CKD is increasing in incidence and prevalence globally and in low- and low-middle income countries.1 This is a result of the increasing prevalence of the major causes of CKD, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic glomerulonephritis, and poor identification and management of acute kidney injury (AKI) in low-resource settings. Chronic infections, such as HIV, hepatitis B and C, and the rampant use of herbal medications in low-income settings, also contribute significantly to CKD prevalence. Unfortunately, although there are efforts to increase the public awareness of some non-communicable diseases, there is less discussion on CKD prevention globally and in lower middle-income countries, hence CKD is described as the “neglected” non-communicable disease.2 There are very few public health programs to improve kidney health globally and especially in low-income settings.

In low-resource settings, primary health care providers poorly identify and manage patients with CKD or its risk factors in most situations. There is also poor identification and suboptimum management of AKI, which leads to late referral for nephrologist care associated with high mortality. Late presentation is also a result of low socio-cultural factors and poor economic conditions in low-income settings.3 The late presentation of kidney disease may also be a result of reduced health literacy of the populace, resorting to alternative health care, including the use of herbal medications, which may potentially cause AKI and lead to rapid progression to kidney failure.4

There are 0.31 nephrologists per million population in low-income settings compared with 28.5 nephrologist per million population in high-income countries.5 This limited nephrology workforce leads to suboptimum management of kidney diseases in most low-income settings and may lead to less public health interventions in the prevention and management of kidney diseases. Nonetheless, through task-shifting, the few nephrologists can educate primary care physicians on the prevention and optimum management of AKI and CKD. The active involvement of primary care physicians is vital in awareness creation, screening, early detection, and retarding CKD progress as they are more likely to see these patients in the early stages of CKD.6

In low-income settings, raising awareness, screening, and prevention of CKD have been shown to be effective in improving the incidence of kidney failure as the awareness of kidney disease and its risk factors is low among the general public.7 Health care professionals must leave the comfort of their wards, consulting rooms, and dialysis units to engage with the general public and communities to raise awareness, screen, and help prevent CKD. Targeted screening and early identification of CKD are therefore imperative in a low-resource setting.

The International Society of Nephrology, through the World Kidney Day (WKD) initiative, promotes kidney health education and help create awareness to prevent CKD. Local societies and organized groups in many countries take advantage of the yearly WKD activities to promote kidney health through awareness programs, and free screening exercises for diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease. As laudable as these events are, there is the need to organize them more frequently if we are to reach every corner with the message of kidney disease prevention in low-income settings. Furthermore, language used in these health promotion activities should be simple, clear, and with locally-tailored infographics for kidney health promotion.

Non-governmental organizations and local foundations in low-income settings, like the kidneyhealthinternational.org in Ghana, plan programs during the World Diabetes Day, World Hypertension Day, and WKD to augment the effort of the local society, Ghana Kidney Association, to educate the populace all year round. The Kidney Health International was founded by Dr. Elliot Koranteng Tannor, an International Society of Nephrology fellow, after his nephrology training in South Africa. On his return, he noted the gross lack of awareness of kidney disease in Ghana which may have accounted for the late presentation of patients with kidney failure in over 70% of cases. This was associated with increased in-hospital mortality of up to 50% of renal admissions in a 10-year retrospective study in a teaching hospital in Ghana.8 The cost of dialysis is beyond the reach of the average Ghanaian as the National Health Insurance Scheme does not pay for chronic and acute dialysis services in Ghana. Since its inception in 2016, the Kidney Health International has organized free health screening for over 3000 people and awareness programs reaching millions in rural and urban communities in Ghana. We screen for kidney disease and its risk factors, such diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. We also take advantage of world health days to educate the populace on kidney disease and its risk factors.

During the World Hypertension Day, we supported the International Society of Hypertension in screening 6907 people in the Ghana for hypertension in 2018 and 7102 people in 2019 in the May Measurement Month campaigns.9 We recruited and trained about 300 volunteers in the Ashanti region of Ghana to support this global campaign. We have visited over 50 churches, mosques, and corporate groups to educate on kidney health promotion. We have also visited over 20 radio stations and 9 television stations to reach millions of Ghanaians, educating them on kidney disease prevention in English and their local dialects.

In March 2021, the Kidney Health International dedicated the whole month for kidney health awareness in support of the WKD. We dubbed the campaign “Healthy Kidney Month,” where we trained and sent out 126 volunteers to engage in their communities throughout the month of March on kidney health. The volunteers visited churches and many organized groups to educate on kidney disease prevention. Daily kidney disease prevention tips were also shared on all our social media platforms. Social media has proven to be a reliable tool in disseminating kidney health information to the target audience with access to the internet. The Ghana Kidney Association during WKD rotate from one region to another, organizing public lectures, awareness creation, and free health screenings.

During the World Diabetes Day on November 14, 2021, the Kidney Health International celebrated the event with the rural community in Ghana where over 300 participants were screened for diabetes, hypertension, albuminuria, and obesity with 20 volunteers, including doctors and nurses (Figures 1 and 2). We also educated the members of the community on diabetes as a major risk factor for kidney disease. Those found to have diabetes, hypertension, or kidney disease were referred to see their local health care provider for continuing care.

Figure 1.

Some excited volunteers after a successful awareness and screening exercise in a rural community.

Figure 2.

Screening for diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease during a rural community outreach.

To task-shift and build the capacity of primary health care providers, we have set up kidney disease management teams in 6 community hospitals in Ghana and continually give support to these health care providers to optimize the prevention and management of AKI and CKD. The primary health care workers were trained to opportunistically screen patients at risk when they report to the hospital and use of reno-protective medications to retard the progression of CKD. In addition, early or prompt nephrology referral may lead to good outcomes in patients with CKD to prevent or delay the onset of kidney failure.

The major challenge for such free screening programs and awareness creation campaigns is funding and time constraints. It is imperative that such foundations and non-governmental organizations are funded to promote kidney health at every opportunity in their various communities in low-income settings with the help of locally trained volunteers in these communities. Community engagement with the involvement of local partners in low-income settings makes education and behavior change efforts more acceptable. We are grateful to the individuals, pharmaceutical companies, and corporates who have supported our efforts and the numerous volunteers who dedicated their time selflessly for our campaigns. Local nephrology societies can also source funds from philanthropic individuals, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and corporate organizations. Community engagement, awareness creation, and screening efforts must be sustainable to make the desired impact in these communities. Innovative methods of teaching in the community using language that the populace can easily understand, and training community health care workers to consolidate the knowledge regularly may be necessary.

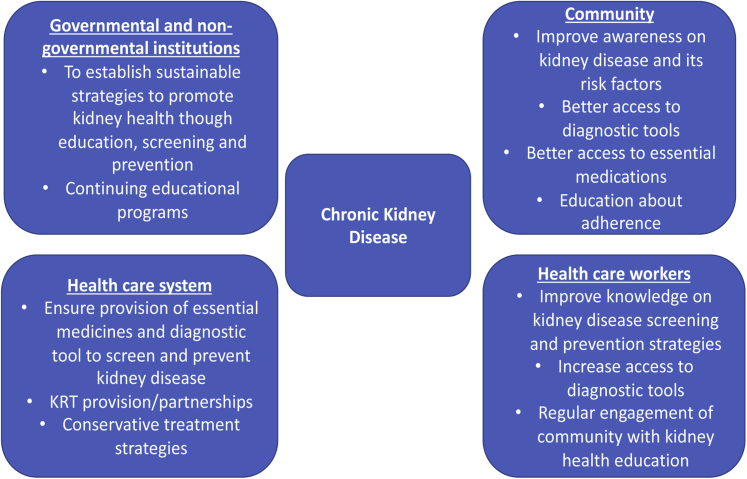

Training in preventive medicine should be prioritized and extended beyond physicians to other health care workers, such as community health workers, community health assistants, pharmacists, and nurses through task-shifting. The health care workforce should be provided with relevant knowledge and adequate skills to identify and treat AKI and CKD in community- and hospital-based settings. The introduction of kidney disease prevention into the curriculum at a basic level may stimulate a change in building an infrastructure that will improve awareness, access to care, diagnostic capacity, and delivery of care. Governmental and nongovernmental institutions, health care systems, health care workers, and the community have a part to play to ensure kidney health reaches all5 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Main fields that strategies could be applied to improve chronic kidney disease protection, prevention and management in low-income settings.5 KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

In conclusion, because of the high cost of managing kidney failure in low-income settings, there is the need to prioritize and optimize the prevention, early detection, and optimum management of kidney disease to delay the need for kidney replacement therapy in low-income settings. We cannot wait any longer for someone else to do this for us. With the little resource available in low-income settings, we have to think of cost-effective ways to improve kidney health for all. Implementing interventions that seek to engage the entire community workforce for equitable and quality care delivery with an emphasis on developing strategies to ensure better CKD awareness and detection is key. The goal should be to build a new generation of primary care physicians and health care workers who are well equipped to use affordable and preventive care strategies to tackle the growing epidemic of CKD. This can be channeled into effective, sustainable kidney health promotion programs without waiting for WKD annually. We are all involved in ensuring kidney health for all, irrespective of income or geographic status.

References

- 1.Stanifer J.W., Muiru A., Jafar T.H., Patel U.D. Chronic kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:868–874. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tannor E.K. Chronic kidney disease-the’neglected’non-communicable disease in Ghana. Afr J Curr Med Res. 2018;2:1. doi: 10.31191/afrijcmr.v2i1.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marie Patrice H., Joiven N., Hermine F., Jean Yves B., Folefack François K., Enow Gloria A. Factors associated with late presentation of patients with chronic kidney disease in nephrology consultation in Cameroon-a descriptive cross-sectional study. Ren Fail. 2019;41:384–392. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2019.1595644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha V., Rathi M. Natural medicines causing acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osman M.A., Alrukhaimi M., Ashuntantang G.E., et al. Global nephrology workforce: gaps and opportunities toward a sustainable kidney care system. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2018;8:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhowmik D., Pandav C.S., Tiwari S.C. Public health strategies to stem the tide of chronic kidney disease in India. Indian J Public Health. 2008;52:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiao L.L. Raising awareness, screening and prevention of chronic kidney disease: it takes more than a village. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018;23(suppl 4):107–111. doi: 10.1111/nep.13459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tannor E.K., Adusei K., Norman B.R. A 10-year retrospective review of renal cases seen in a Tertiary Hospital in West Africa. Afr J Curr Med Res. 2018;2:2. doi: 10.31191/afrijcmr.v2i2.24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twumasi-Ankrah B., Myers-Hansen G.A., Adu-Boakye Y., et al. May Measurement Month 2018: an analysis of blood pressure screening results from Ghana. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2020;22(suppl H):H59–H61. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]