Abstract

Mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation plays an important role in hepatic insulin resistance. However, the precise mechanisms by which MR activation promotes hepatic insulin resistance remains unclear. Therefore, we sought to investigate the roles and mechanisms by which MR activation promotes Western diet (WD)-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Six-week-old C57BL6J mice were fed either mouse chow or a WD, high in saturated fat and refined carbohydrates, with or without the MR antagonist spironolactone (1 mg/kg/day) for 16 wk. WD feeding resulted in systemic insulin resistance at 8 and 16 wk. WD also induced impaired hepatic insulin metabolic signaling via phosphoinositide 3-kinases/protein kinase B pathways, which was associated with increased hepatic CD36, fatty acid transport proteins, fatty acid-binding protein-1, and hepatic steatosis. Meanwhile, consumption of a WD-induced hepatic mitochondria dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses. These abnormalities occurring in response to WD feeding were blunted with spironolactone treatment. Moreover, spironolactone promoted white adipose tissue browning and hepatic glucose transporter type 4 expression. These data suggest that enhanced hepatic MR signaling mediates diet-induced hepatic steatosis and dysregulation of adipose tissue browning, and subsequent hepatic mitochondria dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, as well as hepatic insulin resistance.

Keywords: hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, mineralocorticoid receptor, mitochondria dysfunction, obesity

INTRODUCTION

It is well accepted that obesity contributes to an increased risk for insulin resistance and development of type 2 diabetes (1, 2). Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicate that 85.2% of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese (3), promoted by consumption of a Western diet (WD) high in saturated fat and refined carbohydrates (4, 5). Recent experimental data in human studies indicate that aldosterone levels are increased in overweight individuals and under conditions of overnutrition (6), and further preclinical data indicate that diet-induced obesity is associated with enhanced tissue mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) activation (7–10). In this regard, under conditions of insulin resistance the liver plays an integral role in glucose production and its metabolic responses to insulin can be impaired, e.g., hepatic insulin resistance. However, the role of the MR in hepatic insulin resistance is unknown.

Aldosterone is traditionally regarded as the primary ligand for MRs and has been considered a “renal” hormone that modulates plasma volume, electrolyte homeostasis, and blood pressure (11–14). Mounting data support the notion that aldosterone has extrarenal actions in other tissues including hepatocytes, adipose tissue, as well as cardiovascular cells (11–14). Studies conducted by our group and others have demonstrated that excessive aldosterone stimulation of MRs is involved in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance (15–17). For instance, antagonism of MR signaling prevented high-fat diet-induced development of metabolic abnormalities by reducing body fat and improving glucose tolerance in mice (16). In addition, it was reported that MR antagonism inhibited hepatic inflammation and enhanced gluconeogenesis, resulting in improvement in glucose and lipid metabolism (17). Thus, excessive tissue-specific MR activation is related to hepatic and systemic insulin resistance. However, the precise mechanisms by which enhanced activation of MR induces insulin resistance and diabetes in association with diet-induced obesity remains to be elucidated. We hypothesized that consumption of a WD would induce MR-dependent hepatic insulin resistance via increased hepatic steatosis, dysregulation of white adipose tissue browning, and associated hepatic mitochondria dysfunction, excessive oxidative stress, and inflammation. The corollary to this hypothesis was that inhibition of hepatic MR activation with spironolactone will attenuate diet-induced hepatic pathophysiological changes and associated systemic and tissue insulin resistance.

METHODS

Ethics and Approvals

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Missouri. The University of Missouri research unit is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All experiments were randomized and performed in a blinded manner when possible by the investigators.

Animals and Experimental Design

Five-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were procured from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). When mice were 6 wk of age they were randomly assigned to one of four groups that include mice fed a chow diet with a control placebo pellet (CD) or a spironolactone pellet (CDSp), and mice fed a WD, containing high fat (46%), high carbohydrate as sucrose (17.5%), and high fructose corn syrup (17.5%), with a control pellet (WD) or a spironolactone pellet (WDSp). Spironolactone was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day via a slow-release pellet (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) implanted in the scapular region on the back as described in our previous study (18). The rationale for choosing a dose of 1 mg/kg/day spironolactone was based on established evidence that this dose inhibits 35% of in vivo aldosterone binding to the MR without reducing blood pressure and antiandrogenic and progestogenic effects (19).

Structural, Biochemical Parameters, Assessment of Whole Body Insulin Sensitivity

After 16 wk of feeding, mice underwent body composition analysis for whole body fat mass, lean mass, and total body water using an EchoMRI-500 for quantitative magnetic resonance analysis (Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX) as previously described (7). Blood samples were collected at euthanasia, and plasma was separated and sent to the University of Missouri Small Animal Veterinary Clinic for the blood chemistry tests (7). The ELISA kits were used to detect plasma-free fatty acids (FFAs) (No. MAK044, Sigma), leptin, and adiponectin (No. KMC2281, No. KMP0041, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed following a 5-h fast as previously described (20). Briefly, dextrose (1.5 g/kg) was injected intraperitoneally and the glucose excursion was monitored over time and compared between treatment groups. Blood samples were analyzed for glucose (AlphaTRACK, Abbott, IL) at time 0 and 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min following dextrose injection (20).

Western Blot and Real-Time PCR

Protein concentrations of liver tissue homogenates were measured as previously described (7, 10). To quantify relevant insulin signaling proteins, Western blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against p85-phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/PI3K, p-protein kinase B (Akt)/Akt, CD36, glucose transporter type 4 (Glut4), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:1,000 dilution, No. 17366/No. 4275#5174 s, No. 9271/No. 9272, No. 14347, No. 2213, No. 5174 s, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1) (1:1,000 dilution, No. u6382, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence, and images were recorded using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS image analysis system (7, 10).

Liver and epi-abdominal fat tissues were homogenized in QIAzol (Qiagen, MD) and total RNA was isolated using a Qiagen microRNeasy Kit (Qiagen, MD) (7, 10). Purity and concentration were assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the Improm-II reverse transcription kit (Promega, Madison, W) and quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primer sequences were listed in Table 1. PCR cycling conditions were 5 min at 95°C for initial denaturation, 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Each real-time PCR was carried out using three individual samples in triplicate, and the threshold cycle values were averaged. Calculations of relative normalized gene expression were performed using Bio-Rad CFX manager software. Results were normalized against the housekeeping gene GAPDH (7, 10).

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for real-time PCR

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Fabp1 | CTTCTCCGGCAAGTACCAAT | CCTTGATGTCCTTCCCTTTCT |

| FATP | CAGTTGGACCCTAACTCAATGT | TTGAAGGTGCCTGTGGTATC |

| UCP-1 | GAGGTCGTGAAGGTCAGAATG | AAGCTTTCTGTGGTGGCTATAA |

| Dio2 | CTTCCTCCTAGATGCCTACAAAC | TCTCCGAGGCATAATTGTTACC |

| Adrb3 | ACAGGAATGCCACTCCAATC | GAGCATAGACGAAGAGCATCAC |

| Prdm16 | CACAAGTCCTACACGCAGTT | TTGTTGAGGGAGGAGGTAGT |

| UCP3 | TCAGTGAACAGGTGAGAGTCC | ATGCCTACAGAACCATCGCCA |

| CYTB | AGACAGTCCCACCCTCACAC | AAGAGAAGTAAGCCGAGGGC |

| NRF1 | GATCGTCTTGTCTGGGGAAA | GGTGACTGCGCTGTCTGATA |

| TFAM | GATGCTTATAGGGCGGAG | GCTGAACGAGGTCTTTTTGG |

| PGC1 | CCTGTGGATGAAGACGGATT | TAGCTGAGTGTTGGCTGGTG |

| NOX2 | CTTTGGTACAGCCAGTGAAGA | CCAGACAGACTTGAGAATGGAG |

| NOX4 | CTGGACCTTTGTGCCTTTATTG | AGGGATGATTGATGACTGAGATG |

| IL-6 | CTTCCATCCAGTTGCCTTCT | CTCCGACTTGTGAAGTGGTATAG |

| TNF-α | GCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGCTTG | CTGATGAGAGGGAGGCCATT |

| CD68 | ACACCTACAGCCACAGAAAG | GCAGGGTTATGAGTGACAGTT |

| CD86 | GACCGTTGTGTGTGTTCTGG | GATGAGCAGCATCACAAGGA |

| GAPDH | GGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTATGA | TCCTCAGTGTAGCCCAAGA |

Immunohistochemistry and Transmission Electron Microscopy

The harvested liver and epi-abdominal fat samples were immersed in cryostat embedding media (OCT, optimal cutting temperature compound) and were transversely sectioned (5 μm slices) (7, 10). Tissue sections were incubated with antibodies to Glut4, UCP-1 (No. 2213, No. 14670, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) (Millipore, Billerica, MA), respectively. Oil Red O staining was performed on frozen liver sections to detect the presence of lipid droplets. Areas and the intensities of staining for Glut4, UCP-1, 3-NT, and lipid accumulation were quantified using MetaVue as described before (7, 10). For TEM of liver tissue, samples were prepared, sectioned, and stained as previously described (10). A JOEL 1400-EX transmission electron microscope (Joel Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was utilized to capture and analyze three fields randomly chosen per mouse (10).

Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as means ± SE. Differences in outcomes were determined using two-way ANOVA multiple-comparison analysis and Gabriel Students–Newman–Keuls posttest and were considered significant when P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Sigma Plot (version 12) software (Systat Software).

RESULTS

Impact of MR Antagonism in WD-Fed Mice

Sixteen weeks of WD feeding induced increases in body weight, liver weight, total fat mass, and epi-abdominal fat without significant alterations in lean mass. Meanwhile, WD consumption also induced increases in plasma and liver FFAs, leptin, cholesterol, and alkaline phosphate levels. However, spironolactone inhibited WD-induced elevated liver FFA and plasma leptin levels. There were no significant differences in body weight, fat mass, liver weight, epi-abdominal fat, plasma FFA, cholesterol, and alkaline phosphates levels in WD-fed mice with or without spironolactone treatment. Of note, there were also no significant differences in lean mass, adiponectin, triglyceride, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyltransferase, and insulin levels between any of the groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of spironolactone on characteristics of mice fed a Western diet

| Measures | CD | CDSp | WD | WDSp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 19.32 ± 0.26 | 21.01 ± 0.49 | 26.14 ± 1.01† | 26.15 ± 1.69† |

| Fat mass, g | 2.68 ± 0.27 | 2.61 ± 0.44 | 8.07 ± 1.15† | 8.08 ± 1.32† |

| Lean mass, g | 17.25 ± 0.20 | 17.26 ± 0.44 | 17.58 ± 0.29 | 16.78 ± 0.28 |

| Liver weight, g | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 0.97 ± 0.02† | 0.99 ± 0.06† |

| Epi-abdominal fat, g | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.11† | 1.11 ± 0.20† |

| Plasma FFA, mmol | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 1.05 ± 0.12† | 0.86 ± 0.10 |

| Liver FFA, mmol/100 mg | 1.48 ± 0.06 | 1.32 ± 0.09 | 2.14 ± 0.19† | 1.61 ± 0.15‡ |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 6.38 ± 0.22 | 6.14 ± 0.18 | 16.37 ± 1.14† | 10.52 ± 0.73‡ |

| Adiponectin, µg/mL | 8.71 ± 0.21 | 8.95 ± 0.17 | 7.91 ± 0.48 | 8.01 ± 0.15 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 64.75 ± 4.12 | 70.63 ± 4.84 | 98.38 ± 6.73† | 98.88 ± 9.56† |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 64 ± 7.26 | 61.63 ± 6.38 | 68.25 ± 5.97 | 64 ± 0.5.25 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 32.25 ± 5.84 | 32.63 ± 5.54 | 36.13 ± 3.31 | 39.75 ± 3.69 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 58.5 ± 3.79 | 65.5 ± 4.49 | 78 ± 9.89† | 77.5 ± 1.73† |

| γ-glutamyl transferase, U/L | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 |

| Insulin, ng/mL | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.21 ± 0.03 |

Values are represented as means ± SE. CD, control diet; CDSp, CD with spironolactone; WD, Western diet; WDSp, WD with spironolactone. n = 5–8. †P < 0.05 compared with CD. ‡P < 0.05 compared with WD.

Targeting the MRs Attenuates WD-Induced Systemic and Hepatic Insulin Resistance

We have previously observed that 8 wk of WD promoted systemic insulin resistance in both male and female mice in vivo as measured by hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (20). Consistent with our previous data, both 8 and 16 wk of WD resulted in systemic insulin resistance as evaluated by IPGTT. However, spironolactone only prevented WD-induced impaired glucose tolerance at 16 wk without altering it in 8 wk of WD feeding (Fig. 1, A and B). Furthermore, 16 wk of WD also impaired hepatic insulin metabolic signaling (PI3K/Akt activation), and these abnormalities were prevented by spironolactone administration (Fig. 1, C and D). Moreover, spironolactone increased hepatic Glut4 expression in conjunction with increased PI3K/Akt activation (Fig. 1, D–F).

Figure 1.

Spironolactone prevents WD-induced systemic and hepatic insulin resistance. A and B: eight and 16 wk of WD-induced impaired glucose tolerance that was prevented by spironolactone treatment. C: spironolactone attenuated 16 wk of WD-induced impaired hepatic insulin-induced PI3K/Akt activation as indicated by quantitative analysis. C–F: spironolactone increased Glut 4 expression. E and F: representative images of Glut4 expression in liver with corresponding quantitative analysis. Scale bar = 50 µm; n = 5–8. †P < 0.05 vs. CD. ‡ P < 0.05 vs. WD groups. CD, control diet; WD, Western diet.

Fatty Acid Transporter Proteins Mediate Activated MR-Induced Hepatic Steatosis

Increased FFA levels are related to hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance (21). In this study, 16 wk of WD induced increases in liver weight and FFA levels that were inhibited by spironolactone (Table 2). Meanwhile, WD consumption also increased the hepatic lipid content as determined by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 2, A and B), and this increase in liver fat was associated with increased expression of hepatic fatty acid transporter protein CD36, fatty acid transport proteins (FATP), as well as fatty acid-binding protein-1 (Fabp1) (Fig. 2, C–E). However, WD-induced increases in hepatic fat and associated transporters, CD36 and Fabp1 were prevented by spironolactone, suggesting that CD36 and Fabp1 mediated activated MR-induced hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obesity.

Figure 2.

Spironolactone prevents WD-induced increases in expression of fatty acid transporter proteins and related hepatic lipid content. A and B: spironolactone inhibited 16 wk of WD-induced hepatic lipid accumulation as indicated by corresponding quantitative analysis. Scale bar = 50 µm. Sixteen weeks of WD increased expression of hepatic CD36 (C), FATP (D), and Fabp1 (E). WD-induced increases in expression of CD36 and Fabp1 was inhibited by spironolactone treatment. n = 5 or 6. †P < 0.05 vs. CD. ‡ P < 0.05 vs. WD groups. CD, control diet; Fabp1, fatty acid-binding protein-1; FATP, fatty acid transport proteins; WD, Western diet.

Inhibition of MRs Promote White Adipose Tissue Browning

To determine the role of MRs on adipose tissue differentiation, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance, we evaluated brown fat specific gene expressions (22) including UCP-1, deiodinase 2 (Dio2), β3 adrenergic receptor (Adrb3), PR domain containing 16 (Prdm16) in liver, and visceral fat tissues. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, spironolactone increased hepatic UCP-1 expression that was repressed by 16 wk of WD feeding (Fig. 3, A–D). In epi-abdominal fat tissue, spironolactone also increased white adipose tissue browning characterized by increases in brown fat genes encoding for UCP-1, Dio2, Adrb3, and Prdm16 (Fig. 3, E and F). These data indicate that activated MRs were related to dysregulation of white adipose tissue browning.

Figure 3.

Spironolactone promotes white adipose tissue browning. A and B: spironolactone prevented 16 wk of WD-induced reduction in UCP-1 in liver tissue. C and D: representative images of immunostaining for hepatic UCP-1 and corresponding quantitative analysis. Scale bar = 50 µm. E: spironolactone increased UCP-1 expression in epi-abdominal fat tissue with corresponding quantitative analysis. F: spironolactone increased mRNA levels of UCP-1, Dio2, Adrb3, and Prdm16 in epi-abdominal fat tissue in mice fed a WD. n = 5 or 6. †P < 0.05 vs. CD. ‡ P < 0.05 vs. WD groups. Adrb3, β3 adrenergic receptor; CD, control diet; Dio2, deiodinase 2; Prdm16, PR domain containing 16; UCP-1, uncoupling protein 1; WD, Western diet.

MRs Participate in Hepatic Mitochondria Dysfunction

To elucidate the beneficial effects of the MR antagonist on WD-induced hepatic metabolic disorders and associated mitochondria pathological changes, we further evaluated the hepatic ultrastructure and related gene expressions of uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3), cytochrome b (CYTB), nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator α (PGC1), and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which are involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism (23). Following 16 wk of WD, the lipid droplet content was dramatically increased in liver tissue (Fig. 4A). In addition, WD feeding led to mitochondrial morphology alterations characterized by mitochondrial swelling, decreased matrix density of mitochondrial, and fractures of the outer mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 4A). These pathological changes are associated with reduction of mitochondria encoded genes UCP3, CYTB, NRF1, and PGC1 (Fig. 4B) while not altering the levels of TFAM. These abnormalities were further prevented by spironolactone administration.

Figure 4.

Spironolactone prevents WD-induced hepatic mitochondria (mt) dysfunction. A: representative TEM micrographs depicting hepatic lipid accumulation and mitochondria dysfunction. Scale bar = 0.5 µm. B: effect of spironolactone on the hepatic mRNA levels of UCP3, CYTB, NRF1, PGC1, and TFAM in WD-fed mice as measured by real-time PCR. n = 6. †P < 0.05 vs. CD. ‡P < 0.05 vs. WD groups. CD, control diet; CYTB, cytochrome b; NRF1, nuclear respiratory factor 1; PGC1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator α; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; UCP3, uncoupling protein 3; WD, Western diet.

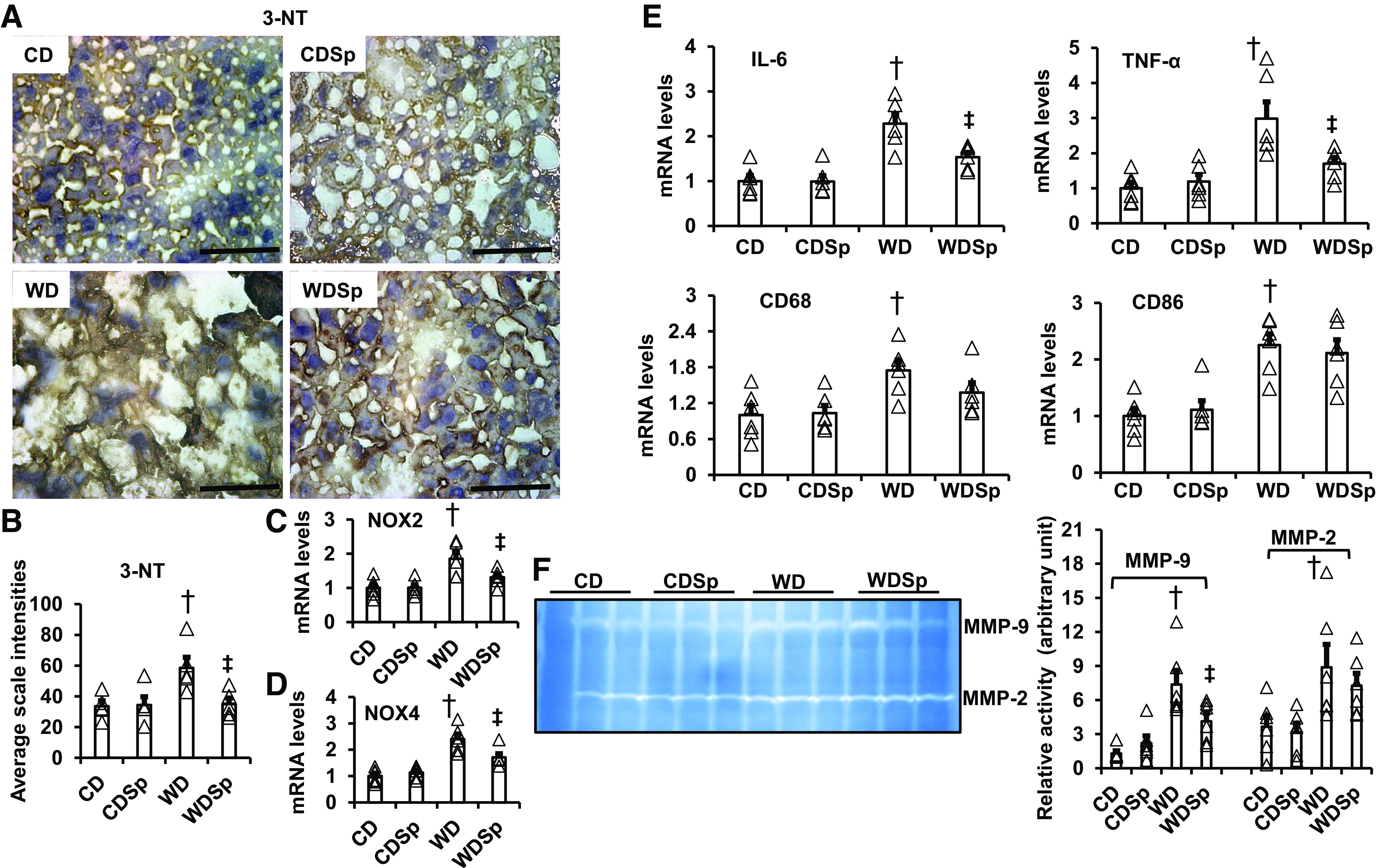

MRs Participate in Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

Our previous studies have shown that WD enhanced tissue oxidative stress in cardiovascular tissues, leading to cardiovascular tissue insulin resistance in conjunction with systemic insulin resistance (10, 24). This study further showed that 16 wk of WD feeding induced an increase of liver 3-NT, which are markers of peroxynitrite formation and excessive tissue oxidative stress (Fig. 5, A and B). Meanwhile, WD consumption also increased the levels of reactive oxygen species generating enzymes NADPH oxidase (Nox) 2 and Nox4. However, spironolactone inhibited 3-NT production, Nox2 and Nox4 expression and thus prevented WD-induced hepatic oxidative stress (Fig. 5, A–D). In addition to increasing hepatic mitochondria dysfunction and oxidative stress, 16 wk consumption of a WD increased hepatic mRNA levels of in interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, CD68 and CD86, as well as hepatic matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 activity (Fig. 5, E and F). Meanwhile, the increased IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression and MMP-9 activity were significantly blunted in spironolactone-treated mice while not altering CD68, CD86, and MMP-2 activity (Fig. 5, E and F). These data suggest MR activation is critical for WD-induced increases in hepatic mitochondria dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

Figure 5.

Spironolactone ameliorates WD-induced hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation. A: representative images of liver sections stained for 3-nitrotyrosine with quantification analysis (B). Scale bar = 50 µm. mRNA expression of Nox2 (C) and Nox4 (D) in liver tissue as measured by real-time PCR. E: WD increased hepatic mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines in IL-6, TNF-α, CD68, and CD86 measured by real-time PCR. F: WD increased hepatic MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity. However, spironolactone inhibited WD induced an increase of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA levels (E), as well as MMP-9 activity (F). n = 4–6. †P < 0.05 vs. CD. ‡P < 0.05 vs. WD groups. CD, control diet; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; Nox, NADPH oxidase; WD, Western diet.

DISCUSSION

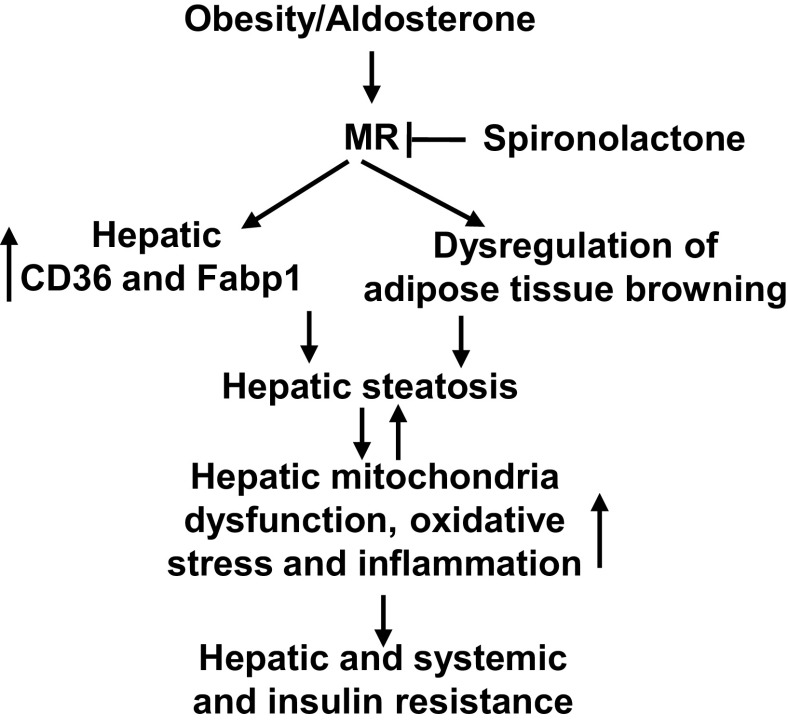

This investigation provides several novel findings that advance our understanding of the role of the MRs in the development of WD-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, including hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress in association with systemic and tissue insulin resistance. First, consumption of a WD for 8- and 16-wk impaired glucose tolerance and induced systemic insulin resistance. Sixteen weeks of WD consumption also induced hepatic tissue insulin resistance characterized by impaired insulin metabolic signaling in PI3K/Akt pathways. Second, the systemic and liver tissue insulin resistance was associated with significant increases in hepatic lipid accumulation and related increases in fatty acid transporter and binding proteins CD36, FATP, and Fabp1. Third, consumption of a WD inhibited mitochondrial metabolic gene expression and induced mitochondria dysfunction. Meanwhile, 16 wk of WD also increased hepatic oxidative stress characterized by increased NOX2, NOX4, and 3-NT with accompanying increasing inflammatory responses. These abnormalities occurring in response to WD feeding were significantly blunted in spironolactone-treated mice. Moreover, inhibition of MRs with spironolactone promoted white adipose tissue browning and hepatic Glut4 expression. These data implicate MR signaling-mediated hepatic steatosis, dysregulation of adipose tissue browning, and related mitochondria dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, as well as systemic and hepatic insulin resistance resulting from diet-induced obesity (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed molecular mechanisms in activated MRs and diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. MRs, mineralocorticoid receptors.

The rationale for having chosen female mice related to the observation that epidemiological data suggest a greater prevalence of obesity in women than in men (25). Furthermore, the elevation in plasma aldosterone levels induced by consumption of a WD is higher in females compared with male mice (7, 20). To this point, increased plasma aldosterone levels have been shown to be associated with insulin resistance as characterized by a reduced ability of insulin to inhibit the production of glucose from the liver and to promote glucose uptake in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in normotensive individuals (4, 26). Moreover, the Framingham Offspring Study also demonstrated an association of increased plasma aldosterone levels with the development of longitudinal increases of cardiometabolic syndrome components, suggesting that aldosterone may play a key role in mediating metabolic risk (27). Indeed, our previous work demonstrated that WD feeding significantly increases plasma aldosterone levels to 3,166 pmol/L levels (7). In the present study, inhibition of MR signaling with spironolactone prevented 16 wk of WD-induced systemic insulin resistance and impaired hepatic insulin metabolic signaling characterized by reduced PI3K/Akt pathways. Meanwhile, our previous data also showed that spironolactone did not affect Glut4 expression in Sprague-Dawley control rats (15). However, the transgenic TG(mRen2)27 rat presented reduced Glut 4 expression that was blunted with in vivo spironolactone treatment (15). Consistent with these data, spironolactone did not significantly affect IPGTT, ex vivo hepatic insulin metallic signaling, Glut4 expression, and hepatic lipid content in the CD C57BL/6J mice. These insignificant discrepancy changes of Glut4 expression and hepatic accumulation in CD C57BL/6J mice may be related to sample size. Furthermore, spironolactone increased hepatic Glut4 expression to promote glucose uptake and maintain glucose hemostasis. To this point, spironolactone prevented high-fat diet-induced development of the cardiometabolic syndrome in obese mice (16), and medical therapy with MR antagonists improves insulin resistance in patients with primary aldosteronism (28).

MR activation is implicated in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which is a condition in which excess fat is stored in liver (17, 29). Our immunostaining data further spironolactone increased hepatic and epi-abdominal fat UCP1 levels in both CD and WD groups, thus spironolactone may prompt white adipose tissue browning in both normal physiological and pathological conditions. Meanwhile, current work showed that spironolactone inhibited WD-induced excess liver lipid accumulation, suggesting that MR activation promotes hepatic steatosis. Moreover, increased lipid deposition was associated with increased expression of hepatic CD36 and Fabp1. Related to this, one study found that protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling pathways were involved in angiotensin II or aldosterone—induced an increase of fatty acid transporter proteins (30). Increased CD36 and Fabp1 promote FFA uptake, transport, oxidation, lipid synthesis, and storage, leading to hepatic fat accumulation and the development of liver steatosis (31, 32). Our data further showed that MR antagonism with spironolactone did reduce hepatic FFA levels. Collectively, these data suggest that enhanced MR activity promotes diet-induced hepatic FFA update, ectopic lipid accumulation, and hepatic steatosis through CD36 and Fabp1.

One of the important findings in this study was that spironolactone did not inhibit the diet-induced increase of fat mass but did induce white adipose tissue browning. Indeed, increased aldosterone levels promote the white adipocyte tissue phenotype (33) by inhibiting UCP1, which is a marker of brown adipose tissue (34). Related to this, one study found that MR antagonists inhibit adipocyte differentiation in both 3T3-L1 cells and primary human adipocytes, and MR knockout mice display defective adipogenesis (35). Consistent with these findings, our data also suggest that reduced MR activity promotes white adipose tissue browning as evidenced by increased expression of UCP-1, Dio2, Adrb3, and Prdm16 in the liver or epi-abdominal fat tissues (22). One recent study also found that inhibition of MR activation reduced hepatic steatosis and inflammation, as well as systemic and tissue insulin resistance in an experimental rodent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease model (36). Another recent study further found that finerenone, a novel nonsteroidal MR antagonism, improves metabolic parameters in high-fat diet-fed mice and activates brown adipose tissue via AMP-activated protein kinase, adipose triglyceride lipase pathway, suggesting that AMP-activated protein kinase activation is essential for finerenone-induced UCP-1 expression in brown adipocytes (37).

The metabolic actions of insulin are dependent on normal mitochondria function, which plays a key role in energy homeostasis by metabolizing nutrients and producing adenosine triphosphate and promoting cellular energy generation (1, 5). Recent data found that a high-fat diet induced the reduction of antioxidants superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, as well as ATP synthase, and complex I and II, leading to mitochondria dysfunction (38). Meanwhile, the current work indicates that WD induced enhanced MR activity and related hepatic steatosis also trigger mitochondrial dysfunction through alteration of mitochondrial respiration, increased fission, and reduced biogenesis in diet-induced obesity (39). Our data further showed that WD consumption impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism and that spironolactone administration increased expression of the mitochondria encoded genes UCP3, CYTB, PGC1, and NRF1 (23). Collectively these data indicate that enhanced MR activity promotes hepatic lipid metabolic disorders and subsequent mitochondria dysfunction in diet-induced obesity.

Mitochondria are also a major source of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and increased ROS are involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (40). Our previous work showed that increased MR activation mediated diet-induced excessive ROS production in renal, artery, and heart (7, 10, 18). Consistent with our previous data, this study also found that MR signaling promoted liver tissue oxidative stress in diet-induced obesity. Moreover, increased ROS generating enzymes, NOX2 and NOX4 are involved in this pathological process. Furthermore, current data suggest that WD induced enhancement of hepatic MR activity mediated excessive ROS-induced increased release of inflammatory cytokines, including IL6, TNFα, and MMP-9. A generally accepted concept is that activated nuclear factor-κB is involved in the inflammation processes. Meanwhile, activated MRs also promote fibrosis, in part, by increasing growth factor-β 1/Smad signaling (41). Therefore, interaction of hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis further aggravate systemic and hepatic insulin resistance.

In summary, the results of this investigation suggest a pivotal role of MR activation in development of systemic and hepatic insulin resistance. This involves increased hepatic steatosis, dysregulation of adipose tissue browning, related mitochondria dysfunction, excessive ROS, and inflammatory response (Fig. 6). There are some limitations to this investigation. For example, we only evaluated one dose of spironolactone. The dose chosen was based on data reported in human studies, and future studies need to address a dose-response of spironolactone in relationship to hepatic and systemic insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity. This study was only conducted in female mice, and future work should include evaluation of MR antagonism on diet-induced impairment of hepatic and system insulin resistance in males as well. These preclinical highly translational data fill a gap in our knowledge of the role of MR signaling in promotion of fatty liver disease, thereby providing a potential therapeutic strategy in the prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in diet-induced obesity.

Perspectives and Significance

This study investigated the role of MRs in diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Enhanced MR signaling following a WD diet induced expression of CD36 and Fabp1, as well as hepatic steatosis. Furthermore, activated MRs also promoted dysregulation of adipose tissue browning. These abnormalities were associated with mitochondria dysfunction, excessive ROS, and inflammatory responses, leading to hepatic and systemic insulin resistance. Importantly, hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver’s mass. Thus, MR activation in hepatocytes may play an important role in diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Other liver cells including hepatic stellate cells, Kupffer cells, and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells may also be involved in this process. Related to this, our previous research showed that activation of endothelial cell MRs is associated with diet-induced tissue oxidative stress and inflammation, which are involved in hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance (10, 24). Therefore, MR activation in other liver cells, including endothelial cells, may have important roles in WD-induced hepatic insulin resistance. Indeed, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzyme 1 (11β-HSD1), expressed in the liver, favors active glucocorticoid formation. Since 11β-HSD2 is not expressed in the liver, endogenous glucocorticoids may also activate hepatic MRs (42). Therefore, we cannot exclude the role of cortisol in MR-mediated hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Accordingly, in vivo acute insulin injection to examine the hepatic insulin resistance may further help elucidate the mechanism by which MRs impair hepatic and systemic insulin metabolic signaling. The specific mechanisms by which diet-induced excessive aldosterone/MR signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance is an area that needs to be further addressed in basic and clinical research.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK124329 and an American Diabetes Association Innovative Basic Science Award 1–17-IBS-201 (to G. Jia). Dr. Sowers received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 HL73101-01A and R01 HL107910-01). Dr. Whaley-Connell received funding from Veterans Affairs Merit System Grant BX003391.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.W.-C., J.R.S., and G.J. conceived and designed research; J.H., D.C., J.L.H., and G.J. performed experiments; J.H., D.C., J.L.H., and G.J. analyzed data; J.H., D.C., A.W.-C., J.R.S., and G.J. interpreted results of experiments; D.C. and G.J. prepared figures; J.R.S. and G.J. drafted manuscript; A.W.-C., J.R.S., and G.J. edited and revised manuscript; A.W.-C., J.R.S., and G.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Scott Rector for help in analyzing data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender SB, McGraw AP, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated vascular insulin resistance: an early contributor to diabetes-related vascular disease? Diabetes 62: 313–319, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li VL, Kim JT, Long JZ. Adipose tissue lipokines: recent progress and future directions. Diabetes 69: 2541–2548, 2020. doi: 10.2337/dbi20-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults with diagnosed diabetes–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53: 1066–1068, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia G, Lockette W, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptors in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and related disorders: from basic studies to clinical disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 320: R276–R286, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00280.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia G, Hill MA, Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ Res 122: 624–638, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodfriend TL, Egan B, Stepniakowski K, Ball DL. Relationships among plasma aldosterone, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and insulin in humans. Hypertension 25: 30–36, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aroor AR, Habibi J, Nistala R, Ramirez-Perez FI, Martinez-Lemus LA, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR, Jia G, Whaley-Connell A. Diet-induced obesity promotes kidney endothelial stiffening and fibrosis dependent on the endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor. Hypertension 73: 849–858, 2019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin N, Wang Y, Liu L, Xue F, Jiang T, Xu M. Dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin system and cardiometabolic status in mice fed a long-term high-fat diet. Med Sci Monit 25: 6605–6614, 2019. doi: 10.12659/MSM.914877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schäfer N, Lohmann C, Winnik S, van Tits LJ, Miranda MX, Vergopoulos A, Ruschitzka F, Nussberger J, Berger S, Lüscher TF, Verrey F, Matter CM. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor activation mediates endothelial dysfunction in diet-induced obesity. Eur Heart J 34: 3515–3524, 2013. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia G, Habibi J, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, DeMarco VG, Ramirez-Perez FI, Sun Z, Hayden MR, Meininger GA, Mueller KB, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor mediates diet-induced aortic stiffness in females. Circ Res 118: 935–943, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabrera D, Rao I, Raasch F, Solis N, Pizarro M, Freire M, Sáenz De Urturi D, Ramírez CA, Triantafilo N, León J, Riquelme A, Barrera F, Baudrand R, Aspichueta P, Arrese M, Arab JP. Mineralocorticoid receptor modulation by dietary sodium influences NAFLD development in mice. Ann Hepatol 24: 100357, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauersachs J, Jaisser F, Toto R. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist treatment in cardiac and renal diseases. Hypertension 65: 257–263, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira JP, Lamiral Z, McMurray JJV, Swedberg K, van Veldhuisen DJ, Vincent J, Rossignol P, Pocock SJ, Pitt B, Zannad F. Impact of insulin treatment on the effect of eplerenone: insights from the EMPHASIS-HF trial. Circ Heart Fail 14: e008075, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.008075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira JP, Zannad F, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Steubl D, Schueler E, Packer M. Interplay of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and empagliflozin in heart failure: EMPEROR-reduced. J Am Coll Cardiol 77: 1397–1407, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lastra G, Whaley-Connell A, Manrique C, Habibi J, Gutweiler AA, Appesh L, Hayden MR, Wei Y, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Low-dose spironolactone reduces reactive oxygen species generation and improves insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle in the TG(mRen2)27 rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E110–E116, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00258.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armani A, Cinti F, Marzolla V, Morgan J, Cranston GA, Antelmi A, Carpinelli G, Canese R, Pagotto U, Quarta C, Malorni W, Matarrese P, Marconi M, Fabbri A, Rosano G, Cinti S, Young MJ, Caprio M. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism induces browning of white adipose tissue through impairment of autophagy and prevents adipocyte dysfunction in high-fat-diet-fed mice. FASEB J 28: 3745–3757, 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-245415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wada T, Kenmochi H, Miyashita Y, Sasaki M, Ojima M, Sasahara M, Koya D, Tsuneki H, Sasaoka T. Spironolactone improves glucose and lipid metabolism by ameliorating hepatic steatosis and inflammation and suppressing enhanced gluconeogenesis induced by high-fat and high-fructose diet. Endocrinology 151: 2040–2049, 2010. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostick B, Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Jia G, Domeier TL, Lambert MD, Aroor AR, Nistala R, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Ma L, Manrique C, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents Western diet-induced diastolic dysfunction in female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1126–H1135, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00898.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeMarco VG, Habibi J, Jia G, Aroor AR, Ramirez-Perez FI, Martinez-Lemus LA, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Sun Z, Meininger GA, Manrique C, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Low-dose mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents Western diet-induced arterial stiffening in female mice. Hypertension 66: 99–107, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manrique C, DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Mugerfeld I, Garro M, Habibi J, Hayden MR, Sowers JR. Obesity and insulin resistance induce early development of diastolic dysfunction in young female mice fed a Western diet. Endocrinology 154: 3632–3642, 2013. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekizkardes H, Chung ST, Chacko S, Haymond MW, Startzell M, Walter M, Walter PJ, Lightbourne M, Brown RJ. Free fatty acid processing diverges in human pathologic insulin resistance conditions. J Clin Invest 130: 3592–3602, 2020. doi: 10.1172/JCI135431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari A, Longo R, Fiorino E, Silva R, Mitro N, Cermenati G, Gilardi F, Desvergne B, Andolfo A, Magagnotti C, Caruso D, Fabiani E, Hiebert SW, Crestani M. HDAC3 is a molecular brake of the metabolic switch supporting white adipose tissue browning. Nat Commun 8: 93, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00182-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heilbronn LK, Gan SK, Turner N, Campbell LV, Chisholm DJ. Markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism are lower in overweight and obese insulin-resistant subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 1467–1473, 2007. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia G, Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Martinez-Lemus LA, Ma L, Whaley-Connell AT, Aroor AR, Domeier TL, Zhu Y, Meininger GA, Mueller KB, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor deletion prevents diet-induced cardiac diastolic dysfunction in females. Hypertension 66: 1159–1167, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 315: 2284–2291, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg R, Hurwitz S, Williams GH, Hopkins PN, Adler GK. Aldosterone production and insulin resistance in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 1986–1990, 2010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingelsson E, Pencina MJ, Tofler GH, Benjamin EJ, Lanier KJ, Jacques PF, Fox CS, Meigs JB, Levy D, Larson MG, Selhub J, D'Agostino RB Sr, Wang TJ, Vasan RS. Multimarker approach to evaluate the incidence of the metabolic syndrome and longitudinal changes in metabolic risk factors: the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation 116: 984–992, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.708537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catena C, Lapenna R, Baroselli S, Nadalini E, Colussi G, Novello M, Favret G, Melis A, Cavarape A, Sechi LA. Insulin sensitivity in patients with primary aldosteronism: a follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 3457–3463, 2006. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang YY, Li C, Yao GF, Du LJ, Liu Y, Zheng XJ, Yan S, Sun JY, Liu Y, Liu MZ, Zhang X, Wei G, Tong W, Chen X, Wu Y, Sun S, Liu S, Ding Q, Yu Y, Yin H, Duan SZ. Deletion of macrophage mineralocorticoid receptor protects hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance through ERα/HGF/Met pathway. Diabetes 66: 1535–1547, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db16-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilon A, Martin G, Bultel-Brienne S, Junquero D, Delhon A, Fruchart JC, Staels B, Clavey V. Regulation of the scavenger receptor BI and the LDL receptor by activators of aldosterone production, angiotensin II and PMA, in the human NCI-H295R adrenocortical cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta 1631: 218–228, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C, Luo X, Chen J, Zhou B, Yang M, Liu R, Liu D, Gu HF, Zhu Z, Zheng H, Li L, Yang G. Osteoprotegerin promotes liver steatosis by targeting the ERK-PPAR-γ-CD36 pathway. Diabetes 68: 1902–1914, 2019. doi: 10.2337/db18-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu YC, Chang CC, Wang CP, Hung WC, Tsai IT, Tang WH, Wu CC, Wei CT, Chung FM, Lee YJ, Hsu CC. Circulating fatty acid-binding protein 1 (FABP1) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Med Sci 17: 182–190, 2020. doi: 10.7150/ijms.40417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zennaro MC, Le Menuet D, Viengchareun S, Walker F, Ricquier D, Lombès M. Hibernoma development in transgenic mice identifies brown adipose tissue as a novel target of aldosterone action. J Clin Invest 101: 1254–1260, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marzolla V, Armani A, Zennaro MC, Cinti F, Mammi C, Fabbri A, Rosano GM, Caprio M. The role of the mineralocorticoid receptor in adipocyte biology and fat metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol 350: 281–288, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caprio M, Antelmi A, Chetrite G, Muscat A, Mammi C, Marzolla V, Fabbri A, Zennaro MC, Fève B. Antiadipogenic effects of the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist drospirenone: potential implications for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology 152: 113–125, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizarro M, Solis N, Quintero P, Barrera F, Cabrera D, Rojas-de Santiago P, Arab JP, Padilla O, Roa JC, Moshage H, Wree A, Inzaugarat E, Feldstein AE, Fardella CE, Baudrand R, Riquelme A, Arrese M. Beneficial effects of mineralocorticoid receptor blockade in experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int 35: 2129–2138, 2015. [Erratum in Liver Int 36: 314, 2016]. doi: 10.1111/liv.12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marzolla V, Feraco A, Gorini S, Mammi C, Marrese C, Mularoni V, Boitani C, Lombes M, Kolkhof P, Ciriolo MR, Armani A, Caprio M. The novel non-steroidal MR antagonist finerenone improves metabolic parameters in high-fat diet-fed mice and activates brown adipose tissue via AMPK-ATGL pathway. FASEB J 34: 12450–12465, 2020. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000164R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang XX, Wang X, Shi TT, Dong JC, Li FJ, Zeng LX, Yang M, Gu W, Li JP, Yu J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the alleviating effect and its mechanism of Polygonatum kingianum. Biomed Pharmacother 117: 109083, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefranc C, Friederich-Persson M, Foufelle F, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Jaisser F. Adipocyte-mineralocorticoid receptor alters mitochondrial quality control leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and senescence of visceral adipose tissue. Int J Mol Sci 22: 2881, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijms22062881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apostolopoulou M, Gordillo R, Koliaki C, Gancheva S, Jelenik T, De Filippo E, Herder C, Markgraf D, Jankowiak F, Esposito I, Schlensak M, Scherer PE, Roden M. Specific hepatic sphingolipids relate to insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetes Care 41: 1235–1243, 2018. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee YA, Friedman SL. Inflammatory and fibrotic mechanisms in NAFLD-Implications for new treatment strategies. J Intern Med 291: 11–31, 2022. doi: 10.1111/joim.13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lloyd-MacGilp SA, Nelson SM, Florin M, Lo M, McKinnell J, Sassard J, Kenyon CJ. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and corticosteroid action in lyon hypertensive rats. Hypertension 34: 1123–1128, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.5.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.