Abstract

In recent years, fibroblast activation protein (FAP) has emerged as an attractive target for the diagnosis and radiotherapy of cancers using FAP-specific radioligands. Herein, we aimed to design a novel 18F-labeled FAP tracer ([18F]AlF-P-FAPI) for FAP imaging and evaluated its potential for clinical application. The [18F]AlF-P-FAPI novel tracer was prepared in an automated manner within 42 min with a non-decay corrected radiochemical yield of 32 ± 6% (n = 8). Among A549-FAP cells, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI demonstrated specific uptake, rapid internalization, and low cellular efflux. Compared to the patent tracer [18F]FAPI-42, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI exhibited lower levels of cellular efflux in the A549-FAP cells and higher stability in vivo. Micro-PET imaging in the A549-FAP tumor model indicated higher specific tumor uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI (7.0 ± 1.0% ID/g) compared to patent tracers [18F]FAPI-42 (3.2 ± 0.6% ID/g) and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 (2.7 ± 0.5% ID/g). Furthermore, in an initial diagnostic application in a patient with nasopharyngeal cancer, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FDG PET/CT showed comparable results for both primary tumors and lymph node metastases. These results suggest that [18F]AlF-P-FAPI can be conveniently prepared, with promising characteristics in the preclinical evaluation. The feasibility of FAP imaging was demonstrated using PET studies.

KEY WORDS: Fibroblast activation protein, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, PET, Nasopharyngeal cancer

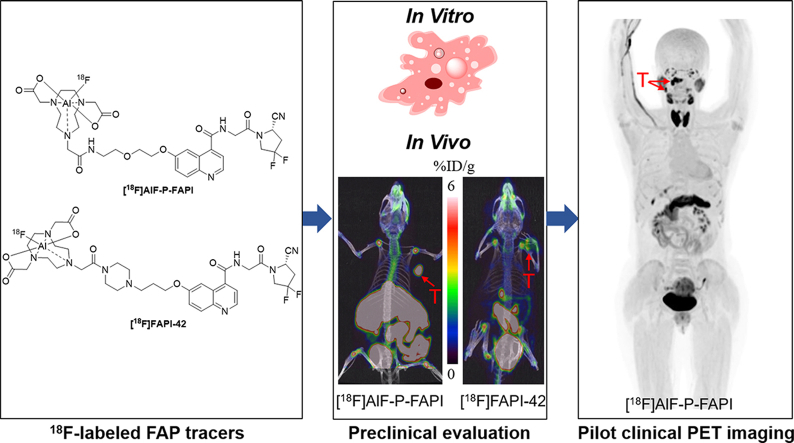

Graphical abstract

A novel 18F-labeled FAP tracer ([18F]AlF-P-FAPI) was developed and directly compared in vitro and in vivo characteristics with [18F]FAPI-42. Furthermore, a pilot study of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was performed in a patient.

1. Introduction

Fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a type II transmembrane serine protease, exhibits post-proline dipeptidyl peptidase and endopeptidase activity1. Under physiological conditions, FAP is expressed at negligible or non-detectable levels in most normal adult tissues, except for multipotent bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) and alpha cells of Langerhans islets2. However, FAP is highly upregulated in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in greater than 90% of epithelial tumors and in the extracellular matrix of the tumor microenvironment3,4. It has been established that FAP levels are related to the survival and prognosis in cancer patients, indicating that they have a vital role in cancer development1,5,6. Therefore, FAP has become a promising target for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Recently, several positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers for FAP were successfully developed and imaged in vivo7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 (Fig. 1). Among these, the 68Ga-labeled ligands have been extensively studied and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 has been applied in clinical imaging for various cancers9, 10, 11,14, 15, 16, 17, 18. However, 68Ga-labeled tracers have a relatively short half-life of 68Ga (t1/2 = 67.7 min, 88.9% β+), and are limited in the availability of radionuclide from 68Ge/68Ga-generators. In contrast, 18F (t1/2 = 109.8 min, 96.7% β+) is the most widely-used radionuclide in PET, can be produced in larger doses by one cyclotron production, and can be delivered over longer distances. Hence, there is a strong demand for 18F-labeled FAP targeting tracers. Thus far, several 18F-labeled FAP-targeting radiotracers have been reported7,8. Giesel et al.8 reported using a 18F-labeled FAP tracer, [18F]FAPI-74, for the imaging of lung cancer patients in a clinical setting; however, the preclinical data is not yet available. Another tracer, [18F]FGlc-FAPI, was reported based on [18F]fluoroglycosylation for FAP imaging by Toms et al.7. However, the excretion of [18F]FGlc-FAPI was through the kidneys and hepatobiliary pathway in a preclinical study, which might be a problem for use in the clinical study. Therefore, efforts are underway to develop novel 18F-labeled FAP tracers to achieve higher tumor uptake using a straightforward method.

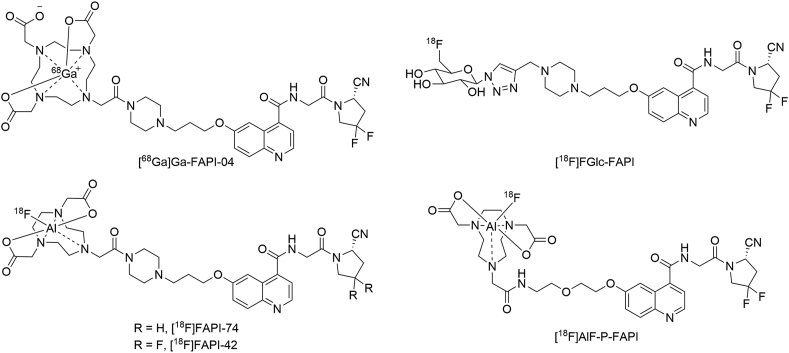

Figure 1.

The structures of [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04, [18F]FGlc-FAPI, [18F]FAPI-74, [18F]FAPI-42, and [18F]AlF-P-FAPI.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been widely used for extending the in vivo half-life of various drugs19,20. In this study, we introduced a PEG linker between the chelator NOTA (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid) and the pharmacophore FAP inhibitor to prepare an imaging probe ([18F]AlF-P-FAPI) via Al18F-chelation. Additionally, we directly compared the in vitro and in vivo characteristics of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI with two patent tracers, [18F]FAPI-42 and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-0411,21. Lastly, we used [18F]AlF-P-FAPI to perform a pilot study in a patient with cancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemistry

All the reagents and solvents were purchased commercially, were of analytical grade, and were used without further purification. DOTA-FAPI-04 was obtained from Nanchang TanzhenBio Co., Ltd. (Nanchang, China) with high chemical purity (>95%). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data were acquired using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). The synthesis of non-radioactive compounds, including the reference compounds [19F]AlF-P-FAPI and [19F]FAPI-42, and their precursors, are described in detail in Supporting Information Schemes S1 and S2.

2.2. Radiochemistry and quality control

No-carrier-added [18F]fluoride was synthesized using an 18-MeV proton bombardment of a high-pressure [18O]H2O target utilizing a General Electric PET trace biomedical cyclotron (PET 800; GE, USA). Sep-Pak Plus QMA and Sep-Pak C18-Light cartridges were purchased from Waters Associates. Radioactivity was quantified through the use of a Capintec CAPRAC-R dose calibrator (NJ, USA).

18F-labeled FAP tracers labeling via Al18F-chelation were produced on a modified AllInOne synthesis module (Trasis, Ans, Belgium), as reported previously8,22,23. After production in a cyclotron, [18F]F− was transferred into the module and trapped on a Sep-Pak Plus QMA, preconditioned with 5 mL of 0.5 mol/L sodium acetate buffer at pH = 3.9 and 10 mL of water. Subsequently, [18F]F− (37‒74 GBq) was eluted using 0.35 mL of 0.5 mol/L sodium acetate buffer pH = 3.9 to a mixture of AlCl3 (40.0 nmol, 20.0 μL, 2.0 mmol/L in 0.2 mol/L sodium acetate buffer pH = 4.0) and precursor (NOTA-P-FAPI or NOTA-FAPI-42; 80.0 nmol) in 300 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After being heated for 15 min at 105 °C, the mixture was then cooled and diluted with 5 mL of water. Next, the diluted solution was transferred over an activated C18 cartridge, preconditioned with 5 mL of ethanol (EtOH) and 10 mL of water. Afterwards, the cartridge was washed with 20 mL of water and flushed with nitrogen sequentially. The desired radiolabeled compound was eluted from the C18 cartridge with 1 mL of ethanol/water (1/1, v/v), and the C18 cartridge was flushed with 10 mL of 0.9% NaCl. The eluate was passed through a sterile Millipore filter (0.22 μm) into a sterile vial. The final drug product solution was evaluated through a quality control, described in more detail in the Supporting Information.

2.3. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding assays

The experiments were performed using PlexAray HT (Plexera Bioscience, Seattle, WA, USA). The FAP ligands (10 mmol/L in ddH2O) were prepared in 384 wells and spotted on 3D photocrosslinked (PCL) chip in a UV-free room with 45% humidity. The obtained PCL chips were then dried in a vacuum chamber to evaporate the solvent, and the chips were irradiated for 15 min using a 365-nm UV cross-linker instrument (UVJLY-1; Beijing BINTA Instrument Technology Company). The irradiated energy on the surface then amounted to 2.8 J/cm2. After undergoing UV treatment, the chips were rinsed in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), EtOH, and ddH2O for 15 min each. Finally, the chips were dried under nitrogen gas for further use. An SPR imaging instrument (Kx5; Plexera) was used to monitor the whole procedure in real-time to quantify the interaction between immobilized biomolecules and flowing proteins. In brief, a chip with well-prepared biomolecular microarrays was assembled using a plastic flow cell for sample loading. The optical architecture and operation details of the PlexArray HT were previously described elsewhere24. The protein sample was then prepared at the appropriate concentration in PBS running buffer while a 10 mmol/L glycine-HCl buffer (pH = 2.0) was used as a regeneration buffer. A typical binding curve was acquired using a flowing protein sample at 2 μL/s for a 300-s association, followed by a flowing running buffer for 300-s dissociation, and followed by a 200-s regeneration buffer at 3 μL/s. To obtain the results for binding affinity, seven gradient concentrations of the flowing phase (2000, 1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.3 nmol/L, protein sample) were prepared and flowed, respectively. All the binding signals were converted to standard refractive units (RU) by calibrating every spot with 1% glycerol (w/v) in a running buffer with a known refractive index change (1200 RU). Binding data were collected and evaluated using a commercial SPR imaging analysis software (Plexera SPR Data Analysis Model; Plexera).

2.4. Partition coefficient

The n-octanol/PBS partition coefficients of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, [18F]FAPI-42, and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 were determined, as previously described25.

2.5. Cell lines

The human cell lines A549 (ATCC, USA) were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum, Gibco, USA) and 1% streptomycin and penicillin (Gibco, USA) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The A549-FAP cell line, which stably expressed human FAP, was acquired using lentiviral infection, following a two-week screening process with 2 μg of puromycin (Thermo Fisher, USA).

2.6. Cell studies and animal models

The detailed protocols for in vitro cell studies and animal experiments, including cell uptake, efflux, internalization, and tumor transplantation, are provided in the Supporting Information. All animal studies were carried out and granted approval according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University.

2.7. In vitro and in vivo stability

Detailed procedures for in vitro and in vivo stability of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 are included in the Supporting Information.

2.8. Micro-PET imaging

For dynamic micro-PET imaging studies, either 18F- or 68Ga-labeled tracer (5.55–11.1 MBq, n = 3) were injected through the lateral tail vein into mice bearing A549-FAP tumor xenograft using an Inveon Micro-PET/CT scanner (Siemens; Erlangen, Germany). Image studies were conducted using a three-dimensional ordered-subset expectation maximum (OSEM) algorithm (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). A549-FAP tumor-bearing mice were co-injected for the blocking study using DOTA-FAPI-04 (100 nmol/mouse, n = 3) as a competitor. The images and regions of interest (ROIs) were produced using Inevon Research Workplace 4.1 software (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

2.9. Biodistribution studies

Organ distribution studies were carried out using mice with xenografted A549-FAP tumors with and without DOTA-FAPI-04 (100 nmol/mouse, n = 4). The mice were then injected through the tail vein using [18F]AlF-P-FAPI (1.11–1.85 MBq) and euthanized 1 h after injection. Organs of interest and tumor were quickly dissected and weighed, and radioactivity was quantified using of a γ-counter and calculated as the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g).

2.10. PET/CT imaging and analysis

The PET/CT imaging study was performed on a total-body PET/CT scanner (uEXPLORER, United Imaging Healthcare; Shanghai, China) and granted approval by the Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital (No. NFEC-2020-205), registered at chictr001@chictr.org.cn (ChiCTR2100045757) and was conducted according to the latest guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. These were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient signed an informed consent form before participating in the study. A 41-year-old patient with nasopharyngeal cancer was examined using 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose ([18F]FDG) and [18F]AlF-P-FAPI on two consecutive days. The patient received an intravenous injection of [18F]FDG (3.7 MBq/kg) while fasting for at least 6 h on the first day and [18F]AlF-P-FAPI (3.7 MBq/kg) on the second day without fasting. One hour after the injection of [18F]FDG or [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, the patient underwent imaging and PET images were reconstructed using ordered subsets expectation-maximization algorithm (2 iterations, 10 subsets, 192 × 192 matrix) and corrected for CT-based attenuation, dead time, random events, and scatter26.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data were reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and significance of comparison between the two data sets was determined using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Significance was defined at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Chemistry and radiochemistry

The labeling precursors (NOTA-P-FAPI and NOTA-FAPI-42) and reference compounds ([19F]AlF-P-FAPI and [19F]FAPI-42) were successfully prepared with high chemical purity (>95%) and identified through the use of mass spectrometry (Supporting Information).

18F-labeled FAP tracers ([18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42) were successfully prepared in an automated manner via Al18F-chelation on the AllInOne module. The total synthesis time was 40 ± 2 min, starting from the end of [18F]F− transfer to the synthesis module to obtain the final product. The non-decay corrected labeling yield for [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was 32 ± 6% (n = 8) and the measured specific activity was 46–182 GBq/μmol (n = 8). The non-decay corrected radiochemical yield for [18F]FAPI-42 was 28 ± 8% (n = 10), and the specific activity was found to be 52–200 GBq/μmol (n = 10). The acceptance criteria for [18F]AlF-P-FAPI is summarized in Table 1 based on the monograph of “2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose ([18F]FDG) injection” in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia.

Table 1.

Tests items, acceptance criteria and test methods for [18F]AlF-P-FAPI.

| Test item | Acceptance criteria | Test method |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Colorless and particle-free | Visual inspection |

| pH | 5.0–8.0 | pH strip |

| Radiochemical purity | Radio-HPLC | |

| [18F]AlF-P-FAPI | ≥90% | |

| Sum [18F]F- and [18F]AlF | ≤5% | |

| Chemical purity | HPLC with UV detector | |

| Amount of AlF-NOTA-P-FAPI, NOTA-P-FAPI, and metal complexes of NOTA-P-FAPI | ≤30 μg per injected volume | |

| Amount of sum of unidentified chemical impurities | ≤10 μg per injected volume | |

| Integrity of sterile filter membrane | Bubble point ≥1.5 bar | Bubble point determination |

| Residual solvent | GC | |

| EtOH | ≤10% v/v | |

| DMSO | ≤0.1% v/v | |

| Total radioactivity | 50–5000 MBq/mL | Dose calibrator |

| Molar activity | ≥3 GBq/μmol | HPLC with UV detector and dose calibrator |

| Maximum injection volume | ≤10 mL | injector |

| Radionuclide identity—approximate half-life (t1/2) | t1/2 = 110 ± 5 min | Two time point radioactivity measurement in dose calibrator |

| Radionuclide identity—gamma spectrometry | Gamma energy is 0.511 ± 0.02 MeV, or a total peak 1.022 ± 0.02 MeV | Gamma spectrum on NaI (Tl) spectrometer |

| Radionuclide purity | ≥99.8% of the activity of fluorine-18 | Gamma spectrum on NaI (Tl) spectrometer |

| Sterility | No growth after 14 days of incubation at 37 °C | The Chinese Pharmacopoeia |

| Bacterial endotoxins | ≤17.5 EU per mL | LAL testa |

Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL).

3.2. In vitro evaluation

The partition coefficients (logD) demonstrated high hydrophilic properties for [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 with values of −2.72 ± 0.07 and −2.43 ± 0.02, respectively, which is similar to the clinically used radiotracer [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 (−2.63 ± 0.04).

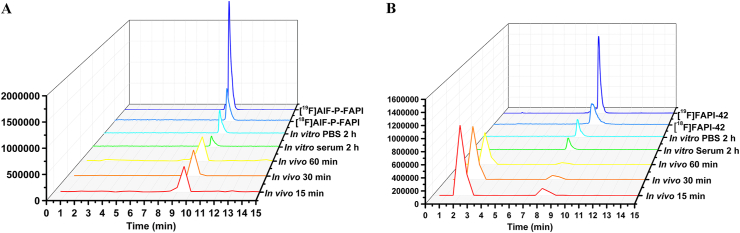

The stability of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 in PBS, mouse serum, and mouse blood is shown in Fig. 2. Determining the in vitro stability in PBS and mouse serum at 37 °C for 2 h indicates high stability across both tracers. We did not observe any decomposition (radiochemical purity >95%) across both tracers using radio-performance liquid chromatography (radio-HPLC). The in vivo stability of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 was also tested from mice blood at different times intervals post-injection (p.i.). The parent of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was greater than 95% within the tested time. Nevertheless, the parent of [18F]FAPI-42 at 15, 30, and 60 min constituted 20%, 15%, and 12%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Identification and stability of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42. Representative HPLC profiles for quality control, reference standard, in vitro stabilities, and in vivo metabolism studies of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI (A) and [18F]FAPI-42 (B).

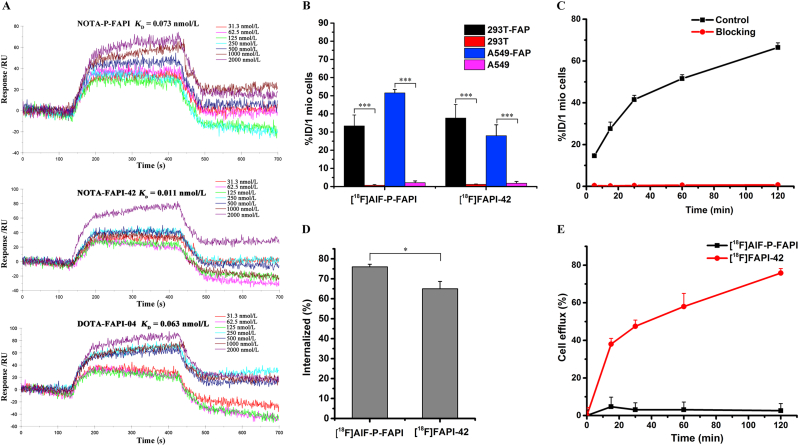

The binding affinity of NOTA-P-FAPI, NOTA-FAPI-42, and DOTA-FAPI-04 for FAP was determined using SPR imaging, the results of which are shown in Fig. 3A. The Kd values for NOTA-P-FAPI and NOTA-FAPI-42 were 0.73 × 10−10 mol/L and 0.11 × 10−10 mol/L, respectively, and comparable to that of DOTA-FAPI-04 (0.63 × 10−10 mol/L). These results indicate that the three radiotracers have a high affinity towards FAP.

Figure 3.

Binding affinity and cellular uptake. (A) The SPR assay determined binding kinetics constants (KD) between non-radioactive reference standards (NOTA-P-FAPI, NOTA-FAPI-42, and DOTA-FAPI-04) and human recombinant FAP proteins. (B) Binding of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 to different cell lines, including cell lines transfected with human FAP, after 60 min of incubation. (C) Uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in A549-FAP cells after incubation for 5–120 min, with and without blocking using DOTA-FAPI-04 as competitor. (D) Internalization of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 into A549-FAP cells after a 60 min incubation period. (E) Efflux kinetics of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 after 60 min of incubation of A549-FAP cells with radiolabeled compounds, followed by incubation with compound-free medium for 5–120 min. The % ID/1 mio cells represents the percentage of total applied dose normalized to 1 million cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD (n = 4), ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

The FAP-positive A549-FAP cells and FAP-negative A549 cells for cell studies were identified in the Supporting Information. The binding properties of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 to FAP were evaluated across different cell lines and cell lines transfected with human FAP (Fig. 3B–E). [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 indicated high uptake in FAP-positive A549-FAP and 293T-FAP cell lines and were significantly blocked by adding the competitor DOTA-FAPI-04. Additionally, FAP-negative A549 and 293T cells did not show any significant uptake of both tracers, suggesting high specificity of both tracers. Time-dependent uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI demonstrated a fast cellular uptake (>14% ID/1 million cells after 5 min; Fig. 3C) with a linearly increasing uptake which reached a maximum of 66.4 ± 2.3% ID/1 million cells at 120 min, and can be significantly blocked by the adding DOTA-FAPI-04 to less than 0.8% ID/1 million cells. Internalization assays in A549-FAP cells demonstrated a rapid and high uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 after 10 min of incubation with 76% and 65% internalized activity, respectively. Efflux experiments demonstrated that [18F]AlF-P-FAPI exhibits a lack of significant cellular efflux in A549-FAP cells, which shows more than 95% of retention of the originally accumulated radioactivity during the 2-h incubation time. The efflux of [18F]FAPI-42 from A549-FAP cells was almost linear during the 2-h incubation time. After the 2-h incubation, approximately 75% of the radioactivity was released from tumor cells.

3.3. Micro-PET/CT and biodistribution studies

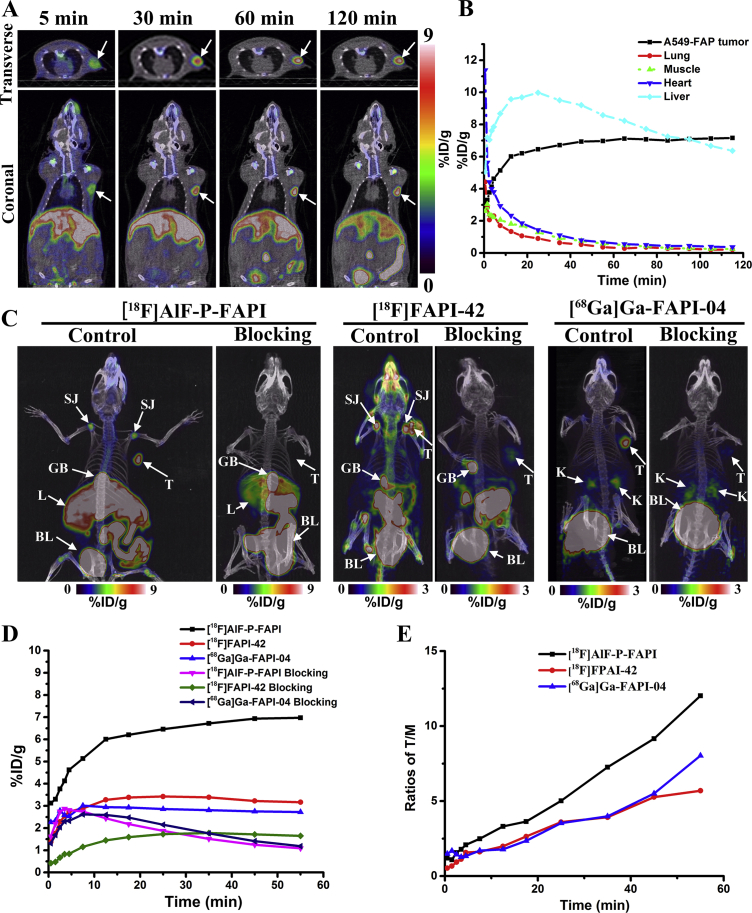

The dynamic micro-PET studies on mice bearing xenografts from human FAP-positive tumor cells were conducted using [18F]AlF-P-FAPI. These results are represented through coronal micro-PET images taken at different time interval p.i. (Fig. 4A). The PET images and time−activity curves demonstrate a rapid and high initial A549-FAP tumor uptake, with a constant increase over the total scan time of 120 min (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Representative micro-PET images and time–activity curves. (A) A series of coronal and transverse dynamic PET images of A549-FAP tumor-bearing mice at 5, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min p.i. of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI. The A549-FAP tumors are delineated in white arrows. (B) Time–activity curves of organs and A549-FAP tumor for 2 h p.i. of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI. (C) MIP at 60 min post-intravenous injection of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, [18F]FAPI-42, and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 with and without DOTA-FAPI-04 as a competitor. Shoulder joint (SJ); tumor (T); gall bladder (GB); liver (L); bladder (BL). (D) Time−activity curves of A549-FAP tumor uptake for 1 h p.i. of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, [18F]FAPI-42, and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 with and without DOTA-FAPI-04 as a competitor. (E) The ratios of tumor-to-muscle for 1 h p.i. of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, [18F]FAPI-42, and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04, respectively.

A comparison of micro-PET imaging of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, [18F]FAPI-42, and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 was conducted using FAP-positive A549-FAP xenografts (Fig. 4C). Maximum intensity projections (MIP) indicated clear visualization of A549-FAP tumors with the three radiotracers. [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 were observed as the predominant liver excretions, as indicated by nonspecific uptake in the gallbladder and intestines. In comparison, [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 was found to be mainly excreted via the renal route. Dynamic measurements for 60 min p.i. revealed that the tumor uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was significantly higher compared to [18F]FAPI-42 and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 (P < 0.05). Therefore, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI had a significantly higher tumor-to-background tissue contrast compared to the other two probes (Fig. 4E). In addition to the uptake in the tumor, both [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 exhibited high uptake in joints (knees and shoulders), with uptake values (in % ID/g) of 5.49 ± 0.25, and 4.07 ± 0.04, respectively, at 1-h p.i. However, [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 accumulated within the joints to a lower extent (0.90 ± 0.07% ID/g). The blocking study for the tested three tracers in mice bearing A549-FAP tumors indicated a remarkable decrease in uptake by tumors and joints (Fig. 4C and D), demonstrating the specificity of radiotracers for its target protein.

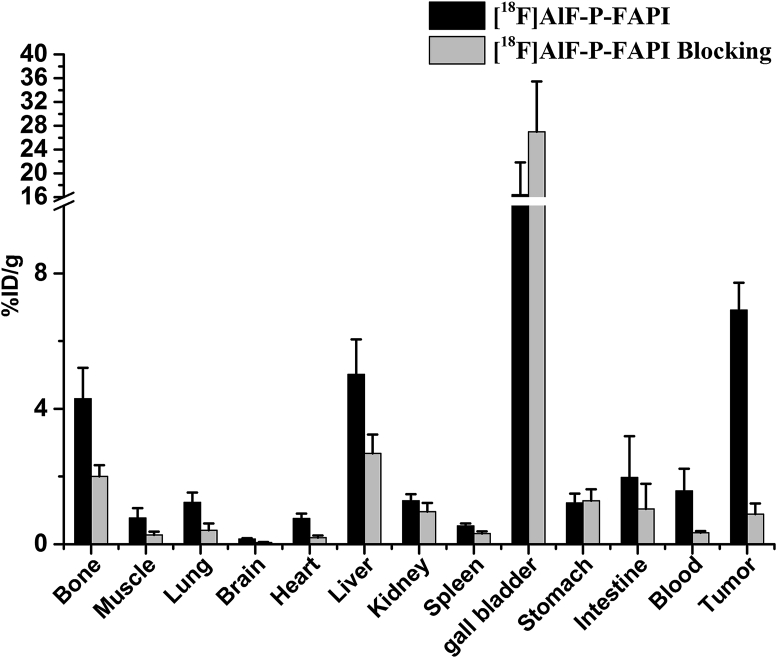

We conducted biodistribution studies of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI with and without DOTA-FAPI-04 as a competitor 1 h after injection to further confirm micro-PET imaging quantification (Fig. 5). High and specific uptake of tracers was observed in the A549-FAP tumors. The uptake in FAP-positive organs, including tumor and bone, was significantly reduced via co-injection of an excess of DOTA-FAPI-04, indicating FAP-specific targeting.

Figure 5.

Biodistribution studies of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in A549-FAP bearing mice 1 h after intravenous injection. All the data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4).

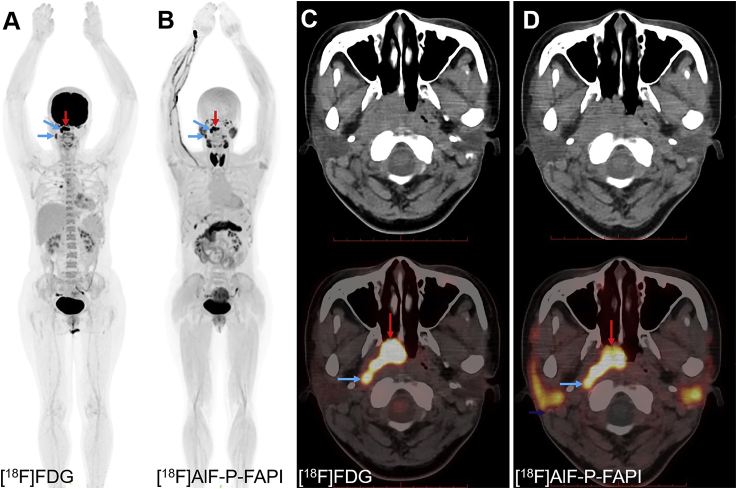

3.4. PET/CT imaging and analysis

The patient with nasopharyngeal cancer tolerated the examination and did not report any subjective effects after injection of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI. There were no drug-related adverse events or physiologic responses. In the patient, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI PET/CT showed intense uptake of radioactivity within the primary tumor (SUVmax of 14.1) and lymph node metastases (SUVmax of 13.7 and 8.6, respectively), similar to [18F]FDG PET/CT (primary tumor: SUVmax of 17.6; lymph node metastases: SUVmax of 11.9 and 7.1, respectively, Fig. 6). The uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI within the kidneys and bladder indicated that the main excretion organ was the kidneys. In addition, thyroid glands, the submandibular glands, parotid glands, and pancreas were clearly visible at 1 h p.i. The primary tumor lesion and lymph node metastases were clearly defined on the [18F]AlF-P-FAPI PET/CT due to the low physiologic uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI within the brain. These results suggest that this method has the potential to be translated into a clinical setting.

Figure 6.

PET/CT images of a 41-year-old patient with newly diagnosed nasopharyngeal cancer. (A) and (C) The patient was examined using [18F]FDG in September 2020. (B) and (D) The second examination with [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was conducted 24 h later. [18F]AlF-P-FAPI images indicated tumor metastases uptake corresponding to [18F]FDG PET/CT images, represented by the arrow. The primary tumor is indicated by red arrows; lymph node metastases are indicated by blue arrows.

4. Discussion

The main goal of the present study was to identify a novel 18F-labeled FAP tracer for cancer imaging. Here, we report the synthesis and preclinical characterization of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, as well as the direct comparison with patent tracers [18F]FAPI-42 and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04. In addition, a first-in-man study was conducted using [18F]AlF-P-FAPI.

McBride et al.27 developed direct radiolabeling of peptides and proteins through chelation with Al18F27. Our previous work also demonstrated that radiolabeling of peptides through complexation of Al18F by radiometal chelator NOTA could be good labeling yield and automated production28. We designed a novel precursor NOTA-P-FAPI using a PEG2 linker between the quinolone-based pharmacophore and the NOTA chelator to take advantage of the Al18F-labeling method. The PEG linker was used to improve the in vivo half-life and metabolic stability19,20. NOTA-FAPI-42 was obtained by substituting the DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) motif of DOTA-FAPI-04 by the NOTA motif. Interestingly, the binding affinity of NOTA-FAPI-42 was approximately six-fold that of the known tracer DOTA-FAPI-04, while NOTA-P-FAPI displayed a similar binding affinity to DOTA-FAPI-04.

The preparation of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 was efficient and convenient, using an automated synthesis module with high molar activities. Due to the effect of the linker, the lipophilicity of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was lower than that of [18F]FAPI-42. Meanwhile, stability studies did not find any degradation of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in vitro or in vivo, whereas [18F]FAPI-42 was degraded in vivo. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that using PEG can increase hydrophilicity and improve half-life in vivo19,20.

Cellular uptake studies using FAP-positive and FAP-negative cells indicated that both tracers were rapidly internalized with specific binding to FAP. In addition, the amount of internalized activity of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was higher than that of [18F]FAPI-42. Efflux experiments demonstrated that [18F]AlF-P-FAPI was significantly slower compared to [18F]FAPI-42, which might be caused by the higher stability of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI as compared to [18F]FAPI-42.

The micro-PET imaging results demonstrated that [18F]AlF-P-FAPI had significantly higher tumor uptake compared to the other two patent tracers, while [18F]FAPI-42 had comparable tumor uptake in comparison to [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04. Moreover, the uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in the tumor was visualized at 30 min p.i., with low uptake in all the non-target organs, except for liver and intestine decline over time, leading to a constant improvement in the tumor-to-background ratios. In addition, both [18F]AlF-P-FAPI and [18F]FAPI-42 exhibited higher uptake in joints (knees and shoulders), compared to [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04, consistent with the literature reported for [18F]FGlc-FAPI7. It has been reported that FAP is expressed in BMSCs of mice, which are capable of directed migration towards various tumor types, involving tissue remodeling2,29,30. The ex vivo distribution studies of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI indicated the highest uptake within the gall bladder, indicating excretion mainly through the hepatobiliary pathway. The compound DOTA-FAPI-04 has been proven to be a FAP competitor in the previous literature18. The in vivo blocking experiment demonstrated that co-injection of DOTA-FAPI-04 significantly diminished the tumor and joints uptake of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, suggesting its high specificity for FAP within these regions.

Based on prior preclinical studies, we conducted the pilot clinical study of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in one nasopharyngeal cancer patient to examine the potential clinical application of FAP imaging. There were no subjective effects reported by the patient p.i. with a tracer. The excretion pathway of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in human predominantly renal elimination is similar to that of reported tracers [18F]FAPI-74 and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-048,31. Due to different species, the excretion of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI in humans is different from that of mice. Our preliminary experience in one patient showed that [18F]AlF-P-FAPI had a high level of physical uptake in thyroid glands, submandibular glands, parotid glands, and pancreas, which has also been observed in clinical studies for [18F]FAPI-4232,33. Compared to [18F]FDG, the pilot study of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI demonstrated comparable tumor detectability in nasopharyngeal cancer. [18F]AlF-P-FAPI, as a FAP tracer for PET imaging, has a higher specificity compared to [18F]FDG and is independent of blood-sugar and physical activity. Although limited by the number of patients available, our pilot study of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI demonstrated promising imaging properties for cancer associated fibroblasts imaging. Furthermore, a study directly comparing 18F-labeled FAP tracer versus [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 in tumor patients is underway.

5. Conclusions

We developed a fluorine-18 labeled FAP-targeting tracer through automated preparation for imaging of cancer associated fibroblasts. The preclinical evaluation of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI exhibited suitable characteristics for tumor imaging of FAP expression in mice. Compared to patent tracers [18F]FAPI-42 and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04, [18F]AlF-P-FAPI exhibited a higher tumor uptake and retention. The primary clinical studies have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of [18F]AlF-P-FAPI for further clinical translation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mogo Edit Experts (http://www.mogoedit.com) for the English language editing of this manuscript. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701729, 91949121), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515011099, China), Outstanding Youths Development Scheme of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2017J010, China), and Nanfang Hospital Talent Introduction Foundation of Southern Medical University (123456, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.09.032.

Contributor Information

Jin Su, Email: sujin@gird.cn.

Ganghua Tang, Email: gtang0224@smu.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Study conception and design, Kongzhen Hu, Ganghua Tang, and Jin Su; acquiring data, Kongzhen Hu, Junqi Li, Yong Huang, Li Li, Shimin Ye, and Yanjiang Han; analysis and interpretation of data, Kongzhen Hu, Lijuan Wang, Yong Huang, Junqi Li, and Jin Su; diagnostic imaging, Lijuan Wang and Hubing Wu; data management, Shun Huang; drafting the manuscript, Kongzhen Hu; revising the manuscript, Ganghua Tang and Jin Su. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Busek P., Mateu R., Zubal M., Kotackova L., Sedo A. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in cancer—prospects and caveats. Front Biosci-Landmark. 2018;23:1933–1968. doi: 10.2741/4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tran E., Chinnasamy D., Yu Z., Morgan R.A., Lee C.C.R., Restifo N.P., et al. Immune targeting of fibroblast activation protein triggers recognition of multipotent bone marrow stromal cells and cachexia. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1125–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scanlan M.J., Raj B.K.M., Calvo B., Garin-Chesa P., Sanz-Moncasi M.P., Healey J.H., et al. Molecular cloning of fibroblast activation protein α, a member of the serine protease family selectively expressed in stromal fibroblasts of epithelial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5657–5661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Šimková A., Bušek P., Šedo A., Konvalinka J. Molecular recognition of fibroblast activation protein for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Biochim Biophys Acta-Proteins Proteomics. 2020;1868:140409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu F., Qi L., Liu B., Liu J., Zhang H., Che D.H., et al. Fibroblast activation protein overexpression and clinical implications in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H., Lee Y., Lee H., Kim J.W., Hwang J.H., Kim J., et al. The prognostic significance of cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2017;39:1–9. doi: 10.1177/1010428317718403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toms J., Kogler J., Maschauer S., Daniel C., Schmidkonz C., Kuwert T., et al. Targeting fibroblast activation protein: radiosynthesis and preclinical evaluation of an 18F-Labeled FAP inhibitor. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:1806–1813. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.242958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giesel F.L., Adeberg S., Syed M., Lindner T., Jiménez-Franco L.D., Mavriopoulou E., et al. FAPI-74 PET/CT using either 18F-AlF or cold-kit 68Ga labeling: biodistribution, radiation dosimetry, and tumor delineation in lung cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:201–207. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.245084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer C., Dahlbom M., Lindner T., Vauclin S., Mona C., Slavik R., et al. Radiation dosimetry and biodistribution of 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET imaging in cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:1171–1177. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.236786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loktev A., Lindner T., Burger E.M., Altmann A., Giesel F., Kratochwil C., et al. Development of fibroblast activation protein-targeted radiotracers with improved tumor retention. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:1421–1429. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.224469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loktev A., Lindner T., Mier W., Debus J., Altmann A., Jäger D., et al. A tumor-imaging method targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1423–1429. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.210435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hintz H.M., Gallant J.P., Vander Griend D.J., Coleman I.M., Nelson P.S., LeBeau A.M. Imaging fibroblast activation protein alpha improves diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer with positron emission tomography. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4882–4891. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altmann A., Haberkorn U., Siveke J. The latest developments in imaging of fibroblast activation protein. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:160–167. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.244806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi X., Xing H., Yang X., Li F., Yao S., Zhang H., et al. Fibroblast imaging of hepatic carcinoma with 68Ga-FAPI-04 PET/CT: a pilot study in patients with suspected hepatic nodules. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:196–203. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04882-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L.J., Zhang Y., Wu H.B. Intense diffuse uptake of 68Ga-FAPI-04 in the breasts found by PET/CT in a patient with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2021;46:e293–e295. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windisch P., Röhrich M., Regnery S., Tonndorf-Martini E., Held T., Lang K., et al. Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) specific PET for advanced target volume delineation in glioblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2020;150:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kratochwil C., Flechsig P., Lindner T., Abderrahim L., Altmann A., Mier W., et al. 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT: tracer uptake in 28 different kinds of cancer. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:801–805. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.227967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindner T., Loktev A., Altmann A., Giesel F., Kratochwil C., Debus J., et al. Development of quinoline-based theranostic ligands for the targeting of fibroblast activation protein. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1415–1422. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.210443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z., Li Z.B., Cai W., He L., Chin F.T., Li F., et al. 18F-labeled mini-PEG spacered RGD dimer (18F-FPRGD2): synthesis and microPET imaging of αvβ3 integrin expression. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1823–1831. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penchala S.C., Miller M.R., Pal A., Dong J., Madadi N.R., Xie J., et al. A biomimetic approach for enhancing the in vivo half-life of peptides. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:793–798. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habekorn U, Loktev A, Lindner T, Mier W, Giesel F, inventors; Heidelberg Univerisity, assignee. FAP inhibitor. WO2019154886A1. August 15, 2019.

- 22.Huang Y., Li H., Ye S., Tang G., Liang Y., Hu K. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of an Al18F radio fluorinated bivalent PSMA ligand. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;221:113502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tshibangu T., Cawthorne C., Serdons K., Pauwels E., Gsell W., Bormans G., et al. Automated GMP compliant production of [18F]AlF-NOTA-octreotide. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem. 2020;5:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s41181-019-0084-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao S., Zhang B., Yang M., Zhu J., Li H. Systematic profiling of histone readers in arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Rep. 2018;22:1090–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S., Li H., Han Y., Fu L., Ren Y., Zhang Y., et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 18F-Labeled peptide for gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor imaging. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2019;2019:5635269. doi: 10.1155/2019/5635269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan H., Sui X., Yin H., Yu H., Gu Y., Chen S., et al. Total-body PET/CT using half-dose FDG and compared with conventional PET/CT using full-dose FDG in lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:1966–1975. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McBride W.J., Sharkey R.M., Karacay H., D'Souza C.A., Rossi E.A., Laverman P., et al. A novel method of 18F radiolabeling for PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:991–998. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang S., Wu H., Li B., Fu L., Sun P., Wang M., et al. Automated radiosynthesis and preclinical evaluation of Al[18F]F-NOTA-P-GnRH for PET imaging of GnRH receptor-positive tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 2020;82–83:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan R.N., Psaila B., Lyden D. Niche-to-niche migration of bone-marrow-derived cells. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamada H., Kobune M., Nakamura K., Kawano Y., Kato K., Honmou O., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) as therapeutic cytoreagents for gene therapy. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H., Pang Y., Wu J., Zhao L., Hao B., Wu J., et al. Comparison of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-FAPI-04 and [18F]FDG PET/CT for the diagnosis of primary and metastatic lesions in patients with various types of cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1820–1832. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04769-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S., Zhou X., Xu X., Ding J., Liu S., Hou X., et al. Clinical translational evaluation of Al18F-NOTA-FAPI for fibroblast activation protein-targeted tumour imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;41:4259–4271. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang X., Wang X., Shen T., Yao Y., Chen M., Li Z., et al. FAPI-04 PET/CT Using [18F]AlF labeling strategy: automatic synthesis, quality control, and in vivo assessment in patient. Front Oncol. 2021;11:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.649148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.