Introduction

The burden of kidney disease has been growing steadily throughout the world. It is estimated that around 2 million patients, most of whom live in low and lower-middle income countries, reach end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) annually, and this is anticipated to worsen in the coming years.1, 2, 3 Kidney replacement therapy (KRT) requires highly technical equipment and expertise, which are costly. As a consequence, KRT is very unevenly distributed worldwide.4 The management of undocumented immigrants suffering from ESKD without medical insurance raises complex medical, social, financial, and ethical questions in countries with ample healthcare resources. As highlighted in recent studies, emergency-based, as opposed to scheduled dialysis, is associated with higher morbidity and mortality.5,6 Like other European countries, France has recently experienced an influx of immigrants, necessitating novel data on this issue. The French health care scheme provides for full reimbursement of ESKD-related expenditure based on citizenship and resident status.7 The lack of unambiguous national policies regarding insurance cover during the first 3 months of an undocumented migrant’s stay has given rise to disparate appraisal across nephrology centers in France: some centers provide emergency-only dialysis, while others offer scheduled hemodialysis.

We retrospectively collected demographic, medical, and social data from immigrant patients with no health insurance who needed urgent hemodialysis during a 1-year period in 2 academic hospitals in Paris, which, owing to their location in the northern periphery of Paris, have a history of providing medical care to migrant populations.

For methods, see Supplementary Methods.

Results

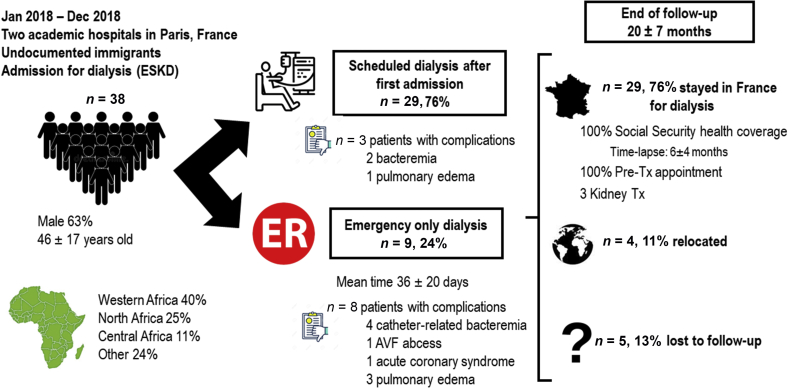

From January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2018, we retrospectively analyzed data from 38 patients (17 and 21 in Tenon and Bichat hospitals, respectively) and their initial clinical and demographic characteristics. These data are summarized in Table 1. A total of 63% were male; median age was 46 ± 17 years. Most patients (n = 22, 58%) had never received chronic hemodialysis before their arrival in France. The median stay in France before being diagnosed with ESKD was 169 days [68; 3162] for these 22 patients. The main regions of origin were Western Africa (n = 15, 39%), North Africa (n = 10, 26%), and Central Africa (n = 4, 11%). Of 38 patients, 6 had received at least 1 hemodialysis session in other EU states (Italy n = 2; Spain n =2; The Netherlands n = 1; United Kingdom n = 1) and 3 in other French cities before arriving in Paris. Cause of kidney disease was undetermined in 50% of cases. Table 1 shows patients’ comorbidities, including hypertension (n = 14, 37%), diabetes mellitus (n = 8, 21%), ischemic cardiomyopathy (n = 5, 13%), hepatitis B virus infection (n = 4, 11%), and HIV infection (n = 3, 8%). Among the 17 patients who settled in France with a previously created arteriovenous fistula (AVF), 3 required the implantation of a central venous catheter for dialysis because of nonfunctional vascular access. Most patients (n = 29, 76%) were enrolled in a scheduled dialysis program either from the outset or after the first admission to a critical care unit. If the patient was not enlisted on the scheduled hemodialysis program after initial hospitalization, the mean wait time on emergency-only hemodialysis was 36 ± 20 days. In 9 of such patients, all but 1 patient (n = 8, 88.9%) presented a total of 9 severe complications, including 4 catheter-related bloodstream bacteremia, 1 AVF abscess, 1 acute coronary syndrome, and 3 acute pulmonary edema. Of the patients directly enrolled on a scheduled dialysis program, 3 patients (10.3%) presented severe complications (2 bacteremia and 1 pulmonary edema [P < 0.001]). The complications were recorded within 2 months after first hospitalization. There were no deaths during the study period, but 9 patients were lost to follow-up or had relocated, so subsequent health status was unknown.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, geographic origins, and follow-up of patients

| Clinical characteristics | Variable |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 46 ± 17 |

| Male | 63 (24) |

| Chronic dialysis history | 42 (16) |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 45 (17) |

| Dialysis catheter | 13 (5) |

| Hypertension | 37 (14) |

| Diabetes | 21 (8) |

| Tuberculosis | 3 (1) |

| Drepanocytosis | 3 (1) |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 13 (5) |

| HIV infection | 8 (3) |

| HBV infection | 11 (4) |

| Bilharziosis | 3 (1) |

| Cirrhosis | 3 (1) |

| Stroke | 5 (2) |

| Kidney disease | |

| Undetermined | 50 (19) |

| PKD | 8 (3) |

| Obstructive | 8 (3) |

| Diabetic | 21 (8) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 11 (4) |

| Other | 8 (3) |

| Geographic origin | |

| West Africa | 39 (15) |

| Central Africa | 11 (4) |

| North Africa | 26 (10) |

| Other | 24 (9) |

| Status at the end of follow-up | |

| Dialysis in France | 68 (26) |

| Kidney Tx in France | 8 (3) |

| Lost to follow-up | 13 (5) |

| Relocation | 11 (4) |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; PKD, polycystic kidney disease Tx, transplantation.

Values expressed as percentage (n) or mean ± SD.

At the end of the follow-up (mean 20 ± 6.7 months), 76% of the patients (n = 29) were enrolled in a scheduled dialysis program or were transplanted in France. Five were lost to follow-up, and 4 relocated to another country. Of the 26 patients on chronic dialysis in France at the end of follow-up, 6 were still being treated in the public hospital dialysis center, while 20 had transferred to private centers for self-care dialysis, standard medical dialysis, or in-center hemodialysis. One patient chose public hospital peritoneal dialysis. Three patients underwent kidney transplantation.

In 26 of the 38 cases, we were able to ascertain the delay with which state-funded medical care insurance (SMC) was granted. Undocumented immigrants are entitled to SMC, provided that they have been living on national territory for over 3 months without legal rights or financial assets. Practically speaking, the average time lapse between initial presentation and SMC grant was 189 ± 126 days, mainly owing to administrative delays. Access to SMC was not regarded an administrative prerequisite for patients to be offered AVF in either the Tenon or Bichat institution. In fact, all but 2 patients had an AVF created before procurement of SMC (the mean delay between first hospitalization and AVF creation was 105 ± 48 days). All patients who ultimately established residency in France were accorded a pretransplant appointment during follow-up once they secured SMC. The overall results are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study results overview. AVF, arteriovenous fistula, ER, emergency room; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease, Tx, transplantation.

Discussion

Undocumented migrant patients suffering from ESKD experience an unacceptably high rate of complications when not enlisted on a scheduled dialysis program after initial hospitalization compared with undocumented patients allocated scheduled dialysis. A few patients were transiently treated on an emergency-only dialysis scheme both because of congested public dialysis units and the inaccessibility of private facilities for which SMC is a compulsory condition. After initial in-hospital dialysis center management, access to less cumbersome and cheaper programs of self-care dialysis was hindered by a delayed agreement for medical insurance.

As they were not originally systematically captured, it was difficult to determine the reasons why immigrants relocated to France. However, we found that 44% of migrant patients with ESKD had received nephrological care before their relocation, suggesting an interruption to medical management because of financial problems. Accordingly, a public and private dialysis network is slowly emerging, and most states fund at least part of the health costs; advance expenses incurred by patients’ prior state financial support curtail the significance of such programs.

All but 1 patient on scheduled dialysis (n = 8 of 9, 88.9%) had dialysis-related complications, although severe complications affected only 10.3% of patients on scheduled dialysis in the 2 months after first hospitalization. These results are in keeping with North American data from Cervantes et al.,5,8 which found emergency-only hemodialysis to be associated with an unacceptable and dramatic increase of morbidity in these patients. Social precariousness and unsanitary living conditions (4 of the 21 patients from the Bichat hospital cohort were homeless) may also potentiate the risk of infectious complications, especially, vascular access-related bacteremia. Programmed thrice-weekly dialysis sessions may help control this risk through repeated and consistent skin and device care. Transition from emergency-based dialysis to scheduled dialysis is also followed by significant improvement on all 5 Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36-Item Short Form Survey subscales, as demonstrated by a previous study.9

The average time to obtain SMC insurance was 6 ± 4 months. Once patients have secured medical state funding, they become eligible for private hemodialysis, so it is important to develop regulatory policies that can expedite this transfer to prevent public hospital hemodialysis from becoming overwhelmed. Our study does not provide detailed economic data, but it has been previously demonstrated that on top of an increased rate of complications, the emergency-only dialysis strategy increases costs owing to the expense of multiple hospitalizations in intensive care units.5 On initial management, these patients exhibit a range of different complications arising from several days or more of KRT discontinuation (or delayed initiation), including fluid overload, anemia, and AVF-related problems, all of which could have potentially been avoided by scheduled appointments. As a result, transient management in a critical care setting may be required during the initial management stage. The majority of dialysis cases in critical care were solely prompted by KRT sessions, adding to an already overburdened care service. Excluding the initial hospitalization, and considering the entire cohort, the emergency-only dialysis scheme resulted in 74 hospitalizations in intensive care units. Bearing in mind that a 24-hour hospital stay in intensive care (about €2000/d in Paris public hospitals) equates with 8 hemodialysis sessions in a self-care dialysis center (about €250/session), prioritizing dialysis management in these facilities would offer substantial savings.

In addition, the average age of our patients was 46 years, compared with 70 years, the median age of hemodialysis initiation in France according to the French registry REIN 2019.10 Bar the initial management stage, younger and more autonomous patients are potentially better suited to less costly programs such as self-care dialysis. Our study corroborates this view because 53% of the patients on KRT will eventually continue with dialysis as self-care or in a medical dialysis unit.

As an emergency-only dialysis strategy is associated with a high complications rate and elevated costs in this particular ESKD population, inclusive organizational measures should be developed so that undocumented migrant patients can access scheduled dialysis programs.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Diane Alves and Maureen Pouilloux, social workers in Tenon Hospital, for their help managing this patient cohort. The authors also want to thank the Emergency Department in Tenon Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods.

References

- 1.Liyanage T., Ninomiya T., Jha V., et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385:1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamgboye E.L. End-stage renal disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(suppl 2):S2–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naicker S. End-stage renal disease in sub-Saharan and South Africa. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;(83):S119–S122. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doreille A., Godefroy R., Martzloff J., et al. French nationwide survey of undocumented end-stage renal disease migrant patient access to scheduled haemodialysis and kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:393–395. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervantes L., Tuot D., Raghavan R., et al. Association of emergency-only vs standard hemodialysis with mortality and health care use among undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:188–195. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen O.K., Vazquez M.A., Charles L., et al. Association of Scheduled vs emergency-only dialysis with health outcomes and costs in undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:175–183. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefebvre O., Maille D. [Access to rights, access to care: what obstacles for migrants?] Rev Prat. 2019;69:567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervantes L., Fischer S., Berlinger N., et al. The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:529–535. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cervantes L., Tong A., Camacho C., Collings A., Powe N.R. Patient-reported outcomes and experiences in the transition of undocumented patients from emergency to scheduled hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2021;99:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.REIN (Réseau Epidémiologie, Information, Néphrologie) Rapport annuel 2019. Accessed December 31, 2021. https://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_rein_2019_2021-10-14.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.