Abstract

Implantable cardiac devices represent the first line treatment option used not only for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death but also for primary prevention in patients with cardiac pathologies considered at risk of sudden cardiac death caused by ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. The number of women with implantable cardiac devices reaching child bearing age is expected to increase more and more in the next years. Despite this tendency, there are only a few reported cases of pregnancies in implantable cardiac defibrillator carriers, leading to insufficient evidence and clear guideline recommendations on how to manage and monitor pregnancy in patients with this type of cardiac pathology. Closely monitoring within a multidisciplinary team consisting of an obstretician, electrophysiologist and anesthesiologist is required for this group of pregnant patients in order to achieve the best maternal and neonatal results.

The present study describes the case of succesful outcome in a 27-year-old implantable cardiac defibrillator carrier implanted after an aborted cardiac arrest and reccurent polymorphic ventricular tachycardia due to myocarditis eight years prior to pregnancy, with an aim to emphasize the monitoring particularities and management during pregnancy.

Keywords:implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), pregnancy, myocarditis.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of performed implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and pacemakers has increased in the last years, including a growing population of women of reproductive age (1). While most ICDs are implanted for secondary prevention, in younger patients the indications for ICDs are usually for primary prevention (congenital heart diseases, inherited cardiomyopathies or channelopathies) (2). Another indication for ICD implantation for either primary or secondary prevention is represented by post-myocarditis cardiomyopathy. Myocarditis represents a form of heart muscle disease with mostly unknown aetiology. The physiopathology of myocarditis could be related to infections (viruses, bacteria, fungi), immune-mediated mechanisms (allergens, toxins, alloantigens) or toxic agents (drugs, heavy metals, hormones) (3). Although the true incidence is not known, the reported estimated global prevalence of myocarditis was 22 of 100,000 patients/year (2). The prevalence of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias after myocarditis is elevated and it is constant over time (4). Pregnancy itself presents a higher risk for arrhythmogenic events due to the physiologic modifications such as increased cardiac output, pregnancy hormones and increased sympathetic stimulation (1, 3). Despite the fact that this population of patients is constantly growing, there are few to almost no recommendations regarding the adequate management of pregnancy and delivery in these cases. At present, the Romanian Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (SOGR) does not have a clinical guideline regarding cardiomyopathy management in pregnancy.

CASE PRESENTATION

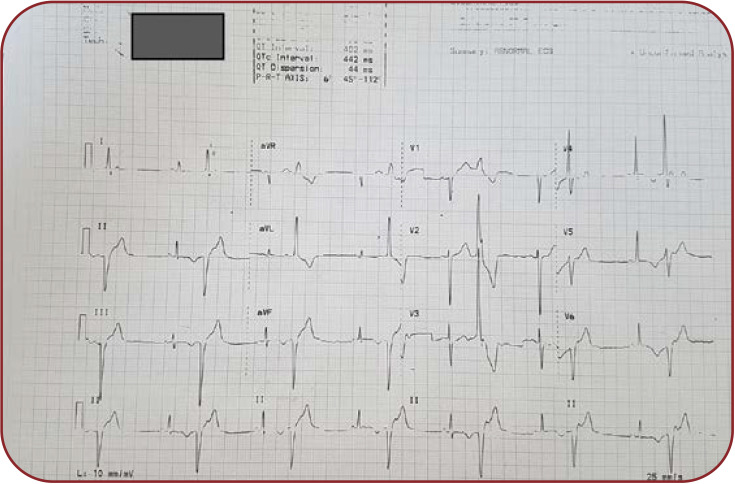

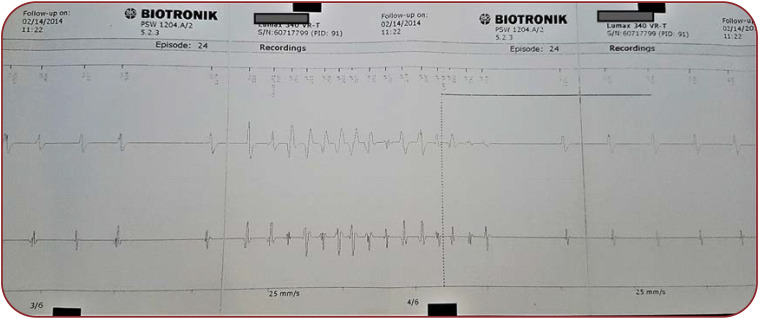

We describe the case of a 27-year-old nullipara primigesta pregnant patient who presented to our medical unit for pregnancy monitoring at 13 weeks of amenorrhea with a singleton pregnancy that was obtained spontaneously. The patient’s medical history includes mitral valve prolapse, mild mitral insufficiency and extrasystolic arrhythmia (ventricular bigeminism) (Figure 1) diagnosed in 2008 after two episodes of syncope and post-myocarditis cardiomyopathy in 2013 with preserved ejection fraction (50%), which lead to the decision to implant an ICD (Figure 2) for secondary prevention after an aborted cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation eight years prior to pregnancy. During this period, the ICD history showed that she had 16 episodes of ventricular fibrillation and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (six times), properly treated by ICD (Figure 3). Extracardiac history was represented by lumbar scoliosis with a Cobbs angle of 45 degrees. Her medication prior pregnancy consisted of low dose beta-blocker (50 mg metoprolol succinate) daily.

During pregnancy, the patient’s interdisciplinary monitoring consisted of cardiac evaluation by the cardiologist every three months. There were no signs of congestion. The ICD history revealed five episodes of unsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and two episodes of sustained ventricular tachycardia at 10 and 28 weeks of gestation, respectively, both being supressed by antitachycardia pacing function of the ICD. No shock was delivered by the ICD during pregnancy. An echocardiography performed at 37 weeks of gestation excluded the dilation of the left cardiac cavities, showing that the left ventricle ejection fraction remained stable at a value of 50%. The right cavities had normal sizes and function. There was no worsening in the grade of mitral regurgitation and tricuspid regurgitation. Given the favourable course of the pregnancy, the administered treatment did not need any modifications.

The pregnancy evolution was uneventful, no anatomical anomaly was detected at ultrasound evaluations, the foetal growth and amniotic fluid index during pregnancy and all measurements remained within the standard charts. The patient had a genital infection with Ureaplasma urealyticum at the beginning of the pregnancy, which was treated successfully. Doppler ultrasound examination of the uterine arteries showed a constant decrease in blood flow every second beat, secondary to the ventricular bigeminism (Figure 4).

Considering the vast cardiologic pathology, the patient was referred to elective C-section at 37 weeks and four days of gestation due to spontaneously rupture of membranes, under direct supervision of the electrophysiology specialist in the operating room, with continuous electrocardiography monitoring, with indication to turn off the ICD function during surgery. During delivery, the patient was under total anaesthesia with no incidents occurring. After spending a day in the ICU unit, the patient returned to the obstetric ward with normal blood pressure, normal hearth rate in sinus rhythm, no fever and normal diuresis. A 3050 g female newborn with an Apgar score of 10 at one minute was delivered by caesarean section, with a normal adaptation to the extrauterine life without cardiac or respiratory disturbances and no cardiac anatomical anomalies detected after birth.

DISCUSSION

Is ICD and pregnancy a good combination? Most of the cardiac diseases requiring an ICD bear an increased risk of sudden death by a heart rhythm disorder (2). We believe that carrying an ICD is not a contraindication for pregnancy. Our patient and most likely many ICD-carrying patients would not have even reached the fertile age without the help of ICDs, as studies revealed a 10-year survival rate of only 45% (mostly due to sudden cardiac death) (3).

The collaboration between the electrophysiologist and obstetrician is mandatory in these cases. The patient must be carefully evaluated and ICD interrogation must be performed more frequently than the standard protocol in non-pregnant patients in order to identify complications or malfunctions promptly. Bouslama et al (2) reported monthly evaluations in an ICD patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In our case, evaluations were established every three months. The patient was educated to address the clinic for every health status modification. Interdisciplinary collaboration is always beneficial; the team has to establish the proper moment and the best way of delivery. They have to prepare the surgery event by assuring all the potential needs for any cardiac event that could occur during the time when the fetus is still dependent of the maternal cardiovascular system. The patient has to be ensured with an appropriate cardiac monitoring throughout the entire surgery.

Shock treatment during pregnancy is still a debated topic as no clear evidence for foetal harm is available. The European Society of Cardiology recommends implantation of ICD preferably before conception in patients at high risk for sudden cardiac death (5). Boule et al (1) reported that, during their study, two patients received defibrillation shocks: one of them received nine shocks with no further harm to the foetus, while the second patient received two shocks at four weeks of gestation resulting in miscarriage one week later (1). Fortunately, that was not the case for our patient, as she did not need defibrillation shocks during pregnancy.

Carrying an ICD brings a risk of device related complications (lead related). Kluman et al (5) reported lead related complications in 20% of ICD implantations during a follow up period of 10 years, more often in young patients and females. Possible complications include lead thrombosis, lead fracture or lead failure. The incidence of these complications is difficultl to be estimated in pregnant women who are also ICD carriers. A systematic review by Topf et al (6) identifies four studies with limited number of cases (maximum 44 cases), with a single case of lead intracardiac thrombosis in a woman with family history of thrombotic events, more specifically homozygous polymorphism for factor V. Due to complex cardiac pathology, we decided to perform a thrombophilia screening for our patient, with negative result. During pregnancy, there was no complication related to the intracardiac device.

Although cardiac pathology represents approximatively 1% of all complications during pregnancy, most of the cardiac pathology can have a high risk of complications for the mother and foetus, from arrythmia that leads to sudden death, tissue necrosis or maternal hypotension which can alter the placental perfusion with subsequent acute foetal suffering (3). ROPAC registry (7) reports an incidence of ventricular arrhythmia of 1.4% in pregnant women with cardiovascular diseases. The risk depends on the pregnancy trimester (higher in the third one) and NYHA class before conception. As for the medication, current guidelines recommend continuing treatment with beta-1 selective beta-blockers (4). Generally, beta-blockers are considered safe during pregnancy. A large cohort of pregnancies exposed to beta-blockers including metoprolol, during the first trimester found no association between this class of medication and congenital malformations (8). A retrospective study by Duas et al (9) on a population of 4847 pregnancy exposed to metoprolol confirms no existing associations between exposure to beta-blockers and foetal cardiac malformation. As for the intrauterine growth restriction, the same cohort showed that exposure to metoprolol is not significantly higher than the control group (10).

Which is better, C-section or vaginal birth? The decision on how to deliver should always be personalized, considering the severity of the underlying heart disease and the arrhythmogenic risk, as there are no precise indications in the current guidelines. The European Society of Cardiology recommends vaginal delivery for most of the stable, low and moderate risk cardiomyopathies such as dilated of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but with no recommendations on patients with ICD implants and recurrent ventricular tachycardia (4). Thus, considering the high amount of stress and emotions involved during a vaginal birth as well as the periods of intense muscular contraction, which naturally pushes the heart to a higher effort that can decompensate a cardiac arrythmia, we consider C-section birth, with general or spinal anaesthesia, a more viable option, as it allows to a more predictable and controllable environment in which the birth can take place. The peripartum management is the same as for every surgery in a patient with intracardiac device. For ICDs, it includes interrogation of the device, turning of the antitachycardia and shock therapy preferably with a programming machine, placing transthoracic defibrillation pads as well as continuous electrocardiographic monitoring (11). All this protocol was followed in our case, with the participation of the electrophysiologist in the operating room.

CONCLUSION

An ICD carrying pregnant woman represents an enormous challenge for every practitioner and its management must be the result of a flawless collaboration between obstetrician, cardiologist, and intensive care unit doctor.

Obstetrical and cardiological societies around the world must work together to provide the framework for future guidelines regarding the management of all cardiovascular pathologies associated with pregnancies. As technology advances more and more, providing earlier detection and conservative treatment of these illnesses, the number of women with cardiac pathology reaching fertile age and obtaining pregnancies will only increase in time.

Conflict of interests: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

FIGURE 1.

Electrocardiogram revealing 12 derivations with ventricular bigeminism

FIGURE 2.

Chest X-ray, posteroanterior incidence, ICD unicameral, moderate scoliosis

FIGURE 3.

Electrocardiographic intracardiac aspect of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia spontaneously stopped during charging of cancelled internal electric shock

FIGURE 4.

Doppler ultrasound evaluation of the right uterine artery, aspect due to ventricular bigeminism at 13 weeks and two days of pregnancy

Contributor Information

Oana MUSCALU, Department of Cardiology, Colentina Clinical Hostpital, Bucharest, Romania.

Dragos TUDORACHE, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Elias University Emergency Hospital, Bucharest, Romania.

Bianca-Margareta MIHAI, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Filantropia Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania.

Ioana Teodora VLADAREANU, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, Bucharest, Romania.

Roxana Elena BOHILTEA, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bucharest, Romania.

References

- 1.Boulé S, Ovart L, Marquié C, et al. Pregnancy in women with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: is it safe? Europace. 2014;16:1587–1594. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouslama MA, Ferhi F, Hacheni F, et al. Pregnancy and delivery in woman with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: what we should know. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:236. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.236.9995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelargonio G, Pinnacchio G, Narducci ML, et al. Long-Term Arrhythmic Risk Assessment in Biopsy-Proven Myocarditis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165–3241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleemann T, Becker T, Doenges K, et al. Annual rate of transvenous defibrillation lead defects in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators over a period of >10 years. Circulation. 2007;115:2474–2480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.663807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topf A, Bacher N, Kopp K, et al. Management of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators during Pregnancy-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1675. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ertekin E, van Hagen IM, Salam AM, et al. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia during pregnancy in women with heart disease: Data from the ROPAC, a registry from the European Society of Cardiology. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan L, Ng A, Chen W, et al. β-Blocker Exposure in Pregnancy and Risk of Fetal Cardiac Anomalies. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:885–887. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateman BT, Heide-Jørgensen U, Einarsdóttir K, et al. β-Blocker Use in Pregnancy and the Risk for Congenital Malformations: An International Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:665–673. doi: 10.7326/M18-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan L, Ng A, Chen W, et al. Beta-blocker subtypes and risk of low birth weight in newborns. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2018;20:1603–1609. doi: 10.1111/jch.13397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone ME, Salter B, Fischer A. Perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107 Suppl 1:116–126. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]