Keywords: dopamine, reinforcement learning, songbird, subthalamic nucleus

Abstract

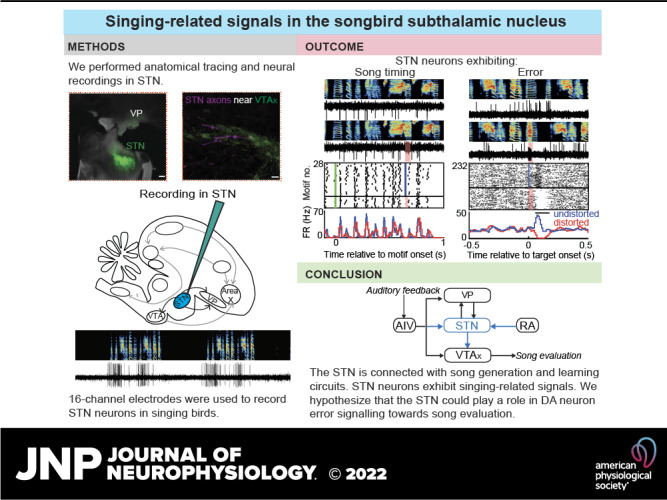

Skill learning requires motor output to be evaluated against internal performance benchmarks. In songbirds, ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopamine neurons (DA) signal performance errors important for learning, but it remains unclear which brain regions project to VTA and how these inputs may contribute to DA error signaling. Here, we find that the songbird subthalamic nucleus (STN) projects to VTA and that STN microstimulation can excite VTA neurons. We also discover that STN receives inputs from motor cortical, auditory cortical, and ventral pallidal brain regions previously implicated in song evaluation. In the first neural recordings from songbird STN, we discover that the activity of most STN neurons is associated with body movements and not singing, but a small fraction of neurons exhibits precise song timing and performance error signals. Our results place the STN in a pathway important for song learning, but not song production, and expand the territories of songbird brain potentially associated with song learning.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Songbird subthalamic (STN) neurons exhibit singing-related signals and are interconnected with the motor cortical nucleus, auditory pallium, ventral pallidum, and ventral tegmental area, areas important for song generation and learning.

INTRODUCTION

The songbird subthalamic (STN) is a glutamatergic nucleus in the vertebrate diencephalon. Activation of STN neurons activates basal ganglia (BG) outputs, which in turn suppress downstream motor centers to halt ongoing actions (1–6). The idea that the STN acts as a “brake” of movements is supported by its effectiveness as a therapeutic target for hypokinetic disorders such as Parkinson’s (7–9).

More recently the STN has additionally been implicated in reward processing and learning (10–12). The STN projects to midbrain dopamine neurons (13–15), STN stimulation activates DA neurons and increases striatal DA levels (16–19), STN neurons exhibit reward- and reward cue-related signals (10, 14, 20), and STN lesions impair reward-seeking behavior (20–22). These studies in mammals suggest that the STN could play a role in reinforcement learning (RL), which is known to rely on DA evaluation signals (23, 24).

The STN is evolutionarily conserved among vertebrates, and a comparative approach could help elucidate core functions. Songbirds provide a tractable model system because they learn to sing and have a specialized “song system” that includes a cortex-dopamine-BG pathway that evaluates song performance during singing (25–29). Two recent studies identified the STN in birds. In pigeons, unilateral STN lesions caused a wing hyperkinesis similar to the hemiballism observed in mammals (30), consistent with the brake hypothesis of STN function. In songbirds, STN was identified as being reciprocally connected with the ventral pallidum (VP) (31), but no interconnectivity with the song system, including the song-specialized BG nucleus Area X, led to the idea that the STN is not a singing-related structure in songbirds (28).

Although VP, like the STN, is outside the classic song system (28), recent studies showed that VP is part of a “critic” pathway that evaluates the quality of song performance online (32). First, VP lesions do not affect song production but do impair song learning. Second, optogenetic photoactivation of the VP-VTA projection can reinforce specific song syllables (33). Finally, VTA-projecting VP neurons exhibit responses to distorted auditory feedback (DAF) during singing. VTA DA neurons in turn send these error signals to Area X, where DA-modulated striatal plasticity occurs and drives learning (34–37). STN’s interconnectivity with VP led us to hypothesize that it could also play a role in song learning or evaluation.

Here, we combine neural tracing, functional mapping, and neural recordings in awake, singing birds to test if the STN exhibits connectivity and signaling consistent with a role in song learning. We find that singing-related structures, including auditory and vocal motor cortical areas previously implicated in song learning and production, project to STN, and that STN in turn projects to the part of the DA midbrain implicated in song learning. We also find that some STN neurons exhibit singing-related neural activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were 52 adult male zebra finches (at least 90 days post hatch, dph). Animal care and experiments were carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines and were approved by the Cornell Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgery and Histology

For all surgeries, birds were anaesthetized under isoflurane. All anatomical coordinates are expressed as anteroposterior (A) distance with respect to the midsagittal bifurcation of the sinus vein (lambda), mediolateral (L) distance with respect to the sinus vein, and dorsoventral (V) distance with respect to the pial surface. The head angle for all coordinates reported here are measured as the angle from the tip of the beak to the center of the ear bars relative to the horizontal plane. We first set out to replicate the previously reported VP-STN projection (30, 31) to obtain an anatomical reference for all other experiments. For this, we injected 100 nL of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing self-complementary adeno-associated virus (scAAV9-CBh-GFP, UNC vector core) into VP (4.9 A, 1.3 L, 3.8 V at 20° head angle) bilaterally. Based on the location of the cluster of VP-projecting neurons in the anterior diencephalon and its posteroanterior distance from the auditory thalamus (Ovoidalis) and dorsoventral distance from the injection site in VP, we computed the coordinates of STN for future experiments. For every retrograde tracer injection into this diencephalic region, presence of labeled cells in VP was used as the primary determinant to confirm that we indeed were injecting in the previously identified STN. This was especially important as the STN does not appear as a discrete nucleus unlike other well-studied regions of the song-circuit in zebra finches.

To identify areas projecting to both STN and VTA, two birds were doubly injected with 70 nL scAAV9-CBh-GFP bilaterally in STN (4.6 A, 0.6 L, 4.6/4.9V at 40° head angle) and 50 nL CTB647 bilaterally in VTA (2.4 A, 0.6 L, 6.3 V at 55° head angle), and brain areas were examined for colabeling.

In a set of two birds, ∼40 nL anterograde virus HSV-mCherry (MGH, Viral Core) was injected in STN along with CTB488 in Area X to test if STN axons localized with X-projecting VTA neurons. Birds were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde solution, and 100 µm sagittal slices were obtained for imaging. All imaging was acquired using Leica DM4000 B microscope except for imaging STN axons in VTA (Fig. 1E) that was obtained using Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

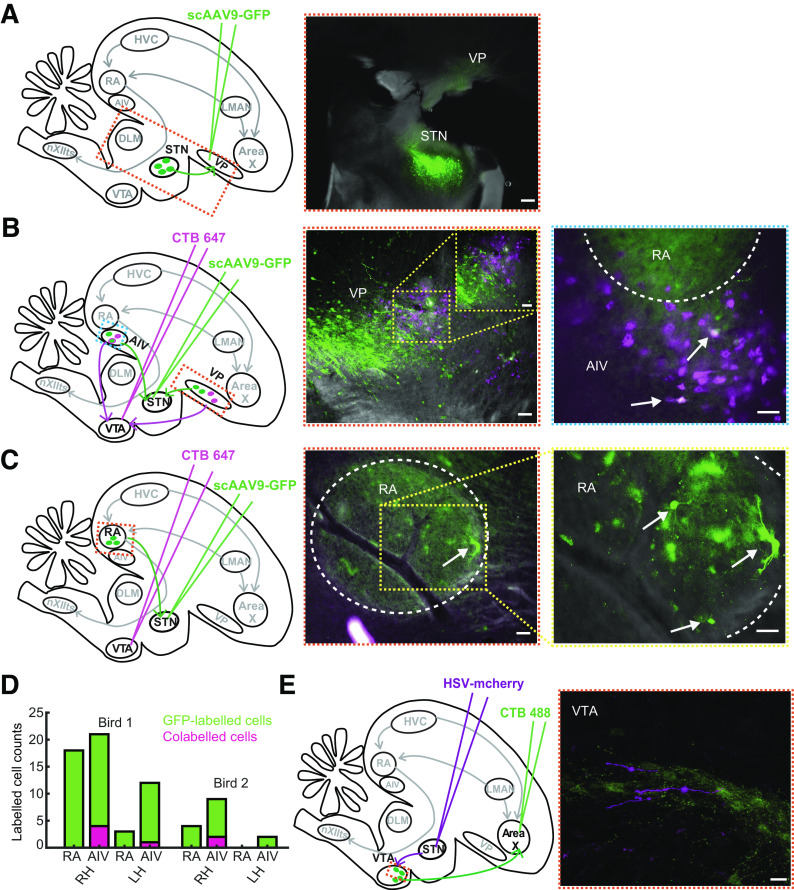

Figure 1.

STN receives projections from AIV and RA and projects to VTA neurons. A: injection of retrograde viral tracer scAAV9-GFP in VP resulted in labeled cells in STN. Scale bar: 250 μm. B: injection of scAAV9-GFP in STN and retrograde tracer, cholera toxin subunit B 647 in VTA were performed to test for collateral projections from VP and AIV to STN and VTA. Center: STN-projecting cells (green) were observed intermingled with VTA-projecting cells (magenta) in VP. A zoomed-in (×20 magnification) portion of the VP, where both VP-STN and VP-VTA cells were observed, is shown as inset. None of the cell bodies showed colabeling. Scale bar: 50 μm. Right: colabeled cells were observed in AIV (arrows), located just below the RA (ventral boundary bordered by white dashed lines), suggesting the presence of a population of AIV neurons sending projections to both STN and VTA. Scale bar: 50 μm. C: injection of scAAV9-GFP in STN also resulted in GFP-labeled cell bodies in RA (bounded by white dashed lines). The panel to the right shows a zoomed-in (×20 magnification) portion of the RA. Scale bar: 50 μm. D: manual counting of labeled cell bodies in RA and AIV were performed for each hemisphere (right hemisphere, RH and left hemisphere, LH) in the two birds doubly injected with retrograde viral tracer and CTB647. The height of each bar represents the total number of GFP-labeled cell bodies observed. The magenta shaded portion in each bar represents the number of these GFP-labeled cell bodies that were colabeled with CTB647. E: anterograde viral tracer HSV-mCherry was injected in STN along with retrograde CTB488 in Area X to assess if STN projected to X-projecting VTA neurons (VTAx). Image was obtained under confocal microscope, which showed labeled axons from STN adjacent to VTAx neurons. The mCherry-labeled axons were pseudo-colored for colorblindness. Scale bar: 20 μm. AIV, ventral anterior intermediate arcopallium; GFP, green fluorescent protein; RA, robust nucleus of the arcopallium; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VP, ventral pallidum; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Functional Mapping and Neural Analysis

For functional mapping experiments, birds (n = 8) were implanted with bipolar stimulating electrodes in Area X and STN. All recordings were performed in anaesthetized birds. VTA was identified with reference to the DLM-Ovoidalis boundary (38) and VTA neurons were recorded using a carbon fiber electrode (1 MΩ, Kation Scientific). Area X-projecting VTA neurons (VTAx) were confirmed by antidromic response and collision testing (200 μs pulses, 100–300 μA) using the Area X stimulating electrode. All VTA neurons recorded were tested for response to STN microstimulation. Small electrolytic lesions were made by passing ±30 μA of current for 60 s through the electrodes at the end of the experiment to confirm the locations of stimulation and recording.

The recorded VTA neurons (n = 13) were analyzed offline using custom software in MATLAB. Spike rasters aligned to stimulation times were computed to assess the response of VTA neurons to STN stimulation. Firing rate histograms were computed using 2-ms bins to account for the short latencies to the response of the VTA neurons to STN stimulation and smoothed with a 3-bin moving average. Each bin was tested for significant firing rate changes using a z-test (P < 0.05). Latency to response was defined as the first bin for which the next two consecutive bins were significantly different from previous activity (z-test, P < 0.05). Duration of response was computed from the total number of significant bins.

Awake-Behaving Electrophysiology

For awake-behaving electrophysiology, birds (n = 36) were implanted with 16-channel movable electrode bundles (Innovative Neurophysiology) over STN (4.1–4.7A, 0.6 L, 4.2 V at 40° head angle). Birds with 16-channel movable implants were placed in sound isolation chambers, maintained at 12-h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. They were allowed to recover for a day postop and then subjected to distorted auditory feedback (DAF) protocol for 2–3 days to habituate them and ensure sufficient motifs sung throughout the day before starting neural recording. Real-time analysis of singing was carried out using custom-written acquisition program in LabView. DAF was delivered through speakers on top of a specific syllable during the song, on 50% of randomly selected renditions (38). DAF was broadband noise of ∼25 ms duration, filtered at 1.5–8 kHz to match the spectral range of the finch song and delivered through dual speakers placed inside the recording chamber. At the end of the experiment, small electrolytic lesions were made to ascertain the location of the recording site. Out of the 36 implanted birds, neural data were obtained from seven birds where electrolytic lesions confirmed its location in the area identified as STN from anatomical studies. Most of the other implanted birds did not yield neural data and post hoc histology showed that the electrodes were either too anterior or too posterior, placing them near the optic chiasm or the fibers of passage, respectively. For these birds, we were unable to record any well-isolated single units and only observed sparse multiunit activity with low signal-to-noise ratio and were not used for further analysis.

Neural Recording and Analysis

Neural recordings were obtained using 16-channel INTAN headstages with the accompanying recording controller and INTAN acquisition software at a sampling rate of 20 kHz. The song and a copy of the DAF signal was recorded contiguously with the neural data through analog inputs on the INTAN recording controller to facilitate time alignment of all data. Spike sorting was performed offline using custom software in MATLAB (32, 39) that allowed visualization of the neural data time aligned with spectrograms of the bird song. Neural traces were broadband filtered between 0.4 and 8 kHz, and well-isolated spikes were identified manually based on the signal amplitude from baseline noise and shape. The firing rate histograms were computed using 10-ms bins and smoothed with a 3-bin moving average, except for analysis of the song-locked neurons that were computed with 4-ms bins (Fig. 3, A–C). To further quantify the firing of neurons locked to song timing, intermotif correlation coefficient (IMCC) was calculated as described previously (32, 40, 41). Neurons that exhibited a significant IMCC value were defined as exhibiting song-timing-related neural firing.

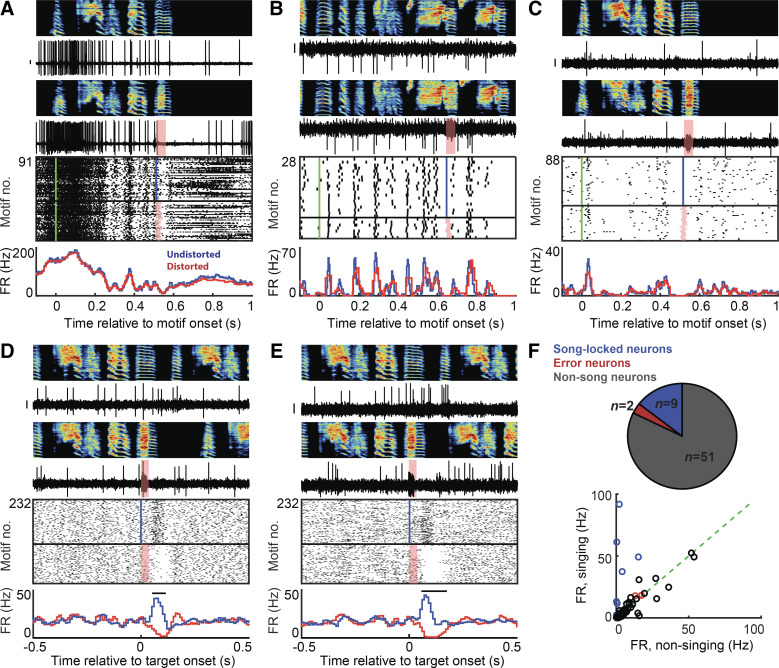

Figure 3.

A small population of STN neurons exhibit singing-related signals. A–E: examples of STN neurons in singing birds are shown with distorted and undistorted motifs on top along with the corresponding neural traces. For each neuron, rasters and firing rate histograms are depicted with distorted renditions in red and undistorted renditions in blue. Scale bar on all neural traces is 0.1 mV. A–C: example neurons exhibiting varying firing rates and precise time-locked firing during song. The motif-aligned rasters and firing rate histograms indicate no difference in neural response between distorted and undistorted trials. The green line in the rasters indicates motif onset time. D and E: two of the STN neurons recorded exhibited performance error signal, with decrease in firing rate on DAF-distorted trials and increase in firing rate during undistorted trials, indicated by the target-aligned rasters and firing rate histograms. F: overall, a small fraction of all neurons recorded exhibited song-locked firing rate modulation or error response. The song timing neurons exhibited increased firing rate during song compared with outside song (n = 8/9) (top right). The error neurons and the other neurons did not exhibit a significant difference in firing rate during vs. outside song. DAF, distorted auditory feedback; FR, firing rate; STN, subthalamic nucleus.

Movement analysis was performed on data from birds (n = 4) that were acquired using 16-channel INTAN headstages mounted with a 3-axis accelerometer. The net acceleration was computed as follows:

where, x, y, and z are the acceleration values from the 3-axis accelerometer signal. This net acceleration was used to compute thresholds for movement onsets and offsets using k-means clustering (38, 42). Movement onsets and offsets were detected based on threshold crossings of the smoothed (moving average with 25-ms windows) rectified net acceleration signal. Firing rate histograms were then computed using 10-ms bins and smoothed with a 3-bin moving average.

To test for significant movement-related firing rate changes, firing rate histograms were computed for ±300 ms of spiking activity around the movement onsets or offsets with 10-ms bin size and steps of 5 ms. Each bin was tested for significance using a z-test (P < 0.05). Latency of response was computed based on the first bin (w.r.t. movement onset/offset) for which four consecutive bins were significant. We further classified movement events as during singing and outside singing to assess if the neurons encoded movement differentially during the two behavioral states.

RESULTS

STN Receives Inputs from Auditory Pallium and Motor Cortical Area in Zebra Finches

Past work in pigeons identified a small area in the zebra finch diencephalon reciprocally connected to the VP, that when unilaterally lesioned produced contralateral hemiballism, providing both anatomical and functional signatures of STN (30, 31, 43, 44). We injected retrograde viral tracer (scAAV9-GFP) into VP and observed labeling in a small area in the anterior diencephalon, ∼0.8 mm anterior to Ovoidalis and 0.8–1 mm ventromedial to VP (2/2 hemispheres) (Fig. 1A). These results were consistent with previous work and provided us with stereotactic coordinates for future injections and implants in STN.

Retrograde virus injection (scAAV9-GFP) in STN also resulted in back-labeled neurons into the part of VP that we and others recently showed projects to VTA (Fig. 1B, center) (26, 32, 33). The projection from STN to VP was demonstrated previously in zebra finches (31) and so we used this result as a confirmation that our injections were in the part of the diencephalon anatomically connected with VP. In addition, to test if VP-STN neurons were collaterals of VP-VTA neurons, birds were also injected with retrograde tracer CTB647 in VTA bilaterally (n = 4 hemispheres). We carefully inspected all labeled slices and failed to observe colabeling (Fig. 1B, center), suggesting that independent populations of VP neurons project to STN and VTA (4/4 hemispheres). We also noted that most of the VP-STN neurons (green in Fig. 1B, center) were more posterior to the VP-VTA neuron population (magenta in Fig. 1B, center). Although we failed to observe colabeled cells in VP, we cannot completely rule out the possibility, since the retrograde virus used in our study is a sparse expressing one (32).

Interestingly, following STN retrograde viral injections, we also discovered labeled cells in the part of auditory pallium, ventral anterior intermediate arcopallium (AIV) that projects to VTA (4/4 hemispheres). To test if AIV neurons that project to VTA also project to STN, we examined AIV neuron labeling in hemispheres doubly injected with scAAV9-GFP in STN and CTB647 in VTA. Colabeled cells were observed in AIV, suggesting that a population of AIV neurons that projects to VTA also projects to STN (Fig. 1B, right). Given the sparse expression of the virus and consequently GFP-labeled cells in AIV, we manually counted the number of AIV-STN cells observed across all slices in each hemisphere. We observed a total of 43 AIV-STN cells across four hemispheres out of which seven were colabeled with CTB647 (5/33 in 1 bird, 2/10 in the other), suggesting a population of AIV-VTA cells that send axon collaterals to STN (Fig. 1D). The disparity in the total number of GFP-labeled cells and colabeled cells across the two birds could be a result of small differences in the injection locations in either STN or VTA or both (injection volumes were 70 nL in STN and 50 nL in VTA). AIV is known to send auditory error signals to VTA during singing (33, 45); these anatomical data suggest that a copy of these error signals could also reach STN.

Following retrograde viral injections into STN, we also observed GFP-labeled cells in the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA), the primary vocal motor cortical nucleus of the song system (Fig. 1C). We observed 24 GFP-labeled cells and GFP-labeled axons in RA across three hemispheres, as well as labeled axons in the fourth hemisphere (Fig. 1D). This projection is reminiscent of the “hyperdirect pathway” observed in mammals where there are direct projections from the cortex to the STN that bypasses the striatum (3). Although the injection site in STN is close to the fibers of passage from RA to the brainstem vocal motor nucleus, the virus used in our study is only taken up by axon terminals and not fibers of passage (32, 37). Thus, we can preclude the possibility of the labeling in RA arising as a result of fiber uptake of virus.

The projection from RA to STN raises the possibility that the STN receives information about song timing during singing. In addition, past work showed that both AIV and VP project to VTA and exhibit performance evaluation signals during singing (32, 45). The discovery that both these song evaluative areas along with a key song production area also project to STN suggest that the STN could play a role in song evaluation and/or learning through its downstream projections.

Songbird STN Projects to VTA and Activates VTA Neurons

Based on STN connectivity in mammals, we hypothesized that songbird STN projects to VTA and specifically wondered if STN projects to the part of VTA that projects to Area X, the singing-related part of the songbird BG. To test this hypothesis, we first injected anterograde virus HSV-mCherry in STN and CTB488 in Area X to label STN axons and Area X-projecting neurons, respectively. STN axons overlapped with VTAx neurons (Fig. 1E). Imaging with confocal microscopy further allowed us to visualize STN axon in close proximity to VTAx neurons and dendrites (Fig. 1E). Although confirmation of actual synaptic contacts would require electron microscopy, these anatomical findings are consistent with the known STN-DA connectivity in mammals (13, 15, 46, 47), consistent with general conservation of BG anatomy across vertebrates (48, 49).

To test for functional connectivity between STN and VTA, we performed mapping experiments in anaesthetized birds (n = 8 birds; Fig. 2A). A recording electrode was used to record VTA neurons and bipolar stimulating electrodes were implanted in both Area X and in STN. Stimulation of Area X was used to antidromically identify Area X-projecting VTA neurons, which were confirmed by collision testing (n = 7; Fig. 2B) (38). Stimulation of STN was used to test for orthodromic responses in VTA neurons. In the example traces shown in Fig. 2B, the spontaneous spikes and the antidromic spikes are labeled in black. The trials on which the spontaneous spike underwent collision (red) are evinced from the absence of a red antidromic spike following the stimulation. Only those spontaneous spikes that occurred within a certain time window before or after stimulation underwent collision. VTA neurons that did not exhibit antidromic response to Area X stimulation were categorized as VTAother neurons (n = 6). These VTAother neurons may be DA neurons projecting to areas other than Area X or GABA neurons.

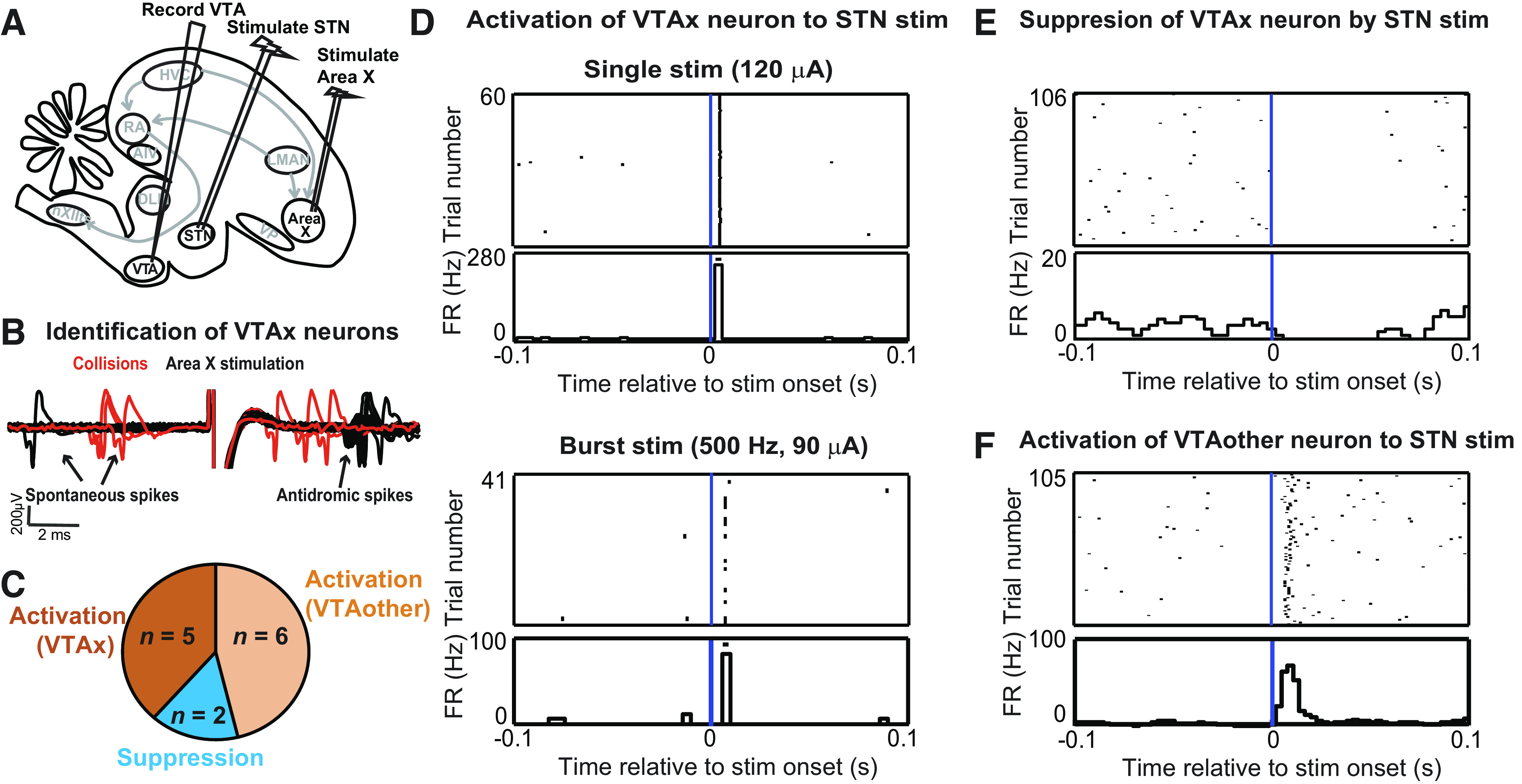

Figure 2.

STN stimulation activates VTA neurons including Area X-projecting VTA neurons. A: bipolar stimulating electrodes were implanted in Area X and STN in anaesthetized birds to test the effect of STN microstimulation on the firing of VTA neurons. B: all VTA neurons recorded were tested to see if they were Area X-projecting neurons by collision testing of spontaneous spikes with antidromic spikes generated by Area X stimulation. Collision events are highlighted in red. VTA neurons were then classified as either X-projectors (VTAx) or nonprojectors (VTAother). C: a total of 13 VTA neurons were recorded, out of which 7 were identified as VTAx. Five VTAx neurons were activated by STN stimulation, whereas 2 were suppressed. All VTAother neurons exhibited activation to STN stimulation. D: example of a VTAx neuron exhibiting a short-latency (4 ms) activation to STN stimulation (top). The threshold current for activation with single-pulse stimulation was 100 μA. Response of the neuron to a 2-pulse stimulation (interpulse interval, 2 ms) at subthreshold current (90 μA) is shown at the bottom. E: example of a VTAx neuron suppressed by STN stimulation (150 μA). F: example of a VTAother neuron activated by STN stimulation (120 μA) at a latency of 5.5 ms. FR, firing rate; stim, stimulation; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

All VTA neurons were tested for response to STN stimulation. STN stimulation mostly caused activations (Fig. 2C), including activation of antidromically identified VTAx neurons (Fig. 2D). Neurons that exhibited activation to a single pulse of STN stimulation were further tested with bursts of STN stimulation at subthreshold intensities (i.e., current amplitudes lower than that required for activation with single-pulse STN stimulation) to distinguish between antidromic and orthodromic response (Fig. 2D, bottom). By this criterion and the absence of any observed antidromic collisions, we concluded that the response of the VTAx neurons to STN stimulation, although highly short latency and precise, was likely orthodromic. Most VTAx neurons exhibited a short latency (2.5 ± 0.61 ms, mean ± SD) activation to STN stimulation (n = 5/7); two neurons exhibited suppressions (example in Fig. 2E). All VTAother neurons exhibited a short-latency (mean ± SD, 3.25 ± 1.13 ms) activation to STN stimulation (example in Fig. 2F).

Together, these results suggest that STN projects to VTA and can modulate the firing of VTA neurons, including VTAx neurons that have been shown to exhibit performance error signals in singing birds. Although we kept the current through STN stimulating electrodes low (<150 μA), we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the STN stimulation also activated some fibers of passage coursing through the diencephalon en route to VTA, including projections from AIV and VP.

A Small Fraction of STN Neurons Exhibit Song- and Evaluation-Related Signals in Singing Birds

We next investigated if STN neurons exhibit any singing- and/or evaluation-related signals. We recorded 62 neurons in seven birds while controlling perceived auditory feedback with syllable-targeted DAF, as previously described (32, 38). In four of the seven birds, we also recorded movements with head-mounted accelerometers. To test for singing-related changes in firing, we examined for significant firing rate changes during singing, for syllable-locked timing, and for DAF-associated error responses. Most STN neurons were not singing related based on these criteria (51/62).

However, a small population of STN neurons (n = 11 out of 62 recorded) in singing birds exhibited time-locked firing during singing (n = 9) or performance evaluation signaling (n = 2). The firing rate of the time-locked neurons during singing ranged from 2.3 to 92 Hz. Out of the nine song-locked neurons, four neurons exhibited a high-peak firing rate during singing (>100 Hz) and mean firing rate (during singing) 59.7 ± 23.3 Hz (mean ± SD). They also exhibited a large increase in firing at the onset of motif and then precise time-locked firing within the song (example in Fig. 3A). Four other neurons exhibited mostly low firing rates to almost no firing outside of singing and precise time-locked firing with increase in firing rate during singing (mean ± SD, 7.3 ± 4.7 Hz) (example in Fig. 3B). One of the neurons exhibited a precise, sparse firing during singing (Fig. 3C). None of these neurons exhibited any difference in firing rates between distorted (DAF) and undistorted (no DAF) trials. All these song timing neurons exhibited a significant difference in firing rate during singing compared with silent periods (n = 9, P < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) (blue circles, Fig. 3F).

The precision of time-locked firing was measured by computing the intermotif correlation coefficient (IMCC) (see MATERIALS AND methods). Significance of the IMCC values were assessed by generating “new” IMCC values from shuffled data (random, circular time-shifted spike trains) and a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to compare the actual IMCC value with the new IMCC value of the shuffled data (32). All nine neurons exhibited significant IMCC values (mean ± SD, 0.25 ± 0.26; range, 0.04 to 0.76, P < 0.001). The high firing rate neurons exhibited a higher value of IMCC.

Two STN neurons exhibited performance evaluation signals with suppression of firing following DAF during distorted renditions and increased firing following absence of DAF during undistorted renditions (Fig. 3, D and E), similar to VTAx DA neurons (38). Like VTAx neurons, they did not exhibit any firing rate modulations to the DAF sound presented outside singing, no significant song-locked activity (IMCC < 0.01, P > 0.05) and no significant difference in firing rates during and outside song (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) (red circles, Fig. 3F). Singing- and nonsinging-related neurons were spatially intermingled (Fig. 5A).

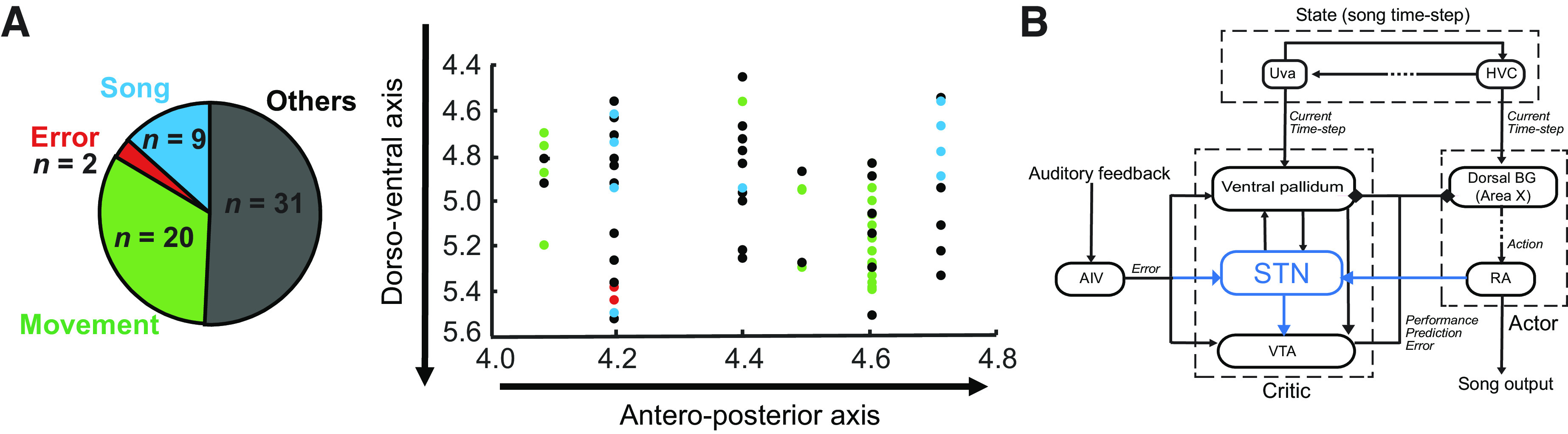

Figure 5.

STN in zebra finches. A: we recorded a total of 62 STN neurons in singing birds. The anteroposterior coordinates of the implant and the dorsoventral coordinates of each recorded neuron have been plotted on the right (the mediolateral coordinates of the implants were not varied across bird). We found that the recorded neurons were spatially distributed along these axes with no clustering of the functional types. B: based on the results from anatomy and electrophysiology, we hypothesize that the STN is part of critic circuit in songbirds. Paralleling the anatomical connectivity of the VP that has been demonstrated to be involved in song learning in prior studies, we discovered in our study the following connections (blue): STN to VTA, RA to STN, and AIV to STN. This discovery along with the song-related neural signals in finch STN allowed us to place STN in a functional microcircuitry subserving the evaluative pathway of the “actor-critic” model of song learning. AIV, ventral anterior intermediate arcopallium; BG, basal ganglia; RA, robust nucleus of the arcopallium; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VP, ventral pallidum; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Songbird STN Neurons Exhibit Movement-Related Discharge

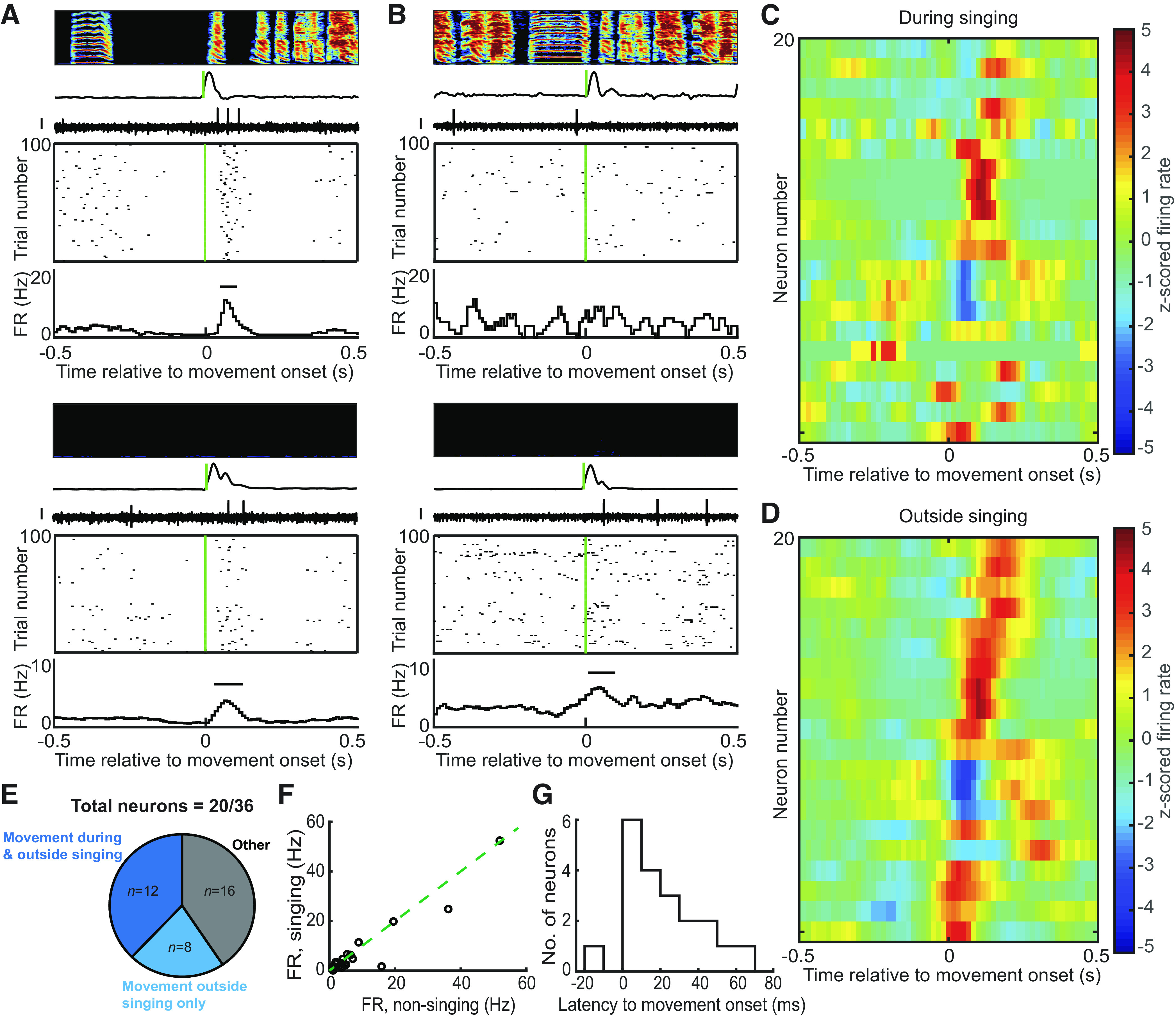

A total of 36 neurons were recorded from birds (n = 4) implanted with headstages mounted with accelerometers, facilitating the assessment of movement-related activity in the finch STN. Out of these neurons, 20 showed significant firing rate changes following movement onsets/offsets and eight of these showed that movement onset aligned firing rate increase only outside singing. The firing rates of these movement neurons ranged from 1 to 50 Hz with a mean firing rate outside singing, 9.12 ± 12.6 Hz (mean ± SD). Fourteen neurons that exhibited movement onset firing rate changes during both singing and nonsinging periods (example, Fig. 4A) did not have any significant difference between their firing rates outside singing versus during singing (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Fig. 4F). The other eight neurons had significantly different (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) firing rates outside singing (mean ± SD, 4.37 ± 4.8 Hz) compared with during singing (mean ± SD, 1.51 ± 0.9 Hz) and exhibited movement onset firing rate increase only outside singing (example, Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Songbird STN neurons exhibit movement-aligned firing rate changes. A: example of a neuron that exhibited movement onset increase in firing rate both during and outside singing. Top panel shows the spectrogram of the song with time-aligned smoothed rectified accelerometer signal and neural trace. The corresponding raster plot is shown below with the firing rate (FR in Hz) histogram. The bar in the histogram depicts significant change in firing rate (z-test, P < 0.05). Bottom panel shows the raster plot and firing rate histogram along with the neural trace and accelerometer signal corresponding to nonsinging period. Scale bar on all neural traces is 0.1 mV. B: example of a neuron that exhibited no movement-aligned firing rate changes during song (top) and movement onset firing rate increase during nonsinging period (bottom). C and D: the z-scored firing rate change was plotted for all neurons (n = 20) during singing (C) and outside singing (D). Three neurons were suppressed following movement onset, whereas the others showed increased firing following movement onset with a response duration in the range of hundreds of ms. E: a total of 36 neurons were recorded from birds with headstages mounted with accelerometers. Out of these, 20 neurons exhibited significant movement-aligned firing rate changes and 12 of these did so during both singing and nonsinging periods. Eight neurons were movement aligned only outside singing. F: most of the neurons exhibited low firing rates and did not show any significant difference between firing rate during singing and outside singing. G: latencies to movement onset were computed based on the window of significant firing rate change in the firing rate histogram. A histogram of the latencies has been plotted. Latency values ranged from −15 to 65 ms, with most of the neurons exhibiting significant firing rate change following movement onset. STN, subthalamic nucleus.

A heat map of the z-scored firing rate change for all neurons aligned to movement onset showed a variability in latency to response, but most of the response was following movement onset (Fig. 4, C and D). The latency to movement onset varied from −15 to 55 ms (Fig. 4G) with a median latency of 15 ms. Four of these neurons exhibited a movement onset aligned decrease in firing rate. Our results showing movement-aligned firing rate modulation of finch STN neurons is consistent with the known motor functions of the mammalian STN (1, 9, 50, 51).

In addition, neurons in other areas of the finch brain, namely, VTA and VP have been shown to contain neurons that encode movement and display differential encoding of movement depending on the behavioral state of the animal (singing vs. nonsinging) (42). Our results suggest that the finch STN also contains a population of neurons encoding movement independent of state and another smaller population that exhibits singing-related gating of movement signaling. None of the movement-related neurons exhibited any song-locked firing rate modulation according to the criteria defined previously (IMCC < 0.01, P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

By combining anatomical and functional circuit mapping and electrophysiology in singing birds, we found that the STN is interconnected with several structures involved in song evaluation (AIV, VP, and VTA) and song production (RA). We also discovered that a small fraction of STN neurons exhibited singing-related signals. This first-ever investigation into the neural signals in the songbird STN expands our understanding of the singing-related portions of the songbird brain beyond the classic song system.

Historically, the song system was divided into two pathways: a motor pathway (from HVC-RA) necessary for adult song production and an anterior forebrain pathway (a BG-thalamo-cortical loop) necessary for song learning and babbling but not adult song production (25, 27, 28, 52–55). Yet, recent studies have expanded the territories of the songbird brain implicated in learning. First, midbrain DA neurons in the part of VTA that projects to Area X encode auditory error signals during singing, and, importantly, these signals are capable of driving learning (36–38, 56). Second, anatomical studies identified two inputs to VTA: AIV, an auditory cortical area and VP, BG region ventromedial to Area X (26, 45, 57). Lesion studies showed that both of these forebrain inputs to VTA are necessary for song learning (but not production) (32, 45, 58). Electrophysiological studies showed that both AIV and VP send error signals to VTA during singing (32, 45) and optogenetic studies showed that photoactivation of either of these inputs to VTA reinforces vocal fluctuations but does not drive real-time changes to song (33, 37). Together, these data implicate VTA and its inputs as part of a critic pathway that evaluates but does not produce song (34).

Interestingly, our anatomical findings place songbird STN in this critic pathway for song learning but not in the “actor” pathway for vocal production (Fig. 5B). First, the STN projects both to VP and to VTA—two structures whose lesions impair learning but not the ability to sing (32, 56). Second, STN receives inputs from VP and AIV, two areas implicated in performance error processing. Third, some STN neurons exhibited auditory error signals during singing, raising the possibility that STN could contribute to error processing in target VTA neurons. Finally, most STN neurons exhibited movement-locked activity, yet singing- and movement-related neurons were spatially intermingled. Thus, unlike the nuclei of the song system, where all neurons are singing related, the songbird STN may serve more general motor evaluation functions. Notably, a similar intermixing of singing- and nonsinging-related signals were observed in the learning-associated structures VP and the VTA, and both structures exhibited a similarly small fraction of neurons that encoded song timing or error (32, 38, 42).

How midbrain DA neurons use these various inputs to compute song evaluation signals [or more generally, reward prediction error (RPE) signals] is still an open question. Although previous studies showed that Area X-projecting VTA (VTA-X) neurons receive inputs from at least two forebrain inputs: AIV and VP, both with significant roles in song evaluation (26, 32, 33, 37, 45, 59), we note that these two inputs alone may not be sufficient to explain the bursts and pauses that VTAx neurons exhibit following better- and worse-than predicted song outcomes. Specifically, in mammals, direct excitatory inputs onto DA neurons are important for DA phasic burst firing; mice with N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors knocked out from DA neurons exhibit impaired bursting and learning (14, 60). Also, a recent whole brain mapping study of inputs to DA neurons in mice revealed that the STN provides DA neurons with the major source of glutamatergic input (14, 15). Notably, in songbirds, both AIV and VP stimulation tend to inhibit DA neuronal discharge (32, 33), and the VP-VTA projection is GABAergic. Our results here, along with previous anatomical and lesion studies (30, 31), place the songbird STN in an evolutionary conserved subcortical microcircuitry that could provide DA neurons with excitatory input. Given that the STN receives inputs from both song generation and song evaluative circuits, we hypothesize a possible role for STN (6, 12), whereby it can use the information about the song timing and predicted song quality (32, 34) from these upstream areas to drive phasic bursts in DA neuron firing (note that we observed both activation and suppression of VTAx neurons in Fig. 2). Testing this idea would require recording DA activity in singing birds while suppressing activity specifically in the STN-VTA pathway. We hypothesize that the suppression of the STN-VTA pathway would result in the disappearance of the DA bursts following better-than-predicted song outcomes.

Although our findings support the idea that STN is part of the song evaluation system upstream of the VTA, lesion studies that would firmly test the causal role of STN in song learning were unfortunately not possible. We attempted to bilaterally lesion STN in juvenile birds to assess its role in song learning but 4/4 lesioned birds exhibited such dramatic movement impairments post-operatively that they were euthanized. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that unilateral lesions of STN causes motor deficits in birds, similar to mammals (30). Such severe postlesion motor impairments prevent the assessment of any other learning (song learning in this case) deficits. Future studies using cell type-specific viral targeting methods to specifically ablate or optogenetically regulate VTA-projecting STN neurons in singing birds may be able to causally test the necessity of this projection for DA RPE signaling and song learning (33, 36).

GRANTS

This work was supported by funding from NIH R01NS094667.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.H.G. and A.D. conceived and designed research; A.D. performed experiments; A.D. analyzed data; A.D. and J.H.G. interpreted results of experiments; A.D. prepared figures; A.D. drafted manuscript; A.D. and J.H.G. edited and revised manuscript; A.D. and J.H.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Archana Podury for help with anatomy and members of the Goldberg lab for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fife KH, Gutierrez-Reed NA, Zell V, Bailly J, Lewis CM, Aron AR, Hnasko TS. Causal role for the subthalamic nucleus in interrupting behavior. eLife 6: e27689, 2017. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank MJ. Hold your horses: a dynamic computational role for the subthalamic nucleus in decision making. Neural Netw 19: 1120–1136, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nambu A, Tokuno H, Takada M. Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ pathway. Neurosci Res 43: 111–117, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt R, Leventhal DK, Mallet N, Chen F, Berke JD. Canceling actions involves a race between basal ganglia pathways. Nat Neurosci 16: 1118–1124, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nn.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wessel JR, Jenkinson N, Brittain J-S, Voets SHEM, Aziz TZ, Aron AR. Surprise disrupts cognition via a fronto-basal ganglia suppressive mechanism. Nat Commun 7: 11195, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbier M, Risold P-Y. Understanding the significance of the hypothalamic nature of the subthalamic nucleus. eNeuro 8: ENEURO.0116-21.2021, 2021.doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0116-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benarroch EE. Subthalamic nucleus and its connections: anatomic substrate for the network effects of deep brain stimulation. Neurology 70: 1991–1995, 2008. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313022.39329.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank MJ, Samanta J, Moustafa AA, Sherman SJ. Hold your horses: impulsivity, deep brain stimulation, and medication in parkinsonism. Science 318: 1309–1312, 2007. doi: 10.1126/science.1146157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamani C, Saint-Cyr JA, Fraser J, Kaplitt M, Lozano AM. The subthalamic nucleus in the context of movement disorders. Brain 127: 4–20, 2004. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breysse E, Pelloux Y, Baunez C. The good and bad differentially encoded within the subthalamic nucleus in rats. eNeuro 2: ENEURO.0014-15.2015, 2015.doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0014-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lardeux S, Pernaud R, Paleressompoulle D, Baunez C. Beyond the reward pathway: coding reward magnitude and error in the rat subthalamic nucleus. J Neurophysiol 102: 2526–2537, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.91009.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temel Y, Blokland A, Steinbusch HW, Visser-Vandewalle V. The functional role of the subthalamic nucleus in cognitive and limbic circuits. Prog Neurobiol 76: 393–413, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa SK, Cohen JY, Hwang D, Uchida N, Watabe-Uchida M. Organization of monosynaptic inputs to the serotonin and dopamine neuromodulatory systems. Cell Rep 8: 1105–1118, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian J, Huang R, Cohen JY, Osakada F, Kobak D, Machens CK, Callaway EM, Uchida N, Watabe-Uchida M. Distributed and mixed information in monosynaptic inputs to dopamine neurons. Neuron 91: 1374–1389, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watabe-Uchida M, Zhu L, Ogawa SK, Vamanrao A, Uchida N. Whole-brain mapping of direct inputs to midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron 74: 858–873, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruet N, Windels F, Bertrand A, Feuerstein C, Poupard A, Savasta M. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus increases the extracellular contents of striatal dopamine in normal and partially dopaminergic denervated rats. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60: 15–24, 2001. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meissner W, Harnack D, Paul G, Reum T, Sohr R, Morgenstern R, Kupsch A. Deep brain stimulation of subthalamic neurons increases striatal dopamine metabolism and induces contralateral circling in freely moving 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Neurosci Lett 328: 105–108, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meissner W, Harnack D, Reese R, Paul G, Reum T, Ansorge M, Kusserow H, Winter C, Morgenstern R, Kupsch A. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus enhances striatal dopamine release and metabolism in rats. J Neurochem 85: 601–609, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul G, Reum T, Meissner W, Marburger A, Sohr R, Morgenstern R, Kupsch A. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus influences striatal dopaminergic metabolism in the naive rat. NeuroReport 11: 441–444, 2000.doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baunez C, Dias C, Cador M, Amalric M. The subthalamic nucleus exerts opposite control on cocaine and ‘natural’ rewards. Nat Neurosci 8: 484–489, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nn1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baunez C, Amalric M, Robbins TW. Enhanced food-related motivation after bilateral lesions of the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci 22: 562–568, 2002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00562.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wouwe NC, Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WPM, Band GPH, Abisogun A, Elias WJ, Frysinger R, Wylie SA. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus improves reward-based decision-learning in Parkinson’s disease. Front Hum Neurosci 5: 30, 2011. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275: 1593–1599, 1997. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glimcher PW. Understanding dopamine and reinforcement learning: The dopamine reward prediction error hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, Suppl 3: 15647–15654, 2011. [Erratum in Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 17568–17569, 2011]. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014269108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fee MS, Goldberg JH. A hypothesis for basal ganglia-dependent reinforcement learning in the songbird. Neuroscience 198: 152–170, 2011. [Erratum in Neuroscience 255: 301, 2013]. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale SD, Person AL, Perkel DJ. A novel basal ganglia pathway forms a loop linking a vocal learning circuit with its dopaminergic input. J Comp Neurol 508: 824–839, 2008. doi: 10.1002/cne.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doupe AJ, Perkel DJ, Reiner A, Stern EA. Birdbrains could teach basal ganglia research a new song. Trends Neurosci 28: 353–363, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gale SD, Perkel DJ. Anatomy of a songbird basal ganglia circuit essential for vocal learning and plasticity. J Chem Neuroanat 39: 124–131, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colquitt BM, Merullo DP, Konopka G, Roberts TF, Brainard MS. Cellular transcriptomics reveals evolutionary identities of songbird vocal circuits. Science 371: eabd9704, 2021. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiao Y, Medina L, Veenman CL, Toledo C, Puelles L, Reiner A. Identification of the anterior nucleus of the ansa lenticularis in birds as the homolog of the mammalian subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci 20: 6998–7010, 2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06998.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Person AL, Gale SD, Farries MA, Perkel DJ. Organization of the songbird basal ganglia, including area X. J Comp Neurol 508: 840–866, 2008. doi: 10.1002/cne.21699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen R, Puzerey PA, Roeser AC, Riccelli TE, Podury A, Maher K, Farhang AR, Goldberg JH. Songbird ventral pallidum sends diverse performance error signals to dopaminergic midbrain. Neuron 103: 266–276, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kearney MG, Warren TL, Hisey E, Qi J, Mooney R. Discrete evaluative and premotor circuits enable vocal learning in songbirds. Neuron 104: 559–575.e6, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen R, Goldberg JH. Actor-critic reinforcement learning in the songbird. Curr Opin Neurobiol 65: 1–9, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding L, Perkel DJ. Long-term potentiation in an avian basal ganglia nucleus essential for vocal learning. J Neurosci 24: 488–494, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4358-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hisey E, Kearney MG, Mooney R. A common neural circuit mechanism for internally guided and externally reinforced forms of motor learning. Nat Neurosci 21: 589–597, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0092-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao L, Chattree G, Oscos FG, Cao M, Wanat MJ, Roberts TF. A basal ganglia circuit sufficient to guide birdsong learning. Neuron 98: 208–221.e5, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gadagkar V, Puzerey PA, Chen R, Baird-Daniel E, Farhang AR, Goldberg JH. Dopamine neurons encode performance error in singing birds. Science 354: 1278–1282, 2016. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldberg JH, Adler A, Bergman H, Fee MS. Singing-related neural activity distinguishes two putative pallidal cell types in the songbird basal ganglia: comparison to the primate internal and external pallidal segments. J Neurosci 30: 7088–7098, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0168-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kao MH, Wright BD, Doupe AJ. Neurons in a forebrain nucleus required for vocal plasticity rapidly switch between precise firing and variable bursting depending on social context. J Neurosci 28: 13232–13247, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ölveczky BP, Andalman AS, Fee MS. Vocal experimentation in the juvenile songbird requires a basal ganglia circuit. PLoS Biol 3: e153, 2005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen R, Gadagkar V, Roeser AC, Puzerey PA, Goldberg JH. Movement signaling in ventral pallidum and dopaminergic midbrain is gated by behavioral state in singing birds. J Neurophysiol 125: 2219–2227, 2021. doi: 10.1152/jn.00110.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groenewegen HJ, Berendse HW, Haber SN. Organization of the output of the ventral striatopallidal system in the rat: ventral pallidal efferents. Neuroscience 57: 113–142, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90115-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haber SN, Lynd-Balta E, Mitchell SJ. The organization of the descending ventral pallidal projections in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 329: 111–128, 1993. doi: 10.1002/cne.903290108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandelblat-Cerf Y, Las L, Denisenko N, Fee MS. A role for descending auditory cortical projections in songbird vocal learning. eLife 3: e02152, 2014. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joel D, Weiner I. The connections of the primate subthalamic nucleus: indirect pathways and the open-interconnected scheme of basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuitry. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 23: 62–78, 1997. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Der Kooy D, Hattori T. Single subthalamic nucleus neurons project to both the globus pallidus and substantia nigra in rat. J Comp Neurol 192: 751–768, 1980. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grillner S, Robertson B, Stephenson-Jones M. The evolutionary origin of the vertebrate basal ganglia and its role in action selection. J Physiol 591: 5425–5431, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.246660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reiner A, Medina L, Veenman CL. Structural and functional evolution of the basal ganglia in vertebrates. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 28: 235–285, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Georgopoulos AP, DeLong MR, Crutcher MD. Relations between parameters of step-tracking movements and single cell discharge in the globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus of the behaving monkey. J Neurosci 3: 1586–1598, 1983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-08-01586.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen W, de Hemptinne C, Miller AM, Leibbrand M, Little SJ, Lim DA, Larson PS, Starr PA. Prefrontal-subthalamic hyperdirect pathway modulates movement inhibition in humans. Neuron 106: 579–588.e3, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hahnloser RHR, Kozhevnikov AA, Fee MS. An ultra-sparse code underlies the generation of neural sequences in a songbird. Nature 419: 65–70, 2002. [Erratum in Nature 421: 294, 2003]. doi: 10.1038/nature00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kozhevnikov AA, Fee MS. Singing-related activity of identified HVC neurons in the zebra finch. J Neurophysiol 97: 4271–4283, 2007. doi: 10.1152/jn.00952.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aronov D, Andalman AS, Fee MS. A specialized forebrain circuit for vocal babbling in the juvenile songbird. Science 320: 630–634, 2008. doi: 10.1126/science.1155140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brainard MS, Doupe AJ. Interruption of a basal ganglia–forebrain circuit prevents plasticity of learned vocalizations. Nature 404: 762–766, 2000.doi: 10.1038/35008083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffmann LA, Saravanan V, Wood AN, He L, Sober SJ. Dopaminergic contributions to vocal learning. J Neurosci 36: 2176–2189, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3883-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gale SD, Perkel DJ. A basal ganglia pathway drives selective auditory responses in songbird dopaminergic neurons via disinhibition. J Neurosci 30: 1027–1037, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3585-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Achiro JM, Shen J, Bottjer SW. Neural activity in cortico-basal ganglia circuits of juvenile songbirds encodes performance during goal-directed learning. eLife 6: e26973, 2017. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mello CV, Vates E, Okuhata S, Nottebohm F. Descending auditory pathways in the adult male zebra finch (Taeniopygia Guttata). J Comp Neurol 395: 137–160, 1998.doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zweifel LS, Parker JG, Lobb CJ, Rainwater A, Wall VZ, Fadok JP, Darvas M, Kim MJ, Mizumori SJ, Paladini CA, Phillips PE, Palmiter RD. Disruption of NMDAR-dependent burst firing by dopamine neurons provides selective assessment of phasic dopamine-dependent behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7281–7288, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]