Abstract

Introduction: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is frequently used for the elderly population. Older patients are more fragile than younger patients because of multiple age-related chronic diseases and the common use of polypharmacy. There is no adequate data in the existing literature regarding the application of upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy in the elderly population. Therefore, in this article, we evaluated esophagogastroduodenoscopy procedures that were performed on patients aged 75 years or older in the secondary care hospital.

Methods: We performed a retrospective observational study of patients aged 75 years or older who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy between January 2016 and January 2021 at the Istanbul Sultanbeyli State Hospital Endoscopy Unit. Indications of endoscopy, ages, genders, endoscopic diagnoses, polyp/tumor/biopsy localizations, histopathological examination of biopsies, and complications of esophagogastroduodenoscopy were analyzed.

Results: A total of 202 patients were analyzed. The most common indication was dyspepsia (25%), followed by gastrointestinal bleeding, reflux, anemia, and screening/surveillance. For patients aged 75-79 years and patients aged ≥80 years, endoscopic diagnoses of esophageal and gastric malignancies were observed as 6.4% and 18%, respectively. Very relevant findings of endoscopy (esophageal and gastric malignancies; gastric and duodenal ulcers) were detected in 39 (19.3%) of all included patients. No complications due to endoscopic procedures were observed, but complications due to sedation (hypotension and hypoxemia) were observed in 5.0%.

Conclusion: After pre-procedural evaluation, we must be careful while doing endoscopic procedures in the elderly because of multiple age-related chronic diseases and the common use of polypharmacy. This present study showed that esophagogastroduodenoscopy is a safe procedure with a high diagnostic yield in patients aged 75 years and older.

Keywords: octogenarians, aged, gastrointestinal endoscopy, digestive system, gastroscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Introduction

Although diseases and injuries occur regularly, the world population continues to live longer. The average life expectancy (73.3 years) and healthy life expectancy (63.7 years) in 2019 showed marked increases since 2000. With that increasing age, the incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases in the elderly increased as well [1].

GI endoscopy is one of the most important tools for diagnosis, surveillance, and treatment of GI diseases. Endoscopic procedures have been applied more and more frequently in the elderly. The published data shows that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is high-yielding in elderly patients, though we must take care to apply the procedure safely because of this age group’s frailty. Symptoms of anemia, dysphagia, epigastric pain, and GI bleeding, especially in male patients, should be taken into consideration for EGD because of increased malignancy or peptic ulcer disease risk [2,3].

We need more information about the application of upper GI system endoscopy in the elderly population. Therefore, in this article, we evaluated EGD procedures that were performed on patients aged 75 years or older in the Istanbul Sultanbeyli State Hospital. The aim of this study was to analyze the indications, endoscopic diagnosis, histopathological findings, and complications of upper GI endoscopy.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective observational study of patients who underwent EGD from January 2016 to January 2021 at the Istanbul Sultanbeyli State Hospital Endoscopy Unit. This study was approved by the Marmara University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Number: 09.2021-724) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05012527).

We used patients’ endoscopy and hospital records for data acquisition. Patients with missing data and duplicate records were excluded from the study. Patients aged 75 years or older who underwent EGD were included in the analysis. The following parameters were analyzed: age, gender, endoscopy indications, endoscopic diagnosis, polyp/tumor/biopsy localization, histopathological examination of biopsies, and complications. For further analysis, patients were stratified according to age into two groups: 75-79 and ≥80. The endoscopy indications were classified by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines [4]. Morphological features and grade of endoscopic gastric biopsies were reported according to the Sydney System (Helicobacter pylori/atrophy/intestinal metaplasia/chronic inflammation/activity) [5]. Malignancy, esophagitis, esophageal varices, gastritis, gastric erosion, gastric ulcer, gastric polyp, duodenitis, duodenal ulcer, and duodenal polyp are defined as relevant endoscopic findings. Esophageal malignancy, gastric ulcer, gastric malignancy, and duodenal ulcer are defined as very relevant endoscopic findings [6]. We calculated the overall diagnostic yield according to these parameters.

All endoscopies were performed using standard video-endoscopes (Fujinon EG-530WR) by seven general surgeons who had at least five years of experience in endoscopy. The patients fasted for at least 8 hours before the procedure. Almost all EGD procedures were performed while the patients were under sedation. Conscious sedation was achieved with propofol 1% 10 mg/ml by an anesthetic technician under the supervision of an anesthesiologist. Continuous monitoring was provided by recording oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and pulse rate.

The primary outcome of this study was to determine indications, endoscopic diagnosis, histopathological findings, and complications of upper GI endoscopy.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 24 for Mac, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. For quantitative variables, a t-test, a Mann-Whitney U-test, a Kruskal-Wallis test, and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) were applied. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

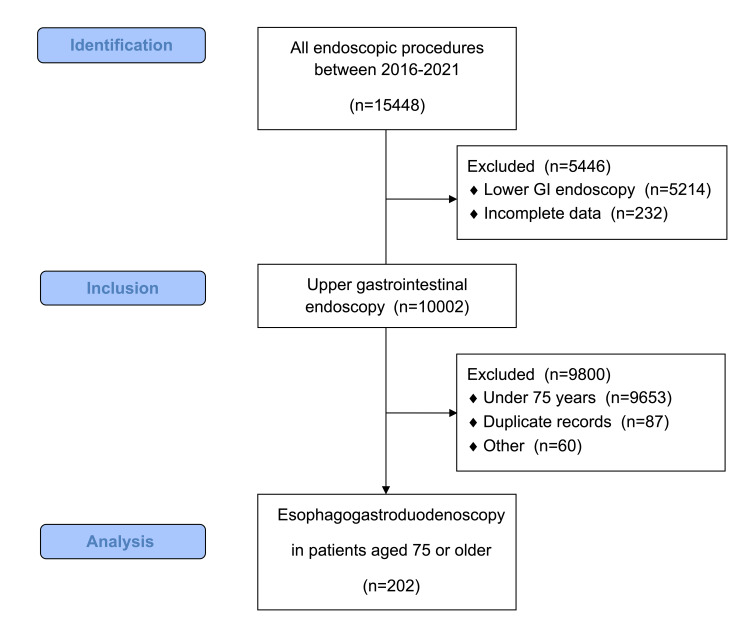

A total of 202 patients were evaluated retrospectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient selection.

GI: gastrointestinal

Seventy-one of the patients were male (35%). The mean age was found to be 79 years. When the endoscopy indications were examined, the most common indication was dyspepsia (25%), followed by GI bleeding, reflux, anemia, and screening/surveillance.

Endoscopic findings were examined, and antral gastritis and pangastritis were observed frequently. The incidence of malignancy for all patients ranged from 2% for the esophagus and up to 9% for the stomach. The prevalence of esophageal and gastric malignancies in patients over 80 years of age was observed as 3.9% and 14.3%, respectively. The pathological findings showed that chronic active gastritis was found in 42.6% of the patients. The final diagnoses of some cases that were reported by endoscopists as malignancy were found to be premalignant lesions in pathology. GI system malignancy detected pathologically was 9.4% in the entire cohort and 15% in the patients over 80 years of age. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.24) (Table 1).

Table 1. Patients’ demographics, indications, and endoscopic and pathological findings .

GI: gastrointestinal; VRF: very relevant findings (esophageal malignancy, gastric ulcer, gastric malignancy, and duodenal ulcer)

| Parameters | Total n: 202 (%) | Age group 75-79, n | Age group ≥80, n | P-value |

| Age (years, mean-range) | 79 | |||

| Sex | 0.98 | |||

| Female | 131 | 81 | 50 | |

| Male | 71 | 44 | 27 | |

| Endoscopy indications | 0.48 | |||

| Dyspepsia | 52 (25.7%) | 34 | 18 | |

| Abnormal imaging | 10 (5.0%) | 8 | 2 | |

| Reflux | 21 (10.4%) | 12 | 9 | |

| Dysphagia | 11 (5.4%) | 5 | 6 | |

| Upper GI bleeding | 25 (12.4%) | 13 | 12 | |

| Anemia | 21 (10.4%) | 11 | 10 | |

| Vomiting | 10 (5.0%) | 6 | 4 | |

| Screening/surveillance | 21 (10.4%) | 13 | 8 | |

| Weight loss | 13 (6.4%) | 8 | 5 | |

| Abdominal pain | 18 (8.9%) | 15 | 3 | |

| Endoscopic diagnosis | 0.07 | |||

| Esophagitis | 15 (7.4%) | 11 | 4 | |

| Bile reflux gastritis | 4 (2.0%) | 1 | 3 | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 4 (2.0%) | 2 | 2 | |

| Duodenal polyp | 2 (1.0%) | 0 | 2 | |

| Normal finding | 19 (9.4%) | 16 | 3 | |

| Gastric ulcer | 13 (6.4%) | 7 | 6 | |

| Duodenitis | 9 (4.5%) | 6 | 3 | |

| Gastric polyp | 10 (5.0%) | 7 | 3 | |

| Other | 5 (2.5%) | 4 | 1 | |

| Esophageal malignancy | 4 (2.0%) | 1 | 3 | |

| Esophageal varices | 3 (1.5%) | 1 | 2 | |

| Hiatal hernia | 15 (7.4%) | 8 | 7 | |

| Antral gastritis | 27 (13.4%) | 21 | 6 | |

| Pangastritis | 24 (11.9%) | 17 | 7 | |

| Gastric erosion | 16 (7.9%) | 9 | 7 | |

| Gastric malignancy | 18 (8.9%) | 7 | 11 | |

| Findings secondary to operation | 14 (6.9%) | 7 | 7 | |

| Very Relevant Findings (VRF) | 39 (19.3%) | 17 (13.6%) | 22 (28%) | 0.008 |

| Pathological Finding | 0.24 | |||

| Chronic active gastritis | 86 (42.6%) | 54 | 32 | |

| Low-grade dysplasia | 3 (1.5%) | 2 | 1 | |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 2 (1.0%) | 0 | 2 | |

| Inflammatory fibroid polyp | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | |

| Chronic gastritis | 65 (32.2%) | 45 | 20 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 17 (8.4%) | 7 | 10 | |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 6 (3.0%) | 4 | 2 | |

| Ulceration | 4 (2.0%) | 2 | 2 | |

| Duodenitis | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | |

| Chronic esophagitis | 2 (1.0%) | 0 | 2 | |

| Erosive gastritis | 3 (1.5%) | 2 | 1 | |

There was no significant difference between age groups in terms of pathological results (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of pathologic outcomes by age groups.

| Parameters | Total n: 202 (%) | Age group 75-79, n | Age group ≥80, n | P-value |

| Atrophy | 0.9 | |||

| None | 147 (91%) | 98 | 49 | |

| Mild | 10 (6%) | 7 | 3 | |

| Moderate | 5 (3%) | 3 | 2 | |

| Helicobacter pylori | 0.45 | |||

| None | 36 (22.4%) | 27 | 9 | |

| Mild | 93 (57.8%) | 60 | 33 | |

| Moderate | 32 (19.9%) | 20 | 12 | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.58 | |||

| None | 127 (78.4%) | 88 | 39 | |

| Mild | 18 (11%) | 10 | 8 | |

| Moderate | 15 (9.3%) | 9 | 6 | |

| Severe | 2 (1.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Chronic inflammation | 0.191 | |||

| Mild | 110 (68%) | 77 | 33 | |

| Moderate | 52 (32%) | 31 | 21 | |

| Activity | 0.38 | |||

| None | 75 (46.3%) | 52 | 23 | |

| Mild | 70 (43.2%) | 47 | 23 | |

| Moderate | 16 (9.9%) | 9 | 7 | |

| Severe | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 1 | |

A positive correlation was found between atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, while a negative correlation was found with the density of H. pylori (p = 0.00 and p = 0.04, respectively). The density of H. pylori was significantly correlated with the severity of chronic inflammation and activity (p = 0.00 and p = 0.00, respectively). On the other hand, there was a significant positive correlation between intestinal metaplasia and chronic inflammation (p = 0.005) (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations between pathologic outcomes.

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (Two-tailed) **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (Two-tailed)

| Atrophy | Helicobacter pylori | Intestinal metaplasia | Chronic inflammation | Activity | |

| Atrophy | 1.000 | −0.157* | 0.616** | 0.054 | 0.151 |

| . | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.495 | 0.055 | |

| Helicobacter pylori | −0.157* | 1.000 | −0.061 | 0.453** | 0.431** |

| 0.046 | . | 0.439 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.616** | −0.061 | 1.000 | 0.220** | 0.132 |

| 0.000 | 0.439 | . | 0.005 | 0.094 | |

| Chronic inflammation | 0.054 | 0.453** | 0.220** | 1.000 | 0.498** |

| 0.495 | 0.000 | 0.005 | . | 0.000 | |

| Activity | 0.151 | 0.431** | 0.132 | 0.498** | 1.000 |

| 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.000 | . |

Among the patients aged 75-79 years and ≥80 years, 17 (13.6%) and 22 (28%) very relevant findings (VRFs) at endoscopy were detected, respectively. These VRFs were significantly different between the two age groups (p = 0.0088). Thirty-nine (19.3%) VRFs at endoscopy were cumulatively detected (Table 1). The complication rate was 5%. Hypotension (1%) and hypoxemia (4%) occurred and were treated successfully. Bleeding, perforation, and procedure-related deaths were not seen.

Discussion

EGD is frequently used in the increasing elderly population. Older patients are more fragile than younger ones because of multiple age-related chronic diseases and the common use of polypharmacy [7,8]. For these reasons, we must be careful doing endoscopic procedures in the elderly. Previously published studies showed that EGD is a safe procedure in elderly patients if good pre-procedural evaluations, such as a cardiorespiratory examination and an airway assessment, are performed [9-11]. Dyspepsia is a common health problem globally and is seen in approximately 20% of the population. Guidelines suggest that patients ≥60 years of age presenting with dyspepsia should be investigated with upper GI endoscopy to exclude GI neoplasia [12,13]. In this study, the most common EGD indication was dyspepsia, followed by GI bleeding, reflux, anemia, and screening/surveillance. This finding is compatible with the existing literature [6,9,14,15]. In the patients’ endoscopic examinations, gastritis was commonly detected and was compatible with chronic active gastritis, which was detected in 42.6% of the patients in pathology reports.

The prevalence of malignancies increased with aging in our results. Among the patients aged 75-79 years and ≥80 years, endoscopic diagnoses of esophageal and gastric malignancies were observed as 6.4% and 18%, respectively. This result is compatible with other studies [2,6,9,16]. Our cumulative diagnostic yield was 19.3% according to VRF, and it increased with age. Our results and literature showed that the yield of EGD is high in elderly patients. We should not give up due to advanced age when making decisions regarding EGD in elderly patients [2,3,6,9,16].

H. pylori infection causes active chronic gastritis and plays an important role in the development of atrophic gastritis, as described in Correa’s hypothesis, and gastric atrophy has been recognized as a precancerous condition. Patients with histological intestinal metaplasia and severe atrophy have an increased risk of developing gastric cancer. Significant improvements in gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia after the eradication of H. pylori may reduce the risk of gastric cancer [17,18]. However, in Grgov et al.’s study, a negative correlation was observed between the frequency of atrophy and H. pylori, which is consistent with our results [19]. This conclusion may have been reached because H. pylori causes atrophy but does not colonize atrophic areas.

Our complication rate was 5%, and we did not detect major complications. In our hospital, we don’t apply emergency endoscopic intervention and advanced therapeutic procedures. So, this may relate to our low complication rate. Our study and the literature showed that EGD is a safe procedure in elderly patients. We performed an assessment of each patient’s cardiopulmonary status and comorbid conditions and modified the use of sedation or avoided sedation to reduce complications during endoscopic procedures. The diagnostic use of EGD in elderly patients is not associated with high complication rates [3,9,16,20,21].

Our study has certain limitations. It is a retrospective, single-center, and low‐volume study. Our center is a secondary care hospital, and we don’t apply advanced endoscopic interventions. We didn’t know our patients’ medications, previous H. pylori eradication histories, or comorbidity statuses. These conditions may affect our results and the complication rate of procedures.

Conclusions

The application of EGD over the age of 75 is increasing with the expansion in the older population. After pre-procedural evaluation, we must be careful while performing endoscopic procedures in the elderly because of multiple age-related chronic diseases and the common use of polypharmacy. This present study showed that EGD is a safe procedure with a high diagnostic yield in patients aged 75 years and older.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Marmara University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee issued approval 09.2021-724. This study was approved by the Marmara University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Number: 09.2021-724) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05012527).

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. World health statistics 2021: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endoscopy in the elderly. Travis AC, Pievsky D, Saltzman JR. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1495–1501. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gastrointestinal endoscopy in the elderly: current issues. Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Malfertheiner P, Schuckardt W. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appropriate use of GI endoscopy. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Early DS, Ben-Menachem T, et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1127–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Sydney System for classification of gastritis 20 years ago. Sipponen P, Price AB. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upper GI endoscopy in elderly patients: predictive factors of relevant endoscopic findings. Buri L, Zullo A, Hassan C, et al. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aging and multimorbidity: new tasks, priorities, and frontiers for integrated gerontological and clinical research. Fabbri E, Zoli M, Gonzalez-Freire M, Salive ME, Studenski SA, Ferrucci L. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polypharmacy in older patients with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional analysis of factors associated with excessive polypharmacy. Rieckert A, Trampisch US, Klaaßen-Mielke R, et al. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0795-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The indications, utilization and safety of gastrointestinal endoscopy in an extremely elderly patient cohort. Clarke GA, Jacobson BC, Hammett RJ, Carr-Locke DL. Endoscopy. 2001;33:580–584. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endoscopy in the elderly: a review of the efficacy and safety of colonoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Jafri SM, Monkemuller K, Lukens FJ. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:161–166. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c64d64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Complications and outcomes of routine endoscopy in the very elderly. Miyanaga R, Hosoe N, Naganuma M, et al. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:0–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ACG and CAG Clinical Guideline: management of dyspepsia. Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, Enns RA, Howden CW, Vakil N. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988–1013. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, Moayyedi P. Gut. 2015;64:1049–1057. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rate and yield of repeat upper endoscopy in patients with dyspepsia. Ladabaum U, Dinh V. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2520–2525. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A nine-year audit of open-access upper gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: results and experience of a single centre. Keren D, Rainis T, Stermer E, Lavy A. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:83–88. doi: 10.1155/2011/379014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients aged 85 years or more. Results of a feasibility study in a district general hospital. Van Kouwen MC, Drenth JP, Verhoeven HM, Bos LP, Engels LG. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;37:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(03)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ten-year prospective follow-up study on the relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and progression of atrophic gastritis, particularly assessed by endoscopic findings. Sakaki N, Kozawa H, Egawa N, Tu Y, Sanaka M. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:198–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.16.s2.13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The correlation of endoscopic and histological diagnosis of gastric atrophy. Eshmuratov A, Nah JC, Kim N, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1364–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The relationship between the density of Helicobacter pylori colonisation and the degree of gastritis severity. Grgov S, Stefanovic M, Vuka K. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288144885_The_relationship_between_the_density_of_Helicobacter_pylori_colonisation_and_the_degree_of_gastritis_severity Arch Gastroenterohepatol. 2002;21:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Modifications in endoscopic practice for the elderly. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Early DS, Acosta RD, et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Age is not a discriminating factor for outcomes of therapeutic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Lee TC, Huang SP, Yang JY, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17708245/ Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1319–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]