Abstract

Despite our close genetic relationship with chimpanzees, there are notable differences between chimpanzee and human social behavior. Oxytocin and vasopressin are neuropeptides involved in regulating social behavior across vertebrate taxa, including pair bonding, social communication, and aggression, yet little is known about the neuroanatomy of these systems in primates, particularly in great apes. Here, we used receptor autoradiography to localize oxytocin and vasopressin V1a receptors, OXTR and AVPR1a respectively, in seven chimpanzee brains. OXTR binding was detected in the lateral septum, hypothalamus, medial amygdala, and substantia nigra. AVPR1a binding was observed in the cortex, lateral septum, hypothalamus, mammillary body, entire amygdala, hilus of the dentate gyrus, and substantia nigra. Chimpanzee OXTR/AVPR1a receptor distribution is compared to previous studies in several other primate species. One notable difference is the lack of OXTR in reward regions such as the ventral pallidum and nucleus accumbens in chimpanzees, whereas OXTR is found in these regions in humans. Our results suggest that in chimpanzees, like in most other anthropoid primates studied to date, OXTR has a more restricted distribution than AVPR1a, while in humans the reverse pattern has been reported. Altogether, our study provides a neuroanatomical basis for understanding the function of the oxytocin and vasopressin systems in chimpanzees.

Keywords: Lateral septum, Amygdala, Ventral pallidum, Social behavior, Great apes, Primate, OXTR, AVPR1a

Introduction

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), along with their sister species, bonobos (P. paniscus), are our closest living relatives (Prüfer et al. 2012). Accordingly, we share many features of social behavior, yet differ in key ways as well. Like humans, chimpanzees form strong social bonds, and show cooperation even among non-kin, particularly in hunting or defense contexts (Langergraber et al. 2007, 2009; Mitani 2009). However, humans often form pair bonds between mates, while chimpanzees mate promiscuously and opportunistically, though there may be some stable male–female relationships (Langergraber et al. 2013). Moreover, unlike humans, chimpanzees rarely engage in paternal care (Lehmann et al. 2006), though they may protect against infanticide (Murray et al. 2016). Finally, lethal aggression is common among chimpanzees, both within (Gilby et al. 2013; Pusey et al. 2008) and between groups (Wilson et al. 2014). Human groups also engage in lethal intergroup aggression, though there is great variability between societies based on subsistence mode, population density, economic defensibility of resources, and other influences (Dyson-Hudson and Alden Smith 1978; Fry and Soderberg 2013; Kaplan et al. 2009).

The proximate mechanisms of these social behavioral differences are not well understood. One promising line of research for understanding the neural basis of social behavior has involved the neuropeptides oxytocin (OXT) and vasopressin (AVP). These neuropeptides, and their non-mammalian analogues, regulate social behavior across a wide range of vertebrate taxa (Donaldson and Young 2008). Produced by separate cells in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, OXT and AVP have physiological effects on labor, lactation, water balance, and vasoconstriction when released from the pituitary into the bloodstream (Burbach et al. 2006; Knepper et al. 2015). OXT and AVP are also released within the brain, where they modulate social behavior (Grinevich et al. 2016; Ross and Young 2009; Johnson and Young 2017). In rodents, OXT regulates social recognition, pair-bonding, and maternal caregiving (Walum and Young 2018; Rilling and Young 2014; Johnson and Young 2017). OXT is thought to modulate complex social behavior by enhancing the salience and reinforcing value of social stimuli (Young 2015; Walum and Young 2018; Froemke and Young 2021). OXT is generally anxiolytic (Waldherr and Neumann 2007), and it has been associated with cooperation and in-group altruism in humans (De Dreu 2012; Israel et al. 2012; Kosfeld et al. 2005; Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2011; Jurek and Neumann 2018) but see (Declerck et al. 2020). AVP is often anxiogenic, enhancing vigilance, and regulates aggressive and territorial behaviors (Gobrogge et al. 2009; Ferris et al. 1997; Goodson 2005; Albers 2012) but also pair bonding, paternal behavior, and mate guarding in males (Donaldson et al. 2010; Wang et al. 1994; Nair and Young 2006).

OXT and AVP exert their effects on behavior by binding to receptors distributed throughout the brain. A powerful example from vole research demonstrates that species-specific distributions of brain OXT and AVP (1a subtype) receptors, OXTR and AVPR1a, respectively, can contribute to species-typical social behaviors (Young 1999; Young and Zhang 2021). In monogamous prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster), OXTR density is high in several regions, including the prelimbic cortex, nucleus accumbens, and lateral amygdala, all of which show less or no OXTR binding in the polygynous montane vole (M. montanus) or meadow vole (M. pennsylvanicus). By contrast, in the polygynous species, OXTR are localized to the lateral septum, ventromedial hypothalamus, and cortical nucleus of the amygdala (Insel and Shapiro 1992). There are also species differences in AVPR1a distributions among these voles, with prairie voles having higher densities in the ventral pallidum (Insel et al. 1994; Lim et al. 2004b). OXTR in the nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex, and AVPR1a in the ventral pallidum and lateral septum regulate pair bonding in female and male prairie voles, respectively (Johnson and Young 2015; Lim et al. 2004b; Young and Wang 2004; Young et al. 2001). Receptor antagonists in these areas block partner-preference formation (Lim and Young 2004; Liu et al. 2001; Young et al. 2001), while manipulating receptor gene expression has the predicted effect on social behavior (Barrett et al. 2013; Lim and Young 2004; Keebaugh et al. 2015; Ross et al. 2009). Thus, the effects of OXT and AVP on social behavior are highly dependent on the distribution of their receptors. Further, individual variation in receptor densities contribute to individual variation in social behavior among prairie voles (Hammock and Young 2005; Okhovat et al. 2015; King et al. 2016).

There is some evidence linking OXT and AVP to the regulation of social behavior in chimpanzees as well. OXT may be involved in mediating cooperative relationships in these animals. In one study of wild chimpanzees, urinary OXT was higher in strongly socially bonded dyads (whether kin or non-kin) after a grooming interaction as compared with dyads without a strong social bond (Crockford et al. 2013). Urinary OXT is elevated in chimpanzees after a food sharing event in both the food donor and food receiver (Wittig et al. 2014). Urinary OXT in chimpanzees has also been associated with both the anticipation of and cohesion during intergroup conflict (Samuni et al. 2017), reconciliation after conflict (Preis et al. 2018), and coordinated hunting (Samuni et al. 2018). Thus, OXT may be acting in chimpanzees to strengthen and promote long-term social bonds as well as short-term social group cohesion, which may be a component of the coordination needed to defend against an outgroup.

While there are no studies connecting urinary AVP with chimpanzee behavior, AVPR1a gene (AVPR1A) polymorphisms are associated with chimpanzee cognition, behavior, and brain structure. In contrast to humans and bonobos, chimpanzees are polymorphic for a deletion of 360 base pairs in the promoter region of AVPR1A (± DupB), which contains a microsatellite, RS3 (Donaldson et al. 2008). In humans, a longer form of the RS3 microsatellite is associated with greater prosocial behavior (Knafo et al. 2008) and increased amygdala activation in face recognition (Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2009). The deletion of this DupB region in chimpanzees is associated with reduced sociality, particularly in males (Staes et al. 2014), as well as lower dominance and higher conscientiousness (Hopkins et al. 2012), and reduced performance on a task of joint attention (Hopkins et al. 2014) and mirror self-recognition (Mahovetz et al. 2016). Recently, DupB genotype in chimpanzees has been linked to gray matter covariation in several cortical regions (Mulholland et al. 2020).

A crucial step in disentangling the proximate mechanisms of chimpanzee social behavior is understanding where in the brain these neuropeptides act. A handful of studies have investigated the neuroanatomical distribution of OXTR and AVPR1a in primate species, revealing some unifying features as well as species differences. Here, we characterize the distribution of OXTR and AVPR1a in chimpanzee brains in a set of regions spanning from the nucleus accumbens through the posterior hippocampus and midbrain. We also place our results within the context of receptor binding studies from several other primates.

Materials and methods

Specimens

Blocks of fresh brain tissue from seven chimpanzees (six female, one male, ages 21–57.7 years) were recovered at necropsy and flash frozen opportunistically after natural death (PMI < 2.5 h). Brain blocks were obtained through the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource (NIH grant NS092988). Blocks were sectioned on a cryostat at 20 μm thickness, placed onto 2 × 3 inch Adhesion Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Brain Research Laboratories, Cambridge, MA), and stored in a freezer at − 80 °C. All tissues were collected in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines for the humane care and use of experimental animals. Our tissue samples included a selection of brain regions in coronal slices, from the most anterior part of the caudate nucleus rostrally through the mammillary body and hippocampus caudally, with two chimpanzees having additional sections further back through the anterior midbrain tegmentum and pons. Our samples thus did not include the frontal pole, occipital cortex, midbrain tectum, or any parts of the brainstem caudal to the midbrain tectum.

Receptor autoradiography

For receptor autoradiography, slides were thawed in racks at RT for 1 h and placed in a vacuum desiccator for 1 h. Slides were dipped for 2 min in 0.1% paraformaldehyde in 7.4 pH phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and rinsed in 50 mM Tris buffer to remove endogenous ligand. To reveal OXTR binding, adjacent sections were placed in one of three conditions, adapted from Freeman et al. (2014a): 1) 50 pM 125I-ornithine vasotocin analog (125I-OVTA, Catalogue #NEX254010UC, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) alone, 2) 50 pM 125I-OVTA plus 1 nM unlabeled AVPR1a-selective compound SR49059 (Catalogue # 2310, Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN), or 3) 125I-OVTA plus 1 nM SR49059 plus 50 nM unlabeled OXTR-selective agonist [Thr4, Gly7]OT (TGOT) (Peninsula Laboratories, Belmont, CA). To reveal AVPR1a binding, adjacent sections were placed in one of two conditions, following Young et al. (1999): (1) 50 pM 125I-Linear V1a antagonist (125I-LVA, Phenylacetyl1, 0-Me-D-Tyr2, [125I-Arg6]-) (Catalogue #NEX310050UC, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), or (2) 50 pM 125I-LVA plus 50 nM unlabeled Manning compound (d(CH2)5[Tyr(Me)2]AVP, Catalogue # 3377, Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN). Binding chambers were designed in Tinkercad and 3D printed in resin; files are freely available for download online at http://oxytocin.emory.edu/outreach/autoradiography-binding-chambers.html. After ligand incubation, sections were washed in 50 mM Tris buffer plus 2% MgCl2, pH 7.4 to remove excess radioligand, and dipped in deionized water and air-dried. Slides were exposed to BioMax MR film for 6, 14, or 21 days (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Images were obtained from the films using a light box and adjusted for equal brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). All images presented in this manuscript were developed for 14 days.

Acetylcholinesterase staining

Sections previously used for receptor autoradiography were stained for acetylcholinesterase to provide an anatomical guide (Lim et al. 2004a). Slides were placed in a solution of ethopropazine, glycine, cupric sulfate, acetylthiocholine iodide, and sodium acetate for 6 h. Next, they were rinsed in deionized water and then placed in sodium sulfide solution for 30 min. Sections were rinsed in water again and then exposed to silver nitrate for intensification for 10 min. Slides were air dried overnight and cover-slipped. Acetylcholinesterase stains were compared to both human (Ding et al. 2016) and rhesus macaque atlases (Paxinos et al. 2000) to define anatomical boundaries.

Results

Radioligand specificity

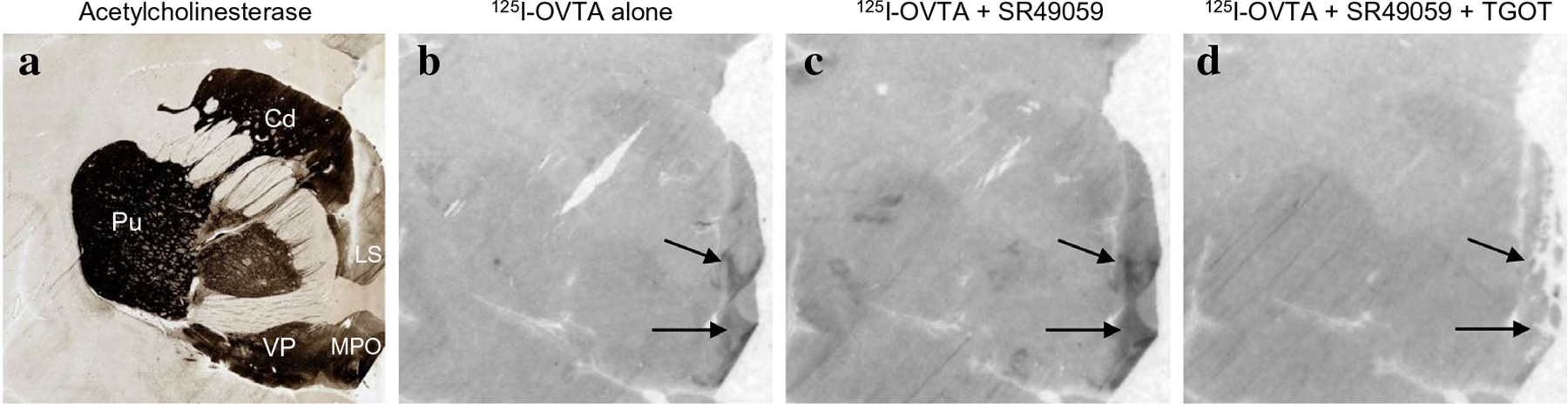

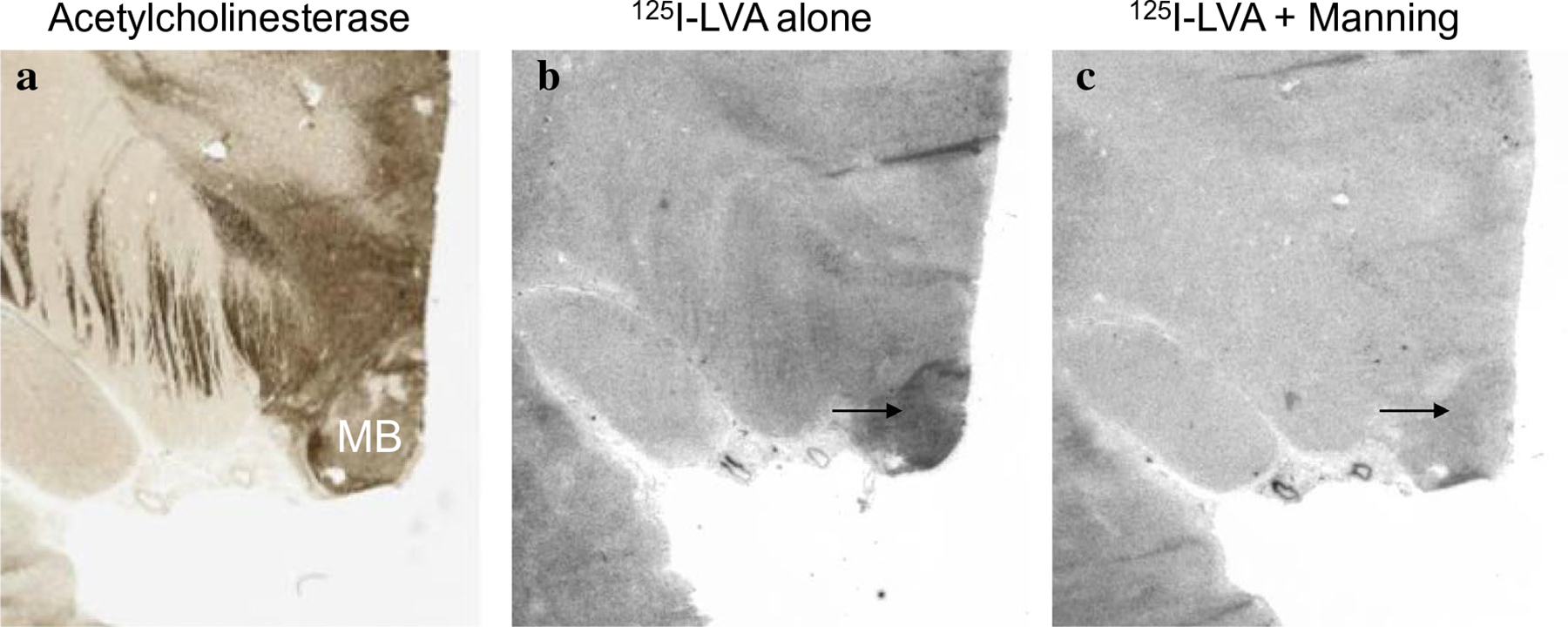

To ensure selectivity of radioligand binding, we incubated sections either with radioligand alone or with some combination of unlabeled competitor. For OXTR autoradiography, the selective AVPR1a compound, SR49059, did not noticeably affect radioligand binding, while [Thr4, Gly7]OT eliminated binding, indicating that 125I-OVTA was indeed binding to OXTR and not AVPR1a (Fig. 1). For AVPR1a autoradiography, the Manning compound reduced binding (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

125I-OVTA binding with and without competitors. a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b 125I-OVTA alone produces binding in the LS and MPO. c 125I-OVTA plus SR49059, an unlabeled vasopressin antagonist, produces binding in the LS and MPO. d 125I-OVTA plus SR49059 plus unlabeled oxytocin antagonist drastically reduces binding. Cd caudate, Pu Putamen, LS lateral septum, MPO medial preoptic area, VP ventral pallidum

Fig. 2.

125I-LVA binding with and without competitors. a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b 125I-LVA alone produces dense binding in the MB. c 125I-LVA plus the Manning compound reduces binding in the MB. MB mammillary body

Neuroanatomical distribution of 125I-OVTA binding to reveal OXTR

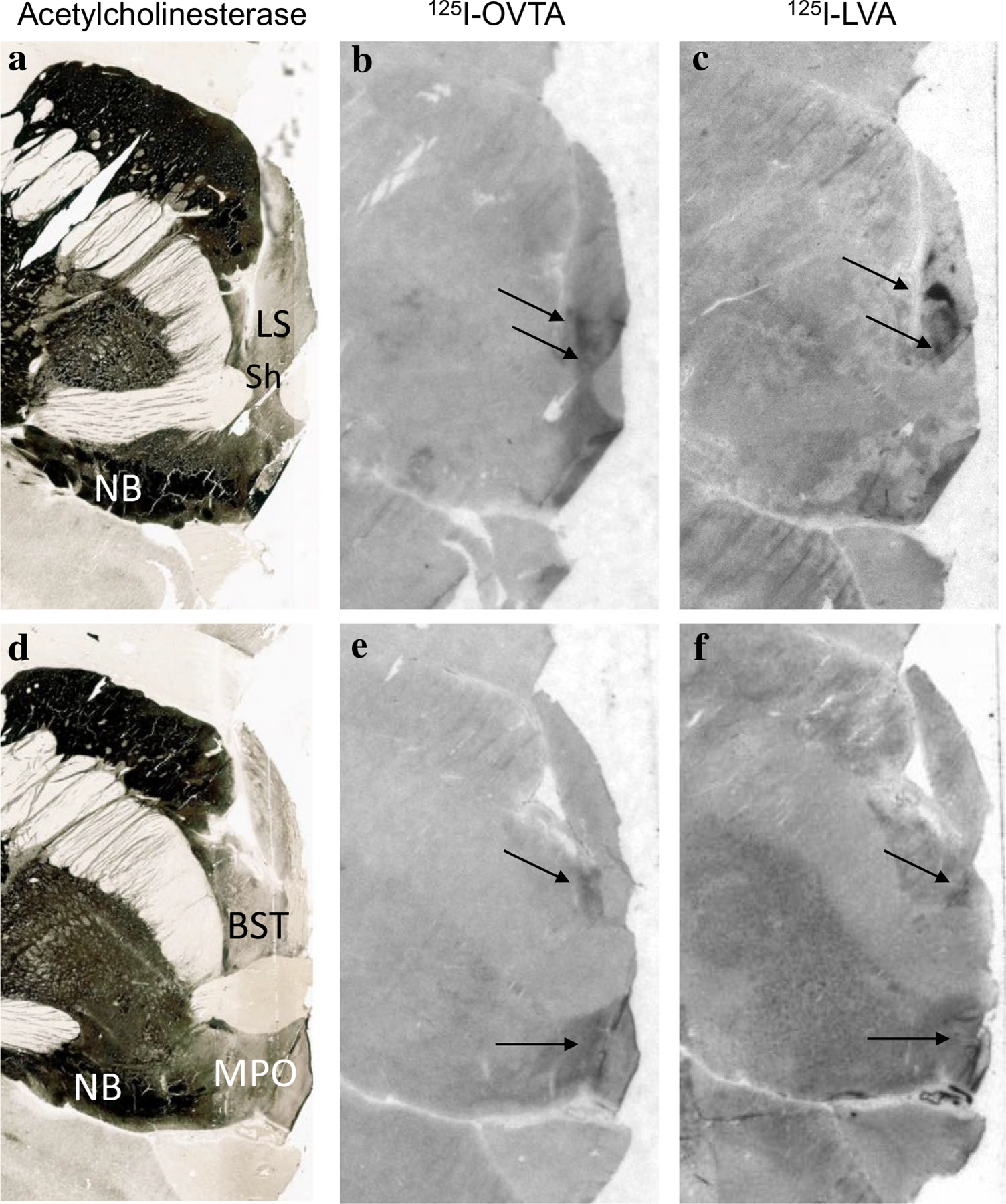

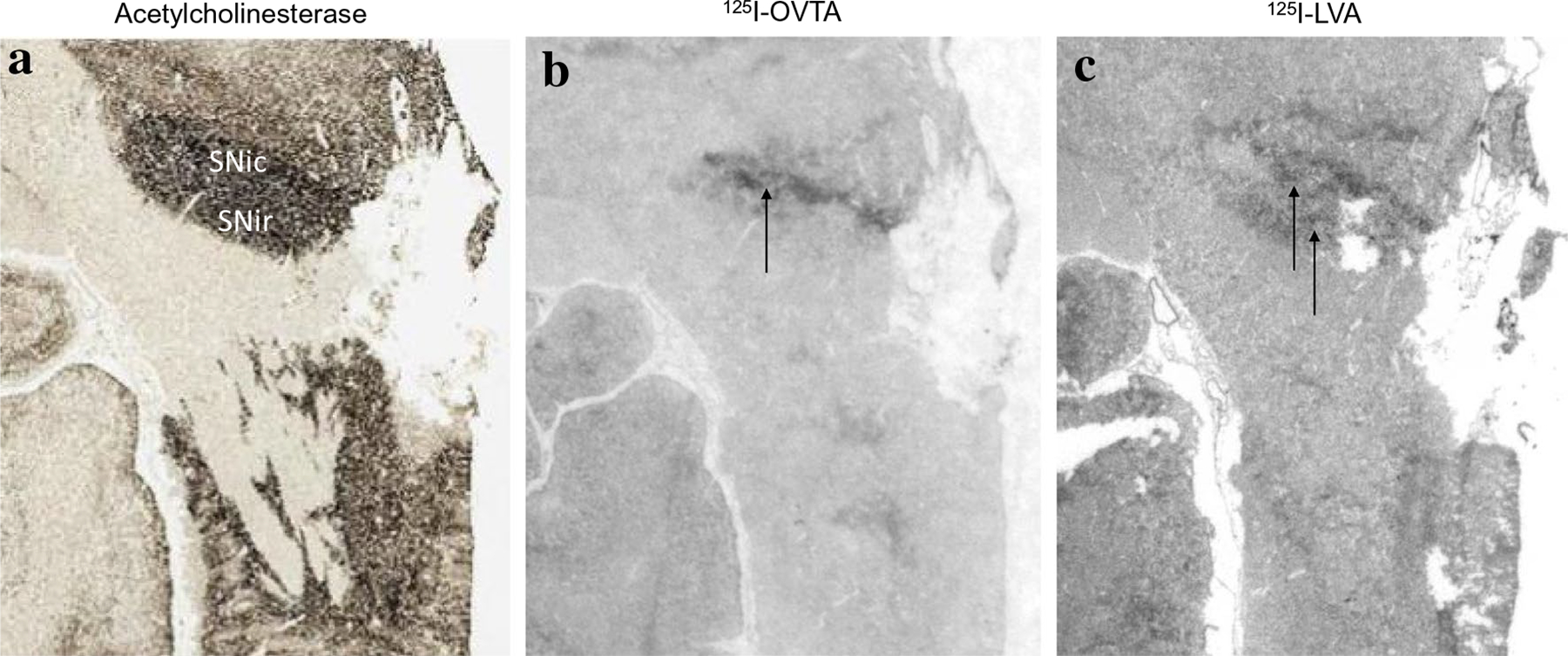

In chimpanzees, similar to other non-human primates, the distribution of 125I-OVTA binding was relatively limited when compared to 125I-LVA, suggesting OXTR has a more restricted distribution than AVPR1a in these animals. Dense 125I-OVTA signal was detected in the ventral lateral septum and septohypothalamic nucleus (Fig. 3), diagonal band of Broca and in several regions of the hypothalamus, including the medial preoptic area (Fig. 3), supraoptic nucleus, and paraventricular nucleus. In the midbrain, dense 125I-OVTA binding was observed in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Fig. 4). Moderate 125I-OVTA binding was found in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST) (Fig. 3), zona incerta and medial amygdala (Fig. 5). 125I-OVTA binding above background was not observed in the entorhinal and perirhinal cortex (Fig. 6), anterior cingulate cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann’s area 8). Notably, 125I-OVTA binding was not observed in the ventral pallidum, in contrast to results from human brains (Freeman et al. 2018; Loup et al. 1991). 125I-OVTA binding was not observed in other nuclei of the amygdala, such as the central amygdala and basolateral nuclear group. No 125I-OVTA binding was detected in the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 7) or the hippocampus (Fig. 6). A summary of 125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in chimpanzees and a comparison to reports from other primates can be found in Fig. 8.

Fig. 3.

125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in the lateral septum (LS) and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST). a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b OXTR binding (125I-OVTA plus SR49059 vasopressin antagonist) in the ventral lateral septum and septohypothalamic nucleus. c AVPR1a binding (125I-LVA alone) in the ventral lateral septum and septohypothalamic nucleus. d Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. e OXTR binding (125I-OVTA plus SR49059 vasopressin antagonist) in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial preoptic area (MPO). f AVPR1a binding (125I-LVA alone) in the BST and MPO. LS lateral septum, MPO medial preoptic area, NB nucleus basalis of Meynert, Sh septohypothalamic nucleus

Fig. 4.

125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in the substantia nigra (SNi). a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b OXTR binding (125I-OVTA plus SR49059 vasopressin antagonist) in the substantia nigra pars compacta. c AVPR1a binding (125I-LVA alone) in the substantia nigra pars compacta and pars reticulata. SNic substantiana nigra pars compacta, SNir substantia nigra pars reticulata

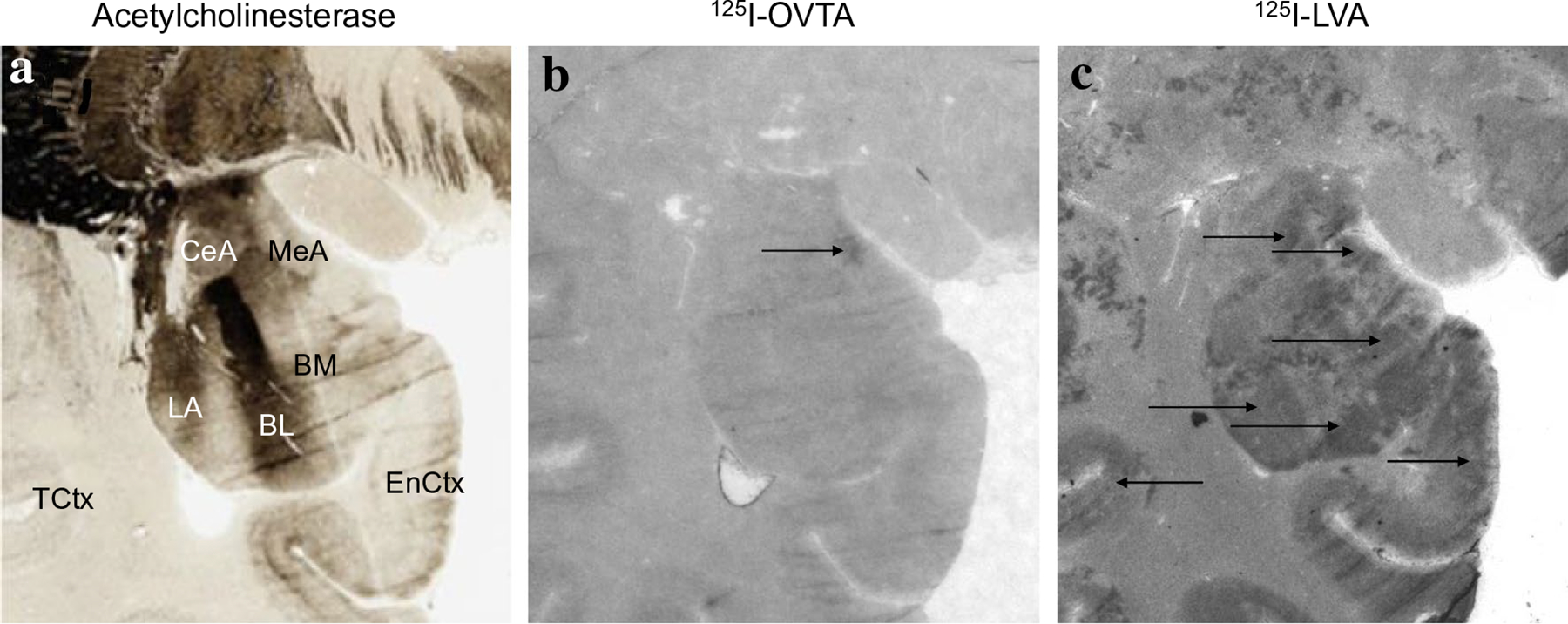

Fig. 5.

125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in the amygdala. a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b OXTR binding (125I-OVTA plus SR49059 vasopressin antagonist) in the medial amygdala. c AVPR1a binding (125I-LVA alone) in the basolateral nuclei of the amygdala, as well as entorhinal cortex. MeA medial amygdala, CeA central amygdala, LA lateral nucleus of amygdala, BL basoltaeral nucleus of amygdala, BM basomedial nucleus of amygdala, EnCtx entorhinal cortex, TCtx temporal cortex

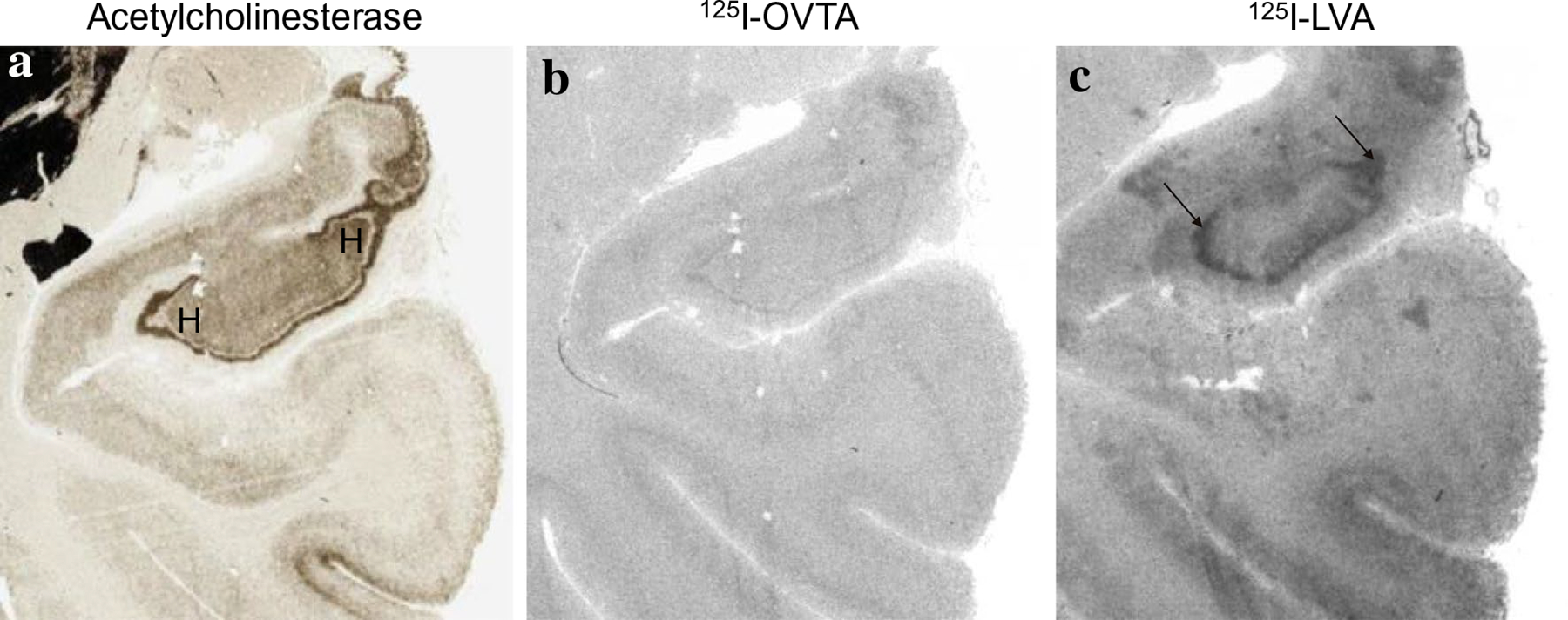

Fig. 6.

125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in the hilus of the hippocampus. a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b OXTR binding (125I-OVTA plus SR49059 vasopressin antagonist) above background was not detected in the hilus of the hippocampus. c Dense AVPR1a (125I-LVA alone) in the hilus of the hippocampus. H hilus

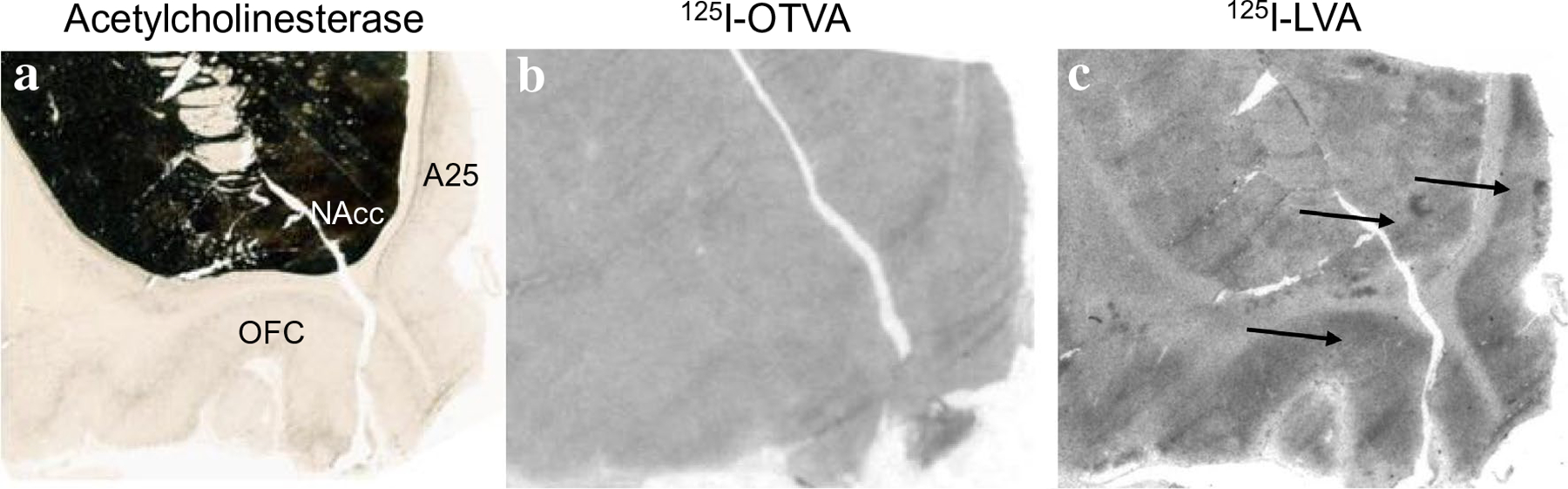

Fig. 7.

125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in the nucleus accumbens. a Acetylcholinesterase stain for anatomical guide. b OXTR (125I-OVTA plus SR49059 vasopressin antagonist) above background was not detected in the nucleus accumbens. c AVPR1a (125I-LVA alone) in the nucleus accumbens, orbitofrontal cortex, and subcallosal division of the anterior cingulate cortex (Brodmann’s area 25). NAcc nucleus accumbens, OFC orbitofrontal cortex, A25 Brodmann’s area 25

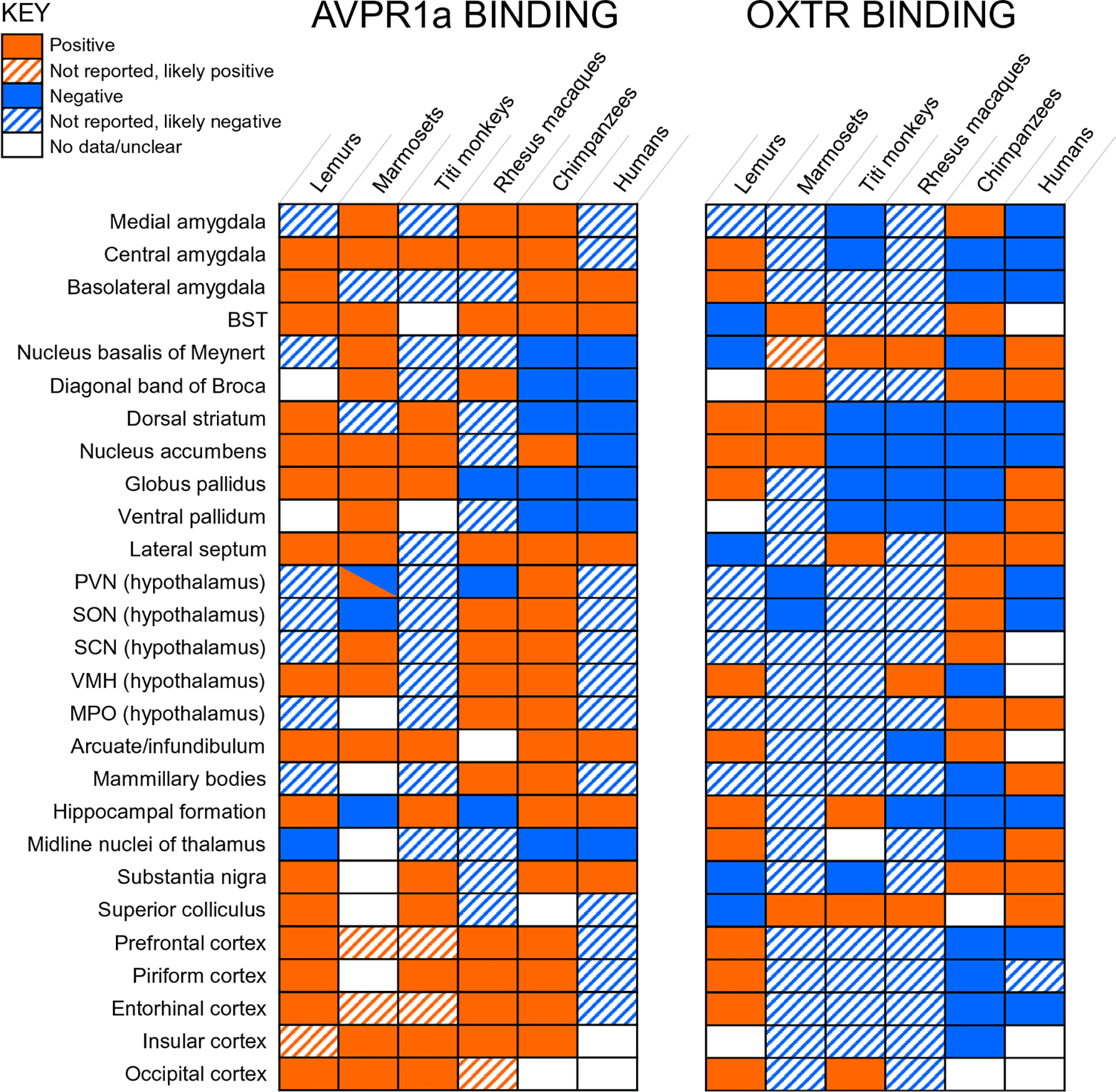

Fig. 8.

Comparison of OXTR and AVPR1a binding across primates studied to date. OXTR and AVPR1a binding has been reported in lemurs (Grebe et al. 2021), marmosets (Schorscher-Petcu et al. 2009; Wang et al. 1997), titi monkeys (Freeman et al. 2014b), rhesus macaques (Young et al. 1999; Freeman et al. 2014a), chimpanzees (current study) and humans (Loup et al. 1991, 1989; Freeman et al. 2018, 2016). BST bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, PVN paraventricular nucleus, SON supraoptic nucleus, SCN suprachiasmatic nucleus, VMH ventromedial hypothalamus, MPO medial preoptic area. Regions denoted as “positive” or “negative” were explicitly mentioned in an article, while “likely positive” regions typically had images with binding but were not explicitly discussed. “Likely negative” regions had images that showed an absence of binding but were not explicitly discussed. For “no data/unclear”, regions were either not included in the study, not shown, or presence/absence of binding could not be confidently inferred from images. Note that while OXTR receptor binding has not been detected in the nucleus accumbens in humans (Loup et al. 1991), OXTR mRNA has been detected in this region (Bethlehem et al. 2017; Quintana et al. 2019)

Neuroanatomical distribution of 125I-LVA binding to reveal AVPR1a

Dense 125I-LVA binding was found in the cortex, particularly the entorhinal, perirhinal, and insular cortex (Figs. 5, 6). Moderate 125I-LVA binding was also observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in Brodmann’s area 8, orbitofrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex (Fig. 7). Dense 125I-LVA binding was observed in the ventral lateral septum and septohypothalamic nucleus (Fig. 3) as well as the mammillary body (Fig. 2). Moderate 125I-LVA binding was found in the medial preoptic area, supraoptic nucleus, and paraventricular nucleus as well as the substantia nigra pars reticulata and pars compacta (Fig. 4). Moderate 125I-LVA binding was detected in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Moderate 125I-LVA binding was also found in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Light 125I-LVA binding in all amygdalar nuclei (Fig. 5), including the central and medial amygdalar nuclei as well as the basolateral complex, whereas OXTR binding was only found in the medial amygdaloid nucleus. Light binding was also found in the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 7). Finally, dense 125I-LVA binding was observed in the hilar region of the hippocampus (Fig. 6) but was not found in other regions of the hippocampus such as the CA fields and granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus.

Discussion

In the present study, we characterized the distribution of 125I-OVTA binding for OXTR and 125I-LVA binding for AVPR1a in seven chimpanzee brains using receptor autoradiography. We place our findings in the context of those from other primates; importantly, a degree of ambiguity is inherent in making comparisons from results across laboratories with different tissue quality and experimental protocols. Ideally, additional studies will investigate gene expression to validate the results for receptor autoradiography across primates.

We observed 125I-OVTA binding for OXTR mainly in the lateral septum, diagonal band of Broca, hypothalamus, zona incerta, and medial amygdala. For AVPR1a, we observed 125I-LVA binding in several cortical regions, the lateral septum, hypothalamus, hippocampus, substantia nigra, BST, and amygdala. Overall, the distribution of OXTR appeared to be more restricted than that of AVPR1a in chimpanzees, a pattern also observed in most other anthropoid primates studied (Fig. 8). Interestingly, humans differ from this pattern, with OXTR being more widely distributed than AVPR1a in human brains (Loup et al. 1991). In lemurs, the pattern of OXTR and AVPR1a is largely similar (Grebe et al. 2021). A major contributor to this balance is the presence of AVPR1a in the cortex of most primate species studied (Fig. 8). Along with the cortex, the most consistent regions with AVPR1a binding across primates are the amygdala, BST, and lateral septum. OXTR results across primates are more varied, with the most common positive results found in the nucleus basalis of Meynert and the superior colliculus (Fig. 8).

One interesting difference between chimpanzees and humans is seen in the expression of OXTR in the ventral pallidum and nucleus accumbens. We did not detect OXTR radioligand binding in these regions in chimpanzees, while humans express OXTR in the ventral pallidum as detected by receptor autoradiography (Loup et al. 1991; Freeman et al. 2018) and OXTR mRNA has been detected in the nucleus accumbens (Bethlehem et al. 2017; Quintana et al. 2019). The expression of OXTR and AVPR1a in the reward system has been implicated in pair bonding behavior in rodents (Johnson and Young 2015) and this mechanism could promote pair bonding in primates as well. AVPR1a is densely expressed in the ventral pallidum and OXTR in the nucleus accumbens of monogamous marmosets (Wang et al. 1997; Schorscher-Petcu et al. 2009). Furthermore, AVPR1a is densely expressed in the nucleus accumbens of monogamous titi monkeys (Freeman et al. 2014b). Neither AVPR1a or OXTR are expressed in the ventral pallidum or nucleus accumbens of non-monogamous rhesus macaques (Freeman et al. 2014a; Young et al. 1999). Thus, in pair bonding primates that have been studied, either the nucleus accumbens or ventral pallidum express OXTR or AVPR1a. Notably, however, a recent comparison of OXTR and AVPR1a binding in monogamous and non-monogamous lemur species did not detect a difference in these reward-related areas (Grebe et al. 2021), suggesting that the biological basis of pair-bonding may not be the same in all primate taxa. Nevertheless, it is possible the expression of OXTR in these regions could be involved in the greater pair bonding behavior and social monogamy in humans compared to our chimpanzee relatives. Future research could compare the receptor distribution patterns in other ape species, such as bonobos which mate promiscuously (de Waal and Lanting 1997) and gibbons which form strong pair bonds and have low sexual dimorphism (Palombit 1994).

AVPR1a and OXTR binding were also observed in the amygdala in chimpanzees. This was more widespread for AVPR1a than OXTR. Light AVPR1a binding was found across the entire amygdala in chimpanzees, whereas OXTR binding was highly restricted to the medial amygdala, at the border with the posterior cortical nucleus. Evidence from receptor autoradiography suggests there is AVPR1a binding in the basal nucleus of the amygdala and no OXTR binding in the amygdala of humans (Loup et al. 1991). AVPR1a binding in the amygdala, particularly the central nucleus, is present in most primate species studied (Fig. 8). Further research is needed to determine if there are true differences in neuropeptide receptor distribution in the amygdala between humans and chimpanzees. Moreover, it would be interesting to compare chimpanzee and bonobo receptor distribution in the amygdala, given the fact that bonobos are closely related to chimpanzees but much lower in aggression and higher in tolerance of strangers (Hare et al. 2012). The amygdala participates in brain circuits that direct attention to the eyes (Adolphs 2010) and recent evidence suggests that OXT may increase eye contact in bonobos but not chimpanzees (Brooks et al. 2020). However, patterns of social attention in these species may depend on other contextual factors such as sex-based dominance hierarchies (Lewis et al. 2021); future work connecting OXT to social attention should take these factors into account. Theories of human and bonobo social-behavioral evolution have proposed parallel changes in the OXT system via self-domestication (Hare 2017). Interestingly, a recent analysis investigating the evolutionary history of the OXTR gene in the human and Pan lineages found evidence of homologous evolution in humans and bonobos in two variants outside the coding region for OXTR, while humans and chimpanzees shared one variant (Staes et al. 2021). One of these, the A allele of OXTR rs237897 shared between bonobos and humans, is linked in increased male prosociality, while OXTR rs2228485(A) shared between chimpanzees and humans is linked to better reading of male facial expressions. The involvement of OXT and AVP in the species-specific social behavior of chimpanzees and bonobos presents a fascinating avenue for future work.

We previously reported OXT and AVP immunoreactive axonal fibers in chimpanzee cortex (Rogers et al. 2018). AVP-immunoreactive fibers were detected in the cingulate cortex, insula, and olfactory cortex, while OXT-immunoreactive fibers were detected in the straight gyrus and cingulate cortex in chimpanzees. Accordingly, in this study we found widespread AVPR1a binding in the cortex, including the cingulate cortex, insula, and olfactory cortex, as well as entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, and frontal cortex. However, we did not detect significant OXTR binding in frontal, cingulate, entorhinal, and perirhinal cortex. We did not have sections rostral enough to examine the straight gyrus for OXTR in chimpanzees. The presence of AVPR1a in these regions provides further evidence that cortical areas important for many “higher” aspects of social cognition such as empathy (e.g., insula and anterior cingulate cortex) are sensitive to OXT and AVP in great apes. Previous studies in humans (Loup et al. 1991) did not focus on OXTR or AVPR1a distribution in the cortex. Because OXT- and AVP-immunoreactive fibers were found in the same cortical areas in humans, with AVP fibers additionally in the dysgranular insula in humans, future research can determine if these cortical areas have a similar pattern of OXTR and AVPR1a in humans as in chimpanzees.

Unlike in other anthropoid primates, we did not find clear evidence of OXTR binding in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, an area important for visual attention, in chimpanzees. A recent study in lemurs also reported no OXTR binding in this region (Grebe et al. 2021) (Fig. 3). The superior colliculus also has shown OXTR binding in several primate species (Fig. 8); however, our tissue samples did not include this region. It is possible that OXTR does indeed mediate this cognitive function across primates but accomplishes this through different neurobiological mechanisms in different branches of the primate order.

There are some limitations to our study. We did not examine all brain regions but rather a selection of tissue from the most anterior part of the basal ganglia through the substantia nigra. Future research is needed to determine the extent of OXTR and AVPR1a binding in the brainstem of chimpanzees. Several other primate species examined (humans, titi monkeys, marmosets, rhesus macaques) have OXTR binding in the spinal trigeminal nucleus and superior colliculus, thought to be related to visual attention to social stimuli (Freeman and Young 2016; Freeman et al. 2014a, b, 2016; Schorscher-Petcu et al. 2009). Future studies with tissue samples from these regions will determine if chimpanzees have OXTR binding in these areas, as expected. Additionally, humans have AVPR1a binding in the nucleus prepositus of the brainstem, important for eye gaze stabilization (Freeman et al. 2016). Given that humans are especially reliant on eye gaze as social cues (Tomasello et al. 2007), it would be interesting to determine whether chimpanzees and humans differ in the distribution of AVPR1a in this region. Also, six of the seven chimpanzee brains examined for OXTR and AVPR1a in this study were female. While we did not observe any obvious differences in the one male chimpanzee, a more systematic approach to sampling is needed to assess whether there are sex differences in receptor distribution.

Additional limitations are related to the competitive binding strategy employed. The ligand 125I-OVTA binds promiscuously to OXTR and AVPR1a in rhesus macaques (Freeman et al. 2014a) but less so in titi monkeys (Freeman et al. 2014b). To minimize OVTA binding to AVPR1a, we co-incubated 125I-OVTA with unlabeled SR49059, which is selective for AVPR1a. To estimate non-specific binding, we also included 50 nM TGOT. This approach should allow us to identify 125I-OVTA binding to OXTR with confidence. More problematic is our strategy to demonstrate specificity of 125I-LVA binding. Selectivity was assessed using the Manning compound, which is highly selective for AVPR1a in rodents, but binds to human AVPR1a with only twice the affinity as OXTR. At the concentration used, 50 nM, it is likely that the Manning compound would displace LVA from both OXTR and AVPR1a. Competition with SR49059 would have been a more optimal strategy. Thus the competition alone does not demonstrate that 125I-LVA is only labeling AVPR1a and not OXTR. However, our strategy did reveal regions labeled by 125I-LVA but not 125I-OVTA, such as the cortex, and a region labeled by 125I-OVTA but not 125I-LVA, the diagonal band. Thus, while our competitive strategy was not ideal, we are confident that the combination of radioligands and competitors are revealing accurate and distinct representations of OXTR and AVPR1a distributions in chimpanzee brains. Further studies with in situ hybridization are needed to provide confirmation, particularly for regions with overlapping 125I-LVA and 125I-OVTA binding, such as the substantia nigra, and to determine if OXTR and AVPR1a are expressed in the same cells or in different cell populations. Importantly, in comparing our results to those from humans, it should be noted that Loup. et al. (1989; 1991) did not use a competitive binding strategy and thus radioligands in that study could have bound promiscuously to OXTR and AVPR1a; however, recent work using improved methods (Freeman et al. 2018) has upheld the presence of OXTR in the ventral pallidum in humans.

In addition to binding protocols used, another source of variation across the primate studies compared in Fig. 8 is the post-mortem interval. The chimpanzees in our study had PMI of less than 2.5 h, while the monkey and lemur studies were presumably shorter (promptly after veterinary euthanization) and the human studies were longer (< 24 h for Loup et al. 1991; < 33 h for Freeman et al. 2018). However, multiple analyses from human brains with a PMI range of 5–33 h found no association between post-mortem interval and optical binding density for these ligands, suggesting that the structure of OXTR and AVPR1a remain intact for extended periods of time after death, at least up to 33 h (Freeman et al. 2016, 2018).

In summary, we characterized the distribution of OXTR and AVPR1a binding in chimpanzees in several brain regions involved in social behavior. We compared these results to those from other primates. Overall, our findings suggest chimpanzees have similarities with most other non-human primates studied in that distribution of OXTR is more restricted than AVPR1a, while humans show the reverse pattern. Chimpanzees also do not appear to have dense OXTR in reward regions, while humans do. In contrast, chimpanzees have significant AVPR1A binding in the amygdala while humans do not. These contrasts provide hypotheses regarding the potential contribution of OXT and AVP to species differences in social behavior in chimpanzees and humans. Thus, this study provides foundational information about the neurobiology of the OXT/AVP system in chimpanzees, which contributes to our understanding of the proximate mechanisms of social behavior in these animals.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mar Sanchez and Marcelia Maddox for equipment training and usage.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from The Leakey Foundation (#38217) to CNRF, a pilot grant from the Center for Translational Social Neuroscience at Emory, NIH grants 1P50MH100023 to LJY, P51OD11132 to YNPRC, and NS092988 to the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Ethics approval This work was done using archival, opportunistically collected post-mortem brain tissue collected from subjects that died from natural causes following procedures approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines for the humane care and use of experimental animals. No living great apes were used in this study.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

- Adolphs R (2010) What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1191:42–61. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05445.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers HE (2012) The regulation of social recognition, social communication and aggression: vasopressin in the social behavior neural network. Horm Behav 61(3):283–292. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CE, Keebaugh AC, Ahern TH, Bass CE, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ (2013) Variation in vasopressin receptor (Avpr1a) expression creates diversity in behaviors related to monogamy in prairie voles. Horm Behav 63(3):518–526. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethlehem RAI, Lombardo MV, Lai MC, Auyeung B, Crockford SK, Deakin J, Soubramanian S, Sule A, Kundu P, Voon V, Baron-Cohen S (2017) Intranasal oxytocin enhances intrinsic corticostriatal functional connectivity in women. Transl Psychiatry 7(4):e1099. 10.1038/tp.2017.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks J, Kano F, Sato Y, Yeow H, Morimura N, Nagasawa M, Kikusui T, Yamamoto S (2020) Divergent effects of oxytocin on eye contact in bonobos and chimpanzees. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.105119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbach JP, Young LJ, Russell J (2006) Oxytocin: synthesis, secretion, and reproductive functions. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of [Google Scholar]

- Crockford C, Wittig RM, Langergraber K, Ziegler TE, Zuberbuhler K, Deschner T (2013) Urinary oxytocin and social bonding in related and unrelated wild chimpanzees. Proc Biol Sci 280(1755):20122765. 10.1098/rspb.2012.2765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CKW (2012) Oxytocin modulates cooperation within and competition between groups: An integrative review and research agenda. Horm Behav 61(3):419–428. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck CH, Boone C, Pauwels L, Vogt B, Fehr E (2020) A registered replication study on oxytocin and trust. Nat Hum Behav 4(6):646–655. 10.1038/s41562-020-0878-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding SL, Royall JJ, Sunkin SM, Ng L, Facer BA, Lesnar P, Lein ES (2016) Comprehensive cellular-resolution atlas of the adult human brain. J Comparative Neurol 524(16):3127–3481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson ZR, Young LJ (2008) Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality. Science 322(5903):900–904. 10.1126/science.1158668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson ZR, Kondrashov FA, Putnam A, Bai Y, Stoinski TL, Hammock EAD, Young LJ (2008) Evolution of a behavior-linked microsatellite-containing element in the 5’flanking region of the primate AVPR1A gene. BMC Evol Biol 8(1):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson ZR, Spiegel L, Young LJ (2010) Central vasopressin V1a receptor activation is independently necessary for both partner preference formation and expression in socially monogamous male prairie voles. Behav Neurosci 124(1):159–163. 10.1037/a0018094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson-Hudson R, Alden Smith E (1978) Human teritoriality: an ecological reassessment. Am Anthropol 80(1):21–41. 10.1525/aa.1978.80.1.02a00020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris CF, Melloni RH Jr, Koppel G, Perry KW, Fuller RW, Delville Y (1997) Vasopressin/serotonin interactions in the anterior hypothalamus control aggressive behavior in golden hamsters. J Neurosci 17(11):4331–4340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SM, Inoue K, Smith AL, Goodman MM, Young LJ (2014a) The neuroanatomical distribution of oxytocin receptor binding and mRNA in the male rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Psychoneuroendocrinology 45:128–141. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SM, Walum H, Inoue K, Smith AL, Goodman MM, Bales KL, Young LJ (2014b) Neuroanatomical distribution of oxytocin and vasopressin 1a receptors in the socially monogamous coppery titi monkey (Callicebus cupreus). Neuroscience 273:12–23. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.055.Neuroanatomical [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SM, Smith AL, Goodman MM, Bales KL (2016) Selective localization of oxytocin receptors and vasopressin 1a receptors in the human brainstem. Soc Neurosci 00(00):1–11. 10.1080/17470919.2016.1156570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SM, Palumbo MC, Lawrence RH, Smith AL, Goodman MM, Bales KL (2018) Effect of age and autism spectrum disorder on oxytocin receptor density in the human basal forebrain and midbrain. Transl Psychiatry 8(1):257. 10.1038/s41398-018-0315-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SM, Young LJ (2016) Comparative perspectives on oxytocin and vasopressin receptor research in rodents and primates: Translational implications. J Neuroendocrinol (5). 10.1111/jne.12382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froemke RC, Young LJ (2021) Oxytocin, neural plasticity, and social behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci 44:359–381. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-102320-102847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry DP, Soderberg P (2013) Lethal Aggression in Mobile Forager Bands and Implications for the Origins of War. Science 341(6143):270–273. 10.1126/science.1235675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilby IC, Brent LJN, Wroblewski EE, Rudicell RS, Hahn BH, Goodall J, Pusey AE (2013) Fitness benefits of coalitionary aggression in male chimpanzees. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 67(3):373–381. 10.1007/s00265-012-1457-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobrogge KL, Liu Y, Young LJ, Wang Z (2009) Anterior hypothalamic vasopressin regulates pair-bonding and drug-induced aggression in a monogamous rodent. PNAS 106(45):19144–19149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL (2005) The vertebrate social behavior network: evolutionary themes and variations. Horm Behav 48(1):11–22. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebe NM, Sharma A, Freeman SM, Palumbo MC, Patisaul HB, Bales KL, Drea CM (2021) Neural correlates of mating system diversity: oxytocin and vasopressin receptor distributions in monogamous and non-monogamous Eulemur. Sci Rep 11(1):3746. 10.1038/s41598-021-83342-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinevich V, Knobloch-Bollmann HS, Eliava M, Busnelli M, Chini B (2016) Assembling the Puzzle: Pathways of Oxytocin Signaling in the Brain. Biological Psychiatry 79 (3). doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock EAD, Young LJ (2005) Microsatellite instability generates diversity in brain and sociobehavioral traits. Science 308(5728):1630–1634. 10.1126/science.1111427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare B (2017) Survival of the friendliest: Homo sapiens evolved via selection for prosociality. Annu Rev Psychol 68:155–186. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare B, Wobber V, Wrangham R (2012) The self-domestication hypothesis: evolution of bonobo psychology is due to selection against aggression. Anim Behav 83(3):573–585. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Donaldson ZR, Young LJ (2012) A polymorphic indel containing the RS3 microsatellite in the 5′ flanking region of the vasopressin V1a receptor gene is associated with chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) personality. Genes Brain Behav 11(5):552–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Keebaugh AC, Reamer LA, Schaeffer J, Schapiro SJ, Young LJ (2014) Genetic influences on receptive joint attention in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Sci Rep 4:3774. 10.1038/srep03774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Shapiro LE (1992) Oxytocin receptor distribution reflects social organization in monogamous and polygamous voles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89(13):5981–5985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Wang ZX, Ferris CF (1994) Patterns of brain vasopressin receptor distribution associated with social organization in microtine rodents. J Neurosci 14(9):5381–5392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel S, Weisel O, Ebstein RP, Bornstein G (2012) Oxytocin, but not vasopressin, increases both parochial and universal altruism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37(8):1341–1344. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ZV, Young LJ (2015) Neurobiological mechanisms of social attachment and pair bonding. Curr Opin Behav Sci 3:38–44. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ZV, Young LJ (2017) Oxytocin and vasopressin neural networks: implications for social behavioral diversity and translational neuroscience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 76:87–98. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurek B, Neumann ID (2018) The oxytocin receptor: from intracellular signaling to behavior. Physiol Rev 98(3):1805–1908. 10.1152/physrev.00031.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HS, Hooper PL, Gurven M (2009) The evolutionary and ecological roots of human social organization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364(1533):3289–3299. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keebaugh AC, Barrett CE, Laprairie JL, Jenkins JJ, Young LJ (2015) RNAi knockdown of oxytocin receptor in the nucleus accumbens inhibits social attachment and parental care in monogamous female prairie voles. Soc Neurosci 10(5):561–570. 10.1080/17470919.2015.1040893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LB, Walum H, Inoue K, Eyrich NW, Young LJ (2016) Variation in the oxytocin receptor gene predicts brain region-specific expression and social attachment. Biol Psychiatry 80(2):160–169. 10.1016/jbiopsych.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafo A, Israel S, Darvasi A, Bachner-Melman R, Uzefovsky F, Cohen L, Feldman E, Lerer E, Laiba E, Raz Y, Others, (2008) Individual differences in allocation of funds in the dictator game associated with length of the arginine vasopressin 1a receptor RS3 promoter region and correlation between RS3 length and hippocampal mRNA. Genes Brain Behav 7(3):266–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knepper MA, Kwon T-H, Nielsen S (2015) Molecular physiology of water balance. N Engl J Med 372(14):1349–1358. 10.1056/NEJMra1404726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (2005) Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 435(7042):673–676. 10.1038/nature03701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber KE, Mitani JC, Vigilant L (2007) The limited impact of kinship on cooperation in wild chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(19):7786–7790. 10.1073/pnas.0611449104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber K, Mitani J, Vigilant L (2009) Kinship and social bonds in female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am J Primatol 71(10):840–851. 10.1002/ajp.20711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber KE, Mitani JC, Watts DP, Vigilant L (2013) Male–female socio-spatial relationships and reproduction in wild chimpanzees. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 67(6):861–873. 10.1007/s00265-013-1509-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Fickenscher G, Boesch C (2006) Kin biased investment in wild chimpanzees. Behaviour 143(8):931–955 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LS, Kano F, Stevens JM, DuBois JG, Call J, Krupenye C (2021) Bonobos and chimpanzees preferentially attend to familiar members of the dominant sex. Anim Behav 177:193–206. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2021.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Young LJ (2004) Vasopressin-dependent neural circuits underlying pair bond formation in the monogamous prairie vole. Neuroscience 125(1):35–45. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Hammock EAD, Young LJ (2004a) A method for acetylcholinesterase staining of brain sections previously processed for receptor autoradiography. Biotech Histochem 79(1):11–16. 10.1080/10520290410001671344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Murphy AZ, Young LJ (2004b) Ventral striatopallidal oxytocin and vasopressin V1a receptors in the monogamous prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster). J Comp Neurol 468(4):555–570. 10.1002/cne.10973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Curtis JT, Wang Z (2001) Vasopressin in the lateral septum regulates pair bond formation in male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Behav Neurosci 115(4):910–919. 10.1037/0735-7044.115.4.910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Tribollet E, Dubois-Dauphin M, Pizzolato G, Dreifuss JJ (1989) Localization of oxytocin binding sites in the human brainstem and upper spinal cord: an autoradiographic study. Brain Res 500(1–2):223–230. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90317-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Tribollet E, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ (1991) Localization of high-affinity binding sites for oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain. An Autoradiographic Study Brain Res 555(2):220–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahovetz LM, Young LJ, Hopkins WD (2016) The influence of AVPR1A genotype on individual differences in behaviors during a mirror self-recognition task in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Genes Brain Behav 15(5):445–452. 10.1111/gbb.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kolachana B, Gold B, Olsh A, Nicodemus KK, Mattay V, Dean M, Weinberger DR (2009) Genetic variants in AVPR1A linked to autism predict amygdala activation and personality traits in healthy humans. Mol Psychiatry 14(10):968–975. 10.1038/mp.2008.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Domes G, Kirsch P, Heinrichs M (2011) Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nat Rev Neurosci 12(9):524–538. 10.1038/nrn3044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani JC (2009) Cooperation and competition in chimpanzees: current understanding and future challenges. Evol Anthropol 18(5):215–227. 10.1002/evan.20229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland MM, Navabpour SV, Mareno MC, Schapiro SJ, Young LJ, Hopkins WD (2020) AVPR1A variation is linked to gray matter covariation in the social brain network of chimpanzees. Genes Brain Behav:e12631. 10.1111/gbb.12631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CM, Stanton MA, Lonsdorf EV, Wroblewski EE, Pusey AE (2016) Chimpanzee fathers bias their behaviour towards their offspring. R Soc Open Sci 3(11):160441. 10.1098/rsos.160441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair HP, Young LJ (2006) Vasopressin and pair-bond formation: genes to brain to behavior. Physiology 21:146–152. 10.1152/physiol.00049.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okhovat M, Berrio A, Wallace G, Ophir AG, Phelps S (2015) Sexual fidelity trade-offs promote regulatory variation in the prairie vole brain. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Palombit R (1994) Dynamic pair bonds in Hylobatids: implications regarding monogamous social systems. Behaviour 128(1–2):65–101. 10.1163/156853994X00055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Huang XF, & Toga AW (2000). The rhesus monkey brain in stereotaxic coordinates.

- Preis A, Samuni L, Mielke A, Deschner T, Crockford C, Wittig RM (2018) Urinary oxytocin levels in relation to post-conflict affiliations in wild male chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus). Horm Behav 105:28–40. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prüfer K, Munch K, Hellmann I, Akagi K, Miller JR, Walenz B, Koren S, Sutton G, Kodira C, Winer R, Knight JR, Mullikin JC, Meader SJ, Ponting CP, Lunter G, Higashino S, Hobolth A, Dutheil J, Karakoç E, Alkan C, Sajjadian S, Catacchio CR, Ventura M, Marques-Bonet T, Eichler EE, André C, Atencia R, Mugisha L, Junhold J, Patterson N, Siebauer M, Good JM, Fischer A, Ptak SE, Lachmann M, Symer DE, Mailund T, Schierup MH, Andrés AM, Kelso J, Pääbo S (2012) The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes. Nature:1–5. 10.1038/nature11128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusey A, Murray C, Wallauer W, Wilson M, Wroblewski E, Goodall J (2008) Severe aggression among female Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii at Gombe National Park. Tanzania Int J Primatol 29(4):949. 10.1007/s10764-008-9281-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana DS, Rokicki J, van der Meer D, Alnaes D, Kaufmann T, Cordova-Palomera A, Dieset I, Andreassen OA, Westlye LT (2019) Oxytocin pathway gene networks in the human brain. Nat Commun 10(1):668. 10.1038/s41467-019-08503-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling JK, Young LJ (2014) The biology of mammalian parenting and its effect on offspring social development. Science 345(6198):771–776. 10.1126/science.1252723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CN, Ross AP, Sahu SP, others (2018) Oxytocin-and arginine vasopressin-containing fibers in the cortex of humans, chimpanzees, and rhesus macaques. American Journal of [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Young LJ (2009) Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol 30(4):534–547. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Freeman SM, Spiegel LL, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ (2009) Variation in oxytocin receptor density in the nucleus accumbens has differential effects on affiliative behaviors in monogamous and polygamous voles. J Neurosci 29(5):1312–1318. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5039-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuni L, Preis A, Mundry R, Deschner T, Crockford C, Wittig RM (2017) Oxytocin reactivity during intergroup conflict in wild chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(2):268–273. 10.1073/pnas.1616812114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuni L, Preis A, Deschner T, Crockford C, Wittig RM (2018) Reward of labor coordination and hunting success in wild chimpanzees. Commun Biol 1:138. 10.1038/s42003-018-0142-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorscher-Petcu A, Dupré A, Tribollet E (2009) Distribution of vasopressin and oxytocin binding sites in the brain and upper spinal cord of the common marmoset. Neurosci Lett 461(3):217–222. 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staes N, Stevens JM, Helsen P, Hillyer M, Korody M, Eens M (2014) Oxytocin and vasopressin receptor gene variation as a proximate base for inter- and intraspecific behavioral differences in bonobos and chimpanzees. PLoS ONE 9(11):e113364. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staes N, Guevara EE, Helsen P, Eens M, Stevens JM (2021) The Pan social brain: an evolutionary history of neurochemical receptor genes and their potential impact on sociocognitive differences. J Hum Evol 152:102949. 10.1016/j.jhevol.2021.102949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Hare B, Lehmann H, Call J (2007) Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: the cooperative eye hypothesis. J Hum Evol 52(3):314–320. 10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FB, Lanting F (1997) Bonobo: the forgotten ape. Univ of California Press [Google Scholar]

- Waldherr M, Neumann ID (2007) Centrally released oxytocin mediates mating-induced anxiolysis in male rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(42):16681–16684. 10.1073/pnas.0705860104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walum H, Young LJ (2018) The neural mechanisms and circuitry of the pair bond. Nat Rev Neurosci 19(11):643–654. 10.1038/s41583-018-0072-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ferris CF, De Vries GJ (1994) Role of septal vasopressin innervation in paternal behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91(1):400–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Toloczko D, Young LJ, Moody K, Newman JD, Insel TR (1997) Vasopressin in the forebrain of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus): studies with in situ hybridization, immunocyto-chemistry and receptor autoradiography. Brain Res 768(1–2):147–156. 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00636-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ML, Boesch C, Fruth B, Furuichi T, Gilby IC, Hashimoto C, Hobaiter CL, Hohmann G, Itoh N, Koops K, Lloyd JN, Matsuzawa T, Mitani JC, Mjungu DC, Morgan D, Muller MN, Mundry R, Nakamura M, Pruetz J, Pusey AE, Riedel J, Sanz C, Schel AM, Simmons N, Waller M, Watts DP, White F, Wittig RM, Zuberbühler K, Wrangham RW (2014) Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts. Nature 513(7518):414–417. 10.1038/nature13727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig RM, Crockford C, Deschner T, Langergraber KE, Ziegler TE, Zuberbuhler K (2014) Food sharing is linked to urinary oxytocin levels and bonding in related and unrelated wild chimpanzees. Proc Biol Sci 281(1778):20133096. 10.1098/rspb.2013.3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ (1999) Oxytocin and vasopressin receptors and species-typical social behaviors. Horm Behav 36:212–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ (2015) Oxytocin, social cognition and psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacology 40(1):243–244. 10.1038/npp.2014.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Wang Z (2004) The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nat Neurosci 7(10):1048–1054. 10.1038/nn1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Toloczko D, Insel TR (1999) Localization of vasopressin (V1a) receptor binding and mRNA in the rhesus monkey brain. J Neuroendocrinol 11(4):291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Lim MM, Gingrich B, Insel TR (2001) Cellular mechanisms of social attachment. Horm Behav 40(2):133–138. 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Zhang Q (2021) On the origins of diversity in social behavior. Japanese Journal of Animal Psychology, 71-1. doi: 10.2502/janip.71.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.