Keywords: antigen presentation, endothelial cells, inflammation, kidney injury, renal

Abstract

Substantial evidence has supported the role of endothelial cell (EC) activation and dysfunction in the development of hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and lupus nephritis (LN). In both humans and experimental models of hypertension, CKD, and LN, ECs become activated and release potent mediators of inflammation including cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species that cause EC dysfunction, tissue damage, and fibrosis. Factors that activate the endothelium include inflammatory cytokines, mechanical stretch, and pathological shear stress. These signals can activate the endothelium to promote upregulation of adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, which promote leukocyte adhesion and migration to the activated endothelium. More importantly, it is now recognized that some of these signals may in turn promote endothelial antigen presentation through major histocompatibility complex II. In this review, we will consider in-depth mechanisms of endothelial activation and the novel mechanism of endothelial antigen presentation. Moreover, we will discuss these proinflammatory events in renal pathologies and consider possible new therapeutic approaches to limit the untoward effects of endothelial inflammation in hypertension, CKD, and LN.

INTRODUCTION

The endothelium is a highly specialized semipermeable single cell layer that lines the circulatory vasculature and lymphatic systems whose total surface area is ∼4,000–7,000 m2 (1). Endothelial cells (ECs) usually have a flat squamous cellular structure of varying thickness depending on their location within the vascular tree. The physiological role of ECs is to provide a physical barrier while maintaining homeostasis, nutrient delivery, and blood flow by the generation and release of nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandins, and endothelin. Importantly, during pathological conditions such as autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome, it has been demonstrated that the endothelium plays a critical role in the inflammatory response by upregulating adhesion molecules, releasing chemokines and cytokines, and increasing permeability and procoagulant activity (1, 2). These inflammatory signaling mechanisms ultimately result in the classical characteristics of endothelial dysfunction. Endothelial dysfunction is a systemic disease state that affects all vascular beds including neural, cardiac, and renal. Clinical measures, including flow-mediated dilation, associate peripheral artery endothelial dysfunction to the systemic condition of the endothelium. Another important role of the endothelium is to recruit, traffic, and home cells of both innate and adaptive immune responses. This review will take a closer look at the pivotal role ECs play in the inception and development of inflammation as a novel innate immune effector and presenter cell in the development of cardiovascular and renal disease states.

IMMUNOLOGICAL RECEPTORS OF THE ENDOTHELIUM

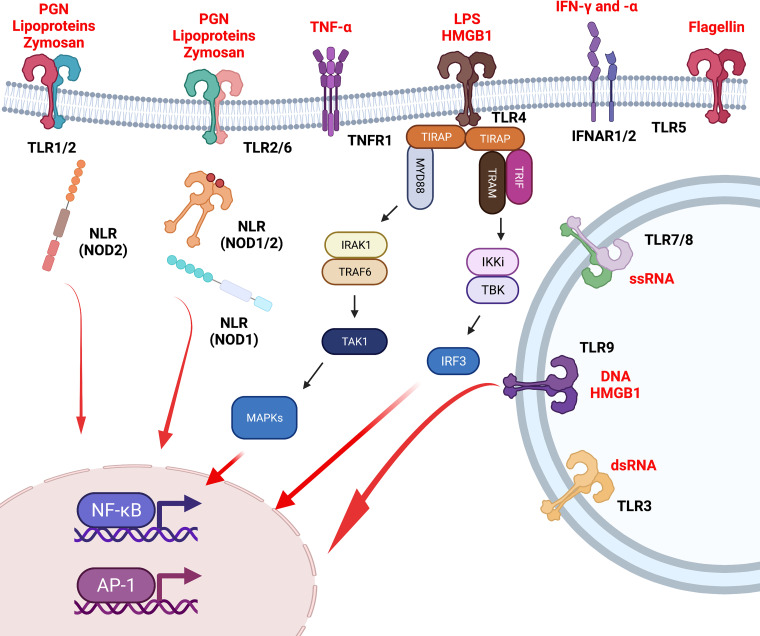

The exquisite orchestration of an effective immune response relies on the interplay of the endothelium and the innate and adaptive immune system. ECs play a vital role in the regulation and inception of an immunological response by providing a physical barrier. They are the first line of sentinel defense against the invasion of pathogens (bacteria, fungi, etc.), pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and damage-associated molecular patterns (3). Therefore, they have developed numerous immunological receptors and pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) (4). NLRs are cytoplasmic receptors that recognize either pathogen-associated molecular patterns or damage-associated molecular patterns, leading to intracellular signaling through the multimeric protein complex known as the inflammasome (5). In contrast, when TLRs are activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns or damage-associated molecular patterns, this leads to the genesis of a signaling cascade through the myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)-dependent pathway. MyD88 functions as an adapter protein, signaling through MAPKs (JNK, ERK, etc.) and inducing activation of the transcription factors NF-κB and activator protein-1 (AP-1) (Fig. 1) (6).

Figure 1.

Immunological receptors of endothelial cells. Endothelial cells express number pattern recognition receptors including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) on the plasma membrane, on the endosomal membrane, and in the cytoplasm. Moreover, endothelial cells express cytokine receptors including interferon receptors (IFNARs) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 (TNFR1). These receptors act as a first line of immunological defense for endothelial cells and subsequent intracellular signaling leads to NF-κB and activator protein (AP)-1 transcription orchestrating endothelial activation and inflammation. Pathological activation of these receptors can lead to endothelial dysfunction, recruitment of immune cells, and the development of end-organ damage in both cardiovascular and renal disease states including hypertension, acute kidney injury, and lupus nephritis.

Numerous studies have reported expression of various TLRs in ECs, including TLR1−TLR4 at high levels and TLR5−TLR10 at lower levels (3, 4). Both TLR2 and TLR4 are upregulated during pathological processes, such as sepsis, and in cardiovascular disease states, including hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and atherosclerosis (7–11). Laminar shear stress applied to coronary artery ECs causes a significant reduction in TLR2 expression (12). Moreover, atherosclerosis-susceptible low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient (LDLR−/−) mice, which lack TLR2, were completely protected from the development of atherosclerosis (13). The authors went on to demonstrate that expression of TLR2 only in bone marrow-derived cells protected these mice from atherosclerosis, suggesting an opposing role of TLR2 signaling in immunological compartments compared with stromal compartments during the development of atherosclerosis. Coronary artery EC TLR4 is upregulated during the formation of coronary atherosclerosis plaques (14). Stimulation of coronary ECs with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a TLR4 ligand, upregulated the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Furthermore, LPS treatment significantly increased leukocyte adhesion molecules intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), demonstrating an activated and inflamed endothelium (15). In animal studies, apolipoprotein E (ApoE)−/− mice susceptible to atherosclerosis, with deficiency in TLR4 or MyD88, had a reduction in the development of atherosclerosis and macrophage recruitment (16). Finally, ECs express TLR3 and TLR9, which are critically important for the recognition of viral RNA and viral and bacterial DNA, respectively (4). Ma et al. (17) demonstrated that inhibition of TLR9 reduced plaque burden and atherosclerotic lesion generation in ApoE−/− mice. Moreover, they demonstrated that inactivation of TLR9 inhibited proinflammatory M1 macrophages and promoted anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages (17). Therefore, these studies demonstrated a vital role of TLR signaling in the proinflammatory phenotype of ECs in cardiovascular disease states, specifically atherosclerosis. In summary, stromal TLR activation and signaling (TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9) promote a proatherogenic response of the endothelium potentiating the development of cardiovascular and renal disease. However, immunological TLRs or more likely cell-specific TLR signaling may be beneficial and/or required for normal immunity and physiological homeostasis.

ROLE IN POTENTIATION OF INFLAMMATION: CYTOKINES, SHEAR STRESS, AND STRETCH

Cytokines

ECs are the first cells to be affected by potent circulating factors including cytokines, chemokines, and hormones. Moreover, ECs have the direct physiological and pathophysiological capability to produce copious amounts of both cytokines and chemokines that promote or suppress an inflammatory cascade. In a seminal study, Randolph et al. (18) demonstrated that the endothelium can be activated by LPS, zymosan, or IL-1β, leading to increased adhesion molecules and conversion of monocytes to activated dendritic cells. Importantly, LPS and zymosan do not play major roles in endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease; however, the cytokines TNF-α and IL- 1, which are derived from activated immune cells in these disease states, potently activate ECs and promote a dysfunctional endothelium (19, 20). Stimulation with TNF-α leads to its binding to the TNF receptor (TNFR), specifically TNFR1, on the EC and subsequent signaling cascades to activate the transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 (20–23). Furthermore, IL-1 binds to the type 1 IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) and signals through the MyD88-dependent pathway to activate NF-κB and AP-1 similarly to TNF-α. After stimulation with either TNF-α or IL-1, ECs upregulate their expression of both adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 to increase adhesiveness for numerous innate and adaptive immune cells (24, 25). Moreover, TNF-α and IL-1 activate ECs to promote the secretion of the cytokines IL-1, IL-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1/chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)2] to potentiate an inflammatory response to recruit and adhere leukocytes to the endothelium (25). Another key cytokine that regulates an inflammatory response in ECs is interferon (IFN)-γ. Treatment of a monolayer of ECs with IFN-γ induces upregulation of ICAM-1 and promotes the transmigration of lymphocytes (20). In keeping with cytokines, it has been recently demonstrated that endothelial transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling drives vascular inflammation and upregulation of numerous proinflammatory genes including ICAM-1 while recruiting CD45+ leukocytes and Ly6G+ cells to the aortic vessel wall (26). The authors went on to demonstrate that endothelial knockout of TGF-β (TGFβiEC-Apoe) in mice promotes the regression of atherosclerotic plaques (26). Secretion of IL-17 by activated T helper 17 cells promotes the development of numerous cardiovascular disease states including hypertension, CKD, and atherosclerosis (27–30). Importantly, stimulation of human aortic ECs (HAECs) with IL-17 promotes proinflammatory ECs by secretion of IL-6, GM-CSF, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)1, and CXCL2, indicating a critical interaction of T cells and the endothelium in promoting a proinflammatory milieu (31). These studies demonstrated that ECs undergo a proinflammatory phenotypic switch in response to cytokines secreted from activated immune cells and help orchestrate tissue inflammation in cardiovascular disease.

Shear Stress

Mechanical forces including shear stress contribute to the anti-inflammatory or proinflammatory phenotypic state of the endothelium. Physiologically, ECs are at a quiescent resting state and express low levels of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1), produce NO, and do not interact with circulating leukocytes (32, 33). Basal production of NO through laminar shear stress suppresses both the production of proinflammatory cytokines and upregulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and P-selectin (34). The master proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α were suppressed during these unidirectional laminar flow conditions, demonstrating an endothelial anti-inflammatory phenotype. Moreover, neutrophil adhesion was significantly reduced under laminar shear stress conditions compared with static flow conditions (34). Laminar shear-dependent production inhibits NF-κB activation in bovine aortic ECs (35). Pathophysiological oscillatory shear stress is seen in disease states such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and CKD. These conditions promote a phenotypic switch of ECs to favor leukocyte adhesion, recruitment, and transmigration to the subendothelial layer to promote tissue inflammation. ECs exposed to oscillatory or irregular flow upregulate adhesion molecules, proinflammatory cytokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induce monocyte adhesion to the endothelium (36). Liu et al. (37) demonstrated that platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1)-dependent ROS-induced NF-κB activation occurs during oscillatory shear stress. Moreover, they demonstrated that oscillatory shear stress induces ROS through a p67phox-dependent mechanism (37). In an elegant study by Xiao et al. (38), oscillatory shear stress of human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) profoundly increased all components of the NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, including procaspase-1, caspase-1, ASC, pro-IL-1β, and active IL-1β compared with pulsatile shear stress. Moreover, they demonstrated that siRNA knockdown of NLRP3 in HUVECs prevented the production of IL-1β in response to oscillatory shear stress, indicating a direct mechanism by which oscillatory shear stress can induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation and the production of IL-1β (Fig. 2) (38). These studies demonstrated that oscillatory shear stress, which is found in clinical disease states such as hypertension and atherosclerosis, drives endothelial activation and inflammation. This mechanism in turn potentiates immune cell activation, inflammation, and end-organ damage in clinical settings.

Figure 2.

Role of physiological stress on activation on endothelial cells. Mechanical mechanisms including oscillatory shear stress and uniaxial hypertensive stretch activate the endothelium to propagate a proinflammatory response. Under normal physiological conditions including laminar shear stress, the endothelium produces large amounts of nitric oxide (NO) and has low expression of adhesion molecules [intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1); left]. During pathological conditions including chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and lupus nephritis, the endothelium becomes activated and upregulates adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and produces copious amount of reactive oxygen species (H2O2 and ) and proinflammatory cytokines. This activated endothelial state promotes leukocyte activation, migration, and adhesion promoting end-organ inflammation and damage in hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus. MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Cyclical Stretch

Another critical mechanical force that is exerted on the endothelium in both normal physiology and pathophysiological conditions is cyclic stretch (39). Under normal physiological cyclic stretch conditions, ECs produce NO and express low levels of adhesion molecules to help regulate vascular blood flow and hemodynamics. Moreover, production of ROS, specifically superoxide () and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is relatively low, contributing to the high NO bioavailability. However, during pathological stretch conditions, as seen during hypertension, arterial stiffening, atherosclerosis, and CKD, ECs become activated and promote a proinflammatory milieu. For instance, HUVECs stretched at 125% or 150% for 24 h had increased secretion of IL-6 compared with nonstretch controls (100%) (40). Moreover, the authors demonstrated that inhibition of translocation of NF-κB by SN50 prevented the increase in IL-6 secretion. Pathological stretch (8% or 15%) significantly increased the production of and inversely decreased NO in HAECs compared with physiological stretch (2%) (40). In this accord, a recent study by Loperena et al. (41) showed that HAECs undergoing hypertensive 10% cyclical stretch (48 h, 1 Hz) significantly increased the secretion of IL-6 and H2O2 and upregulated ICAM-1 compared with control 5% stretch. Hypertensive stretch of ECs promoted the conversion of classical monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) to a proinflammatory intermediate phenotype (CD14+ CD16++) when cocultured with normotensive CD14+ monocytes. Finally, the authors demonstrated that monocytes cocultured with ECs undergoing 10% stretch potently drove both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation, indicating a critical role of the endothelium to promote both innate and adaptive immune responses (41). Ten percent stretch of HAECs significantly increased both mRNA expression and protein expression of ICAM-1 compared with 5% stretch alone in an in vitro model of hypertension (41). Taken together, these studies demonstrated that cytokines and mechanical forces activate the endothelium to promote the activation of ECs through adhesion molecules and ROS. These mechanisms in turn promote inflammation and the recruitment of leukocytes during pathological disease states (Fig. 2). Conditions such as hypertension stretch or oscillatory shear stress prime the endothelium to promote immune cell adhesion, diapedesis, and activation promoting vascular and end-organ inflammation. These two pathophysiological conditions have been shown to play a critical role in the development of hypertensive kidney injury, atherosclerosis, and aortic stiffening. However, the precise signaling mechanisms of these pathophysiological stimuli on the activation of immune cells need to be further investigated in renal and cardiovascular pathologies.

NOVEL ANTIGEN-PRESENTING CELLS

In the field of cardiovascular and renal immunology, the focus has mostly been on the interactions of the innate immune system in presentation of antigens to promote the development of cardiovascular disease states. Although ECs are not classified as true professional antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages), they have the rare capability to express both major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I and MHC II and process antigen for presentation through these molecules (2, 42, 43). Importantly, the only known function of MHC I and MHC II is to present antigen to T cells for an antigen-mediated response. The presentation of antigens by ECs was first described in human ECs lining microvessels by in situ hybridization (43, 44). It was first described in the normal renal microvasculature by Muczynski et al. (45), who demonstrated that HLA-DR, but not HLA-DP or HLA-DQ, was expressed by immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis. Moreover, ECs have been demonstrated to express costimulatory molecules including CD80, CD86, inducible costimulator ligand, program death-1 ligand 1, and program death-1 ligand 1, which is a critical step in the activation of T cells (46–49). Although there are some reports showing that both CD80 and CD86, which interact with CD28 on the T cell, are present on ECs (50–52), there have been other reports that have not found these critical costimulatory molecules in ECs (49, 51). However, there is interesting evidence that EC-mediated antigen presentation occurs during chronic inflammation. For instance, human ECs stimulated with IFN-γ increased expression of MHC II molecules and activated both CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells. In contrast, MHC II expression by human ECs by stimulation of IFN-γ does not activate naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. It has been demonstrated that CXCL10 and physiological shear stress of HUVECs recruit and capture effector memory CD4+ T cells in response to TNF stimulation (53). Moreover, Pober et al. (54) went on to further demonstrate in a subsequent study that effector memory CD4+ T cells are recruited by ECs through MHC II antigen presentation in T cell receptor-driven transendothelial migration, indicating a specific role of MHC II presentation by the endothelium (Fig. 3). In a recent study, Van Beusecum et al. (55) demonstrated that HAECs undergoing hypertensive stretch (10% stretch) significantly increased expression of HLA-DR compared with HAECs undergoing 5% normotensive stretch by flow cytometric analysis. With this fundamental groundwork studied in vitro and in transplantation studies, this is clearly an area of investigation in the fields of cardiovascular and renal pathologies including CKD, lupus nephritis (LN), and hypertension where EC antigen presentation is unknown.

Figure 3.

Endothelial cells as novel antigen-presenting cells. Multiple inflammatory stimulation by interferon (IFN)-γ or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α promotes endothelial inflammation. These stimuli promote upregulation of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II. Upregulation of MHC II has been demonstrated to activate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells along with adequate costimulation through molecules such as CD80, CD86, and inducible costimulator ligand. This critical signaling pathway could play a novel and critical role in the development of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and various autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. IFNR, IFN receptor; PDL, program death-1 ligand; TCR, T cell receptor.

ENDOTHELIAL INFLAMMATION IN RENAL DISEASE STATES

Acute Kidney Injury

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined as an abrupt loss of renal blood flow or kidney function. Every year, more than 13.3 million cases of AKI occur around the world. AKI is strongly associated with patient long-term mortality, along with the development of CKD. The role of the endothelium in the pathogenesis of AKI has been well demonstrated (56). For instance, after ischemia-reperfusion injury, there is upregulated ICAM-1, P-selectin, and E-selectin on ECs in response to injury (57–59). Within hours of reperfusion, adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium of peritubular capillaries occurs resulting in the production of chemokines to promote macrophage infiltration (60). Of critical importance in the recruitment of macrophages in AKI, ECs secrete fractalkine [chemokine (C-3X-C motif) ligand 1 (CX3CL1)] to home macrophages to the site of renal injury (Fig. 4) (61). In addition, Kirita et al. (62) performed single cell RNA sequencing on mouse kidneys after AKI and found that ECs play a predominate role in secretion of CCL2 in the acute phase of AKI (4−12 h). This study demonstrated at a single cell level that the endothelium initiates the pathway for leukocyte migration, adhesion, and diapedesis in AKI. There have been numerous therapies driven toward reducing EC and leukocyte interactions by specifically inhibiting adhesion molecules on the endothelium during AKI. Bojakowski et al. (63) demonstrated that inhibition of P-selectin with fucoidan, a P-selectin inhibitor, significantly increased renal blood flow following ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat model, which may have renal protective benefits. In a seminal study, Kelly et al. (59) demonstrated that genetic deletion of ICAM-1 (ICAM-1−/−) in mice prevented AKI as measured by creatinine, histology, survival, and immune cell infiltration compared with wild-type mice. Furthermore, anti-ICAM-1 antibody treatment protected wild-type mice from AKI. Clinically, pretreatment with ICAM-1 antibody in human subjects prevented delayed graft rejection, indicating ICAM-1 monoclonal antibody treatment as a potential disease changing therapy for AKI (64, 65). Finally, Satoh et al. (66) demonstrated that glomerular ECs significantly upregulate critical costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 after 3 days in a rat model of ischemia-reperfusion injury. These studies suggest that the renal endothelium plays a critical role in the potentiation of inflammation in the pathological development of both experimental and clinical AKI.

Figure 4.

Endothelial inflammation and activation in renal disease states. Endothelial activation, dysfunction, and inflammation comprise a complex orchestration of numerous cell types, adhesion molecules, and cytokines/chemokines that play a critical role in the development of numerous renal pathological disease states. In acute kidney injury (AKI; top left), the endothelium secretes chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 (CX3CL1), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1) to promote macrophage, monocyte, and neutrophil homing. Moreover, upregulation of adhesion molecules [intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and P-selectin] promotes rolling, adhesion, and diapedesis of immune cells to the subendothelial layer to promote vascular and organ inflammation. In lupus nephritis (top right), there is an increase in autoantibody production that can lead to the binding of endothelial cells (ECs). The endothelium secretes proinflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and IL-18] and chemokines [monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)] to promote immune cell activation and homing to the site of EC injury. Moreover, there is a decrease in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production promoting a proinflammatory and prooxidant status at the environment of the endothelium. Immune cells, including monocytes and neutrophils, home to the subendothelial layer and promote tissue inflammation. Finally, there is an upregulation in membrane-bound adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) and soluble adhesion molecules (sICAM-1). In diabetic nephropathy (bottom left), the endothelium secretes copious amounts of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, and IL-1 to promote monocyte, macrophage, and neutrophil activation. Moreover, the endothelium produces ROS, upregulates adhesion molecules [ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule-1 (ELAM-1], secretes key chemokines to promote adhesion and diapedesis of immune cells into the surrounding tissue. Finally, in coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19; bottom right), there is circulating severe acute respiratory virus-related coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus that binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the endothelium. This in turn upregulates ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and vascular adhesion protein (VAP-1) to promote immune cell adhesion. Macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils transmigrate to the subendothelium and promote vasculitis and vascular dysfunction. Finally, as cells undergo cell death, endothelial Toll-like receptor activation promotes cytokine production and further inflammation in a feedforward mechanism.

In sepsis-induced AKI, the reduction in glomerular blood flow can be attributed to the reduction in NO synthase in ECs. Sepsis is a life-threatening loss of organ function caused by a dysregulated immune response from the subject. The annual incidence of sepsis is ∼48.9 million people worldwide (67). There have been numerous animal and human studies investigating the role of EC activation and inflammation in models of sepsis. It has been demonstrated that P-selectin and E-selectin are the first adhesion molecules upregulated in models of endotoxemia (68, 69). For instance, mice exposed to LPS significantly increased neutrophil accumulation in the glomeruli, peritubular capillaries, and postvenule capillaries (70, 71). Repeated exposure of LPS in mice significantly increased expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in mesangial and glomerular ECs associated with increased leukocyte and neutrophil accumulation in the tubulointerstitial region (Fig. 4) (72). In another model of sepsis, cecal ligation and puncture increased rolling and adhesion of neutrophils in cortical postcapillary venules as early as 4 h after the procedure (73). In a seminal study, Matsukawa et al. (74) demonstrated that mice lacking E-selectin and P-selectin are protected from sepsis-induced renal injury, through a reduction in CXCL1. Clinically, EC activation and inflammation have been demonstrated in sepsis-induced AKI in patients. For instance, elevated plasma levels of the soluble forms of adhesion molecules PECAM-1, E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 are associated with increased disease severity (75–77). Moreover, analysis of postmortem biopsies demonstrated a vast elevation in monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils in glomeruli and microvascular segments, (78), indicating a clear clinical role of ECs and immune cell cross talk in AKI development and progression. Understanding the complex signaling mechanism by which ECs and the immune system orchestrate end-organ damage in AKI is critical for future clinical therapies.

Diabetic Nephropathy

A major microvascular complication of diabetes is diabetic nephropathy leading to CKD and end-stage renal failure. Both immune cells and inflammatory cytokines play a critical role in the development of diabetic nephropathy. Urinary levels of IL-18, IL-6, and IL-8 are increased in patients with diabetic nephropathy (79). Furthermore, both TNF-α and IL-1, the critical regulators of endothelial activation, are increased in these patients. In experimental models of diabetic nephropathy, renal expression of IL-1 increases in parallel to adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule-1 (Fig. 4) (80). Elevated soluble levels of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are associated with the progression of microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria in diabetic nephropathy (81, 82). This could be due to altered glomerular hemodynamics and/or increased EC permeability. Importantly, activated glomerular capillary ECs secreted the potent chemokines CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and CCL5, which are both upregulated in diabetes, to promote macrophage infiltration and diapedesis (83). Clinically, numerous therapies reduce inflammatory mediators in diabetic nephropathy, but Na+-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors have enormous direct beneficial effects on endothelial activation and inflammation. In vitro, cotreatment with canagliflozin on IL-1-stimulated human ECs prevents the adhesion of monocytic cells (U937 cells) and secretion of MCP-1 (84). Moreover, dapagliflozin prevented the increase in ICAM-1 and adhesion of human leukocytes to human ECs, demonstrating a direct therapeutic effect on endothelial inflammation. Finally, Li et al. (85) demonstrated that empagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and canagliflozin all prevented EC permeability and endothelium-derived ROS production in response to 10% cyclic stretch. However, Na+-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition did not alter the secretion of IL-6 or IL-8 from 10% stretched ECs (85). These studies demonstrated that therapies targeting endothelial inflammation and activation could provide vast benefits to patients with diabetic nephropathy.

Lupus Nephritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by autoantibody formation and subsequent immune complex deposition into target tissues. LN is one of the most severe complications of SLE, with ∼22% of patients developing end-stage renal disease (86). Renal involvement in SLE is due to a multitude of factors, including immune complex deposition into the subendothelium (87) and binding of autoantibodies directly to ECs (88, 89), resulting in the production of proinflammatory cytokines (90) and upregulation of cellular adhesion molecules (91–93). This leads to the recruitment and activation of circulating immune cells while increasing permeability of the endothelium, with consequent immune cell infiltration of the glomeruli and kidney damage (94). Endothelial impairment in LN is associated with the formation of necrotic and crescentic glomerular lesions (95). Renal biopsy tissues from patients with LN stained for CD34 reveal impaired capillary regeneration and a loss of ECs that contribute to the development of fibrous crescents (96). Moreover, markers of endothelial dysfunction (pentraxin 3, VCAM-1, MCP-1, and von Willebrand factor) are increased in plasma, serum, and/or urine from patients with lupus compared with healthy controls (97–101).

In SLE and LN, there is an imbalance between EC repair and injury, which has been shown to be triggered by type I IFNs (102–104). This imbalance is evidenced by an increase in circulating apoptotic ECs along with decreases in bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells and circulating myeloid angiogenic cells in patients with SLE and LN (104–106). High numbers of circulating apoptotic ECs correlate with endothelial dysfunction, which is indicative of future atherosclerosis development (106, 107). Thus, endothelial damage in LN is apparent not only in the kidneys but also systemically. Patients with SLE are found to have increased thickness of carotid arteries along with endothelial dysfunction as assessed by flow-mediated dilation (108). A meta-analysis by Lu et al. (109) suggested that the risk of cardiovascular disease was tripled in patients with SLE compared with the general population and that the incidence of hypertension was also increased. In addition, patients with LN were at heightened risk for cardiovascular disease compared with patients with SLE (109).

The endothelial surface is the first site where circulating immune cells interact with local tissues. Glomerular ECs are coated with a network of membrane-bound proteoglycans and glycoproteins called the glycocalyx. One of the components of the glycocalyx is hyaluronic acid, a ligand of the CD44 receptor (110). CD44 is highly expressed on activated T cells. Kadoya et al. (111) used spontaneous models of murine lupus to provide evidence that activated memory T cells preferentially home to glomerular capillaries by binding their CD44 to hyaluronic acid within the endothelial glycocalyx. This escalation in homing of activated memory T cells coincided with increased hyaluronic acid content and increased thickness of the glomerular endothelial glycocalyx, which was found to be 3.5 times thicker in LN models than that of healthy control mice. Their study implicated the homing of activated memory T cells along with changes in the glomerular endothelial glycocalyx as a potential novel mechanism driving LN disease progression. Another study by Liu et al. (112) found that tripartite motif-containing 27, which is involved in the inflammatory response, was highly expressed in glomerular ECs from patients with LN. Downregulation of tripartite motif-containing 27 prevented EC injury and loss of the glycocalyx. These two studies suggested that the role of the glomerular endothelial glycocalyx in LN encompasses both pathogenic and protective mechanisms, where a delicate balance must be maintained to prevent immune cell homing and inflammation along with maintenance of the endothelial barrier.

In the proliferative form of LN, deposits of immune complexes deposit into or are formed in situ in renal microvessels, which modulate the endothelial microenvironment, altering immune cell interaction with the endothelium and compromising its integrity. A study by Bergtold et al. (113) demonstrated that immune complex deposition into the subendothelium may activate circulating myeloid cells that express Fc receptors, allowing them to infiltrate glomeruli. Olaru et al. (94) further revealed that intracapillary immune complexes could recruit and activate CD16+ slan-expressing monocytes to perpetuate feedforward proinflammatory responses in the glomerular endothelium (Fig. 4). The role of circulating inflammatory cells in LN was further revealed in a study by Kuriakose et al. (114) demonstrating that TLR-activated patrolling monocytes mediate vascular inflammation and kidney injury during the early phases of lupus-like glomerulonephritis.

Glomerular ECs are important proinflammatory contributors to LN. Dimou et al. (115) discovered that conditionally immortalized human glomerular ECs treated with serum from juvenile patients with LN had enhanced IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expression. Russell et al. (116) found that human renal glomerular ECs stimulated with SLE and LN serum secreted platelet-derived growth factor-BB, IL-8, and IL-15, which positively correlated with neutrophil chemotaxis. They further revealed that SLE and LN serum-treated human renal glomerular ECs promoted greater neutrophil chemotaxis than serum from healthy controls, particularly during disease activity (116). Their studies demonstrated that glomerular ECs play an active role in the inflammatory response in SLE and LN and that unique factors in serum may induce these responses.

Diminished NO bioavailability and dysfunctional endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) play an important role in LN EC physiology. Biopsies from patients with severe LN have reduced expression of eNOS in glomerular ECs (117). Buie et al. (118) demonstrated that SLE serum reduced NO production in HUVECs and that cotreatment with L-sepiapterin (a precursor to tetrahydrobiopterin, which restores eNOS function) enhanced HUVEC capacity to produce NO. In another study, Buie et al. (119) showed that SLE serum produced an IFN-α gene signature in HUVECs and that stimulation with IFN-α repressed eNOS expression and NO production, along with upregulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. The exact pathophysiology of LN is yet to be fully understood, but it is evident that perturbations of the vascular endothelium play a critical role in disease progression.

COVID-19

Among the most prevalent comorbidities noted in patients confirmed with complicated coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) infection are hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and cerebrovascular disease (120, 121). Over the past 2 years, numerous studies have demonstrated that severe acute respiratory virus-related coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) uses angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2 as a point of entry into cells using the spike protein. ACE2 has been detected in numerous cell types including both arterial and venous ECs and the endothelium in the interlobular arteries within the kidney (122, 123). Escher et al. (124) were the first to demonstrate that COVID-19 infection is associated with EC activation and dysfunction. Although numerous seminal studies have been conducted and reviews written about COVID-19 and ECs, we will only highlight some findings. In patients infected with COVID-19, it has been found that plasma levels of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, CX3CL5, vascular adhesion protein-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor are increased (Fig. 4) (124, 125). Moreover, in pediatric patients, post-COVID syndrome presenting with Kawasaki vasculitis has been observed, demonstrating a possible pivotal role of the endothelium in this pathology (126, 127). Postmortem biopsies have demonstrated vascular endotheliitis in patients who have been diagnosed with COVID-19 (128, 129). Moreover, as cells undergo cell death, damage-associated molecular patterns could activate pattern recognition receptors, specifically TLRs on the endothelium, leading to activation and cell injury and propagating endothelial dysfunction (130). As aforementioned, endothelial dysfunction, activation, and inflammation play an essential role in the development of numerous renal pathologies. Persistent chronic endothelial dysfunction in patients, such as hypertension, diabetes, or LN, may present a vulnerable condition that predisposes patients to more severe complications with COVID-19.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

One common feature of chronic inflammatory diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and systemic autoimmune disease is endothelial dysfunction. An example of this lies in SLE, where patients display EC dysfunction by flow-mediated dilation that is enhanced with them having LN. It might be postulated that this endothelial dysfunction is simply a product rather than mediator of pathology in these diseases. However, several lines of evidence suggest that ECs are active innate immune effector cells that respond to the environment of each chronic inflammatory disease to play an active role in promoting inflammation. One of the challenges in studying the direct role of ECs in modulating or promoting inflammatory responses in vivo stems from the difficulty of directly targeting ECs with therapeutics.

It is recognized that chronic systemic inflammation from hypertension, LN, and CKD plays a critical role in the development of end-organ damage in patients. However, targeting endothelial inflammation specifically has yet to be tested and demonstrates a clear need for future clinical investigation. A plethora of clinical evidence implicates endothelial activation and inflammation in these disease states (65–69). The use of statins, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers has been demonstrated to improve endothelial dysfunction, yet none of the known treatments directly target endothelial inflammation. The potential future use and discovery of endothelium-specific targeted immunomodulatory therapies could provide beneficial treatments for this shared common feature of endothelial activation and inflammation in hypertension, CKD, diabetes, and LN. Therefore, further investigation of these novel pathways in vitro and in vivo is needed to address the clinically important effects of endothelial inflammatory responses in these disease states.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Grants CXC001248 (to J.C.O.) and 1K2BX005605-01 (to J.P.V.B.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.L.R. and J.P.V.B. prepared figures; J.C.O., D.L.R., and J.P.V.B. drafted manuscript; J.C.O., D.L.R., and J.P.V.B. edited and revised manuscript; J.C.O., D.L.R., and J.P.V.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Figures were created with BioRender.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sumpio BE, Riley JT, Dardik A. Cells in focus: endothelial cell. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 34: 1508–1512, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goncharov NV, Popova PI, Avdonin PP, Kudryavtsev IV, Serebryakova MK, Korf EA, Avdonin PV. Markers of endothelial cells in normal and pathological conditions. Biochem (Mosc) Suppl Ser A Membr Cell Biol 14: 167–183, 2020. doi: 10.1134/S1990747819030140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvador B, Arranz A, Francisco S, Córdoba L, Punzón C, Llamas MÁ, Fresno M. Modulation of endothelial function by Toll like receptors. Pharmacol Res 108: 46–56, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khakpour S, Wilhelmsen K, Hellman J. Vascular endothelial cell Toll-like receptor pathways in sepsis. Innate Immun 21: 827–846, 2015. doi: 10.1177/1753425915606525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opitz B, Eitel J, Meixenberger K, Suttorp N. Role of Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors and RIG-I-like receptors in endothelial cells and systemic infections. Thromb Haemost 102: 1103–1109, 2009. doi: 10.1160/TH09-05-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol 16: 3–9, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Beusecum JP, Zhang S, Cook AK, Inscho EW. Acute toll-like receptor 4 activation impairs rat renal microvascular autoregulatory behaviour. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 221: 204–220, 2017. doi: 10.1111/apha.12899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh MV, Cicha MZ, Nunez S, Meyerholz DK, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy are differentially mediated by TLR3- and TLR4-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 316: H1027–H1038, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00697.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roshan MH, Tambo A, Pace NP. The role of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Int J Inflam 2016: 1532832, 2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/1532832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bomfim GF, Dos Santos RA, Oliveira MA, Giachini FR, Akamine EH, Tostes RC, Fortes ZB, Webb RC, Carvalho MH. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to blood pressure regulation and vascular contraction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 122: 535–543, 2012. doi: 10.1042/CS20110523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salomão R, Martins PS, Brunialti MKC, Fernandes Mda L, Martos LSW, Mendes ME, Gomes NE, Rigato O. TLR signaling pathway in patients with sepsis. Shock 30, Suppl 1: 73–77, 2008. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318181af2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunzendorfer S, Lee HK, Tobias PS. Flow-dependent regulation of endothelial Toll-like receptor 2 expression through inhibition of SP1 activity. Circ Res 95: 684–691, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000143900.19798.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullick AE, Soldau K, Kiosses WB, Bell TA 3rd, Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Increased endothelial expression of Toll-like receptor 2 at sites of disturbed blood flow exacerbates early atherogenic events. J Exp Med 205: 373–383, 2008. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edfeldt K, Swedenborg J, Hansson GK, Yan ZQ. Expression of toll-like receptors in human atherosclerotic lesions: a possible pathway for plaque activation. Circulation 105: 1158–1161, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeuke S, Ulmer AJ, Kusumoto S, Katus HA, Heine H. TLR4-mediated inflammatory activation of human coronary artery endothelial cells by LPS. Cardiovasc Res 56: 126–134, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michelsen KS, Wong MH, Shah PK, Zhang W, Yano J, Doherty TM, Akira S, Rajavashisth TB, Arditi M. Lack of Toll-like receptor 4 or myeloid differentiation factor 88 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10679–10684, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403249101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma C, Ouyang Q, Huang Z, Chen X, Lin Y, Hu W, Lin L. Toll-like receptor 9 inactivation alleviated atherosclerotic progression and inhibited macrophage polarized to M1 phenotype in ApoE−/− mice. Dis Markers 2015: 909572, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/909572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science 282: 480–483, 1998. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bevilacqua MP, Pober JS, Majeau GR, Cotran RS, Gimbrone MA Jr.. Interleukin 1 (IL-1) induces biosynthesis and cell surface expression of procoagulant activity in human vascular endothelial cells. J Exp Med 160: 618–623, 1984. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pober JS, Gimbrone MA Jr, Lapierre LA, Mendrick DL, Fiers W, Rothlein R, Springer TA. Overlapping patterns of activation of human endothelial cells by interleukin 1, tumor necrosis factor, and immune interferon. J Immunol 137: 1893–1896, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slowik MR, De Luca LG, Fiers W, Pober JS. Tumor necrosis factor activates human endothelial cells through the p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor but the p75 receptor contributes to activation at low tumor necrosis factor concentration. Am J Pathol 143: 1724–1730, 1993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loetscher H, Stueber D, Banner D, Mackay F, Lesslauer W. Human tumor necrosis factor α (TNF α) mutants with exclusive specificity for the 55-kDa or 75-kDa TNF receptors. J Biol Chem 268: 26350–26357, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackay F, Loetscher H, Stueber D, Gehr G, Lesslauer W. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-induced cell adhesion to human endothelial cells is under dominant control of one TNF receptor type, TNF-R55. J Exp Med 177: 1277–1286, 1993. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munro JM, Pober JS, Cotran RS. Tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma induce distinct patterns of endothelial activation and associated leukocyte accumulation in skin of Papio anubis. Am J Pathol 135: 121–133, 1989. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun RL, Huang CX, Bao JL, Jiang JY, Zhang B, Zhou SX, Cai WB, Wang H, Wang JF, Zhang YL. CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) suppresses high density lipoprotein (HDL) internalization and cholesterol efflux via CC-chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) induction and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 291: 19532–19544, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.714279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen PY, Qin L, Li G, Wang Z, Dahlman JE, Malagon-Lopez J, Gujja S, Cilfone NA, Kauffman KJ, Sun L, Sun H, Zhang X, Aryal B, Canfran-Duque A, Liu R, Kusters P, Sehgal A, Jiao Y, Anderson DG, Gulcher J, Fernandez-Hernando C, Lutgens E, Schwartz MA, Pober JS, Chittenden TW, Tellides G, Simons M. Endothelial TGF-β signalling drives vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Nat Metab 1: 912–926, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0102-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norlander AE, Saleh MA, Kamat NV, Ko B, Gnecco J, Zhu L, Dale BL, Iwakura Y, Hoover RS, McDonough AA, Madhur MS. Interleukin-17A regulates renal sodium transporters and renal injury in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 68: 167–174, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 55: 500–507, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavoz C, Matus YS, Orejudo M, Carpio JD, Droguett A, Egido J, Mezzano S, Ruiz-Ortega M. Interleukin-17A blockade reduces albuminuria and kidney injury in an accelerated model of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 95: 1418–1432, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allam G, Abdel-Moneim A, Gaber AM. The pleiotropic role of interleukin-17 in atherosclerosis. Biomed Pharmacother 106: 1412–1418, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mai J, Nanayakkara G, Lopez-Pastrana J, Li X, Li YF, Wang X, Song A, Virtue A, Shao Y, Shan H, Liu F, Autieri MV, Kunapuli SP, Iwakura Y, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang XF. Interleukin-17A promotes aortic endothelial cell activation via transcriptionally and post-translationally activating p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. J Biol Chem 291: 4939–4954, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.690081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Traub O, Berk BC. Laminar shear stress: mechanisms by which endothelial cells transduce an atheroprotective force. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 677–685, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzales RS, Wick TM. Hemodynamic modulation of monocytic cell adherence to vascular endothelium. Ann Biomed Eng 24: 382–393, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF02660887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luu NT, Rahman M, Stone PC, Rainger GE, Nash GB. Responses of endothelial cells from different vessels to inflammatory cytokines and shear stress: evidence for the pliability of endothelial phenotype. J Vasc Res 47: 451–461, 2010. doi: 10.1159/000302613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yurdagul A Jr, Chen J, Funk SD, Albert P, Kevil CG, Orr AW. Altered nitric oxide production mediates matrix-specific PAK2 and NF-κB activation by flow. Mol Biol Cell 24: 398–408, 2013. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNally JS, Davis ME, Giddens DP, Saha A, Hwang J, Dikalov S, Jo H, Harrison DG. Role of xanthine oxidoreductase and NAD(P)H oxidase in endothelial superoxide production in response to oscillatory shear stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2290–H2297, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Collins C, Kiosses WB, Murray AM, Joshi M, Shepherd TR, Fuentes EJ, Tzima E. A novel pathway spatiotemporally activates Rac1 and redox signaling in response to fluid shear stress. J Cell Biol 201: 863–873, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201207115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao H, Lu M, Lin TY, Chen Z, Chen G, Wang WC, Marin T, Shentu TP, Wen L, Gongol B, Sun W, Liang X, Chen J, Huang HD, Pedra JH, Johnson DA, Shyy JY. Sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelium mediates hemodynamic-induced atherosclerosis susceptibility. Circulation 128: 632–642, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jufri NF, Mohamedali A, Avolio A, Baker MS. Mechanical stretch: physiological and pathological implications for human vascular endothelial cells. Vasc Cell 7: 8, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13221-015-0033-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi S, Nagino M, Komatsu S, Naruse K, Nimura Y, Nakanishi M, Sokabe M. Stretch-induced IL-6 secretion from endothelial cells requires NF-κB activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308: 306–312, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loperena R, Van Beusecum JP, Itani HA, Engel N, Laroumanie F, Xiao L, Elijovich F, Laffer CL, Gnecco JS, Noonan J, Maffia P, Jasiewicz-Honkisz B, Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Mikolajczyk T, Sliwa T, Dikalov S, Weyand CM, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Hypertension and increased endothelial mechanical stretch promote monocyte differentiation and activation: roles of STAT3, interleukin 6 and hydrogen peroxide. Cardiovasc Res 114: 1547–1563, 2018. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bosse D, George V, Candal FJ, Lawley TJ, Ades EW. Antigen presentation by a continuous human microvascular endothelial cell line, HMEC-1, to human T cells. Pathobiology 61: 236–238, 1993. doi: 10.1159/000163800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hancock WW, Kraft N, Atkins RC. The immunohistochemical demonstration of major histocompatibility antigens in the human kidney using monoclonal antibodies. Pathology 14: 409–414, 1982. doi: 10.3109/00313028209092120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hart DN, Fuggle SV, Williams KA, Fabre JW, Ting A, Morris PJ. Localization of HLA-ABC and DR antigens in human kidney. Transplantation 31: 428–433, 1981. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muczynski KA, Cotner T, Anderson SK. Unusual expression of human lymphocyte antigen class II in normal renal microvascular endothelium. Kidney Int 59: 488–497, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khayyamian S, Hutloff A, Büchner K, Gräfe M, Henn V, Kroczek RA, Mages HW. ICOS-ligand, expressed on human endothelial cells, costimulates Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion by memory CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 6198–6203, 2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092576699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodig N, Ryan T, Allen JA, Pang H, Grabie N, Chernova T, Greenfield EA, Liang SC, Sharpe AH, Lichtman AH, Freeman GJ. Endothelial expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 down-regulates CD8+ T cell activation and cytolysis. Eur J Immunol 33: 3117–3126, 2003. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grabie N, Gotsman I, DaCosta R, Pang H, Stavrakis G, Butte MJ, Keir ME, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Lichtman AH. Endothelial programmed death-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) regulates CD8+ T-cell mediated injury in the heart. Circulation 116: 2062–2071, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.709360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Epperson DE, Pober JS. Antigen-presenting function of human endothelial cells. Direct activation of resting CD8 T cells. J Immunol 153: 5402–5412, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lozanoska-Ochser B, Klein NJ, Huang GC, Alvarez RA, Peakman M. Expression of CD86 on human islet endothelial cells facilitates T cell adhesion and migration. J Immunol 181: 6109–6116, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray AG, Khodedoust MM, Pober JS, Bothwell ALM. Porcine aortic endothelial cells activate human T cells: direct presentation of MHC antigens and costimulation by ligands for human CD2 and CD28. Immunity 1: 57–63, 1994. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seino K, Azuma M, Bashuda H, Fukao K, Yagita H, Okumura K. CD86 (B70/B7-2) on endothelial cells co-stimulates allogeneic CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol 7: 1331–1337, 1995. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.8.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manes TD, Pober JS. Identification of endothelial cell junctional proteins and lymphocyte receptors involved in transendothelial migration of human effector memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 186: 1763–1768, 2011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manes TD, Pober JS. Antigen presentation by human microvascular endothelial cells triggers ICAM-1-dependent transendothelial protrusion by, and fractalkine-dependent transendothelial migration of, effector memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 180: 8386–8392, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Beusecum JP, Barbaro NR, Smart CD, Patrick DM, Loperena R, Zhao S, de la Visitacion N, Ao M, Xiao L, Shibao CA, Harrison DG. Growth arrest specific-6 and axl coordinate inflammation and hypertension. Circ Res 129: 975–991, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Basile DP. The endothelial cell in ischemic acute kidney injury: implications for acute and chronic function. Kidney Int 72: 151–156, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Molitoris BA, Sandoval R, Sutton TA. Endothelial injury and dysfunction in ischemic acute renal failure. Crit Care Med 30: S235–S240, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly KJ, Williams WW Jr, Colvin RB, Bonventre JV. Antibody to intercellular adhesion molecule 1 protects the kidney against ischemic injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 812–816, 1994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly KJ, Williams WW Jr, Colvin RB, Meehan SM, Springer TA, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Bonventre JV. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice are protected against ischemic renal injury. J Clin Invest 97: 1056–1063, 1996. doi: 10.1172/JCI118498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelly KJ, Sutton TA, Weathered N, Ray N, Caldwell EJ, Plotkin Z, Dagher PC. Minocycline inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in a rat model of ischemic renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F760–F766, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00050.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu LH, Oh DJ, Dursun B, He Z, Hoke TS, Faubel S, Edelstein CL. Increased macrophage infiltration and fractalkine expression in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324: 111–117, 2008. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kirita Y, Wu H, Uchimura K, Wilson PC, Humphreys BD. Cell profiling of mouse acute kidney injury reveals conserved cellular responses to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 15874–15883, 2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005477117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bojakowski K, Abramczyk P, Bojakowska M, Zwolińska A, Przybylski J, Gaciong Z. Fucoidan improves the renal blood flow in the early stage of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. J Physiol Pharmacol 52: 137–143, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haug CE, Colvin RB, Delmonico FL, Auchincloss H Jr, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Preffer FI, Rothlein R, Norris S, Scharschmidt L, Cosimi AB. A phase I trial of immunosuppression with anti-ICAM-1 (CD54) mAb in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 55: 766–772, 1993. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salmela K, Wramner L, Ekberg H, Hauser I, Bentdal O, Lins LE, Isoniemi H, Backman L, Persson N, Neumayer HH, Jørgensen PF, Spieker C, Hendry B, Nicholls A, Kirste G, Hasche G. A randomized multicenter trial of the anti-ICAM-1 monoclonal antibody (enlimomab) for the prevention of acute rejection and delayed onset of graft function in cadaveric renal transplantation: a report of the European Anti-ICAM-1 Renal Transplant Study Group. Transplantation 67: 729–736, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Satoh S, Suzuki A, Asari Y, Sato M, Kojima N, Sato T, Tsuchiya N, Sato K, Senoo H, Kato T. Glomerular endothelium exhibits enhanced expression of costimulatory adhesion molecules, CD80 and CD86, by warm ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Lab Invest 82: 1209–1217, 2002. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000029620.13097.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer S, Fleischmann-Struzek C, Machado FR, Reinhart KK, Rowan K, Seymour CW, Watson RS, West TE, Marinho F, Hay SI, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Angus DC, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 395: 200–211, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coughlan AF, Hau H, Dunlop LC, Berndt MC, Hancock WW. P-selectin and platelet-activating factor mediate initial endotoxin-induced neutropenia. J Exp Med 179: 329–334, 1994. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fries JW, Williams AJ, Atkins RC, Newman W, Lipscomb MF, Collins T. Expression of VCAM-1 and E-selectin in an in vivo model of endothelial activation. Am J Pathol 143: 725–737, 1993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cunningham PN, Wang Y, Guo R, He G, Quigg RJ. Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in endotoxin-induced acute renal failure. J Immunol 172: 2629–2635, 2004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jongman RM, Zwiers PJ, van de Sluis B, van der Laan M, Moser J, Zijlstra JG, Dekker D, Huijkman N, Moorlag HE, Popa ER, Molema G, van Meurs M. Partial deletion of Tie2 affects microvascular endothelial responses to critical illness in a vascular bed and organ-specific way. Shock 51: 757–769, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baran D, Vendeville B, Ogborn M, Katz N, Rubin E, Nguyen V. Cell adhesion molecule expression in murine lupus-like nephritis induced by lipopolysaccharide. Nephron 84: 167–176, 2000. doi: 10.1159/000045565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herter JM, Rossaint J, Spieker T, Zarbock A. Adhesion molecules involved in neutrophil recruitment during sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. J Innate Immun 6: 597–606, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000358238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matsukawa A, Lukacs NW, Hogaboam CM, Knibbs RN, Bullard DC, Kunkel SL, Stoolman LM. Mice genetically lacking endothelial selectins are resistant to the lethality in septic peritonitis. Exp Mol Pathol 72: 68–76, 2002. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2001.2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Skibsted S, Jones AE, Puskarich MA, Arnold R, Sherwin R, Trzeciak S, Schuetz P, Aird WC, Shapiro NI. Biomarkers of endothelial cell activation in early sepsis. Shock 39: 427–432, 2013. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182903f0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kjaergaard AG, Dige A, Nielsen JS, Tønnesen E, Krog J. The use of the soluble adhesion molecules sE-selectin, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, sPECAM-1 and their ligands CD11a and CD49d as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in septic and critically ill non-septic ICU patients. APMIS 124: 846–855, 2016. doi: 10.1111/apm.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu WK, McNeil JB, Wickersham NE, Shaver CM, Bastarache JA, Ware LB. Vascular endothelial cadherin shedding is more severe in sepsis patients with severe acute kidney injury. Crit Care 23: 18, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2315-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lerolle N, Nochy D, Guerot E, Bruneval P, Fagon JY, Diehl JL, Hill G. Histopathology of septic shock induced acute kidney injury: apoptosis and leukocytic infiltration. Intensive Care Med 36: 471–478, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1723-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Donate-Correa J, Ferri CM, Sánchez-Quintana F, Pérez-Castro A, González-Luis A, Martín-Núñez E, Mora-Fernández C, Navarro-González JF. Inflammatory cytokines in diabetic kidney disease: pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications. Front Med (Lausanne) 7: 628289, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.628289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Altannavch TS, Roubalová K, Kucera P, Andel M. Effect of high glucose concentrations on expression of ELAM-1, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in HUVEC with and without cytokine activation. Physiol Res 53: 77–82, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clausen P, Jacobsen P, Rossing K, Jensen JS, Parving HH, Feldt-Rasmussen B. Plasma concentrations of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 are elevated in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus with microalbuminuria and overt nephropathy. Diabet Med 17: 644–649, 2000. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Güler S, Cakir B, Demirbas B, Yönem A, Odabasi E, Onde U, Aykut O, Gürsoy G. Plasma soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 levels are increased in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Horm Res 58: 67–70, 2002. doi: 10.1159/000064664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kikuchi Y, Ikee R, Hemmi N, Hyodo N, Saigusa T, Namikoshi T, Yamada M, Suzuki S, Miura S. Fractalkine and its receptor, CX3CR1, upregulation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic kidneys. Nephron Exp Nephrol 97: e17–e25, 2004. doi: 10.1159/000077594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mancini SJ, Boyd D, Katwan OJ, Strembitska A, Almabrouk TA, Kennedy S, Palmer TM, Salt IP. Canagliflozin inhibits interleukin-1 β -stimulated cytokine and chemokine secretion in vascular endothelial cells by AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Sci Rep 8: 5276, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23420-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li X, R ömer G, Kerindongo RP, Hermanides J, Albrecht M, Hollmann MW, Zuurbier CJ, Preckel B, Weber NC. Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors ameliorate endothelium barrier dysfunction induced by cyclic stretch through inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Int J Mol Sci 22: 6044, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijms22116044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tektonidou MG, Dasgupta A, Ward MM. Risk of end-stage renal disease in patients with lupus nephritis, 1971–2015: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheumatol 68: 1432–1441, 2016. doi: 10.1002/art.39594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Agnello V, Koffler D, Kunkel HG. Immune complex systems in the nephritis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Kidney Int 3: 90–99, 1973. doi: 10.1038/ki.1973.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.D'Cruz DP, Houssiau FA, Ramirez G, Baguley E, McCutcheon J, Vianna J, Haga HJ, Swana GT, Khamashta MA, Taylor JC, Davies DR, Hughes GRV. Antibodies to endothelial cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: a potential marker for nephritis and vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol 85: 254–261, 1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kondo A, Takahashi K, Mizuno T, Kato A, Hirano D, Yamamoto N, Hayashi H, Koide S, Takahashi H, Hasegawa M, Hiki Y, Yoshida S, Miura K, Yuzawa Y. The level of IgA antibodies to endothelial cells correlates with histological evidence of disease activity in patients with lupus nephritis. PLoS One 11: e0163085, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Calvani N, Richards HB, Tucci M, Pannarale G, Silvestris F. Up-regulation of IL-18 and predominance of a Th1 immune response is a hallmark of lupus nephritis. Clin Exp Immunol 138: 171–178, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.da Rosa Franchi Santos LF, Stadtlober NP, Costa Dall'Aqua LG, Scavuzzi BM, Guimarães PM, Flauzino T, Batisti Lozovoy MA, Mayumi Iriyoda TV, Vissoci Reiche EM, Dichi I, Maes M, Colado Simão A. Increased adhesion molecule levels in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationships with severity of illness, autoimmunity, metabolic syndrome and cortisol levels. Lupus 27: 380–388, 2018. doi: 10.1177/0961203317723716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sabry A, Sheashaa H, El-Husseini A, El-Dahshan K, Abdel-Rahim M, Elbasyouni SR. Intercellular adhesion molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with lupus nephritis. Clin Rheumatol 26: 1819–1823, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0580-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wuthrich RP. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression in murine lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 42: 903–914, 1992. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Olaru F, Döbel T, Lonsdorf AS, Oehrl S, Maas M, Enk AH, Schmitz M, Gröne EF, Gröne HJ, Schäkel K. Intracapillary immune complexes recruit and activate slan-expressing CD16+ monocytes in human lupus nephritis. JCI Insight 31: e96492, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.96492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gilkeson GS, Mashmoushi AK, Ruiz P, Caza TN, Perl A, Oates JC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase reduces crescentic and necrotic glomerular lesions, reactive oxygen production, and MCP1 production in murine lupus nephritis. PLoS One 8: e64650, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fujita E, Nagahama K, Shimizu A, Aoki M, Higo S, Yasuda F, Mii A, Fukui M, Kaneko T, Tsuruoka S. Glomerular capillary and endothelial cell injury is associated with the formation of necrotizing and crescentic lesions in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Nippon Med Sch 82: 27–35, 2015. doi: 10.1272/jnms.82.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cieślik P, Hrycek A. Pentraxin 3 as a biomarker of local inflammatory response to vascular injury in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity 48: 242–250, 2015. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2014.983264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu KY, Yung S, Chau MK, Tang CS, Yap DY, Tang AH, Ying SK, Lee CK, Chan TM. Clinico-pathological associations of serum VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 levels in patients with lupus nephritis. Lupus 30: 1039–1050, 2021. doi: 10.1177/09612033211004727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Davies JC, Carlsson E, Midgley A, Smith EMD, Bruce IN, Beresford MW, Hedrich CM; BILAG-BR and MRC MASTERPLANS Consortia. A panel of urinary proteins predicts active lupus nephritis and response to rituximab treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 60: 3747–3759, 2021. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abozaid MA, Ahmed GH, Tawfik NM, Sayed SK, Ghandour AM, Madkour RA. Serum and urine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 as a markers for lupus nephritis. Egypt J Immunol 27: 97–107, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tan Y, Luan ZQ, Hao JB, Song D, Yu F, Zhao MH. Plasma ADAMTS-13 activity in proliferative lupus nephritis: a large cohort study from China. Lupus 27: 389–398, 2018. doi: 10.1177/0961203317723715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee PY, Li Y, Richards HB, Chan FS, Zhuang H, Narain S, Butfiloski EJ, Sobel ES, Reeves WH, Segal MS. Type I interferon as a novel risk factor for endothelial progenitor cell depletion and endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 56: 3759–3769, 2007. doi: 10.1002/art.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thacker SG, Berthier CC, Mattinzoli D, Rastaldi MP, Kretzler M, Kaplan MJ. The detrimental effects of IFN-α on vasculogenesis in lupus are mediated by repression of IL-1 pathways: potential role in atherogenesis and renal vascular rarefaction. J Immunol 185: 4457–4469, 2010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, Somers EC, Dodick T, Barrat FJ, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. Interferon-α promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood 110: 2907–2915, 2007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yao G, Liu ZH, Zheng C, Zhang X, Chen H, Zeng C, Li LS. Evaluation of renal vascular lesions using circulating endothelial cells in patients with lupus nephritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47: 432–436, 2007. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rajagopalan S, Somers EC, Brook RD, Kehrer C, Pfenninger D, Lewis E, Chakrabarti A, Richardson BC, Shelden E, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. Endothelial cell apoptosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a common pathway for abnormal vascular function and thrombosis propensity. Blood 103: 3677–3683, 2004. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Hunter LM, Watkins MT, Nedeljkovic ZS, Menzoian JO, Vita JA. Predictive value of noninvasively determined endothelial dysfunction for long-term cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 1769–1775, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mikołajczyk TP, Osmenda G, Batko B, Wilk G, Krezelok M, Skiba D, Sliwa T, Pryjma JR, Guzik TJ. Heterogeneity of peripheral blood monocytes, endothelial dysfunction and subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 25: 18–27, 2016. doi: 10.1177/0961203315598014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lu X, Wang Y, Zhang J, Pu D, Hu N, Luo J, An Q, He L. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus face a high risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol 94: 107466, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Aruffo A, Stamenkovic I, Melnick M, Underhill CB, Seed B. CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate. Cell 61: 1303–1313, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90694-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kadoya H, Yu N, Schiessl IM, Riquier-Brison A, Gyarmati G, Desposito D, Kidokoro K, Butler MJ, Jacob CO, Peti-Peterdi J. Essential role and therapeutic targeting of the glomerular endothelial glycocalyx in lupus nephritis. JCI Insight 5: e131252, 2020. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu J, Xu J, Huang J, Gu C, Liu Q, Zhang W, Gao F, Tian Y, Miao X, Zhu Z, Jia B, Tian Y, Wu L, Zhao H, Feng X, Liu S. TRIM27 contributes to glomerular endothelial cell injury in lupus nephritis by mediating the FoxO1 signaling pathway. Lab Invest 101: 983–997, 2021. [Erratum in Lab Invest 101: 1110, 2021]. doi: 10.1038/s41374-021-00591-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bergtold A, Gavhane A, D'Agati V, Madaio M, Clynes R. FcR-bearing myeloid cells are responsible for triggering murine lupus nephritis. J Immunol 177: 7287–7295, 2006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kuriakose J, Redecke V, Guy C, Zhou J, Wu R, Ippagunta SK, Tillman H, Walker PD, Vogel P, Hacker H. Patrolling monocytes promote the pathogenesis of early lupus-like glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest 129: 2251–2265, 2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI125116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dimou P, Wright RD, Budge KL, Midgley A, Satchell SC, Peak M, Beresford MW. The human glomerular endothelial cells are potent pro-inflammatory contributors in an in vitro model of lupus nephritis. Sci Rep 9: 8348, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44868-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Russell DA, Markiewicz M, Oates JC. Lupus serum induces inflammatory interaction with neutrophils in human glomerular endothelial cells. Lupus Sci Med 7: e000418, 2020. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2020-000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Furusu A, Miyazaki M, Abe K, Tsukasaki S, Shioshita K, Sasaki O, Miyazaki K, Ozono Y, Koji T, Harada T, Sakai H, Kohno S. Expression of endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase in human glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 53: 1760–1768, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jones Buie JN, Pleasant Jenkins D, Muise-Helmericks R, Oates JC. L-sepiapterin restores SLE serum-induced markers of endothelial function in endothelial cells. Lupus Sci Med 6: e000294, 2019. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2018-000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Buie JJ, Renaud LL, Muise-Helmericks R, Oates JC. IFN-α negatively regulates the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide production: implications for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 199: 1979–1988, 2017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 8: 475–481, 2020. [Erratum in Lancet Respir Med 8: e26, 2020]. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, Akdis CA, Gao YD. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan. Allergy 75: 1730–1741, 2020. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lely AT, Hamming I, van Goor H, Navis GJ. Renal ACE2 expression in human kidney disease. J Pathol 204: 587–593, 2004. doi: 10.1002/path.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 203: 631–637, 2004. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Escher R, Breakey N, Lämmle B. Severe COVID-19 infection associated with endothelial activation. Thromb Res 190: 62, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tong M, Jiang Y, Xia D, Xiong Y, Zheng Q, Chen F, Zou L, Xiao W, Zhu Y. Elevated expression of serum endothelial cell adhesion molecules in COVID-19 patients. J Infect Dis 222: 894–898, 2020. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]