Abstract

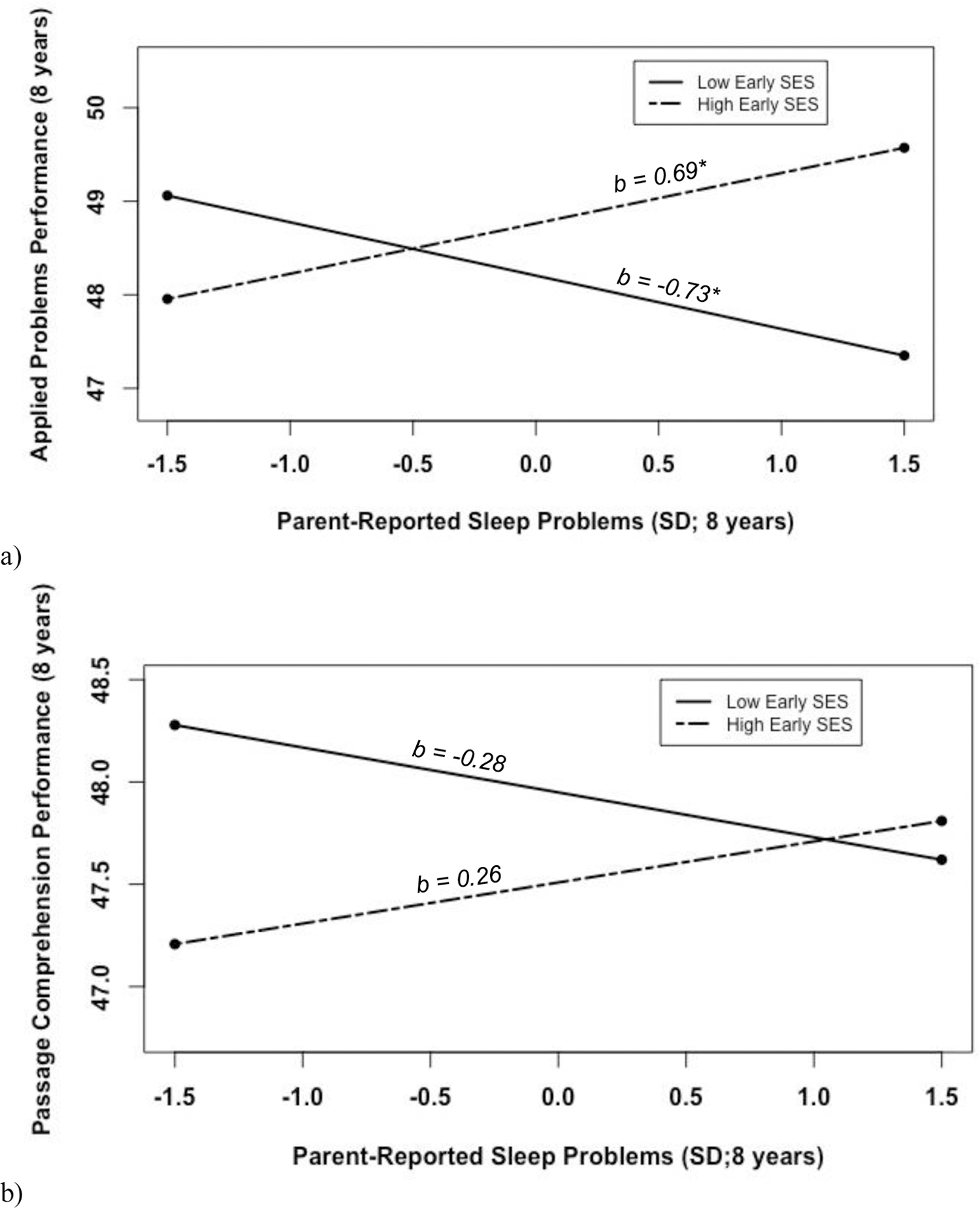

Poor sleep can negatively impact children’s academic performance. However, it is unknown whether early-life socioeconomic status (SES) moderates later sleep and academics. We tested associations between actigraphy-based sleep duration and midpoint time, and parent-reported sleep problems with objective and subjective measures of academic performance. We also examined whether relations varied by early and concurrent SES. Children (n=707; 52% female; Mage=8.44 years; 28.7% Hispanic/Latinx; 29.7% at/below poverty line) were assessed at 12 months for SES and eight years for SES, sleep, and academics. There were no main effects of sleep on academics. More sleep problems predicted lower Applied Problems performance for low SES children (b=−.73, p<.05) and better performance for high SES children (b=.69, p<.05). For high SES children, greater sleep problems (b=−.11, p<.05) and longer sleep duration (b=−.11, p<.05) predicted lower academic achievement. However, most associations were consistent across SES, illustrating the complex interplay between sleep, academic outcomes, and SES.

Keywords: sleep, actigraphy, academic performance, children, middle childhood, socioeconomic status

Studies show that 20–45% of children achieve less than the recommended 9–11 hours of sleep per night (Chaput et al., 2018; Dewald et al., 2010). This is problematic, as shortened sleep duration and low-quality sleep have been associated with impairments across multiple domains, including emotion regulation and cognitive performance (Astill et al., 2012; Sadeh, 2007). In addition, children from low socioeconomic environments experience numerous contextual (e.g., less social support) and systemic (e.g., more violent neighborhoods, fewer community resources) stressors that may interact with poor sleep, in turn leading to worse academic outcomes (Evans, 2005; Jarrin et al., 2014). Although theorists suggest that early life socioeconomic conditions, over and above the role of concurrent environments, have long-lasting effects on children’s development (Chen et al., 2012), it is unknown whether early life socioeconomic status (SES) shapes how sleep and academic achievement are associated in middle childhood. Thus, the goals of this study were to examine the relations between objective and parent-reported sleep parameters (i.e., sleep duration, sleep midpoint time, and sleep problems) and academic performance in middle childhood in a large, socioeconomically diverse sample (Aim 1) and to test whether associations between sleep and academic achievement were moderated by SES measured in infancy (Aim 2) and middle childhood (Aim 3). There is evidence suggesting that sleep interventions improve both sleep habits and academic/cognitive performance in children and adolescents (Dewald-Kaufmann et al., 2013; Gruber et al., 2016; Rey et al., 2020). However, understanding how early and concurrent socioeconomic contexts shape the relations between sleep and academic performance can help target the most effective intervention for each developmental stage. For example, a sleep education program that also provides children with a quality bed is likely to offer more benefits for children from households experiencing financial stress compared to children from high SES households (Mindell et al., 2016).

There are numerous ways to capture the multifaceted nature of sleep, including objective measures of sleep duration (time spent asleep each night), sleep midpoint (the midpoint time between bedtime and waketime which is an indicator of sleep timing, i.e., reflecting how early or late a child goes to bed and wakes up), sleep quality (e.g., sleep efficiency, movement during sleep, how long it takes a child to fall asleep), and subjective measures of sleepiness or occurrences of sleep problems. In our study, we considered sleep duration, sleep midpoint, and parent-reported sleep problems because they assess different aspects of sleep and have been shown to be important for children’s academic and cognitive outcomes (Crowley et al., 2017). Additionally, research has shown that delaying school start times is associated with longer sleep duration, reduced daytime sleepiness, and increased attendance (Troxel & Wolfson, 2017), highlighting the clinical importance of considering sleep duration, timing, and problems.

Sleep and Academic Outcomes

There are several proposed mechanisms explaining why sleep may be important for children’s academic performance. First, sleep is integral in supporting various cognitive processes, including brain maturation, information processing, memory consolidation, and learning (Sadeh, 2007). Imaging studies show that sleep strengthens the horizontal neocortical connections that eventually release memory traces from temporary hippocampus-dependent storage to long-term neocortical storage (Born & Wilhelm, 2012; Sutherland & McNaughton, 2000). In addition, slow wave and rapid eye movement sleep both play a role in learning (see Buckhalt, 2011). Slow wave sleep, characterized by slower frequency, high-amplitude electroencephalogram (EEG) waves, occurs earlier in the sleep period and plays a role in the consolidation of declarative memory (Plihal & Born, 1997). Interestingly, slow wave sleep occurs more frequently in children compared to adults, thus contributing to children’s neuronal plasticity (Brehmer et al., 2007). Rapid eye movement sleep, marked by higher frequency, low-amplitude EEG waves, occurs later in the sleep period and is implicated in the consolidation of emotional and procedural memory (Plihal & Born, 1997). In sum, unique characteristics of sleep, some of which are particularly important during childhood, make this developmental period an especially important time to examine the relation between sleep and adaptive school functioning (Beebe, 2011).

Meta-analyses demonstrate modest relations between measures of sleep and academic performance (Dewald et al., 2010). Specifically, empirical work shows that longer objective sleep duration, measured using actigraphy watches, was associated with better reading achievement longitudinally from 3rd to 5th grade in U.S. children (Buckhalt et al., 2009), and higher math grades in a Canadian sample of girls assessed during late childhood and early adolescence (Lin et al., 2020). In Spanish adolescents, longer objective, but not self-reported, sleep duration was related to better verbal ability (Adelantado-Renau et al., 2019). In a Canadian study, persistent parent-reported short sleep duration, assessed across toddlerhood and childhood, was associated with lower receptive vocabulary at 10 years of age (Seegers et al., 2016). Interestingly, a recent study of Canadian children found that a more rapid decline in objective sleep duration across the preschool period was associated with better math and reading performance in first grade, demonstrating that the development of children’s sleep in early childhood sets the stage for later academic performance (Bernier et al., 2020).

Earlier sleep midpoint, calculated using self-reported bed and wake times, predicted better grades in German and Russian youth (Arbabi et al., 2015; Kolomeichuk et al., 2016), but a similar measure was not associated with school achievement in Italian adolescents (Tonetti et al., 2015). Similarly, parent-reported sleep problems predicted decreased intellectual ability and reading achievement in U.S. children (Buckhalt et al., 2009), and poorer teacher-reported language, literacy, and math ability in Australian children (Quach et al., 2009). Finally, in a Norwegian sample of children, persistent parent-reported sleep problems across middle childhood to early adolescence predicted poorer teacher-reported academic performance (Stormark et al., 2019). Together, the existing literature across several countries demonstrates that multiple dimensions of sleep are related to children’s academic performance, yet more research is needed to understand how these associations might differ based on children’s environments (Buckhalt, 2011).

Role of Family Socioeconomic Status

There is preliminary evidence suggesting the important, but complex, role that SES plays in associations between sleep and academic/cognitive performance in children and adolescents. In a sample of European American and African American children, longer sleep duration was associated with better academic performance for children from high SES homes (Buckhalt et al., 2007). However, when assessed two years later, longer sleep duration predicted higher math performance for children from households with low parental education (Buckhalt et al., 2009). In a similar sample, children from high SES households showed improvements in cognitive functioning from 9–11 years of age regardless of their sleep duration, but surprisingly, children from low SES households showed improvements in cognitive functioning scores across two years when they slept less rather than more at age 9 (Philbrook et al., 2017). Results from a different sample involving German school-aged children showed that greater parent-reported sleep duration was related to lower academic stress, but only for children from low SES backgrounds (Buzek et al., 2019). Together, the literature suggests there is mixed evidence of SES moderation for sleep duration and cognitive/academic performance.

Child-reported sleepiness has consistently been associated with poorer academic and cognitive performance (e.g., Philbrook et al., 2018), but the role of SES has been inconsistent in these associations. For example, a study conducted in the United States found that higher sleepiness predicted lower executive functioning performance in adolescents from families with lower parental education level (Anderson. et al., 2009). However, another study showed that children that had increases in self-reported sleepiness from ages 9–11 showed lower growth in their cognitive performance compared to children that had decreases in sleepiness, and these associations did not vary by SES (Bub et al., 2011). Together, there is some evidence to suggest that family SES is implicated in the relation between children’s sleep and academic performance, yet more research is needed in other racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples to replicate and extend these findings and clarify patterns of results. In doing so, we can better understand the factors that are associated with sleep and academic performance for children from a wide range of backgrounds.

There are several reasons to expect the relations between sleep and academic functioning to vary based on SES. According to the health disparities hypothesis (Carter-Pokras & Baquet, 2002), economically disadvantaged children are exposed to more lifelong stressors compared to children from high SES families, including more chaotic households, poorer access to healthcare, and poorer living conditions, to name a few (Buckhalt, 2011). Developmental theory suggests that resources and experiences available in infancy and early childhood have long-lasting influences on myriad developmental outcomes, over and above the influence of concurrent experiences (Chen & Miller, 2012). Socioeconomic stress, particularly experienced early in life, has been shown to elevate levels of stress hormones, altering the size and structure of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, affecting sleep (Buckley & Schatzberg, 2005) as well as lead to functional differences in learning, memory, and executive functioning (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Therefore, research is needed to better understand how SES, particularly the early life socioeconomic context, shapes how children’s sleep and academic achievement are associated.

Despite reasons to expect moderation via SES, it is unknown whether early life SES moderates the association between sleep and academic achievement in middle childhood. There is initial evidence to suggest that early SES can longitudinally shape the relations between children’s sleep and other childhood outcomes. For example, using the sample considered in this paper, Breitenstein and colleagues (2019) found stronger associations between multiple objective sleep parameters and weight-related outcomes during middle childhood for children from lower early-life SES backgrounds. Together, these findings suggest SES has lasting implications across multiple domains of children’s functioning. Thus, it is possible that early SES could play a role in the association between sleep and academic outcomes in middle childhood.

Current Study

Several gaps remain in the literature on associations between children’s sleep and academic performance. Although previous studies have examined the role of sleep in children’s academic performance (Dewald et al., 2010), it is unclear whether the relation between sleep and academic performance holds for other groups of children of different ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts. Additionally, in several prior studies, SES was examined as a covariate or concurrent predictor of children’s sleep or academic functioning, but patterns are unclear and it is unknown whether early SES moderates the association between sleep and academic performance later in childhood. Importantly, it is theorized that the role of SES changes across development (Chen & Miller, 2012; Kuh et al., 2003), thus it is possible that early childhood could be a sensitive period where the early environment has a large and lasting influence on the relations between children’s sleep and developmental outcomes.

There were several goals of the study. First, we examined the associations between objective (actigraphy-based) sleep duration, midpoint time, and subjective (parent-reported) sleep problems and assessments of academic performance in middle childhood (Aim 1). We hypothesized negative associations between shorter sleep duration, later timing, and more sleep problems with academic performance (Buckhalt et al., 2007; 2009). The main goal of our study was to examine whether early life SES, beyond the effect of current SES, moderated links between sleep duration, midpoint time, and parent-reported sleep problems with academic performance (Aim 2). Based on empirical work demonstrating the effect of concurrent SES on children’s sleep and academic achievement (Buckhalt et al., 2009) and theoretical models positing the long-lasting effects of early SES on children’s later development (Chen & Miller, 2012), we hypothesized that associations between sleep and academic achievement would be stronger for children that experienced low early SES. Third, to replicate and extend prior literature (Buckhalt, 2011), we also tested the effect of concurrent SES as a moderator of associations between sleep and academic performance (Aim 3). All aims were addressed in our socioeconomically- and racially-diverse community sample of children.

Finally, testing linear associations assumes that the rate of change in an outcome is constant across all levels of the predictor (Cohen et al., 2002). However, it is possible that academic performance is maximized at particular levels of sleep duration, midpoint, and problems. In fact, El-Sheikh and colleagues (2019) found a significant quadratic association between child-reported sleep problems and academic achievement, such that relations were initially flat but became increasingly negative with increasing sleep problems. To explore this possibility further, sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine quadratic associations between sleep duration, midpoint, and problems and academic performance.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Arizona Twin Project, an ongoing longitudinal twin study (Lemery-Chalfant et al., 2013; 2019). The use of a twin data set to address research questions that do not require a twin sample is consistent with other work, as twins are shown to be representative of singleton children across many traits and developmental outcomes (Barnes & Boutwell, 2013), including early temperament (Goldsmith et al., 1999) and cognitive abilities (Posthuma et al., 2000). Additionally, descriptive statistics for key variables in our study are comparable to published studies based on samples of singletons (Buckhalt et al., 2009).

Families were recruited from birth records when the twins were approximately 12 months old. Of the 401 families that opted to contact us, 329 families (82.29%) participated at 12 months of age. Of the 329 families that participated at 12 months, 263 families participated at the 8-year wave. The current analytic sample comprised 707 children, (Mage = 8.44 years; SD = .69; data collected from 2016 to 2018) and included 258 families (78%) that participated at 12 months, and 94 families were newly recruited at 8 years of age.

Not included in the final sample are 9 individuals who were excluded prior to analyses due to physical or cognitive disabilities, but none of these had diagnosed sleep disorders. The current analytic sample was 51.6% female and comprised 30.2% monozygotic (MZ), 37.8% same-sex dizygotic (DZ), and 32.0% opposite-sex DZ twins. The participants were 28.7% Hispanic/Latino, 56.5% European American, 3.4% Asian American, 3.7% African American, and 7.7% multiethnic or other. Attrition analyses indicated no significant differences between the 12-month and 8-year sample on sex, t(269) = −.40, p = .69. However, there were significantly fewer Latinx families with 8-year data (M = .20, SD = .40) than families without (M = .32, SD = .47), t(269) = 2.22, p = .03, and early SES was significantly higher in the sample of families with 8-year data (M = .17, SD = .75) than the families without (M = −.16, SD = .80), t(267) = −3.49, p = .001.

Procedure

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at every wave of data collection. When the twins were 12 months of age, primary caregivers (95.8% mothers) completed telephone interviews about their demographic information, parenting and their twins’ health and development. Two home visits were conducted at the 8-year wave of data collection. Primary caregivers (94.7% mothers) provided written informed consent and twins assented to participation. At the first home visit, each child was instructed to wear an actigraph watch for seven continuous nights. During the study week, the primary caregiver recorded their children’s daily wake and bedtimes on a daily assessment table, and completed a daily diary assessing their children’s previous night of sleep. In addition, the primary caregiver completed a questionnaire assessing demographic information and their children’s sleep problems and academic achievement. At the second home visit, the actigraph watches were collected and a trained research assistant administered the Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Achievement as an objective measure of academic performance.

Measures

Objective sleep

Children’s objective sleep was measured using wrist-based accelerometers (actigraph watches) (Motion Logger Micro Watch; Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY, USA). The watches were worn on non-dominant wrists for seven nights (Mnights = 6.79). The Action-W 2 program (version 2.7.1) was used to score actigraphy data, including a validated algorithm that measured sleep (Sadeh et al., 1994). Nighttime sleep duration (total number of hours and minutes asleep each night between sleep onset and offset and waking excluding wake bouts) and sleep midpoint time (the midpoint time in between bedtime and waketime) was calculated. Trained research assistants cross-validated objective actigraph sleep periods with parent-reported bed and wake times to identify significant outliers and equipment malfunction. Sleep data were missing or excluded from analyses for 67 children (12.4%) due to children not wearing the watch during the study week or watch malfunction (e.g., watch submerged in water, broken, etc.). However, over 80% in our sample wore the actigraph watch for seven or more nights, indicating high compliance with actigraph study procedures (for more details, see Doane et al., 2019).

Sleep problems

Primary caregivers used the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Owens et al., 2000) to report on their children’s sleep difficulties (α = .81). This 35-item measure assesses sleep duration problems, bedtime resistance, sleep latency, nighttime wakings, sleep anxiety, parasomnias, sleep disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness. Primary caregivers rated their children from 1 (Always) to 5 (Never), and an average score was created such that higher scores indicated greater sleep disturbances.

Academic achievement

Children were administered the Picture Vocabulary, Passage Comprehension, and Applied Problems subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Achievement (Schrank et al., 2014). Picture Vocabulary measures word knowledge, Passage Comprehension assesses understanding of written text, and Applied Problems tests children’s ability to analyze and solve math problems. A W score was calculated for each subtest, with higher scores representing better academic achievement (Villarreal, 2015). The W score is based on a transformation of the Rasch ability scale that provides a common scale of equal-interval measurement representing both the child’s ability and the task’s difficulty. Scores are centered on a value of 500, which is equivalent to the average performance at age 10 years, 0 months (Mather & Jaffe, 2016). These assessments are used extensively and have strong psychometric properties (Schrank et al., 2014).

Primary caregivers reported on their children’s academic achievement using the Health and Behavior Questionnaire (Armstrong & Goldstein, 2003). The scale consisted of 5 items assessing their children’s academic performance (e.g., How would you describe Twin A/B’s current school performance overall?). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Poor; well below grade level, 2 = Needs improvement; below average for grade level, 3 = Satisfactory; at grade level, 4 = Very good; above average for grade level, 5 = Excellent; well above grade level). Scores on this scale were mean composited, with higher scores indicating greater academic achievement (α = .91).

Socioeconomic status (SES)

When twins were 12 months old (i.e., between 2008 and 2009), participants provided information on their SES. Specifically, the education of both the primary caregiver and his or her spouse/partner was reported. The response categories included: (1) less than high school; (2) high school or equivalent; (3) Some college, not graduated; (4) college degree (e.g., BA, BS); (5) Two or more years of graduate school; (6) graduate or professional degree. Primary caregivers also disclosed their total household income, prior to taxes. The response categories included: (1) less than $30,001; (2) $30,0001-$40,000; (3) $40,001-$50,000; (4) $50,001-$60,000; (5) $60,001-$70,000; (6) $70,001-$80,000; (7) $80,001-$90,000; (8) $90,001-$100,000; (10) $100,001-$150,000; (11) More than $150,001. Income-to-needs scores were calculated based on family household income, the number of individuals in the household supported by that income, and the federal poverty standards published for 2009. The mean of the family income range was divided by the federal poverty threshold for the household size. Families were considered to be a) living in poverty if they received a score of <1 (10.4% of sample); b) near the poverty line if they scored 1–2 (20.9% of sample); c) lower middle class if they scored 2–3 (23.9%); d) middle to upper class if they scored greater than a 3 (44.8%). We created a standardized composite including income-to-needs ratio, and primary caregiver and secondary caregiver education level. The SES composite was also computed for each family at the eight-year assessment using the same variables and process. More specifically, 7.4% of families were below the poverty line, 22.3% were near the poverty line, 16.3% were considered lower middle class, and 54.0% were considered middle to upper class (for more details, see Doane et al., 2019).

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex (female = 1), race (non-Hispanic White = 1), SES at 8 years of age, body mass index (BMI), and whether the study was completed during a school vacation or not (study completed during a vacation = 1), as these are variables known to relate to sleep or academic outcomes (Breitenstein et al., 2019; Buckhalt et al., 2007; Buzek et al., 2019; Sousa et al., 2009). After adjusting for age and sex, BMI was calculated using the child BMI formula (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021): weight (kg)/[height (m)]2. Covariates were included in all models, regardless of significance.

Analytic Plan

Scores on key variables that were +/− 3 SDs from the mean were winsorized to 3 SD from the mean. A linear transformation was applied to scores on Applied Problems, Passage Comprehension, and Picture Vocabulary variables (scores were divided by 10) to reduce the amount of variance in the model, thus facilitating model convergence (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Mixed model regression analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). With early SES as a moderator (controlling for concurrent SES), interactions were individually tested while estimating the main effects of all sleep parameters on academic performance. Separate models were also conducted when testing moderation by concurrent SES (not controlling for early SES). The type=complex command was used to account for twin interdependence, and full information maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to handle missing data (Muthén & Kaplan, 1985). Predictors, moderators, and covariates were centered at zero and were used to create interaction terms. Unstandardized beta coefficients and standard errors were reported. Simple slopes from significant interactions were probed at 1 SD below and above the mean of early SES using the approach advanced by Preacher and colleagues (Preacher. et al., 2006) for nested data. Results are reported by each aim.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are reported in Table 1. The average sleep hours per night based on actigraphy was 8.12 hours (SD = .73 or 43.8 minutes). Although sleep duration was unrelated to the measures of academic performance, sleep midpoint time was negatively correlated with Picture Vocabulary and parent-reported academic achievement. Parent-reported sleep problems were negatively correlated with Picture Vocabulary, Applied Problems, Passage Comprehension, and parent-reported academic achievement. Early and concurrent SES were positively correlated with sleep duration, Picture Vocabulary, Applied Problems, Passage Comprehension, and parent-reported academic achievement, and negatively correlated with sleep midpoint time, and parent-reported sleep problems. Additionally, early and concurrent SES were positively correlated.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Objective Nighttime Sleep Duration (hours) | - | |||||||||||||

| 2. Objective Sleep Midpoint Time | −.19*** | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Parent-reported Sleep Problems | −.15** | .18** | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Picture Vocabulary | .05 | −.17** | −.16** | - | ||||||||||

| 5. Applied Problems | −.02 | −.04 | −.12* | .54*** | - | |||||||||

| 6. Passage Comprehension | .07 | −.04 | −.11* | .59*** | .61*** | - | ||||||||

| 7. Parent-Reported Academic Achievement | .10 | −.15** | −.15** | .36*** | .44*** | .49*** | - | |||||||

| 8. Early SES | .23*** | −.23*** | −.18** | .27*** | .19*** | .19** | .29*** | - | ||||||

| 9. Concurrent SES | .21*** | −.16** | −.20*** | .34*** | .27*** | .27*** | .31*** | .83*** | - | |||||

| 10. Age (years) | −.23*** | .24*** | .01 | .21*** | .36*** | .33*** | −.05* | −.19** | −.09 | - | ||||

| 11. Race/Ethnicity | .15** | −.19** | −.04 | .16*** | .04 | .13* | .06 | .26*** | .24*** | −.19*** | - | |||

| 12. Sex | .16*** | .04 | .02 | .03 | −.15** | .01 | .01 | −.01 | .05 | .01 | −.05 | - | ||

| 13. BMI | −.18*** | .04 | .05 | −.03 | .02 | −.06 | −.12* | −.16*** | −.12** | .13*** | −.13*** | .02 | - | |

| 14. Vacation | −.01 | .30*** | −.09 | −.06 | −.03 | −.08 | −.03 | −.01 | .05 | −.01 | −.01 | −.02 | .01 | - |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mean | 8.12 | 2:13 AM | 1.74 | 483.72 | 483.90 | 476.17 | 3.82 | .00 | .00 | 8.44 | .59 | .52 | 16.76 | .27 |

| Standard Deviation | .73 | 46 min | .35 | 10.15 | 20.30 | 16.44 | .87 | .80 | .81 | .69 | - | - | 2.91 | - |

| Minimum | 4.46 | 12:18 AM | 1.00 | 452.00 | 419.00 | 353.00 | 1.20 | −2.05 | −1.72 | 6.96 | - | - | 12.11 | - |

| Maximum | 10.26 | 4:46 AM | 3.29 | 519.00 | 531.00 | 512.00 | 5.00 | 1.76 | 3.34 | 10.26 | - | - | 34.92 | - |

| Skewness | −.68 | .67 | .71 | −.02 | −.44 | −1.54 | −.41 | −.15 | .54 | −.18 | - | - | 1.99 | - |

| Kurtosis | 1.75 | .57 | .89 | .22 | −.42 | 6.05 | −.55 | −.55 | .42 | −.36 | - | - | 5.92 | - |

Note. N = 707. Sex (1 = female), ethnicity (1 = non-Hispanic White), BMI = body mass index; SES = socioeconomic status. Vacation (1 = study completed during summer or school vacation).

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Parent-reported sleep problems were assessed using the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Parent-reported academic achievement was assessed using the Health and Behavior Questionnaire.

Primary Analyses

Main effects

Table 2 includes the main effects of sleep duration, midpoint, and problems on academic performance, as well as early SES as a moderator of these associations. There were no significant main effects of sleep duration, midpoint, and problems on academic performance. Early SES did not predict academic performance.

Table 2.

Objective and subjective sleep indicators predicting academic outcomes in middle childhood moderated by early SES.

| Model Predictors | Picture Vocabulary | Applied Problems | Passage Comprehension | Academic Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Est(SE) | Est(SE) | Est(SE) | Est(SE) | |

| Intercept | 48.41(.09)*** | 48.46(.11)*** | 47.72(.08)*** | 3.82(.04)*** |

| Sex | −0.05(.08) | −0.78(.14)*** | −0.10(.11) | −0.08(.06) |

| Ethnicity | 1.06(.54) | 0.82(.47) | 0.88(.35) * | 0.06(.11) |

| Age | 0.95(.39) * | 1.67(.35) *** | 1.13(.26) *** | 0.09(.09) |

| Vacation | −1.02(.73) | −0.93(.61) | −0.82(.46) | −0.22(.13) |

| BMI | 0.03(.02) | 0.02(.03) | −0.01(.02) | −0.04(.02)* |

| Early SES | −0.52(1.06) | −0.51(.95) | −0.41(.70) | 0.02(.19) |

| Concurrent SES | 2.02(1.25) | 2.20(1.08) * | 1.54(.79) | 0.49(.18) ** |

| Sleep Duration (hrs) | −0.03(.06) | 0.01(.10) | 0.10(.08) | −0.02(.04) |

| Sleep Duration x Early SES | −0.01(.04) | −0.17(.12) | −0.02(.07) | −0.11(.03)** |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | 48.41(.09)*** | 48.46(.11)*** | 47.72(.08)*** | 3.82(.04)*** |

| Sex | −0.04(.08) | −0.79(.14)*** | −0.10(.11)*** | −0.10(.06) |

| Ethnicity | 1.05(.54) | 0.83(.47) | 0.89(.35)* | 0.06(.11) |

| Age | 0.95(.39) * | 1.67(.35) *** | 1.13(.26) *** | 0.09(.09) |

| Vacation | −1.04(.73) | −0.94(.62) | −0.84(.46) | −0.22(.13) |

| BMI | 0.03(.01) | 0.02(.03) | 0.01(.02) | −0.04(.02)* |

| Early SES | −0.51(1.06) | −0.51(.95) | −0.39(.70) | 0.02(.19) |

| Concurrent SES | 2.01(1.24) | 2.20(1.08) * | 1.54(.79) | 0.49(.18) ** |

| Sleep Midpoint Time | 0.19(.15) | 0.17(.15) | 0.17(.11) | 0.01(.05) |

| Sleep Midpoint Time x Early SES | 0.04(.07) | −0.02(.29) | −0.10(.08) | 0.05(.06) |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | 48.41(.09)*** | 48.46(.11)*** | 47.72(.08)*** | 3.82(.04)*** |

| Sex | −0.04(.08) | −0.76(.14)*** | −0.09(.11) | −0.10(.06) |

| Ethnicity | 1.05(.54) | 0.82(.47) | 0.88(.35) * | 0.06(.11) |

| Age | 0.95(.39) * | 1.67(.35) *** | 1.30(.26) *** | 0.09(.09) |

| Vacation | −1.03(.73) | −0.95(.62) | −0.83(.46) | −0.21(.13) |

| BMI | 0.03(.02) | 0.03(.03) | 0.01(.02) | −0.04(.02)** |

| Early SES | −0.50(1.05) | −0.53(.96) | −0.41(.70) | 0.01(.20) |

| Concurrent SES | 2.01(1.24) | 2.24(1.08) * | 1.55(.79) * | 0.48(.19) ** |

| Sleep Problems | −0.06(.20) | −0.02(.27) | −0.01(.19) | −0.11(.12) |

| Sleep Problems x Early SES | −0.01(.12) | 0.88(.24) *** | 0.33(.16) * | −0.43(.11)*** |

Note. All models were conducted independently. Covariates, predictors, and moderator were grand mean centered. Sex (1 = female), ethnicity (1 = non-Hispanic White), Vacation (1 = study completed during summer or school vacation). BMI = body mass index, SES = socioeconomic status. Early SES was assessed at 12 months of age and concurrent SES was assessed at 8 years of age. Est. = unstandardized partial regression coefficient estimate. SE = robust standard error.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Sleep X early-life SES predicts Picture Vocabulary

There were no significant interactions between sleep duration, midpoint, and problems with early SES when predicting Picture Vocabulary.

Sleep X early-life SES predicts Applied Problems

The association between sleep duration and sleep midpoint with Applied Problems did not vary by early SES. Parent-reported sleep problems significantly interacted with early SES to predict performance on Applied Problems (Figure 1a), such that more parent-reported sleep problems were associated with lower performance for children that experienced low early SES (b = −.73, p < .05) and better performance for children that experienced high early SES (b = .69, p < .05). Regions of significance suggested that the association between parent-reported sleep problems and Applied Problems performance were significant for 42.7% of the sample (n = 188).

Figure 1.

a.) Simple slopes plot for Applied Problems performance by parent-reported sleep problems for high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of early SES. b.) Simple slopes plot for Passage Comprehension performance by parent-reported sleep problems for high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of early SES. c.) Simple slopes plot for parent-reported academic achievement by sleep duration for high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of early SES. d.) Simple slopes plot for parent-reported academic achievement by parent-reported sleep problems for high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of early SES. *p < .05.

Sleep X early-life SES predicts Passage Comprehension

There were no significant interactions between sleep duration, midpoint, and problems with early SES when predicting Passage Comprehension. There was a significant interaction between parent-reported sleep problems and early SES predicting Passage Comprehension performance (Figure 1b), but when probed, simple slopes were nonsignificant (low early SES: b = −.28, p = .19; high early SES: b = .26, p = .29).

Sleep X early-life SES predicts Academic Achievement

There was a significant interaction between sleep duration and early SES predicting parent-reported academic achievement (Figure 1c), such that longer sleep duration predicted lower academic achievement for children that experienced high early SES (b = −.11, p < .05), but not for children that experienced low early SES (b = .06, p = .15). Regions of significance suggested that the association between sleep duration and parent-reported academic achievement were significant for 22.3% of the sample (n = 98). Sleep midpoint and parent-reported academic achievement did not vary by early SES. Finally, greater parent-reported sleep problems were associated with poorer parent-reported academic achievement (Figure 1d) for children that experienced high early SES (b = −.11, p < .05) but not for children that experienced low early SES (b = .24, p = .11). Regions of significance suggested that the relations between parent-reported sleep problems and parent-reported academic achievement were significant for 38.2% of the sample (n=168).

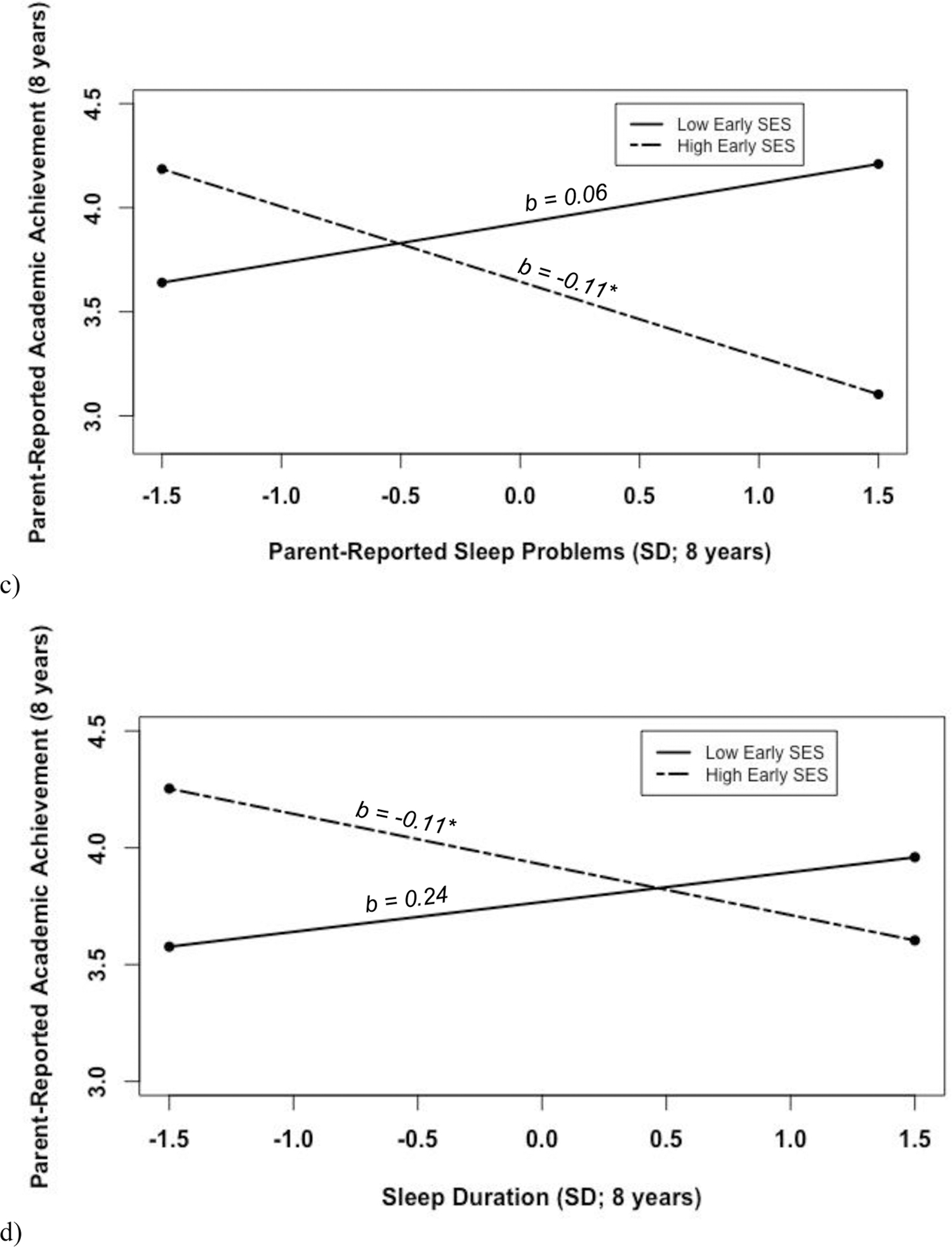

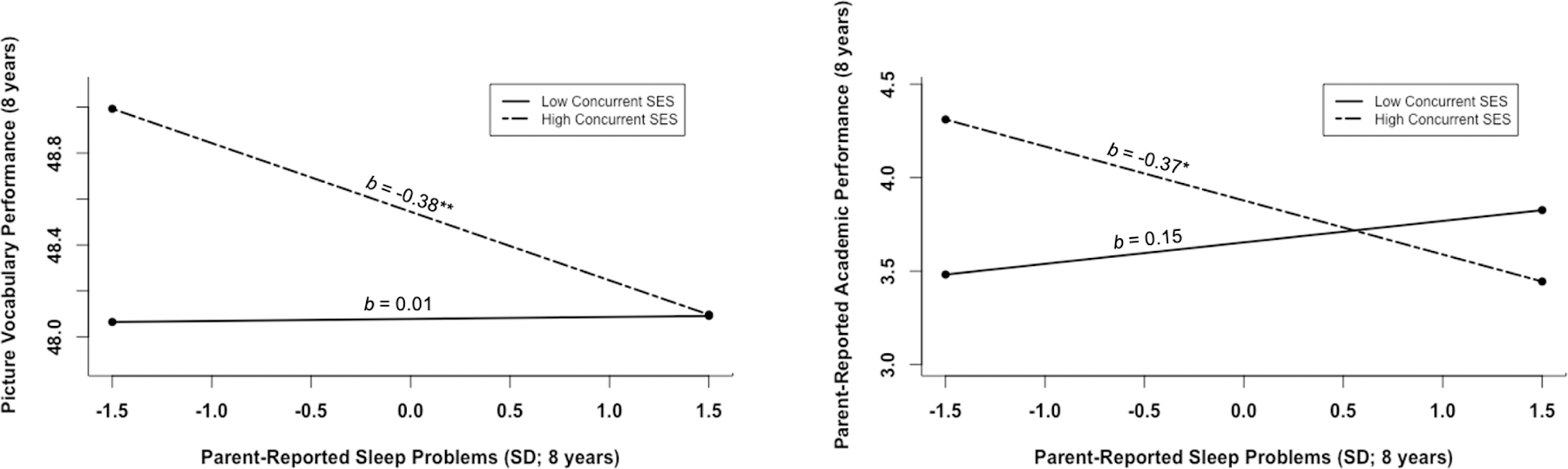

Moderation by Concurrent SES

To replicate and extend prior research, separate models were tested to examine the relation between sleep duration, midpoint, and problems and academic outcomes moderated by concurrent SES (Table 3). Concurrent SES was significantly associated with all outcome measures. In these models, the association between parent-reported sleep problems and Picture Vocabulary was moderated by concurrent SES, such that greater parent-reported sleep problems were associated with lower Picture Vocabulary scores for children from high (b = −.38, p < .01), but not from low SES backgrounds (b = .01, p = .93, see Figure 2a). Region of significance suggests that associations between parent-reported sleep problems and Picture Vocabulary scores were significant for 37% of the sample (n = 250). Concurrent SES also moderated the association between parent-reported sleep problems and parent-reported academic achievement, such that greater sleep problems were related to lower parent-reported academic achievement for children from high (b = −.37, p < .05) but not low SES homes (b = .15, p = .25, see Figure 2b). Region of significance suggests that associations between parent-reported sleep problems and parent-reported academic achievement were significant for 33.5% of the sample (n = 228).

Table 3.

Objective and subjective sleep indicators predicting academic outcomes in middle childhood moderated by concurrent SES.

| Model Predictors | Picture Vocabulary | Applied Problems | Passage Comprehension | Academic Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Est(SE) | Est(SE) | Est(SE) | Est(SE) | |

| Intercept | 48.39(.09) *** | 48.46(.11) *** | 47.72(.08) *** | 3.82(.04) *** |

| Sex | −0.05(.09) | −0.79(.14)*** | −0.10(.11) | −0.09(.06) |

| Ethnicity | 1.00(.49) * | 0.77(.44) | 0.83(.32) * | 0.05(.11) |

| Age | 0.99(.43) * | 1.70(.38) *** | 1.16(.28) *** | 0.09(.08) |

| Vacation | −0.99(.71) | −0.90(.61) | −0.80(.45) | −0.22(.13) |

| BMI | 0.03(.02) * | 0.03(.03) | 0.01(.02) | −0.04(.02)* |

| Concurrent SES | 1.61(.64) * | 1.81(.54) ** | 1.22(.39) ** | 0.51(.09) *** |

| Sleep Duration (hrs) | −0.04(.06) | 0.03(.10) | 0.08(.07) | −0.01(.04) |

| Sleep Duration x Concurrent SES | −0.05(.07) | −0.05(.11) | −0.06(.07) | −0.06(.05) |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | 48.39(.09) *** | 48.46(.11) *** | 47.71(.07) *** | 3.82(.04) *** |

| Sex | −0.04(.08) | −0.79(.14)*** | −0.10(.11) | −0.10(.06) |

| Ethnicity | 1.02(.54) | 0.76(.44) | 0.84(.32) * | 0.05(.11) |

| Age | 1.00(.44) * | 1.67(.38) *** | 1.16(.28) *** | 0.08(.09) |

| Vacation | −0.96(.70) | −0.90(.61) | −0.80(.45) | −0.23(.13) |

| BMI | 0.03(.02) * | 0.02(.03) | 0.01(.02) | −0.04(.02)* |

| Concurrent SES | 1.61(.64) * | 1.81(.54) ** | 1.23(.40) ** | 0.51(.09) *** |

| Sleep Midpoint Time | 0.17(.14) | 0.19(.15) | 0.19(.11) | 0.01(.05) |

| Sleep Midpoint Time x Concurrent SES | −0.13(.10) | 0.06(.11) | −0.14(.08) | 0.03(.06) |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | 48.39(.09) *** | 48.46(.09) *** | 47.72(.06) *** | 3.81(.04) *** |

| Sex | 0.05(.07) | −0.73(.15)*** | −0.06(.11) | −0.09(.06) |

| Ethnicity | 0.24(.10) * | 0.09(.19) | 0.33(.12) ** | −0.09(.08) |

| Age | 0.41(.08) *** | 1.27(.15) *** | 0.85(.10) *** | −0.01(.06) |

| Vacation | −0.13(.12) | −0.04(.21) | −0.15(.14) | −0.05(.08) |

| BMI | 0.01(.01) | 0.02(.03) | −0.01(.02) | −0.04(.02)** |

| Concurrent SES | 0.39(.06) *** | 0.74(.12) *** | 0.43(.07) *** | 0.27(.05) *** |

| Sleep Problems | −0.19(.13) | −0.17(.38) | −0.12(.28) | −0.11(.11) |

| Sleep Problems x Concurrent SES | −0.24(.02)*** | 0.04(.15) | 0.11(.06) | −0.32(.08)*** |

Note. All models were conducted independently. Covariates, predictors, and moderator were grand mean centered. Sex (1 = female), ethnicity (1 = non-Hispanic White), Vacation (1 = study completed during summer or school vacation). BMI = body mass index, SES = socioeconomic status. Concurrent SES was assessed at 8 years of age. Est. = unstandardized partial regression coefficient estimate. SE = robust standard error.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Figure 2.

a.) Simple slopes plot for Picture Vocabulary by parent-reported sleep problems for high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of concurrent SES. b.) Simple slopes plot for Picture Vocabulary by parent-reported sleep problems for high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of concurrent SES. *p < .05; **p < .01

Sensitivity analyses

There was a significant quadratic association between sleep midpoint with Picture Vocabulary (b = −.28, p < .01). More specifically, Picture Vocabulary performance was higher at early (−1 SD) and late (+1 SD) sleep midpoints (47.74 and 48.04, respectively) than mean midpoint (47.65). There was also a significant quadratic association between sleep midpoint with Passage Comprehension (b = .18, p < .01). Like Picture Vocabulary, early and late sleep midpoint was related to higher Passage Comprehension performance (47.66 and 47.68, respectively), with lower performance at mean sleep midpoint time (47.65). Finally, there was a significant quadratic association between sleep duration and parent-reported Academic Achievement (b = −.07, p < .01). More specifically, parent-reported Academic Achievement was lower at shorter (−1 SD) and longer (+1 SD) sleep duration (3.81 and 3.73, respectively) than mean sleep duration (3.85). However, differences in academic performance across the range of sleep were small.

Discussion

This study examined whether SES, measured at 12 months and 8 years of age, moderated associations between actigraphy-based sleep duration, midpoint time, and parent-reported sleep problems with assessments of academic performance in a representative community sample of twin children in middle childhood. There were no main effects of sleep on academic performance. We hypothesized that early and concurrent SES would moderate associations between sleep and academic performance. However, most relations between sleep and academic performance did not vary by SES, suggesting that normal range variation in sleep behaviors might not have a sizable impact on children’s academic performance across SES groups.

Associations Between Sleep and Academic Performance

The first aim of our study was to examine linear associations between sleep and academic performance. Contrary to our hypotheses, we found no linear main effects of both objective and subjective measures of sleep on academic performance, differing from studies that show modest associations between sleep with academic and cognitive performance (e.g., Arbabi et al., 2015; Buckhalt et al., 2007; 2009; Quach et al., 2009; Seegers et al., 2016). Some community samples of children and adolescents have shown that that objective sleep duration was not predictive of academic and cognitive performance (Adelantado-Renau et al., 2019; Nixon et al., 2008), thus it is possible that our large community sample of twins represents normal-range variation in sleep behaviors, and associations with academic performance are only apparent at the extremes of sleep behaviors. There is evidence to suggest that across childhood, children with symptoms of sleep disorders show poorer academic performance (Siva Kumar et al., 2021; Williamson et al., 2020). However, more research is needed, as systematic reviews suggest that effect sizes are small (i.e., academic performance is in the normal range) (Cardoso et al., 2018).

It is also possible that sleep and academic performance are related in nonlinear ways. In our study, sensitivity analyses suggested that both early and late sleep timing predicted better Picture Vocabulary and Passage Comprehension. We also found that shorter and longer sleep duration was associated with lower parent-reported academic achievement. Differences in academic performance scores across the range of sleep in our study were very small, and therefore should be interpreted with caution. Regardless, our study contributes to recent work suggesting sleep duration and quality as nonlinear predictors of children’s cognitive ability (El-Sheikh et al., 2019) and adolescent academic performance (Fuligni et al., 2018). Examining nonlinear associations between sleep and children’s functioning has important public health implications, as identifying the optimal amount, timing, and quality of sleep not only improves children’s physical health, but can also help children maximize their academic performance (James & Hale, 2017).

Moderation of Sleep and Academic Performance by Early SES

The main goal of our study (Aim 2) was to examine whether early life SES, measured in infancy, moderated links between sleep and academic performance in middle childhood. We found some evidence supporting our hypothesis that associations between sleep and academics would be stronger for children from low early SES backgrounds (Buckhalt, 2011), as well as some unexpected links for children from high early SES homes. To begin, we found that greater parent-reported sleep problems were associated with lower Applied Problems performance for children from low early SES backgrounds. There was also a significant interaction between parent-reported sleep problems and early life SES predicting Passage Comprehension. Although the simple slopes did not reach conventional levels of significance, they suggested that greater parent-reported sleep problems predicted poorer Passage Comprehension performance for children from low early SES backgrounds, and higher performance for children from high early SES households. Together, these results are in-line with research suggesting that poor sleep negatively impacts children from low SES backgrounds to a greater degree than children from high SES homes (Buckhalt, 2011; Buckhalt et al., 2007; 2009) as well as with developmental theory positing that the number of resources available in early life have long-lasting influences on children’s development over and above the influence of current experiences (Chen & Miller, 2012).

On the other hand, our findings suggest that with fewer sleep problems, children from low SES households show better Applied Problems and Passage Comprehension performance. Chen and Miller (2012) proposed the “shift-and-persist” model to explain why some children thrive, even amid adversity. The authors suggest that specific strategies (i.e., finding a positive role model, fostering self-regulatory behaviors, focusing on the future) could mitigate the sympathetic-nervous-system and HPA responses to stressors that children from low SES backgrounds face, allowing youth to accept and endure through stressful experiences (Chen & Miller, 2012). Research shows that sleep disruption is related to hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis (HPA axis) activation whereas sleep initiation and slow wave sleep are related to HPA suppression (Buckley & Schatzberg, 2005), suggesting that sleep behaviors, such as obtaining better quality sleep, could be one way the body uses allostasis to respond to stressful conditions (McEwen & Gianaros, 2010). It is possible that improving sleep could be another strategy in which the body maintains homeostasis, allowing children from disadvantaged backgrounds to thrive academically. In fact, school-based intervention studies in elementary-aged children and adolescents have provided initial evidence that sleep education programs improve both sleep behaviors and academic performance (Dewald-Kaufmann et al., 2013; Gruber et al., 2016; Rey et al., 2020), however more research is needed to evaluate the extent that intervention effects on sleep and academics persist.

We also found several significant associations between parent-reported sleep problems and academic performance for children from high early SES backgrounds. First, more sleep problems and longer sleep duration predicted lower parent-reported academic achievement in children from high early SES backgrounds. It is possible that parents in high SES households are more in-tune with their children’s day-to-day experiences, including their academic difficulties. This explanation is in line with evidence that high SES families tend to enforce more consistent bedtime routines (Hale et al., 2009), and other research demonstrating that higher parental involvement and monitoring was related to increased academic socialization for high SES families (Benner et al., 2016). Additionally, parents from high early SES households could also have higher educational expectations for their children (Stull, 2013), thus, children that obtain more sleep could be perceived as not performing as well academically or not as committed to their education. Consistent with this idea, a study involving 8–12-year-old children found that parents with higher educational backgrounds had higher expectations for their children to perform well in mathematics (Bicer et al., 2013) and another study examining children and adolescents across all grades suggested that parents from high SES backgrounds held higher expectations for their child to graduate from high school, compared to families from low SES backgrounds (Zhang et al., 2011). We also found that higher parent-reported sleep problems were associated with better Applied Problems performance for children that experienced high early SES, providing further potential evidence that there could be higher educational expectations for these children at the expense of obtaining sufficient sleep. This is consistent with research demonstrating that many children and adolescents from higher SES backgrounds are under immense pressure to succeed academically, putting them at-risk for later adjustment problems (Luthar & Latendresse, 2005). More research is needed to better understand the association between parental educational expectations and children’s sleep.

We hypothesized that associations between sleep and academic performance would vary by early life SES, based on previous work asserting that associations between sleep and academics were stronger for children from low, compared to high, SES backgrounds (Buckhalt, 2011). Although we provide some evidence for differential associations between sleep and academic performance by early socioeconomic context, it should be noted that only 4 of the 12 tested interactions were significant. This was surprising, given the vast health and education inequities that exist in the United States, as well as literature showing that socioeconomic context is implicated in relations between sleep with other outcomes, including obesity (Buzek et al., 2019) and internalizing and externalizing problems (El-Sheikh et al., 2020). Additionally, another study with our sample showed that links between sleep and weight were strongest for children from low early SES households (Breitenstein et al., 2019), together highlighting the complex nature of SES across various outcomes in children (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002).

Moderation of Sleep and Academic Performance by Concurrent SES

To replicate and extend prior literature, the third aim of this study considered concurrent SES as a moderator of the relation between sleep and academics. There were no significant interactions between concurrent SES with sleep duration or sleep midpoint to predict academic performance, differing from research suggesting that increased sleep duration was associated with better academic performance for children from high SES homes (Buckhalt et al., 2007) and higher math performance for children from households with low parental education two years later (Buckhalt et al., 2009). In a different sample, greater parent-reported sleep duration was related to lower academic stress, but only for children from low SES backgrounds (Buzek et al., 2019). We did find that more parent-reported sleep problems were related to poorer Picture Vocabulary performance and lower parent-reported academic achievement for high SES youth. In a sample of children and adolescents from the southeastern United States, higher child-reported sleep/wake problems predicted lower verbal ability for children from families with high father education (Buckhalt et al., 2009). However, associations between adolescent-reported sleep-wake problems and cognitive performance did not vary by SES (El-Sheikh et al., 2019). It is likely that differences in measurement and demographic characteristics contributed to varying findings across studies. The aforementioned studies indexed SES in a variety of ways, including family income divided by number of members in the household (El-Sheikh et al., 2019), a composite of monthly income (divided by number of individuals in the household), level of education, and occupational status (Buzek et al., 2019), and Hollingshead (1975) indices (Buckhalt et al., 2007; 2009). Differing measures of SES have advantages and disadvantages, given the complex and multifaceted nature of SES (Shavers, 2007). As suggested by Shavers (2007), our study considered both individual- and area-level indices, including an income-to-needs ratio that accounted for yearly income, household size, and federal poverty threshold, as well as primary and secondary caregiver education level. Together, our study demonstrates the importance of examining research questions across different samples to better understand how findings generalize to children from various backgrounds.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study included the multimethod assessment of sleep and academic outcomes as well as the sample’s excellent compliance with study procedures. Additionally, our study was well-powered, and the socioeconomic diversity in the sample made it possible to test the aims. However, there were also several limitations. First, it is possible that sleep behaviors might differ between twin and singleton children. For example, twins could be more likely to share a room compared to single-born children, potentially leading to sleep problems due to increased night-wakings or longer sleep latencies. However, several studies have suggested that twins are representative of singleton children on sleep and academic performance (Borkenau et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2011) and descriptive statistics in our study are comparable to other research that consider children’s sleep and academic performance (e.g., Berger et al., 2019; Portilla et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2013). Additionally, we only considered the role of family SES, although research has also shown the effects of neighborhood and school SES on academic outcomes (Sirin, 2005). Finally, it is possible that shared method variance could partially explain significant associations between the parent-reported measures of sleep problems and academic achievement.

Conclusion

Acknowledging these limitations, our study highlights the complex interplay between sleep, academic outcomes, and the family socioeconomic context. Future directions include the use of longitudinal person-centered approaches (e.g., Hoyniak et al., 2019) to examine potential mediators (e.g., sleep, diet) or moderators (e.g., temperament) of associations between sleep and academic performance. Additionally, it will be especially important to re-examine these associations as our sample enters adolescence, given the significant shifts in sleep behaviors as well as increased demand on academic performance (Galván, 2020; Yan et al., 2018). Finally, future work should examine the specific mechanisms by which early or concurrent socioeconomic contexts provide differential associations between sleep and academic performance. Understanding the qualities of these contexts that render youth more vulnerable to poor sleep can help identify targets of intervention that aid in children’s academic success.

Highlights.

We tested associations whether early and concurrent SES moderated associations between objective and parent-reported sleep with academic performance in middle childhood.

There were no main effects of sleep on academic performance.

There was some evidence of moderation, however, most relations did not vary by early and concurrent SES.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by seed grants from the Institute for Mental Health Research, the Challenged Child Project, and the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University, as well as grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD079520 and R01HD086085). Special thanks to the staff and students for their dedication to the Arizona Twin Project, and the participating families who generously shared their experiences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure: There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

This study is not linked to any clinical trials.

Non-financial disclosure: none.

References

- Adelantado‐Renau M, Beltran‐Valls MR, Migueles JH, Artero EG, Legaz‐Arrese A, Capdevila‐Seder A, & Moliner‐Urdiales D (2019). Associations between objectively measured and self‐reported sleep with academic and cognitive performance in adolescents: DADOS study. Journal of Sleep Research, 28, e12811–e12819. 10.1111/jsr.12811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Storfer-Isser A, Taylor HG, Rosen CL, & Redline S (2009). Associations of executive function with sleepiness and sleep duration in adolescents. Pediatrics, 123, e701–e707. 10.1542/peds.2008-1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbabi T, Vollmer C, Dörfler T, & Randler C (2015). The influence of chronotype and intelligence on academic achievement in primary school is mediated by conscientiousness, midpoint of sleep and motivation. Chronobiology International, 32, 349–357. 10.3109/07420528.2014.980508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, & Goldstein LH (2003). Manual for the MacArthur health and behavior questionnaire (HBQ 1.0). MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development, University of Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Astill R, Van der Heijden K, Van IJzendoorn M, & van Someren E (2012). Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: a century of research meta-analyzed. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 1109–1138. 10.1037/a0028204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Barnes J, Boutwell B, & Boutwell B (2013). A demonstration of the generalizability of twin-based research on antisocial behavior. Behavior Genetics, 43, 120–131. 10.1007/s10519-012-9580-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DW (2011). Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics, 58, 649–665. 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner A, Boyle A, & Sadler S (2016). Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: The roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1053–1064. 10.1007/s10964-016-0431-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RH, Diaz A, Valiente C, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Doane LD, Thompson MS, Hernández MM, Johns SK, & Southworth J (2019). The association between home chaos and academic achievement: the moderating role of sleep. Journal of Family Psychology, 33, 975–981. 10.1037/fam0000535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Cimon‐Paquet C, Tétreault É, Carrier J, & Matte‐Gagné C (2020). Prospective relations between sleep in preschool years and academic achievement at school entry. Journal of Sleep Research, e13183. 10.1111/jsr.13183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicer A, Capraro MM, & Capraro R (2013). The effects of parent’s SES and education level on students’ mathematics achievement: Examining the mediation effects of parental expectations and parental communication. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 3, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Borkenau P, Riemann R, Angleitner A, & Spinath F (2002). Similarity of childhood experiences and personality resemblance in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: a test of the equal environments assumption. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 261–269. 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00150-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Born J & Wilhelm I (2012). System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychological Research, 76, 192–203. 10.1007/s00426-011-0335-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, & Corwyn RF (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehmer Y, Li S, Müller V, Oertzen T, & Lindenberger U (2007). Memory plasticity across the life span: uncovering children’s latent potential. Developmental Psychology, 43, 465–478. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein RS, Doane LD, & Lemery-Chalfant K (2019). Early life socioeconomic status moderates associations between objective sleep and weight-related indicators in middle childhood. Sleep health, 5, 470–478. 10.1016/j.sleh.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bub KL, Buckhalt JA, & El-Sheikh M (2011). Children’s sleep and cognitive performance: a cross-domain analysis of change over time. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1504–1514. 10.1037/a0025535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt JA (2011). Insufficient sleep and the socioeconomic status achievement gap. Child Development Perspectives, 5, 59–65. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00151.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt J, El-Sheikh M, & Keller P (2007). Children’s sleep and cognitive functioning: race and socioeconomic status as moderators of effects. Child Development, 78, 213–231. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt J, El-Sheikh M, Keller P, & Kelly R (2009). Concurrent and longitudinal relations between children’s sleep and cognitive functioning: the moderating role of parent education. Child Development, 80, 875–892. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley T, & Schatzberg A (2005). On the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 90, 3106–3114. 10.1210/jc.2004-1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzek T, Poulain T, Vogel M, Engel C, Bussler S, Körner A, Hiemisch A, & Kiess W (2019). Relations between sleep duration with overweight and academic stress—just a matter of the socioeconomic status? Sleep Health, 5, 208–215. 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso TDSG, Pompéia S, & Miranda MC (2018). Cognitive and behavioral effects of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: a systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine, 46, 46–55. 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Pokras O & Baquet C (2002). What is a “health disparity”? Public Health Reports, 117, 426–434. 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50182-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, March 17). About child & teen BMI. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

- Chaput J-P, Dutil C, & Sampasa-Kanyinga H (2018). Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number and how does age impact this? Nature and Science of Sleep, 10, 421–430. 10.2147/NSS.S163071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, & Miller GE (2012). “Shift-and-persist” strategies: Why low socioeconomic status isn’t always bad for health. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 135–158. 10.1177/1745691612436694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2002). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SJ, Wolfson AR, Tarokh L, & Carskadon MA (2018). An update on adolescent sleep: new evidence informing the perfect storm model. Journal of Adolescence, 67, 55–65. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald J, Meijer A, Oort F, Kerkhof G, & Bögels S (2010). The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14, 179–189. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald-Kaufmann J., Oort F, & Meijer A (2013). The effects of sleep extension on sleep and cognitive performance in adolescents with chronic sleep reduction: An experimental study. Sleep Medicine, 14, 510–517. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doane LD, Breitenstein RS, Beekman C, Clifford S, Smith TJ, & Lemery-Chalfant K (2019). Early life socioeconomic disparities in children’s sleep: The mediating role of the current ome environment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 56–70. 10.1007/s10964-018-0917-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Philbrook L, Kelly R, Hinnant J, & Buckhalt J (2019). What does a good night’s sleep mean? Nonlinear relations between sleep and children’s cognitive functioning and mental health. Sleep, 42, 1–12. 10.1093/sleep/zsz078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Shimizu M, Philbrook LE, Erath SA, & Buckhalt JA (2020). Sleep and development in adolescence in the context of socioeconomic disadvantage. Journal of Adolescence, 83, 1–11. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59, 77–92. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Arruda EH, Krull JL, & Gonzales NA (2018). Adolescent sleep duration, variability, and peak levels of achievement and mental health. Child Development, 89, e18–e28. 10.1111/cdev.12729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván A (2020). The need for sleep in the adolescent brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24, 79–89. 10.1016/j.tics.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith H, Lemery K, Buss K, & Campos J (1999). Genetic analyses of focal aspects of infant temperament. Developmental Psychology, 35, 972–985. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.4.972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber R, Somerville G, Bergmame L, Fontil L, & Paquin S (2016). School-based sleep education program improves sleep and academic performance of school-age children. Sleep Medicine, 21, 93–100. 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L, Berger LM, LeBourgeois MK, & Brooks-Gunn J (2009). Social and demographic predictors of preschoolers’ bedtime routines. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30, 394–402. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181ba0e64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four factor index of social status.

- Hoyniak CP, Bates JE, Staples AD, Rudasill KM, Molfese DL, & Molfese VJ (2019). Child sleep and socioeconomic context in the development of cognitive abilities in early childhood. Child Development, 90, 1718–1737. 10.1111/cdev.13042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S, & Hale L (2017). Sleep duration and child well-being: a nonlinear association. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46, 258–268. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1204920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrin D, McGrath J, & Quon E (2014). Objective and subjective socioeconomic gradients exist for sleep in children and adolescents. Health Psychology, 33, 301–305. 10.1037/a0032924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomeichuk SN, Randler C, Shabalina I, Fradkova L, & Borisenkov M (2016). The influence of chronotype on the academic achievement of children and adolescents–evidence from Russian Karelia. Biological Rhythm Research, 47, 873–883. 10.1080/09291016.2016.1207352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, & Power C (2003). Life course epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 778–783. 10.1136/jech.57.10.778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery-Chalfant K, Clifford S, McDonald K, O’Brien TC, & Valiente C (2013). Arizona twin project: A focus on early resilience. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16, 404–411. 10.1017/thg.2012.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery-Chalfant K, Oro V, Rea-Sandin G, Miadich S, Lecarie E, Clifford S, Doane LD, & Davis MC (2019). Arizona Twin Project: Specificity in risk and resilience for developmental psychopathology and health. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 22, 681–685. 10.1017/thg.2019.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Somerville G, Boursier J, Santisteban J, & Gruber R (2020). Sleep duration is associated with academic achievement of adolescent girls in mathematics. Nature and Science of Sleep, 12, 173–182. 10.2147/NSS.S237267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, & Latendresse S (2005). Children of the affluent: challenges to well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 49–53. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00333.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather N, & Jaffe L (2016). Woodcock-Johnson IV: Reports, Recommendations, and Strategies. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B, & Gianaros P (2010). Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186, 190–222. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Sedmak R, Boyle JT, Butler R, & Williamson AA (2016). Sleep Well!: A pilot study of an education campaign to improve sleep of socioeconomically disadvantaged children. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12, 1593–1599. 10.5664/jcsm.6338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, & Kaplan D (1985). A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non‐normal Likert variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38, 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus user’s guide, 7th Edn Los Angeles. CA: Muthén & Muthén, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon GM, Thompson JM, Han DY, Becroft DM, Clark PM, Robinson E, Waldie KE, Wild CJ, Black PN, & Mitchell EA (2008). Short sleep duration in middle childhood: risk factors and consequences. Sleep, 31, 71–78. 10.1093/sleep/31.1.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Spirito A, & McGuinn M (2000). The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep, 23, 1043–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbrook LE, Hinnant JB, Elmore-Staton L, Buckhalt JA, & El-Sheikh M (2017). Sleep and cognitive functioning in childhood: Ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sex as moderators. Developmental Psychology, 53, 1276–1285. 10.1037/dev0000319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbrook LE, Shimizu M, Buckhalt JA, & El-Sheikh M (2018). Sleepiness as a pathway linking race and socioeconomic status with academic and cognitive outcomes in middle childhood. Sleep Health, 4, 405–412. 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plihal W, & Born J (1997). Effects of early and late nocturnal sleep on declarative and procedural memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 9, 534–547. 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portilla XA, Ballard PJ, Adler NE, Boyce WT, & Obradović J (2014). An integrative view of school functioning: transactions between self-regulation, school engagement, and teacher-child relationship quality. Child Development, 85, 1915–1931. 10.1111/cdev.12259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posthuma D, De Geus EJ, Bleichrodt N, & Boomsma DI (2000). Twin–singleton differences in intelligence?. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 3, 83–87. 10.1375/136905200320565535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, Curran P, & Bauer D (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quach J, Hiscock H, Canterford L, & Wake M (2009). Outcomes of child sleep problems over the school-transition period: Australian population longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 123, 1287–1292. 10.1542/peds.2008-1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey AE, Guignard-Perret A, Imler-Weber F, Garcia-Larrea L, & Mazza S (2020). Improving sleep, cognitive functioning and academic performance with sleep education at school in children. Learning and Instruction, 65, 101270. 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A (2007). Consequences of sleep loss or sleep disruption in children. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 2, 513–520. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Sharkey M, & Carskadon MA (1994). Activity-based sleep-wake identification: an empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep, 17, 201–207. 10.1093/sleep/17.3.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrank FA, McGrew KS, Mather N, & Woodcock RW (2014). Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Achievement. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Seegers V, Touchette E, Dionne G, Petit D, Seguin J, Montplaisir J, Vitaro F, Falissard B, Boivin M, & Tremblay R (2016). Short persistent sleep duration is associated with poor receptive vocabulary performance in middle childhood. Journal of Sleep Research, 25, 325–332. 10.1111/jsr.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL (2007). Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99, 1013–1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, & Wood DL (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75, 417–453. 10.3102/00346543075003417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siva Kumar CT, Rajan M, Pasupathy U, Chidambaram S, & Baskar N (2021). Effect of sleep habits on academic performance in schoolchildren age 6 to 12 years: a cross-sectional observation study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, jcsm-9520. 10.5664/jcsm.9520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa ICD, Louzada FM, & Azevedo CVMD (2009). Sleep-wake cycle irregularity and daytime sleepiness in adolescents on schooldays and on vacation days. Sleep Science, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Stormark KM, Fosse HE, Pallesen S, & Hysing M (2019). The association between sleep problems and academic performance in primary school-aged children: Findings from a Norwegian longitudinal population-based study. PloS One, 14, e0224139–e0224139. 10.1371/journal.pone.0224139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull JC (2013). Family socioeconomic status, parent expectations, and a child’s achievement. Research in Education, 90, 53–67. 10.7227/RIE.90.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland G, & McNaughton B (2000). Memory trace reactivation in hippocampal and neocortical neuronal ensembles. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 10, 180–186. 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00079-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti L, Natale V, & Randler C (2015). Association between circadian preference and academic achievement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chronobiology International, 32, 792–801. 10.3109/07420528.2015.1049271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM, & Wolfson AR (2017). The intersection between sleep science and policy: introduction to the special issue on school start times. Sleep Health, 3, 419–422. 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal V (2015). Test Review: Schrank FA, Mather N, & McGrew KS (2014). Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Achievement. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33, 391–398. 10.1177/0734282915569447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Xu G, Liu Z, Lu N, Ma R, & Zhang E (2012). Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances among Chinese school-aged children: Prevalence and associated factors. Sleep Medicine, 14, 45–52. 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson AA, Mindell JA, Hiscock H, & Quach J (2020). Longitudinal sleep problem trajectories are associated with multiple impairments in child well‐being. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61, 1092–1103. 10.1111/jcpp.13303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Lin R, Su Y, & Liu M (2018). The relationship between adolescent academic stress and sleep quality: A multiple mediation model. Social Behavior and Personality, 46, 63–77. 10.2224/sbp.6530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Hsu H, Kwok O, Benz M, & Bowman-Perrott L (2011). The impact of basic-level parent engagements on student achievement: patterns associated with race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES). Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 22, 28–39. 10.1177/1044207310394447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]