Abstract

Research question

Can the SARS-CoV-2 virus injure the ovaries?

Design

An observational before-and-after COVID-19 study at an academic medical centre. A total of 132 young women aged 18–40 were enrolled; they were tested for reproductive function in the early follicular phase, and their information was obtained from hospital data between January 2019 and June 2021. Serum FSH, LH, oestradiol, the ratio of FSH to LH and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) concentrations were measured for each patient both before and after COVID-19 disease.

Results

In women with unexplained infertility, the median serum AMH concentrations (and ranges) were 2.01 ng/ml (1.09–3.78) and 1.74 ng/ml (0.88–3.41) in the pre-COVID-19 disease and post-COVID-19 disease groups, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of serum concentrations of AMH between pre- and post-illness (P = 0.097). Serum FSH, LH, FSH/LH ratio and oestradiol concentrations of the patients before COVID-19 illness were similar to the serum concentrations of the same patients after COVID-19 illness.

Conclusion

According to these study results and recent studies investigating the effect of COVID-19 on ovarian reserve, it is suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 virus does not impact ovarian reserve; however, menstrual status changes may be related to extreme immune response and inflammation, or psychological stress and anxiety caused by the COVID-19 disease. These menstrual status changes are also not permanent and resolve within a few months following COVID-19 illness.

Keywords: COVID-19 disease, Ovarian injury, Ovarian reserve, Reproductive function, SARS-CoV-2 virus

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, and its associated disease, COVID-19, first appeared in Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread across the world, infecting many people. As of 14 September 2021, the number of cases worldwide was determined as 224 million and approximately 4.6 million people died (www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019). As reported in recent studies, the novel virus can affect many systems of the body such as the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, nervous and reproductive systems, as well as the respiratory systems. Although there is much research about COVID-19, there are still many unanswered questions and concerns. One of these is undoubtedly whether SARS-CoV-2 virus infection affects ovarian reserve. Up to now, few studies have been published investigating the effect of COVID-19 disease on the reproductive system. Because recent publications evaluating young women infected with COVID-19 show changes in menstrual status and reproductive hormones, it is thought that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can injure the ovaries (Ding et al., 2021a; Li et al., 2021). The menstrual cycle is an important marker of reproductive function and can be influenced by many factors such as ovarian reserve, the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis, infections, psychiatric stress and medications (Louis et al., 2011; Rooney and Domar, 2018). Other important markers of reproductive function are FSH, LH, oestradiol, the ratio of FSH to LH and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) (Tal and Seifer, 2017).

AMH is a major biomarker evaluating the ovarian follicle reserve and representing oocyte quantity and quality (Iwase et al., 2015). AMH belongs to the transforming growth factor-beta family, is secreted by the granulosa cells of growing follicles which are pre-antral and antral follicles less than 8 mm in diameter (La Marca et al., 2009; Moolhuijsen and Visser, 2020). AMH inhibits FSH-dependent oocyte recruitment, and plays a significant part in the development of ovarian follicles (Iwase et al., 2015).

As reports to date on the impact of COVID-19 on the ovarian reserve are limited and inconsistent, this study aimed to investigate whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus could injure the ovaries. The aim was to compare values for biomarkers of reproductive function in young women both before and after COVID-19 infection.

Materials and methods

Participants

The methodology of this study was designed as a quasi-experiment, and observations and measurements were performed at the Kayseri Medical Faculty of Health Sciences University. A total of 2548 young women aged 18–40 years were included in the study; their information was obtained from hospital data between January 2019 and April 2021, and they underwent reproductive function tests in the early follicular phase (AMH, FSH, LH, oestradiol due to non-ovarian infertility). Initially, the following were excluded from the study: women with ovarian disease or ovarian surgery, pregnant or lactating, chronic disorders, malignancy, use of hormonal contraceptives, use of fertility treatments (i.e. using FSH), chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In addition, 318 women were excluded from the study because they were vaccinated for COVID-19. Secondly, the remaining participants in the study were questioned about whether they had COVID-19 disease by the Ministry of Health data system. COVID-19 disease was described as a positive result by a real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of throat swab specimens (Huang et al., 2020). According to the severity of the COVID-19 disease, it was divided into mild and severe illness as specified in guidelines from the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America (Metlay et al., 2019). It was eventually determined following this query that 264 participants were infected with COVID-19 disease. All positive PCR test dates of the participants were recorded. Thirdly, 117 women were excluded from the study because the reproductive function test measurement dates were in the post-illness period. The remaining 190 participants were invited by telephone to the study hospital to re-evaluate the tests of reproductive function 3 months after recovery from COVID-19. Forty-three declined the invitation; 15 were determined as pregnant. In the end, 132 women accepted the invitation and the study continued with these patients. Time frames between assessments both before and after COVID-19 disease were calculated and recorded.

Demographic characteristics such as age, body mass index (BMI), gravida, parity, menstrual status before and after COVID-19, and medical history were obtained from the patients and saved. Further evaluation was performed of each patient's menstrual status, such as menstrual blood volume (according to the number of pads changed per day), duration (number of days she had her menstruation), and menstrual period for 3 months post-COVID-19 disease. Patients were also asked whether these aspects of menstrual status had changed compared with the pre-illness period. A menstrual irregularity was defined as patients with both shortened (<27 days) and prolonged (>35 days) menstrual periods. All assessments and recordings were objectively made by same person (ICM).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Kayseri City Education and Research Hospital on 14 July 2021 (441/2021), and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Hormone assays

Venous blood samples were obtained from each of the participants during the early follicular phase of their menstrual period. Serum AMH, FSH, LH and oestradiol concentrations were analysed with a human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Elecsys and cobas e411 analysers, Roche, Switzerland). All of these samples were measured in the same laboratory immediately after collection. The lowest amount of AMH that could be detected with a 95% probability in a sample was 0.01 ng/ml. A range of AMH measurements from 0.03 to 23 ng/ml supplies excellent low-level sensitivity. Measurements of oestradiol in the range of 20–4800 pg/ml with an intra-assay variability 21%; of LH in the range of 0.2–250 mIU/ml with an intra-assay variability of 3.8%; and of FSH in the range of 0.2–200 mIU/ml with an intra-assay variability of 3.5% were determined in the same laboratory.

Statistical analysis

All data obtained from the study participants were divided into two groups as pre- and post-COVID-19 disease and then statistically analysed using SPSS for Windows, Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The values were expressed as mean ± SD or n (%), median and interquartile range (IQR). The log-transformed value of AMH and log(AMH) were also used as an outcome variable.

Student's t-test was used to compare parametric data; the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare non-parametric data. Categorical data were compared using Pearson's chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact test. The difference among the groups was considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 147 fertile women with COVID-19 disease were evaluated for this study. Pregnancy was observed in 15 participants after COVID-19 illness and these pregnant women were excluded from the study and so 132 participants were further evaluated. Table 1 provides demographic characteristics of all study participants. The median age of the subjects was 28 years and the median BMI was 23.6 kg/m2. Three of them had severe COVID-19 disease and 112 of them received antiviral treatment for COVID-19. The time between the first (pre-COVID) AMH measurement and the post-COVID measurement is also presented in Table 1. As the time frame between measurements seems to be quite homogeneous and short, it was not considered necessary to correct for this time difference.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic | 132 women after COVID-19 illness |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28 (23–34) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.6 (19.71–26.11) |

| Gravida | 2 (2–3) |

| Parity | 1 (1–2) |

| Pregnancy after COVID-19 illness | 15/147 (10.2) |

| Antiviral treatment | 112/132 (84.8) |

| Smoker | 7/132 (5.3) |

| Severe COVID-19 diseasea | 3/132 (2.3) |

| Time frame between assessments (months) | 9 (7–12) |

| Before COVID-19 time period (months) | 5 (4–7) |

| After COVID-19 time period (months) | 4 (4–7) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) and n (%).

According to the severity of the COVID-19, it was divided into mild and severe illness as specified in the 2019 guidelines from the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Menstrual conditions of the study patients in the pre-COVID-19 period was compared with the post-COVID-19 period and is presented in Table 2 . Twelve (9.1%) of the participants had irregular menstruation before COVID-19 disease while 21 (15.9%) of them had irregular menstruation after COVID-19 disease (P = 0.094). The study patients had a significant reduction in menstrual volume for 3 months after their illness (P = 0.035). While there was less bleeding in the menstrual period of 10 participants before COVID-19 disease, there was a decrease in the amount of bleeding in 21 participants after COVID-19 disease (7.6% versus 15.9%, P = 0.035). There was no significant difference between groups in terms of increased menstrual volume. Twelve participants in the pre-COVID-19 group had a large amount of bleeding in their menstrual period and 16 of them had an increased menstrual volume in the post-illness group (9.1% versus 12.1%, P = 0.215). Spontaneous pregnancy was observed in 15/147 participants (10.2%) after COVID-19 illness.

Table 2.

Comparison of the reproductive function between groups

| Before COVID-19 disease | After COVID-19 disease | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual volume changes last 3 months | |||

| Decrease in menstrual volume | 10/132 (7.6) | 21/132 (15.9) | 0.035a |

| Increase in menstrual volume | 12/132 (9.1) | 16/132 (12.1) | 0.215a |

| Irregular menstrual cycle | 12/132 (9.1) | 21/132 (15.9) | 0.094a |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 2.01 (1.09–3.78) | 1.74 (0.88–3.41) | 0.097b |

| Log(AMH) | 0.481 ± 0.238 | 0.435 ± 241 | 0.118b |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 4.91 (1.99–8.58) | 5.41 (2.29–8.99) | 0.118b |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 4.14 (2.08–7.07) | 4.72 (1.90–8.11) | 0.201b |

| Oestradiol (ng/ml) | 55.42 (25.21–79.14) | 58.86 (28.61–78.90) | 0.181b |

| FSH/LH | 1.42 (0.96–1.88) | 1.61 (0.89–1.92) | 0.268b |

Data are presented as n (%) and median (interquartile range) and mean ± SD.

AMH = anti-Müllerian hormone.

Categorical data were compared using Pearson's chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact test.

Student's t-test was used to compare parametric data; the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare non-parametric data.

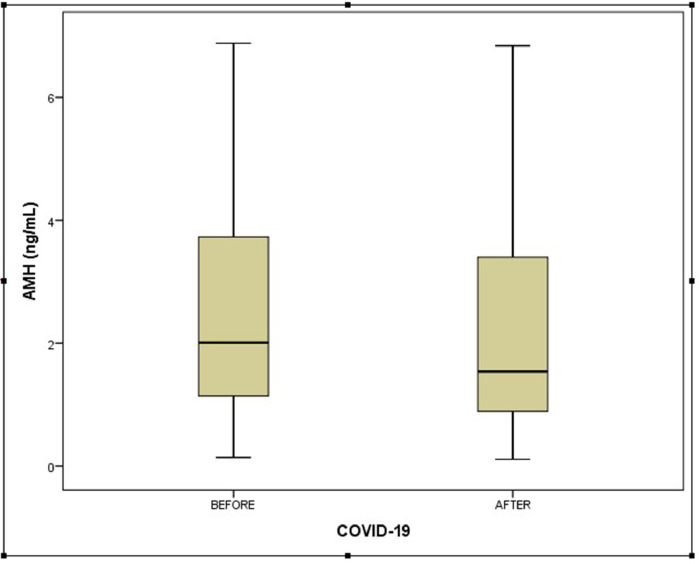

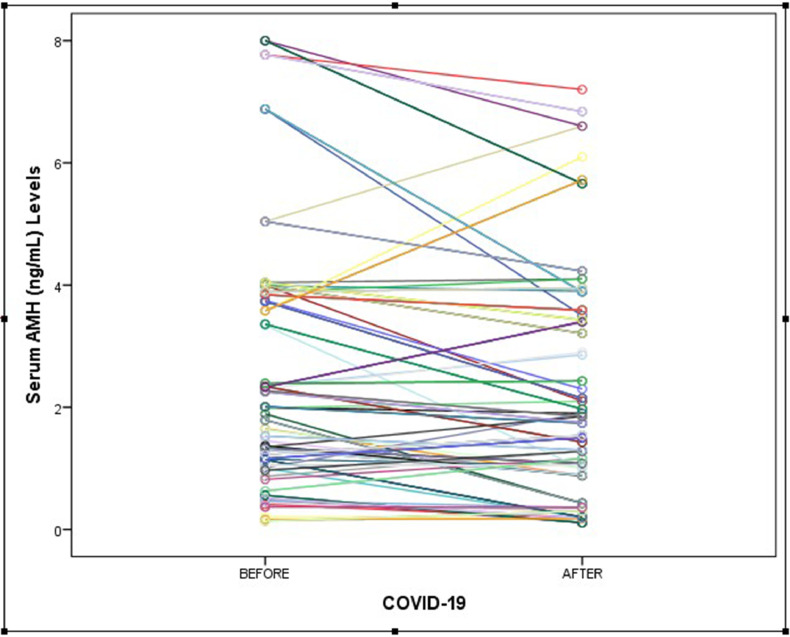

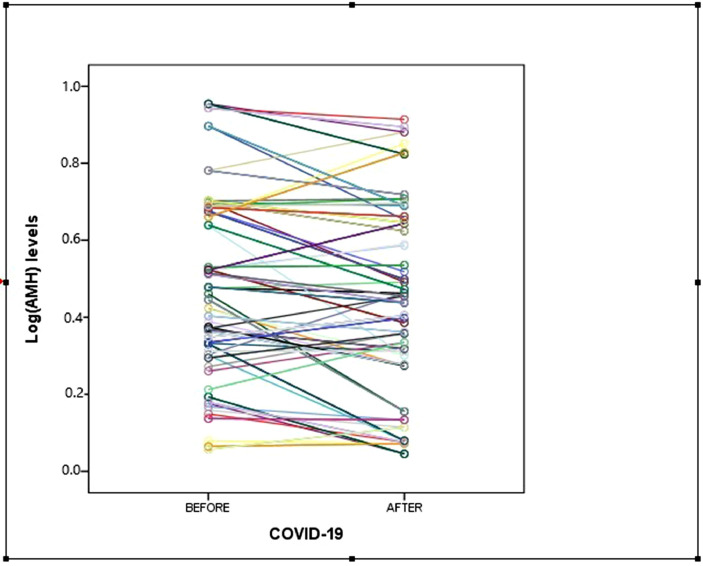

The serum AMH concentrations were compared between groups and are shown in Figures 1 and 2 . The median serum AMH concentration in participants before COVID-19 disease was 2.01 ng/ml (IQR 1.09–3.78 ng/ml) and the median serum AMH concentration in participants after COVID-19 disease was 1.74 ng/ml (IQR 0.88–3.41 ng/ml). This difference was statistically non-significant (P = 0.097). The log-transformed value of AMH and log(AMH) is also presented as an outcome variable and compared between groups (see Table 2 and Figure 3 ). In the early follicular phase of the study patients in the pre-COVID-19 period, FSH, LH, oestradiol reproductive function tests were compared with the post-COVID-19 period and are presented in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of serum concentrations of FSH, LH or oestradiol between pre- and post-illness (P = 0.118, 0.201, 0.181, respectively). Additionally, the ratio of FSH/LH was similar in both groups (1.42 versus 1.61, P = 0.268).

Figure 1.

Box plot of the mean ± SD serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) concentrations of participants both before and after COVID-19 disease.

Figure 2.

Serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) concentration differences between pre- and post-COVID-19 measurements.

Figure 3.

Log(anti-Müllerian hormone [AMH]) concentration differences between pre- and post-COVID-19 measurements.

Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has still continued to infect people all over the world and there are hundreds of thousands of clinical studies on COVID-19 disease, but it is still unclear whether COVID-19 affects female reproductive function. Therefore, the results of the present study will make an important contribution to reducing fear and anxiety. According to these study results, COVID-19 disease does not appear to damage the ovarian reserve. However, some AMH concentrations decreased quite quickly; this may be caused by severe oophoritis or multisystem inflammatory syndrome due to COVID-19.

It is known that the most sensitive and earliest ovarian reserve biomarker is AMH (Tal and Seifer, 2017). In this study, there was no significant difference in serum AMH concentrations of the patients in the pre-COVID-19 period compared with the post-COVID-19 period. In a similar study, Li et al. (2021) reported that COVID-19 illness did not change serum AMH concentrations among the study groups. They compared 91 women with COVID-19 of reproductive age to 91 healthy women, and also reported that there was no significant difference in sex hormone concentrations such as FSH, LH, oestradiol, progesterone and testosterone among the study groups. Therefore they claimed that the SARS-CoV-2 virus did not affect ovarian reserve or sex hormone concentrations. In the same way, in this study, serum FSH, LH, FSH/LH ratio and oestradiol concentrations of the patients before COVID-19 illness were similar to the serum concentrations of the same patients after COVID-19 illness.

On the contrary, Ding et al. (2021b) reported that serum AMH concentrations of patients (n = 78) with COVID-19 (17 of them with severe illness) were significantly lower than serum AMH concentrations of healthy women (n = 51); hence, they claimed that the SARS-CoV-2 virus had a potentially harmful impact on ovarian reserve and endocrine function. They postulated that the SARS-CoV-2 virus enters into the cells owing to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (Hoffmann et al., 2020). In a previous animal study, it was reported that ovarian granulosa cells have ACE2 expression (Honorato-Sampaio et al., 2012); hence, the SARS-CoV-2 virus could attack and injure the ovary and reduce ovarian reserve. According to the current study, if this hypothesis was valid, a significant proportion of these study patients in post-COVID-19 illness would have had lower serum AMH concentrations. Therefore, this hypothesis cannot be accepted. This difference can be explained by the comparison of different groups, the different study methodology, the small number of subjects, and due to the high rate of severe COVID-19 disease in their study population (17/78) (Ding et al., 2021b).

In addition, recent studies have reported that low serum AMH concentrations were associated with psychological stress and severity of anxiety (Yeğin et al., 2021). Menstruation, which is arranged by the HPO axis, may be easily disrupted by psychological stress, infectious disease, drugs and organ dysfunctions (Kala and Nivsarkar, 2016; Yeğin et al., 2021). Appropriately, the current study found that the number of women with irregular menstruation and amenorrhoea slightly increased after COVID-19 illness; however, the study patients had a significant reduction in menstrual volume during the 3 months following illness. Nevertheless, almost all menstrual changes resolved within 3 months after the illness. In another study investigating the effect of COVID-19 on menstrual status, it was reported that menstrual volume decreased, the duration of menstrual cycles was prolonged, and amenorrhoea increased (Ding et al., 2021b; Li et al., 2021). Additionally, in the present study, spontaneous pregnancy was observed in 15/147 participants (10.2%) after COVID-19 illness.

The limitations of other similar studies were taken into account and this study was designed accordingly. The aim was to evaluate ovarian reserve after recovery; hence, serum sex hormone concentrations were measured at least 3 months after recovery from COVID-19 illness. This is thought to be the first study to investigate the effect of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on ovarian reserve, because the methodology of this study was designed to be quasi-experimental. This means that the ovarian reserve of women before COVID-19 disease is compared with the ovarian reserve of the same women after COVID-19 disease. Also, this is a unique cohort, which included women within a narrow age range with two AMH measurements, pre- and post-COVID. There are several limitations to the study. First, there were only 3 out of 132 women with severe COVID-19 disease due to the study population including young women; therefore, comparisons between severe and non-severe illness groups could not be performed. It was not possible to find enough patients with severe disease, because non-menopausal women had slight severity and had better outcomes in terms of COVID-19 infection than menopausal women. Second, the limited sample size may not be sufficient for a powerful statistical analysis. Third, this study was done in a single centre. Fourth, because there were no serum progesterone, testosterone or prolactin concentrations of all the study patients before COVID-19 illness in the hospital databank, it could not be evaluated in this study. Fifth, to evaluate the long-term effect of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, it should be reassessed. If possible, autopsy or biopsy samples from the ovary should be evaluated to investigate the presence and long-term harm of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the ovary. Further research is needed.

According to the current study results and recent studies investigating the effect of COVID-19 on ovarian reserve, it can be suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 virus does not affect ovarian reserve; however, menstrual status changes may be related to extreme immune response and inflammation, or psychological stress and anxiety due to the COVID-19 disease. These menstrual status changes are also not permanent and resolve within a few months following COVID-19 illness. In addition, although menstrual irregularity was detected in more participants after COVID-19 disease, changes in the menstrual cycle were not statistically significant in the current results.

Biography

Dr Ilknur Col Madendag is a Gynaecologist at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Health Sciences University, Kayseri Medical Faculty City Hospital, Turkey. Her research focuses on ovarian endocrinology and infertility.

Key message.

Ovarian reserve of women before COVID-19 disease was compared with ovarian reserve of the same women after COVID-19 disease. This was a unique cohort, which included women within a narrow age range with two AMH measurements pre- and post-COVID. The SARS-CoV-2 virus does not impact on ovarian reserve.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Declaration: The authors report no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding T., Wang T., Zhang J., Cui P., Chen Z., Zhou S., Yuan S., Ma W., Zhang M., Rong Y., Chang J., Miao X., Ma X., Wang S. Analysis of ovarian injury associated with COVID-19 disease in reproductive-aged women in Wuhan, China: an observational study. Front Med. 2021;8:286–297. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.635255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T., Zhang J., Wang T., Cui P., Chen Z., Jiang J., Zhou S., Dai J., Wang B., Yuan S., Ma W., Ma L., Rong Y., Chang J., Miao X., Ma X., Wang S. Potential influence of menstrual status and sex hormones on female severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a cross-sectional multicenter study in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;72:e240–e248. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Kruger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T., Herrler G., Wu N., Nitsche A., Müller M., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honorato-Sampaio K., Pereira V.M., Santos R.A., Reis A.M. Evidence that angiotensin-(1–7) is an intermediate of gonadotrophin-induced oocyte maturation in the rat preovulatory follicle. Exp. Physiol. 2012;97:642–650. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.061960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase A., Nakamura T., Osuka S., Takikawa S., Goto M., Kikkawa F. Anti-Müllerian hormone as a marker of ovarian reserve: what have we learned, and what should we know? Reprod. Med. Biol. 2015;15:127–136. doi: 10.1007/s12522-015-0227-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kala M., Nivsarkar M. Role of cortisol and superoxide dismutase in psychological stress induced anovulation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2016;225:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Marca A., Broekmans F.J., Volpe A., Fauser B.C., Macklon N.S. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH): what do we still need to know? Hum. Reprod. 2009;24:2264–2275. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Chen G., Hou H., Liao Q., Chen J., Bai H., Lee S., Wang C., Li H., Cheng L., Ai J. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2021;42:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis G.M., Lum K.J., Sundaram R., Chen Z., Kim S., Lynch C.D., Schisterman E.F., Pyper C. Stress reduces conception probabilities across the fertile window: evidence in support of relaxation. Fertil. Steril. 2011;95:2184–2189. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metlay J.P., Waterer G.W., Long A.C., Anzueto A., Brozek J., Crothers K., Cooley L.A., Dean N.C., Fine M.J., Flanders S.A., Griffin M.R. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolhuijsen L.M., Visser J.A. Anti-Müllerian hormone and ovarian reserve: update on assessing ovarian function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105:3361–3373. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney K.L., Domar A.D. The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018;20:41–47. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/klrooney. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R., Seifer D.B. Ovarian reserve testing: a user's guide. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;217:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeğin G.F., Desdicioğlu R., Seçen E.İ., Aydın S., Bal C., Göka E., Keskin H.L. Low anti-Mullerian hormone levels are associated with the severity of anxiety experienced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod. Sci. 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021-00643-x. Jun 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]