Abstract

Simultaneous fractures of the medial and lateral hallucal sesamoids from sports injuries are an extremely uncommon occurrences, with only one case reported in a hurdler. We describe an unusual injury in a basketball player resulting in simultaneous fractures of the medial and lateral hallucal sesamoid bones, a presentation, which we believe has not been reported before in the literature. With a growing interest in sports, the frequency of such injuries will undoubtedly rise. We highlight the clinical characteristics, biomechanical mechanism, role of complementary cross-sectional imaging in the diagnosis of hallucal sesamoid fractures. This case report emphasizes the need of high index of suspicion in reaching conclusive diagnosis of such rare injuries to prevent long term complications such as avascular necrosis or non-union and facilitate early return to sporting activities.

Keywords: Bipartite hallucal sesamoid, Foot, Fracture, Basketball, Radiology, Sports medicine

1. Introduction

A sesamoid bone is an rounded, osseous structure embedded in a tendon with a purpose to reinforce and decrease stress on that tendon. In the foot, two hallucal sesamoids (medial/tibial and lateral/fibular) are located on the plantar surface of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint.1 The hallucal sesamoids are embedded within the flexor hallucis brevis (FHB) tendon, separated by a crista/intersesamoid ridge in which the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon courses to the distal phalanx. (Fig. 1). The hallucal sesamoids provide a smooth surface over which the big toe flexor tendons can glide and function as pulleys stabilizing the MTP joint.2 Additionally, the hallucal sesamoids, particularly the medial, act in absorbing the loading forces and have been reported to withstand more than 300% of body weight.3 Loading pressures on the sesamoids are even greater when performing high-impact athletic activity such as running, jumping or gymnastics.4 Furthermore, improper landing on the toes can lead to excessive loading forces resulting in compression of the sesamoids, thereby rendering them vulnerable and prone to a spectrum of injuries.4,5 Hallucal sesamoid fractures can be missed on radiographs as they can be mistaken for bipartite sesamoids, a commonly encountered normal variant (Table 1). If undetected, sesamoid fractures may disrupt surrounding blood supply, leading to delayed union, nonunion or avascular necrosis (AVN) of the sesamoids.6 Cross-sectional imaging with Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging plays a crucial role in confirming a sesamoid injury.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of plantar first tarso-metatarsal joint with medial and lateral hallucal sesamoid arrangement. 1) Sesamoid-phalangeal ligament 2) Medial sesamoid 3) Intersesamoid ridge 4) Lateral sesamoid 5) Adductor hallucis 6) Flexor hallucis brevis 7) Flexor hallucis longus.

Table 1.

Clinico-radiological features of common pathologies affecting the sesamoid bones of the hallux (Big toe) of the foot.

| Aetiology | Clinical findings | Radiograph findings | CT and MRI findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesamoid fracture | Acute trauma | Sudden onset of point pain, tenderness and swelling post-trauma/sports injury | - Not corticated at the fractured margins. - Corticated margins may be difficult to depict due to bony overlap on the AP/lateral views of the foot are the commonly performed views. However, sometimes Oblique radiographs better demonstrate the fracture margins. Often, it must be noted, both the sesamoids are not completely separated from the overlying bones. - Radiographs may take up to 6 months to show structural changes in a missed fracture. Therefore, the need for axial/sagittal/coronal CT to detect sesamoid fractures. |

CT:

|

| Bipartite/multipartite variant | Multiple ossification centres and failure of the fragments to fuse at maturity | None | Well corticated | CT:

|

| AVN (avascular necrosis) | Chronic microtrauma predisposes to AVN if the tenuous blood supply is disrupted | Longstanding point pain, tenderness and history of repetitive activities causing microtrauma | No specific findings in early disease. Late disease: - sclerosis, collapse and fragmentation of the cortex - superimposed secondary degenerative changes |

CT:

|

| Sesamoiditis | Chronic inflammation of the sesamoids and its surrounding structures. Diagnosis of exclusion. Predisposing factors are like that of fractures/AVN |

Insidious onset, low-grade pain | Rules out other causes of sesamoid injury. Late sesamoiditis: nonspecific changes such as sclerosis and fragmentation. |

CT:

|

Abbreviations: CT= Computed Tomography Scan; MRI = Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Consequently, by reporting our experience of this patient with simultaneous fractures of the medial and lateral hallucal sesamoids, we want to highlight the need of vigilance to identify and manage this easily missed injury.

2. Case report

A 22-year-old male, varsity basketball player with no significant past medical history sustained an acute injury to his right fore foot after landing on it following a jump shot. He was unable to weight bear after the injury and limped out of the game with pain.

Clinical examination revealed bruising and focal swelling on the plantar side of the big toe. He demonstrated maximum point tenderness on the plantar aspect of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Active plantarflexion of the great toe was possible with difficulty due to pain. Non-weight bearing radiographs of the foot (anterior-posterior AP, lateral and oblique views) revealed two osseous structures at the site of the medial sesamoid and another two at the lateral sesamoid. (Fig. 2). However, the adjacent margins of the two sesamoids were not well corticated, unlike the rest of the sesamoid surfaces. This raised the suspicion of hallucal sesamoid fractures rather than the commoner finding of bipartite medial and lateral sesamoids. Confirmation of the injury was done with the help of CT scan. CT scan clearly demonstrated a thin linear horizontal fracture of both medial and lateral sesamoids. (Fig. 3). A lack of corticated margins along the fracture lines was clearly depicted, thus confirming the diagnosis of fractures of both medial and lateral hallucal sesamoids. There were no other associated injuries in the rest of the foot. The patient was reassured about the nature of the injury and treated conservatively with the principles of R. I. C. E (Rest, ice, compression bandage and elevation). Full-weight bearing was permitted but he was advised to avoid lunging stop- and- go movements for 4 weeks. He made full recovery following gradual return to sports and competitive basketball after 3 months.

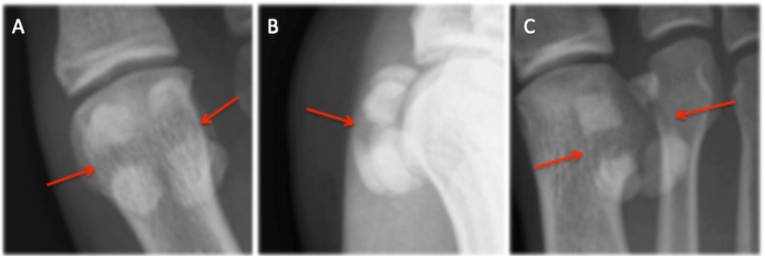

Fig. 2.

Plain radiograph of Injured Right foot, AP (A), lateral (B) and oblique (C) views. Bilateral medial and lateral hallucal sesamoid fractures. Note the absence of cortication along the fracture margins.

Fig. 3.

Right foot CT reformats sagittal (A) medial sesamoid, sagittal (B) lateral sesamoid and coronal (C) medial and lateral sesamoid fractures. Note the acute, post-traumatic horizontal fractures of the medial and lateral hallucal sesamoids with sharp fracture margins, lack of cortication and mild separation between the fractured fragments. These features are consistent with fractures of the medial and lateral hallucal sesamoids, differentiating them from bipartite sesamoids (normal variant).

3. Discussion

To date, there are only four publications of the medial and lateral hallucal sesamoid fractures in literature, one in orthopedics, one in sports medicine and two in surgery.7, 8, 9, 10 This suggests the rarity of such an injury.

In 1985, a case by Hulkko et al. published 15 cases of stress fractures of the sesamoid bones of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint in athletes with just one case in which both sesamoids were affected.7 Abraham et al. have discussed two cases of acute post-traumatic sesamoid fractures. Both cases were due to forced hyperextension injuries, one from stepping on an unstable object and the other caused by work-related trauma.8 A third case study by Van Pelt et al. from 2007 presented open fractures of both sesamoids with an associated first MTP joint dislocation.9 Although the above three publications reported both medial and lateral sesamoid fractures, the mechanism of injury vastly differs from our case study. The only comparable publication is a case study by Mouhsine et al. who describe a 30-year-old hurdler acutely fracturing both sesamoids during training.10

Our case, however, is that of a basketball related sports injury and not reported before. Biomechanically, in our patient it appears landing after a jump shot lead to one abrupt, rapid point of contact of the forefoot with forced dorsiflexion of the big toe. This resulted in simultaneous medial and lateral hallucal sesamoid fractures of the right great toe.

Hallucal sesamoids are vulnerable to acute and chronic injuries. Acute fractures occur when immense force is applied onto the hallux (e.g. landing on the foot after a basketball jump as in our patient) or due chronic, stress fractures secondary to repetitive low-level trauma and overuse.4 Commonly associated injuries with hallux sesamoid fractures include Turf toe or exacerbation of a previous stress fracture of the sesamoid or Sesamoiditis. A ‘Turf toe’ is an injury of the soft tissue surrounding the big toe joint without associated fractures.

Sesamoiditis is an overuse injury involving chronic inflammation of the sesamoid bones. Plain radiographs and if required CT or MRI can help in diagnosis of these conditions.

The prevalence of bipartite sesamoids may be as high as 30% with bilateral bipartite sesamoids being the most common (80–90%).1 Consequently, sesamoid fractures can be overlooked as bipartite sesamoids in clinical practice as the two entities appear almost identical on plain radiographs. This can lead delayed diagnosis, nonunion or AVN of the sesamoids. Symptomatic nonunion are treatable with autogenous bone grafting for nonunion. Partial or total Excision with sesamoidectomy is another option that can be undertaken. Cross-sectional imaging allows definitive diagnosis. Once the diagnosis was confirmed on CT, it allowed us to reassure our patient, plan conservative management with gradual return to competitive sports since most acute sesamoid injuries respond well to supervised, nonoperative treatment.

Conflict of interest

None.

Statement of funding

None.

Contributors

AR and VK involved in Conceptualization and writing the original draft of manuscript, literature search, planning, conduct and editing. KPI Supervised the project and also involved in Image and manuscript editing. All authors have read and agreed the final draft submitted.

Funding statement

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement and conflict of interest statement

Nothing to disclose. “The authors declare no conflict of interest”.

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

Contributor Information

Akhila Rachakonda, Email: rakhila96@hotmail.com.

Venkata Kollimarla, Email: sai.kollimarla@gmail.com.

Karthikeyan P. Iyengar, Email: kartikp31@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Nwawka O.K., Hayashi D., Diaz L.E., et al. Sesamoids and accessory ossicles of the foot: anatomical variability and related pathology. Insights Imag. 2013 Oct;4(5):581–593. doi: 10.1007/s13244-013-0277-1. Epub 2013 Sep 5. PMID: 24006205; PMCID: PMC3781258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sims A.L., Kurup H.V. Painful sesamoid of the great toe. World J Orthoped. 2014 Apr 18;5(2):146–150. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i2.146. PMID: 24829877; PMCID: PMC4017307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boike A., Schnirring-Judge M., McMillin S. Sesamoid disorders of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2011 Apr;28(2):269–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2011.03.006. vii. PMID: 21669339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein C.J., Sugimoto D., Slick N.R., et al. Hallux sesamoid fractures in young athletes. Physician Sportsmed. 2019 Nov;47(4):441–447. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2019.1622246. Epub 2019 Jun 5. PMID: 31109214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson E.G. Injuries to the hallucal sesamoids in the athlete. Foot Ankle. 1987 Feb;7(4):229–244. doi: 10.1177/107110078700700405. PMID: 3817668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartosiak K., McCormick J.J. Avascular necrosis of the sesamoids. Foot Ankle Clin. 2019 Mar;24(1):57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2018.09.004. PMID: 30685013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulkko A., Orava S., Pellinen P., Puranen J. Stress fractures of the sesamoid bones of the first metatarsophalangeal joint in athletes. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1985;104(2):113–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00454250. 10.1007/BF00454250. PMID: 4051695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham M., Sage R., Lorenz M. Tibial and fibular sesamoid fractures on the same metatarsal: a review of two cases. J Foot Surg. 1989 Jul-Aug;28(4):308–311. PMID: 2794362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Pelt M., Brown D., Doyle J., LaFontaine J. First metatarsophalangeal joint dislocation with open fracture of tibial and fibular sesamoids. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2007 Mar-Apr;46(2):124–129. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2006.10.012. 10.1053/j.jfas.2006.10.012. PMID: 17331873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouhsine E., Leyvraz P.F., Borens O., Ribordy M., Arlettaz Y., Garofalo R. Acute fractures of medial and lateral great toe sesamoids in an athlete. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004 Sep;12(5):463–464. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0472-6. Epub 2004 Jan 10. PMID: 14716474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]