, and SBPase, RuBP-regeneration limited photosynthesis was thought to occur (Price et al., 1995; Haake et al., 1998; Ruuska et al., 2000; Harrison et al., 2001; Henkes et al., 2001). In contrast to this study, the pool sizes of RuBP and 3-PGA were observed to decrease in most of these studies and the suppression studies of phosphoribulokinase (Paul et al., 1995, 2000; Price et al., 1995; Haake et al., 1998; Ruuska et al., 2000; Henkes et al., 2001). This difference in the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolism might be one of the causes for the difference in the symptoms in photosynthesis. Interestingly, the CO2 sensitivity of A tended to decrease in transgenic rice plants with overproduction of Rubisco (Makino and Sage, 2007), in which over-accumulation of phosphorylated compounds including 3-PGA and S7P was observed (Suzuki et al., 2012).

Possible mechanism for the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis via suppression of cpTPI

Typical Pi-limited photosynthesis is thought to occur owing to a limitation in the use of triose phosphates for sucrose or starch synthesis and the regeneration of Pi via these processes (Sharkey, 1985a, 1985b; Sharkey et al., 1986a). This study suggests another mechanism for Pi-limited photosynthesis caused by a limitation of the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolism at the step of cpTPI. The mechanisms for the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis have been investigated from changes in the fluxes and pool sizes of the metabolites related to Calvin–Benson cycle and sucrose or starch synthesis (Sharkey et al., 1986a; Sage et al., 1988). How Pi-limited photosynthesis was evoked via suppression of cpTPI is discussed in relation to changes in the pool sizes of the metabolites when A reached the steady state (Figure 5).

Suppression of cpTPI would initially suppress the conversion of GAP to DHAP, leading to reduced synthesis of sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate (SBP) and FBP owing to reduced availability of DHAP and a limitation of the Calvin–Benson cycle metabolism. These events were likely to lead to the decrease in the pool size of S7P at the steady-state conditions (Figure 5H). The pool size of F6P also tended to slightly decrease (Figure 5F), although its interpretation is complicated as F6P is present in both in the chloroplast and cytosol (Gerhartd et al., 1987). Similar events were thought to occur in isolated chloroplasts photosynthesizing under low [Pi], as the pool size of SBP decreased (Heldt et al., 1978). Decreases in the pool sizes of FBP, F6P, SBP, and S7P were also observed in Arabidopsis mutants and transformants in which cpTPI was inhibited by over-accumulation of 2-PG (Flügel et al., 2017). In turn, C supplied for sucrose or starch synthesis was thought to be insufficient, leading to the decreases in the pool size of the intermediates for sucrose or starch synthesis at the steady-state conditions (Table 1). This event would prevent the regeneration of Pi via sucrose or starch synthesis. Transient increases in the pool size of triose phosphates might simultaneously occur, leading to sequestration of Pi. Then, ATP synthesis was thought to be limited by Pi availability, leading to the decrease in its pool size (Table 2) and the CO2-insensitivity of A (Figure 3). As observed in the typical Pi-limited photosynthesis (Sharkey et al. 1986a, 1986b; Sage et al. 1988), the activation state of Rubisco probably decreases, leading to the increases in the pool size of pentose phosphates to RuBP (Figure 5, A, I, and J). The occurrence of Rubisco deactivation is predicted from the decreasing trends in the pool sizes of the photorespiratory metabolites, such as glycolate, glyoxylate, and Gly (Figure 5, K–M). These events have previously been observed when Rubisco capacity decreased in RBCS-antisense rice plants (Suzuki et al., 2012). In contrast, the amounts of Rubisco in lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7 were not lower than that in WT plants (Figure 1B), suggesting the occurrence of Rubisco deactivation. The decreases in ATP availability were likely to decrease the production of triose phosphates and their pool sizes at the steady-state conditions (Figure 5, C and D). These events could also lead to the drastic increase in the pool size of NADPH (Table 2) owing to a decrease in its consumption by the GAPDH reaction. In Arabidopsis mutants and transformants with the cpTPI inhibition by over-accumulated 2-PG, the increases in the pool sizes of pentose phosphates to 3-PGA were not observed, probably because 2-PG also inhibited SBPase (Flügel et al., 2017).

Capacity of cpTPI moderately affects photosynthetic capacity at elevated [CO2]

A/N and cpTPI/N at pCa ≥ 60 Pa were strongly and linearly correlated among the genotypes except TPIAS4 (Figure 4, D–F). A/N moderately decreased as cpTPI/N decreased within this range of cpTPI/N. The slope of the regression lines tended to increase slightly as the [CO2] increased (Supplemental Table S1). In contrast, the decrease in the amount of cpTPI did not affect A at low [CO2] (Figure 3A), where Rubisco is thought to limit A (Farquhar et al., 1980; von Caemmerer 2000). These results suggest that the capacity of cpTPI moderately affect the photosynthetic capacity at elevated [CO2]. The control of cpTPI over A might be weaker than that of other Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes, such as aldolase, transketolase, and SBPase, as the effects on A were reported to be stronger when the activities of these enzymes were suppressed (Haake et al., 1998; Harrison et al., 2001; Henkes et al., 2001). To further investigate the control of cpTPI over A and to improve photosynthetic capacity, overproduction of cpTPI also need to be conducted. It has been reported that overproduction of SBPase, aldolase, and GAPDH led to an improvement in the photosynthetic capacity at elevated [CO2] to some extent (Lefebvre et al., 2005; Driever et al., 2017; Simkin et al., 2017; Suzuki et al., 2021a), whereas no effects have been reported for transketolase (Khozaei et al., 2015; Suzuki et al., 2017) and SBPase in rice (Suzuki et al., 2019). If cpTPI has a control over A, co-overproduction of cpTPI and other Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes is also of interest for further improving photosynthetic capacity. So far, the magnitude of improvement in photosynthetic capacity seems to be rather limited, if any, when some Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes are co-overproduced (Simkin et al., 2015, 2017; Suzuki et al., 2017, 2019, 2021b), whereas co-overproduction of Rubisco and Rubisco activase was effective for improving photosynthetic capacity at low to normal [CO2] and moderately high temperatures (Suganami et al., 2021; see also Makino, 2021).

Conclusions

In this study, suppression of cpTPI is strongly suggested to evoke the limitation of photosynthesis by Pi availability for ATP synthesis at elevated [CO2], as judged from the responses of A to [CO2] and the changes in the metabolism related to Calvin–Benson cycle. Enough capacity of cpTPI is suggested to be necessary to avoid Pi-limited photosynthesis at elevated [CO2]. This is the second mechanism for the occurrence of Pi-limited photosynthesis, as it has been thought to be caused by a limitation in sucrose or starch synthesis. In addition, the photosynthetic capacity at elevated [CO2] was moderately affected by the capacity of cpTPI. It is of interest and to be studied how overproduction of cpTPI and its co-overproduction with other Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes affect photosynthesis.

Materials and methods

Generation of transgenic plants

The gene expression of cpTPI (Os09g0535000) was suppressed in rice (O. sativa) by expressing the full-length cDNA of cpTPI in an antisense orientation under the control of the rice RBCS2 promoter (Kyozuka et al., 1993). A binary vector pBIRS (Suzuki et al., 2007) was digested with Hind III and Sac I. The rice RBCS2 promoter was amplified by PCR from pBIRS as a template using KOD-Plus-Neo (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). DNA fragments containing the full-length cDNA of cpTPI were amplified by RT-PCR using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan) and KOD-Plus-Neo (TOYOBO). The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S3. These DNA fragments were cloned into the digested pBIRS using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to generate vectors for antisense suppression of cpTPI. The vector was introduced into rice (“Notohikari”) using the Agrobacterium transformation method (Toki et al., 2006). T0 progenies of transgenic plants were grown hydroponically in an isolated and temperature-controlled greenhouse, as described by Suzuki et al. (2007). Transgenic lines with a decrease in the amount of cpTPI protein were selected by immunoblotting as described by Yamaoka et al. (2016), with some modifications as described later. Transgenic lines with a substantial decrease in the amount of cpTPI protein were selected.

Screened transgenic lines were allowed to self-fertilize so that T1 seeds could be collected. T1 progenies were grown hydroponically in an isolated and temperature-controlled greenhouse, as described by Suzuki et al. (2007). Homozygotes were selected before transplantation using the comparative cycle threshold method (Prior et al., 2006) as described by Ogawa et al. (2012). Cytoplasmic glutathione reductase (Os02t0813500-01) and the region from the 3′-end of the RBCS2 promoter to the 5′-end of the cpTPI fused to the RBCS2 promoter in an antisense orientation were used to detect the endogenous reference gene and transgenes, respectively. The primer pairs and probes used are listed in Supplemental Table S4. The selected T1 progenies were allowed to self-fertilize to collect the T2 seeds. Among the T2 progenies, three lines with a substantial decrease in the amount of cpTPI protein (TPIAS4, TPIAS7, and TPIAS14) and null segregants were used in this study.

Plant culture and sampling

The cpTPI-antisense plants, null plants, and WT rice plants (“Notohikari”) were hydroponically grown in an environmentally controlled growth chamber (NC-411HC, NKsystem, Osaka, Japan). LED light unit and fluorescent tube lights used were described by Suzuki et al. (2021a). Seedlings were grown in tap water for 19 days after sowing. The maximum light intensity during the daytime was a PPFD of 500-µmol quanta m−2 s−1, with a photoperiod of 14 h. The maximum day and night temperatures were 25°C and 20°C, respectively. [CO2] and relative humidity were adjusted to 40 Pa and 60%, respectively. Thereafter, one seedling was transplanted to a 1.1 L plastic pot containing nutrient solution as previously described by Makino et al. (1988). The maximum light intensity during the daytime was a PPFD of 1,000-µmol quanta m−2 s−1, with a photoperiod of 14 h. The maximum day and night temperatures were 27°C and 22°C, respectively. [CO2] and relative humidity were adjusted to 40 Pa and 60%, respectively. The strength of the nutrient solution was changed according to plant growth as follows: 1/3 strength for 2 weeks, 1/2 strength for 1 week, 2/3 strength for 1 week, and full strength thereafter. On the 42nd day after transplanting, which corresponds to the 61st day after sowing, leaf blades, leaf sheaths, and roots were harvested separately, dried at 70°C for more than a week, and used for the measurement of plant biomass. From the 42nd day after transplanting, the uppermost, fully expanded leaves were collected after measuring A and stored at −80°C until biochemical assays. Leaf area was measured using a scanner and ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012). Leaves that had emerged from their sheaths by 50% were also collected for RNA analysis, as described by Suzuki et al. (2007).

Measurements of gas exchange

A was measured using a portable gas exchange system (LI-6400XT, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). Plants were placed in an environmentally controlled growth chamber (NC-411HC, NKsystem, Osaka, Japan) operated with a PPFD of 500-µmol quanta m−2 s−1, a [CO2] of 40 Pa, and an air temperature of 25°C for at least 30 min. After the plants were taken out from the growth chamber, measurements of A were immediately initiated at a PPFD of 1,500-µmol quanta m−2 s−1, a pCa of ∼26 Pa, a leaf temperature of 25°C, and a leaf-to-air vapor pressure difference of 1.0–1.2 kPa. After A increased and reached the steady state at pCi = 20 Pa, [CO2] was changed to obtain pCi = 13.5 Pa, and pCa = 40, 60, 80, and 120 Pa. Gas exchange parameters were calculated according to the equations proposed by von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981).

Biochemical assays

Frozen leaves were homogenized in a chilled mortar with pestle in 50 mM Na-phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 2-mM iodoacetic acid, 0.8% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5% (v/v) glycerol (Suzuki et al., 2007). An aliquot of the homogenate was used for chlorophyll determination using Arnon’s (1949,) method. Another aliquot was subjected to Kjeldahl digestion, followed by determination of total N using Nessler’s reagent (Makino et al., 1984). A part of the remaining homogenate was centrifuged at 17,900g for 5 min at 4°C. An equal volume of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (150 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.5] containing 2% [w/v] SDS, 20% [v/v] glycerol, and 5% [v/v] 2-mercaptoethanol) was added to the resulting supernatant. The mixture was boiled for 2 min and used for determination of cpTPI protein by immunoblotting. A sample for Rubisco determination was prepared in a similar manner, except that Triton X-100 was added to a part of the remaining homogenate at a final concentration of 0.1% (v/v). Another part of the remaining homogenate was directly treated with SDS sample buffer and centrifuged at 17,900 g for 5 min at room temperature. The resulting supernatant was used for determination of the amount of the Cyt f subunit of the cytochrome b6/f complex by immunoblotting. These SDS-treated samples were kept at –30°C until use.

The amounts of cpTPI and Cyt f protein were determined by immunoblotting using TGX FastCast acrylamide kit with 12% (w/v) acrylamide (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), a semi-dry blotting apparatus (Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System; Bio-Rad), a PVDF membrane (Trans-Blot Turbo RTA Transfer Kit, Mini, PVDF; Bio-Rad), the chemiluminescence detection kits described below, and an image analyzer (ImageQuant LAS 4000, Citiva, Tokyo, Japan) as described by Yamaoka et al. (2016) and Wada et al. (2019), respectively, with slight modifications. In the case of cpTPI determination, an aliquot of an SDS-treated sample corresponding to 70 µg of leaf fresh weight was loaded onto a gel, except that the amount of sample loaded corresponded to 140 µg of leaf fresh weight in the case of lines TPIAS4 and TPIAS7. Different volumes of SDS-treated samples prepared from WT plants were loaded to construct a calibration curve. An antiserum against the fragment of the cpTPI protein [residues 149–162 (HVIGEDDQFIGKKA) of the deduced amino acid sequence of Os09t0535000-02] raised in rabbit (Sigma Aldrich Japan, Ishikari, Japan) was used for immunological detection. Signals were detected using a chemiluminescence detection kit (SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan). In the case of Cyt f determination, an aliquot of SDS-treated sample corresponding to 20 µg of leaf fresh weight was loaded onto a gel. A chemiluminescence detection kit (ECL Start, Citiva) was used. In both cases, quantification of detected signals was performed using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012).

The amount of Rubisco was determined by formamide extraction of Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250-stained bands corresponding to the large and small subunits of Rubisco separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described by Makino et al. (1985) except that calibration curves were prepared from bovine serum albumin (Pierce™ Bovine Serum Albumin Standard Ampules; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RNA analysis

Total RNA was extracted as described by Suzuki et al. (2004), with slight modifications (Suzuki et al., 2009b). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed as described by Ogawa et al. (2012) and Yamaoka et al. (2016) with some modifications as described by Suzuki et al. (2021a). For determination of the transcript level of RBCS, a part of the coding region that is highly homologous among the RBCS genes expressed highly in leaf blades, that is, RBCS2, 3, 4, and 5 (Suzuki et al., 2009a), was amplified to obtain transcript levels of total RBCS, using the primer pair reported previously (Suzuki et al., 2007). Transcript levels of the transgene were also determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using primers that amplify the conjunction region of the RBCS2 promoter and cpTPI antisense cDNA. To determine the transcript levels of cpTPI and the transgene, calibration curves were prepared with sequentially diluted cDNA prepared from total RNA of line TPIAS4. The primer pairs used are listed in Supplemental Table S5.

Metabolome analysis

A was monitored using a rapid-kill chamber (Badger et al., 1984; Suzuki et al., 2012) connected to LI-6400XT (Li-Cor) under the conditions mentioned earlier, except that measurements were initiated at pCa = 80 Pa. Leaves were immediately frozen with liquid N2 after A was in a steady state and stored at −80°C until analysis. Samples for CE-TOFMS analysis were prepared as described by Suzuki et al. (2012). Briefly, frozen leaves were extracted with methanol, chloroform, and water. The resultant water phases were filtrated, dried, and dissolved in ultrapure water. The samples obtained were subjected to CE-TOFMS analysis using the Agilent CE-TOFMS system (Agilent, CA, USA) as described by Soga and Heiger (2000), Soga et al. (2002, 2003), and Ooga et al. (2011).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test using R version 3.5.0 (Ihaka and Gentleman, 1996) and the package “multicomp” (version 1.4-8 (Hothorn et al., 2008).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in RAP-DB/GenBank under the following accession numbers: cpTPI, Os09g0535000; cytTPI, Os01g0147900; RBCS2, Os12g0274700; RBCS3, Os12g0291100; RBCS4, Os12g0292400; RBCS5, Os12g0291400; RBCL, OrsajCp033; PETA, OrsajCp041.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table S1. Formulae and Pearson correlation coefficients (R) for the regression lines presented in Figure 5.

Supplemental Table S2. Changes in the pool sizes of metabolites determined by CE-TOFMS analysis.

Supplemental Table S3. Primer pairs used for the construction of vectors for antisense suppression of cpTPI in rice.

Supplemental Table S4. Primer pairs and probes used for the selection of homozygotes of rice plants transformed with a binary vector for antisense suppression of cpTPI.

Supplemental Table S5. Primer pairs used for semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Supplemental Figure S1. Results of immunoblotting of cpTPI protein.

Supplemental Figure S2. Results of activity staining of TPI and immunoblotting of cpTPI.

Supplemental Figure S3. Results of immunoblotting of the Cyt f subunit of the cytochrome b6/f complex.

Supplemental Figure S4. Growth of transgenic plants on the 61st day after sowing.

Supplemental Figure S5. RT-PCR analysis for cpTPI and RBCS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Uzuki Matsushima (Iwate University) for assistance with photosynthetic measurements. The authors would also like to thank Human Metabolome Technologies (Tsuruoka, Japan) for the fine techniques of CE-TOFMS analysis and Editage for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Nos. JP18H02111 and 21H02084 to Y.S. and JP16H06379 to A.M.) and Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Grant No. JPMJCR15O3 to Y.S. and C.M.).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Y.S. conceived and designed the experiments. E.K. and M.S. generated the transgenic plants. Y.S., K.I., D.-K.Y., Y.T.-T., and E.K. performed the experiments. All authors analyzed and discussed the data. Y.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is Yuji Suzuki (ysuzuki@iwate-u.ac.jp).

References

- Arnon DI (1949) Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenol oxidases in Beta vlulgaris. Plant Physiol 24:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Sharkey TD, von Caemmerer S (1984) The relationship between steady-state gas exchange of bean leaves and the levels of carbon-reduction-cycle intermediates. Planta 160:305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklow SC, Raines RT, Lim WA, Zamore PD, Knowles JR (1988) Triosephosphate isomerase catalysis is diffusion controlled. Biochemistry 27:1158–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowiecki AC, Anderson LE (1974) Multiple forms of aldolase and triose phosphate isomerase in diverse plant species. Plant Sci Lett 3:381–386 [Google Scholar]

- Busch FA, Sage RF (2017) The sensitivity of photosynthesis to O2 and CO2 concentration identifies strong Rubisco control above the thermal optimum. New Phytol 213: 1036–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin M (1962) The path of carbon in photosynthesis. Science 135:879–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Thelen JJ (2010) The plastid isoform of triose phosphate isomerase is required for the postgerminative transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22:77–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorion S, Parveen, Jeukens J, Matton DP, Rivoal J (2005) Cloning and characterization of a cytosolic isoform of triosephosphate isomerase developmentally regulated in potato leaves. Plant Sci 168:183–194 [Google Scholar]

- Driever SM, Simkin AJ, Alotaibi S, Fisk SJ, Madgwick PJ, Sparks CA, Jones HD, Lawson T, Parry MAJ, Raines CA (2017) Increased SBPase activity improves photosynthesis and grain yield in wheat grown in greenhouse conditions. Phil Trans Royal Soc B 372:20160384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, von Heijne G (1999) ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci 8:978–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR (2013) Improving photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 162: 1780–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre D, Yin X, Dingkuhn M, Clément-Vidal A, Roques S, Rouan L, Soutiras A, Luquet D (2019) Is triose phosphate utilization involved in the feedback inhibition of photosynthesis in rice under conditions of sink limitation? J Exp Bot 70:5771–5783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149:78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel F, Timm S, Arrivault S, Florian A, Stitt M, Fernie AR, Bauwe H (2017) The photorespiratory metabolite 2-phosphoglycolate regulates photosynthesis and starch accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 29:2537–2551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridlyand LE (1992) Enzymatic control of 3-phosphoglycerate reduction in chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1102:115–118 [Google Scholar]

- Fridlyand LE, Backhausen JE, Scheibe R (1999) Homeostatic regulation upon changes of enzyme activities in the Calvin cycle as an example for general mechanisms of flux control. What can we expect from transgenic plants? Photosynth Res 61: 227–239 [Google Scholar]

- Gerhartd R, Stitt M, Heldt HW (1987) Subcellular metabolite levels in spinach leaves. Regulation of sucrose synthesis during diurnal alterations in photosynthetic partitioning. Plant Physiol 83:399–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake V, Zrenner R, Sonnewald U, Stitt M (1998) A moderate decrease of plastid aldolase activity inhibits photosynthesis, alters the levels of sugars and starch, and inhibits growth of potato plants. Plant J 14:147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Königer M (1997) The ‘high’ concentrations of enzymes within the chloroplast. Photosynth Res 54:5–23 [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EP, Olcer H, Lloyd JC, Long SP, Raines CA (2001) Small decreases in SBPase cause a linear decline in the apparent RuBP regeneration rate, but do not affect Rubisco carboxylation capacity. J Exp Bot 52:1779–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto K, Aki T, Shigyo M, Sato S, Ishida T, Yano K, Yoneyama T, Yanagisawa S (2012) Proteomic characterization of the greening process in rice seedlings using the MS spectral intensity-based label free method. J Proteome Res 11:331–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt HW, Chon CJ, Lorimer GH (1978) Phosphate requirement for the light activation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in intact spinach chloroplasts. FEBS Lett 92:234–240 [Google Scholar]

- Heldt HW, Piechulla B (2011) Photosynthetic CO2 assimilation by the Calvin cycle. Plant Biochemistry, Academic Press, London, pp 163–191 [Google Scholar]

- Henkes S, Sonnewald U, Badur R, Flachmann R, Stitt M (2001) A small decrease of plastid transketolase activity in antisense tobacco transformants has dramatic effects on photosynthesis and phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell 13:535–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50:346–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka R, Gentleman R (1996) R. A language for data analysis and graphics. J Comput Graph Stat 5:299–314 [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T, Mihara M, Suzuki Y, Gupta M, Itoh H, Nagano AJ, Motoyama R, Sawada Y, Yano M, Yokota Hirai M, Makino A, Nagamura Y (2011) Os-GIGANTEA confers robust diurnal rhythms on the global transcriptome of rice in the field. Plant Cell 23:1741–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khozaei M, Fisk S, Lawson T, Gibon Y, Sulpice R, Stitt M, Lefebvre SC, Raines CA (2015) Overexpression of plastid transketolase in tobacco results in a thiamine auxotrophic phenotype. Plant Cell 27:432–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JR, Albery WJ (1977) Perfection in enzyme catalysis: the energetics of triosephosphate isomerase. Acc Chem Res 10:105–111 [Google Scholar]

- Kurzok HG, Feierabend J (1984) Comparison of a cytosolic and a chloroplast triosephosphate isomerase isoenzyme from rye leaves: II. Molecular properties and phylogenetic relationships. Biochim Biophys Acta 788:222–233 [Google Scholar]

- Kyozuka J, McElroy D, Hayakawa T, Xie Y, Wu R, Shimamoto K (1993) Light-regulated and cell-specific expression of tomato rbcS-gusA and rice rbcS-gusA fusion genes in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol 102: 991–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S, Lawson T, Zakhleniuk OV, Lloyd JC, Raines CA, Fryer M (2005) Increased sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase activity in transgenic tobacco plants stimulates photosynthesis and growth from an early stage in development. Plant Physiol 138:451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Weraduwage SM, Preiser AL, Tietz S, Weise SE, Strand DD, Froehlich JE, Kramer DM., Hu J, Sharkey TD (2019) A cytosolic bypass and G6P shunt in plants lacking peroxisomal hydroxypyruvate reductase. Plant Physiol 180:783–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardozzi DL, Smith NG, Cheng SJ, Dukes JS, Sharkey TD, Rogers A, Fisher R, Bonan GB (2018) Triose phosphate limitation in photosynthesis models reduces leaf photosynthesis and global terrestrial carbon storage. Environ Res Lett 13:074025 [Google Scholar]

- McClain AM, Sharkey TD (2019) Triose phosphate utilization and beyond: from photosynthesis to end product synthesis. J Exp Bo 70:1755–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A (2021) Photosynthesis improvement for enhancing productivity in rice. Soil Sci Plant Nutr doi: 10.1080/00380768.2021.1966290 (August 19, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Sage RF (2007) Temperature response of photosynthesis in transgenic rice transformed with ‘sense’ or ‘antisense’ rbcS. Plant Cell Physiol 48:1472–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K (1984) Relation between nitrogen and ribulose-l,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in rice leaves from emergence through senescence. Plant Cell Physiol 25:429–437 [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K (1985) Enzymic properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase purified from rice leaves. Plant Physiol 79:57–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K (1988) Differences between wheat and rice in the enzyme properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and their relationship to photosynthetic gas exchange. Planta 174: 30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Suzuki Y, Yoshizawa R, Kanno K, Makino A (2012) Effect of individual suppression of RBCS multigene family on Rubisco contents in rice leaves. Plant Cell Environ 35:546–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooga T, Sato H, Nagashima A, Sasaki K, Tomita M, Soga T, Ohashi Y (2011) Metabolomic anatomy of an animal model revealing homeostatic imbalances in dyslipidaemia. Mol BioSyst 7:1217–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul MJ, Knight JS, Habash D, Parry MAJ, Lawlor DW, Barnes SA, Loynes A, Gray JC (1995) Reduction in phosphoribulokinase activity by antisense RNA in transgenic tobacco: effect on CO2 assimilation and growth in low irradiance. Plant J 7:535–542 [Google Scholar]

- Paul MJ, Driscoll SP, Andralojc PJ, Knight JS, Gray JC, Lawlor DW (2000) Decrease of phosphoribulokinase activity by antisense RNA in transgenic tobacco: definition of the light environment under which phosphoribulokinase is not in large excess. Planta 211:112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky E, Gottlieb LD (1984) Plant triose phosphate isomerase isozymes: purification, immunological and structural characterization, and partial amino acid sequences. Plant Physiol 74:340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Evans JR, von Caemmerer S, Yu JW, Badger MR (1995) Specific reduction of chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity by antisense RNA reduces CO2 assimilation via a reduction in ribulose bisphosphate regeneration in transgenic tobacco plants. Planta 195: 369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior AF, Tackaberry SE, Aubin AR, Casley LW (2006) Accurate determination of zygosity in transgenic rice by real-time PCR does not require standard curves or efficiency correction. Transgenic Res 15:261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska SA, Andrews TJ, Badger MR, Price GD, von Caemmerer S (2000) The role of chloroplast electron transport and metabolites in modulating Rubisco activity in tobacco. Insights from transgenic plants with reduced amounts of cytochrome b/f complex or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Plant Physiol 122:491–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Kubien DS (2007) The temperature response of C3 and C4 photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 30:1086–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Sharkey TD, Seemann JR (1988) The in-vivo response of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase activation state and the pool sizes of photosynthetic metabolites to elevated CO2 in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Planta 174:407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Takehisa H, Kamatsuki K, Minami H, Namiki N, Ikawa H, Ohyanagi H, Sugimoto K, Antonio B, Nagamura Y (2013) RiceXPro version 3.0: expanding the informatics resource for rice transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D1206–D1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Häusler RE, Kolukisaoglu U, Kunze R, van der Graaff E, Schwacke R, Catoni E, Desimone M, Flügge UI (2002) An Arabidopsis thaliana knock-out mutant of the chloroplast triose phosphate/phosphate translocator is severely compromised only when starch synthesis, but not starch mobilisation is abolished. Plant J 32:685–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD (1985a) Photosynthesis in intact leaves of C3 plants: physics, physiology and rate limitations. Bot Rev 51:53–105 [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD (1985b) O2-insensitive photosynthesis in C3 plants. Plant Physiol 78:71–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD (2019) Discovery of the canonical Calvin-Benson cycle. Photosynth Res 140:235–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Stitt M, Heineke D, Gerhardt R, Raschke K, Heldt HW (1986a) Limitation of photosynthesis by carbon metabolism. II. O2-insensitive CO2 uptake results from limitation of triose phosphate utilization. Plant Physiol 81: 1123–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Seemann JR, Berry JA (1986b) Regulation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase activity in response to changing partial pressure of O2 and light in Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant Physiol 81: 788–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Kobza J, Seemann JR, Brown RH (1988) Reduced cytosolic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase activity leads to loss of O2 sensitivity in a Flaveria linearis mutant. Plant Physiol 86:667–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin AJ, McAusland L, Headland LR, Lawson T, Raines CA (2015) Multigene manipulation of photosynthetic carbon assimilation increases CO2 fixation and biomass yield in tobacco. J Exp Bot 66:4075–4090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin AJ, Lopez-Calcagno PE, Davey PA, Headland LR, Lawson T, Timm S, Bauwe H, Raines CA (2017) Simultaneous stimulation of sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase, fructose 1,6-bisphophate aldolase and the photorespiratory glycine decarboxylase-H protein increases CO2 assimilation, vegetative biomass and seed yield in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotech J 15:805–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin AJ, López-Calcagno PE, Raines CA (2019) Feeding the world: improving photosynthetic efficiency for sustainable crop production. J Exp Bot 70:1119–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga T, Heiger DN (2000) Amino acid analysis by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 72:1236–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga T, Ueno Y, Naraoka H, Ohashi Y, Tomita M, Nishioka T (2002) Simultaneous determination of anionic intermediates for Bacillus subtilis metabolic pathways by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 74:2233–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga T, Ohashi Y, Ueno Y, Naraoka H, Tomita M, Nishioka T (2003) Quantitative metabolome analysis using capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 2:488–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Lunn J, Björn U (2010) Arabidopsis and primary photosynthetic metabolism – more than the icing on the cake. Plant J 61:1067–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganami M, Suzuki Y, Tazoe Y, Yamori W, Makino A (2021) Co-overproducing Rubisco and Rubisco activase enhances photosynthesis in the optimal temperature range in rice. Plant Physiol 185:108–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Kawazu T, Koyama H (2004) RNA isolation from siliques, dry seeds, and other tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana. BioTechniques 37:542–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ohkubo M, Hatakeyama H, Ohashi K, Yoshizawa R, Kojima S, Hayakawa T, Yamaya T, Mae T, Makino A (2007) Increased Rubisco content in transgenic rice transformed with the ‘sense’ rbcS gene. Plant Cell Physiol 48:626–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Nakabayashi K, Yoshizawa R, Mae T, Makino A (2009a) Differences in expression of the RBCS multigene family and Rubisco protein content in various rice plant tissues at different growth stages. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1851–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Miyamoto T, Yoshizawa R, Mae T, Makino A (2009b) Rubisco content and photosynthesis of leaves at different positions in transgenic rice with an overexpression of RBCS. Plant Cell Environ 32:417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Fujimori T, Kanno K, Sasaki A, Ohashi Y, Makino A (2012) Metabolome analysis of photosynthesis and the related primary metabolites in the leaves of transgenic rice plants with increased or decreased Rubisco content. Plant Cell Environ 35:1369–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Kondo E, Makino A (2017) Effects of co-overexpression of the genes of Rubisco and transketolase on photosynthesis in rice. Photosynth Res 131:281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Wada S, Kondo E, Yamori W, Makino A (2019) Effects of co-overproduction of sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase and Rubisco on photosynthesis in rice. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 65:36–40 [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ishiyama K, Sugawara M, Suzuki Y, Kondo E, Takegahara-Tamakawa Y, Yoon DK, Suganami M, Wada S, Miyake C, et al. (2021a) Overproduction of chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase improves photosynthesis slightly under elevated [CO2] conditions in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 62:156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ishiyama K, Cho A, Takegahara-Tamakawa Y, Wada S, Miyake C, Makino A (2021b) Effects of co-overproduction of Rubisco and chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase on photosynthesis in rice. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 67: 283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand Å, Zrenner R, Trevanion S, Stitt M, Gustafsson P, Gardeström P (2000) Decreased expression of two key enzymes in the sucrose biosynthesis pathway, cytosolic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and sucrose phosphate synthase, has remarkably different consequences for photosynthetic carbon metabolism in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 23:759–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Hara N, Ono K, Onodera H, Tagiri A, Oka S, Tanaka H (2006) Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J 47:969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S (2000) Biochemical Models of Photosynthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD (1981) Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 153:376–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada S, Takagi D, Miyake C, Makino A, Suzuki Y (2019) Responses of the photosynthetic electron transport reactions stimulate the oxidation of the reaction center chlorophyll of photosystem I, P700, under drought and high temperatures in rice. Int J Mol Sci 20:2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters RG, Ibrahim DG, Horton P, Kruger NJ (2004) A mutant of Arabidopsis lacking the triose-phosphate/phosphate translocator reveals metabolic regulation of starch breakdown in the light. Plant Physiol 135:891–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka C, Suzuki Y, Makino A (2016) Differential expression of genes of the Calvin–Benson cycle and its related genes during leaf development in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 57:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DK, Ishiyama K, Suganami M, Tazoe Y, Watanabe M, Imaruoka S, Ogura M, Ishida H, Suzuki Y, Obara M, et al. (2020) Transgenic rice overproducing Rubisco exhibits increased yields with improved nitrogen-use efficiency in an experimental paddy field. Nat Food 1:134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Lu Q, Yin Y, Ding S, Wen X, Lu C (2010) Comparative proteomic analysis provides new insights into the regulation of carbon metabolism during leaf senescence of rice grown under field conditions. J Plant Physiol 167:1380–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Long SP, Ort DR (2010) Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61:235–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zrenner R, Krause KP, Apel P, Sonnewald U (1996) Reduction of the cytosolic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in transgenic potato plants limits photosynthetic sucrose biosynthesis with no impact on plant growth and tuber yield. Plant J 9:671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.